Abstract

Objective:

To review the experience of a large-volume trauma center in managing and treating casualties of suicide bombing attacks.

Summary Background Data:

The threat of suicide bombing attacks has escalated worldwide. The ability of the suicide bomber to deliver a relatively large explosive load accompanied by heavy shrapnel to the proximity of his or her victims has caused devastating effects.

Methods:

The authors reviewed and analyzed the experience obtained in treating victims of suicide bombings at the level I trauma center of the Hadassah University Hospital in Jerusalem, Israel from 2000 to 2003.

Results:

Evacuation is usually rapid due to the urban setting of these attacks. Numerous casualties are brought into the emergency department over a short period. The setting in which the device is detonated has implications on the type of injuries sustained by survivors. The injuries sustained by victims of suicide bombing attacks in semi-confined spaces are characterized by the degree and extent of widespread tissue damage and include multiple penetrating wounds of varying severity and location, blast injury, and burns.

Conclusions:

The approach to victims of suicide bombings is based on the guidelines for trauma management. Attention is given to the moderately injured, as these patients may harbor immediate life-threatening injuries. The concept of damage control can be modified to include rapid packing of multiple soft-tissue entry sites. Optimal utilization of manpower and resources is achieved by recruiting all available personnel, adopting a predetermined plan, and a centrally coordinated approach. Suicide bombing attacks seriously challenge the most experienced medical facilities.

Following a suicide bombing attack, numerous casualties with multiple penetrating wounds and blast injury are brought to the emergency department. Attention is directed at evaluating the degree of injury produced by each missile and to the care of seemingly moderate casualties. Implementation of a predetermined plan and a centrally coordinated effort are essential to achieve optimal utilization of manpower and resources.

The number and extent of worldwide suicide attacks has risen sharply in recent years.1–3 Popularized by militant Islamic organizations to terrorize buses in Israel, the utilization of suicide bombers has been adopted by other groups. Suicide bombing attacks illustrate the ability of suicide attackers to mingle within a crowd and detonate an explosive device in the vicinity of their victims. The injuries sustained by survivors of these well-planned attacks combine the lethal effects of penetrating trauma, blast injury, and burns.4–10

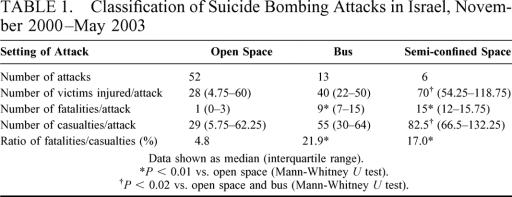

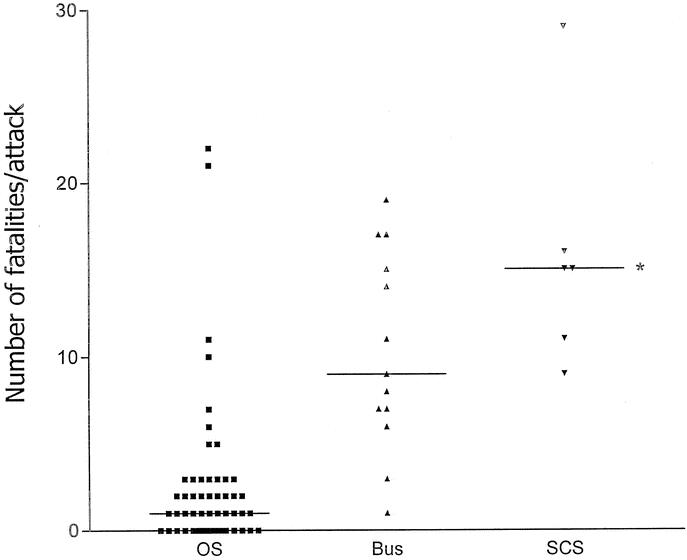

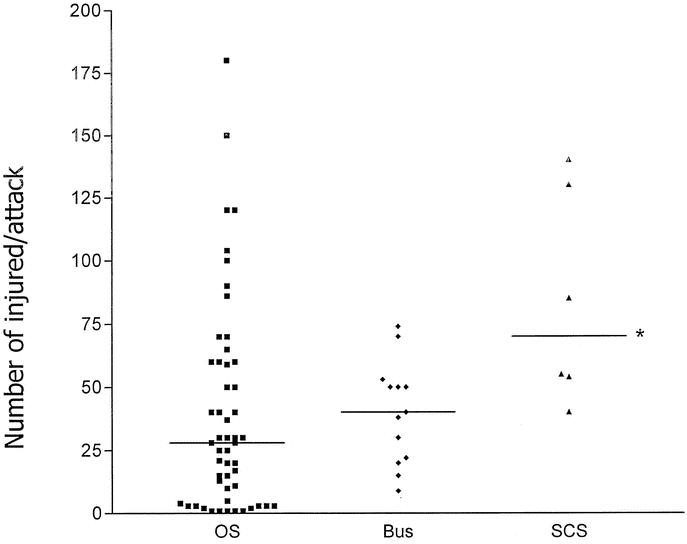

Between November 2000 and May 2003, 71 suicide bombing attacks were carried out in Israel. Three settings were predominantly targeted: (A) open spaces (OS), such as pedestrian malls, open markets, and bus stops; (B) buses; and (C) semi-confined spaces (SCS), such as restaurants and cafés (Table 1). Attacks in OS usually involve 1 or 2 attackers. The energy of the blast dissipates inversely with the distance to the second power, and injury is limited to victims in close proximity to the explosive device. The effects of blast injury when a bomb is detonated inside a confined space such as a bus have been described previously.6 Victims usually sustain severe primary blast lung injury (BLI) and the fatality/casualty ratio is high (Table 1).8 Attacks inside semi-confined, crowded spaces are characterized by the large number of casualties and fatalities, and by the severity and scope of penetrating injuries (Figs. 1 and 2). We describe the attack on the Sbarro pizzeria, which is representative of such attacks. The unique circumstances associated with suicide bombing attacks are discussed and our experience with the management of victims is analyzed.

TABLE 1. Classification of Suicide Bombing Attacks in Israel, November 2000–May 2003

FIGURE 1. The number of fatalities per suicide bombing attack according to the different setting. OS, open space; SCS, semi-confined space. *P = 0.0003 versus OS (Mann-Whitney U test).

FIGURE 2. The number of victims injured per suicide bombing attack according to the different setting. OS: open space; SCS: semi-confined space. *P < 0.02 versus OS and bus (Mann-Whitney U test).

THE SBARRO ATTACK

On August 9, 2001 just before 2 pm, a suicide bomber detonated an explosive device inside a crowded Sbarro pizza restaurant in Jerusalem. The device contained 8–10 kg of high-grade explosive material accompanied by a large amount of ball bearings, bolts, and nuts (Fig. 3). The suicide bombing attack in the Sbarro restaurant generated 146 casualties, of which 14 were immediate deaths.

FIGURE 3. An “ordinary household” nut removed from the thigh of a 19-year-old female.

The Protocol

The only chance for victims who develop severe respiratory distress or severe hemorrhagic shock in the field is the availability of early advanced life support. Emergency medical services (EMS) crews are therefore instructed to follow the scoop-and-run approach in these circumstances. Needle thoracostomy and tracheal intubation are the only procedures performed in the field. Victims with amputated body parts who are not showing signs of movement and those who are pulseless with dilated pupils are considered dead. No further efforts are spent on these victims and attention is directed to evacuating the remaining victims.

There are 4 emergency departments (ED) in Jerusalem, and the Ein Kerem Campus ED is located furthest from the Sbarro restaurant (9.5 km, 6 mi). Regardless of the distance, EMS crews are instructed to evacuate the most severely injured victims to the Ein Kerem Campus, the only level I trauma center in Jerusalem, with more experience in recognizing and treating complex injuries. The Ein Kerem ED is divided into a designated trauma room and a general admitting area. The trauma room is equipped with respirators, monitoring devices, built-in plain film arms, and portable sonograms and has the capacity to treat 4 severely injured patients simultaneously. Surgeons have the capability to perform surgical procedures ranging from venous cut-down to ED thoracotomy.

The initial EMS report described scores of casualties with an unknown number of fatalities inside a crowded restaurant. A detailed protocol, specifically designed for such circumstances, was initiated. All patients in the ED were transferred to the floors and all nonurgent activity was halted. Elective diagnostic procedures such as plain film, sonogram, computed tomography (CT), and angiogram were deferred. Operating room (OR) administration was alerted and 7 procedures scheduled for that afternoon were postponed. Operations in process were allowed to proceed unaltered. Available OR personnel prepared an additional OR, which is dedicated to trauma patients.

The attack occurred when the majority of personnel were available almost immediately. In other circumstances, physicians, nurses, and OR personnel are contacted, irrespective of call schedules, by telephone via a structured list. In most instances this was unnecessary as hospital personnel were already alerted of the attack either by relatives or friends, the media, the internet, or by simply hearing the blast. Surgical personnel arrived at the ED and were organized into predetermined teams. General surgery teams and subspecialty teams were led by an attending physician and included 2 surgical residents. Each team was assigned to 1 bed in the trauma room or 3–4 beds in the admitting area. An anesthesiologist was integrated into the general surgery teams assigned to the trauma room.

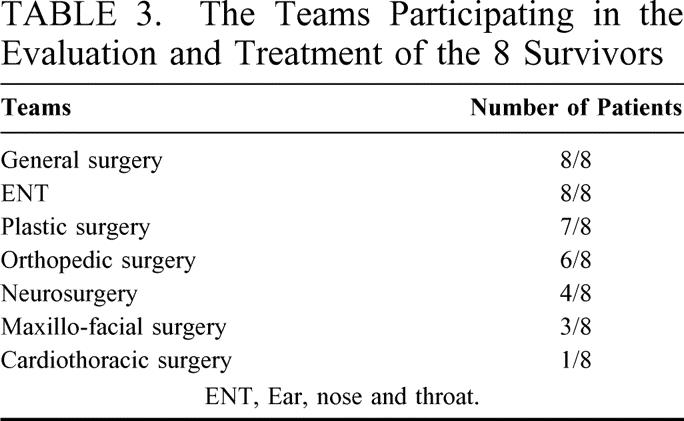

The most experienced trauma surgeon available was designated as surgeon-in-charge (SIC). The SIC received incoming EMS crews and triaged the victims into either the trauma room or the admitting area according to the presence of immediate life-threatening injuries. The SIC accompanied the most severely injured victims into the trauma room and orally communicated his findings to the treating teams. The SIC determined OR priority and did not participate in surgical procedures in the preliminary phases of triage and evaluation. Teams of general surgeons examined all the patients initially. These teams determined the need for further examination by subspecialty teams such as orthopedics, plastic surgery, and neurosurgery. Due to the high incidence of tympanic membrane trauma following blast injury, all patients were examined by teams from ear, nose, and throat (ENT).11

During the initial 6–8 hours, the SIC conducted repeated reassessments on all patients. These bedside reassessments were conducted following initial evaluation by the designated teams and consisted of repeated physical examination and review of the laboratory and imaging findings. Prioritization of treatment was determined by the SIC according to the presence and severity of life and limb-threatening injuries, the degree of respiratory compromise, and the availability of operating rooms.

The Injuries

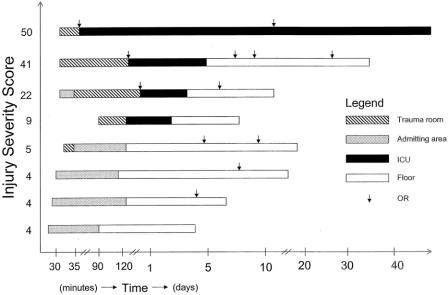

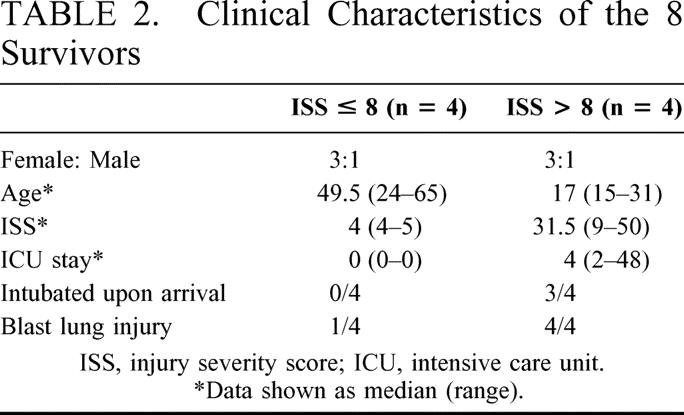

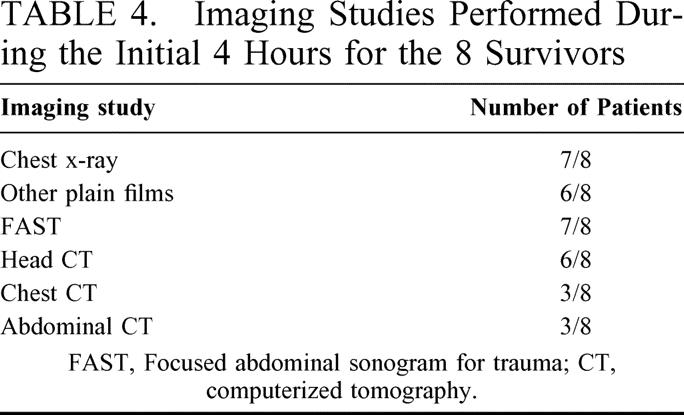

Within 6 minutes 18 patients were brought to the ED. Four patients were brought to the trauma room and 14 patients were directed to the admitting area. A 17-year-old male with severe brain injury was pulseless and underwent ED thoracotomy. Resuscitative efforts failed, he was pronounced dead, and transferred to the admitting area. Following initial evaluation, 1 patient with an injury severity score (ISS) of 22 was transferred from the admitting area to the trauma room and 1 patient from the trauma room with an ISS of 5 was transferred to the admitting area (Fig. 4). Fifty-seven minutes later a fifth patient with head injury was transferred to the trauma room from another hospital. Ten patients with minor injuries were discharged from the ED and were excluded from the analysis. The condition of the 8 survivors, the teams that participated in their evaluation and treatment, and the initial diagnostic work up are shown in Tables 2, 3 and 4. The pattern of injuries sustained by the 3 patients who were taken to the OR within the initial 4 hours is shown in Table 5.

FIGURE 4. Timing of arrival, location, surgical procedures, and discharge for the 8 survivors.

TABLE 2. Clinical Characteristics of the 8 Survivors

TABLE 3. The Teams Participating in the Evaluation and Treatment of the 8 Survivors

TABLE 4. Imaging Studies Performed During the Initial 4 Hours for the 8 Survivors

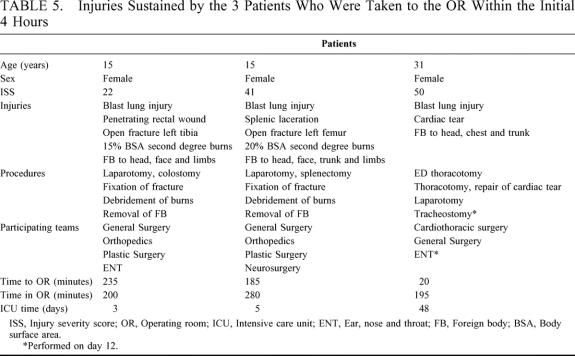

TABLE 5. Injuries Sustained by the 3 Patients Who Were Taken to the OR Within the Initial 4 Hours

ANALYSIS

The Circumstances

There are several factors to consider in understanding the bodily damage caused by the recent wave of suicide bombing attacks in Israel: (A) the high-grade explosive material used by the attackers; (B) the ability of the attackers to detonate the explosive device in proximity to the victims by concealing the explosive device and mingling within a crowd; (C) the ability of the attacker to precisely time the explosion at his or her discretion; and (D) the large load of heavy shrapnel that accompany the explosive material. All the above factors are combined by the attackers to increase the number of casualties and the severity of their injuries. The injuries sustained by the victim depend on the proximity of the victim to the explosive device, the angle at which the victim stands in relation to the center of the explosion, and the height of the explosive device in relation to the victim.

The circumstances associated with these attacks also influence management and decision-making. The uncertainty as to the arrival of additional victims, the mayhem associated with the arrival of anxious family members, the florid scenes associated with these injuries, the often young age of the victims, the possibility that family members of hospital personnel are among the victims, and the risk of second-hit explosions, intensify the chaotic atmosphere that already exists in the ED. These factors underline the importance of forming a plan at the hospital level designed to deal with these circumstances.

Hospital Response

The demand on hospitals dealing with trauma victims varies according to the number of casualties and the severity of their injuries. Everyday resources are used in delivering treatment to one seriously injured patient. Conversely, in a scenario of mass casualties, medical resources are overwhelmed. It has been recently proposed that the circumstances associated with terrorist attacks, ie, the massive influx of casualties over a short time-span, inhibit the ability of medical crews to deliver efficient treatment to all the victims.12 This view is based on mass casualty scenarios in which large numbers of casualties overwhelmed existing medical resources.13 Thus, in dealing with mass casualty scenarios such as the bombing of the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City in 1995, a selective approach is encouraged: one in which overtriage is discouraged; the treatment of moderately injured patients is prioritized over severely injured patients; and imaging studies are restricted or avoided. This approach seems justified in mass casualty scenarios. The Israeli experience with treating victims of suicide bombing attacks likely represents an intermediate situation, one in which the number of casualties is limited by the capacity of the target, ie, bus or restaurant. In these circumstances, ordinary hospital resources are heavily burdened, yet delivery of efficient medical treatment is possible by recruitment of all available personnel and resources.

It is difficult to predict the number of casualties based on the setting and on initial EMS reports. The number of casualties generated by attacks in OS depends on the density of victims at the scene, the number of attackers, and the explosive load. Premature detonation of devices in isolated OS, such as occurred when security personnel confronted the attackers, results in fewer casualties. In these situations EMS reports are reliable and the number of casualties is predictable. When these attacks involve crowded OS, SCS, and buses, initial EMS reports are confused and often contradictory. We have therefore adopted a universal response to attacks in crowded places. Evacuation of the ER, a halt to scheduled OR activity, and mobilization of personnel is routinely performed. Partial normalization of activity may follow confirmation of the magnitude of the attack.

Triage

After an attack, many victims are brought to the admitting area over a period of minutes either by qualified prehospital personnel or many times by by-standers. Triage is of utmost importance in these scenarios.14–15 A trauma-qualified, general surgeon is designated as SIC and waits at the ambulance unloading point to perform triage. The attack on the Sbarro restaurant occurred at 2 pm and this was therefore possible. In other circumstances, the most experienced trauma surgeon available is designated as SIC. Attention is focused on signs of severe respiratory distress and hemodynamic instability. Evaluation and treatment of the severely injured is initiated in a trauma room setting. The short evacuation times secondary to the proximity of suicide attacks to the urban setting and the usually young age of the victims favor an aggressive approach in the majority of cases.16 In retrospect, of the 2 patients without signs of life who underwent ED thoracotomy, 1 had severe brain injury and was obviously unsalvageable. The second patient had penetrating cardiac injury and was potentially salvageable,17 but developed hypoxic brain damage secondary to prolonged hypotension. Terminating resuscitative efforts in these chaotic circumstances where little is known regarding prehospital status is extremely difficult. Nonetheless, performing these procedures on unsalvageable victims such as those without any signs of life or those with severe brain injury, may compromise delivery of efficient care to salvageable victims.

Initial Evaluation

We consider undertriage unavoidable in these chaotic situations, and the importance of repeated surveys cannot be over-emphasized. Attention is initially given to identifying patients with signs of BLI such as shortness of breath, tachycardia, and confusion, and those with multiple entry sites and extensive tissue damage, which are markers of more severe trauma. These patients require immediate transfer to a higher-level care environment or to the OR. This is illustrated by the course of events of an 18-year-old male who was injured in the attack on the number 32 bus in Jerusalem, on June 18, 2002. He was diagnosed with burns, and triaged to the admitting area. Within minutes he developed acute respiratory distress caused by BLI. He was immediately transferred to the trauma room where he was ventilated and bilateral chest drains were inserted.

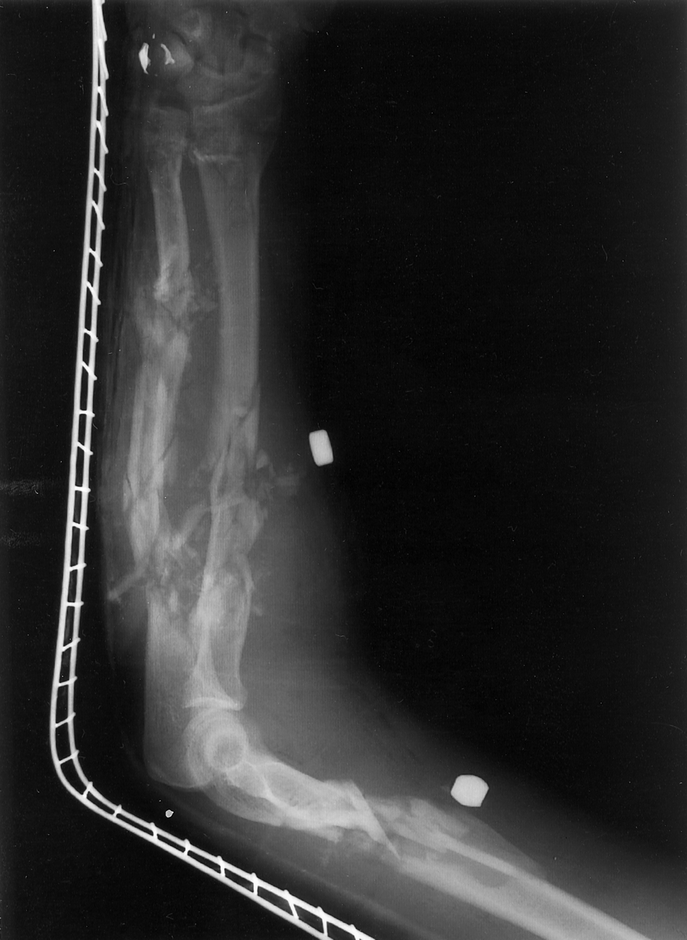

The majority of victims of penetrating trauma sustain injuries to isolated parts of the body such as the head, chest, abdomen, or limbs. Blunt trauma is more commonly a multisite injury, the severity of which depends on the mechanism of injury. The injuries sustained by victims of suicide bombing attacks share the worst of both worlds. The multitude of heavy particles causes damage to a large surface area of the victim, much like blunt trauma. Each particle causes extensive tissue damage at the site of entry, much like penetrating trauma (Figs. 5 and 6). Survivors typically suffer a combination of wounds of varying severity and location, and the diagnostic work up is focused on determining the extent of damage caused by each missile.

FIGURE 5. Lateral film of the left arm of 25-year-old male showing compound fractures of the humerus, radius, and ulna caused by foreign bodies.

FIGURE 6. A 16-year-old female who was standing with her back towards the attacker. She sustained penetrating rectal injury.

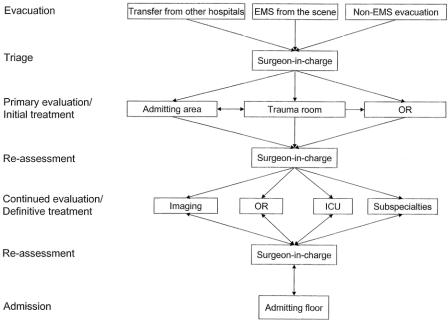

Control

Control and coordination are achieved by the “accordion” approach. According to this approach, patient evaluation and management proceed through repeated cycles consisting of a dispersal phase and a convergence phase (Fig. 7). Activity is coordinated and controlled by the SIC who is aware of the overall situation and has the oversight to prioritize evaluation and treatment. Chaos is gradually managed once the number of patients requiring further work up is reduced. Patients undergoing surgery, often simultaneously by different teams, are reassessed by the SIC in the OR with the treating teams. The overall condition of the patient, the sequence of therapy, the need for further imaging studies, and the need for intensive care unit (ICU) admission are discussed and finalized.

FIGURE 7. The “accordion” approach. Control and prioritization are achieved by a centrally coordinated effort centered on the surgeon-in-charge.

In analyzing this approach we must consider the following: (A) many hours and sometimes days are required for the situation to stabilize and eventually normalize (Fig. 4); (B) treating teams are physically and emotionally exhausted from the continuous workload, especially when repeat attacks occur within days; and (C) repeated reassessment by the treating teams and SIC to ascertain that all patients receive optimal care is fundamental. In these circumstances, a strong personal commitment by the treating teams and SIC is pivotal to success. Depending on the magnitude of the attack, this commitment may last from several hours to several days. During this period, other professional and personal commitments are sacrificed.

Treatment

The basic rules of trauma, the ABC, and the concepts of trauma management such as the abbreviated laparotomy and damage control, are applied universally.18–22 Their application may be modified in different situations. As in all trauma cases, airway control and acute breathing problems are prioritized. Hypotensive victims of penetrating abdominal or thoracic trauma are taken to the operating room to perform laparotomy and/or thoracotomy. This approach stems from our understanding that the mechanism of hypotension is major intra-abdominal and/or intrathoracic bleeding.

Hypotensive victims of suicide bombing attacks with abdominal and/or thoracic injuries believed to contribute significantly to their instability are also taken to the OR. The approach in the OR to victims of suicide attacks may be slightly modified in these cases. Multiple shrapnel entry sites are common in survivors and it is impossible to determine which of the numerous entry sites is the cause of hypotension (Fig. 6). The degree of soft-tissue damage associated with these injuries is also difficult to quantitate. Since the attackers usually approach the victims from behind, the majority of entry sites are located on the backsides. Positioning the patient in the supine position and performing routine abbreviated laparotomy may actually postpone treatment of these potentially more serious injuries. We propose a modification to the concept of damage control in these cases. Up to 10 to 15 entry sites, ranging in size from 2 to 6 cm in diameter and up to 5–8 cm deep, are packed by 2 to 3 teams in a swift manner with the patient in the left or right lateral decubitus positions. Rapid hemostasis should be achieved within 2–3 minutes. Hypothermia, a leading cause of coagulopathy in trauma patients, may also be diminished by covering these wounds.23 The patient is then positioned in the supine position and laparotomy and/or thoracotomy initiated. This modification may attenuate the degree of soft-tissue damage, lessen hypothermia, achieve better overall hemostasis, and improve survival.

Recombinant activated factor VIIa (rFVIIa) has been successfully used to treat bleeding patients with various coagulopathies. When bound to tissue factor, which is exposed at sites of vessel injury, circulating FVIIa is activated. This complex initiates the coagulation cascade on activated platelet surfaces, which adhere to the site of injury, resulting in the formation of a fibrin clot at the site of injury only.24 Animal studies have shown a significant improvement in mean prothrombin time, mean arterial blood pressure, and mean blood loss in hypothermic, coagulopathic pigs after administration of rFVIIa.25 Noncontrolled reports in trauma patients have suggested that administration of rFVIIa results in improvement of prothrombin time and blood requirement.24 We have used rFVIIa in 3 cases. After the Zion Square attack, a 14-year-old girl sustained multiple shrapnel wounds to her lower extremities with extensive soft-tissue damage (Fig. 8). Her injuries included bilateral multiple open fractures of the femur and tibia, and bilateral obstruction of the posterior tibial artery. The fractures were nailed, but because she developed hypothermia and coagulopathy, the vascular injuries were not repaired and she was transferred to the ICU. She continued to bleed profusely from multiple entry sites and received 57 units of red blood cells, 39 units of FFP, 14 units of platelets, and 19 units of cryoprecipitate. Twenty-two hours after admission, she received 100 microgram/kilogram of rFVIIa with an immediate improvement of her INR from 2.11 to 0.64. More importantly, the bleeding stopped and over the following 24 hours she received 1 unit of red blood cells. Since then, we have successfully treated 2 additional penetrating trauma patients with rFVIIa. These are anecdotal reports. However, in light of recent publications and our experience, we encourage the use of rFVIIa in exsanguinating trauma patients as an adjunct to surgical hemostasis, with or without participation in ongoing randomized trials.

FIGURE 8. The left lower limb of a 14-year-old female who sustained multiple shrapnel injuries. Note extensive soft-tissue damage.

Communication With Families

Family members injured in suicide bombing attacks have been brought to different hospitals because of different patterns of injuries and confusion at the scene. Families are unaware of the condition and location of their relatives. A crisis information center staffed by psychologists, social workers, nurses, hospital spokesperson, and police, is set up and efforts are made to identify and locate the victims and to retrieve information regarding their condition. Identification of victims is facilitated by using Polaroid™ and digital photos. The center is accessible by telephone, and the numbers are shown in the media and on the internet.

During the early hours following an attack, the treating teams do not have the opportunity to communicate directly with the families. We have therefore adopted the role of a nurse coordinator to contact the families and inform them of the condition and progress of their loved ones. The nurse has access to the ED, trauma room, OR, and crisis center and is updated by the surgeons. Once the situation stabilizes, the surgeons join the coordinator and update the families.

Aftermath

Debriefings are conducted regularly following partial normalization, usually within 12–18 hours of the attack. The SIC, department chairmen, treating teams, nurses, nurse coordinators, hospital administration, hospital spokesperson, and EMS representatives participate in the discussion. The event is reviewed and analyzed beginning with the correlation between initial EMS reports and the number and condition of casualties, the number and makeup of teams participating in the event, the number of patients requiring surgery and timing of their surgery, the requirement for additional ICU beds, and the need to cancel nonurgent procedures. Some of the recommendations that we have implemented include: recruitment of personnel via telephone lines and not pagers or cellular phones that crash due to overload, placement of a portable sonogram in the trauma room, transformation of recovery room beds into temporary ICU beds, regulation of physicians’ leave, and creation of the roles of SIC and nurse coordinator.

The days following such attacks are not normal. After the attack on the Sbarro restaurant and as a result of the overload on the ICU, 2 major surgical procedures scheduled for the next morning were postponed. The Israeli Center for Organ Donation was alerted and organ donations were transferred to other centers. Other factors such as physical and emotional burden are more difficult to quantify. Physicians and hospital administration are aware of the difficulties, and nonurgent activity is reduced for several days.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, the approach to victims of suicide bombing attacks leans on the guidelines for trauma victims in general. Specific considerations include the large number of victims, the combined effects of penetrating trauma, blast injury and burns, and the numerous penetrating wounds sustained by each victim. Attention is given to the moderately injured, as these seemingly stable patients may harbor immediate life-threatening injuries. Repeated reassessments can prevent late diagnosis of potentially life and limb-threatening injuries. Modifications to the damage control concept in the severely injured hemodynamically unstable patient may include packing of multiple entry sites prior to abbreviated laparotomy. A predetermined plan and a coordinated approach, centered on the SIC, are essential to optimize utilization of manpower and resources. Hospital personnel and resources are heavily burdened in these circumstances.

Footnotes

Reprints: Gidon Almogy MD, Department of Surgery, University of Southern California, 1510 San Pablo Street, HCC-514, Los Angeles, CA, 90033-4612. E-mail: galmogy@surgery.usc.edu; galmogy@hotmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eiseman B. Combat casualty management for tomorrow's battlefield: urban terrorism. J Trauma. 2001;51:821–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karmy-Jones R, Kissinger D, Golocovsky M, et al. Bomb-related injuries. Mil Med. 1994;159:536–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slater MS, Trunkey DD. Terrorism in America: an evolving threat. Arch Surg. 1997;132:1059–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Philips YY. Primary blast injuries. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15:1446–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wightman JM, Gladish SL. Explosions and blast injuries. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37:664–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leibovici D, Gofrit ON, Stein M, et al. Blast injuries in a bus versus open air bombings: a comparative study of injuries in survivors of open air versus confined space explosions. J Trauma. 1996;41:1030–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper GJ, Maynard RL, Cross NL, et al. Casualties from terrorist bombings. J Trauma. 1983;23:955–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pizov R, Oppenheim-Eden A, Matot I, et al. Blast lung injury from an explosion on a civilian bus. Chest. 1999;115:165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz E, Ofek B, Adler J, et al. Primary blast injury after a bomb explosion in a civilian bus. Ann Surg. 1989;209:484–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Almogy G, Makori A, Zamir O, et al. Rectal penetrating injuries from blast trauma. Isr Med Assoc J. 2002;4:557–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leibovici D, Gofrit ON, Shapira SC. Eardrum perforation in explosion survivors: is it a marker of pulmonary blast injury? Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34:168–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frykberg ER. Medical management of disasters and mass casualties from terrorist bombings: how can we cope? J Trauma. 2002;53:201–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caro D. Major disasters. Lancet. 1974;2:1309–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stein M, Hirshberg A. Medical consequences of terrorism. The conventional weapon threat. Surg Clin North Am. 1999;79:1537–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stein M, Hirshberg A. Limited mass casualties due to conventional weapons-the daily reality of a level I trauma center. In: Shemer J, Shoenfeld Y, eds. Terror and Medicine: Medical Aspects of Biological, Chemical and Radiological Terrorism. Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers; 2003:378–393. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kluger Y. Bomb explosions in acts of terrorism-detonation, wound ballistics, triage and medical concerns. Isr Med Assoc J. 2003;5:235–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rhee PM, Acosta J, Bridgeman A, et al. Survival after emergency department thoracotomy: review of published data from the past 25 years. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190:288–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirshberg A, Walden R. Damage control for abdominal trauma. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77:813–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore EE, Burch JM, Franciose RJ, et al. Staged physiologic restoration and damage control surgery. World J Surg. 1998;22:1184–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mattox KL. Introduction, background, and future projections of damage control surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77:753–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore EE. Staged laparotomy for the hypothermia, acidosis and coagulopathy syndrome. Am J Surg. 1996;172:405–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rotondo MF, Schwab CW, McGonigal MD, et al. “Damage control”: an approach for improved survival in exsanguinating penetrating abdominal injury. J Trauma. 1993;35:375–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jurkovich GJ, Greiser WB, Luterman A, et al. Hypothermia in trauma victims: an ominous predictor of survival. J Trauma. 1987;27:1019–1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinowitz U, Kenet G, Segal E, et al. Recombinant activated factor VII for adjunctive hemorrhage control in trauma. J Trauma. 2001;51:4319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shreiber MA, Holcomb JB, Hedner U, et al. The effect of recombinant factor VIIa on coagulopathic pigs with grade V liver injuries. J Trauma 2002;53:252–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]