Abstract

Background:

Restorative proctocolectomy (RPC) eliminates the risk of colorectal adenocarcinoma in familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) patients, but desmoid tumors, duodenal, and ileal adenomas can still develop. Our aim was to assess the long-term outcome of FAP patients after RPC.

Patients and Methods:

FAP patients who had RPC between 1983 and 1990 were contacted for interview and upper gastrointestinal (GI) and ileal pouch endoscopy.

Results:

Sixty-two males and 48 females had undergone hand-sewn RPC during this period. One patient died postoperatively (0.9%). Among 96 patients available for a minimal follow-up of 11 years, 7 patients died: 3 from causes unrelated to FAP, 2 from metastatic colorectal cancer, and 2 from mesenteric desmoid tumor (MDT). Thirteen patients had a symptomatic MDT (13.5%). Of 73 patients who had an upper GI endoscopy, 52 developed duodenal and/or ampullary adenomas. Four patients required surgical treatment of their duodenal lesions. Among 54 patients who underwent ileal pouch endoscopy, pouch adenomas were noted in 29. No invasive duodenal or ileal pouch carcinoma were detected. Functional results of RPC were significantly worse in MDT patients.

Conclusions:

RPC eliminates the risk of colorectal cancer, and close upper GI surveillance may help prevent duodenal malignancy. MDTs are the principal cause of death, once colorectal cancer has been prevented, and the main reason for worsening functional results.

Among 110 patients with FAP that had restorative proctocolectomy at least 11 years ago, none have developed cancer of the upper gastrointestinal tract or the pouch, but 13 have developed mesenteric desmoid tumors, and 2 have died of these tumors.

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is an autosomal-dominant condition caused by germline mutation of the APC tumor suppressor gene that occurs with a frequency of approximately 1 in 7500 of the general population.1 The defining feature of FAP is the development of multiple adenomatous large bowel polyps in childhood and adolescence that inevitably progress to colorectal carcinoma, so that patients are usually treated by prophylactic colectomy in their teens or early twenties. Controversy exists as to whether proctocolectomy and ileal pouch formation or total colectomy and ileorectostomy (IR) is the best prophylactic operation for FAP patients. Protagonists of colectomy and IR argue that pouch surgery is associated with more frequent and more serious perioperative complications than IR and that the greatest risk of death from cancer lies with upper gastrointestinal tract lesions.2 Protagonists of RPC counter argue that FAP patients are at high risk of rectal cancer, which is at least theoretically eliminated by RPC. Moreover, FAP patients are also predisposed to the development of small bowel polyps, including the ileal reservoir.3 Finally, desmoid tumors, which are poorly understood locally invasive proliferations of myofibroblasts, arise in about 10% of FAP4 patients and may contribute significantly to morbidity and even mortality after either IR or RPC. FAP patients that have had RPC are therefore still at risk to develop adenocarcinoma of the duodenum or/and of the ileal pouch and to develop desmoid tumor. The long-term causes of failure in FAP patients after RPC have not been assessed. Our aim was therefore to assess the long-term complications of RPC for FAP, especially as it relates to failure and causes of death.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

The medical records of all patients with FAP who had undergone RPC, including mucosectomy and hand-sewn anastomosis, between January 1983 and December 1990 were reviewed. Demographic data and data concerning patient's operations and pathologic specimens were obtained. Patients were contacted, interviewed, and recommended to have upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and pouch endoscopy at our institution or at an institution nearer their residence, according to their wishes and the authorization of their regional social security center. Long-term functional data included stool frequency (daytime and nighttime), urgency (inability to retain stool more than 15 minutes), daytime and nighttime continence, need to wear a protective pad, need for medication, perineal skin irritation, and diet. Patients were asked whether they had underwent another surgery elsewhere and the reason for the surgery and whether they had developed desmoid tumors, epidermoid cyst, osteoma, or other tumors.

A side-viewing endoscope was used for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy whereas a flexible sigmoidoscope was used for ileal J-Pouch endoscopy. Polyps seen during endoscopies were biopsied. The number, size, histologic type, and degree of dysplasia of the polyps were recorded. Lesions found in the ileal pouch or in the duodenum or both were staged according to the classification proposed by Spigelman to assess the severity of duodenal polyposis.2 Since 1994, all patients with the diagnosis of FAP are proposed genetic diagnosis. Seventy-five patients of 57 families of this series accepted the test.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables and categorical variables were compared using the Wilcoxon test or the Fisher exact test, respectively.

RESULTS

Patients

Sixty-two males and 48 females underwent RPC for FAP during the study period. The median age at the time of their operation was 26.5 (range, 10–67.5; mean ± SD: 28 ± 11) years. Among the patients tested for APC mutation, a mutation was identified in 50 families (64 patients). Fourteen patients were lost to follow-up. Among the 96 remaining patients, RPC was the initial procedure for 78 patients, 17 had a conversion of an IR to a RPC, and 1 had a conversion of a “straight” ileoanal anastomosis to an RPC with ileal reservoir. The pouch was J-shaped and hand-sewn to the dentate line after complete mucosectomy in all patients. Ten patients had an invasive colon carcinoma: 2 stage I, 7 stage II, and 1 stage III according to the UICC classification.5 One patient also had a stage III rectal cancer, and 14 other patients had an in situ adenocarcinoma. Sixty-seven patients were part of a family known to have FAP, and 29 patients were symptomatic with bleeding (n = 19), diarrhea (n = 6), and abdominal pain (n = 4). The mean follow-up from the time of RPC was 14.6 (±SD 2.0; median, 14; range, 11–18) years.

Mortality

One 18-year-old patient, who had no obvious cardiac history, died 8 hours after operation from unexplained heart failure (0.9%). Two patients found to have colorectal cancer at the time of RPC developed pulmonary and hepatic metastases and died 5 and 30 months following their operation. One patient committed suicide 2 years after RPC from unrelated emotional problems. Two patients died because of a primary lung adenocarcinoma, and 2 other patients died of complications of a desmoid tumor. Thus a total of 7 patients have died since their RPC, 2 from a cancer that developed before their RPC and 2 from desmoid complications relating to FAP that appeared after their RPC.

Long-term Morbidity

Twenty patients required at least 1 other surgical procedure as a result of small bowel obstruction caused by adhesions (n = 3) or mesenteric desmoid (n = 4), pelvic cyst (n = 2), pouch–anal fistulae treated with a seton (n = 2), late pelvic abscess secondary to blind-end J-shaped pouch leakage (n = 1), incisional hernia (n = 1), duodenal adenomas (n = 2), ampullary adenomas (n = 2), villous adenoma of the duodeno–jejunal junction (n = 1), abdominal wall desmoid tumor (n = 2), and mesenteric desmoid tumors (n = 6). Some patients had more than one complication.

One patient who was operated for small bowel obstruction secondary to adhesion in another institution had inadvertent transection of the upper mesenteric artery resulting in necrosis of the distal half of the small bowel, including the ileal reservoir. A permanent ileostomy was required. Six patients developed a total of 6 intercurrent diseases, including Crohn's disease with ulceration of the pouch, thyroid cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, celiac disease, hepatic adenoma, and recurrent renal lithiasis.

Desmoid Tumor

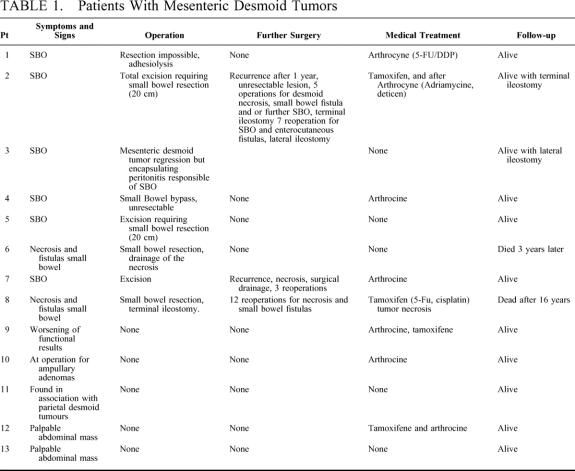

A total of 16 patients developed desmoid tumors, 10 in the mesentery, 3 in the abdominal wall, and 3 in the mesentery and the abdominal wall. Nine patients developed symptomatic mesenteric desmoid tumors (Table 1); 6 resulted in small bowel obstruction, 2 underwent spontaneous necrosis, which led to the formation of small bowel fistula, and 1 was discovered by computed tomography scan as stool frequency was increasing. Four patients had asymptomatic mesenteric desmoid tumors, discovered either intraoperatively at operation for ampullary adenoma (n = 1), in association with abdominal wall desmoid tumor (n = 1) or during abdominal palpation (n = 2), which were confirmed by CT scan.

TABLE 1. Patients With Mesenteric Desmoid Tumors

Upper Gastrointestinal Lesion

Seventy-three patients accepted to undergo upper gastrointestinal surveillance. Among them, 52 patients had developed polyps of the duodenum or the ampulla and were classified according to Spigelman's classification as: stage I, n = 17; stage II, n = 24; stage III, n = 5; and stage IV, n = 2. The 2 patients with stage IV lesions required surgical treatment, with 1 patient undergoing duodenotomy and polypectomy 125 months after RPC and the other needing duodenopancreatectomy 127 months after RPC. Two of the 5 patients with stage III ampullary lesions required reoperation: 1 patient in whom duodenopancreatectomy had been planned was managed by ampullectomy 185 months after RPC because the presence of a mesenteric desmoid tumor made duodenopancreatectomy technically impossible, a second patient had duodenopancreatectomy 193 months after RPC, and a third patient with stage III adenoma of the ampulla was treated by electrocoagulation a year after RPC.

Ileal Pouch Adenomas

Fifty-four patients agreed to have endoscopy of their ileal pouch. Twenty-five patients (47%) had no adenoma. One patient had ulcerations of the pouch mucosa that ultimately proved to be Crohn's disease. Twenty-nine patients (53%) had polyps, all adenomas, 22 grossly visible and 7 microadenomas. No invasive carcinomas were found, 8 patients had stage I lesions, 20 patients had stage II lesions, and 1 patient had a stage IV lesion. The latter patient had previously developed a carcinoma in situ in residual anastomotic glandular mucosa after a previous incomplete mucosectomy, done early in our experience. Resection of this carcinoma had been performed by completion mucosectomy and advancement of the ileal pouch to the dentate line. So far, 42 months later, she has developed ileal pouch adenomas with dysplasia but no recurrent carcinoma. Sulindac resulted in a complete endoscopic response 12 months after initiation of the therapy.

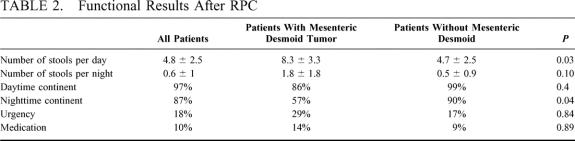

Functional Results

The functional results are detailed in Table 2. The mean ± SD stool frequency per 24 hours was 5.2 ± 2.9 and the mean ± SD night-time stool frequency 0.6 ± 1.1. One episode of pouchitis occurred in 1 patient, which was successfully treated by metronidazole. Patients with mesenteric desmoid tumor had functional results worse than patients without desmoid tumor (Table 2).

TABLE 2. Functional Results After RPC

DISCUSSION

FAP is an inherited disease characterized by the development of hundreds of adenomas in the colon and rectum. Because virtually all patients will develop adenocarcinoma if left untreated, prophylactic colectomy is indicated. Surgical options include restorative proctocolectomy with construction of an ileal reservoir (RPC) and colectomy with ileorectostomy (IR). Total colectomy with IR provides good but not perfect functional results,6 and more importantly, it leaves patients at risk for rectal cancer. Thirty percent of patients after IR develop rectal cancer before the age of 60 years, with an average mortality of about 25%.7 Advocates of IR maintain, however, that rectal cancer is not the primary cause of death of FAP patients.7 They contend that desmoid tumor,8 upper gastrointestinal, and small bowel polyps3 present in FAP patients may also preclude long-term survival. In our series, after a mean follow-up of 14 years after RPC and a minimal follow-up of 11 years, the main cause of death remains colorectal cancers discovered at the time of RPC. None of the patients who had their RPC during the time they had no invasive carcinoma of the colon or rectum have developed a metastatic cancer since their operation, and the main cause of death in these patients was mesenteric desmoid tumor. De Cosse et al9 have reported a cumulative risk of rectal cancer 10 year after IR of 4.5%. Of interest, these authors also reported that 24 patients had a rectal cancer detected less than 6 months after performance of surveillance rectoscopy. Finally, the 5-year cancer survival rate was only 68% and rectal cancer was the primary cause of death in their patients. In a more recent study comparing RPC and IR results,10 2 patients among 21 patients that had had IR, required proctectomy and ileostomy owing to dysplastic changes in rectal polyps. All of these results as well as our own would favor RPC with complete mucosectomy over IR in the prevention of cancer death in FAP patients. Double stapling RPC without mucosectomy leaves in place a segment of the distal part of the rectal mucosa and exposes patients to the risk of developing rectal cancer from residual columnar mucosal cells.11 Four cancers have been reported after RPC, 3 in patients in whom no mucosectomy was performed and a cuff of columnar epithelium was kept in place12–15 and one at the anastomosis suggesting incomplete mucosectomy. Only 1 patient in our series had severe dysplasia. She had previously developed a carcinoma in situ in residual glandular mucosa after incomplete mucosectomy. Resection of this carcinoma had been performed by completion mucosectomy and advancement of the ileal pouch.16 Adenomas with severe dysplasia were seen at endoscopy 42 months later. Sulindac resulted in a complete endoscopic resolution of gross polyps 12 months after initiation.

Moreover, no complication specific to RPC has been observed in our patients, and 4 out the 96 patients followed required a terminal ileostomy, 3 of them because of desmoid mesenteric tumors and another one after inadvertent transection of the superior mesenteric artery during exploration for obstruction of the small intestine. The long term morbidity was dominated by small bowel obstruction that required surgery in 7 patients (7.3%), a risk of small bowel obstruction requiring surgery comparable to the one reported after IR.10 The functional results did not change with time, our results after a median follow-up of 14 years approaching the ones observed after a shorter follow-up.10,17

FAP patients are also at risk for developing duodenal cancer after either RPC or IR. The most common endoscopic feature of the duodenum is multiple small sessile polyps in the descending portion, but some patients develop larger adenomatous polyps, often in the region of the ampulla of Vater. In our series, 65% of the patients had adenomatous polyps of the duodenum or of the ampulla itself. At last follow-up, 4 patients had been operated and none had developed carcinoma of the periampullary region. Our findings are in contradiction with those of Björk et al18 who reported that 5 (2.8%) of 180 patients in the Swedish Polyposis Registry had developed periampullary adenocarcinoma. Those patients were followed over a period of time similar to those in our study but other differences between the 2 study are notable, most notably that the mean age of our patients was less than that in the Swedish study and that in the Swedish surveillance program, endoscopy was performed with the less accurate forward-viewing endoscope, as opposed to the well recognized better side-viewing instrument used in our study. Upper gastrointestinal screening by regular endoscopy with side-viewing instrument is now considered state of the art. Our results seem to indicate that the risk of developing upper gastrointestinal malignancy is less important than it was previously reported.19 Moreover, surgical resection of the ampullary region can prevent the development of adenocarcinoma when patients are found to have stage IV lesions or have difficulties being surveyed for stage III lesions.20

Ileal polyps first described in the ileum immediately proximal to an IR,21,22 in Brooke ileostomies, and in 2 continent ileostomies23,24 have more recently been noted in the ileal pouch after RPC.25–29 In a previous study, we found that 35% of our patients had adenomas in their ileal reservoir.3 In the present study, after at least 11 year of follow-up, 47% of the patients had developed pouch adenomas, but only one had a stage IV lesion. None of our patients have developed carcinoma. This nonexistent risk to develop cancer after at least 11 years of follow-up compares more than favorably with the reported risk of rectal cancer after IR followed for a similar period of time.17

In our series, 13% of patients developed mesenteric desmoid tumors, an incidence similar to that reported previously.8,30 The development of mesenteric desmoids was responsible for the death of 2 of our patients which represents the main cause of death in our entire population of FAP patients treated by RPC. Moreover, functional results were much worse in patients with mesenteric desmoid tumors necessitating an ileostomy in 2 patients.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that RPC eliminates the risk of rectal cancer, that duodenal and ampullary lesions are less worrisome than previously reported as long as close surveillance with a side-viewing instrument is used to detect severe lesions that can be treated more aggressively. Mesenteric desmoid tumors remain the primary cause of death linked to FAP after RPC, and also the principal cause of pouch failure.

Footnotes

Reprints: Dr. Yann Parc, Department of Digestive Surgery, Hôpital Saint-Antoine, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, 184 rue du Faubourg Saint-Antoine, F-75571 Paris, France. E-mail: yann.parc@sat.ap-hop-paris.fr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bulow S, Faurschou Nielsen T, et al. The incidence rate of familial adenomatous polyposis. Results from the Danish Polyposis Register. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1996;11:88–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spigelman AD, Williams CB, Talbot IC, et al. Upper gastrointestinal cancer in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Lancet. 1989;2:783–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parc Y, Olschwang S, Desaint B, et al. Familial adenomatous polyposis: prevalence of adenomas in the ileal pouch after restorative proctocolectomy. Ann Surg. 2001;233:360–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.A. Clark SK, Phillips RKS. Desmoids in familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1494–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Union Against Cancer (UICC). In: Sobin LH, Wittekind Ch, eds. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. 5th ed. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1997:66–69. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newton CR, Baker WN. Comparison of bowel function after ileorectal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis and colonic polyposis. Gut. 1975;16785–16791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Nugent KP, Phillips RK. Rectal cancer risk in older patients with familial adenomatous polyposis and an ileorectal anastomosis: a cause for concern. Br J Surg. 1992;79:1204–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penna C, Tiret E, Parc R, et al. Operation and Abdominal desmoid tumours in familial adenomatous polyposis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1993;177:263–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Cosse JJ, Bulow S, Neale K, et al. Rectal cancer risk in patients treated for familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg. 1992;79:1372–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ambroze W, Dozois RR, Pemberton JH, et al. Familial adenomatous polyposis: results following ileal pouch-anal anastomosis and ileorectostomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:12–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Remzi FH, Church JM, Bast J, et al. Mucosectomy vs. stapled ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis: functional outcome and neoplasia control. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1590–1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bassuini MMA, Billings PJ. Carcinoma in an ileoanal pouch after restorative proctocolectomy for familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg. 1996;83:506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Von Herbay A, Stern J, Herfarth C. Pouch-anal cancer after restorative proctocolectomy for familial adenomatous polyposis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:995–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoehner JC, Metcalf A. Development of invasive adenocarcinoma following colectomy with ileoanal anastomosis for familial polyposis coli. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:824–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vuilleumier H, Halkic N, Ksontinin R, et al. Columnar cuff cancer after restorative proctocolectomy for familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut. 2000;47:732–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malassagne B, Penna C, Parc R. Adenomatous polyps in the anal transitional zone after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for familial adenomatous polyposis: treatment by transanal mucosectomy and ileal pouch advancement. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kartheuser AH, Parc R, Penna CP, et al. Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis as the first choice operation in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis: a ten year experience. Surgery. 1996;119:615–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Björk J, Åkerbrant H, Iselius L, et al. Periampullary adenomas and adenocarcinomas in familial adenomatous polyposis: cumulative risks and APC gene mutations. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1127–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nugent KP, Spigelman AD, Phillips RKS. Risk of extracolonic cancer in familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1121–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Penna C, Bataille N, Balladur P, et al. Surgical treatment of severe duodenal polyposis in familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg. 1998;85:665–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamilton SR, Bussey HJ, Mendelsohn G, et al. Ileal adenomas after colectomy in nine patients with adenomatous polyposis coli/Gardner's syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:1252–1257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iida M, Itoh H, Matsui T, et al. Ileal adenomas in postcolectomy patients with familial adenomatosis coli/Gardner's syndrome. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:1034–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beart RWJr, Fleming CR, Banks PM. Tubulovillous adenomas in a continent ileostomy after proctocolectomy for familial polyposis. Dig Dis Sci. 1982;27:553–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stryker SJ, Carney JA, Dozois RR. Multiple adenomatous polyps arising in a continent reservoir ileostomy. Int J Colorectal. 1987;2:43–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bertoni G, Sassatelli R, Nigrisoli E, et al. First observation of microadenomas in the ileal mucosa of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis and colectomies. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shepherd NA, Jass JR, Duval I, et al. Restorative proctocolectomy with ileal reservoir: pathological and histochemical study of mucosal biopsy specimens. J Clin Pathol. 1987;40:601–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nugent KP, Spigelman AD, Nicholls RJ, et al. Pouch adenomas in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg. 1993;80:1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Church JM, Oakley JR, Wu JS. Pouch polyposis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for familial adenomatous polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:584–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu JS, McGannon EA, Church JM. Incidence of neoplastic polyps in the ileal pouch of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis after restorative proctocolectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:552–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soravia C, Berk T, McLeod RS, et al. Desmoid disease in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:363–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]