Abstract

Objective:

To assess the short and long-term educational value of a highly structured, interactive Breast Cancer Structured Clinical Instruction Module (BCSCIM).

Summary Background Data:

Cancer education for surgical residents is generally unstructured, particularly when compared with surgical curricula like the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) course.

Methods:

Forty-eight surgical residents were randomly assigned to 1 of 4 groups. Two of the groups received the BCSCIM and 2 served as controls. One of the BCSCIM groups and 1 of the control groups were administered an 11-problem Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) immediately after the workshop; the other 2 groups were tested with the same OSCE 8 months later. The course was an intensive multidisciplinary, multistation workshop where residents rotated in pairs from station to station interacting with expert faculty members and breast cancer patients.

Results:

Residents who took the BCSCIM outperformed the residents in the control groups for each of the 7 performance measures at both the immediate and 8-month test times (P < 0.01). Although the residents who took the BCSCIM had higher competence ratings than the residents in the control groups, there was a decline in the faculty ratings of resident competence from the immediate test to the 8-month test (P < 0.004).

Conclusions:

This interactive patient-based workshop was associated with objective evidence of educational benefit as determined by a unique method of outcome assessment.

Evidence exists that medical students and residents are not adequately trained in the management of patients with breast cancer. Surgical residents participated in the Breast Cancer Structured Clinical Instruction Module, a highly structured, interactive patient-based workshop. When tested with an Objective Structured Clinical Examination, the residents who participated in the workshop performed significantly better than residents who had traditional training only. The authors suggest that structured breast cancer education could significantly improve residents’ knowledge and clinical skills in breast cancer management.

Excluding cancers of the skin, breast cancer is the most common cancer among women, accounting for nearly 1 of every 3 cancers diagnosed in women in the United States.1 An estimated 211,300 new invasive cases of breast cancer are expected to be diagnosed among women in the United States in 2003, and an estimated 39,800 deaths from breast cancer are expected to occur. Only lung cancer causes more cancer deaths in U.S. women.1 Despite the importance of breast cancer morbidity and mortality among U.S. women, physician education concerning the diagnosis and management of breast cancer is lacking. Studies suggest that cancer education as it currently exists is not adequately preparing physicians for optimal management of patients with breast cancer.2–4 A survey of graduating medical students found that some of the students had few occasions during medical school to perform such basic a skill as clinical breast examination.5 Another survey of fourth year medical students revealed that most of the students had never palpated the breast of a woman with breast cancer.6

Nevertheless, directors of postgraduate training programs assume that clinical skills such as clinical breast examination, risk assessment, and patient counseling have been acquired in medical school. That may be a false assumption, according to evidence from our institution and other schools.7–9 Only with the development of performance-based testing has the failure of medical schools to teach clinical skills become apparent.7–9

The Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) is a performance-based method for evaluating physicians in training.10–11 In this examination format, trainees encounter patients individually and are asked to perform such tasks as obtaining a history, performing a focused physical examination, or presenting treatment options. As initially described by Harden,10 the OSCE consists of a number of stations through which trainees rotate, spending predetermined amounts of time at each station. Different clinical skills are assessed at each station, and item checklists, completed by faculty proctors or standardized patients (SPs), are used to grade the trainees objectively. The use of both actual and simulated patients as SPs in the OSCE creates a real-life setting for the student or resident.12 The OSCE allows the same clinical problem to be presented to many examinees in a highly structured setting in which objective criteria can be used to evaluate each participant directly. The OSCE, thus, provides a unique window into the clinical ability of individual students or residents.

Studies have demonstrated that the OSCE underscores deficits in oncology-related skills and problem-solving abilities.13–15 Using a multifaceted assessment that included standardized patients, Chalabian et al documented numerous deficits in breast examination, lump detection, and breast cancer problem-solving among senior residents in 7 primary care programs.15 In Canada, confidence in the OSCE as a superior method of performance evaluation has led both the Medical Council of Canada and several specialty boards to include the OSCE in the licensing and certifying examination process.16–17 In the United States, a standardized patient examination will shortly become a critical part of the National Board of Medical Examiners licensing examination.

To determine if the Canadian licensing examinations actually predict performance in subsequent practice, Tamblyn et al tracked the practices of 614 family physicians in the Province of Quebec and evaluated 1,116,389 physician-patient encounters.18 Physicians with lower scores on the Quebec OSCE licensing examination were found to have referred fewer patients to specialists for consultation, prescribed more inappropriate medications to elderly patients, and referred fewer women between the ages of 50 and 69 for mammography screening.18 While it is difficult to measure the impact of poor physician education on breast cancer morbidity and mortality, this landmark study from Canada does link poor performance on a performance-based examination to poor practice patterns down the road.

In an effort to apply standardized comprehensive, skills-based instruction to resident education about breast cancer, a format for teaching important clinical and interpersonal skills was developed. This format, the Breast Cancer Structured Clinical Instruction Module (BCSCIM),19–21 grew out of the observation that immediate feedback given to trainees during the OSCE was very well received.22 The BCSCIM consists of a series of skills-training stations, each devoted to 1 component of the care of the patient with or at risk for breast cancer. During the BCSCIM, expert faculty members and SPs interact with small groups of trainees who rotate from room to room, encountering a different clinical problem or instructional scenario at each station. The instruction at each station is guided by a predetermined written checklist of essential items for that component of care.

Blue, et al examined the effect of the BCSCIM on medical students’ performance on breast stations in an OSCE.21 A total of 89 third-year medical students were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 groups. The first group of students received a traditional lecture on breast cancer diagnosis and management given by a surgical oncologist; the second group of students received a 9-station BCSCIM, a lecture, and a written manual concerning breast cancer management; and the third group of students received a 5-station BCSCIM. Students in the second and third groups performed significantly better on 2 breast stations in a subsequent OSCE (P < 0.05).

The purpose of this study was to determine the effectiveness of the BCSCIM in improving surgery residents’ clinical skills using the OSCE as the method of outcome assessment.

METHODS

A total of 48 general surgery residents from the University of Kentucky were randomly assigned to 1 of 4 groups (stratified by level of training–postgraduate year [PGY] 1–6). Two of the groups received an experimental treatment and 2 served as controls. Residents in the 2 experimental groups received the BCSCIM training, and residents in the 2 control groups received traditional training such as conferences and lectures. One of the BCSCIM groups and 1 of the control groups were administered an 11-problem Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) immediately after the workshop; the other 2 groups were tested with the same OSCE 8 months later.

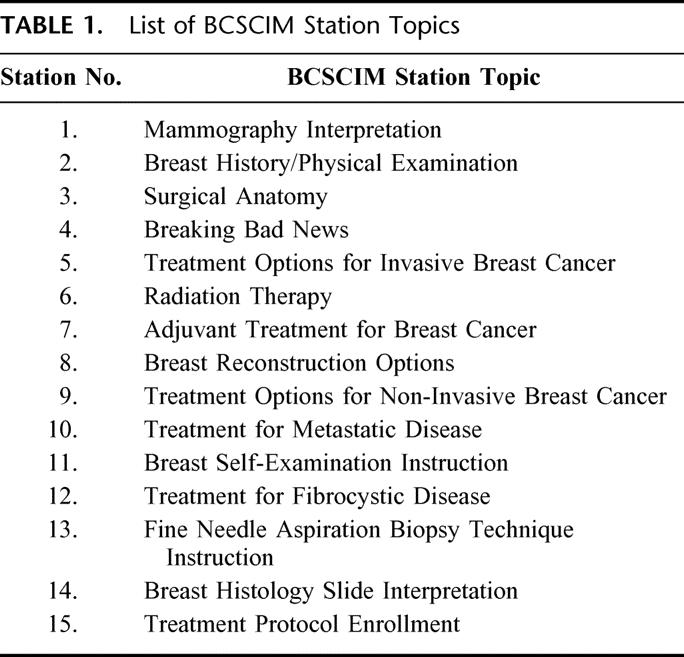

The BCSCIM consisted of 15 stations, each station related to a different aspect of the diagnosis and treatment of breast disease. Residents rotated through the BCSCIM stations in groups of 2, spending 12 minutes in each station. A faculty member was present in each station to guide the instruction, and a SP with whom the residents interacted was present in 12 of the stations. Five of the SPs were actual cancer patients. Over the course of the 15 stations, residents in each pair had equal opportunity to interact with the SPs and faculty. The list of station topics is presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1. List of BCSCIM Station Topics

Following the 3-hour skills course, residents in the immediate post test experimental group were tested on an 11-problem breast cancer Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE). The corresponding control group was also tested at that time. Eight months after the BCSCIM, experimental and control residents in the 8-month post-test groups were tested with the same 11-problem OSCE. No effort was made over the 8-month period to monitor the participating residents’ clinical experiences to determine if some residents had more exposure to patients with breast cancer than other residents.

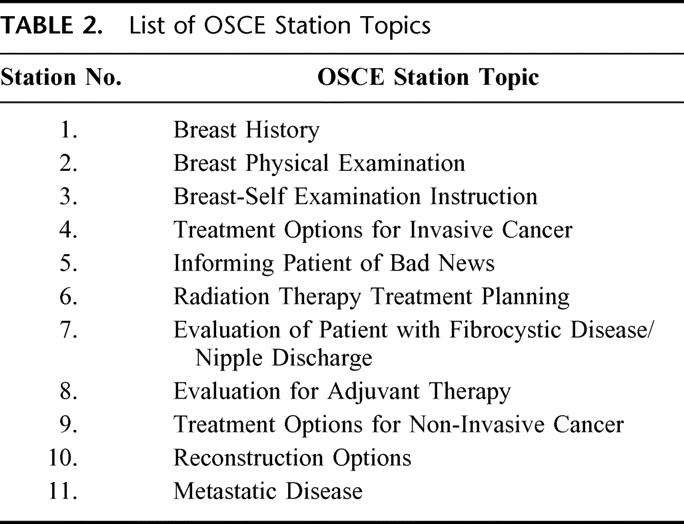

Each OSCE problem consisted of 2 stations, Part A and Part B. In each Part A station, an SP and a faculty proctor were present. Residents rotated through the OSCE stations individually, spending 5 minutes in each station. The resident was graded by the faculty proctor who observed the SP-resident interaction. Residents performed tasks such as obtaining the history from an SP with a complaint of a breast lump and explaining the need for and process involved in radiation therapy to an SP considering breast-conserving treatment of breast cancer. The faculty proctor completed a checklist for each resident by marking each clinical skill item 0, 1, or 2 corresponding to not done, done poorly, or done well. The score received on the clinical skills items was converted to a percent score. In addition to the percent score for the clinical skill checklist items, the residents received 5 additional ratings at each Part A station. Four of these ratings used a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (poor) to 4 (outstanding): (1) an overall global evaluation score as judged by the faculty proctor, (2) an organization score as judged by the faculty proctor, (3) an interpersonal skills score as judged by the faculty proctor, and (4) an interpersonal skills score as judged by the SP. The faculty proctor also judged whether the residents’ performance was competent (1) or not competent (0). Faculty proctors did not know which residents had taken the BCSCIM and which residents had traditional training. The OSCE stations were developed by the members of the working group responsible for the development of the BCSCIM. The second station for each OSCE problem, Part B, consisted of multiple-choice or short-answer questions related to the first station in the pair. Table 2 describes each of the 11 OSCE problems.

TABLE 2. List of OSCE Station Topics

In summary, the residents received 7 scores for each clinical problem: (1) percent of indicated information obtained on the Part A OSCE stations; (2) percent correct of responses to the short answer questions of Part B stations; (3) percent of Part A stations for which the resident was judged competent; (4) faculty proctor evaluation of the residents’ organized approach to the patient (0–4 scale); (5) faculty proctor evaluation of the residents’ interpersonal skills (0–4 scale); (6) faculty proctor overall evaluation of the residents’ performance (0–4 scale); (7) standardized patient evaluation of the residents’ interpersonal skills (0–4 scale).

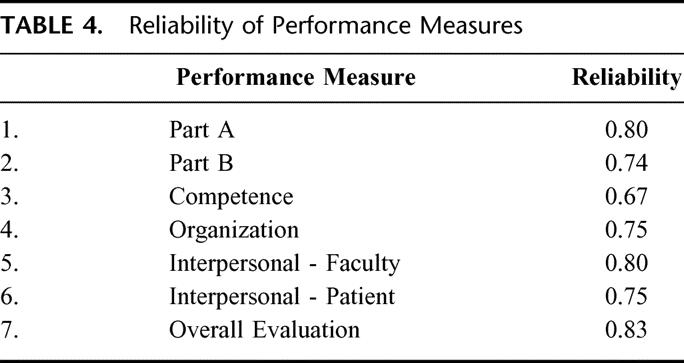

The reliability of the mean score across the 11 OSCEs of each of the 7 scoring scales was estimated by coefficient α.

A 2-way factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on the mean score for each of the 7 performance measures. This statistical design determined if there were significant differences attributable to training (BCSCIM group versus traditional training group) and testing time (immediate test groups and 8-month test groups). Effect sizes are represented as η2. The η2 values can be interpreted using the following criteria: values between 0.01 and 0.05 indicate a small effect; 0.06–0.13 indicate a medium effect; and 0.14 and greater indicate a large effect.23

RESULTS

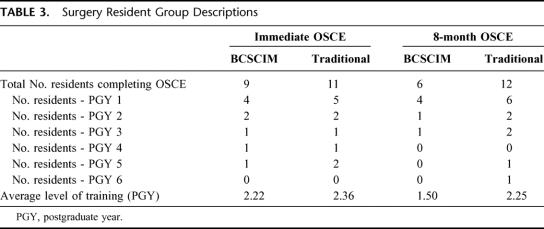

Table 3 presents the number of residents who completed the testing by training and testing conditions. Although 12 residents had been assigned to each of the 4 groups, as can be seen in Table 3, the actual number of residents who completed the testing was less than 12 for 3 of the 4 groups. Attrition was mainly attributable to resident unavailability at the designated testing times because of clinical responsibilities. Table 3 also presents the number of residents in each group by PGY level as well as the average level of training of the residents in terms of postgraduate year (where Intern [PGY-1] = 1, PGY-2 = 2, etc). A 2-way analysis of variance indicated that the average training level of the residents did not vary significantly between the experimental and control groups (P = 0.393), nor between the immediate and 8-month OSCE testing (P = 0.423). Preliminary data analysis identified an inconsistency with the data from 1 Part A station (Breast Self-Examination Instruction). Because of variation attributable to faculty proctors at the 2 separate test times, the authors decided to exclude the data from this Part A station from further analyses.

TABLE 3. Surgery Resident Group Descriptions

Table 4 presents the reliabilities for each of the 7 scoring methods. The reliabilities of (1) the percent of indicated information obtained score; (2) the interpersonal skills score as judged by the faculty proctors; and (3) the overall evaluation were particularly high, in the 0.80s. Only the reliability for the percent competent score was below 0.70.

TABLE 4. Reliability of Performance Measures

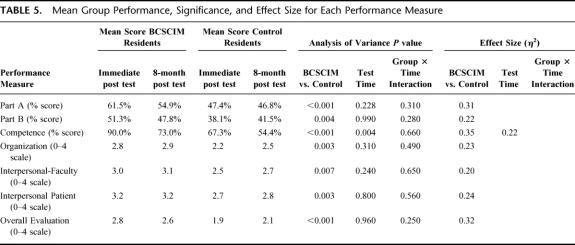

Table 5 presents the mean scores for the 4 groups on each of the 7 performance measures. This table also presents the P-values from the ANOVAs and the corresponding effect-size statistics. Note the P-values representing significant differences have been bolded, and effect size statistics are only reported for those measures for which there was a significant difference. The residents who participated in the BCSCIM performed significantly better than the residents in the control groups (all P < 0.01) for each of the 7 performance measures. The most important group differences (as indicated by the η2 effect size statistics) were in the Part A percent scores (P < 0.001, η2 = .31), the competence ratings (P < 0.001, η2 = .35), and the overall evaluation scores (P < 0.001, η2 = .32).

TABLE 5. Mean Group Performance, Significance, and Effect Size for Each Performance Measure

Table 5 also presents the P-values from the ANOVA testing for differences between testing times. For 6 of the 7 measures there were no indications of decline in performance over time. There was a statistically significant decrease in the percent competent score of residents between the 2 testing times (P = 0.004, η2 = .22). Analyses of simple effects indicated that, for the control group, there was not a significant decrease in the percent competent score (P = 0.07). However, there was a decrease in the percent competent scores of BCSCIM residents between the 2 test times (P = 0.01). Thus, the significance of the main effect decline in the percent competent scores is largely attributable to the experimental group.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to determine the short and long-term effectiveness of a structured breast cancer educational program among a cohort of surgical residents. In this study, one-half of the residents participated in the hands-on skills training course, the BCSCIM, and the other half served as a control group, receiving no education other than the usual lectures, conferences, and rounds experienced during the academic year. The residents who participated in the BCSCIM performed at a higher level than the residents in the control groups on each of the performance measures, both initially and over time.

Very few standards have been set that deal with the clinical evaluation and treatment of cancer patients. This is in marked contrast to patients with acute trauma or cardiac disease, for whose treatment appropriate groups of specialists have laid out and delineated competent behavior: for example, the Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) and Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) programs.24–27 The successful, large-scale ATLS program grew from the subjective impression of a single concerned physician that there was a widespread degree of incompetence in the initial treatment of the injured patient.27 Both the ACLS and ATLS programs have packaged standardized instruction formats and have been successfully administered to hundreds of thousands of physicians, residents, and students. Clinical skills instruction forms an important part of these standardized courses, and this clinical instruction has been found to be most effective for small groups of trainees with a high ratio of instructors to students.26,28 Both programs are associated with improved physician performance and improved patient survival.29–30 Although these programs were originally designed for practitioners, they have since been successfully modified for other audiences such as medical students.28,31–32

The education medical students and residents receive in the evaluation and treatment of cancer patients has not been standardized. The BCSCIM, however, focuses on standardized clinical skills instruction delivered by clinical experts, using a high ratio of instructors to residents. The current study indicates that educational programs such as the BCSCIM have the potential to lead to improved physician performance and improved patient survival.

The BCSCIM format represents an adaptation of the OSCE for clinical teaching; its purpose is to present highly concentrated and structured instruction in clinical skills that are essential to a particular clinical area, in this case breast cancer. These clinical skills are generally not obtained from textbooks, the usual source of information for students and residents. The BCSCIM appears to be a very efficient method for imparting clinical expertise by bringing multiple faculty experts into close contact with small groups of trainees. The use of patients and actual patient materials adds a realism that is difficult to reproduce outside of an actual clinic or ward experience. The BCSCIM has been used for training medicine-surgery clerkship students at our institution for over 6 years. An end-of-the-rotation OSCE has measured a significant beneficial impact on clinical skills related to breast disease among medical students who have participated in the BCSCIM.21

In this study, we have demonstrated that the BCSCIM significantly increases the clinical knowledge and clinical skills of surgical residents in diagnosing and treating patients with breast cancer. However, it should be noted that the BCSCIM training in itself does not produce residents who are fully competent to treat patients with breast cancer. The mean performance ratings in Table 4 clearly show this to be the case. While the mean ratings of the BCSCIM residents are impressively higher than those of the control group, the average ratings on the various scales do not reflect fully competent performance levels. It would be too much to expect that a 3-hour training program could accomplish that goal. Ongoing formal training and assessment are essential for residents to reach satisfactory levels of competence.

The cost involved for the BCSCIM for surgery residents was modest. It primarily consisted of payment to the SPs, approximately $1000 (3-hour involvement in the course plus 1 hour of training for 12 SPs at the rate of $20/h). In addition, breakfast was provided for all participants: the residents, faculty, and staff, costing approximately $300, for a total cost of $1300 for the course.

Aside from the cost in dollars, the issue of faculty hours involved in the BCSCIM must be addressed. A total of 15 faculty members volunteered to participate in the BCSCIM. Because the course was given on a Saturday morning, faculty members were able to participate without interfering with clinical responsibilities. For a total of 3.5 hours per faculty member (3 hours for the course, and 30 minutes preparation time with the course director-DAS), approximately 52 faculty hours were spent on the BCSCIM. To decrease the number of faculty needed to present the course, for later use the course was decreased to 12 stations by combining some station topics.20

It is important to note that in evaluating the BCSCIM, 66 faculty members from the University of Kentucky and other institutions where the course was given over the period of 1 year (1996) were asked how often they would be willing to participate in a similar course in the future. The mean response to this question was 3 times per year (unpublished data), considered to be a very favorable response. In addition, faculty involved in the course strongly agreed that the BCSCIM was a valuable educational experience for the residents.20

One limitation of this study was the small number of residents involved. Due to attrition, the experimental group completed the study with only 15 residents, and these residents were, on average, at an earlier point in their training than the control group residents. The control group consisted of 23 residents at the end of the study. Although it would have been beneficial to test a larger number of residents, it was not possible. Nevertheless, even with a small sample size and the lower level of training of the BCSCIM group, it was possible to detect the effectiveness of the BCSCIM for teaching important clinical skills.

The BCSCIM format was found in this study to be an effective and durable method of educating surgical residents in the care of patients with or at risk for breast cancer.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH Grant CA 66841.

Reprints: David A. Sloan, MD, Department of Surgery, University of Kentucky College of Medicine, 800 Rose Street, Lexington, KY 40536. E-mail: dasloa0@uky.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures, 2003. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society, Inc.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bleyer WA, Hunt DD, Carline JD, et al. Improvement of oncology education at the University of Washington School of Medicine, 1984–1988. Acad Med. 1990;65:114–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernard LJ, Carter RA. Surgical oncology education in US and Canadian medical schools. J Cancer Educ. 1988;3:239–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jewell WR, Deslauriers MP. Teaching surgical oncology to medical students. J Surg Onc. 1983;24:218–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kann PE, Lane DS. Breast cancer screening knowledge and skills of students upon entering and exiting a medical school. Acad Med. 1998;73:904–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kennedy BJ, Foley JF, Yarbro JW, et al. Breast cancer examination experience of medical students and residents. J Cancer Educ. 1988;3:243–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gleeson F. Defects in postgraduate clinical skills as revealed by the Objective Structured Long Examination Record (OSLER). Irish Medical Journal. 1992;85:11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sloan D, Schwartz R, Donnelly M, et al. The use of an Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) to quantify improvement in clinical competence during the surgical internship. Surgery. 1993;114:343–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sloan DA, Donnelly MB, Schwartz RW, et al. Assessing medical students’ and surgery residents’ clinical competence in problem solving in surgical oncology. Ann Surg Oncol. 1994;1:204–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harden RM, Stevenson M, Downie WW, et al. Assessment of clinical competence using Objective Structured Examination. Br Med J. 1975;1:447–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sloan DA, Donnelly MB, Schwartz RW, et al. The Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE): the new gold standard for evaluating resident performance. Ann Surg. 1995;222:735–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson MB, Stillman PL, Wang Y. Growing use of standardized patients in teaching and evaluation in medical education. Teach Learn Med. 1994;6:15–22. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwolek DS, Witzke DB, Blue AV, et al. Assessing the need for increased curricular emphasis on women's health topics in graduate medical education. Acad Med. 1997;72:S48–S50.9347737 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sloan D, Donnelly M, Schwartz R, et al. Measuring the ability of residents to manage oncologic problems. J Surg Oncol. 1997;64:135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chalabian J, Garman K, Wallace P, et al. Clinical breast evaluation skills of house officers and students. Am Surg. 1996;62:840–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brailovsky CA, Grand'Maison P, Lescop J. A large-scale multicenter objective structured clinical examination for licensure. Acad Med. 1992;67:S37–S39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reznick RK, Blackmore D, Cohen R, et al. An objective structured clinical examination for the licentiate of the medical council of Canada: from research to reality. Acad Med. 1993;68:S4–S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamblyn R, Abrahamowicz M, Brailovsky C, et al. A positive association between licensing examination scores and selected aspects of resource use and quality of care in primary care practice. JAMA. 1998;280:989–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sloan DA, Donnelly MB, Plymale M, et al. The Structured Clinical Instruction Module as a tool for improving students’ understanding of breast cancer. Am Surg. 1997;63:255–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sloan DA, Donnelly MB, Plymale MA, et al. Improving residents’ clinical skills with the Structured Clinical Instruction Module (SCIM) for breast cancer. Surgery. 1997;122:324–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blue A, Stratton T, Plymale M, et al. The effectiveness of the Structured Clinical Instructional Module as an instructional format. Am J Surg. 1998;176:67–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sloan DA, Donnelly MB, Schwartz RW, et al. The use of the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) for evaluation and instruction in graduate medical education. J Surg Research. 1996;63:225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence-Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carveth SW, Burnap TK, Bechtel J, et al. Training in advanced cardiac life support. JAMA. 1976;235:2311–2315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaye W, Mancini ME, Rallis SF. Advanced cardiac life support refresher course using standardized objective-based Mega Code testing. Crit Care Med. 1987;15:55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collicott PE. Advanced trauma life support course, an improvement in rural trauma care. Nebr Med J. 1979;64:279–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collicott PE. Advanced trauma life support (ATLS): past, present, future- 16th Stone Lecture, American Trauma Society. J Trauma. 1992;33:749–753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tintinalli J, Freeman S, Kalia S, Laubscher. Advanced cardiac life support training for medical students and house officers. J Med Educ. 1984:59:200–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ali J, Adam R, Butler AK, et al. Trauma outcome improves following the advanced trauma life support program in a developing country. J Trauma. 1993;34:890–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lowenstein SR, Sabyan EM, Lassen CF, et al. Benefits of training physicians in advanced cardiac life support. Chest. 1986;89:512–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mehne PR, Allison EJ, Williamson JE, et al. A required, combined ACLS/ATLS provider course for senior medical students at East Carolina University. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:666–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sloan D, Brown R, Macdonald W, et al. Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS): is there a definitive role in undergraduate surgical education? Focus on Surgical Education. 1988;5:12. [Google Scholar]