Abstract

Objective:

We sought to develop a comprehensive program for clinical genetic testing in a large group of extended families with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN 1), with the ultimate aim of early tumor detection and surgical intervention.

Summary Background Data:

Germline mutations in the MEN1 tumor suppressor gene are responsible for the MEN 1 syndrome. Direct genetic testing for a disease-associated MEN1 mutation is now possible in selected families. The neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas/duodenum and the intrathoracic neuroendocrine tumors that occur in MEN 1 carry a malignant potential. Importantly, these tumors arise in otherwise young healthy patients and are complicated by the potential for multifocality and involvement of multiple target tissues. The optimal screening methods and indications for early surgical intervention in genetically positive patients have yet to be defined.

Methods:

Nine MEN 1 kindreds were included in the study. The mutations for each kindred were initially identified in the research laboratory. Subsequently, mutation detection was independently validated in the clinical Molecular Diagnostic Laboratory. Each patient in the study underwent formal genetic counseling before testing.

Results:

Genetic testing was performed in 56 at-risk patients. Patients were stratified according to risk: Group I (n = 25), 50% risk, younger than 30 years old; Group II (n = 20), 50% risk, 30 years old or older; Group III (n = 11) 25% risk. Seven patients (age, 12 to 42 years; mean, 20.6 ± 3.8 years) had a positive genetic test. Patients with a novel positive genetic test were in either Group I (n = 6) or Group II (n = 1) and have been followed for 35.8 ± 2.0 months. Of the 7 genetically positive patients, hypercalcemia was either present at the time of diagnosis or developed during the period of follow-up in 6 patients. Four patients have undergone parathyroidectomy as early as age 16 years. One genetically positive patient has not yet developed hyperparathyroidism. Intensive biochemical screening in this select group of patients identified an elevated pancreatic polypeptide level and pancreatic tail mass lesion in a 15-year-old male who is asymptomatic and currently normocalcemic.

Conclusions:

Genetic testing identifies patients harboring an MEN1 mutation before the development of clinical signs or symptoms of endocrine disease. When genetically positive patients are carefully studied prospectively, biochemical evidence of neoplasia can be detected an average of 10 years before clinically evident disease, allowing for early surgical intervention. Genetically positive individuals should undergo focused cancer surveillance for early detection of the potentially malignant neuroendocrine tumors that account for most of the disease-related morbidity and mortality.

Genetic testing can identify patients affected with MEN 1 before the development of clinical signs and symptoms of endocrine disease, allowing for early surgical intervention. Genetically positive patients should undergo focused screening for the early detection and removal of the potentially malignant neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas and duodenum.

The multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN 1) syndrome is characterized by the development of hyperparathyroidism due to multiglandular parathyroid disease (95% to 100% of patients), benign and malignant neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas and duodenum (35% to 75%), and adenomas of the anterior pituitary (15% to 30%). Other neoplasms associated with MEN 1 include foregut (thymic and bronchial) carcinoids, multiple lipomas, nodular adrenocortical hyperplasia, cutaneous angiofibromas, and ependymomas of the central nervous system.

The clinical expression of endocrine disease in patients with MEN 1 most often begins in the third or fourth decade, with the onset of overt disease being rare before age 10 years.1 In keeping with its autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, males and females are affected equally. The MEN 1 syndrome has been described in diverse geographic regions and ethnic groups, and no racial predilection has been demonstrated. Endocrine tumors in patients with MEN 1 cause symptoms either due to overproduction of a specific hormone or the local mass effects and/or malignant progession of the neoplasm. Previously, complications related to hormone excess, such as severe ulcer disease or hypoglycemia, were the most frequent presenting complaints2 and not infrequently resulted in patient deaths. Currently, the principal cause of mortality in patients with MEN 1 is the malignant progression of the neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas, duodenal gastrinomas, and thymic or bronchial carcinoids.3,4

Unique characteristics of neoplasms that arise in association with an inherited cancer syndrome include a preneoplastic hyperplasia within the affected tissue (eg, islet cell hyperplasia), the development of multiple tumors within a target tissue, and the potential for development of tumors in more than 1 target tissue. Furthermore, in the setting of a familial cancer syndrome, patients develop tumors at a much younger age than patients who develop sporadic tumors of the same tissue type. In keeping with the “two-hit” model of tumorigenesis for a putative tumor suppressor gene, this earlier age-of-onset is due to the fact that 1 mutation is inherited in the germline and only 1 other event is necessary to inactivate the remaining wild-type allele and result in tumor initiation. Therefore, patients inheriting an MEN1 gene mutation have a propensity to develop multiple tumors at a young age when they are otherwise healthy and active. Although many of these endocrine neoplasms are either benign or may follow an indolent course, a subset may metastasize early to regional lymph nodes, liver, or distant sites and be life-limiting. The clinical management of these tumors is complicated by the difficulty in localizing small tumors early on routine imaging tests, the relative lack of specific and sensitive tumor markers for, and uncertainty about the expected natural history of small tumors. Most importantly, in contrast to other familial cancer syndromes and the tissue at principal malignant risk, such as multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (thyroid) and familial adenomatous polyposis (colon), a prophylactic total extirpation of the target tissue at most risk for malignant change (pancreas) carries inordinate risk of morbidity and mortality in an otherwise young, healthy patient.

Germline mutations in the MEN1 tumor suppressor gene are responsible for the MEN 1 syndrome.5 The MEN1 tumor suppressor gene encodes a 610 amino acid protein product termed menin. Menin is expressed in diverse tissues, including lymphocytes, pancreas, brain, and testes, and it is highly conserved evolutionarily. Menin is predominately a nuclear protein6 that has been shown to bind to JunD (a member of the AP-1 transcription factor family), as well as other proteins, and it is postulated to repress JunD-mediated transcription.7,8 The specific tumor-suppressing role of menin has not yet been elucidated.

The disease-associated germline mutations that occur in the MEN1 tumor suppressor gene are diverse and include missense, nonsense, frameshift, deletion, and mRNA splicing defects which may be dispersed throughout the coding and noncoding (intronic) portions of the gene.9–13 Furthermore, there are almost as many unique mutations as there are families reported with MEN 1. To date, over 300 specific germline mutations have been described in families with MEN 1.14 The diverse nature of MEN1 disease mutations has important implications for the development of a comprehensive clinical genetic test.

We sought to develop a comprehensive program for clinical genetic testing in a large group of MEN 1 families, with the ultimate aim of early tumor detection and surgical intervention. The essential components this study include translation of molecular genetic findings in the research laboratory to an accredited clinical Molecular Diagnostic Laboratory and the development of a program of formal genetic counseling for all participants. Genetically positive patients undergo focused biochemical screening for development of the most clinically significant tumors, with the aim of early tumor detection and surgical intervention.

METHODS

The total study population comprises 9 extended MEN 1 kindreds representing a total of 921 individuals (63 known affected; 411 at ≤ 50% genetic risk) that have been followed prospectively by the Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Program at Washington University School of Medicine. Many of the 411 members at ≤ 50% risk are either older than age 30 years without clinical manifestations of disease and are therefore unlikely to be affected or live some distance from the study location and would have significant difficulty in complying with all visits required for genetic counseling, informed consent, blood drawing, and reporting of results. Therefore, for the purposes of this initial translational study, we identified a subset of the entire study population that is followed most closely by our ongoing research program. This subset of family members was chosen on the basis of the availability of multiple generations, including at-risk individuals and geographic proximity to the medical center to facilitate the necessary visits to complete the study. The genetic mutations for each kindred included in the study were initially identified in the research laboratory.13 Subsequently, mutation detection was independently validated in the Clinical Molecular Diagnostic Laboratory. Patients were entered into the study under an Institutional Review Board–approved protocol (Washington University Human Studies Committee #98–0576), and each underwent formal genetic counseling before genetic testing.

The at-risk members of these selected families were contacted by letter about the opportunity for genetic testing through the research protocol. Interested individuals had 1 or more genetic counseling sessions to review the clinical manifestations of MEN 1 and to discuss the associated tumor risks. The specific issues addressed during these meetings included the pattern of inheritance of MEN 1, the personal risk for tumor development, screening recommendations for affected individuals and their children, and the benefits and limitations of genetic testing. Despite an agreement not to release the information to third parties, issues relating to privacy of medical information and the potential impact on the ability to obtain medical insurance after a genetic diagnosis were also discussed. After informed consent was obtained, blood was drawn for the genetic studies as well as screening biochemical studies. Individuals were notified by letter when results of genetic testing were available and asked to return for disclosure of test results. If a patient did not initiate a return visit, a second follow-up letter was sent indicating the need to contact the office to receive their results. In the event that a patient finally elected not to learn the results of the genetic test, continued annual biochemical surveillance was recommended.

During the translational phase of the study, the clinical Molecular Diagnostic Laboratory screened 69 family members from 10 kindreds for 8 different germline mutations in the MEN1 gene. These numbers include known affected patients serving as positive controls. All clinical blood specimens were redrawn after genetic counseling and informed consent, and obtained independently from the specimens banked in the research laboratory. Eleven individuals had identification of specific mutations in the MEN1 gene; in each case, the identified genetic change was consistent with the familial mutation previously characterized familial mutation. Most mutations were previously identified in the research laboratory and were detected by direct DNA sequencing of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products produced by flanking amplification primers and validated in the clinical laboratory using material from known MEN 1–affected family members. One family (K013) was screened by genomic Southern hybridization to identify a deletion in the 5′ flanking region that created a restriction fragment length change in a SacI segment (unpublished observation).

DNA was isolated using the PureGene system (Gentra Systems, Inc. Minneapolis, MN) from peripheral blood specimens collected in ACD vacutainer tubes transported at ambient temperature. DNA fragments were amplified by PCR using primers as previously defined (ref) and the TaqPCR Master Mix kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA). PCR products were processed through Wizard columns (Promega, Madison, WI) to remove unincorporated primers and nucleotides before direct DNA sequencing using the Big Dye chemistry (ABI, Foster City, CA). DNA sequence reactions were analyzed on an ABI 373 instrument. SacI (New England Biolabs, Beverley, MA) digestion of 10 μg of genomic DNA was separated by electrophoresis in 1% agarose. Fragments were transferred to nylon membranes (Zeta-Probe GT; BioRad, Hercules, CA) and hybridized to a radiolabeled (Rediprime II; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) 0.7 kb SacI-KpnI subfragment of the 5′ region of the genomic menin gene (unpublished). Autoradiograms were obtained using XOMAT XAR5 x-ray film (Kodak, Rochester, NY).

RESULTS

Fifty-six at-risk individuals elected to undergo genetic testing as part of the research protocol (ages, 12 to 62 years; mean, 30.1 ± 1.9 years). An additional 7 individuals received genetic counseling but did not pursue testing. Four of these individuals (siblings) were lost to follow-up, 1 declined because of lack of insurance, and 2 declined after their at-risk parent tested negative.

Forty (71%) of the 56 patients returned for disclosure and discussion of results. Ten patients were informed via telephone due to limitations of transportation or lack of interest in further discussions concerning their results. Six patients (11%) never recontacted the office to be informed of their results and could not be reached for follow-up. Significantly, 5 of these patients were age 30 years or older and had indicated at the time of consent that they presumed they were negative on the basis of their age. The final patient was lost to follow-up. All 6 of these patients did, in fact, test negative.

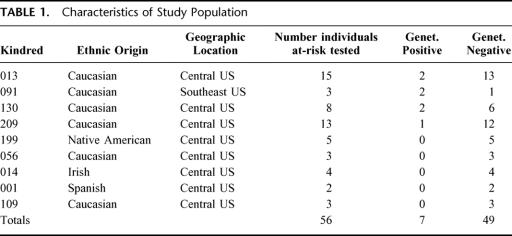

The characteristics of the study population, including ethnic origin, geographic location, numbers of individuals tested, and frequency of genetically positive and negative individuals are depicted in Table 1. The majority of family members included in this initial study are from the central United States, although diverse ethnic backgrounds are represented.

TABLE 1. Characteristics of Study Population

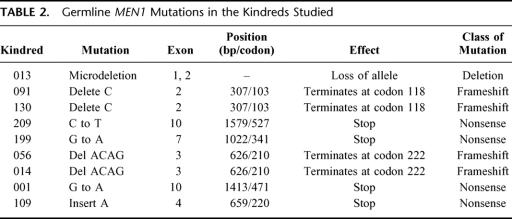

In most cases, the specific MEN1 gene mutations were previously identified in the research laboratory.13 The type of gene alteration in the MEN1 gene detected in this study population includes nonsense, insertion, deletion, and frameshift mutations (Table 2). Nonsense mutations create a stop codon. Insertion or deletion mutations involve the inappropriate addition or deletion ≥ 1 nucleotide bases. Frameshift mutations result from an alteration that changes the triplet reading frame (such as insertion or deletion mutations that are not multiples of 3), resulting in several inappropriate (nonsense) amino acids before a stop codon is encountered. Approximately two thirds of MEN1 gene mutations result in premature termination of translation or truncation of the protein product. The mutation in kindred 013 involves a microdeletion of approximately 7 kb of genomic DNA encompassing the 5′ upstream elements as well as exons 1 and 2 of 1 allele of the MEN1 gene (unpublished results). The distribution of these mutations within the MEN1 gene coding sequence is shown in Figure 1.

TABLE 2. Germline MEN1 Mutations in the Kindreds Studied

FIGURE 1. The distribution of germline mutations along the MEN1 gene sequence in the study kindreds is shown. The MEN1 gene spans approximately 10 kb of genomic DNA and is made up of 10 exons (open rectangles). Exon 1 and the 3′ end of exon 10 are untranslated (shaded rectangles). The deletion, insertion, and nonsense mutations are depicted below the figure. The nomenclature is consistent with the recommendations from the Nomenclature Working Group (Antonarakis et al, 1998). The insertion and deletion mutations are numbered according to the nucleotide at which they occur relative to the A of the open reading frame. The nonsense mutations are numbered according to the codon in which they occur relative to the start methionine residue. The underlining denotes mutations that occur in more than 1 family. The specific mutations are further described in Table 2. Kindred 013 has an approximately 7-kb microdeletion of 1 allelic copy of the MEN1 gene encompassing the upstream 5′ region, exon 1, and most of exon 2 (data not shown) as depicted above the figure. (Modified from Hum Mutat 1999;13:175–185)

Patients were stratified according to risk: Group I (n = 25), 50% risk, younger than 30 years old; Group II (n = 20), 50% risk, 30 years old or older; Group III (n = 11), 25% risk. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 is an autosomal dominant Mendelian trait. Accordingly, males and females are affected equally. Individuals with an affected parent (or a known affected sibling) are at 50% risk of inheriting a disease-associated mutation. Individuals with an affected grandparent, aunt, or uncle (but unknown affected status of parent) are at 25% risk. Patients were stratified according to the groups above, because patients older than 30 years of age who have not yet developed symptoms or have been diagnosed with a component of the MEN 1 syndrome are less likely to test positive. Seven patients (age, 12 to 42 years; mean, 20.6 ± 3.8 years) had a positive genetic test. All patients with a novel positive genetic test were in Group I (n = 6) or Group II (n = 1). The follow-up period for these patients is 28.0 to 46.1 months (mean, 35.8 ± 2.0 months). Genetically positive patients undergo at least annual biochemical screening, including measurement of total or ionized serum calcium, intact parathyroid hormone, prolactin, and fasting gastrin and pancreatic polypeptide. Patients with positive biochemical markers or clinical signs or symptoms undergo selected imaging tests. A pancreas protocol computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) scan is initially obtained, followed by a somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (octreotide) scan or endoscopic ultrasound as indicated by clinical criteria.

For the 7 mutation positive patients, hypercalcemia was either present at the time of genetic diagnosis or developed during the period of follow-up in 6 patients. Four patients have undergone parathyroidectomy as early as age 16 years. One patient has not yet developed hyperparathyroidism (age 15 years), and 2 additional patients currently refuse parathyroidectomy.

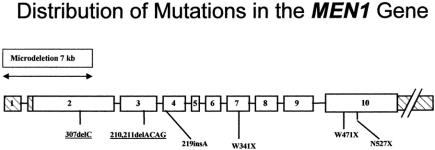

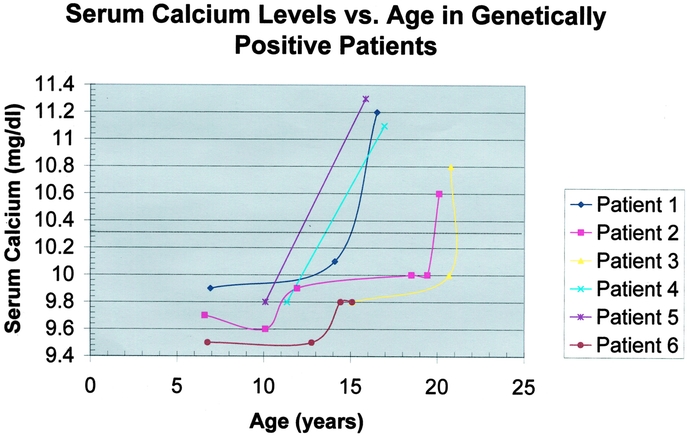

Four patients in the study group underwent neck exploration and parathyroidectomy at ages 16, 18, 19, and 23 years based on the results of genetic testing and/or clinical diagnosis of hyperparathyroidism. Nineteen (95%) of 20 parathyroid glands were identified at the time of initial neck exploration. One patient had identification of only 3 glands at the time of initial neck exploration, including performance of a transcervical partial thymectomy. He subsequently had the successful localization and removal of a deep mediastinal parathyroid tumor at a second operation. Three patients were treated with subtotal (3.5 gland) parathyroidectomy, and 1 patient underwent total parathyroidectomy with heterotopic autotransplantation. The mean weight of parathyroid glands removed was 139.9 ± 116.0 mg (range, 20 to 410 mg). Three (75%) of the 4 patients remain normocalcemic, including the patient requiring 2 operations to identify all 4 glands. One patient (25%) now has recurrent hypercalcemia 3 years after a subtotal parathyroidectomy and an initial period of normocalcemia (Patient 5). The serum calcium levels versus age preparathyroidectomy and postparathyroidectomy are depicted in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2. Serum calcium levels versus age in the 4 genetically positive patients undergoing parathyroidectomy are depicted graphically. Each patient's curve is represented by a different color and data point symbol according to the legend in the upper right corner. Serum calcium level (mg/dL) is plotted as a function of age (years). The upper limit of normal for calcium is indicated by the dotted line. The colored arrows indicate the time of parathyroidectomy for each patient. Patient 1 had identification of 3 glands in the neck at initial exploration and subsequently had successful removal of a deep mediastinal parathyroid gland at a second operation. Patient 5 has recurrent hypercalcemia following a 3.5-gland subtotal parathyroidectomy and an initial period of normocalcemia. All other patients are normocalcemic off all calcium and vitamin D supplementation at the final end point.

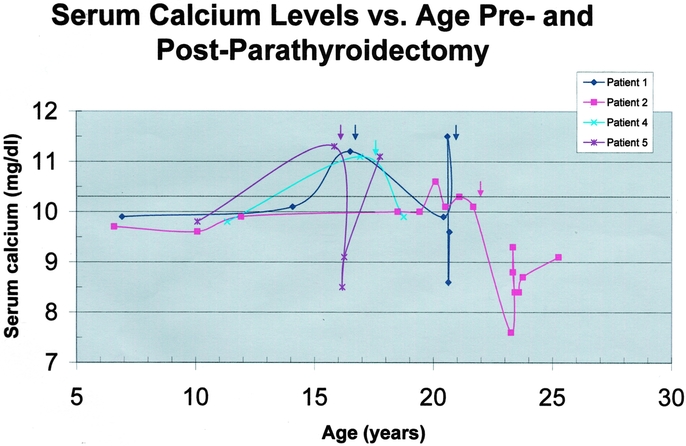

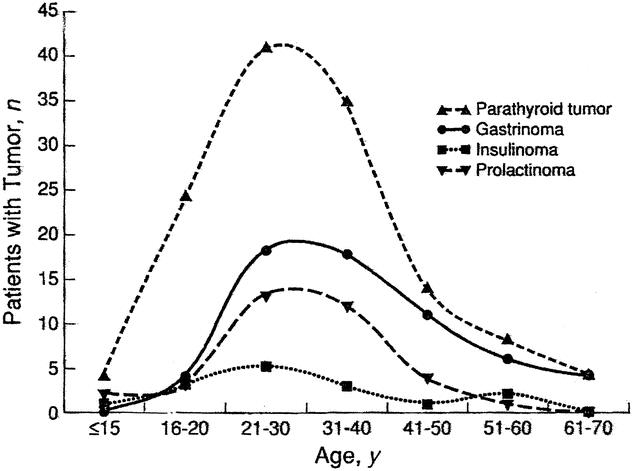

The ability to identify patients harboring MEN1 gene mutation by direct genetic testing allows prospective screening for the biochemical detection of endocrine tumor development. Figure 3 graphically displays total serum calcium levels as a function of age in 6 of the 7 patients with a genetic diagnosis of MEN 1 (the 7th patient has hypercalcemia originally detected at the age of 40 years with no prior data). Of note, when studied prospectively, serum calcium levels are seen to rise rapidly between the ages of 10 and 15 years. Retrospective analysis1 of large numbers of MEN 1 patients has shown the most rapid onset of clinical manifestations of hyperparathyroidism to occur between the ages of 15 and 20 years (Figure 4). In the select group of MEN1 mutation–positive patients in this study, longitudinal data are available for calcium levels before the development of overt clinical symptoms or renal or bone disease. Not surprisingly, the onset of hypercalcemia can be seen to occur an average of 5 years before detection by clinical means or the time of a first positive screening test.

FIGURE 3. Serum calcium levels versus age in 6 of the 7 the genetically positive patients. Patient 7 has data only from ages 40 and 43 years. This patient is hypercalcemic but currently declines parathyroidectomy. Each patient's curve is represented by a different color and data point symbol according to the legend in the upper right corner. Serum calcium level (mg/dL) is plotted as a function of age (years). The upper limit of normal for calcium is indicated by the dotted line. In this selected subset of genetically positive patients followed prospectively, a rapid rise in calcium levels is evident between the ages of 10 and 15 years.

FIGURE 4. Age of onset of endocrine tumor expression in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN 1). Data derived from retrospective analysis for each endocrine organ hyperfunction in 130 cases of MEN1. Age at onset is the age at first symptom or, with tumors not causing symptoms, age at the time of the first abnormal finding on a screening test. The rate of diagnosis of hyperparathyroidism increased sharply between ages 16 and 20 years. (Reprinted with permission from Ann Intern Med 1998;129:484–494)

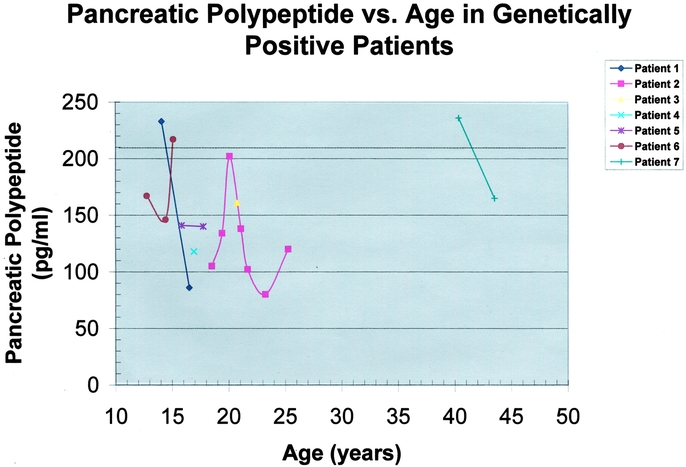

More importantly, prospective biochemical screening for the potentially malignant neuroendocrine tumors in this select group of patients has revealed an elevated pancreatic polypeptide level15,16 in a 15-year-old genetically affected male (Patient 6) who is asymptomatic and currently normocalcemic. CT scanning of the pancreas reveals an approximately 1-cm enhancing mass lesion of the tail of the pancreas consistent with a neuroendocrine tumor. This patient also has a pituitary prolactinoma for which he is undergoing medical therapy. Resection of the pancreatic tail mass has been recommended and is being deferred for a short time by the parents owing to social concerns. The early detection of a pancreatic endocrine tumor in this patient precedes by approximately 10 years the average onset of the clinical manifestations of pancreatic neoplasms (Fig. 4) in patients with MEN 1 from larger retrospective study populations.

DISCUSSION

The optimal management of the potentially malignant duodenopancreatic and intrathoracic neuroendocrine tumors that occur in association with the MEN 1 syndrome remain controversial. The recent identification of disease-associated germline mutations in the MEN1 tumor suppressor gene has allowed the development of direct genetic testing for selected at-risk family members. This test may be performed from a single peripheral venous blood sample that may be obtained at any age. The advent of a genetic test for MEN 1 places new emphasis on a number of dilemmas surrounding the use of the diagnostic information once it is known. The appropriate clinical application of a positive genetic test result requires an understanding of the natural history and malignant potential of the endocrine tumors arising in association with MEN 1 and consideration of the relative potential morbidity and mortality of preemptive surgical intervention. As previously emphasized, there are several unique aspects of neoplastic change associated with hereditary cancer syndromes, including the preneoplastic hyperplasia and multifocal tumor development within a target tissue and potential for multiple tumor types. Importantly, these changes typically occur in otherwise healthy young patients, and all tumors do not carry the same risks of morbidity from hormone oversecretion or malignant dissemination.

The clear focus for early diagnosis and intervention in patients harboring MEN1 mutation should be the potentially malignant neuroendocrine tumors that account for most of the disease-related morbidity and mortality.3,4 Controversy currently exists regarding the best methods for cancer screening, the optimal timing for intervention, and the most appropriate surgical procedure to perform when tumors are detected.17 Because major pancreatic resection carries operative risks of morbidity and small but measurable risks of mortality, it is difficult to advocate extensive pancreatic surgery for small, benign, clinically insignificant tumors. On the other hand, some tumors can clearly metastasize early to regional lymph nodes, liver, or distant sites. Delay in diagnosis of these neoplasms can adversely affect patient survival. Total pancreatectomy as a preemptive operation would uniformly result in complete exocrine and endocrine insufficiency and is not appropriate for patients with MEN 1 who are at risk for developing pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, some of which will prove to be benign or follow an indolent course. The ideal surgical procedure would remove the malignant risk, while preserving endocrine and exocrine pancreatic function and minimizing morbidity and mortality from either the treatment or disease. The issue of identifying those neuroendocrine neoplasms that are associated with a high malignant risk is further complicated by the apparent lack of correlation between maximum size of the largest tumor and the incidence of metastases.18 The current study demonstrates that neoplastic development can be detected biochemically 5 to 10 years before the development of clinical symptoms. Others have previously shown ability to detect biochemical changes before clinically overt tumor development and have advocated early intervention.19–20 These findings highlight the need for sensitive and specific screening tests, and the adoption of a directed clinical management plan that balances early intervention with low morbidity. Possible solutions to these dilemmas include minimally invasive (laparoscopic) intervention for small tumors, preserving pancreatic function, in the setting of a longitudinal program of continued surveillance for new tumor development.

Pancreatic polypeptide has been described as a potential tumor marker for neuroendocrine neoplasms.15 The pancreatic polypeptide level lacks specificity and to some degree sensitivity, but it is useful when markedly elevated. We recently reported that patients with a markedly elevated pancreatic polypeptide level (greater than 3 times normal) almost uniformly have an imageable and therefore clinically significant duodenopancreatic tumor.16 The data in Figure 5 emphasize the fluctuating levels of pancreatic polypeptide over time in individual patients. All genetically positive patients underwent additional testing, including fasting gastrin and fasting glucose and/or insulin measurements. These additional markers for endocrine pancreatic disease were negative (data not shown).

FIGURE 5. Serum pancreatic polypeptide levels versus age in the 7 genetically positive patients. Each patient's curve is represented by a different color and data point symbol according to the legend in the upper right corner. The pancreatic polypeptide level (pg/ml) is plotted as a function of age (years). The upper limit of normal for pancreatic polypeptide is dependent upon age and sex, but an average value for the age range plotted is indicated by the dotted line. Pancreatic polypeptide levels fluctuated significantly over time. No clear pattern or trend of progressive elevation was noted in this small subset of patients. Patient 6 had an elevated pancreatic polypeptide level detected at age 15 years. Computed tomography (CT) scanning in this patient reveals a probably neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreatic tail.

Patients who have a negative genetic test can be spared continued annual clinical testing and are not at risk to pass a mutation on to their children. However, the impact of a positive genetic test on the management of the parathyroid disease that develops in 95 to 100% of MEN 1 patients is minimal. The parathyroid neoplastic change in MEN 1 is not malignant, and patients are followed until they become hypercalcemic before recommending surgical intervention. The results of parathyroidectomy in the select group of patients reported here are in keeping with larger published series. Nineteen (95%) of 20 parathyroid glands were identified at the time of initial exploration. The 25% incidence of recurrent hyperparathyroidism in this study is similar to the 23 to 50% incidence in previous reports.21–24 Patients with MEN 1 have a germline genetic mutation present in every parathyroid chief cell; therefore, parathyroid tissue is at risk for developing subsequent neoplastic change whether left in situ in the neck or autotransplanted to the forearm muscle.

Several ethical issues of genetic testing deserve discussion. The discovery of specific genetic findings can carry risk of significant family ramifications and psychological overtones, including rare cases of nonpaternity, feelings of guilt, issues surrounding privacy of medical information and insurability, and the possibility that establishing an individual's genetic result will provide inferred information pertaining to other family members that they do not wish to learn. Individuals at 25% risk were allowed to participate, although concern was raised regarding the possibility that a positive test result would disclose their parent's positive mutation status. Some of the individuals at 25% risk elected testing the same day as their at-risk parent in the interest of not having to return for another visit in the event their parent tested positive. However, all individuals at 25% risk tested negative, reflecting their parents’ presumed negative mutation status given their older age and asymptomatic state at the time of testing.

The legal and ethical issues surrounding privacy of medical information and insurability for patients with a genetic diagnosis are complex and beyond the scope of this discussion. However, the significance of these concerns is emphasized by the relatively high attrition for patients initially expressing an interest in the study. For example, 7 individuals received genetic counseling but did not pursue testing, and only 40 (71%) of the 56 patients initially entered into the study returned for disclosure and discussion of results. The reasons for failure to follow through with receiving a testing result are almost certainly multifactorial, but concerns regarding insurability and family issues were likely contributory.

Preclinical testing of children is controversial for some genetic diagnoses. Minors over the age of 12 years were included in this study, as this age correlates with the age recommended to initiate biochemical screening. In the event a child has a negative genetic test, they would not need continued screening. There was not felt to be any benefit in testing children under the age of 12 years at the time of initiation of the study because there would be no change in their current medical management. In Groups I and III, there were 7 and 4 individuals, respectively, under the age of 18 years who elected genetic testing. Four (57%) of the 7 individuals younger than 18 years in Group I tested positive. Two (11%) of the 18 individuals aged 18 to 30 years in Group I tested positive. The difference in these numbers among individuals in Group I reflects the likelihood that more individuals in their twenties have already been detected symptomatically; relatively few of the patients in their teens have presented with symptoms, thus the younger group more closely reflects the expected mutation detection rate of 50%.

Our data strongly support the initiation of genetic testing for MEN 1 in the second decade of life, beginning around age 10 or 11 years. This recommendation is supported by the results of prospective, longitudinal biochemical testing in this age group. The biochemical onset of hyperparathyroidism is between ages 10 and 15 years; more importantly, a 15-year-old patient in this study population has already developed an elevated tumor marker and probable neuroendocrine pancreatic tumor. Although no clinical signs or symptoms of endocrine pancreatic neoplasia would be expected in this age group, early detection provides the opportunity for early surgical intervention to prevent subsequent tumor growth and possible malignant dissemination.

CONCLUSION

Genetic testing identifies patients harboring an MEN1 mutation before the development of clinical signs or symptoms of endocrine disease. When genetically positive patients are carefully studied prospectively, biochemical evidence of neoplasia can be detected as early as 5 to 10 years before clinically evident disease, allowing for early surgical intervention. Genetically positive individuals should undergo focused cancer surveillance for early detection of the potentially malignant neuroendocrine tumors that account for most of the disease-related morbidity and mortality.

Discussions

Dr. John B. Hanks (Charlottesville, Virginia): This is an outstanding presentation by a world class group of investigators. The Washington University group has been at the cutting edge of the use of genetic testing to diagnose and surgically approach inherited diseases for over 10 years. Dr. Wells’ landmark report on the applicability of finding a ret-oncogene as a positive predictor for medullary carcinoma of the thyroid in MEN 2 kindreds was reported in 1993. This group has continued that series of outstanding clinical research and applied their findings to MEN 1 patients with this report.

I would like to thank Dr. Lairmore for letting me see the manuscript in advance. My questions really represent that ability to peek at the complete work. I would like to address a couple of questions to the group if I could.

You mention that the potential malignancy of the MEN 1 group is going to occur in the pancreas if at all. Yet those of us with experience in MEN 1 patients have and will encounter patients with clearly malignant lesions. What can or will be done to further predict tumor growth in these patients? Do you predict that the aggressive metastatic tumors might have any apparent mutational changes amongst the complex array of changes that you describe and can this be measured in the future?

My next question is, what is the cost of the complete screening that you outline here and how do you propose to measure over periods of time the cost effectiveness of this kind of testing?

My next question deals with the question of patient confidentiality which is increasingly important for these kinds of studies. In the patients that have positive genetic testing, how do you document the need for your protocol-driven testing including CT, MRI, and octreotide scans and who owns that information, who knows about the results?

Next, you state that 56 patients underwent genetic testing, of which 7 were positive. All of these 7 had accompanying hypercalcemia or it occurred at a short time after their testing. How many of the other 49 had hypercalcemia or an elevated PTH level or had clinically important hypercalcemia? What statistical advantage does a positive genetic test have over the initial calcium PTH or even the chloride to phosphorus ratios? Another way of asking this question is, do you have a false negative rate with these tests?

Finally, could you say a little bit more about pituitary pathology in the MEN 1, which I have always thought is fascinating. The pituitary is usually the least involved, as you mention in your paper, and when it is, it is usually nonfatal; however, what serious pituitary problems can occur in these patients and what corrective actions might you propose as a result of the genetic testing?

Again I would like to thank the Association for letting me comment and I would like to thank Dr. Lairmore for letting me read his manuscript. I invite the membership to read it when it is published. It is nicely written, it is clearly designed, and it will be a classic.

Dr. Richard E. Goldstein (Louisville, Kentucky): I would like to thank Dr. Lairmore for providing me a copy of his paper prior to the meeting and for the privilege of commenting on the work. This is a deceiving body of work, somewhat like an iceberg in that it makes visible only a small amount of what is a very large and laborious project and I want to commend them on this effort. This presentation reports on a prospective program of early gene screening of family members at risk for MEN 1. The paper is very well written, and I would like to take this opportunity to ask Dr. Lairmore a few questions.

Would you comment on the process of gene screening? I think one thing that has held this field back a little bit is this urban myth that seems to be propagated around patients that if they consent to a gene screening and they are found to be positive that they or their family members are somehow denied coverage. At least to my knowledge I don't think this has taken place, and I believe that there is some legislation pending at the federal level to codify that. But would you comment on this?

Moving on to screening, my question is, who should be screened? Fifty seven percent of the patients who were less than 18 and were at risk were positive while only 11% of the patients in the age group between 18 and 30 are at risk. As opposed to MEN 2, where there may not be an upper limit or an upper age at which one stops screening, do you think that there is an upper age at which it is not worth screening patients for this? Putting that into perspective is the fact that I believe that screening costs about a $1000. And that follows a little bit on the Dr. Hanks’ comment.

And lastly, do we know yet based on gene screening whether there are some patients who will have germline features for MEN 1 but will not go on to demonstrate any of the tumors associated with this syndrome?

Dr. Jeffrey A. Norton (Stanford, California): I too enjoyed this presentation very much. I think my concern is the patient whom you describe with a pancreatic tumor and a relatively young age. What operation are you going to do? Would you take out the spleen? What about the duodenum? I think that the problem we face is that these tumors are really multiple both in the duodenum and the pancreas. So I have a concern for the goal of surgery and how you plan to implement it.

Dr. Terry C. Lairmore (St. Louis, Missouri): Dr. Hanks asked about the potential malignancy of these tumors and whether or not the malignant potential can be predicted. No genotype-phenotype correlation has been identified for MEN 1; that is to say that no specific mutations have been shown to carry a higher risk of malignant tumors, so that is not helpful. There has been a prevailing notion for years that there is a relationship between the size of a tumor and its propensity to spread to the regional lymph nodes or the liver. Unfortunately, more recent data, including data by Dr. Doherty and others from Washington University, have shown in our large MEN group that there is really no relationship between the maximum size of the primary tumor and the presence of regional metastases. So that cannot be helpful.

Certain specific tumor types may be more likely to be malignant. About 80% of the gastrinomas are malignant in MEN 1, and the rare islet cell tumors such as the VIPomas and others are more likely to be malignant. Unfortunately, the other tumors can also carry a malignant potential, which is somewhat unpredictable. So I don't think it is easy to predict which tumors will be malignant.

I think the one thing that can be said is that even though a majority of these tumors are either benign or will pursue a rather indolent clinical course, there is clearly a subset of these tumors that can metastasize early to the regional lymph nodes and can be life-limiting. And this can occur in young patients and even patients with small tumors. So I do think we have to be serious about trying to reduce the malignant potential.

Dr. Hanks also asked about the cost of complete screening and also about how we can justify getting additional tests on these patients if they have not disclosed their mutation status. The cost of the screening, which was also asked by Dr. Goldstein, is variable across the country because the test is only available in a few centers. But certainly up to a $1000 is not an unreasonable figure.

All of these patients were tested under a research protocol with the agreement that their information could not be distributed to third parties, including insurers, or made a part of their medical chart. Now, that issue will, of course, become much more significant as this becomes a more routinely used test.

Certainly patients may fear that they can be denied insurability if they have a pre-existing condition or genetic diagnosis. And there are many other ramifications, which include feelings of guilt for passing along the trait, etc. Certain family members may not wish to know information, and that could be compromised by other family members who do want to know. So these issues are complex and certainly beyond the scope of my expertise. But they are significant as indicated by the number of patients we had that declined to pursue their results after they went through the testing.

Dr. Hanks also asked what our false negative rate was, which is an excellent question. He asked how many of the other 49 patients, the genetically negative patients, had an elevated calcium level. Unfortunately, I do not have the data for all 49 of those patients. I can tell you that none of the patients that did have a calcium level drawn had hypercalcemia. But this is an important question that really should be answered. In other words, what is the advantage of a genetic test in terms of its sensitivity and specificity?

Dr. Hanks asked about pituitary disease in MEN 1. These tumors are usually small and benign. They are usually treated medically. In my experience it is very rare for a patient to require surgical intervention. That is usually reserved for tumors that are very large and are creating a mass effect.

Dr. Goldstein asked me to comment on the process of screening and again asked about the issues of privacy of medical information, insurability and informed consent. Again, as I commented, these are quite significant concerns. And I don't think I have all of the answers for that. It is certainly possible that if a patient receives a genetic diagnosis that does make its way into the chart, there is a possibility of an affect on their ability to receive insurance.

Who should be screened? As I pointed out, the most fruitful screening is really in the patients that are under 30 years of age. That is because as the patient gets older and is clinically negative, they are less likely to have a positive genetic test. That is why out of screening 56 people only 7 were genetically positive. The data was skewed because older patients are more likely to have their affected status defined.

And finally, to address Dr. Norton's question—and I think he, as always, really brings us down to practicality. He asked what operation should we do in this 15-year-old patient who has an enhancing lesion in the tail of the pancreas. As I said, I think we ought to do an operation that relieves the patient of their potential malignant risk with the minimal operation that it is possible to do, an operation that preserves pancreatic function, and also with the view these patients may require multiple additional operations over the years. And certainly a laparoscopic approach to this islet cell tumor could be performed including a splenic-reserving enucleation or distal pancreatectomy. In terms of opening the duodenum, if the patient doesn't have hypergastrinemia I don't think that would be necessary. But I know that Dr. Norton's question is whether or not we need to be evaluating the entire pancreas with intraoperative ultrasound and palpation if we are really going to extirpate all of the potentially malignant tumors. And I think these issues remain controversial.

The final comment I would make is that there are many groups, including a group in Sweden now, that has advocated actually for many years removing all visible tumors at a young age, even when the patients only have biochemically positive markers. And the view here is to set the clock back such that they don't have the malignant risk that develops as the tumors increase in size.

Footnotes

Supported by American Cancer Society Grant RPG-99-183-01-CCE, Washington University GCRC grant M01 RR00036, and a Washington University Cancer Center Research Development Award.

Reprints: Terry C. Lairmore, MD, Washington University School of Medicine, Department of Surgery, Section of Endocrine and Oncologic Surgery, Box 8109, 660 S. Euclid Avenue, St. Louis, Missouri. E-mail: lairmoret@wustl.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marx S, Spiegel AM, Skarulis MC, et al. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: Clinical and genetic topics. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:484–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballard HS, Frame B, Hartsock RJ. Familial multiple endocrine adenoma-peptic ulcer complex. Medicine. 1964;43:481–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilkinson S, Teh BT, Davey KR, et al. Cause of death in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Arch Surg. 1993;128:683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doherty GM, Olson JA, Frisella MM, et al. Lethality of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. World J Surg. 1997;22:581–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandrasekharappa SC, Guru SC, Manickamp P, et al. Positional cloning of the gene for multiple endocrine neoplasia-type 1. Science. 1997;276:404–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guru SC, Goldsmith PK, Burns AL, et al. Menin, the product of the MEN1 gene, is a nuclear protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1630–1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agarwal SK, Guru SC, Heppner C, et al. Menin interacts with the AP1 transcription factor JunD and represses JunD-activated transcription. Cell. 1999;96:143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gobl AE, Berg M, Lopez-Egido JR, et al. Menin represses JunD-activated transcription by a histone deacetylase-dependent mechanism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1447:51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lemmens I, Van de Ven WJM, Kas K, et al. Identification of the multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:1177–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bassett JHD, Forbes SA, Pannett AAJ, et al. Characterization of mutations in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:232–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agarwal SK, Kester MB, Debelenko LV, et al. Germline mutations in the MEN1 gene in familial multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and related states. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:1169–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayr B, Apenberg S, Rothamel T, et al. Menin mutations in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia. Eur J Endocrinol. 1997;137:684–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mutch MG, Dilley WG, Sanjurjo F, et al. Germline mutations in the multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 gene: evidence for frequent splicing defects. Hum Mutat. 1999;13:175–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schussheim DH, Skarulis MC, Agarwal SK, et al. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: new clinical and basic findings. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2001;12:173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friesen SR, Kimmel JR, Tomita T. Pancreatic polypeptide as screening marker for pancreatic polypeptide apudomas in multiple endocrinopathies. Am J Surg. 1980;139:61–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mutch MG, Frisella MM, DeBenedetti MK, et al. Pancreatic polypeptide is a useful plasma marker for radiographically evident pancreatic islet cell tumors in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Surgery. 1997;122:1012–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lairmore TC, Chen VY, DeBenedetti MK, et al. Duodenopancreatic resections in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Ann Surg. 2000;231:909–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowney JK, Frisella MM, Lairmore TC, et al. Pancreatic islet cell tumor metastases in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: correlation with primary tumor size. Surgery. 1998;124:1043–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eriksson B, Arnberg H, Lindgren P-G, et al. Neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors: clinical presentation, biochemical and histopathologic findings in 84 patients. J Intern Med. 1990;228:103–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skogseid B, Eriksson B, Lundqvist G, et al. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. A 10year prospective screening study in four kindreds. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991;73:281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wells SAJr, Farndon JR, Dale JK, et al. Long-term evaluation of patients with primary parathyroid hyperplasia managed by total parathyroidectomy and heterotopic autotransplantation. Ann Surg. 1980;192:451–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rizzoli R, Green J III, Marx SJ. Primary hyperparathyroidism in familial multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Long-term follow-up of serum calcium levels after parathyroidectomy. American Journal of Medicine. 1985;78:468–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hellman P, Skogseid B, Oberg K, et al. Primary and reoperative parathyroid operations in hyperparathyroidism of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Surgery. 1998;124:993–999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elaraj DM, Skarulis MC, Libutti SK, et al. Results of operation for hyperparathyroidism in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Surgery. 2003;134:858–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]