Abstract

Objective:

To determine the effects of hypoxia-induced ribonucleotide reductase (RR) production on herpes oncolytic viral therapy.

Summary Background Data:

Hypoxia is a common tumor condition correlated with therapeutic resistance and metastases. Attenuated viruses offer a unique cancer treatment by specifically infecting and lysing tumor cells. G207 is an oncolytic herpes virus deficient in RR, a rate-limiting enzyme for viral replication.

Methods:

A multimerized hypoxia-responsive enhancer was constructed (10xHRE) and functionally tested by luciferase assay. 10xHRE was cloned upstream of UL39, the gene encoding the large subunit of RR (10xHRE-UL39). CT26 murine colorectal cancer cells were transfected with 10xHRE-UL39, incubated in hypoxia (1% O2) or normoxia (21% O2), and infected with G207 for cytotoxicity assays. CT26 liver metastases, with or without 10xHRE-UL39, were created in syngeneic Balb/C mice (n = 40). Livers were treated with G207 or saline. Tumors were assessed and stained immunohistochemically for G207.

Results:

10xHRE increased luciferase expression 33-fold in hypoxia versus controls (P < 0.001). In normoxia, 10xHRE-UL39 transfection did not improve G207 cytotoxicity. In hypoxia, G207 cytotoxicity increased 87% with 10xHRE-UL39 transfection versus nontransfected cells (P < 0.001). CT26 were resistant to G207 alone. Combining 10xHRE-UL39 with G207 resulted in a 66% decrease in tumor weights (P < 0.0001) and a 65% reduction in tumor nodules (P < 0.0001) versus G207 monotherapy. 10xHRE-UL39-transfected tumors demonstrated greater viral staining.

Conclusions:

Hypoxia-driven RR production significantly enhances viral cytotoxicity in vitro and reduces tumor burden in vivo. G207 combined with RR under hypoxic control is a promising treatment for colorectal cancer, which would otherwise be resistant to oncolytic herpes virus alone.

In this study, tumor hypoxia is exploited to enhance herpes viral killing of cancer. A hypoxia-responsive enhancer is used to up-regulate expression of ribonucleotide reductase, an enzyme necessary for viral replication and cytotoxicity. Hypoxia-induced ribonucleotide reductase production in colorectal cancer metastases significantly improved viral oncolysis and reduced tumor burden.

Hypoxia, a reduction in normal tissue oxygen levels, is a common condition of solid tumors. Rapidly proliferating tumors outstrip their vascular supply resulting in hypoxic regions. These areas are reported to have oxygen concentrations less than 2%.1 Oxygen-deficient cancer cells exhibit an increased rate of genetic mutation, local invasion, and metastatic spread.2,3 Similarly, low tumor oxygen tension has been correlated with increased metastases and poor survival in various cancers.4 In addition to the aggressive nature of these tumors, hypoxia confers resistance to standard radiation therapy and chemotherapy.5,6 Hypoxic tumors are thus associated with a poor outcome regardless of treatment modality.3 The development of new therapeutic strategies is necessary. Lower tumor oxygen levels compared with surrounding normal tissues may be used to selectively target cancer cells in gene therapy.7

Hypoxia is a potent signal that induces the production of proteins, which allow cells to adapt to a low oxygen environment. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) is a key transcriptional regulator controlling the expression of diverse hypoxia-inducible genes related to angiogenesis, oxygen transport, cellular adhesion, and glycolysis.8–10 Although involved in adaptive physiologic processes, HIF-1 is also overexpressed in diverse cancers and is associated with tumor progression and metastases.11,12 HIF-1 consists of an oxygen-regulated α subunit (HIF-1α) and a constitutive β subunit (HIF-1β). In hypoxia, HIF-1α translocates to the nucleus where it dimerizes with HIF-1β. This heterodimer binds to the hypoxia-responsive element (HRE) of target genes to stimulate transcription.13 The HRE consensus sequence has been characterized in the 5′ untranslated region of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) gene.14

Replication-competent, multimutated herpes simplex viruses (HSV) have been successful in the treatment of a broad spectrum of malignancies in animal models, including brain, hepatic, gastric, prostate, head and neck, pancreatic, and colorectal.15–20 Genetically engineered oncolytic viruses have been attenuated to have reduced toxicity to normal tissues, while maintaining their inherent ability to kill tumor cells. G207 is a second-generation HSV type-1, containing multiple mutations, which significantly minimize reversion to a pathogenic phenotype. G207 has deletions in both copies of the neurovirulence gene γ134.5, which is responsible for viral spread and replication within the central nervous system. This virus also contains an insertional inactivation of UL39, the gene encoding the large subunit of ribonucleotide reductase (RR).16

RR is the main rate-limiting enzyme for viral DNA synthesis and replication, controlling the nucleotide substrate pool by regulating the conversion of ribonucleotides to deoxyribonucleotides.21 Viral mutants with a defective UL39 gene exclusively replicate in and lyse rapidly dividing cancer cells, which provide sufficient levels of RR.22 Increasing tumor RR levels may potentially enhance viral replication and tumor cell lysis.

This study sets out to determine whether replacement of UL39 under control of a hypoxia-responsive enhancer would promote more vigorous killing of cancer cells by an oncolytic herpes virus and increase tumor specificity through hypoxia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture and Hypoxic Treatment

CT26, a murine colorectal carcinoma cell line syngeneic in Balb/C mice, were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA), maintained in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator at 37°C, and subcultured twice a week. Cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 5 mmol/L nonessential amino acids.

Hypoxic conditions were created by displacement of oxygen with nitrogen in a triple-gas incubator (NuAire, Plymouth, MN). Oxygen concentrations of 1% could be reached and maintained. After plating and transfection procedures, cells were routinely incubated for 12 hours in 21% O2 to allow for attachment and stabilization prior to hypoxic exposure.

HIF-1α Expression

CT26 cells were plated at 5 × 106 cells/dish in 100 mm culture dishes (Costar, Corning Inc., Corning, NY) and incubated in either normoxia (21% O2) or hypoxia (1% O2). After a 24-hour incubation, nuclear extracts were collected for HIF-1α levels (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA). Protein content of nuclear extracts was determined according to the Bradford method (BioRad Protein Assay Reagent, Hercules, CA) by measuring absorbance at 595 nm (Beckman DU 640 spectrophotometer, Fullerton, CA). HIF-1α enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was performed (Active Motif) on 20 μg of nuclear protein from each sample.

Construction of Hypoxia-Responsive Enhancer

Complementary 41 base pair oligonucleotides were constructed encoding the HIF-1 recognition sequence of the human VEGF gene (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). These monomeric HRE were designed with XhoI and SalI compatible ends for multimerization and cloning. The complementary sequences were: (5′-TCGAGCCACAGTGCATACGTGGGCTCCAACAGGTCCTCTTG-3′) and (5′-TCGACAAGAGGACCTGTTGGAGCCCACGTATGCACTGTGGC-3′).23 Paired oligomers were annealed and the 5′ ends of the double-stranded HRE product were phosphorylated with T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs [NEB], Beverly, MA) for subsequent multimerization. Ten copies of the HRE fragment were tandemly ligated with Quick Ligase (NEB). The resulting 10xHRE enhancer was confirmed with sequence analysis and restriction digests.

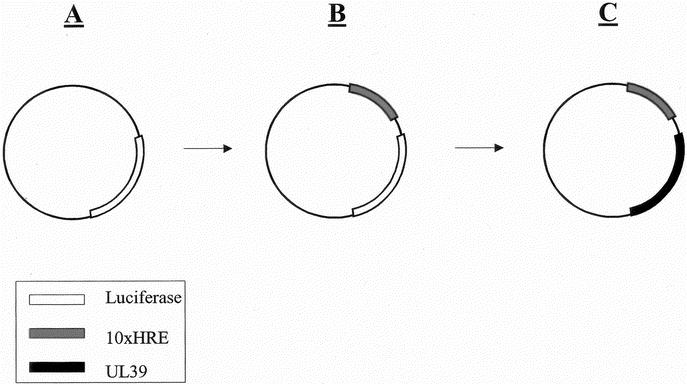

Enhancer Function

We cloned the 10xHRE enhancer into the XhoI site of the pGL3 promoter vector (Promega, Madison, WI) upstream of the minimal SV40 promoter, forming the luciferase reporter plasmid 10xHRE-pGL3 (Fig. 1A, B). CT26 cells were plated at 1.5 × 106 cells/well in 6-well flat-bottom plates (Costar, Corning Inc.). Cells were transfected with 1.6 μg of 10xHRE-pGL3 plasmid using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The native pGL3 plasmid was used as a control in these experiments. Cells were incubated in either 21% O2 or 1% O2 for 18 hours. Cell lysates were collected and a luciferase assay (Luciferase Assay Kit, Promega) was performed using a single injection luminometer (Berthold Technologies MicroLumat Plus, Oak Ridge, TN). Protein concentrations of cell lysates were determined by Bradford's method (BioRad) to normalize luciferase activity between transfected groups.

FIGURE 1. Constructing a vector with an intact UL39 gene under hypoxic control. A, The pGL3 promoter vector (Promega, Madison, WI) with its native luciferase reporter gene. B, Cloning the hypoxia responsive enhancer (10xHRE) into the XhoI restriction site of pGL3. C, The luciferase gene was removed with HindIII and XbaI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) and replaced with the UL39 gene to form 10xHRE-UL39.

Construction of Vector Expressing Ribonucleotide Reductase

A plasmid containing the intact UL39 gene was the kind gift of Medigene Inc. (San Diego, CA). The translated UL39 sequence was PCR amplified using Herculase Hotstart polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) with forward (5′-GCATAGCTGAAGCTTCTGTTGAAATGGCCAGCCG-3′) and reverse (5′- TCCACGTATCTAGAATCTGGATCGCCAGGTCCG-3′) primers (Invitrogen). These primers introduced a unique upstream HindIII restriction site, as well as a unique downstream XbaI site, while excluding the native UL39 promoter and poly-A tail. 10xHRE-pGL3 was digested with HindIII and XbaI (NEB) to remove the luciferase gene. The intact UL39 gene was then ligated between the HindIII and XbaI sites (Quick Ligase, NEB), forming the 10xHRE-UL39 plasmid (Fig. 1C). The sequence was confirmed by PCR screen and restriction digests.

G207 Virus

G207, a generous gift from Medigene Inc., is a multimutated HSV derived from the laboratory wild-type F strain. G207 contains deletions in both copies of the γ134.5 neurovirulence gene. The UL39 gene is also inactivated with an insertional mutation of a functional lacZ gene.16 This insertion serves a reporter function as well as an additional protective mechanism.

In Vitro Cytotoxicity of G207

CT26 cells were plated in 6-well plates and transfected with 1.8 μg of 10xHRE-UL39 plasmid using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Control cells underwent mock transfection. After a 12-hour incubation in normoxia, cells were incubated in either 21% O2 or 1% O2. Twenty-four hours later, cells were infected with G207 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI: number of viral plaque-forming units per tumor cell) of 1 and replaced in the appropriate 21% O2 or 1% O2 incubator.

After viral infection, G207 cytotoxicity was determined by measuring the release of cytoplasmic lactate dehydrogenase from surviving cells over 10 days. Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed with 1.5% TritonX-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Lactate dehydrogenase was quantified with a Cytotox 96 nonradioactive cytotoxicity assay (Promega), measuring the conversion of a tetrazolium salt into a red formazan product. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm with a microplate reader (EL312e, Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT). Cytotoxicity is expressed as the percentage of lactate dehydrogenase activity in treated cells relative to mock-infected cells. All samples were tested in triplicate.

Establishment and Treatment of Hepatic Metastases

All animal procedures were performed with the approval of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Eight-week-old male Balb/C mice were obtained (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA). Animals were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of ketamine and xylazine (100 mg/kg ketamine, 10 mg/kg xylazine) for all procedures.

CT26 cells were plated in 6-well plates and transfected with 1.8 μg of 10xHRE-UL39. Control cells underwent mock transfection. After a 12-hour incubation at 21% O2, cells were harvested, counted, and resuspended (6 × 104 cells/50 μL). Intrahepatic metastases were generated through splenic tumor injection and portal venous delivery.24 A small left subcostal incision was made and the lower pole of the spleen was exteriorized for subcapsular injection. Animals consistently develop between 150 and 300 tumor nodules in the liver by 2 weeks. Mice received splenic injection in 50 μL of PBS through a 30-gauge needle, with either 6 × 104 CT26 cells transfected with 10xHRE-UL39 (n = 20) or 6 × 104 CT26 cells that had undergone mock transfection (n = 20).

The incisions were closed and then reopened 24 hours later for viral infection, through splenic injection as described. In each of the tumor-inoculated groups, mice were randomized to receive either 5 × 104 PFU of G207 in 50 μL of PBS (n = 10) or 50 μL of PBS alone (n = 10). Animals were observed and weighed regularly for 2 weeks, at which time they were killed by CO2 inhalation. Livers were harvested, weighed, and 2 independent investigators counted liver nodules. Four 10-week-old naive Balb/C mice underwent necropsy and hepatectomy to determine normal liver weight.

Immunohistochemistry

Harvested livers were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated in graduated alcohol washes, and embedded in paraffin blocks; 8-μm sections were cut and stained with a rabbit anti-HSV-1 polyclonal antibody (Ready-to-Use, Biogenex, San Ramon, CA). A biotinylated secondary antibody was added and visualized with streptavidin-labeled horseradish peroxidase and chromogen solutions (Super Sensitive Ready-to-Use Detection System, Biogenex). Counterstaining with Harris hematoxylin was performed. Tissues harvested from uninfected animals were used as negative controls. Slides were dehydrated and coverslipped with Permount mounting medium (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). A pathologist reviewed all slides.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Comparisons between groups were performed with a 2-tailed Student t test.

RESULTS

HIF-1α Expression

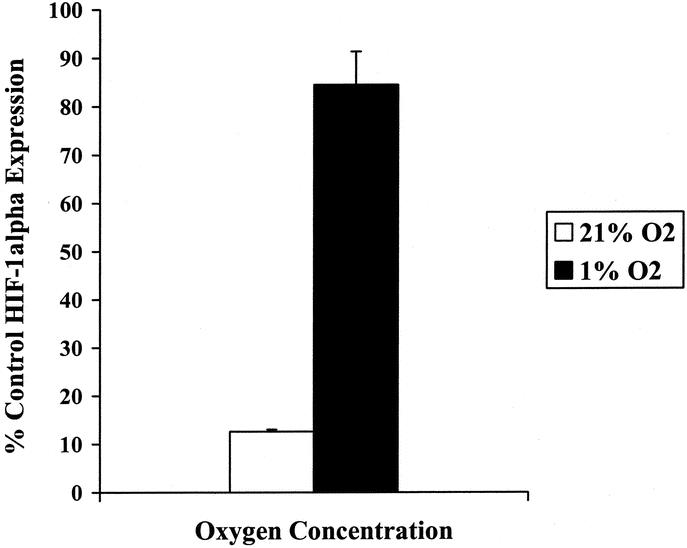

CT26 cells incubated at 21% O2 or 1% O2 were examined for HIF-1α expression by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Following a 24-hour incubation, hypoxic CT26 cells demonstrated a 6.6-fold increase in HIF-1α expression compared with normoxic cells (P < 0.01, Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) by CT26 murine colorectal carcinoma cells in normoxia and hypoxia. CT26 cells were incubated in either 21% O2 or 1% O2 for 24 hours. HIF-1α enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was performed (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) on 20 μg of nuclear protein from each sample. There was a 6.6-fold increase in HIF-1α expression in 1% O2 compared with 21% O2 (P < 0.01).

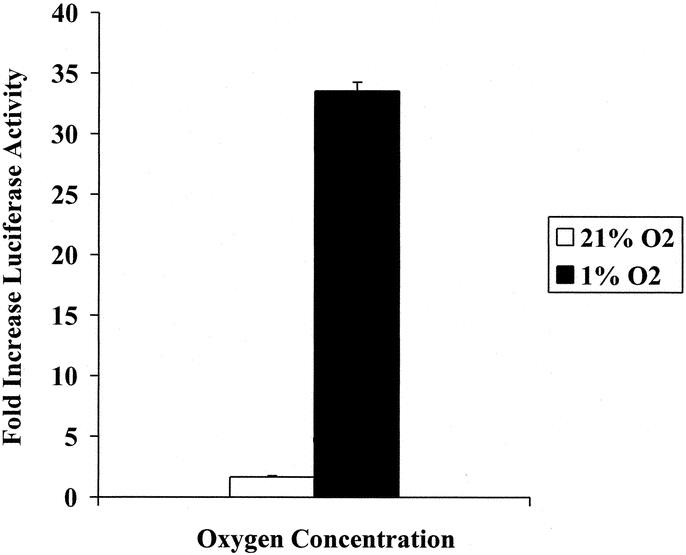

Luciferase Activity

10xHRE enhancer function was assessed by luciferase reporter assay. Following incubation in 21% O2 or 1% O2, CT26 cell lysates underwent analysis for luciferase expression. In 1% O2, CT26 cells transfected with 10xHRE-pGL3 yielded a 33-fold increase in luciferase activity versus cells transfected with pGL3 alone (P < 0.001, Fig. 3). In 21% O2, 10xHRE-pGL3 transfection resulted in a 1.6-fold increase in luciferase activity compared with pGL3 (P < 0.001, Fig. 3). These experiments demonstrate that the 10xHRE enhancer significantly improved paired gene expression in hypoxia, with good specificity in an oxygen-deprived environment.

FIGURE 3. 10xHRE enhancer function assessed by luciferase activity. CT26 murine colorectal cancer cells were transfected with 1.6 μg of our 10xHRE-pGL3 construct or the native pGL3 reporter vector (Promega, Madison, WI). Cells were subsequently incubated in either 21% O2 or 1% O2 for 18 hours, and luciferase assay was performed. Data are expressed in terms of fold increase in luciferase activity compared with pGL3 plasmid transfection alone. 10xHRE-pGL3 transfection resulted in a 33-fold increase in luciferase activity in 1% O2 (P < 0.001). Expression in 21% O2 increased 1.6-fold (P < 0.001).

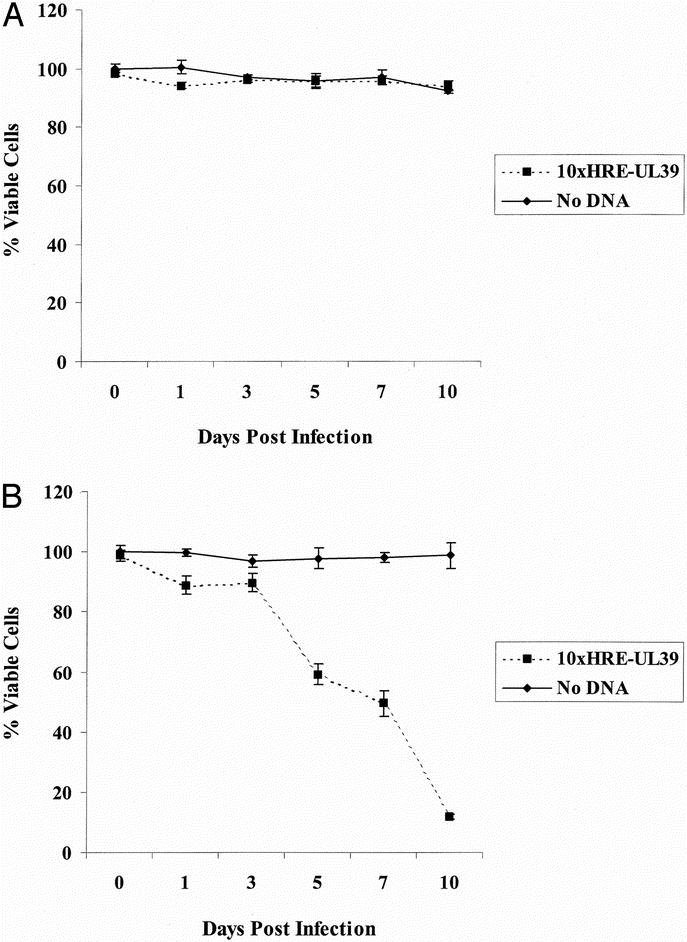

In Vitro Cytotoxicity of G207

CT26 cell viability was measured by cytotoxicity assay to determine viral oncolysis following 10xHRE-UL39 transfection. In 21% O2, 10xHRE-UL39 transfection did not result in improved G207 cell kill compared with mock transfection. Both 10xHRE-UL39 and mock-transfected cells demonstrated resistance to G207 therapy at an MOI of 1, with less than 10% cell kill by day 10. There was no significant difference in cytotoxicities between these 2 groups (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4. G207 cytotoxicity in CT26 murine colorectal cancer cells. A, CT26 cells demonstrated resistance to G207 in normoxia (21% O2) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI: viral plaque-forming unit to tumor cell ratio) of 1. Our 10xHRE-UL39 construct failed to improve cell kill in normoxia. B, CT26 cells were resistant to G207 at an MOI of 1 in hypoxia (1% O2). Transfecting our 10xHRE-UL39 plasmid significantly increased G207 cytotoxicity by day 5, with nearly complete cell death by day 10 (P < 0.001).

When incubated at 1% O2, CT26 cells transfected with 10xHRE-UL39 were more susceptible to G207 oncolysis compared with mock-transfected cells. Twenty-four hours after G207 infection, there was an 11% increase in cytotoxicity with 10xHRE-UL39 transfection, which was statistically significant (P < 0.05). This increase in G207 cytotoxicity improved to 39% by day 5 (P < 0.001) and to 50% by day 7 after infection (P < 0.001). At the completion of 10 days, hypoxic CT26 cells transfected with 10xHRE-UL39 had 87% greater G207 cell kill than mock-transfected cells (P < 0.001, Fig. 4B). Hypoxic CT26 cells that underwent mock transfection were resistant to G207 oncolysis, with no evidence of cytotoxicity 10 days after infection. Furthermore, there was an 88% improvement in G207 cytotoxicity when comparing hypoxic CT26 cells transfected with 10xHRE-UL39 to similarly transfected normoxic CT26 cells (P < 0.001). These results demonstrate that 10xHRE-driven expression of RR can specifically and significantly improve G207 cell kill in hypoxia.

Inhibition of Tumor Growth

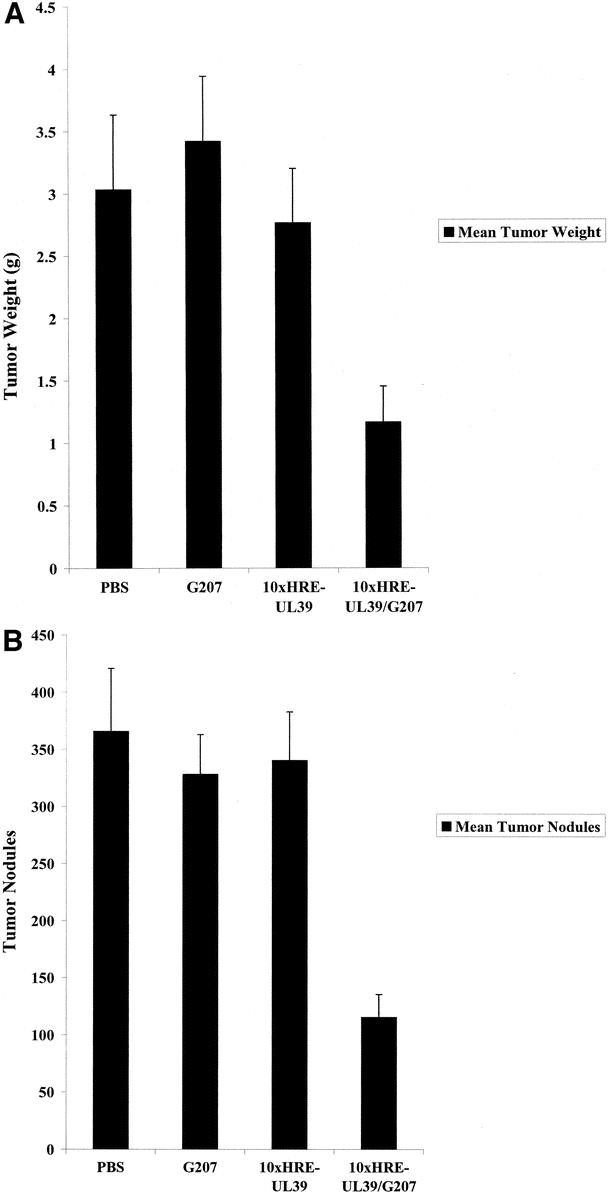

CT26 cells transfected with 10xHRE-UL39 or no DNA were injected into the spleens of Balb/C mice to create an in vivo liver metastases model. Naive Balb/C mice had a mean liver weight of 1.58 ± 0.13 g (n = 4), which was the normal liver weight used in these experiments. Tumor weights were determined by subtracting the normal liver weight from the mean liver weights. Balb/C livers implanted with mock-transfected CT26 tumors had a mean tumor weight of 3.04 ± 0.60 g when treated with PBS and 3.43 ± 0.52 g when treated with G207, which were not significantly different. PBS-treated tumors that had undergone mock transfection or 10xHRE-UL39 transfection also demonstrated no significant difference in weight. However, combining 10xHRE-UL39 transfection with G207 therapy resulted in a mean tumor weight of 1.17 ± 0.28 g, which represented a 66% decrease compared with mock-transfected tumors receiving G207 (P < 0.0001, Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5. Treatment of murine liver metastases with G207 and 10xHRE-UL39 (n = 10 per group). Balb/C mice underwent splenic injection with 6 × 104 CT26 murine colorectal cancer cells transfected with our 10xHRE-UL39 construct or no DNA. Mice were reinjected 24 hours later with either 5 × 104 plaque-forming units of G207 or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Liver tumor burdens were assessed 14 days later. A, There was a 66% decrease in tumor weight (P < 0.0001) with the combination of 10xHRE-UL39 and G207. There was no significant difference among tumor weights when given monotherapy with PBS, 10xHRE-UL39, or G207. B, There was a 65% reduction in tumor nodules (P < 0.0001) when both 10xHRE-UL39 and G207 were given. There was no significant difference among nodule counts when mice received monotherapy with PBS, 10xHRE-UL39, or G207.

Mock-transfected CT26 tumors treated with G207 had an average of 329 ± 34 nodules, which was not significantly different from PBS-treated livers (366 ± 54 nodules). Livers treated with both 10xHRE-UL39 transfection and G207 infection had a mean of 116 ± 20 nodules, which represented a 65% decrease in nodule counts compared with mock-transfected tumors receiving the same dose of G207 (P < 0.0001, Fig. 5B). CT26 liver tumors were resistant to G207 monotherapy, as it was no more efficacious at decreasing tumor weights or nodule counts than PBS (Fig. 5). Furthermore, there was no reduction in tumor weights or nodules with 10xHRE-UL39 transfection alone (Fig. 5). These results demonstrate in vivo efficacy of 10xHRE-UL39 transfection in combination with G207 viral therapy for the treatment of CT26 liver metastases.

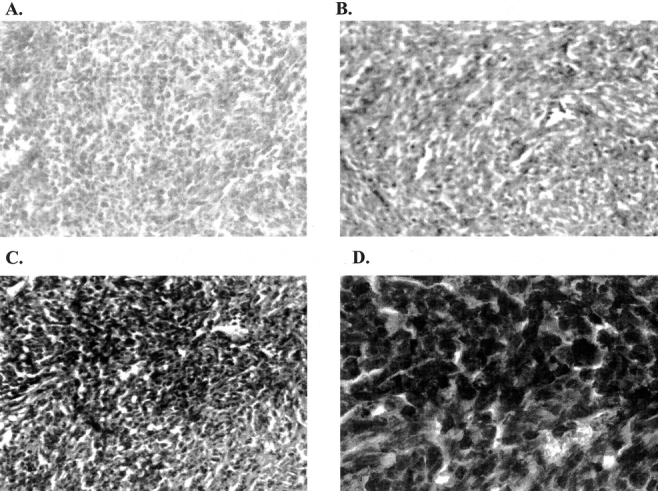

Immunohistochemical Analysis of G207 Infection

Balb/C livers from each group were fixed, sectioned, and then stained for HSV-1 envelope proteins. Mice that were not treated with G207 demonstrated negative HSV staining in all tumor-bearing and normal liver regions (Fig. 6A). In mice treated with G207, tumor-bearing regions stained positively for HSV (Fig. 6B–D), while non–tumor-bearing regions did not stain for HSV. There was appreciably stronger staining for HSV in 10xHRE-UL39-transfected tumors treated with G207 versus mock-transfected tumors treated with G207 (Fig. 6B, C). These results demonstrate enhanced viral infection with 10xHRE-UL39 and G207 combination therapy.

FIGURE 6. Detection of herpes simplex virus (HSV) by immunohistochemistry of Balb/C livers with metastatic CT26 murine colorectal cancer. Fixed tissues were sectioned, stained with a rabbit anti-HSV-1 polyclonal antibody, and examined under light microscopy. The presence of brown represents positive staining for HSV envelope proteins. There was appreciably stronger staining for HSV in 10xHRE-UL39-transfected tumors treated with G207 versus mock-transfected tumors receiving G207. Viral staining was confined to the tumorigenic regions of livers. A, Untreated liver metastases (original magnification ×10). B, G207-treated, mock-transfected liver metastases (original magnification ×10). C, G207-treated, 10xHRE-UL39-transfected liver metastases (original magnification ×10). D, G207-treated, 10xHRE-UL39-transfected liver metastases (original magnification ×60).

DISCUSSION

Since its development in 1995, the replication-competent herpes virus G207 has moved from the laboratory into clinical trials.16,25 Although G207 was initially developed as a brain tumor therapy, animal experiments have demonstrated its efficacy across a wide array of solid tumors.17–19 G207 contains multiple genomic mutations, preventing reversion to a pathogenic phenotype and undesired viral infection. Deletions in both copies of the neurovirulence gene γ134.5 prevent central nervous system spread. There is also a temperature-sensitive mutation in the immediate-early α4 gene, which inhibits viral replication at temperatures greater than 39.5°C in the febrile host. Although the γ134.5 and α4 mutations provide substantial safety features, it is the inactivating mutation of UL39, the gene encoding the large subunit of RR, which makes G207 complementary to tumor cells. G207 can only replicate in rapidly dividing cancer cells, which provide sufficiently high levels of exogenous RR.16

RR consists of 2 nonidentical proteins: the larger subunit R1 and the smaller subunit R2. The rate of cellular DNA synthesis is strongly correlated with RR activity, with the large RR subunit constitutively expressed in dividing cells.26 This primitive enzyme is found in all prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, originating before the divergence of animals from fungi. There is therefore a high degree of conservation between the RR of viruses, animals, and plants.27 Virus can use RR produced by rapidly dividing tumor cells for its own replication. A recombinant HSV lacking UL39 has been shown to preferentially infect liver metastases with elevated RR levels rather than surrounding normal tissue.28 However, hypoxia limits cellular proliferation by inhibiting the cell cycle prior to S-phase.29 This reduced cellular division at low oxygen tensions may hinder viral replication within hypoxic tumors.

Solid tumors become hypoxic as they proliferate and outstrip their blood supply, decreasing the efficacy of standard therapies and promoting malignant progression. Radiation therapy requires free radicals from oxygen to destroy target cells, while altered blood vessel architecture and reduced tumor cell proliferation may promote chemotherapeutic resistance.30,31 Tumor hypoxia has been positively correlated with recurrence in cervical cancer and metastatic spread in soft tissue sarcoma when tumor pO2 is less than 10 mm Hg.3,32 Reports reveal that the median oxygen concentration for head and neck, cervical, and breast cancers is 1% to 4%, with most tumors having more hypoxic regions.4,33,34 We therefore used 1% O2 to represent tumor hypoxia in our in vitro experiments, to mimic the physiology of solid tumors. Hypoxia has been further demonstrated in various tumor types, including prostate, brain, colorectal, pancreatic, gastric, ovarian, lung, renal, and melanoma.12,35,36 Since hypoxia is a prevalent solid tumor condition associated with poor prognosis, recent research suggests exploiting it as a means to target and improve cancer therapy.36

In hypoxia, the transcriptional regulator HIF-1 binds to the HRE in the enhancer region of hypoxia-inducible genes to up-regulate gene expression. The HRE within the 5′ flanking region of the VEGF gene and the 3′ flanking region of the erythropoietin (EPO) gene have been well characterized.14,37 We constructed our hypoxia-responsive enhancer from the VEGF HRE sequence, as the EPO HRE has demonstrated low hypoxic inducibility and high baseline activity in normoxia. Moreover, human EPO HRE shows increased paired gene expression only in human cell lines. Although there is considerable homology between mammalian HRE sequences, murine cells have lower inducibility of human VEGF HRE than human cells.38 Our 10xHRE enhancer resulted in a 33-fold increase in luciferase expression when testing human VEGF HRE in a murine cell line. Paired gene transcription may have even been higher if a human cancer cell line were used. Increasing HRE copy number has been shown to greatly improve enhancer function, particularly after 3 copies are multimerized. However, paired gene expression continues to increase in a nonlinear fashion up to 10 HRE copies.7,23,36 We therefore designed our enhancer using 10 repeats of the VEGF HRE to maximize activity in hypoxic murine cancer cells.

In this study, we show that CT26 murine colorectal cancer cells overexpress HIF-1α in response to hypoxia. We have demonstrated good function of our 10xHRE enhancer at 1% O2 and suspect that our enhancer works over a wider range of oxygen concentrations as similar constructs have shown.7 The atmospheric oxygen concentration of 21% was used as the normoxic standard in our experiments, yet the actual oxygen concentration of normal tissues may be lower.34,39 Nevertheless, reports reveal that there is little difference in multimerized HRE enhancer function between 5% O2 and 21% O2.7 Upon pairing this 10xHRE enhancer with an intact UL39 gene in hypoxic CT26 cells, G207 cytotoxicity increased 87%. There was no improvement in normoxia, supporting 10xHRE-UL39 specificity to a low oxygen environment. Combining G207 with a hypoxia-inducible RR-expressing vector showed promising results in vivo, where we reduced Balb/C liver metastases by 65%. However, at the same dose, G207 given alone was ineffective at reducing tumor burden. Balb/C liver immunohistochemistry showed more intense HSV tumor staining in livers treated with both 10xHRE-UL39 and G207, compared with G207 alone. This staining pattern suggests improved G207 replication in tumors transfected with 10xHRE-UL39. Normal liver parenchyma did not stain positively for HSV, providing evidence for preserved G207 tumor specificity despite potentially high local levels of RR. These results reveal that transfection of UL39 under 10xHRE control confers improved G207 tumor cytotoxicity in murine colorectal cancer cells.

Retained tumor specificity and enhanced oncolytic activity support the construction of a recombinant G207 containing hypoxia-targeted RR expression. The UL39 gene has been inactivated in G207 by a lacZ insertional mutation. We plan to reintroduce a functional UL39 gene under control of our 10xHRE enhancer through homologous recombination with purified G207 DNA. Creating this recombinant virus would circumvent the transfection process and the possibility of unstable gene expression. Recombinant G207 autonomously expressing 10xHRE-UL39 may ultimately be used as definitive therapy for established tumors. Our current experimental results are a proof of principle that reintroducing UL39 into G207 under hypoxic control can improve viral efficacy without compromising tumor specificity or safety. We show that hypoxia, a negative tumor characteristic, can be exploited as a means of improving oncolytic viral therapy in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Guo-jie Ye, PhD, for his guidance with cloning procedures, and Medigene, Inc. (San Diego, CA) for providing us with G207 virus and plasmid DNA containing UL39.

Discussions

Dr. B. Mark Evers (Galveston, Texas): I want to congratulate Drs. Reinblatt and Fong on another outstanding paper describing the use of oncolytic viral therapy as potential treatment for colorectal metastases.

Viral oncolysis represents a unique strategy to exploit the natural process of viral replication to kill tumor cells. Although this concept dates back nearly a century, recent advances in the fields of molecular biology and virology have enabled investigators to genetically engineer viruses with greater potency and tumor specificity.

This current report by Dr. Fong's group takes advantage of tumor hypoxia to engineer a potential therapy to enhance the effects of the oncolytic herpes simplex virus G207, which has been genetically engineered to exhibit reduced virulence for noncancerous cells by deletion of ribonucleotide reductase, which is a key enzyme in viral DNA synthesis. The mammalian ribonucleotide reductase is elevated in tumor cells relative to normal cells. Therefore, herpes simplex virus mutants defective in ribonucleotide reductase replicate preferentially in tumor cells.

The authors have constructed a plasmid that introduces the ribonucleotide reductase under the control of a hypoxia-responsive promoter into tumor cells. They then demonstrate that, in both in vitro and in vivo models, the combination of the transfection of this hypoxia responsive plasmid along with infection of the herpes simplex virus construct G207 greatly enhances the efficacy of G207 alone in the CT26 murine colorectal cancer, which is normally unresponsive to G207 therapy. This represents a potentially important modification, which may enhance the efficacy of oncolytic viral therapy for numerous cancer types that are characterized by tumor hypoxia. I have 2 questions for Dr. Reinblatt.

This represents an elegant way of enhancing tumor kill by oncolytic viruses. However, I wonder how this particular therapy may be better than other modifications that have been described, including engineering these herpes simplex viruses to express cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-12, which have shown significant anti-tumor activity and the ability to prolong survival in several mouse models. Others have also reported optimizing the potency of these viral vectors by inserting genes that can activate prodrugs that can diffuse to neighboring tumor cells and produce bystander killing. Therefore, this bystander effect could theoretically also kill surrounding hypoxic tumor cells and therefore optimize the efficiency of this system. So could the authors speculate on the advantages of their particular system compared with other mechanisms of optimizing viral therapy?

The second question has to do with how the authors foresee this therapy applied clinically. In this current study, they specifically transfect the colon cancer cells with ribonucleotide reductase gene controlled by the hypoxia-responsive enhancer; therefore, in theory, all of the cells contain this modified gene that would provide great specificity in this system. However, in order to take this to a clinical setting, you would need to reinsert ribonucleotide reductase under the control of the hypoxia-responsive enhancer in the same vector. If this is done, however, one worries that nonspecific effects will occur which would limit the safety of this particular therapy. Although one would hope that the ribonucleotide reductase would only be produced in areas of hypoxia, there is a certain amount of “leakiness” in these systems, which conceivably could mean that normal noncancerous cells could be affected by this particular therapy.

Once again, I greatly appreciate the opportunity to comment on this work and look forward to future innovations by your group.

Dr. Kevin E. Behrns (Chapel Hill, North Carolina): Thank you, Dr. Fong, for an excellent presentation and for providing me with a copy of the manuscript. You and your colleagues should be congratulated on exploiting the differential physiologic function between normal and tumor cells to create a potential therapy that is specific for cancer cells. This work is exciting not only because it takes advantage of tumor cell characteristics but it incorporates gene therapy and it may be used as an adjunct to other therapies such as anti-angiogenic agents.

One of the problems in treating tumor cells is they have marked variability, and certainly the tumor cells will have different degrees of hypoxia and free radical generation. Do you know the hypoxic status of metastatic colorectal cells in situ? Are they hypoxic within a tumor nodule? What percent would you estimate would be responsive to such therapy? Do you think that you would have to use embolization in most of these patients?

Understandably, for experimental purposes you used oxygen concentration of 1% in the in vitro experiments. Did you perform oxygen dose response experiments to see how sensitive they were to hypoxia?

Furthermore, in the in vitro experiments was the response limited to hypoxia or was overexpression of hypoxia inducible factor necessary? And how well does HIF expression correlate with the hypoxia? An alternative way to express this would be: did you perform any experiments in which HIF was inhibited by siRNAs, or other means?

Finally, in the in vivo experiments you transfected the colon cancer cell line with ribonucleotide reductase in vitro and then administered the cells beneath the splenic capsule, which then trafficked to the liver. Other than the strategy that Dr. Fong briefly presented at the end, what other strategies would you have to target RR to the tumor cells?

This represents exciting and novel work, and thank you for sharing it with us.

Dr. W. Roy Smythe (Houston, Texas): I would like to also congratulate Drs. Reinblatt and Fong on a very extensive series of experiments and a very novel approach using the cytolytic technique.

When I was working with HSV in the mid ’90s in the laboratory, we were discouraged by the FDA to use cytolytic herpes simplex viruses due to mainly theoretical concerns, because of cytolysis and also because of potential for latent viral infections. Could the authors comment on the current feeling of the FDA in regards to the clinical use of these cytolytic viruses?

My second question is: it seems that for your particular model the expression of HIF-1α is critical for this to work. Can you comment on the generalizable nature of HIF-1α alpha expression in colon cancer cell lines or preferably tumor specimens?

Lastly, have you looked at the vaccine effect with this vector? In some previous work done with HSV, it has been very interesting that there has been a very significant vaccine effect engendered by the use of the virus. In this scenario, subsequent introductions of tumor cells would lead to much smaller tumor growth, probably because of the increased antigenicity of this virus and its breakdown products over that of adenoviral nonlytic infections.

Dr. William C. Lineaweaver (Jackson, Mississippi): I would like to take this opportunity to apologize to Dr. Fong because I had overlooked my note on his very good question earlier. But this excellent paper lets me bring up the point that he was bringing up.

A large hurdle in using VEGF clinically, for example, in breast reconstruction, is that these operations are done in people who have had breast cancer. As many of you know, VEGF was originally called tumor angiogenesis factor and was associated with vascularization of tumors, perhaps as a response to hypoxia in tumor tissue.

As this extremely interesting principle is brought into in vivo studies, how will you be assaying for the, in effect, neovascularization stimulus of your hypoxia strategies? And will you be looking at ways to block such things as VEGF or other angiogenesis stimulators?

Dr. Max R. Langham, Jr. (Gainesville, Florida): To extend Dr. Lineaweaver's question just a little bit, Dr. Fong (and I must admit this is not an area I have any special expertise in so this may be a bit of a naive question), the downstream effects of the hypoxic responsive promoter with the cytokines certainly should impact BCL-2 and other proteins that are involved in apoptosis and may be involved in metastasis. Thus, I was wondering whether or not you had any information for us about the downstream effects of your promoter with hypoxia as it relates to not the only vascular invasion but also to apoptosis.

Dr. Maura Reinblatt (New York, New York): Previous studies have reported the use of herpes viruses to introduce pro-drugs or cytokines that inhibit tumor growth. Our study differs from past experiments by targeting tumor hypoxia, a typically negative cancer characteristic. Hypoxia is a common condition found in most solid tumors as they outgrow their blood supply. In addition, hypoxia confers a malignant phenotype with increased angiogenesis and metastases, as well as resistance to radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Lower tumor oxygen levels compared to surrounding normal tissues may thus be used to target cancer cells with viral gene therapy.

Viral delivery of genes is one of the most common gene therapy tools used today. Since these viruses preferentially infect cancer cells, hypoxia-induced ribonucleotide reductase expression can be appropriately targeted. Although there are several potential methods to target genes to cancer cells, one of the simplest is through replication-competent herpes viruses such as G207. By introducing our construct into G207, ribonucleotide reductase production can be targeted to the same hypoxic tumor cells that would ultimately be lysed. Our report reveals the potential clinical application of this approach.

Combining our hypoxia-responsive enhancer with the ribonucleotide reductase gene enhances both herpes viral cytotoxicity and specificity in a colorectal cancer metastases model. By constructing a recombinant herpes virus expressing ribonucleotide reductase under hypoxic control, we would circumvent the need for plasmid transfection and may show anti-tumor efficacy with direct tumor injection or regional delivery. This recombinant virus may therefore have broad clinical applicability.

The recombinant virus containing a hypoxia-inducible ribonucleotide reductase gene would infect cancer cells in the same fashion as G207. Similarly, this virus would preferentially replicate in rapidly dividing tumor cells with high ribonucleotide reductase levels. In addition, hypoxic tumor cells that may not be actively dividing will also be infected. These quiescent cells will express ribonucleotide reductase in their low oxygen environment, thus enhancing viral replication and cytotoxicity. Although viral tumor cytotoxicity is increased, viral specificity is maintained.

As an additional safeguard, our hypoxia-responsive enhancer has minimal activity in normal tissues. The enhancer has been shown to function only at oxygen concentrations less than 5%. Physiologic hypoxia is approximately 10% O2, with no region of the body having lower oxygen levels other than tumor cells.

Tumor hypoxia can be artificially enhanced by several methods, including hepatic artery embolization for liver metastases. However, this is not always necessary since most tumors are inherently hypoxic and we would simply exploit this intrinsic characteristic. As solid tumors proliferate, they outstrip their blood supply and become hypoxic. A broad spectrum of tumor types have been reported to be hypoxic, including colorectal cancer. Tumors have median oxygen concentrations between 1% and 2%, with many having areas of hypoxia less than 1% O2.

In these experiments, we used 2 artificial oxygen tensions. We chose 1% O2 to represent hypoxia, as we felt that this oxygen concentration would most closely mimic tumor hypoxia. Tumor cells are accustomed to growing in culture at 21% O2, and this was therefore chosen to represent normoxia. Moreover, the literature suggests that there is little difference in hypoxia-responsive enhancer function between 5% and 21% O2.

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) is overexpressed in hypoxic cells and not in normoxic cells. Although HIF-1 is the key transcriptional regulator of numerous genes necessary for glycolysis, erythropoiesis, and angiogenesis, it is not necessary for their constant baseline level of transcription in normoxia. We have demonstrated HIF-1 overexpression in a wide array of human cancer cell lines in hypoxia, including breast, pancreatic, hepatocellular, and colorectal. We have specifically tested 2 colorectal cancer cell lines, both expressing high HIF-1 levels in hypoxia. Therefore, our hypoxia-responsive enhancer can be used as a gene therapy tool in numerous cancer types.

Noncancerous cells undergo apoptosis in a hypoxic environment. One of the many differences between tumor cells and normal cells is that tumor cells can evade apoptotic cell death and survive in this inhospitable environment. The mechanism for tumor cell survival at low oxygen levels is unclear. Not all tumor cells possess this adaptive capability, but those that do evade apoptosis and thrive.

The safety profile of herpes viral therapy has been well documented. Mineta, Rabkin, and Martuza developed G207 in 1995, and within the past 10 years this virus has gone from the laboratory bench to clinical trials. A phase I clinical trial has recently been completed by the University of Alabama group, comprising 21 patients receiving direct inoculation of G207 into recurrent gliomas resistant to standard therapy. Patients received doses between 1 × 106 and 3 × 109 plaque-forming units without attributable severe side effects or toxicities, doses much higher than those used in our study. Another herpes virus, NV1020, was initially developed as a potential anti-herpetic vaccine. It failed as a vaccine yet was found to have significant oncolytic properties. This virus is currently undergoing clinical trials at our institution.

Footnotes

Supported in part by grants RO1 CA 76416 and RO1 CA/DK80982 (Y.F.) from the National Institutes of Health, grant MBC-99366 (Y.F.) from the American Cancer Society, and grant BC024118 from the U.S. Army.

Reprints: Yuman Fong, MD, Department of Surgery, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Ave, New York, NY. E-mail: Fongy@mskcc.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vaupel P, Kallinowski F, Okunieff P. Blood flow, oxygen and nutrient supply, and metabolic microenvironment of human tumors: a review. Cancer Res. 1989;49:6449–6465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuan J, Narayanan L, Rockwell S, et al. Diminished DNA repair and elevated mutagenesis in mammalian cells exposed to hypoxia and low pH. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4372–4376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hockel M, Schlenger K, Aral B, et al. Association between tumor hypoxia and malignant progression in advanced cancer of the uterine cervix. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4509–4515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brizel DM, Sibley GS, Prosnitz LR, et al. Tumor hypoxia adversely affects the prognosis of carcinoma of the head and neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;38:285–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bush RS, Jenkin RD, Allt WE, et al. Definitive evidence for hypoxic cells influencing cure in cancer therapy. Br J Cancer Suppl. 1978;37:302–306. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tannock I, Guttman P. Response of Chinese hamster ovary cells to anticancer drugs under aerobic and hypoxic conditions. Br J Cancer. 1981;43:245–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shibata T, Giaccia AJ, Brown JM. Development of a hypoxia-responsive vector for tumor-specific gene therapy. Gene Ther. 2000;7:493–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lal A, Peters H, St. Croix B, et al. Transcriptional response to hypoxia in human tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1337–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Semenza GL, Wang GL. A nuclear factor induced by hypoxia via de novo protein synthesis binds to the human erythropoietin gene enhancer at a site required for transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:5447–5454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Semenza GL, Roth PH, Fang HM, et al. Transcriptional regulation of genes encoding glycolytic enzymes by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:23757–23763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zagzag D, Zhong H, Scalzitti JM, et al. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha in brain tumors: association with angiogenesis, invasion, and progression. Cancer. 2000;88:2606–2618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhong H, De Marzo AM, Laughner E, et al. Overexpression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha in common human cancers and their metastases. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5830–5835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang GL, Jiang BH, Rue EA, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5510–5514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg MA, Schneider TJ. Similarities between the oxygen-sensing mechanisms regulating the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and erythropoietin. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4355–4359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walker JR, McGeagh KG, Sundaresan P, et al. Local and systemic therapy of human prostate adenocarcinoma with the conditionally replicating herpes simplex virus vector G207. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:2237–2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mineta T, Rabkin SD, Yazaki T, et al. Attenuated multi-mutated herpes simplex virus-1 for the treatment of malignant gliomas. Nat Med. 1995;1:938–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kooby DA, Carew JF, Halterman MW, et al. Oncolytic viral therapy for human colorectal cancer and liver metastases using a multi-mutated herpes simplex virus type-1 (G207). FASEB J. 1999;13:1325–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carew JF, Kooby DA, Halterman MW, et al. Selective infection and cytolysis of human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma with sparing of normal mucosa by a cytotoxic herpes simplex virus type 1 (G207). Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:1599–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bennett JJ, Delman KA, Burt BM, et al. Comparison of safety, delivery, and efficacy of two oncolytic herpes viruses (G207 and NV1020) for peritoneal cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2002;9:935–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McAuliffe PF, Jarnagin WR, Johnson P, et al. Effective treatment of pancreatic tumors with two multimutated herpes simplex oncolytic viruses. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:580–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thelander L, Reichard P. Reduction of ribonucleotides. Annu Rev Biochem. 1979;48:133–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mineta T, Rabkin SD, Martuza RL. Treatment of malignant gliomas using ganciclovir-hypersensitive, ribonucleotide reductase-deficient herpes simplex viral mutant. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3963–3966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Post DE, Van Meir EG. Generation of bidirectional hypoxia/HIF-responsive expression vectors to target gene expression to hypoxic cells. Gene Ther. 2001;8:1801–1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lafreniere R, Rosenberg SA. A novel approach to the generation and identification of experimental hepatic metastases in a murine model. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1986;76:309–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Markert JM, Medlock MD, Rabkin SD, et al. Conditionally replicating herpes simplex virus mutant, G207 for the treatment of malignant glioma: results of a phase I trial. Gene Ther. 2000;7:867–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mann GJ, Musgrove EA, Fox RM, et al. Ribonucleotide reductase M1 subunit in cellular proliferation, quiescence, and differentiation. Cancer Res. 1988;48:5151–5156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hughes AL. Origin and evolution of viral interleukin-10 and other DNA virus genes with vertebrate homologues. J Mol Evol. 2002;54:90–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carroll NM, Chiocca EA, Takahashi K, et al. Enhancement of gene therapy specificity for diffuse colon carcinoma liver metastases with recombinant herpes simplex virus. Ann Surg. 1996;224:323–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amellem O, Pettersen EO. Cell cycle progression in human cells following re-oxygenation after extreme hypoxia: consequences concerning initiation of DNA synthesis. Cell Prolif. 1993;26:25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gray LH, Conger AD, Ebert M, et al. The concentration of oxygen dissolved in tissues at the time of irradiation as a factor in radiotherapy. Br J Radiol. 1953;26:638–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koukourakis MI, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF1A and HIF2A), angiogenesis, and chemoradiotherapy outcome of squamous cell head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53:1192–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brizel DM, Scully SP, Harrelson JM, et al. Tumor oxygenation predicts for the likelihood of distant metastases in human soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer Res. 1996;56:941–943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hockel M, Knoop C, Schlenger K, et al. Intratumoral pO2 predicts survival in advanced cancer of the uterine cervix. Radiother Oncol. 1993;26:45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dachs GU, Greco O, Tozer GM. Targeting cancer with gene therapy using hypoxia as a stimulus. Methods Mol Med. 2004;90:371–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frederiksen LJ, Siemens DR, Heaton JP, et al. Hypoxia induced resistance to doxorubicin in prostate cancer cells is inhibited by low concentrations of glyceryl trinitrate. J Urol. 2003;170:1003–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruan H, Su H, Hu L, et al. A hypoxia-regulated adeno-associated virus vector for cancer-specific gene therapy. Neoplasia. 2001;3:255–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Semenza GL, Nejfelt MK, Chi SM, et al. Hypoxia-inducible nuclear factors bind to an enhancer element located 3′ to the human erythropoietin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5680–5684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shibata T, Akiyama N, Noda M, et al. Enhancement of gene expression under hypoxic conditions using fragments of the human vascular endothelial growth factor and the erythropoietin genes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;42:913–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hockel M, Schlenger K, Knoop C, et al. Oxygenation of carcinomas of the uterine cervix: evaluation by computerized O2 tension measurements. Cancer Res. 1991;51:6098–6102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]