Abstract

Objetives:

(1) To show that total thyroidectomy (TT) can be performed in multinodular goiter (MG) by surgeons with experience in endocrine surgery with a definitive complication rate of 1% or less; and (2) to analyze the risk factors for complications in these patients.

Summary Background Data:

There is current controversy over the role of TT in the treatment of MG; although there are potential benefits, high rates of complications are not acceptable in surgery for a benign pathology.

Patients and Method:

A prospective study was conducted on 301 MGs meeting the following criteria: (1) bilateral MG; (2) no prior cervical surgery; (3) operation by surgeons with experience in endocrine surgery; (4) no associated parathyroid pathology; (5) no initial thoracic approach; and (6) minimum follow-up of 1 year. Age, sex, time of evolution, symptoms, cervical goiter grade, intrathoracic component, thyroid weight, and presence of associated carcinoma were analyzed as risk factors for complications. The χ2 test and a logistic regression analysis were applied.

Results:

Complications were presented by 62 patients (21%), corresponding to 29 hypoparathyroidisms, 26 recurrent laryngeal nerve injuries, 4 lesions of the superior laryngeal nerve, 3 cervical hematomas, and 1 infection of the cervicotomy. The variables associated with the presence of these complications were hyperthyroidism (P = 0.0033), compressive symptoms (P = 0.0455), intrathoracic component (P = 0.0366), goiter grade (P = 0.0195), and weight of excised specimen (P = 0.0302); hyperthyroidism (relative risk [RR] 2.5) and intrathoracic component (RR 1.5) persisted as independent risk factors. Definitive complications appeared in 3 patients (1%), corresponding to 2 hypoparathyroidisms and 1 recurrent laryngeal nerve injury. Two cases corresponded to a toxic goiter, and the third to an intrathoracic goiter with compressive symptoms.

Conclusion:

In endocrine surgery units, TT can be performed for MG with a definitive complication rate of around 1%; the main independent risk factors for the development of complications are hyperthyroidism and goiter size.

There is current controversy over the role of total thyroidectomy in the treatment of multinodular goiter because high rates of complications are not acceptable. A prospective study was conducted on 301 goiters operated by surgeons with experience in endocrine surgery. The definitive complication rate was 1%, and the main risk factors were hyperthyroidism and goiter size.

Most patients undergoing surgery for multinodular goiter (MG) require bilateral thyroid resection. However, there is currently no consensus on what the most appropriate technique is.1–4 Subtotal thyroidectomy (ST) has been the surgical treatment of choice in surgery for MG, but it does have several inconveniences, among which is a high rate of recurrence (10 to 30%).3 Total thyroidectomy (TT) does not have these disadvantages, but it does involve a higher potential risk of complications. Reported morbidity rates are as high as 3.5% for definitive hypoparathyroidism and 3.1% for permanent recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) injury, to reach 5% and 17%, respectively, when there are recurrent goiters. These figures are unacceptable for the surgical treatment of a benign pathology occurring in a relatively young population.1–14 It has now been seen that with skilled training these complications could be reduced.15 However, there are few prospective studies3–4 to confirm these data.

The risk factors for definitive complications, whether hypoparathyroidism or recurrent lesion, have not been investigated systematically. There are exceptional multivariate analyses that evaluate the influence of risk factors for disease and hospital on the rates of complications of benign thyroid surgery, and those that exist are very heterogeneous with regard to surgical technique and surgeons’ experience.9

The aims of this study are to demonstrate that TT for MG can be performed with a permanent complication rate of 1% or less and to analyze the risk factors for complications with this technique performed in a reference center by surgeons with experience in endocrine surgery.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A prospective study included 301 patients diagnosed and surgically treated for MG between January 1996 and January 2001. The selection criteria were: (1) bilateral MG, defined as that which presents 1 or more nodules in each thyroid lobe on cervical exploration; (2) no prior cervical surgery; (3) no associated parathyroid pathology; and (4) no goiters where the thoracic approach is indicated from the outset.

The patients’ mean age was 48 ± 14 years. Most of them were women (n = 268; 89%), with a mean time of goiter evolution of 90 ± 60 months. Forty-nine percent (n = 146) were asymptomatic, and the most common clinical features in the rest were compressive symptoms (29%; n = 86) followed by hyperparathyroidism (n = 69; 23%). On physical exploration, 15% (n = 45) presented with a grade I goiter (not visible but palpable) and 57% (n = 170) with a grade II goiter (visible and palpable), and the remaining 28% (n = 86) with a grade III goiter (compromising neighboring structures).

All the patients had a complete basic blood test and thyroid hormone study, simple chest radiology, and a thyroid sonography (Diasonics DRF 1000 real-time sonograph). In the 69 cases with hyperparathyroidism, there was an increase in T4 and a decrease in TSH; in the 2 with hypoparathyroidism, there was a decrease in T4 and an increase in TSH. Simple chest radiology was pathologic in 78 patients (26%), with tracheal compression and/or deviation in 45 of them and a mediastinal mass in 61. Sonography informed in all cases of bilateral MG, revealing an intrathoracic component in 70 (23%), a nodule with suspected malignancy in 17 (6%), and cervical adenopathies in 10 (3%). Thyroid gammagraphy was done in the 69 toxic goiters (23%) and in all cases revealed at least one hot nodule. Cervical CT was performed in the 70 goiters (23%) suspected with an intrathoracic component, and all of them revealed a cervicothoracic MG compressing the neighboring structures but without infiltrating them. FNA of the dominant nodule was done in 132 patients (44%) and informed of colloid in 99 cases (75%), follicular proliferation in 22 cases (17%), and suggested malignancy in 7 (5%). Laryngoscopy was performed in the 5 patients with dysphonia (2%) and showed unilateral involvement of the vocal chords (3 left and 2 right) in all of them.

Initially, 142 (47%) patients were controlled with medical treatment: the 2 hypothyroidisms with thyroxin, the 69 toxic goiters with 30 to 40 g/d of methimazole (1 patient required 300 g/d of propylthiouracil due to poor tolerance to the methimazole), and the remaining 71 corresponded to euthyroid goiters that were treated with a suppressive dose of thyroxin. Indications for surgery were suspected malignancy (n = 93; 31%), compressive symptoms (n = 66; 22%), asymptomatic intrathoracic goiter (n = 35; 12%), hyperthyroidism resisting conservative treatment (n = 36; 12%), patient's request (n = 35; 12%), progressive goiter increase (n = 22; 7%), and presence of radiologic tracheal compression (n = 14; 5%).

The operations were performed by 2 surgeons with experience in endocrine surgery (ie, they had previously performed more than 100 thyroid operations12), with TT as the surgical technique. The 2 recurrent nerves, the 2 superior laryngeal nerves, and at least 3 parathyroids were identified in all cases. It was observed in 3 patients (1%) that a parathyroid have been removed with the thyroid. A parathyroid autotransplant at the sternocleidomastoid muscle was performed in this case. In 62 cases (21%) an intrathoracic component was detected in the goiter, according to Eschapase's definition,16 which considers as such a totally or partially localized goiter in the mediastinum, and which in the operative position has a lower edge at least 3 cm below the sternal manubrium.

During the immediate postoperative period, we performed routine determination of calcemia 24 and 48 hours after the thyroidectomy and a laryngoscopy by an otorhinolaryngologist during the first postoperative week. Hypoparathyroidism was considered when the calcium readings were below 7.5 mg/dl or less than 8.5 mg/dl if there were symptoms due to hypocalcemia;14 if the calcemia remained below 8.5 mg/dl at 1 year it was labeled as permanent. RLN injury was considered to be a postsurgical alteration in the tone, timbre, or intensity of the voice, with confirmation of vocal chord alteration by laryngoscopy; it was definitive if it persisted more than 12 months.14 Preoperative dysphonias were not considered a complication unless laryngoscopy informed of contralateral recurrent paralysis with regard to the preoperative situation.

The mean weight of the excised goiter was 90 ± 53 g (50 to 1510 g), and a parathyroid was found in 1 of the excised specimens (0.3%). A lymphocytic thyroiditis was associated in 24 cases (8%), and in 25 goiters (8%) a thyroid carcinoma (20 papillary, 4 follicular and one medullary), 12 of which (48%) were microcarcinomas.

All the patients were reviewed at 1, 3, and 6 months and annually thereafter and were treated with substitutive doses of hormone therapy (L-thyroxin). In the patients with hypoparathyroidism and/or dysphonia, the review was done monthly until the calcemia returned to normal without medication or the dysphonia disappeared. The patients with RLN injury received a laryngoscopic control at 6 months, and at 1 year if involvement of the vocal chord persisted. When patients became normal in either group, they then had the standard follow-up as applied to the rest of the patients without complications.

The variables analyzed to detect risk factors were: (1) age; (2) sex; (3) time of evolution; (4) symptoms; (5) cervical goiter grade; (6) intrathoracic prolongation; (7) duration of surgery; (8) weight of excised specimen; and (9) associated thyroid carcinoma.

For the statistical analysis, we used contingency tables with the χ2 test complemented with analysis of residues, the Student t test; to determine and evaluate multiple risks, we used a logistic regression analysis using the variables that in the bivariate analysis showed a significant association. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Complications were presented in the postoperative period by 62 patients (21%), corresponding to 29 hypoparathyroidisms (2 permanent), 26 RLN injury (1 permanent), 4 lesions of the superior laryngeal nerve, 3 cervical hematomas, and 1 cervicotomy infection. There was no mortality in the perioperative period. The mean postoperative stay was 2.9 ± 1.2 days.1–15

After the bivariate analysis the risk factors for the development of complications were presence of symptoms (P = 0.0131), hyperthyroidism (P = 0.0033), presence of compressive symptoms (P = 0.0455), intrathoracic goiter (P = 0.0336), cervical goiter grade (P = 0.0195), and weight of excised thyroid specimen (P = 0.0302) (Table 1). After the multivariate analysis, hyperthyroidism (OR = 2.5; CI = 4.05 to 1.56) and intrathoracic component (OR = 1.6; CI = 2.06 to 1.17) persisted as independent risk factors (Table 2).

TABLE 1. Variables Associated With Postoperative Complications; Bivariate Analysis

TABLE 2. Variables Associated With Postoperative Complications; Multivariate Analysis

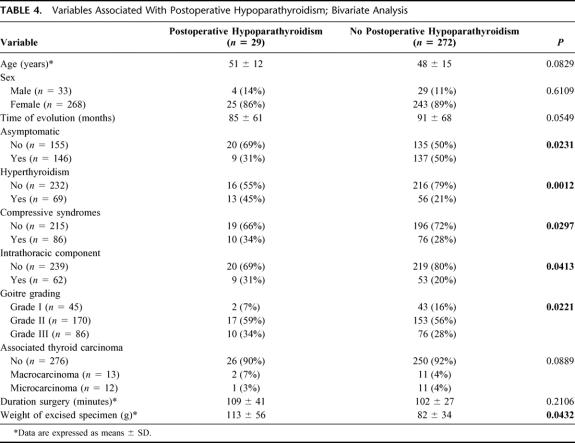

None of the patients had symptoms with calcemia above 7.5 mg/dl. Twenty-nine cases (9.6%) presented with calcemia below 7.5 mg/dl (7.3 ± 0.1 mg/dl), 4 of whom had symptoms (calcemia 7.1 ± 0.2 mg/dl). None of the 3 patients receiving a parathyroid autotransplant presented with hypoparathyroidism, with 24-hour calcemia figures of 7.9 mg/dl, 8 mg/dl, and 8.4 mg/dl, respectively, figures that returned to normal in subsequent controls. Most of the hypoparathyroidisms returned to normal blood calcium readings when the calcium and vitamin D treatment was discontinued in the third month. The 5 patients who at 3 months had not shown a return to normal calcemia without treatment underwent monthly determinations of intact parathyroid hormone (PTHi). It can be seen that the 3 cases in which calcemia recovered without treatment had PTHi readings at 1 year of 57 to 62 pg/ml (Nr = 10 to 65 pg/ml), whereas those with definitive hypoparathyroidism remained below 10 pg/ml (Table 3). As risk factors for the development of postoperative hypoparathyroidism, we noted presence of symptoms (P = 0.0231), hyperthyroidism (P = 0.0012), compressive symptoms (P = 0.0297), intrathoracic goiter (P = 0.0413), goiter grade on physical exploration (P = 0.0221), and weight of excised thyroid specimen (P = 0.0432) (Table 4), with hyperthyroidism (OR = 1.9; CI = 3.01 to 1.27), clinical goiter grade (OR = 1.3 [CI = 7.17 to 0.24]; OR = 3.2 [CI = 7.39 to 1.39]), and weight of excised thyroid specimen persisting as independent factors (Table 5).

TABLE 3. Evolution of PTHi Figures in Patients With Hypoparathyroidism 3 Months After Surgery

TABLE 4. Variables Associated With Postoperative Hypoparathyroidism; Bivariate Analysis

TABLE 5. Variables Associated With Postoperative Hypoparathyroidism; Multivariate Analysis

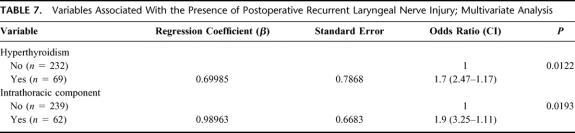

There were 26 RLN injuries (8.6%), 16 patients (62%) affected on the right side and the rest on the left; there was no bilateral recurrent paralysis. In the 5 previous dysphonias, laryngoscopy confirmed that they were related to the paralysis diagnosed preoperatively, which is why they were not considered a complication. Most of the dysphonias abated in the first 2 months (2.7 ± 2.9 months), and the control laryngoscopy at 6 months showed a return to normality of the mobility of all the vocal chords except two, the paralysis that turned out to be definitive, and a transitory paralysis that disappeared at 8 months. The factors that favored the appearance of this recurrent lesions were the presence of symptoms (P = 0.0113), hyperthyroidism (P = 0.0211), compressive symptoms (P = 0.0327), intrathoracic goiter (P = 0.0341), clinical goiter grade (P = 0.0222), and weight of excised thyroid specimen (P = 0.0432) (Table 6), with hyperthyroidism (OR = 1.7; CI = 2.47 to 1.17) and goiter with intrathoracic component (OR = 1.9; CI = 3.25 to 1.11) persisting as independent risk factors for RLN injury (Table 7). Of the 5 patients presenting with preoperative dysphonia, 4 recovered their vocal chord mobility, with laryngoscopic confirmation, 1 year after surgery.

TABLE 6. Variables Associated With the Presence of Postoperative Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve Injury; Bivariate Analysis

TABLE 7. Variables Associated With the Presence of Postoperative Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve Injury; Multivariate Analysis

Definitive complications occurred in 3 patients (1%), corresponding to 2 hypoparathyroidisms (0.7%) and 1 RLN injury (0.3%). Due to the small number of patients, it was not possible to perform bivariate or multivariate statistical analyses to detect the risk factors. Table 8 summarizes the main characteristics of these 3 cases, particularly the fact that they were toxic and/or intrathoracic goiters.

TABLE 8. Definitive Postoperative Complications

DISCUSSION

Surgery for MG currently lies between ST, which has a high percentage of recurrences, and TT, which has a high percentage of postsurgical complications. The defenders of ST claim that with a small thyroid remnant the rates of clinical recurrence requiring surgery do not exceed 4%.17–20 To reduce these recurrences, there are authors who consider the procedure of choice to be the Dunhill technique,21–22 although its use is not so widespread because it presents a higher rate of postoperative complications and hypothyroidisms.

TT, with an appropriate period of learning, can be performed with minimum definitive complications (1%), as seen in the present study. The few existing prospective studies3–4 that analyze the results of TT in MG performed by surgeons with experience in endocrine surgery, after excluding the period of learning, coincide with our results. Delbridge et al3 in a series of 3089 thyroidectomies (1838 STs and 1251 TTs) report 0.5% permanent RLN injury and 0.4% hypoparathyroidism, in other words 0.9% definitive complications. Furthermore, 205 STs (11%) required reoperation due to recurrence. Our rate of definitive complications lies within this range, with 0.7% definitive hypoparathyroidisms and 0.3% definitive dysphonias, in other words 1%. We therefore agree with Delbridge et al,3 who consider TT to be the choice for MG, because the only real argument against it, ie, the greater risk of complications, does not now occur in centers with experience. TT thus represents the definitive treatment of goiters, prevents recurrences, and, in the event of malignancy, may be a correct treatment with a low rate of associated morbidity.1,3,10–13,23–25

The overall complication rate in surgery for MG is approximately 21% in our department. This rate is in the higher range of the bibliography, and this is partly because the concept of transitory hypoparathyroidism that we use is not as restrictive as in other series, we include wound complications in the overall rate, we have a high percentage of intrathoracic and toxic goiters, and the surgical technique is TT, in which transitory complications are the most frequent.26

Our percentage of hypoparathyroidism was 9.6%, with 0.7% turning out to be definitive. We regarded as such when calcemia was less than 7.5 mg/dl, since below this figure the risk of developing hypocalcemia-related clinical symptoms is high. Transitory hypocalcemia may be more frequent in toxic MGs and is related to the severity of the thyrotoxicosis.27 The rate of postoperative RLN injury was 8.6%, and 0.3% turned out to be permanent (n = 1). If we want to accurately identify the number of recurrent lesions, both transitory and definitive, we must perform routine laryngoscopy after surgery, as there may be compensated recurrent lesions and therefore no alteration in the voice. All the cases in our series had alteration in the tone, timbre, or intensity of their voice before laryngoscopic confirmation. However, Steurer et al28 show that 11 patients from 608 undergoing surgery (1.8%) presented with vocal chord alteration with a normal voice.

Hyperthyroidism is the main independent risk factor in our study for the development of complications, both transitory and definitive. Like us, Thomusch et al9 show in a multivariate study in Germany that hyperthyroidism is a risk factor for the development of surgical complications and hypoparathyroidism (relative risk, 2.8) but not RLN injury. Although there are authors30 who do not find that toxic MGs have a greater risk for RLN injury, most studies show a higher rate of these lesions (4 to 13%).7,10,29 Our series also shows that the highest rate of cervical bleeding occurs in hyperthyroidism, with 2 of the 3 cases. This has also been described in the bibliography and is attributed to the greater thyroid vascularization of these goiters.9

Goiter size is another risk factor; in our study, it is assessed as intrathoracic component, goiter grade, or weight of the excised thyroid. These 3 aspects are risk factors in the bivariate analyses of the complications, both in the overall study and in hypoparathyroidism and dysphonia, with one of them always persisting as an independent risk factor, especially the intrathoracic component (Tables 1–8). McHenry et al31 showed an increase in postoperative hypoparathyroidism in large (>100 g) and intrathoracic goiters.

If we analyze the various known potential risk factors, we see that neither sex nor age act as such in our series. We do not confirm the results of Thomusch et al9 or Hermann et al,32 who observe that female sex is an additional risk factor for the development of complications, multiplying the risk of transitory RLN injury by 1.4 and hypoparathyroidism by 2–2.3.

Simple goiters are reported to have significantly fewer complications than toxic goiters and thyroid carcinomas.7,10,32 Our observations were that patients with a simple goiter—not toxic or intrathoracic—had a zero rate of definitive complications.

Other risk factors reported include the hospital's volume of operations and the surgeon's experience. However, these are not factors that can be assessed in our series, as all the patients were operated on in the same center (a hospital with a high rate of endocrine surgery) and by the same professionals.9,12,33

It is a fundamental principle of surgery that a structure must be identified clearly in order not to damage it. However, routine identification of the parathyroid glands and recurrent nerves has not always been accepted. Various authors fail to observe9 that the intraoperative identification of parathyroid glands affects the rate of hypoparathyroidism. To reduce this incidence of hypoparathyroidism, it has been suggested performing parathyroid autotransplantation at the sternocleidomastoid muscle of any parathyroid excised or without viable vascularization.2,34,35 In this series of MGs, it was done in 3 patients. There is also no consensus on the utility of routine identification of the recurrent nerve. Although identification has been associated with a lower rate of complications9,28,36 and is crucial during extracapsular resection or resection of the posterior nodules,9,32,29,37 there are authors such as Torre et al37 who do not consider it necessary, since manipulation can lesion them. Megherbi et al38 and Kasemsuwan et al39 did not find a higher or lower rate of recurrent paralysis if identified systematically. Both recurrent nerves were routinely identified in our series. Performing capsular dissection of the thyroid is currently recommended, because the recurrent nerve is always extracapsular, the same as vascularization of the parathyroids, bearing in mind that the nerve passes behind Zuckerlandl's tuberculum lateral to Berry's ligament.40

In conclusion, we can say that TT for MG can be performed in endocrine surgery units with a definitive complication rate of 1%. Hyperthyroidism and goiter size are the 2 independent risk factors for the development of complications. TT can be performed by surgeons with experience in endocrine surgery in non-intrathoracic euthyroid MG with a definitive complication rate close to 0%.

Footnotes

Reprints: Dr. Antonio Ríos Zambudio Avenida de la Libertad n° 208, Casillas, 30007, Murcia. E-mail: arzrios@teleline.es.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gardiner KR, Russell CF. Thyroidectomy for large multinodular colloid goitre. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1995;40:367–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Q, Djuricin G, Prinz R. Total thyroidectomy for benign thyroid disease. Surgery. 1998;123:2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delbridge L, Guinea AI, Reeve TS. Total thyroidectomy for bilateral benign multinodular goiter. Arch Surg. 1999;134:1389–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reeve TS, Delbridge L, Cohen A, Crummer P. Total thyroidectomy: the preferred option for multinodular goiter. Ann Surg. 1987;206:782–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson SB, Staren ED, Prinz RA. Thyroid reoperations: indications and risks. Am Surg. 1998;64:674–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harness JK, Fung L, Thompson NW, et al. Total thyroidectomy: complications and technique. World J Surg. 1986;10:781–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagner HE, Seiler CA. Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy after thyroid gland surgery. Br J Surg. 1994;81:226–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seiler CA, Glaser C, Wagner HE. Thyroid gland surgery in an endemic region. World J Surg. 1996;20:593–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomusch O, Machens A, Sekulla C, et al. Multivariate analysis of risk factors for postoperative complications in benign goiter surgery: prospective multicenter study in Germany. World J Surg. 2000;24:1335–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mishra A, Agarwal A, Agarwal G, Mishra SK. Total thyroidecotmy for benign thyroid disorders in an endemic region. World J Surg. 2001;25:307–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menegaux F, Turpin G, Dahman M, et al. Secondary thyroidectomy in patients with prior thyroid surgery for benign disease: a study of 203 cases. Surgery. 1999;125:479–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sosa JA, Bowman HM, Tielsch JM, et al. The importance of surgeon experience for clinical and economic outcomes from thyroidectomy. Ann Surg. 1998;228:320–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergamaschi R, Becouarn G, Ronceray J, Arnaud JP. Morbidity of thyroid surgery. Am J Surg. 1998;176:71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reeve T, Thompson NW. Complications of thyroid surgery: how to avoid them, how to manage them, and observations on their possible effect on the whole patient. World J Surg. 2000;24:971–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin L, Delbridge L, Martin J, et al. Trainee surgery: is there a cost? Aust N Z J Surg. 1989;59:257–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahan M, Gaillard J, Eschapase H. Surgical treatment of goiters with intrathoracic development. In: Delarue NC, Eschapase H, eds. Thoracic Surgery: Frontiers and Uncommon Neoplasms. International Trends in General Thoracic Surgery. St Louis: Mosby; 1989:5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen R, Schachter P, Sheinfeld M, et al. Multinodular goiter: the surgical procedure of choice. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:848–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kraimps JL, Marechaud R, Gineste D, et al. Analysis and prevention of recurrent goiter. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1993;176:319–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piraneo S, Vitri P, Galimberti A, et al. Recurrence of goitre after operation in euthyroid patients. Eur J Surg. 1994;160:351–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lasagna B. Subtotal thyroidectomy, the preferred option for eu- and hyperthyroid goitre. Panminerva Med. 1994;36:22–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banerjee A, Cooper J. Nonsurgical treatment of multinodular nontoxic goitre. Postgrad Med J. 1995;71:643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prades JM, Dumollard JM, Timoshenko A, et al. Multinodular goiter: surgical management and histopathological findings. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;259:217–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hisham AN, Azlina AF, Aina EN, et al. Total thyroidectomy: the procedure of choice for multinodular goitre. Eur J Surg. 2001;167:403–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wheeler MH. Total thyroidectomy for benign thyroid disease. Lancet. 1998;351:1526–1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bononi M, de Cesare A, Atella F, et al. Surgical treatment of multinodular goiter: incidence of lesions of the recurrent nerves after total thyroidectomy. Int Surg. 2000;85:190–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhattacharyya N, Fried MP. Assessment of the morbidity and complications of total thyroidectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:389–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mittendorf EA, McHenry CR. Thyroidectomy for selected patients with thyrotoxicosis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:61–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steurer M, Passler C, Denk DM, et al. Advantages of recurrent laryngeal nerve identification in thyroidectomy and parathyroidectomy and the importance of preoperative and postoperative laryngoscopic examination in more than 1000 nerves at risk. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:124–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sturniolo GS, D′Avila C, Tonante A, et al. The recurrent laryngeal nerve related to thyroid surgery. Am J Surg. 1999;177:485–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deus Fombellida J, Gil Romea I, García Algara C, et al. Aspectos quirúrgicos de los bocios multinodulares. A propósito de una serie de 680 casos. Cir Esp. 2001;69:25–29. [Google Scholar]

- 31.McHenry CR, Piotrowski JJ. Thyroidectomy in patients with marked thyroid enlargament: airway management, morbidity, and outcome. Am Surg. 1994;60:586–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hermann M, Keminger K, Kober F, et al. Risikofaktoren der Rekurrensparese. Eine statistische analyse an 7566 struma operationen. Chirurg. 1991;62:182–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McHenry CR. Patient volumes and complications in thyroid surgery. Br J Surg. 2002;89:821–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh B, Lucente FE, Shaha AR. Substernal goiter: a clinical review. Am J Otolaryngol. 1994;15:409–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torre G, Borgonovo G, Amato A, et al. Surgical management of substernal goiter: analysis of 237 patients. Am Surg. 1995;61:826–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hermann M, Alk G, Roka R, et al. Laryngeal recurrent nerve injury in surgery for benign thyroid diseases: effect of nerve dissection and impact of individual surgeon in more than 27,000 nerves at risk. Ann Surg. 2002;235:261–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wheeler MH. Thyroid surgery and the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Br J Surg. 1999;86:291–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Megherbi MT, Graba A, Abid L, et al. Complications et sequelles de la chirurgie thyroidienne benigne. J Chir Paris. 1992;129:41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kasemsuwan L, Nubthuenetr S. Recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis: a complication of thyroidectomy. J Otolaryngol. 1997;26:365–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pelizzo MR, Toniato A, Gemo G. Zuckerkandl′s tuberculum: an arrow pointing to the recurrent laryngeal nerve. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:333–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]