Abstract

Objective:

We began a controlled clinical trial to assess efficacy and toxicity of surgery (S), surgery + radiotherapy (SRT), surgery + chemotherapy (SCT), and chemotherapy (CT) in the treatment of primary gastric diffuse large cell lymphoma in early stages: IE and II1.

Summary Background Data:

Management of primary gastric lymphoma remains controversial. No controlled clinical trials have evaluated the different therapeutic schedules, and prognostic factors have not been identified in a uniform population.

Patients and Methods:

Five hundred eighty-nine patients were randomized to be treated with S (148 patients), SR (138 patients), SCT (153 patients), and CT (150 patients). Radiotherapy was delivered at doses of 40 Gy; chemotherapy was CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) at standard doses. International Prognostic Index (IPI) and modified IPI (MIPI) were assessed to determine outcome.

Results:

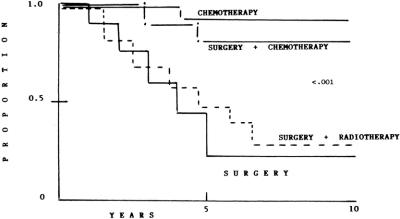

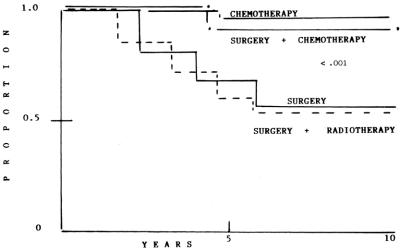

Complete response rates were similar in the 4 arms. Actuarial curves at 10 years of event-free survival (EFS) were as follows: S: 28% (95% confidence interval [CI], 22% to 41%); SRT: 23% (95% CI, 16% to 29%); that were statistically significant when compared with SCT: 82% (95% CI, 73% to 89%); and CT: 92% (95% CI, 84% to 99%) (P < 0.001). Actuarial curves at 10 years showed that overall survivals (OS) were as follows: S: 54% (95% CI, 46% to 64%); SRT: 53% (95% CI, 45% to 68%); that were statistically significant to SCT: 91% (95% CI, 85% to 99%); CT: 96% (95% CI, 90% to 103%)(P < 0.001). Late toxicity was more frequent and severe in patients who undergoing surgery. IPI and MIPI were not useful in determining outcome and multivariate analysis failed to identify other prognostic factors.

Conclusion:

In patients with primary gastric diffuse large cell lymphoma and aggressive histology, diffuse large cell lymphoma in early stage SCT achieved good results, but surgery was associated with some cases of lethal complications. Thus it appears that CT should be considered the treatment of choice in this patient setting. Current clinical classifications of risk are not useful in defining treatment.

We evaluate in a large controlled clinical trial the most common therapeutic schedules in primary gastric lymphoma: surgery, surgery and radiotherapy, surgery and chemotherapy, and chemotherapy. Long-term follow-up showed that surgery and surgery plus radiotherapy had the worse outcome; although surgery and chemotherapy showed similar results to chemotherapy, presence of late lethal events associated with surgery suggested that chemotherapy appears to be the best treatment in primary gastric lymphoma.

The gastrointestinal tract is the most common extranodal presentation of malignant lymphoma and accounts for 7 to 20% of all malignant lymphomas. Primary gastric lymphoma (PGL) is the most frequent presentation in gastrointestinal tract. For many years, PGL was classified according to the criteria of the Working Formulation as intermediate-grade (diffuse large cell) and high-grade (inmunoblastic); Isaacson and Wright introduced the concept of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT tumor) with a different clinical and biologic course.1 Moreover, transformation to high-grade MALT lymphoma is frequent, and this histologic type has been confused with diffuse large cell lymphoma. Low-grade MALT gastric lymphoma and high-grade transformed MALToma lymphoma have a different clinical course to patients with diffuse large cell lymphoma, thus management will be considered to be different.2 The best management of PGL has yet not been established. Most reports of PGL involve retrospective analysis of a limited number of patients treated by different methods, including different histology, stages, and treatment.3–18 The International Prognostic Index (IPI) was developed to assess clinical risk in patients with diffuse large cell lymphoma (DLCL); however, PGL results have been considered confusing. Miller et al modified the IPI to identify prognostic factors in patients with DLCL at early stages (I and II) with extranodal presentation.19 Factors evaluated were age > 60 year, stage II, increased serum lactate dehydrogenase level (LDH), and decreased performance status. Patients with more than 1 point had high risk, and patients with 0 or 1 point were considered as low-risk. Cortelazzo et al applied this modified IPI (MIPI) to patients with gastric and intestinal lymphoma20,21 and confirmed that MIPI can be useful to determine outcome. However, Castrillo et al did not confirm these findings.22 In our experience with gastric,23 intestinal,24 and large bowel lymphoma,25 we cannot identify any prognostic factor, including IPI that can define treatment (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1. Kaplan-Meier actuarial curves of event-free survival, according to treatment.

Thus we start a controlled clinical trial to assess efficacy and toxicity of the most frequent therapeutic approaches in PGL: surgery (S), surgery and radiotherapy (SRT), surgery and chemotherapy (SCT), and chemotherapy (CT) in patients with DLCL. Analysis of IPI and MIPI were performed to evaluate the usefulness in this setting of patients. Results with a long follow-up are presented here.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

From June 1985 to December 1996, patients with a diagnosis of PGL were considered for the study if they fulfilled the following criteria: diagnosis of diffuse large cell lymphoma (see below); age > 18 to 70 years; no gender difference; previously untreated; stage IE and II1 (see below); performance status < 2 from 1988 inmunodeficiency virus test was mandatory; normal hepatic, renal, pulmonary, and cardiac functions.

Pathology

Patients were initially classified according to the Working Formulation as intermediate-grade (diffuse large cell lymphoma) and high-grade (inmunoblastic) lymphoma. In 1999, all pathologic materials were reviewed (IC and IA), and patients with MALT-type gastric lymphoma and patients with large cells but with foci of follicular cells were considered a high-grade MALT type and were excluded. Thus only patients who were CD10 + (“pure” diffuse large cell lymphoma) were included to the present study.14

Stage

Patients were classified initially according to the Musshoff's criteria. In 1995, patients were classified according to the Lugano Conference Workshop.26 Stage IE included patients with lymphoma confined to a single organ of the gastrointestinal tract (stomach). In stage II, lymphoma was extended into the abdomen involving local (perigastric) II1 or distant II2 (mesenteric, paraortic) nodal sites. In the present study, we included only patients with stage IE and II1 because we felt that II2 and IIE will be considered as disseminated disease (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2. Overall survival.

Staging

Routine staging procedures included: physical examination; complete blood count; liver and renal profile; serum determination of LDH and Azā2-microglobulin (normal values < 3.5 μg/mL; computed tomography of thorax, abdomen, and pelvis; aspirate and bone marrow biopsy. Determination of HIV test was mandatory from 1988. In all patients before surgery, diagnosis of PGL was performed on the basis of endoscopic biopsies. Multiple biopsies (at least 12) were taken for evident lesion, and 12 more were obtained from local distant sites of stomach from apparent noninfiltrate tissue. In all cases, the diagnosis was based on morphologic and immunophenotypic analysis of paraffin-embedded sections.

Gastric lymphoma were classified as one of the following subtypes: a, low grade MALT lymphoma with or without small focci of large cell; b, high-grade MALT lymphoma formed by more than 25% of large cells but with foci of low-grade type MALToma; or c, diffuse large cell lymphoma, only large cells observed, without foci of low-grade MALToma.27 Immunostaging was performed with a battery of monoclonal and policlonal antibodies: CD3, CD5, CD10, CD26, CD23, L26 (specificity CD20), and cytokeratin.

Prognostic Factors

When the study was started, defined criteria for prognostic factors were not identified. Our patients were retrospectively analyzed according to the IPI and MIPI, but the treatment was defined according to stage.

Helicobacter pylori was not considered initially, and only a few patients were studied. The end points of the present study were complete response rate, event-free survival, OS, and late toxicity associated to treatment. Criteria for entry to the protocol and exclusion criteria were defined as mentioned.

Treatment

In all cases, diagnosis of malignant lymphoma was performed after staging based in endoscopic biopsy. Patients were then randomized to receive any of the following therapeutic approaches.

Surgery

Surgery intended to achieve a complete resection of gastric tumor was performed. The location and the extent of the gastric tumor as well the normal safety margins determined the extent of the resection: total versus partial gastrectomy. An intraoperative rapid section examination of the resection margins and lymph node resection in compartment I and II were mandatory. Biopsies of omentum for any suspicious lesion and liver biopsy were obligatory. Splenectomy was performed in some cases. Complete resection was achieved, and the surgeon felt that no residual tumor was evident. No further treatment was considered.

Surgery and Radiotherapy

The patient was received the same surgery as described above. One month later, radiotherapy was administered: 20 Gy to abdomen following by a boost of 20 Gy to the gastric bed; radiation therapy was administered with a 6 MeV or 8 MeV.

Surgery and Chemotherapy

After the same surgery, they received adjuvant chemotherapy: CHOP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and prednisone) at standard doses every 21 days for 6 cycles.

Chemotherapy

Diagnosis and staging were performed as described; if the patient fulfilled the entry criteria, they received the same chemotherapy as described above.

The response to treatment was assessed postoperatively or 1 month after radiation therapy or chemotherapy were administered. Complete response (CR) was defined as the total disappearance of all sites initially positive with normalization of any laboratory or radiologic findings that were initially abnormal. Failure was defined as the appearance of new signs of lymphoma in any sites (local, intraabdominal, disseminated) during treatment or the persistence of >25% of initial tumor.

Statistical Analysis

Event-free survival was considered when the patient achieved CR until the date of relapse, failure, death from any cause, or last follow-up (August 2002). OS was considered from the date of diagnosis to the date of death from any cause. Statistical comparison of nominal data between subgroups was performed using the ÷2 test. To estimate the effects of treatment, intention to treat analysis was applied in all patients. In this analysis, life-table survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and differences between survival curves with regard to the effects of treatment was established at P < 0.05. The statistical package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Inc, Cary NC) software program was used for analysis.

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of our Institution, and all patients signed informed consent to participate in the study.

RESULTS

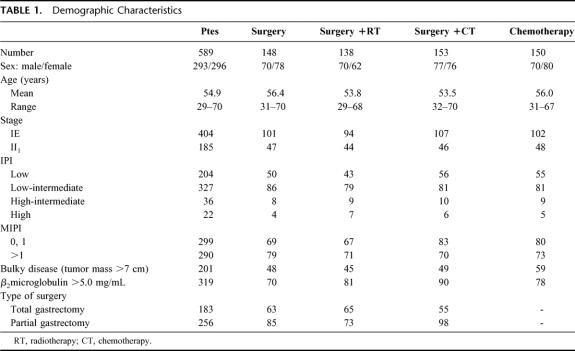

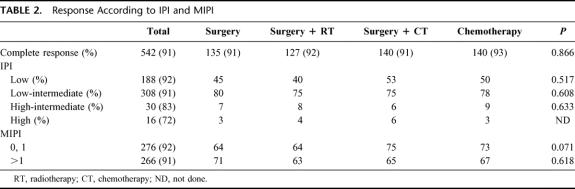

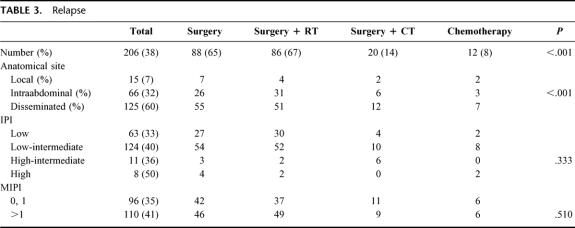

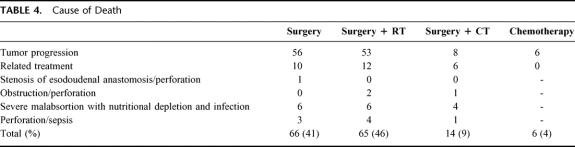

Between June 1985 and December 1996, 1160 cases of PGL were diagnosed in the Oncology Hospital, National Medical Center. Two hundred eleven were classified as MALToma gastric lymphoma; 186 were classified as high-grade with MALToma component; 174 were considered advances stages (III and IV) and were not considered candidates for this study. Thus 589 patients were considered candidates; in an intent to treat analysis, all patients were considered evaluable. The most important clinical characteristics can be seen in Table 1. No statistical differences were observed between the different arms. As expected, low and low-intermediate clinical risk according to the IPI were more frequent. No differences were observed between low-risk and high-risk according to the MIPI. Moreover, 34% of patients had bulky disease, and 54% high levels of Azā2-microglobulin. Table 2 shows the CR rate according to treatment schedule and prognostic models. No statistical differences were observed in the 4 arms of the study and again when they were analyzed according to IPI and MIPI. Two hundred six patients (38%) have relapsed (Table 3). The most frequent site of relapse was as disseminated disease: 125 cases (60%). Statistical differences were observed when comparing S and SRT versus SCT and CT (P < 0.001); however, no statistical differences were observed in the relapse type according to IPI and MIPI (Table 3). Salvage treatment consisted generally of conventional chemotherapy: CHOP in patients who did not receive previous chemotherapy. Intensive, nonmyeloablative regimens were employed in patients that received previously chemotherapy. Eighty-five patients achieve a second CR (38%), second response was no different in relationship to IPI or MIPI (data not shown). Acute toxicity was common to therapeutic approaches and can be considered moderate. Recovery was observed in all cases, and no death-related treatments were observed, including surgical procedures. Nevertheless, late toxicity was seen in patients undergoing surgery. The most common were malabsorption syndrome (24 cases) and “dumping syndrome” (28 cases). Twenty-eight patients died secondary to surgical procedures. Table 4 shows the cause of death; we named “related treatment” because no evidence of another disease was observed at surgery (when indicated) or autopsy; also, no evidence of lymphoma relapse was documented. The frequency of this type of complication after gastric surgery could be considered higher, but it did not have another explanation. On the other hand, long-term follow-up is not available in most studies of PGL, and we cannot determine if in these studies late complications were or were not observed or simply not reported. Total or partial gastrectomy did not influence the presence of severe and late complications; in patients with total gastrectomy, we observed 10 deaths (5.9%), not different than 6.9% of patients with partial gastrectomy (18 deaths) (P = 0.088). Actuarial curves at 10 years showed that EFS was as follows: S: 28% (95% confidence interval [CI], 22 to 41%); SRT: 23% (95% CI, 16 to 29%) were statistically significant to the observed in SCT (82% [95% CI, 73 to 89%]); and CT (92% [95% CI, 84 to 99%]) (P < 0.001). No statistically significant differences were observed between SCT and CT.

TABLE 1. Demographic Characteristics

TABLE 2. Response According to IPI and MIPI

TABLE 3. Relapse

TABLE 4. Cause of Death

One hundred fifty-four patients died, 126 secondary to tumor progression, and 28 related to treatment (Table 4). Actuarial curves at 10 years show that OS was as follows: S: 54% (95% CI, 46 to 64%,); SRT: 53% (95% CI, 45 to 65%) were statistically significant when compared with SCT (91% [95% CI, 85 to 99%]) and CT (96% [95% CI, 90 to 102%]) (P < 0.001); again, no differences were observed between SCT and CT.

Multivariate analysis was performed to define presence of adverse prognostic factors: age, sex, stage, IPI, MIPI, bulky disease, B symptoms, levels of LDH and Azā2-microglobulin and therapy, and only therapy was significant.

DISCUSSION

Treatment of PGL remains controversial. For several years, surgery played a central role in diagnosis, staging, and treatment of PGL. Its goal in these tumors has gradually changed from curative to staging and palliation, with less concern for radicality.5,7–9,11,13,15,17,18 However, in patients with gastric MALToma, the role of surgery remains central, because EFS and OS have been reported to be excellent.3,10,12 Surgery has been indicated for 3 different situations in PGL; a primary radical treatment; as urgent treatment of patients presenting severe bleeding or perforation; and as palliative treatment.8,10 Nevertheless, with the supportive care available today, these complications could be considered to be a low number. In our patients, no surgery was performed for bleeding or perforation, and the complications observed are common in this type of surgery.

Surgery was considered necessary to diagnosis and staging; in the first case, modern endoscopy procedures permitting histology diagnosis. In the present study, all cases can be diagnosed without surgery; probably because in our population multiple biopsies were performed, including sites apparently noninvolved. Thus surgery for diagnosis appears to be not necessary.

The main advantage claimed for surgery is to discriminate accurately among stages I, II1, and II2, because lymph nodes adjacent to the stomach cannot be visualized by noninvasive methods. However, with computed tomography and the introduction of endoscopic ultrasound, the sensitivity could be > 95%. On the other hand, no differences in EFS and OS were observed between stages I and II1, and stage II2 has been considered to be advanced.10,15,16,26 Thus surgery it is not necessary to define I or II1 because patients could receive chemotherapy that eliminate these as prognostic factor. Multiple studies have been reported about treatment of PGL; however, most studies including patients with gastric, intestinal and large bowel lymphoma, mixed histology (MALT, high-grade MALT, and diffuse large cell lymphoma) stages (I, II1, and II2), surgical techniques: gastrectomy total or subtotal; thus, it is very difficult to draw definitive conclusions. Recently, Fischbach defined treatment after surgery, and management of the tumor was determined according to stage, histology, or presence of residual tumor. These results were better because patients with aggressive histology, advanced stage, or residual tumor received adjuvant radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy; patients without residual tumor, low-grade histology, and early stage received only surgery.16

Nevertheless, a considerable percentage of patients have localized advanced high-grade lymphoma in which curative surgery is not possible, probably because of these lymphomas’ different growth dynamic. On the other hand, the presence of disseminated disease at relapse suggests that, although PGL could be considered in early stages, some patients can have foci of tumor cells in another anatomic site. Our results show that S and SRT appear to be inadequate for patients with PGL, even in early stage, because the EFS and OS were worse when compared with SCT and CT. Intraabdominal and disseminated relapse were frequent; even the surgeon felt that no residual tumor was evident and the restaging studies were negative, thus it is probable that microscopic disease remains and that the use of regional treatment was insufficient. The use of SCT and CT showed the same EFS and OS; however, the presence of late toxicity associated with surgery will be considered as a risk. As mentioned, some of these late complications could not be considered in previous reports; for example, presence of severe malabsorption syndrome causing nutritional depletion and secondary infection can be delegated to an internal medicine service for treatment. Thus, if the patient died while under the care of another service or had late surgical complications (5 years), such as obstruction and/or perforation are omitted as complication to initial surgery, it was not included in these reports.

On the other hand, the use of CT alone allows retention of the stomach with an excellent EFS and OS. Considering that no relapse has been observed after 3 years, more that 90% of these patients can be considered cured. Ferreri et al10 and Raderer et al13 have reported the same results with chemotherapy as primary treatment in PGL. Moreover, our study is the first to include a uniform population of patients: only DLCL, early stage, uniform treatment, and large follow-up.

The IPI was developed to assess clinical risk and define treatment in patients with nodal diffuse large cell lymphoma. Patients with low and low-intermediate clinical risk can be treated with conventional therapy; patients at high-intermediate and high clinical risk will be considered for more aggressive or experimental therapy. Miller et al19 introduced a modified IPI, the so-called MIPI, that was employed in patients with nodal and extranodal lymphoma. Cortelazzo et al confirmed the usefulness of MIPI in gastric20 and intestinal lymphoma,21 but in these studies patients with different histology, stage and treatment were analyzed. In our study, we could not demonstrate that IPI or MIPI defines treatment, possibility of CR rate, relapse, response to second line of treatment, and more important EFS and OS in patients with PGL.

Finally, our long-term follow-up showed that the probability of relapse in these patients is low and most of these patients could be considered cured. In light of these results, we considered that the treatment of choice in patients with early stage PGL and diffuse large cell lymphoma is chemotherapy, which prolongs EFS and OS without excessive acute and late toxicity and conserves stomach. Surgery should be considered in the staging and treatment of selected cases.

Footnotes

Reprints: Agustin Avilés, MD, Plaza Luis Cabrera 5-502, Colonia Roma, 06700, México, D.F.Mexico; E-mail: agaviles@avantel.net.

REFERENCES

- 1.Isaacson PG, Wright DH. Extranodal malignant lymphoma arising from mucossa-associated lymphoid tissue. Cancer. 1984;53:2515–2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Isaacson PG. Recent development in our understanding of gastric lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;20:S1–S7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheperd FA, Evans WK, Kutas G, et al. Chemotherapy following surgery for stages IE and IIE non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract. J Clin Oncol. 1988;6:253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amer MG, El-Akkar S. Gastrointestinal lymphoma in adults. Clinical features and management in 300 cases. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:846–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rigacci L, Bellesi G, Alterini R, et al. Combined surgery and chemotherapy in primary gastric non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: A retrospective study in sixty-six patients. Leuk Lymph. 1994;14:483–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosen CB, Heerden JA, Martin JK, et al. Is an aggressive surgical approach to the patients with gastric lymphoma warranted? Ann Surg. 1987;208:634–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasini F, Ambrosetti A, Sabbioni R, et al. Postoperative chemotherapy increase the disease-free survival rate in primary gastric lymphoma stage IE and IIE. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A:33–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gobi PG, Dionigi P, Barbieri F, et al. The role of surgery in the multimodal treatment of primary gastric non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cancer. 1990;65:2528–2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maor ME, Velasquez WS, Fuller LM, et al. Stomach conservation in stages IE and II2 gastric non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:266–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferreri AJM, Cordio S, Paro S, et al. Therapeutic management of stage I-II high grade primary gastric lymphoma. Oncology. 1999;56:274–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Popesco RA, Wotherspon AC, Cunningham D, et al. Surgery plus chemotherapy or chemotherapy alone for primary intermediate- and high-grade gastric non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. The Royal Marsden experience. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:928–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ranaldi R, Guteri G, Baccarini MG, et al. A clinicopathological study of surgically treated primary gastric lymphoma with survival analysis of 109 high-grade tumors. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:346–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raderer M, Valencak J, Österreucher C, et al. Chemotherapy for the treatment of patients with primary high-grade gastric B cell lymphoma of modified Ann Arbor stages IE and IIE. Cancer. 2000;88:1979–1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takeshita M, Iwashita A, Kurihara K, et al. Histologic and immunohistologic findings and prognosis of 40 cases of gastric large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1641–1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaillart JC, Ruskoné-Fourmetraux A, Aegerter P, et al. Management and long term results of surgery for localized gastric lymphoma. Am J Surg. 2000;179:216–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischbach W, Dragosics B, Kolve-Goedeler ME, et al. Primary gastric B-cell lymphoma. Results of a prospective multicenter study. Gastroenterology. 2001;119:1191–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lyberg MLM, DeNeve W, Vrints LW, et al. Primary gastric non-Hodgkin's lymphoma stages IE and IIE. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:2306–2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koch P, del Valle F, Bersel WE, et al. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. II: Combined surgical and conservative management only in localized gastric lymphoma. Results of the prospective German Multicentre Study GIT NHL 01/92. J Clin Oncol. 2001;18:3874–3887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller TP, Dalhberg S, Cassady JR, et al. Chemotherapy alone compared with chemotherapy plus radiotherapy for localized intermediate- and high-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cortelazzo S, Rossi A, Roggero R, et al. Stage-modified International Prognostic Index effectively predicts outcome of localized primary gastric diffuse large cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:1433–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cortelazzo S, Rossi A, Oldani E, et al. The Modified International Prognostic Index can predict the outcome of localized intestinal lymphoma of both extranodal marginal B-cell and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2002;118:218–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castrillo JM, Montalban C, Abraira V, et al. Evaluation of the International Index in the prognosis of high-grade gastric MALT lymphoma. Leuk Lymph. 1996;24:159–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Avilés A, Narvaéz B. Beta 2 microglobulin and lactate dehydrogenase levels are useful prognostic markers in early stage primary gastric lymphoma. Clin Lab Haematol. 1998;20:297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Avilés A, Nambo MJ, Rosas A, et al. Combined surgery and chemotherapy in the treatment of primary intestinal malignant lymphoma. GI Cancer. 1995;1:45–48. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Avilés A, Neri N, Huerta-Guzmán J. Large bowel lymphoma. An análisis of prognostic factors and therapy in 53 patients. J Surg Oncol. 2002;80:111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rohatainer A. Report on a workshop convened to discuss the pathological and staging classification of gastrointestinal tract lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 1994;5:397–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Jong D, Boot H, Van Heerde P, et al. Histological grading in gastric lymphoma and clinical relevance. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1461–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]