Abstract

Objective:

Esophagectomy for esophageal cancer is associated with substantial postoperative morbidity as a result of infectious complications. In a prior phase II study, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) was shown to improve leukocyte function and to reduce infection rates after esophagectomy. The aim of the current randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter phase III trial was to investigate the clinical efficacy of perioperative G-CSF administration in reducing infection and mortality after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer.

Patients and Methods:

One hundred fifty five patients with resectable esophageal cancer were randomly assigned to perioperative G-CSF at standard doses (77 patients) or placebo (76 patients), administered from 2 days before until day 7 after esophagectomy. The G-CSF and placebo groups were comparable as regards age, gender, risk, cancer stage, frequency of neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy, and type of esophagectomy (transthoracic or transhiatal esophageal resection).

Results:

Of 155 randomized patients, 153 were eligible for the intention-to-treat analysis. The rate of infection occurring within the first 10 days after esophagectomy was 43.4% (confidence interval 32.8–55.9%) in the placebo and 44.2% (confidence interval 32.1–55.3%) in the G-CSF group (P = 0.927). 30-day mortality amounted to 5.2% in the G-CSF group versus 5.3% in the placebo group (P = 0.985). Similar results were found in the per-protocol analysis.

Conclusion:

Perioperative administration of G-CSF failed to reduce postoperative morbidity, infection rate, or mortality in patients with esophageal cancer who underwent esophagectomy.

In this current randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter phase III trial the clinical efficacy of perioperative granulocyte colony-stimulating factor administration in reducing infection and mortality after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer was investigated. Perioperative administration of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor failed to reduce postoperative morbidity, infection rate or mortality in patients with esophageal cancer who underwent esophagectomy.

Despite improved surgical techniques and better perioperative management, postoperative complications remain a serious problem in patients undergoing esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. During the early postoperative course, infections occur in approximately 50% of patients,1–4 the majority of which relate to the lung. In larger series, pneumonia-associated postoperative mortality ranges between 5% and 10%.5–7 Possible reasons are the major surgical trauma, poor nutritional status, and reduced immune response. Impaired neutrophil function in patients with esophageal cancer has been reported as an additional putative cofactor for bacterial infections.8

Endogenous hematopoietic growth factors such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) enhance host defense against pathogens by mobilizing granulocytes and improving neutrophil function.9 In a recently published meta-analysis, G-CSF was shown to reduce the frequency and length of neutropenia in patients undergoing chemotherapy for malignant lymphoma10 and solid tumors.11 Currently, G-CSF is mainly used for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and neutropenia-associated infections, in clinical trials aimed at dose escalation of cytostatic drugs, as well as in high-dose chemotherapy and stem-cell selection. More recently, smaller studies have investigated the use of G-CSF to prevent bacterial infections in non-neutropenic patients.12–18 In a trial involving non-neutropenic postoperative/posttraumatic patients at high risk of sepsis, none of the G-CSF treated patients developed sepsis, whereas 3 patients in the control group died.14 Another trial involving patients with acute traumatic brain injury or cerebral hemorrhage reported that G-CSF was associated with a dose-dependent reduction in the frequency of bacteremia.15 One pilot study investigated the efficacy of G-CSF in preventing postoperative infections after radical vulvectomy.18 Compared with historic controls, the incidence of wound infection and wound breakdown was markedly decreased. Administration of G-CSF in these trials was safe and well tolerated. In addition, there is some evidence that G-CSF activates anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1ra and soluble TNF-alpha-receptor (sTNFR) and reduces the levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF).19

Because G-CSF might improve impaired neutrophil function in patients undergoing esophagectomy for esophageal cancer, our group performed a phase-II study using a perioperative application schedule.20 We found a marked increase in neutrophil function despite the extensive surgical trauma as well as a low infection rate in 20 patients enrolled when compared with historic controls.

To validate these data, we initiated a prospective placebo-controlled study with perioperative administration of G-CSF to reduce infection rates in patients after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Here, we report the results of this multicenter trial in a total of 155 randomized patients.

METHODS

Patients

From July 1997 to August 2001, eligible patients were enrolled in this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving 5 centers in Germany.

Selection Criteria

Patients were eligible for the trial if they had resectable esophageal cancer (Union Internationale Contre le Cancer [UICC] stage I–III), no distant metastases, and were free of infection. General health status had to be at least Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status grade 2.21 Patients older than 75 or younger than 18 years of age were not eligible. Patients were also excluded if they were immunocompromised (leuopenia <2 × 109/L, thrombocytopenia <100 × 109/L, known HIV infection, current myelosuppressive therapy), were undergoing concurrent therapy with other cytokines, were breast feeding or pregnant, had a known allergy against E. coli or its products, heart failure (New York Heart Association class III–IV), concurrent second malignancies, or were participating in other clinical trials.

Patients who had undergone preceding neoadjuvant therapy for esophageal cancer were eligible. Neoadjuvant therapy consisted of 36 Gy radiotherapy and 5-flurouracil/cis-diamminedichloroplatinum chemotherapy. Neoadjuvant therapy had to be terminated at least 2 weeks before surgery.

Treatment Assignment

Patients were randomly assigned to receive either filgrastim (rhG-CSF, Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA) or placebo (0.9% saline). Block randomization stratified according to site and preoperative risk was used. All assignments were made through a central randomization center 3 days before surgery. Filgrastim was used at a dose of 300 μg in patients below 75 kg body weight and 480 μg if body weight exceeded 75 kg. Analogous saline dose was given at a volume of 1 mL or 1.6 mL, respectively. Patients, physicians, and investigators were unaware of the treatment assignments.

Treatment started 2 days before esophagectomy with daily subcutaneous injections of the study drug and terminated on day 7 after surgery. If the white blood cell count (WBC) exceeded 75 × 109/L, study drug administration was discontinued until a WBC count of 37 × 109/L was reached. Administration of the study drug was also stopped upon diagnosis of infection requiring antibiotic treatment or occurrence of other serious adverse events. The safety profile, including physical examination, hematological and biochemical assessments, was evaluated daily during the first 30 postoperative days.

Definition of Infections

The diagnosis of pneumonia was based on clinical signs (ie, productive cough, dyspnoe, rales, and pleuritic chest pain, tachycardia, fever >39°C) and at least 1 of the following: presence of infiltrates on chest radiograph, positive culture of bronchoalveolar lavage, or blood. Mediastinitis was diagnosed if confirmed by rethoracotomy. Sepsis was defined according to Elebute and Stoner22 as tachycardia, hypotension, peripheral hypothermia, lactic acidosis, and hypoxemia. Urinary tract infection was assumed if the pathogen could be identified and if the patient showed clinical signs of urinary tract infection. Infections were categorized as early (≤ day 10 after surgery) or late events (> day 10 after surgery) until discharge or death.

Preoperative Risk Score

Patients were stratified according to a modified preoperative risk profile (23). Function of vital organs (eg, lung, heart, liver, and kidney), medical history, and performance status were included in this score. This risk score allowed stratification of patients into low- (score ≤ 16), medium- (17–22), and high-risk (score ≥ 23).

Surgery

Esophageal resection was performed either as transthoracic en-bloc esophagectomy via an abdomino-right thoracic approach (squamous cell or adenocarcinoma), transhiatal resection via an abdomino-left-cervical approach (distal adenocarcinoma), or cervical esophagectomy from a left cervical approach with upper sternotomy (cervical carcinoma) as described elsewhere.23 Reconstruction included gastric tube interposition with high intrathoracic or cervical esophagogastrostomy or colon interposition with cervical anastomosis. After cervical esophageal resection, reconstruction was performed by free jejunal interposition with microvascular arterial and venous anastomoses to vessels in the neck. Some patients with high risk-score profile had only transthoracic esophagectomy with closure of the cardia and cervical esophageal stoma placement without immediate reconstruction. Reconstruction was then performed in a second step 3–4 weeks later. Analysis of these patients only comprised the first step of esophagectomy and not the reconstruction procedure. Surgical procedures were standardized between the participating centers. Surgeons were permitted to switch to total gastrectomy with distal esophageal resection and esophagojejunal anastomosis if necessary. The patients in question were excluded from the per-protocol analysis. Antibiotic prophylaxis with cefazolin (2 × 2 g) and metronidazole (2 × 0.5 g) was given at the start of surgery and 8 hours later.

Ethics

The institutional ethic committees approved the protocol and written consent was obtained from all participants. The study was conducted according to the principals as stipulated in the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 1996.

Statistics

The primary efficacy end point was infection occurring within 10 days after surgery. Patients were analyzed both on an intention-to-treat as well as on a per-protocol basis. To be included in the per-protocol analysis, patients had to undergo esophagectomy for esophageal cancer, had to receive at least 4 applications of study drug, no additional antibiotic treatment without signs of infection, and a complete follow-up.

The trial was initially designed to enroll a total of 116 patients, allowing the detection of a 20% difference in infection rates between the G-CSF group and the placebo group with a power of 80% (α = 5% one-sided). The biometric assumptions were based on the results of a previous phase-II study.20 The trial was planned according to the 2-stage Bauer and Köhne adaptive method,24,25 which combines the 2 P values of the separate stages with Fisher's combination test. The first interim analysis was conducted after 58 patients had been treated per protocol. The sample size was recalculated on the basis of the interim result. Furthermore, the recursive testing principle26 was introduced, allowing an additional interim analysis. The second interim analysis was planned after a total of 130 patients had been treated.

Data were analyzed according to a prospectively defined plan. The primary analysis was based on a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test, in which the groups were stratified on the basis of 2 covariates: study center and preoperative risk. Two-sided P values for the primary end point were calculated using the logit-adjusted method. Unadjusted rates are provided together with their exact 95% confidence intervals. G-CSF and white blood cell count are given as average and 95% confidence intervals, and corresponding t-tests were calculated.

RESULTS

At the time of the second interim analysis, data from 155 randomized patients were available. Enrollment was suspended because the P value for the difference in infections rates after 10 days (main end point) exceeded the a priori threshold for stopping the trial for futility.

Baseline Characteristics of the Patients

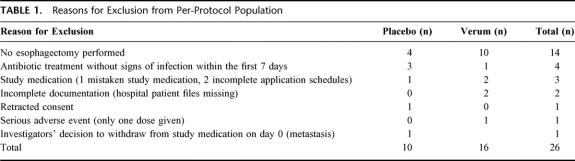

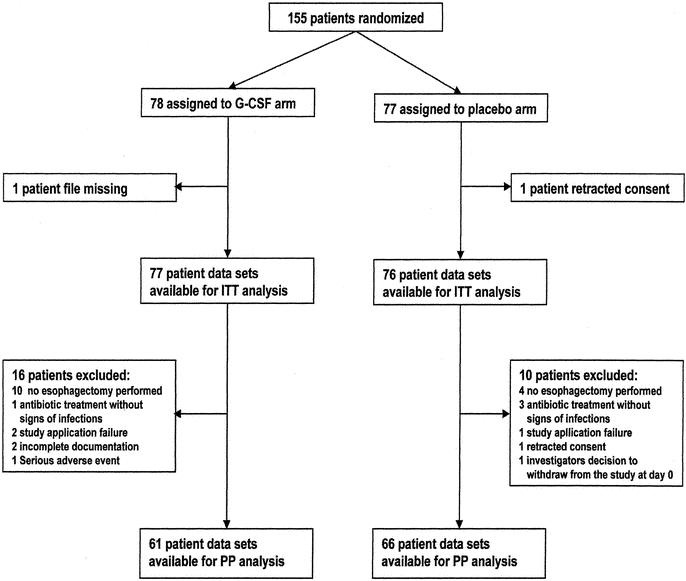

Of 155 initially randomized patients, 153 were eligible for the intention-to-treat analysis. Exclusions from this analysis were based on retracted informed consent (n = 1) and patient files missing (n = 1). A total of 26 patients were additionally excluded from the per-protocol analysis (16 in the G-CSF arm and 10 in placebo arm). Fourteen of these patients did not undergo esophagectomy for various reasons (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

TABLE 1. Reasons for Exclusion from Per-Protocol Population

FIGURE 1. Participant flow

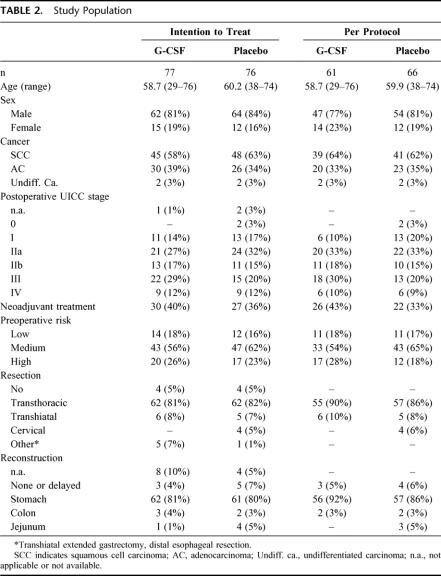

The patient characteristics were very similar in the placebo group and the G-CSF group, both in the intention-to-treat and the per-protocol population (Table 2). Median age of the 153 patients was 59.6 years (range 29–76 years), 82.4% of the patients were male. Squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma were the most common histology (60.8% and 36.6% respectively). Four patients (3%) had undifferentiated carcinomas. Most of the patients were suffering from advanced cancer (UICC stage II-IV) and only 15.7% had UICC stage I. Twelve percent had distant metastases, including celiac trunk lymph nodes not detected during the preoperative staging procedure. Neoadjuvant therapy had been performed in more than one-third of the patients clinically staged T3N+M0. This procedure resulted in complete pathologic regression (stage Py0) in 2 patients. Preoperative risk assessment showed high risk in 24.2% of the patients, medium risk in 58.8% and low risk in 17%. In 81% of the patients, transthoracic esophagectomy was performed. Transhiatal or cervical resection was less common (8% and 3% respectively). In 8 patients, the surgeon decided not to perform a resection (5%) or to remove the tumor by total gastrectomy with distal esophageal resection (4%). For reconstruction, stomach was used whenever applicable (81%). In 8 patients (5%), reconstruction after esophagectomy was delayed (n = 7) or was not performed (n = 1).

TABLE 2. Study Population

Laboratory Parameters

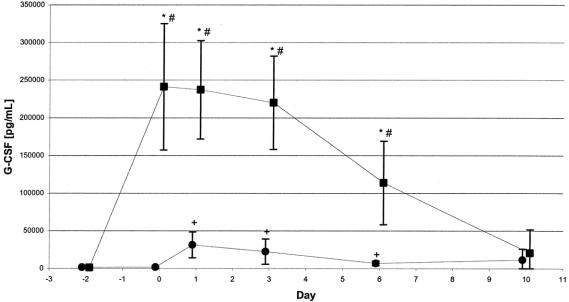

Although G-CSF serum concentrations were significantly elevated in the placebo group from day 1 to day 6 compared with day 2, G-CSF levels in the G-CSF group exceeded these levels by far. However, after day 6, G-CSF levels markedly decreased in the G-CSF group. Differences between the means in the G-CSF and the placebo groups were significant from day 0 through day 6 (Fig. 2). The maximum G-CSF level was 241 ng/mL in the G-CSF compared with 31.5 ng/mL in the placebo group.

FIGURE 2. G-CSF serum levels in ITT population. G-CSF serum levels increased significantly in both groups within the first few postoperative days. Mean maximum G-CSF serum concentration in the G-CSF group (n = 35–46) exceeded by far the maximum level in the placebo group (n = 22–34; 241 ng/mL vs. 31.5 ng/mL). Values are given as means with their corresponding 0.95 confidence intervals. ▪, G-CSF; •, placebo, *P ≤ 0.05 for difference between both groups, #P ≤ 0.05 for difference within the G-CSF group compared with day-2, +P ≤ 0.05 for difference within the placebo group compared with day-2.

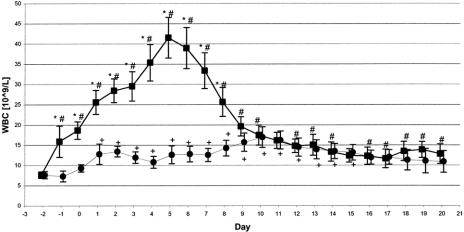

Similarly, mean WBC increased in the G-CSF group until day 6, with a peak of 41 × 109/L. In the placebo group, maximum mean WBC was 17 × 109/L on day 10. Compared with day 2, mean WBC was significantly increased on day 1 through day 20 in the G-CSF and day 1 through day 13 in the placebo group. Differences in mean WBC between both groups were significant on day 1 through day 8 (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3. WBC count in ITT population. WBC counts increased significantly in both groups within the first few postoperative days. However, maximum leukocyte counts in the G-CSF group (n = 27–71) exceeded by far the maximum level in the placebo group (n = 16–69; 41.5*109/L versus 17*109/L). Values are given as means with their corresponding 0.95 confidence intervals. ▪, G-CSF; •, placebo, *P ≤ 0.05 for difference between both groups, #P ≤ 0.05 for difference within the G-CSF group compared with day-2, +P ≤ 0.05 for difference within the placebo group compared with day-2.

Safety

A total of 26 serious adverse events occurred (12 in the G-CSF group, 14 in the placebo group). Death due to infection was the most common serious adverse event in both groups (8 patients in the G-CSF, 6 in the placebo group). Pulmonary embolism, myocardial ischemia, cardiac arrest, necrosis of the interposed colon and deep venous thrombosis were equally distributed (4 in G-CSF, 3 in placebo group).

Efficacy of Anti-infective Prophylaxis

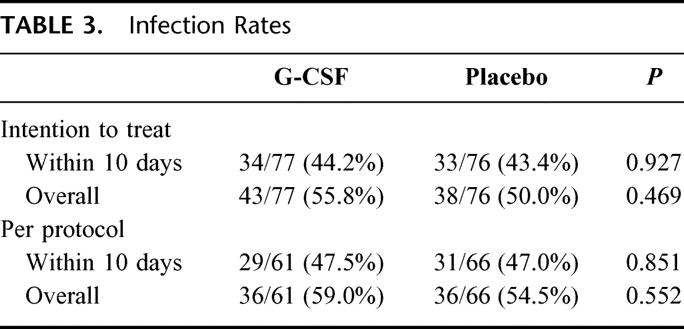

The major end point of this study was infection rate within 10 days after attempted esophagectomy. In the 153 patients evaluable, a total of 67 (43.8%) contracted infections during the first 10 days and 81 (52.9%) overall. As shown in Table 3, there were no significant differences in the 10-day infection rate or the overall infection rate between the G-CSF and placebo groups. These findings were observed in both the intention-to-treat and the per-protocol analysis.

TABLE 3. Infection Rates

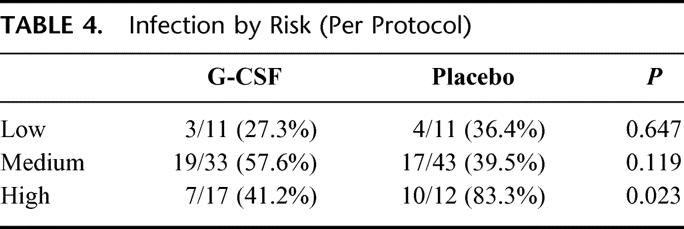

Subgroup analysis was performed according to a preoperative risk score. Infectious complications were significantly more frequent in patients with high preoperative risk (63.9%) as compared with patients having low (38.5%) or medium risk (52.8%; P for trend = 0.049). In high-risk patients, the overall infection rate was 60.0% in the G-CSF and 68.8% in the placebo group (P = 0.601). However, as shown in Table 4, the per-protocol population with high risk showed a significant difference in infections within 10 days after surgery between the G-CSF group (7/17, 41.2%) and the placebo group (10/12, 83.3%, P = 0.023).

TABLE 4. Infection by Risk (Per Protocol)

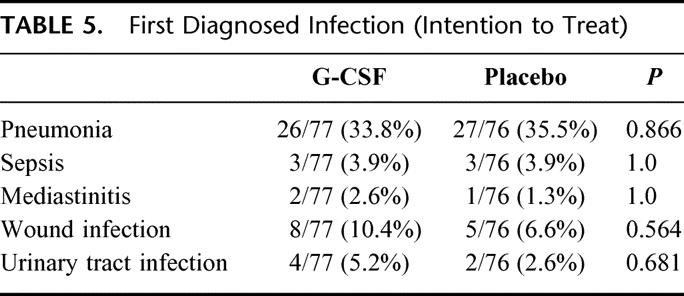

There were no major differences in the type of first diagnosed infection between the 2 groups (Table 5). Pneumonia was the major infectious complication diagnosed (34.6%). Serious wound infections occurred in 8.5% of the patients. Infectious complications in patients with cervical anastomosis (21/77 in the verum group, 20/76 in the placebo group) was slightly more frequent than in other patients: 51.2% (21/41) in patients with cervical anastomosis versus 41.1% (46/112) in other patients, P = 0.276). Overall, infections occurred earlier in the placebo group (day 4, range 1–27) than in the G-CSF group (day 6, range 0–75, P = 0.234; data not shown).

TABLE 5. First Diagnosed Infection (Intention to Treat)

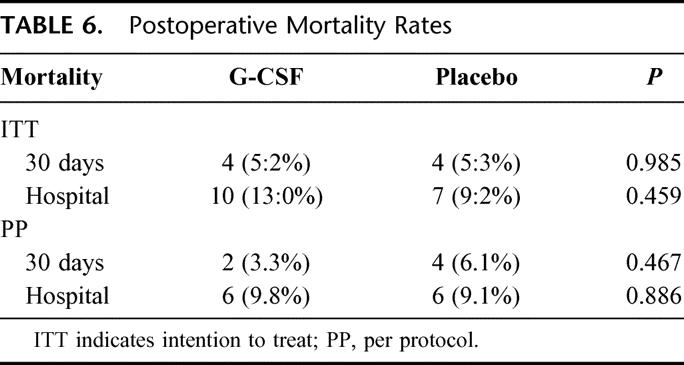

Thirty-day and hospital mortality were not significantly different between the G-CSF and placebo groups, neither in the intention-to-treat nor in the per-protocol analysis (Table 6). Of the fatal outcomes, 88.2% occurred in patients who contracted infections within the first 10 days following surgery.

TABLE 6. Postoperative Mortality Rates

Because 8 patients of the ITT population did not receive simultaneous reconstructive surgery (3 in the G-CSF, 5 in the placebo group) we analyzed whether this affects infection rate. Within the first 10 days 2 out of 8 (25.0%) patients without, but 63 out of 131 (48.1%) patients with, simultaneous reconstructive surgery developed infections (P = 0.283).

DISCUSSION

This is the first placebo-controlled, randomized study to evaluate the impact of G-CSF-stimulated neutrophil function in non-neutropenic patients undergoing major surgery. Esophagectomy in patients with esophageal cancer was chosen due to the substantial inherent postoperative mortality. The aim of this study was to reduce the infection rate after esophagectomy by means of a perioperative administration schedule in which G-CSF was given from 2 days before and up to 7 days after surgery.

The findings to emerge from this study are: (1) G-CSF is safe in patients with esophageal cancer undergoing esophagectomy. (2) The number of leukocytes and G-CSF peak levels were significantly higher in the G-CSF-treated patients (Figs. 2 and 3). (3) There was no significant difference in the postoperative infection rate within 10 days after surgery between G-CSF or placebo-treated patients on the basis of an intention-to-treat analysis (44.2% versus 43.4%, P = 0.927). Similar results were found for the per-protocol analysis (47.5% versus 47.1%, P = 0.851). (4) There were also no significant differences in other clinical parameters such as the type of infection or overall hospital mortality.

There were several lines of evidence warranting a randomized study in which G-CSF was evaluated for its potential to prevent infection in patients with esophageal cancer undergoing esophagectomy. These comprise the substantial risk of postoperative infection,1–4 the reported defect in neutrophil response in these patients8 and earlier data from a nonrandomized study suggesting that perioperative treatment with G-CSF in this setting might indeed be effective.20 To this end, we were able to show that treatment with G-CSF starting 2 days prior to the planned esophagectomy significantly increases the number of neutrophils. However, other parameters, including the phagocytic activity and oxidative burst of granulocytes, and a variety of cytokines such as ICAM-1, IL-1ra, TNF-alpha, sTNFRp55, sTNFRp75 and IL-6, did not differ significantly between both groups (data not shown).

This multicenter trial was conducted in large cancer centers and general hospitals with substantial experience in the surgery of esophageal cancer. Thus the 30-day mortality rate of 5.2% represents the actual quality of surgery for esophageal cancer and is in accordance with published mortality rates.7

The reasons for the development of infectious complications after esophagectomy are varied. Pulmonary complications are mainly related to the surgical trauma, which mostly combines a thoracotomy and laparotomy in patients with pre-existing pulmonary disease.5 Surgical complications such as anastomotic leakage occur in 10% to 30% of patients and are followed by severe systemic infections, eg, sepsis or mediastinitis.27

In the present study, 77.6% of infections occurred within the first 5 days after surgery. During this period, leukocytes were sufficiently stimulated both in number and function in the G-CSF-treated group. Since the peak leukocyte count (41.5×109/L) was reached at day 5 postoperatively, it cannot be excluded that earlier commencement of preoperative G-CSF administration might have resulted in even greater stimulation of granulopoiesis, thus possibly leading to more effective neutrophil stimulation. In the high-risk group, we found a therapeutic benefit for the G-CSF-treated patients with respect to the primary study end point. However, trend analysis could not identify a significant association between preoperative risk and infection rate with G-CSF application. In a previous phase-II study with a high-risk population (septic patients, APACHE II score > 25), G-CSF treatment was demonstrated to be efficacious. Filgrastim-treated patients had lower mortality rates and early reversal of shock.14

Only 2 randomized controlled studies demonstrated a significantly improved outcome for foot infections in diabetic patients treated with G-CSF.28,29 Foot amputation rates and administration of antibiotics were reduced. Both studies suffer from small patient numbers (40 patients) and are monocenter trials. A randomized study in 61 patients with acute traumatic brain injury and cerebral hemorrhage showed a significant decrease in bacteremia in those prophylactically treated with G-CSF.15 However, there was no obvious clinical effect on the frequency of nosocomial pneumonia or urogenital infection rates. In another study, G-CSF was used as an additive to antibiotics in 756 hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia. G-CSF in combination with antibiotics had no influence on the length of recovery from pneumonia or the mortality rate compared with standard antibiotics. However, the incidence of systemic and local complications of sepsis such as organ dysfunction (acute respiratory distress syndrome, acute renal failure, shock and disseminated intravascular coagulation) was significantly reduced.12 To verify this observation, the same authors conducted a large randomized study, which included 480 patients with multilobar pneumonia.13 There was no difference in any of the primary efficacy endpoints (adult respiratory distress syndrome, acute renal failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation, shock, empyema or death from any cause) or secondary endpoints including 28-day mortality, number of days in the intensive care unit or time to resolution of infiltrates during treatment with G-CSF or placebo in combination with standard antibiotic therapy.

A recent comprehensive meta-analysis in patients with malignant lymphoma receiving chemotherapy at standard doses indicated that the number of infection-related mortalities is not significantly influenced by the application of G-CSF in this setting.10 Thus G-CSF may be limited to the prevention of minor infections such as neutropenic fever.

In summary, this study shows that the prophylactic administration of G-CSF in surgical patients at high risk of developing infectious complications does not reduce infection rates.

Footnotes

Supported by the German Cancer Society (Grant-No. 70-2308-En4) and Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, California.

Reprints: A. H. Hoelscher, MD, Professor of Surgery, Department of Visceral and Vascular Surgery, University of Cologne, Joseph-Stelzmann-Str. 9, 50931 Cologne, Germany. E-mail: Arnulf.Hoelscher@medizin.uni-koeln.de.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ferguson MK, Martin TR, Reeder LB, et al. Mortality after esophagectomy: risk factor analysis. World J Surg. 1997;21:599–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fang W, Igaki H, Tachimori Y, et al. Three-field lymphe node dissection for esophageal cancer in elderly patients over 70 years of age. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:867–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rindani R, Martin CJ, Cox MR. Transhiatal versus Ivor-Lewis oesophagectomy: is there a difference? Aust N Z J Surg. 1999;69:187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolh P, Honoré P, Gielen JL, et al. Étude de mortalité et de morbidité üériopératoires. Rev Med Liege. 1998;53:187–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan ST, Lau WY, Yip WC, et al. Prediction of postoperative pulmonary complications in oesophagogastric. Br J Surg. 1987;74:408–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishi M, Hiramatsu Y, Hioki K, et al. Pulmonary complications after subtotal oesophagectomy. Br J Surg. 1988;75:527–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Lanschot JJB, Hulscher JBF, Buskens CJ, et al. Hospital volume and hospital mortality for esophagectomy. Cancer. 2001;91:1574–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saito T, Shigemitsu Y, Kinoshita T, et al. Impaired neutrophil bactericidal activity correlates with the infection occuring after surgery for esophageal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1992;51:159–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollmächer T, Korth C, Schreiber W, et al. Effects of repeated administration of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) on neutrophil counts, plasma cytokine and cytokine receptor levels. Cytokine. 1996;8:799–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bohlius J, Reiser M, Engert A, et al. Granulopoiesis-stimulating factors in the prevention of adverse effects in the chemotherapeutic treatment of malignant lymphoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;4:CD003189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyman GH, Kuderer NM, Djulbegovic B. Prophylactic granulocyte colony stimulating factor in patients receiving dose-intensive cancer chemotherapy: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2002;112:406–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nelson S, Belknap SM, Carlson RW, et al. A randomized controlled trial of filgrastim as an adjunct to antibiotics for treatment of hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1075–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson S, Heyder AM, Stone J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of filgrastim for the treatment of hospitalized patients with multilobar pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:970–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wunderink RG, Leeper KV, Schein R, et al. Filgrastim in patients with pneumonia and severe sepsis or septic shock. Chest. 2001;119:523–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heard SO, Fink MP, Gamelli RL, et al. Effect of prophylactic administration of recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (filgrastim) on the frequency of nosocomial infections in patients with acute traumatic brain injury or cerebral hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:748–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pettilä V, Takkunen O, Varpula TMA, et al. Safety of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (filgrastim) in intubated patients in the intensive care unit: interim analysis of a prospective, placebo-controlled, double blind study. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3620–3625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiss M, Gross-Wege W, Harms B, et al. Filgrastim (rhG-CSF) related modulation of the inflammatory response in patients at risk of sepsis or sepsis. Cytokine. 1996;8:260–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Lindert AC, Symons EA, Damen BF, et al. Wound healing after radical vulvectomy and inguino-femoral lymphadenectomy: experience with granulocyte colony stimulating factor (filgrastim, r-metHuG-CSF). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1995;62:217–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartung T. Immunomodulation by colony-stimulating factors. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;136:6–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schäfer H, Hübel K, Bohlen H, et al. Perioperative treatment with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) in patients with esophageal cancer stimulates granulocyte function and reduces infectious complications after esophagectomy. Ann Hematol. 2000;79:143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elbute EA, Stoner HB. The grading of sepsis. Br J Surg. 1983;70:29–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hölscher AH, Bollschweiler E, Bumm R, et al. Prognostic factors of resected adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Surgery. 1995;118:845–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bauer P, Köhne K. Evaluation of experiments with adaptive interim analysis. Biometrics. 1994;50:1029–1041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wassmer G, Eisebitt R, Coburger S. Flexible interim analyses in clinical trials using multistage adaptive test designs. Drug Information J. 2001;35:1131–1146. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brannath W, Posch M, Bauer P. Recursive combination tests. J Am Stat Ass. 2002;97:236–244. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsutsui S, Moriguchi S, Morita M, et al. Mulitvariate analysis of postoperative complications after esophageal resection. Ann Thorac Surg. 1992;53:1052–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gough A, Clapperton M, Rolando N, et al. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor in diabetic foot infection. Lancet. 1997;350:855–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Lalla F, Pellizzer G, Strazzabosco M. Randomized prospective controlled trial of recombinant granulocyte colony-stimulating factor as adjunctive therapy for limb-threatening diabetic foot infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:1094–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]