Abstract

Objective:

We sought to determine the influence of thermal (burn) injury with sepsis and norepinephrine on the clonogenic potential and functional cytokine response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation in nonmyeloid committed (CD117+) and myeloid committed (ER-MP12+) bone marrow progenitor cells.

Summary and Background Data:

We have previously demonstrated that norepinephrine stimulated myelopoiesis after burn injury and sepsis, but the site of this stimulation in monocyte development is unknown. In the present study the influence of norepinephrine on the developmental hierarchy of bone marrow cells after thermal injury and sepsis was determined by assessing the clonogenic potential and LPS-stimulated cytokine responses of mature macrophages derived from CD117+ and ER-MP12+ bone marrow progenitor cells.

Methods:

Tissue and bone marrow norepinephrine content was ablated by chemical sympathectomy with 6-hydroxydopamine treatment. CD117+ and ER-MP12+ bone marrow cells were isolated using antibody-linked magnetic microbeads. Clonogenic potential in response to colony-stimulating factors was determined. Both progenitor cell types were differentiated to mature macrophages in vitro and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-6 cytokine responses to LPS provocation were determined.

Results:

The macrophage- and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor responsive clonogenic potential was increased with burn sepsis, suggesting an expansion of both progenitor populations. Such increases were greatly reduced with prior depletion of norepinephrine. TNF-α and IL-6 cytokine responses to LPS were markedly influenced by the specific progenitor cells involved as well as the injury conditions and the status of norepinephrine prior to injury. In burn sepsis the depletion of norepinephrine resulted in a dramatic decrease in both IL-6 and TNF-α production by both progenitor-derived macrophages.

Conclusions:

Depletion of norepinephrine attenuated burn and burn sepsis-induced bone marrow progenitor clonal growth in response to macrophage- and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Functional phenotypes of bone marrow progenitor-derived macrophages are greatly influenced by norepinephrine and the milieu created by thermal injury and sepsis.

Norepinephrine depletion ameliorated burn injury and sepsis-induced enhancement in M-colony-stimulating factors and GM-colony-stimulating factors responsive clonogenic potential of CD117+ and ER-MP12+ bone marrow progenitors. When these progenitors were differentiated into macrophages, norepinephrine modulated LPS-stimulated cytokine production in a lineage and injury specific manner. Norepinephrine appears to be a potent modulator of monocyte production and function.

Despite significant advances in the recognition, monitoring, and treatment of severely injured patients during the last 20 years, sepsis remains the major cause of morbidity and mortality among those who survive their initial insult.1 Critically injured patients surviving severe trauma undergo immune dysregulation and a profound inflammatory response,2–4 and in many instances such patients develop the systemic inflammatory response syndrome, septic shock, and multiple organ failure.5

As in many life-threatening situations, conditions related to shock and sepsis are accompanied by a profound sympathetic response involving the release of epinephrine from the adrenal medulla and norepinephrine from peripheral nerve terminals. Although sympathetic activation is typically viewed as a compensatory response for cardiovascular and metabolic systems, we have previously shown that increased release of bone marrow norepinephrine may exacerbate the conditions of sepsis.6,7 Our previous work also suggests that peripheral monocytosis and bone marrow monocytopoiesis that occur as a result of burn trauma and sepsis are associated with increased release of bone marrow norepinephrine6 and that reductions in bone marrow norepinephrine before burn sepsis reduce monocyte expansion and significantly enhance survival. Because monocyte and macrophage triggered inflammation, which is a constituent part of sepsis,8,9 is characterized by the early onset of proinflammatory cytokine release followed later by the dominance of anti-inflammatory cytokines that may contribute to conditions of immuno-suppression,3,4 bone marrow sympathetic stimulation may play an important role in the pathophysiology of sepsis.

There is considerable evidence that catecholamine stimulation can mediate macrophage cytokine responses and such findings include tissue specific as well as circulating monocyte-derived macrophages (as reviewed by Bergmann10). For example, both peritoneal macrophages and Kupfer cells respond to stimulation with norepinephrine by increasing production of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α,11,12 suggesting that acute increase in catecholamines has the potential to modify cytokine release from macrophages. However, considering the involvement of norepinephrine in the expansion of monocytes and macrophages consequent to sepsis the more important question is how norepinephrine might influence monocyte development (ie, enhanced proliferation) and the phenotypic characteristics (cytokine response to lipopolysaccharide [LPS]) of these newly developed cells.

Pursuant to our interest in bone marrow adrenergic stimulation of myelopoiesis after thermal injury and sepsis we tested the affect of adrenergic stimulation with burn sepsis by reducing bone marrow exposure to endogenous adrenergic neurotransmitter. In doing this we examined the paracrine influence of endogenous bone marrow adrenergic neurotransmitters for their potential action on the development of monocytes. We used early bone marrow progenitors bearing the stem cell marker CD117 (c-kit)13 and a more committed monocyte progenitor ER-MP1214 to demonstrate and then to compare the expansion of both of these cellular compartments after burn and burn sepsis. Cytokine responses of mature macrophages derived from both progenitors were also examined. Our findings suggest that conditions within the bone marrow define the development of bone marrow progenitors into monocytes and macrophages and their cytokine production.

METHODS

Animals and Treatment Protocols

Animals

Adult male B6D2F1 mice (22–28 g, Jackson Labs, Barr Harbor, ME) were used in all experiments. Mice were housed in a central animal facility that maintained an environment of controlled temperature, relative humidity, and a 12-hour light–dark cycle. Animals were maintained in the controlled environment for at least 1 week before being used in experiments. All experimental protocols used in this study were approved by the Loyola University Medical Center Animal Care and Use Committee.

Thermal Injury and Infectious Challenge

Thermal injury was induced in mice as described by Walker and Mason.15 The animals were randomized into sham, burn, and burn sepsis groups, anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg), and the dorsal hair removed with clippers. Mice in the burn and burn sepsis groups were placed supine into a Delrin® template and subjected to a 15% full-thickness dorsal scald by partial immersion into a 100°C water bath for 7 seconds. Higher percentage burns resulted in unacceptable levels of mortality that severely limit the usefulness of the model. All 3 groups were resuscitated with 2 mL 0.9% NaCl intraperitoneally. Mice in the burn sepsis group were inoculated with 1000 CFU of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 19960, Rockville, MD) at the burn site immediately after the injury.

Treatment With 6-Hydroxydopamine

Mice were treated intraperitoneally with 100 mg/kg of 6-hydroxydopamine hydrochloride (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) in 0.5 mL of saline containing 0.1% ascorbic acid as an antioxidant. Mice were treated daily for 5 days consecutively and on day 7 were subjected to the thermal injury protocol. Treatment with 6-hydroxydopamine did not result in any animal mortality. This protocol is identical to that used previously in which there was an approximate 80% reduction in bone marrow norepinephrine content 72 hours after thermal injury.6

Preparation of Bone Marrow Cells

For assessment of bone marrow cell function, mice were euthanized at 72 hours after thermal injury. Total bone marrow cells from each femur pair were collected aseptically by eluting the medullary cavity with 3 mL of RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), Penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) using a 1-mL syringe and a 25-gauge needle. An aliquot of the cell suspension was diluted in 3% acetic acid to lyse red blood cells and the total nucleated cells were estimated using a Neubauer hemocytometer.

Separation, Culture, and LPS Stimulation of Bone Marrow Cells

Bone marrow cells were labeled with monoclonal antibodies to ER-MP12 and CD117 (Accurate Chemical Co., Westbury, NY), followed by microbead-conjugated secondary antibody. The antibody-labeled cells were run through a MiniMACS column surrounded by a magnet (Miltenyi Biotec. Inc., Auburn, CA) to isolate ER-MP12 and CD117 bone marrow cells. To obtain adequate numbers of specific bone marrow cells, total bone marrow cells from 2 to 5 mice were routinely pooled prior to magnetic bead separation. After removal of the magnet cells were eluted from the column and counted. Enriched cells (either ER-MP12+ or CD117+) were differentiated into macrophages in the presence of murine recombinant Flt-3 ligand, IL-3, and either macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) or granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF; all 10 ng/mL) for 7 days. All media and reagents were filtered through polysulfonate filters to remove traces of bacterial endotoxin. After the incubation period, the adherent cells were confirmed to be mature macrophages by CD14 and CD11b expression in 90% of all cells. Neither CD14 nor CD11b was present on freshly isolated CD117 or ER-MP12 cells (data not shown). On day 7 the adherent cells were washed and incubated in fresh RPMI-1640 media with 10% FCS with or without LPS (100 ng/mL, Escherichia coli, Difco, Detroit, MI) for 18 hours. Conditioned media were then collected and stored at −70°C until cytokine analysis. Total cellular protein was assayed by BCA protein assay reagent kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Cytokine Assay

TNF-α and IL-6 levels in the conditioned media were determined by standard ELISA techniques (Endogen, Woburn, MA). All cytokine concentrations are reported as pg/mg protein.

Soft-Agar Clonogenic Assay

The clonogenic potential of the bone marrow cells was determined as previously described.16–18 Clonal proliferation is a measure of bone marrow progenitor cells to respond to given combinations of growth factors by development of terminally differentiated cells. The growth of such colonies in this assay is a measure of the potential of bone marrow progenitor cells to proliferate and differentiate to a particular lineage in a growth factor-specific manner.

Total bone marrow cells (25,000 cells/well) were cultured in 1 mL of McCoy's medium containing 20% FCS, 0.3% Bacto agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI), penicillin (100 units/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL). The cultures were stimulated with rmIL-3 and rmFlt-3 ligand (10 ng/mL) in combination with either rmM-CSF, or rmGM-CSF (10 ng/mL). Control cultures were incubated in the absence of any CSF. All culture dishes in triplicate were incubated for 7 days at 37°C in a 10% CO2 atmosphere. Colonies with greater than 50 cells were then counted using a light microscope and the total number of colony-forming units (CFU) per 25,000 cells were reported.

Flow Cytometric Analysis

Bone marrow progenitor profile of CD117+ and CD34+ cells was determined by dual color flow cytometry. After blocking the Fc receptor with a rat antimouse CD16/CD32 (FcγIII/II) antibody (1 μg/106 cells; PharMingen, San Diego, CA) for 5 minutes at 4°C, bone marrow cells (1 × 106 cells) were labeled with Fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated CD117 (2 μL) and biotin-conjugated CD34 (4 μL; PharMingen, San Diego, CA) for 30 minutes at 4°C. The cells were then washed 3 times with normal phosphate-buffered saline, resuspended in 100 μL phosphate-buffered saline with 0.1% bovine serum albumin, and incubated with streptavidin phycoerythrin (5 μL; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 30 minutes at 4°C. At the end of this time, the cells were washed 3 times with phosphate-buffered saline and then fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde before cytometric analysis. Criteria for gating of fluorescent intensity was set on the basis of light scatter patterns of unstained total bone marrow cells.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons of more than 2 experimental groups were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance followed by Student–Newman–Keuls mean separation technique and this involved Figures 1 to 4. Comparison of 2 experimental groups were analyzed using a Student t test for unpaired data and this involved data analysis in Figures 5 and 6 (NE intact vs. NE depleted values for each injury treatment group). In all cases data are presented as mean values ± the standard error of the mean, significance implies P < 0.05 and the sample size (N value) refers to the number of repetitions of each experiment.

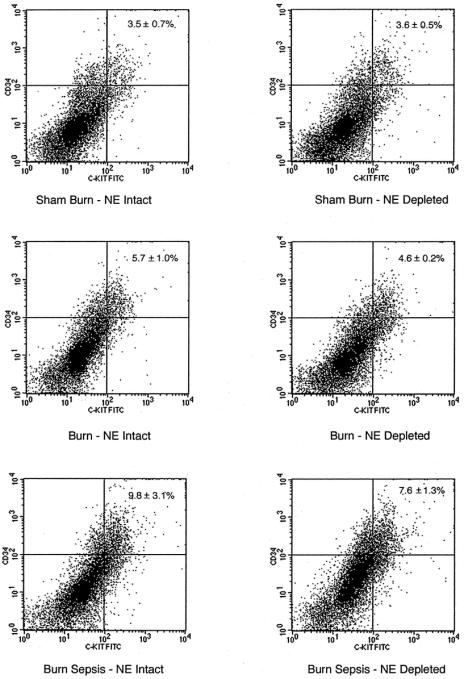

FIGURE 1. Dual-color flow cytometric analysis for the expression of CD34 and CD117 antigens on total nucleated bone marrow cells after sham, burn, and burn sepsis 72 hours after injury in norepinephrine-intact (NE intact) and norepinephrine-depleted (NE depleted) animals. X- and Y-axes represent fluorescent intensity in log scale. Each panel is representative of 4 animals in each group.

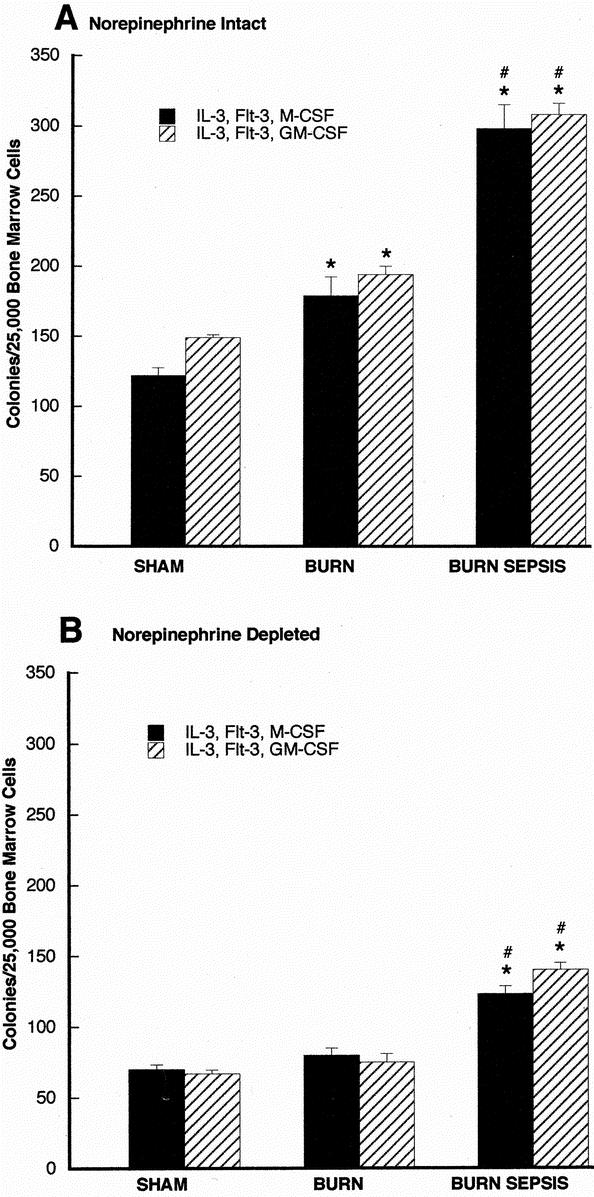

FIGURE 2. Soft agar clonogenic assay for CD117+ bone marrow progenitors 72 hours after sham, burn, and burn sepsis in norepinephrine intact (A) and norepinephrine depleted (B) animals. CD117+ cells (2.5 × 104 cells/mL) were incubated in RPMI media containing 0.3% agar in the presence of rmIL-3 and rmFlt3 with either rmGM-CSF or rmM-CSF (all at 10 ng/mL). Colonies (>50 cells) were counted with a light microscope after 7 days of incubation. All assays were done in triplicate and each bar represents results of 3 experiments (n = 3) involving 6–15 animals each. *P < 0.05 versus sham; #P < 0.05 versus burn.

FIGURE 3. Soft agar clonogenic assay for ER-MP12+ bone marrow progenitors 72 hours after sham, burn, and burn sepsis in norepinephrine intact (A) and norepinephrine depleted (B) animals. ER-MP12+ cells (2.5 × 104 cells/mL) were incubated in RPMI media containing 0.3% agar in the presence of rmIL-3 and rmFlt3 with either rmGM-CSF or rmM-CSF (all at 10 ng/mL). Colonies (>50 cells) were counted with a light microscope after 7 days of incubation. All assays were done in triplicate and each bar represents results of 3 experiments (n = 3) involving 6–15 animals each. *P < 0.05 versus sham; # P < 0.05 versus burn.

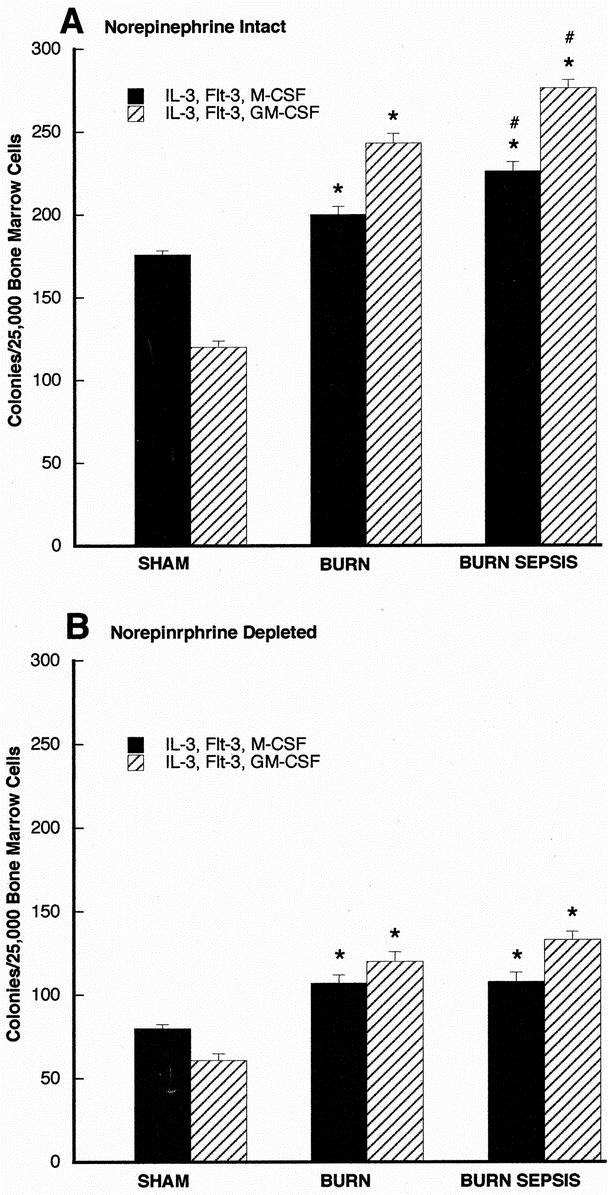

FIGURE 4. LPS-stimulated IL-6 production (A) and TNF-α production (B) in CD117+ and ER-MP12+ bone marrow progenitor-derived macrophage taken from animals with intact norepinephrine. Progenitor cells were isolated from sham, burn and burn sepsis mice and differentiated into macrophages with a cocktail of growth factors (rmFlt-3 Ligand, rmIL-3, rmM- and rmGM-CSF all 10 ng/ml) for 7 days at 37°C. Macrophages were stimulated with LPS (100ng/ml) for 18 hours and cytokines were measured in the supernatants and normalized to cellular protein concentration. All assays were done in triplicate and each bar represents results of 3 experiments (N=3) involving 6–15 animals each. *P < 0.05 versus sham; #P < 0.05 versus burn.

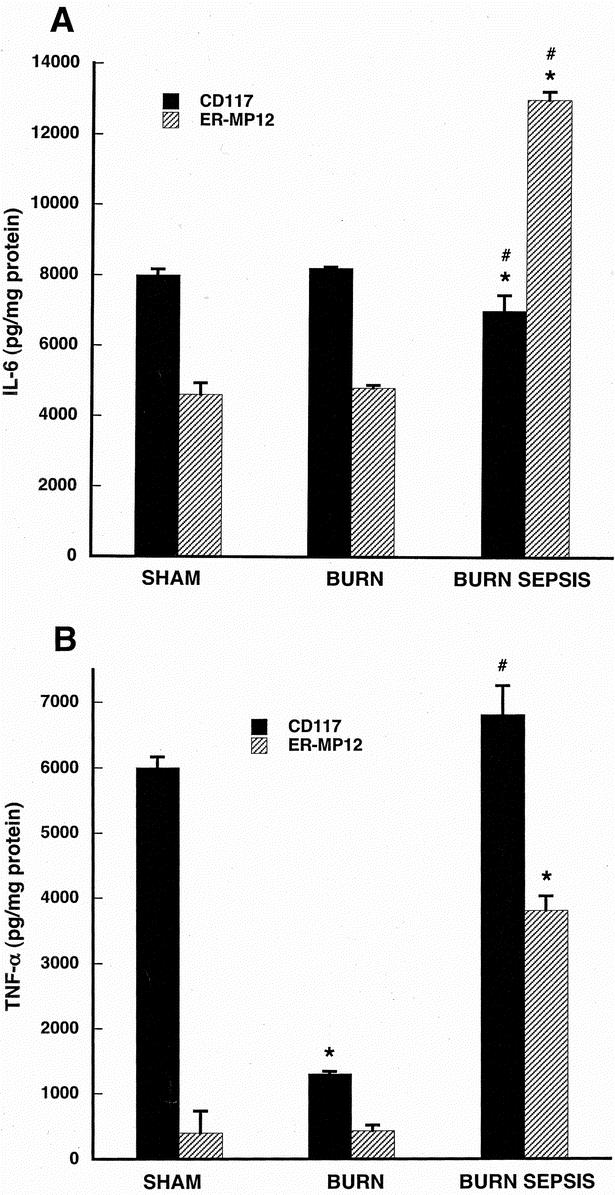

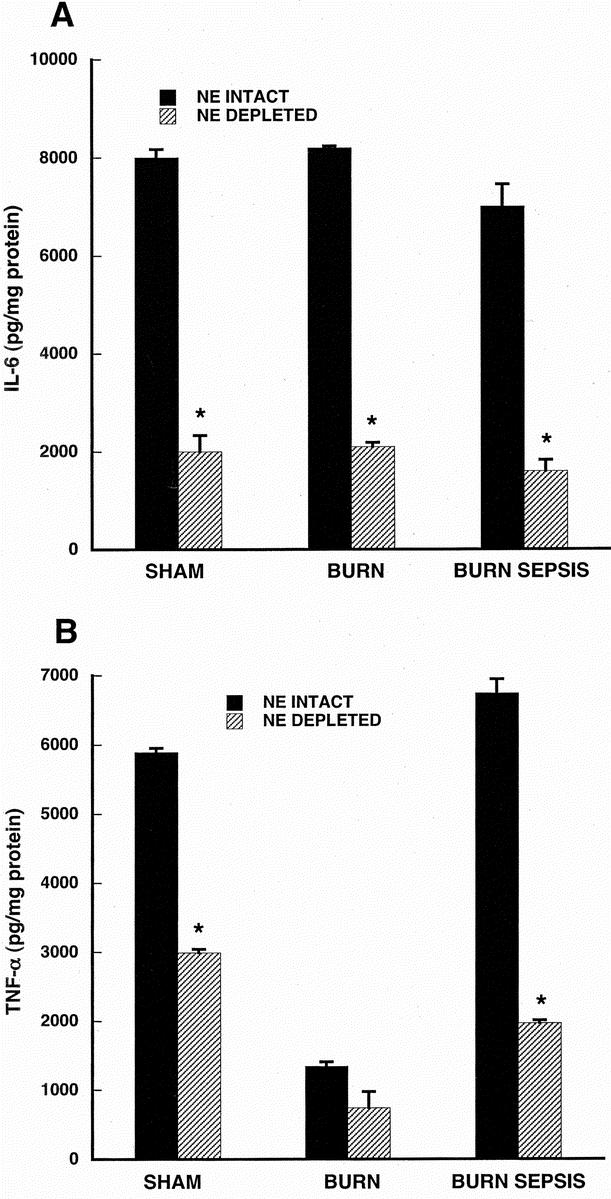

FIGURE 5. LPS-stimulated IL-6 production (A) and TNF-α production (B) in CD117+ bone marrow progenitor-derived macrophage taken from animals with and without norepinephrine depletion. Progenitor cells were isolated from sham, burn and burn sepsis mice with intact or depleted norepinephrine. CD117+ progenitors were differentiated into macrophages with a cocktail of growth factors (rmFlt-3 Ligand, rmIL-3, rmM- and rmGM-CSF all 10 ng/ml) for 7 days at 37°C. Macrophages were stimulated with LPS (100ng/ml) for 18 hours and cytokines were measured in the supernatants and normalized to cellular protein concentration. All assays were done in triplicate and each bar represents results of 3 experiments (n = 3) involving 6–15 animals each. *P < 0.05 versus NE intact.

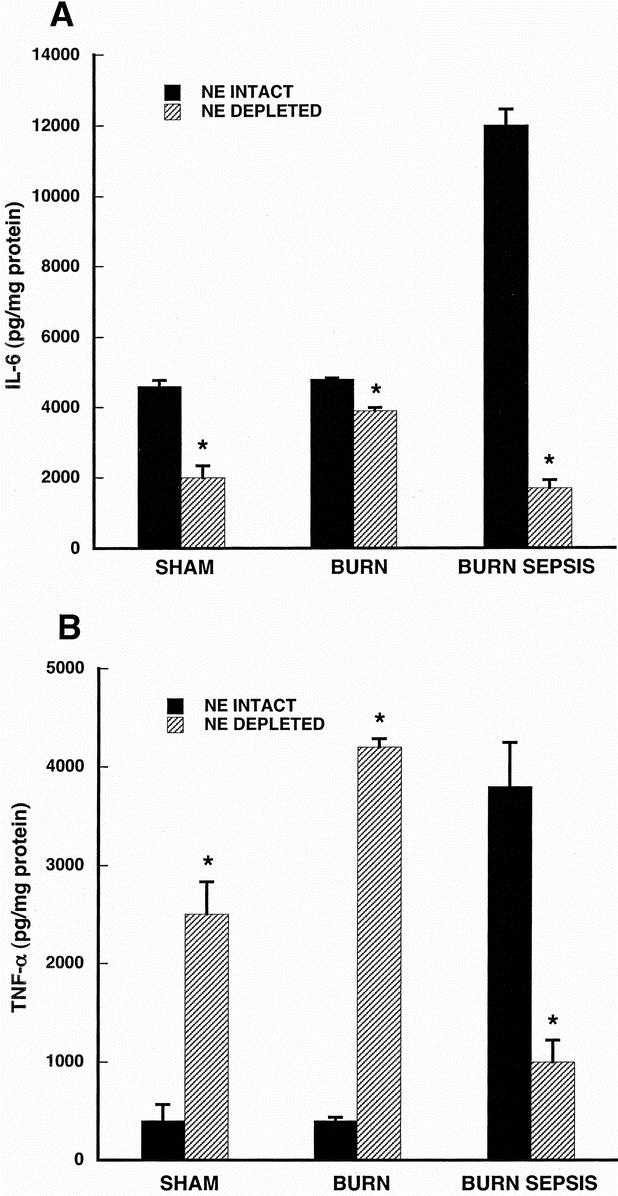

FIGURE 6. LPS-stimulated IL-6 production (A) and TNF-α production (B) in ER-MP12+ bone marrow progenitor-derived macrophage taken from animals with and without norepinephrine depletion. Progenitor cells were isolated from sham, burn and burn sepsis mice with intact or depleted norepinephrine. ER-MP12+ progenitors were differentiated into macrophages with a cocktail of growth factors (rmFlt-3 Ligand, rmIL-3, rmM- and rmGM-CSF all 10 ng/ml) for 7 days at 37°C. Macrophages were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 18 hours and cytokines were measured in the supernatants and normalized to cellular protein concentration. All assays were done in triplicate and each bar represents results of 3 experiments (n = 3) involving 6–15 animals each. *P < 0.05 versus NE intact.

RESULTS

Animal Mortality and Sepsis

Sham and burn treatment groups did not result in any mortality by 72 hours when all animals were euthanized. Burn sepsis animals had an approximate 30% mortality by 72 hours. Most mortality occurred between 48 and 72 hours. Establishment of sepsis through the systemic spread of Pseudomonas aeruginosa was determined by positive blood cultures19 but circulating levels of bacterial endotoxin were not determined. No apparent weight loss was evident and with food and water available ad libitum lack of nutritional support does not appear to be a significant factor in mortality.

Flow Cytometric Analysis of Early Bone Marrow Progenitors CD34+/CD117+ Cells

Dual-color flow cytometric analysis of bone marrow cells labeled with anti-CD34 and anti-CD117 was used to assess the number of early progenitor cells within the bone marrow following sham, burn and burn sepsis treatments. The results are displayed in Figure 1 with panels representing one of the 3 injury treatment groups with either intact or depleted peripheral norepinephrine. High florescent intensity events representing cells bearing both CD117 and CD34 stem cell markers found in the upper right quadrant represent very early progenitor cells.

The percentage of the total cell population in norepinephrine intact animals appearing in the upper right quadrant increases from sham (3.5 ± 0.7%), to burn (5.7 ± 1.0%) with the highest levels resulting from burn sepsis (9.8±3.1%, 2.8 fold increase above sham conditions). Animals depleted of norepinephrine prior to the injury treatment protocol show similar expansion of the dual staining compartment increasing from sham (3.6 ± 0.5%) to burn (4.6 ± 0.2%) to an even greater level in burn sepsis (7.6 ± 1.3%, 2.1-fold increase above sham conditions). The percentage of cells in the lower left quadrant also appears to shift following injury treatment (group data not shown) but neither these changes nor those in the upper right quadrant were found to be different using the Analysis of Variance test statistic. These results led us to conduct more detailed analysis by examining the potential of these cells to proliferate and differentiate under optimal in vitro conditions through assessment of their clonogenic potential. Since previous work suggested injury-induced expansion of ER-MP12+ bone marrow cells,20 we also examined the clonogenic potential of ER-MP12+ cells under conditions of intact and depleted tissue norepinephrine.

Expansion of CD117+ and ER-MP12+ Compartments in Response to Injury: Comparisons of Clonogenic Potential

CD117+ or ER-MP12+ cells enriched from bone marrow were cultured in semisolid agar with appropriate growth factors for 7 days and proliferation was assessed by counting the number of colonies of 50 or more cells that developed during that time. Figure 2 displays the results of these experiments for CD117+cells, with panel A displaying results from animals with intact norepinephrine. In comparison to the sham treatment group, the burn and burn sepsis treatment resulted in increasing number of M- and GM-CSF responsive colonies (P < 0.05 in all cases) reflecting compartment expansion with injury. Panel B displays results of the same paradigm as in panel A but where animals were subjected to depletion of norepinephrine prior to the injury protocol. In panel B there are significant increases in M- and GM-CSF responsive colonies formed following burn sepsis compared with sham (P < 0.05). The most striking contrast however, is the overall reduction in the magnitude of colonies formed in all groups in panel B compared with panel A. Thus, with markedly reduced levels of bone marrow norepinephrine prior to injury, the clonogenic potential of CD117+ cells is reduced under all conditions.

Results of clonogenic assessment of ER-MP12+ cells subjected to the same experimental conditions as for CD117+ are presented in Figure 3. Figure 3A is based on findings from animals with intact norepinephrine whereas Figure 3B displays results based on findings from animals with depleted norepinephrine. In panel A following injury treatment there was a significant increase in the number of M- and GM-CSF responsive colonies formed in response to optimal growth factors with burn treatment (P < 0.05 vs. sham) and an even greater clonogenic response following burn sepsis treatment (P < 0.05 vs. sham and burn). In panel B ER-MP12+ cells taken from animals with depleted norepinephrine levels displayed a significant clonogenic response to injury but had markedly reduced colony growth in all treatment groups compared with cells from norepinephrine intact animals as seen in Figure 3A.

LPS-Evoked Cytokine Responses of CD117+ and ER-MP12+ Progenitor-Derived Macrophage Cells

Figure 4A contains results of IL-6 production in cells from animals subjected to sham, burn, and burn sepsis contrasting responses from CD117+ and ER-MP12+ progenitor-derived macrophages. The overall pattern of IL-6 production is quite constant between different injury treatments for the CD117+ progenitor-derived macrophages although the burn sepsis group is significantly less that either burn or sham (P < 0.05). The LPS-evoked IL-6 response of ER-MP12+ progenitor-derived macrophages is markedly elevated after the burn sepsis treatment (P < 0.05 vs. both burn and sham).

In Figure 4B, results of CD117+ progenitor-derived macrophage responses to LPS show comparable levels of TNF-α production after sham and burn sepsis (P > 0.05 sham vs. burn sepsis) but much lower levels after burn treatment (P < 0.05 burn vs. both sham and burn sepsis). ER-MP12+ progenitor-derived macrophages produced low levels of TNF-α in response to LPS in both sham and burn groups but a 7-fold increase above these levels after burn sepsis (P < 0.05 burn sepsis versus both sham and burn).

The Influence of Norepinephrine on LPS-Evoked Cytokine Responses of CD117+ and ER-MP12+ Progenitor-Derived Macrophages

Figure 5 displays the results of IL-6 and TNF-α measurements in supernatants from CD117+ progenitor-derived macrophages stimulated with endotoxin. IL-6 responses (Fig. 5A) in cells taken from mice with intact norepinephrine are approximately 4-fold higher than those taken from mice with depleted norepinephrine in sham, burn and burn sepsis treatment groups (P < 0.05 for all comparisons). Figure 5B indicates that depletion of norepinephrine markedly reduced TNF-α production in each treatment group (P < 0.05 for each treatment group). There was an approximate 50% reduction in both sham and burn treatment groups while there was a 70% reduction in TNF-α production in the burn sepsis group when norepinephrine was depleted.

Figure 6 displays results from ER-MP12+ progenitor-derived macrophage. In Figure 6A, IL-6 production in macrophage from norepinephrine intact animals was greater than that from norepinephrine depleted animals in each treatment group (P < 0.05 for all treatments) but the differences were most striking in the burn sepsis group.

In Figure 6B, ER-MP12+ progenitor-derived macrophage production of TNF-α was markedly lower in sham and burn groups with intact compared with those with depleted norepinephrine (P < 0.05 for each group). However, these high levels of TNF-α production in the norepinephrine depleted and low levels of TNF-α production in the norepinephrine intact groups are reversed in burn sepsis. Burn sepsis treatment in norepinephrine-depleted animals resulted in a 4-fold lower macrophage TNF-α response compared with macrophage response from norepinephrine intact animals (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Both our FACS data and our clonogenic potential data indicate that following injury there is an expansion of M-CSF and GM-CSF responsive cells in both the early progenitor (CD117) and myeloid committed progenitor (ER-MP12) enriched compartments. Furthermore, treatment with pharmacologic agents that deplete sympathetic neurotransmitter prior to injury negates the magnitude of the overall expansion while maintaining the injury-induced effect in both populations. These results are strikingly similar to our previous report involving clonogenic potential of total bone marrow cells and suggest a level of bone marrow norepinephrine depletion similar to our previously documented level.6 The present findings suggest that sympathetic stimulation enhances both early and late bone marrow progenitor-expansion into the monocytic lineage and extends our previous finding that norepinephrine profoundly enhances myelopoiesis in response to burn sepsis.6 While the clonogenic response of both CD117 and ER-MP12 progenitors to GM-CSF and M-CSF appear to be similar, LPS-stimulated cytokine responses are heterogeneous and appear to depend on the stage of the developmental program from which each progenitor population is isolated, the type of injury condition and the degree of sympathetic innervation.

Injury-induced alterations in macrophage cytokine responses to LPS suggest that bone marrow progenitors acquire the ability to respond to injury conditions between the CD117 progenitor stage and the bi-potential ER-MP12 progenitor stage. This is supported by the findings (Fig. 4) that injury increases the LPS-provoked IL-6 responses in ER-MP12 progenitor derived macrophages whereas the same experimental paradigm of responses in CD117 derived cells is not influenced by injury pretreatment. Similarly, TNF-α responses are injury dependent in ER-MP12 derived cells but in cells derived from CD 117 progenitors macrophage TNF-α responses were the same following both burn sepsis and sham protocols.

The influences of norepinephrine on LPS-stimulated cytokine responses appear to be present very early in the development of bone marrow progenitors as suggested by results displayed in Figures 5 and 6. In macrophages derived from both CD117 and ER-MP12 progenitors, all treatment protocols resulted in reduced IL-6 responses to LPS when progenitor cells were taken from norepinephrine depleted animals compared with those with intact norepinephrine stores (Figs. 5A and 6A). This same pattern in all treatment groups was also observed for TNF-α in CD117 derived macrophages (Fig. 5B) but TNF-α responses in ER-MP12 progenitor derived macrophages were increased in sham and burn groups but decreased in burn sepsis (Fig. 6B). Results in this later group are not easily explained but could possibly involve inadequate norepinephrine depletion or errors in the test system. However, it is important to point out that all results in Figures 5 and 6 involving IL-6 and TNF-α were based on the same experimental samples from the same experimental animals. Beyond the influence of norepinephrine on cytokine responses in sham and burn groups, the most pronounced effects of norepinephrine appear to be on macrophage development following burn sepsis. In every experimental burn sepsis group (Figs. 5A, 5B, 6A and 6B) LPS-stimulated IL-6 and TNF-α are always markedly reduced in cells derived from progenitors taken from mice with depleted compared with intact norepinephrine. The importance of this reduction in cytokine response can be related to findings in patients where high levels of IL-6 and TNF-α were found in nonsurvivors with documented shock.21–23 Furthermore, results of the identical experimental injury protocol with the same strain of mice demonstrated that depletion of norepinephrine prior to thermal injury with sepsis was found to have a marked survival benefit.6 These findings suggest that attenuated IL-6 and TNF-α responses to LPS in mature macrophages are related to reduced stores of norepinephrine and may be protective in the sequela of events following thermal injury with sepsis. Alternatively, depletion of norepinephrine in the clinical setting could possibly compromise postinjury metabolic responses as well as vascular regulatory mechanisms and many questions regarding the role of norepinephrine in thermal injury and sepsis remain unanswered.

The action of norepinephrine to increase macrophage cytokine production can involve direct cellular effects.11,12 However, in the present study the influence of catecholamines are confined to the 72 hours injury period prior to isolation of bone marrow progenitors. During the 7 days of culture the progenitor-derived macrophages are only exposed to the constituents of the defined catecholamine free-media and the macrophage responses to LPS over the final 18 hours therefore could be influenced by the bone marrow milieu only in the whole animal during the injury state. Furthermore, during the injury state endotoxin is not likely to be of major direct influence on the progenitor cells since these progenitor cells do not respond to LPS stimulation and only the progenitor-derived mature macrophage respond to LPS by producing cytokines (unpublished observations).

The concept that monocytes and macrophages express a functional heterogeneity has been previously proposed in peripheral blood monocytes. Miller-Granziano et al,24 and Schinkel et al25 have described subsets of human macrophage in trauma and sepsis through Fc receptor linked activation. Although until now similar demonstration of functionally different subsets have not been previously reported within the hematopoietic paradigm, Ogle et al26 had demonstrated that total bone marrow cells harvested from thermally injured rats produced enhanced amounts of TNF-α, IL-1, and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) when stimulated with LPS compared with sham-injured animals. However, the origin of such responses and whether they involved heterogeneous macrophage phenotypes was never addressed. Our results provide evidence that monocytes that develop within the bone marrow under injury conditions may exhibit a diverse functional phenotype and such expression may form a template for further changes in the periphery dictated by their local microenvironment.

We have previously demonstrated that burn sepsis stimulates sympathetic norepinephrine release within the bone marrow compartment6 and this increased neurotransmitter may alter the phenotypic development of bone marrow monocyte progenitors through paracrine signaling. Paracrine signaling may also involve changes in inflammatory mediators including cytokines and prostanoids within bone marrow after thermal injury and sepsis. For example, prostaglandin PGE2 increases in response to inflammation and recent studies have demonstrated PGE2 -mediated regulation of bone marrow mast cells in terms of IL-6, GM-CSF, and endoperoxide synthase-2 production.27–29 Our previous studies have demonstrated a clear advantage to both survival and bone marrow myelopoiesis when either PGE2 production is abrogated or when PGE2's actions are inhibited with a specific PGE2 receptor antagonist.20,30

Radioligand binding studies and pharmacologic studies in whole animals suggest the presence of functional adrenergic receptors within the bone marrow compartment and in dendritic cells.31–33 Complementary to the actions of catecholamines on cytokine release, recent reports suggest that cytokines may modulate adrenergic receptors. Heijnen et al34 examined the effect of proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 on the mRNA levels of α1-adrenergic receptor subtypes in THP-1-cultured monocytes. THP-1 cells cultured with IL-1β or TNF-α induced α1a adrenergic receptor mRNA whereas exposure to IL-1β or TNF-α did not cause any changes for α1b but reduced the expression of α1d receptor mRNA. In addition, Wahle et al35 report that IL-2 mediates an up-regulation of β2 adrenergic receptors on human CD8+ but not CD4+ lymphocytes in vitro. This interaction of catecholamines and cytokines lends further credence to our observation that norepinephrine is a potent modulator of monocyte progenitor development into monocytes/macrophages and their subsequent function.

From the clinical perspective it would be useful to understand the degree to which patient responses and recovery are altered by the specific degree of injury. However, in the present study little can be gleaned in regard to the degree of injury since only one level of thermal injury and infectious challenge was used. However, the addition of thermal injury with infectious challenge did result in a graded clonogenic response (Fig. 2A and 3A) as well as a heightened cytokine response to LPS challenge in ER-MP12 derived macrophages (Fig. 4A and 4B). This suggests that the development of subsets of mature macrophage some of which have heightened LPS-stimulated cytokine responses may be dependent on the severity of injury. Patient variations in cytokine levels, hyper- in contrast to hypo-inflammatory status and the time course of these changes5 could be influenced by the onset of different subsets of macrophages during the development of sepsis. Our present understanding of external factors controlling macrophage subset development is limited and further work to identify and characterize subsets of macrophage that may occur during the development of sepsis is critical to attain a more complete understanding of the pathophysiology of sepsis.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grants RO1 GM61746 (S.B.J.), RO1 GM56424 (R.S.), and RO1 GM42577 (R.L.G.).

Reprints: Stephen B. Jones, PhD, Room 4219; Bldg 110, Loyola University Medical Center, 2160 South First Avenue, Maywood, IL. E-mail: sjones@lumc.edu.

Current Address of M. J. Cohen: Department of Surgery, Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke's Medical Center, 1650 West Harrison St., Chicago, IL 60612.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sands KE, Bates DW, Lanken PN, et al. Epidemiology of sepsis syndrome in 8 academic medical centers. Academic Medical Center Consortium Sepsis Project Working Group. JAMA. 1997;278:234–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meakins JL, Pietsch JB, Bubenick O, et al. Delayed hypersensitivity: indicator of acquired failure of host defenses in sepsis and trauma. Ann Surg. 1977;186:241–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lederer JA, Rodrick ML, Mannick JA. The effects of injury on the adaptive immune response. Shock. 1999;11:153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oberholzer A, Oberholzer C, Moldawer LL. Sepsis syndromes: understanding the role of innate and acquired immunity. Shock. 2001;16:83–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE. The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:138–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang Y, Shankar R, Gamboa M, et al. Norepinephrine modulates myelopoiesis after experimental thermal injury with sepsis. Ann Surg. 2001;233:266–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang Y, Shankar R, Gamelli R, et al. Dynamic norepinephrine alterations in bone marrow: evidence of functional innervation. J Neuroimmunol. 1999;96:182–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bone RC. Toward a theory regarding the pathogenesis of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome: what we do and do not know about cytokine regulation. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:163–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faist E. The mechanisms of host defense dysfunction following shock and trauma. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;216:259–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergmann MaS, T. Immunomodulatory effects of vasoactive catecholamines. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2002;114:752–761. [PubMed]

- 11.Spengler RN, Chensue SW, Giacherio DA, et al. Endogenous norepinephrine regulates tumor necrosis factor-alpha production from macrophages in vitro. J Immunol. 1994;152:3024–3031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou M, Yang S, Koo DJ, et al. The role of Kupffer cell alpha(2)-adrenoceptors in norepinephrine-induced TNF-alpha production. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1537:49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zsebo KM, Williams DA, Geissler EN, et al. Stem cell factor is encoded at the Sl locus of the mouse and is the ligand for the c-kit tyrosine kinase receptor. Cell. 1990;63:213–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Bruijn MF, Slieker WA, van der Loo JC, et al. Distinct mouse bone marrow macrophage precursors identified by differential expression of ER-MP12 and ER-MP20 antigens. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:2279–2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walker HL, Mason AD Jr. A standard animal burn. J Trauma. 1968;8:1049–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gamelli RL, He LK, Liu H. Macrophage suppression of granulocyte and macrophage growth following burn wound infection. J Trauma. 1994;37:888–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ichikawa Y, Pluznik DH, Sachs L. In vitro control of the development of macrophage and granulocyte colonies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1966;56:488–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bradley TR, Metcalf D. The growth of mouse bone marrow cells in vitro. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci. 1966;44:287–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shoup M, Weisenberger JM, Wang JL, et al. Mechanisms of neutropenia involving myeloid maturation arrest in burn sepsis. Ann Surg. 1998;228:112–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santangelo S, Gamelli RL, Shankar R. Myeloid commitment shifts toward monocytopoiesis after thermal injury and sepsis. Ann Surg. 2001;233:97–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calandra T, Baumgartner JD, Grau GE, et al. Prognostic values of tumor necrosis factor/cachectin, interleukin-1, interferon-alpha, and interferon-gamma in the serum of patients with septic shock. Swiss-Dutch J5 Immunoglobulin Study Group. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:982–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calandra T, Gerain J, Heumann D, et al. High circulating levels of interleukin-6 in patients with septic shock: evolution during sepsis, prognostic value, and interplay with other cytokines. The Swiss-Dutch J5 Immunoglobulin Study Group. Am J Med. 1991;91:23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeh FL, Lin WL, Shen HD, et al. Changes in serum tumour necrosis factor-alpha in burned patients. Burns. 1997;23:6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller-Graziano CL, Szabo G, Kodys K, et al. Aberrations in post-trauma monocyte (MO) subpopulation: role in septic shock syndrome. J Trauma. 1990;30(12 Suppl):S86–S96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schinkel C, Sendtner R, Zimmer S, et al. Functional analysis of monocyte subsets in surgical sepsis. J Trauma 1998;44(5):743–748; discussion 748–749. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Ogle CK, Valente JF, Guo X, et al. Thermal injury induces the development of inflammatory macrophages from nonadherent bone marrow cells. Inflammation. 1997;21:569–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen M, Solle M, Audoly LP, et al. Receptors and signaling mechanisms required for prostaglandin E2-mediated regulation of mast cell degranulation and IL-6 production. J Immunol. 2002;169:4586–4593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diaz BL, Fujishima H, Kanaoka Y, et al. Regulation of prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase-2 and IL-6 expression in mouse bone marrow-derived mast cells by exogenous but not endogenous prostanoids. J Immunol. 2002;168:1397–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gomi K, Zhu FG, Marshall JS. Prostaglandin E2 selectively enhances the IgE-mediated production of IL-6 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor by mast cells through an EP1/EP3-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2000;165:6545–6552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shoup M, He LK, Liu H, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor NS-398 improves survival and restores leukocyte counts in burn infection. J Trauma 1998;45:215–20; discussion 220–1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Muthu K, Deng J, Gamellil R, et al. Beta adrenergic receptor expression in bone marrow cells following thermal injury with sepsis (Abstract). Shock 2003;19:64. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maestroni GJ, Conti A. Modulation of hematopoiesis via alpha 1-adrenergic receptors on bone marrow cells. Exp Hematol. 1994;22:313–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maestroni GJ, Conti A. Noradrenergic modulation of lymphohematopoiesis. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1994;16:117–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heijnen CJ, Rouppe van der Voort C, van de Pol M, et al. Cytokines regulate alpha(1)-adrenergic receptor mRNA expression in human monocytic cells and endothelial cells. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;125:66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wahle M, Stachetzki U, Krause A, et al. Regulation of beta2-adrenergic receptors on CD4 and CD8 positive lymphocytes by cytokines in vitro. Cytokine. 2001;16:205–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]