Abstract

NF-κB induces the expression of genes involved in immune response, apoptosis, inflammation, and the cell cycle. Certain NF-κB-responsive genes are activated rapidly after the cell is stimulated by cytokines and other extracellular signals. However, the mechanism by which these genes are activated is not entirely understood. Here we report that even though NF-κB interacts directly with TAFIIs, induction of NF-κB by tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) does not enhance TFIID recruitment and preinitiation complex formation on some NF-κB-responsive promoters. These promoters are bound by the transcription apparatus prior to TNF-α stimulus. Using the immediate-early TNF-α-responsive gene A20 as a prototype promoter, we found that the constitutive association of the general transcription apparatus is mediated by Sp1 and that this is crucial for rapid transcriptional induction by NF-κB. In vitro transcription assays confirmed that NF-κB plays a postinitiation role since it enhances the transcription reinitiation rate whereas Sp1 is required for the initiation step. Thus, the consecutive effects of Sp1 and NF-κB on the transcription process underlie the mechanism of their synergy and allow rapid transcriptional induction in response to cytokines.

The family of NF-κB transcription factors is a central component of the cellular response to a broad range of extracellular signals, many of them are related to immunological functions and stress. NF-κB controls the expression of a large number of genes including inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, immunological factors, adhesion molecules, cell cycle regulators, and pro- and antiapoptotic factors (24). A major pathway regulating NF-κB activity involves its nuclear transport. In unstimulated cells, NF-κB is retained in the cytoplasm in an inactive form by IκB proteins. Signals that activate NF-κB trigger ubiquitination and degradation of IκB by the proteosome, resulting in transport of NF-κB into the nucleus and transcriptional activation of responsive genes. Since IκBα is one of the NF-κB target genes, the newly synthesized IκBα negatively regulates NF-κB, thus forming an autoregulatory loop.

In the nucleus, transcriptional activation by NF-κB involves its association with multiple coactivators. We reported previously that the substoichiometric TFIID subunit, TAFII105, which is enriched in B cells, interacts directly with p65/Re1A, a member of the NF-κB family, and is important for activation of a subset of NF-κB-dependent antiapoptotic genes in vivo (30, 36, 37). Likewise, other TFIID subunits such as hTAFII250, hTAFII80, and hTAFII28 were reported to bind to p65/Re1A (8), although the physiological importance of these interactions was not investigated. In addition to TFIID, the coactivator protein CREB-binding protein CBP and its homolog p300 were reported to be involved in transcription activation by the p65/Re1A subunit of NF-κB (6, 25). p65 was also found to interact specifically with the composite coactivator ARC/DRIP, and this complex supports NF-κB-dependent transcriptional activation in vitro (20). Despite of all these findings, the exact mechanism by which NF-κB stimulates the transcription of its responsive genes remains largely unknown.

Transcription of mRNA-encoding genes is a multistep process roughly divided into initiation, elongation, and termination, with initiation being a major regulatory target. Initiation by RNA polymerase II (Pol II) is a highly complex step and involves the activities of a large number of proteins. General transcription factors and Pol II are assembled around the transcription start site, and gene-specific transcription factors (activators or repressors) bind to enhancer elements and communicate with the general transcription machinery through coactivators (3, 22). Among the general transcription factors, TFIID is responsible for recognition and binding of the core promoter elements. TFIID-promoter interaction promotes the assembly of the other general transcription factors and Pol II either in an orderly manner or as a Pol II holoenzyme which is already associated with a subset of general transcription factors and other factors. TFIID is a multisubunit complex composed of the TATA-binding protein (TBP) and 12 to 14 TBP-associated factors (TAFIIs). TAFIIs interact with core promoter elements and are required for core promoter recognition. In addition, TAFIIs act as molecular bridges between activators and the basal transcription machinery, through their direct interaction with activation domains of the activators (reviewed in references 2 and 10). Activator-TAFII interaction has been suggested to enhance the recruitment of TFIID to the core promoter. Furthermore, experiments using partially reconstituted TFIID complexes indicated that synergism between multiply bound activators is achieved by TFIID recruitment through multiple activator-TAFII interactions (28). These findings are consistent with earlier studies suggesting that synergistic transcriptional activation by multiply bound activators involves the simultaneous association of these activators with components of the general transcription machinery (4, 18).

Here, we have investigated the mechanism of transcriptional activation of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)-responsive genes by NF-κB in vivo and in vitro. The results indicate that the promoters of a subset of NF-κB-regulated genes are constitutively bound by the general transcription machinery. Using the TNF-α-responsive A20 promoter as a model, we found that constitutive association of the general transcription apparatus with the A20 promoter is mediated by the transcription factor Sp1 and that this is important for the immediate induction by NF-κB following TNF-α stimulation. Consistent with this, we found that NF-κB activity is directed to a post-preinitiation complex formation step, the enhancement of the transcription cycle rate, whereas Sp1 is essential for the initiation step. These results provide the mechanistic basis for rapid induction of TNF-α-induced genes and reveal a novel mode of synergism between Sp1 and NF-κB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

The A20 promoter used for the in vitro binding and in vitro transcription assays was generated by inserting a HindIII-BamHI fragment containing the A20 promoter from the A20-Luc reporter plasmid into pBC-SK− digested with HindIII and BamHI. To construct the Sp1-sites-deleted A20 promoter, a BsaAI-BamHI fragment containing the region from −74 to+12 of the A20 promoter was inserted into EcoRV-BamHI of the pBC-SK− vector. To construct the NF-κB-mutated A20 promoter, a triple ligation reaction was performed that contained a BsaAI-HindIII fragment spanning positions −229 to −74 of the A20 promoter and a PCR fragment containing −56 to +12 of the A20 promoter digested withBamHI. The PCR fragment contained the 3′ NF-κB site, which was mutated. The primers used to generate this fragment are 5′-GTGGAAATCGATGGGCCTACAACCCGCATACA-3′ and the T3 primer (see below). A20-Luc and A20Δ NF-κB-Luc were described previously (35). A20-ΔSp1-Luc was constructed by inserting a BsaAI-PstI fragment containing −74 to +12 of the A20 promoter into HindIII (filled in)-PstI sites of the promoterless reporter vector pLuc.

Immobilized template-binding assay.

The A20 promoter fragment and its derivatives were ligated to a double-stranded biotinylated oligonucleotide. The biotinylated promoter fragments were bound to streptavidin-conjugated magnetic beads (Dynabeads). For in vitro binding reactions, 5 μl of bead suspension containing 200 ng of DNA was incubated with 25 to 100 μg of Jurkat cell nuclear extract in binding buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 20% glycerol, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.01% NP-40, 10 μM ZnSO4) for 30 min at room temperature. The beads were then washed three times with binding buffer, eluted with protein-loading buffer, and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblot analysis.

Antibodies.

Anti-TAFII105 antibodies were described previously (5). Anti-TFIIB was a gift from Yosef Shaul. Anti-Pol II is the SWGI6 monoclonal antibody (Babco). Anti-p65, anti-Sp1, anti-CBP, and anti-p300 and anti-TAFII250 were obtained from Santa-Cruz Biotechnology Inc.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation.

The chromatin immunoprecipitation assay was performed on the basis of previously published methods but with some modifications (23). Jurkat T cells (108) were either untreated or treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 1 h and then cross-linked in vivo with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. The cells were washed once with cold phosphate-buffered saline, once with 2.5 ml of buffer I (10 mM HEPES [pH 6.5], 10 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 0.25% Triton X-100), and once with buffer II (10 mM HEPES [pH 6.5], 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 200 mM NaCl). They were resuspended in 1 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 8.1], 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, 0.8μg of pepstatin A per ml, 0.6 μg of leupeptin per ml, 1 mM phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride) and sonicated 10 times for 10 s each time. The extract was then clarified by centrifugation for 15 min in a microcentrifuge at 4°C and diluted 10-fold with dilution buffer solution (20 mM Tris [pH 8.1], 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100) to yield the solubilized chromatin. Next, salmon sperm DNA (50 μg/ml), tRNA1 (100 μg/ml), and bovine serum albumin (1 mg/ml) were added, and the extract was precleared by addition of 50 μl of 50% protein A-Sepharose suspension beads per ml and incubation for 30 min on a rotator wheel. After a 15-min centrifugation at 4°C, the extract was transferred to a new tube. A 5-μl sample of the soluble extract was analyzed on a 1% agarose gel to confirm an average size of 1 kb for the DNA and the relative amount of the input material for each sample. For immunoprecipitation, 1 μl of anti-TBP, anti-TAFII105, anti-TFIIB, anti-Pol II, or control serum was added to 0.5 ml of the soluble chromatin (corresponding to 5 × 106 to 10 × 106 cells) and the mixture was incubated from 4 h to overnight at 4°C. After centrifugation, the extracts were transferred to a new tube containing 25 to 30 μl of 50% protein A-Sepharose suspension and incubated at 4°C for 1 to 2 h in rotating wheel. The beads were then washed sequentially with TSE-150mM NaCl (TSE is 20 mM Tris [pH 8.1], 2 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, and 150 or 500 mM NaCl), TSE-500 mM NaCl, buffer III (10 mM Tris [pH 8.1], 0.25 M LiCl, 1% NP-40, 1% deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA), and three times with TE (10 mM Tris 8, 1 mM EDTA). The immune complexes were then eluted off the Sepharose beads by incubating the beads three times with 100 μl of elution buffer (1% SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO3, 20 μg of glycogen per ml) for 10 min each. The combined eluates were heated at 65°C for 4 h to reverse the formaldehyde cross-links. The eluates were extracted once with phenol-chloroform and once with chloroform, precipitated with ethanol, and resuspended in 20 μl of TE. A 2-μl sample was used for PCR.

The primers used for the A20 promoter were 5′-CAGCCCGACCCAGAGAGTCAC-3′ and 5′-CGGGCTCCAAGCTCGCTT-3′. As in some experiments with the A20 promoter, the PCR product was undetectable by ethidium bromide staining and so it was detected by Southern blot hybridization using an internal oligonucleotide as a probe: 5′-CCTACAACCCGCATACAACTG-3′. The IκB promoter pair was 5′-AAGGCTCACTTGCAGAGG-3′ and 5′-GGACTGCTGTGGGCTCTG-3′; the FasL promoter pair was 5′-TAGCCCCACTGACCATTCTC-3′ and 5′-GAGGAGGCAAGCTGGATCTC-3′; and the IEX-1 promoter pair was 5′-GTCTCCACCCACTCCCTTTG-3′ and 5′-GTGTAAGGCCAAGTGAGGGTC-3′.

In vitro transcription assays and purification of transcription factors.

The in vitro transcription was carried out by incubating 18 μl of nuclear extract at 30°C for 30 min in transcription buffer (100 mM KCl, 25 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 12.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, and 1 mM dithiothreitol) with 200 ng of plasmid DNA template in a 36-μl reaction mixture also containing 10 μM ZnSO4. Transcription was initiated by addition of 4 μl of 5 mM nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs) mixture. The reaction was terminated after 10 min by the addition of 100 μl of stop solution (0.2 M NaCl, 20 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, 0.25 mg of yeast tRNA per ml, 50 μg of proteinase K per ml) and incubation at room temperature for 2 min. In single-round transcription assays, 0.2% Sarkosyl was added to the reaction mixture 1.5 min after the initiation of transcription by NTPs and incubation was continued for additional 8.5 min. The RNA was isolated by phenol-chloroform (1:1) and subsequent chloroform extraction followed by ethanol precipitation. The RNA products were detected by extension of end-labeled primer (T3 for the A20 promoter [5′-AATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGG-3′] and Luc for the cyclin A promoter [5′-CTTTATGTTTTTGGCGTCTTCC-3′]). The RNA samples were resuspended in 10 μl of reaction mixture containing 25 fmol of labeled primer (an excess over the RNA template), 2 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.8), 0.2 mM EDTA and 0.25 M KCl, and then denatured at 85°C for 5 min and annealed at 50°C for 45 to 60 min. A 25-μl volume of extension mixture composed of 2.5 U of avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (Promega), 20 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.7), 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.33 mM dNTPs was added to the annealed primer-RNA duplexes, and an extension reaction was performed at 37°C for 15 min. The cDNA products were ethanol precipitated, separated on an 8% urea-polyacrylamide gel, and visualized with a Phosphoimager (Fuji, BAS 2500).

Sp1 was purified from HeLa cells infected with vaccinia virus, which directs the expression of Sp1. Sp1 was purified as previously described (9). p65 homodimer was purified as a six-histidine tag fusion protein from Escherichia coli strain BL-21 DE3 as described previously (32).

RESULTS

TAFII105-TFIID is not recruited to the A20 promoter by NF-κB in vivo,

We have previously found that interaction of p65/Re1A with TAFII105 is important for activation of a subset of NF-κB target genes, and we identified the TNF-α/NF-κB-induced A20 gene as a target for the substoichiometric TAFII105-TFIID complex (30, 37). The A20 gene encodes a cytoplasmic zinc finger protein important for inhibition of TNF-α-mediated programmed cell death and inflammation (17). Since earlier in vitro transcription studies indicated that TAF-activator interactions serve to enhance the recruitment of TFIID to the core promoter (28), we examined whether NF-κB recruits TAFII105-TFIID complex to the A20 promoter. For this purpose, we analyzed the effect of NF-κB induction on core promoter occupancy by TFIID in living cells by employing an in vivo formaldehyde cross-linking technique followed by immunoaffinity purification of DNA-protein complexes (CHIP assay). We used the T-cell line Jurkat, in which NF-κB proteins are excluded from the nucleus but can be induced to enter the nucleus by TNF-α (Fig. 1A). Soluble in vivo cross-linked chromatin extracts were prepared from cells that were either untreated or treated with TNF-α, which rapidly induces A20 gene transcription (reference 21 and data not shown). These extracts were used for immunoprecipitation with TAFII105, TBP, or control antibodies, and the immunopurified DNA was analyzed by PCR for the presence of A20 promoter. Interestingly, both TBP and TAFII105 bound the A20 promoter in the absence of NF-κB-activating signal, and their levels were not significantly changed upon TNF-α treatment (Fig. 1B). Association of p65/Re1A with the A20 promoter in vivo was observed following TNF-α treatment (Fig. 2A, compare lanes 5 and 11). To ensure that equivalent amounts of extracts were used for immunoprecipitations, the input of each extract was examined by increasing the number of PCR cycles (Fig. 1B, middle panel). The enrichment of the A20 promoter by TBP and TAFII105 antibodies is specific, since a downstream sequence of the A20 gene (nucleotides 2394 to 2693 of the cDNA, encoded by the same exon) was not enriched by these antibodies (Fig. 1B, lower panel).

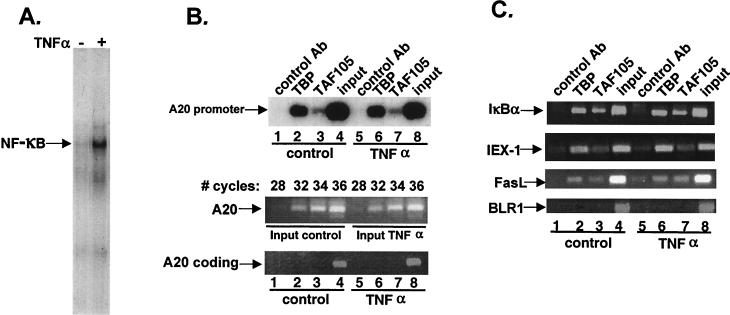

FIG. 1.

Induction of the NF-κB-A20 promoter interaction does not enhance TFIID binding. (A) TNF-α induces transport of NF-κB into the nucleus. Jurkat cells were stimulated for 1 h with TNF-α (10 ng/ml), and nuclear extracts from untreated or treated cells were used in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay with a labeled NF-κB-binding site. The arrow indicates the NF-κB complex. (B) The promoter of the A20 gene is preoccupied by TFIID in vivo. Jurkat cells were stimulated for 1 h with TNF-α or not stimulated and cross-linked in vivo with 1% formaldehyde. Soluble chromatin was prepared from these cells and used for immunoprecipitation with the indicated antibodies (CHIP assay). The immunoprecipitated DNAs were analyzed for the enrichment of the A20 of the promoter by PCR. In the middle panel, the input extract (0.1%) was subjected to increasing numbers of PCR cycles with the same primer set to check for the relative amount of the control or TNF-α-induced extracts used for immunoprecipitations. In the lower panel, samples from the same immunoprecipitated DNAs were subjected to PCR analysis using primers corresponding to the coding region of the A20 gene. (C) Analysis of a subset of NF-κB-responsive promoters by the CHIP assay as in panel B. The BLR1 gene is an NF-κB regulated gene that is specifically expressed in B cells and is used as a control for specificity.

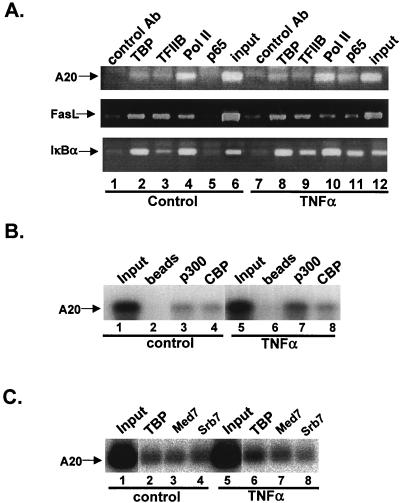

FIG. 2.

Effect of NF-κB induction on promoter occupancy by the transcription apparatus. (A) CHIP assay using soluble chromatin extract from control or TNF-α-treated Jurkat cells and antibodies directed against TBP, TFIIB, Pol II, and the p65 component of NF-κB. The precipitated DNAs were used for PCR amplifications with primers spanning the core promoters of the indicated NF-κB target genes. (B) CHIP assays with antibodies directed against the coactivators CBP and p300 and analysis of A20 promoter by PCR. (C) CHIP assay with antibodies against the Mediator components Med7, Srb7, and TBP, which serve as a control. To confirm the amplification of the A20 promoter, the PCR products were analyzed by Southern blotting.

Next we asked whether preoccupation of core promoter by TFIID is restricted to the A20 gene or is common to other NF-κB-TAFII105-regulated genes. Therefore we examined the interaction of TBP and TAFII105 with the core promoter of three additional genes previously reported to be regulated by NF-κB in Jurkat cells: IκBα (12, 16), FasL (11, 13), and IEX-1 (35). The results indicate that all these promoters are bound by TBP and TAFII105 prior to the TNF-α stimulus (Fig. 1C). To confirm the specificity of TFIID interaction with these promoters, a similar analysis was performed with the promoter of BLR1, a B-cell-specific NF-κB target gene (24) that is not expressed in Jurkat cells. This promoter was not specifically immunoprecipitated by the antibodies (Fig. 1C).

The promoters of NF-κB target genes are bound by TFIIB, Pol II, and the coactivators CBP and p300 in the absence of NF-κB in vivo.

Since the activation function of NF-κB is not directed to TFIID recruitment, we examined whether it promotes the recruitment of other components of the basal transcription machinery. A similar CHIP assay was performed using antibodies against TFIIB and the large subunit of Pol II (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, like TBP (Fig. 2A, lanes 2 and 8), TFIIB and Pol II bound all these promoters in the presence (lanes 9 and 10) and absence (lanes 3 and 4) of NF-κB binding. Taken together, these findings provide evidence that the promoters of at least some NF-κB-inducible genes are accessible to the preinitiation complex even before the binding of their major regulatory factor, NF-κB.

Next we examined the effect of NF-κB induction on promoter occupancy by the coactivators CBP and p300, previously shown to be important for its transcriptional activity (6, 25). A CHIP assay was performed with chromatin extracts of control and stimulated Jurkat cells and antibodies directed against either CBP or p300. As with the general transcription machinery, NF-κB did not recruit CBP and the binding of p300 was slightly enhanced (Fig. 2B). Similarly, the Srb7 and Med7 subunits of the Mediator complex involved in NF-κB-induced transcription (20) were found associated with the A20 promoter prior to NF-κB induction (Fig. 2C).

Recruitment of the general transcription machinery is mediated by the constitutive transcription activator Sp1.

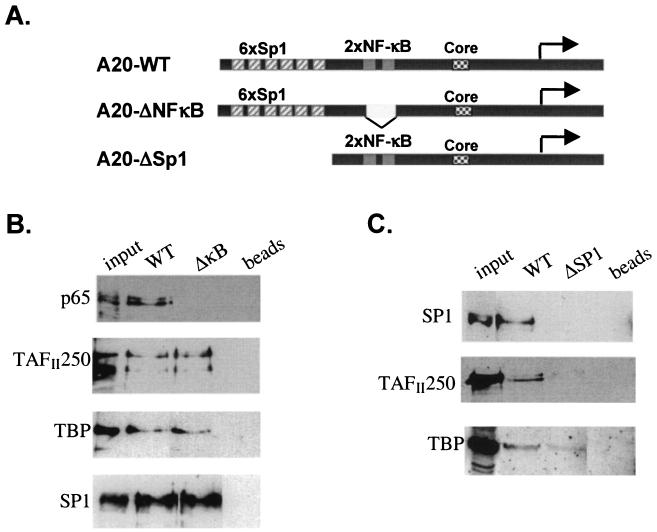

To examine further the effect of NF-κB on core promoter occupancy by TFIID, we used the A20 promoter as a model since its organization is relatively simple (15). It contains six Sp1- and two NF-κB-binding sites in front of a core promoter lacking a TATA element (Fig. 3A). We used nuclear extracts derived from nonstimulated cells supplemented with purified recombinant p65/Re1A, which is active in transcription (see Fig. 5D), in binding reactions with either the wild-type or NF-κB-mutated A20 promoter DNA that was immobilized on magnetic beads. As shown in Fig. 3B, p65/Re1A associates with the wild type but not with the NF-κB-mutated promoter, indicating specific binding. As with the in vivo experiments, similar amounts of the TFIID components TAFII250 and TBP were associated with the A20 promoter in the presence or absence of p65/Re1A, confirming that NF-κB transcriptional activity is not directed to TFIID recruitment. Also, p65/Re1A had no detectable effect on Sp1 association with the A20 promoter in this assay.

FIG. 3.

Sp1 enhances recruitment of TFIID to the A20 promoter. (A) Schematic representation of A20 promoter organization and the mutated promoters used for the subsequent experiments. (B) NF-κB does not change core promoter occupancy by TFIID in vitro. DNA fragments of wild-type (WT) and NF-κB-mutated promoter were immobilized on magnetic beads and used for a binding reaction with Jurkat nuclear extract supplemented with purified recombinant p65/Re1A. The bound proteins were eluted from the beads and analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against p65/Re1A, TBP, and TAFII250. (C) DNA binding by Sp1 is correlated with increased TFIID association with the A20 promoter. Immobilized template-binding reactions with wild-type and Sp1-mutated A20 promoter and Jurkat cell nuclear extract prepared from nonstimulated cells are shown.

FIG. 5.

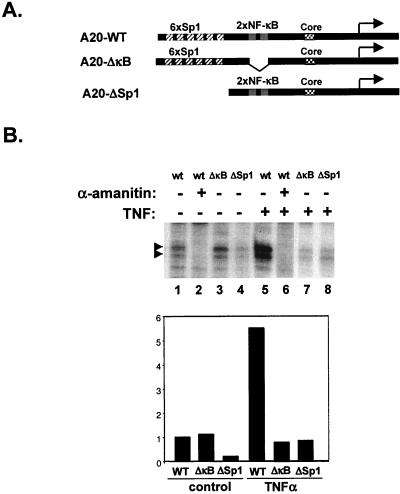

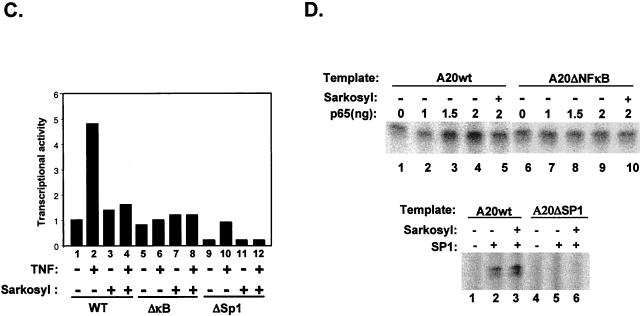

NF-κB increases the rate of transcription cycles. (A) Scheme of the A20 promoters used in the in vitro transcription assays. (B) In vitro transcription reactions were performed with nuclear extract prepared from either control (lanes 1 to 4) or 1-h-TNF-α-treated (lanes 5 to 8) Jurkat cells. The template used in each reaction is shown at the top of each lane. α-Amanitin (5 μM) was added to the reaction mixtures in lanes 2 and 6 to verify that the synthesized transcript is Pol II specific. In the lower panel, the transcription products were quantified by Phosphoimager and normalized to the noninducible cyclin A promoter activity. The noninduced wild-type (WT) promoter activity was set to 1. (C) In vitro transcription reactions with the respective A20 promoter plasmids (indicated at the bottom) and nuclear extract from untreated or TNF-α-treated Jurkat cells. In columns 3, 4, 7, 8, 11, and 12, Sarkosyl (0.2%) was added exactly 1.5 mins after the addition of nucleotides (see Materials and Methods). The results are presented as relative Phosphoimager measurements of the Pol II-specific transcript for each reaction. The noninduced wild-type promoter activity was set to 1. The amount of transcription extract used was normalized according to cyclin A promoter activity. (D) In the upper panel, transcription reaction mixtures were assembled with either wild-type or NF-κB site-mutated A20 promoter plasmids, as indicated at the top, nuclear extract from nonstimulated cells, and the indicated amounts of purified recombinant p65 homodimer. In the lower panel, purified Sp1 was added to the transcription reaction mixtures. To achieve the Sp1 effect, it was necessary to use smaller amounts of nuclear extract, and so the basal activity is not detected. These experiments are representative transcription assays, which were reproduced two to five times with similar results.

Given that NF-κB does not recruit TFIID and other basal transcription factors to the promoter, we asked how the transcription apparatus is brought to the promoter in unstimulated cells? One possibility was that another transcription factor(s) constitutively bound to the promoter renders the promoter accessible to the basal transcription machinery. Since the A20 promoter contains multiple binding sites for the constitutive transcription factor Sp1, we tested the possibility that Sp1 is involved in recruitment of TFIID to the promoter by applying the immobilized template-binding assay. We used nuclear extract from nonstimulated cells and either wild-type or Sp1-sites-deleted A20 promoter. As shown in Fig. 3C, Sp1 binds the wild-type A20 promoter but not the promoter lacking the Sp1 sites. Occupancy of the promoter by the TFIID subunits TBP and TAFII250 is correlated with Sp1 binding; as in the absence of Sp1, association of TBP and TAFII250 with the A20 promoter was reduced, suggesting that Sp1 is responsible for the enhancement of TFIID binding to the A20 promoter.

Sp1-mediated preinitiation complex formation is essential for rapid induction of the A20 gene.

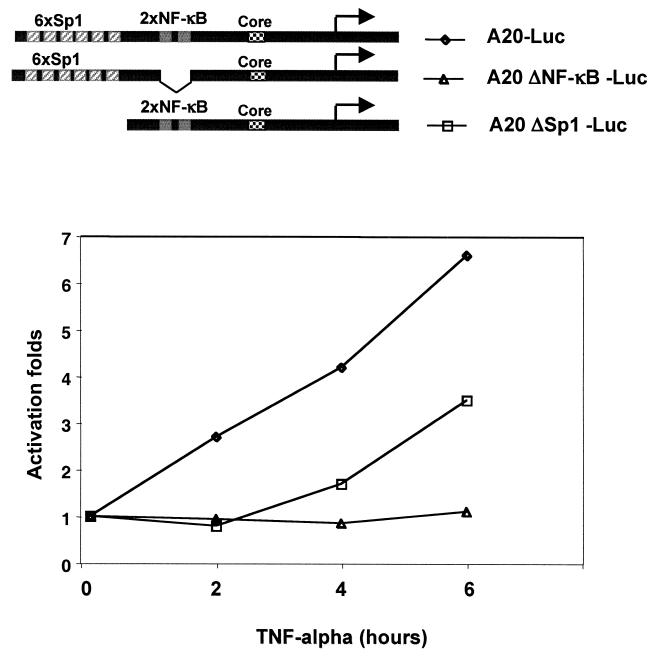

Previous studies have indicated that the process of preinitiation complex formation is slow (1, 29), implying that preoccupancy of the core promoter by the transcription machinery may be important for rapid transcriptional induction. Since Sp1 is responsible for recruitment of the transcription apparatus to the A20 promoter, we reasoned that interfering with its function would affect core promoter occupancy and induction of the A20 gene in response to TNF-α. To examine the role of Sp1 in the kinetics of the A20 promoter induction by TNF-α, all Sp1 sites were removed from the promoter and the TNF-α inducibility of the Sp1-mutated promoter was determined at different time points after induction and compared to that of the wild-type promoter. As shown in Fig. 4, the wild-type promoter was immediately induced upon TNF-α treatment whereas no induction was observed with a promoter lacking the two NF-κB sites, confirming that TNF-α induction is NF-κB mediated. Interestingly, the induction of the Sp1-deleted promoter was delayed and significantly inhibited, indicating that Sp1 is necessary for the rapid induction of the A20 gene. This dramatic effect of Sp1 may be explained by the fact that the core promoter of A20 does not contain a TATA box and, in the absence of Sp1 binding, cannot efficiently associate with TFIID and the basal transcription machinery even in the presence of NF-κB. These findings suggest that recruitment of the transcription machinery to the promoter before NF-κB-activating signals is important for rapid induction of the A20 gene and further strengthen the observation that NF-κB activation is directed not to recruitment of the basal transcription machinery but to a subsequent step.

FIG. 4.

Sp1 is required for rapid transcriptional induction of the A20 promoter. Luciferase reporter genes under the control of wild-type A20 promoter (A20-Luc) or a promoter that is mutated in either NF-κB or Sp1 site (A20-LucΔNF-κB and A20-LucΔSp1, respectively) were transfected into human 293 cells. A schematic representation of the promoter constructs is shown in the upper panel. At 16 h after transfection, TNF-α was added to the cells for the indicated time points and luciferase activity was measured. For each of the reporter constructs, the noninduced activity was set to 1. This is a representative experiment of three independent transfection experiments (done in duplicate), which gave similar results.

NF-κB activity is directed to enhancement of transcription reinitiation.

To investigate the mechanism of activation by NF-κB, transcription from the A20 promoter was reconstituted in vitro using nuclear extract from either control or 1-h-TNF-α-treated Jurkat cells. The correctly initiated transcript was monitored by a primer extension assay, which was expected to yield a 92-nucleotide cDNA. As shown in Fig. 5B, transcription from the A20 promoter was 5.5-fold higher with extract prepared from TNF-α treated cells than with extract from untreated cells (lanes 1 and 5 and lower panel). This transcript was sensitive to 5 μM α-amanitin, confirming that it is generated by Pol II (lanes 2 and 6). As in the transfection experiments, the TNF-α-induced transcript was both NF-κB and Sp1 dependent, since mutations in these sites severely reduced transcription (lanes 7 and 8 and lower panel). The noninduced basal transcription directed by the control extract was dependent on Sp1 (lane 4) but not NF-κB (lane 3), a result consistent with Sp1 being a constitutive transcription factor. As a control, transcription reactions with these extracts were carried out with a non-TNF-α-responsive promoter, the cyclin A promoter, which was used to normalize for the A20 promoter activity (histogram, lower panel).

Since the mechanism of transcriptional activation by NF-κB is not directed to enhancement of preinitiation complex formation, it is possible that NF-κB activity is not associated with the initiation step but is required for a postinitiation step such as reinitiation. To test the effect of TNF-α/NF-κB on transcription reinitiation, the detergent Sarkosyl was used because it can inhibit initiation but not elongation (33). If Sarkosyl is added immediately after initiation, it allows completion of the already initiated transcripts but prevents subsequent transcription cycles. As shown in Fig. 5C, the TNF-α-induced activity which is NF-κB dependent is sensitive to Sarkosyl (compare columns 2 and 4) whereas the noninduced activity which is directed by Sp1 is not sensitive to Sarkosyl (compare columns 1 and 3). (In fact, we have reproducibly observed a slight increase in transcription upon addition of Sarkosyl to the NF-κB-independent transcription, which might be related to an effect on transcription elongation.) When an NF-κB-mutated promoter was used with either noninduced or induced extracts, Sarkosyl did not decrease the transcription (columns 5 to 8), whereas the residual transcription directed by the Sp1 site-deleted promoter which is TNF-α inducible was eliminated by sarkosyl (columns 9 to 12). These results suggest that Sp1 is required for the initiation step and NF-κB is required for multiple transcription rounds.

To further confirm the differential effects of NF-κB and Sp1 on the A20 promoter, purified recombinant NF-κB protein p65/Re1A or Sp1 was added to the nonstimulated nuclear extract. As shown in Fig. 5D, p65/Re1A activated the wild-type but not NF-κB site-mutated A20 promoter in a dose-dependent manner and this activation was inhibited by Sarkosyl (lanes 4 and 5), supporting the idea that NF-κB transcriptional activity is directed, at least in part, to the enhancement of the reinitiation rate. Addition of purified Sp1 protein to the extract stimulated wild-type but not Sp1-mutated A20 promoter activity, but unlike p65/Re1A, Sp1 activity was not inhibited by Sarkosyl, confirming that Sp1 enhances the efficiency of transcription initiation. Together, these results indicate that on the A20 promoter, Sp1 activity is directed to the initiation step while NF-κB activity enhances the reinitiation rate.

DISCUSSION

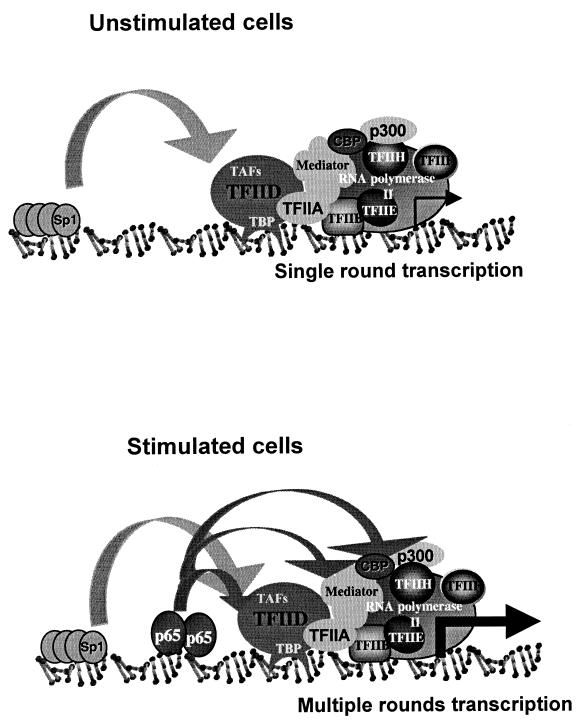

In this study we have investigated the molecular mechanism of transcriptional induction of NF-κB target genes in vivo in their native chromatin context and in vitro using the A20 gene as a prototype NF-κB target. On the basis of the results, we suggest a model that is illustrated schematically in Fig. 6. The promoters of a subset of NF-κB-regulated genes are accessible to binding by the basal transcription apparatus through the action of a constitutively active transcription factor. This complex remains bound but essentially inert until certain extracellular signals promote the nuclear transport of NF-κB, which then associates with NF-κB-binding sites on the target genes. Under unstimulated conditions, transcription from these promoters can initiate but the rate of reinitiation is low, resulting in small amounts of transcripts. In stimulated cells, NF-κB functions to increase the rate of transcription rounds, resulting in a high level of transcription. This model was based on the analysis of the A20 promoter, but it is likely that a similar mechanism is used by other NF-κB-regulated promoters since three additional NF-κB target promoters were found associated with the general transcriptional apparatus in the absence of NF-κB. Since promoters are organized differently, the recruitment of the general transcription machinery may be mediated by another constitutively active transcription factor(s) that may cooperate with NF-κB in a similar manner to Sp1.

FIG. 6.

Model for transcriptional induction of NF-κB-responsive genes. In unstimulated cells, the promoters of NF-κB target genes are pre-occupied by the general transcription apparatus due to the function of a constitutively active transcription factor such as Sp1 that acts to recruit TFIID to the promoter. This complex is inadequate for multiple transcription rounds and thus can maintain only a low level of basal transcription. In stimulated cells, the association of NF-κB with the promoter is followed by multiple contacts with components of the transcription apparatus such as the TAF subunits, CBP, p300, and Mediator. These interactions promote multiple transcription cycles, resulting in high level of transcription.

Assigning different but essential roles to the NF-κB and Sp1 transcription factors in regulating A20 transcription explains the synergy observed between these two factors that is required for the elevated transcription as well as the rapid response of this gene to TNF-α. It is possible that differential effects of transcription factors on the transcription steps may also be linked to the context of the core promoter since the A20 promoter lacks a canonical TATA box and a sequence resembling the initiator around the initiation site. Furthermore, these findings support the notion that different classes of activation domains can be divided into groups that influence distinct steps of the transcription process, i.e., recruitment of chromatin-remodeling activities, recruitment of basal transcription factors, recruitment of coactivators, enhancement of initiation and reinitiation rates, transcription elongation, and RNA processing. Consistent with this, Kim et al. have characterized the two activation domains of CREB (cyclic AMP-responsive element-binding protein) and found that the constitutive activation domain is required for preinitiation complex formation and the induced activation domain is required for multiple rounds of transcription (14).

Given that NF-κB forms important contacts with components of the general transcription apparatus such as the TFIID subunit TAFII105 (36, 37), the finding that the preinitiation complex constitutively associates with NF-κB-regulated promoters even in the absence of NF-κB implies that the NF-κB-TAFII105 interaction occurs on the promoter DNA rather than in the nucleoplasm. This might be the reason for our failure to detect any of the known NF-κB coactivators associated with the endogenous protein in nuclear extracts prepared from TNF-α-stimulated Jurkat cells (data not shown). Since the NF-κB activation function is directed to increase the rate of the transcription cycles, the association between NF-κB and TFIID subunits may be important for this effect, probably by facilitating the recruitment of the factors that were dissociated from the promoter on promoter clearance (38, 39). However, additional studies should be done to investigate the mechanism by which NF-κB enhances reinitiation. Since Sp1 is responsible for the initiation step on the A20 promoter and recruitment of TFIID to the promoter, these two functions are most probably linked. The recruitment of the substoichiometric TFIID containing TAFII105 to the A20 core promoter may involve a direct interaction between Sp1 and TAFII105 (data not shown) as well as with other TAFIIs.

Previous studies indicated that the kinetics of chromatin remodeling and preinitiation complex formation is slow even in the presence of an activator (1, 29). Thus, constitutive occupation of the promoter is a strategy that allows rapid transcriptional activation of genes that are required to provide an immediate response to extracellular signals. A similar strategy is used to regulate Drosophila heat shock genes (19) as well as other rapidly induced genes such as c-fos and c-myc. On these genes, Pol II has initiated but is stalled proximal to the initiation site (31). Like NF-κB, the activator of the heat shock genes, HSF, was found to control the reinitiation rate (27). Therefore, it will be interesting to examine whether in nonstimulated cells the subset of NF-κB-responsive genes examined here contain either stalled Pol II or prematurely terminated transcripts. The constitutive association of the transcription apparatus with NF-κB genes also implies that the chromatin organization of these genes is open and accessible to transcription factors. Whether this open chromatin configuration is achieved through the action of constitutively active transcription factors such as Sp1 has yet to be determined.

A20 is a zinc finger cytoplasmic protein expressed at a high level in lymphoid tissues. This factor is activated by NF-κB in response to proinflammatory signals such as TNF and functions to inhibit the inflammatory response and programmed cell death induced by these signals (17), thus reducing the damage that inflammation causes to tissues. Characterization of the important components, other than NF-κB, regulating this and other genes involved in the inflammatory process may help find additional and more specific targets for drugs that interfere with the inflammatory process.

Acknowledgments

E. Ainbinder, M. Revach, and O. Wolstein contributed equally to this work.

This research was supported by grants from the Israel Science Foundation and the Israel Cancer Research Foundation. Rivka Dikstein is incumbent of the Martha S. Sagon Career Development Chair.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agalioti, T., S. Lomvardas, B. Parekh, J. Yie, T. Maniatis, and D. Thanos. 2000. Ordered recruitment of chromatin modifying and general transcription factors to the IFN-beta promoter. Cell 103:667-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albright, S. R., and R. Tjian. 2000. TAFs revisited: more data reveal new twists and confirm old ideas. Gene 242:1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berk, A. J. 1999. Activation of RNA polymerase II transcription. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 11:330-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carey, M., Y. S. Lin, M. R. Green, and M. Ptashne. 1990. A mechanism for synergistic activation of a mammalian gene by GAL4 derivatives. Nature 345:361-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dikstein, R., S. Zhou, and R. Tjian. 1996. Human TAFII105 is a cell type-specific TFIID subunit related to hTAFII130. Cell 87:137-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerritsen, M. E., A. J. Williams, A. S. Neish, S. Moore, Y. Shi, and T. Collins. 1997. CREB-binding protein/p300 are transcriptional coactivators of p65. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:2927-2932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grunstein, M. 1990. Histone function in transcription. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 6:643-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guermah, M., S. Malik, and R. G. Roeder. 1998. Involvement of TFIID and USA components in transcriptional activation of the human immunodeficiency virus promoter by NF-kappaB and Sp1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:3234-3244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoey, T., R. O. Weinzierl, G. Gill, J. L. Chen, B. D. Dynlacht, and R. Tjian. 1993. Molecular cloning and functional analysis of Drosophila TAF110 reveal properties expected of coactivators. Cell 72:247-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffmann, A., T. Oelgeschlager, and R. G. Roeder. 1997. Considerations of transcriptional control mechanisms: do TFIID-core promoter complexes recapitulate nucleosome-like functions? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:8928-8935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsu, S. C., M. A. Gavrilin, H. H. Lee, C. C. Wu, S. H. Han, and M. Z. Lai. 1999. NF-kappa B-dependent Fas ligand expression. Eur. J. Immunol. 29:2948-2956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito, C. Y., A. G. Kazantsev, and A. S. Baldwin. 1994. Three NF-kappa B sites in the I kappa B-alpha promoter are required for induction of gene expression by TNF alpha. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:3787-3792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasibhatla, S., T. Brunner, L. Genestier, F. Echeverri, A. Mahboubi, and D. R. Green. 1998. DNA damaging agents induce expression of Fas ligand and subsequent apoptosis in T lymphocytes via the activation of NF-kappa B and AP-1. Mol. Cell 1:543-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim, J., J. Lu, and P. G. Quinn. 2000. Distinct cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) domains stimulate different steps in a concerted mechanism of transcription activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:11292-11296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krikos, A., C. D. Laherty, and V. M. Dixit. 1992. Transcriptional activation of the tumor necrosis factor alpha-inducible zinc finger protein, A20, is mediated by kappa B elements. J. Biol. Chem. 267:17971-17976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Bail, O., R. Schmidt-Ullrich, and A. Israel. 1993. Promoter analysis of the gene encoding the I kappa B-alpha/MAD3 inhibitor of NF-kappa B: positive regulation by members of the rel/NF-kappa B family. EMBO J. 12:5043-5049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee, E. G., D. L. Boone, S. Chai, S. L. Libby, M. Chien, J. P. Lodolce, and A. Ma. 2000. Failure to regulate TNF-induced NF-kappaB and cell death responses in A20-deficient mice. Science 289:2350-2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin, Y. S., M. Carey, M. Ptashne, and M. R. Green. 1990. How different eukaryotic transcriptional activators can cooperate promiscuously. Nature 345:359-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lis, J., and C. Wu. 1993. Protein traffic on the heat shock promoter: parking, stalling and trucking along. Cell 74:1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naar, A. M., P. A. Beaurang, S. Zhou, S. Abraham, W. Solomon, and R. Tjian. 1999. Composite co-activator ARC mediates chromatin-directed transcriptional activation. Nature 398:828-832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Opipari, A. W., M. S. Boguski, V. M. Dixit. 1990. The A20 cDNA induced by tumor necrosis factor alpha encodes a novel type of zinc finger protein. J. Biol. Chem. 265:14705-14708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orphanides, G., T. Lagrange, and D. Reinberg. 1996. The general transcription factors of RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 10:2657-2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orlando, V., H. Strutt, and R. Paro. 1997. Mapping protein distribution in chromatin structure by in vivo formaldehyde cross-linking. Methods: Companion Methods Enzymol. 11:205-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pahl, H. L. 1999. Activators and target genes of Re1/NF-κB transcription factors. Oncogene 18:6853-6866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perkins, N. D., N. L. Edwards, C. S. Duckett, A. B. Agranoff, R. M. Schmid, and G. J. Nabel. 1993. A cooperative interaction between NF-kappa B and Sp1 is required for HIV-1 enhancer activation. EMBO J. 12:3551-3558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinaud, S., and J. Mirkovitch. 1998. Regulation of c-fos expression by RNA polymerase elongation competence. J. Mol. Biol. 280:785-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sandaltzopoulos, R., and P. B. Becker. 1998. Heat shock factor increases the reinitiation rate from potentiated chromatin templates. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:361-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sauer, F., S. K. Hansen, and R. Tjian. 1995. Multiple TAFIIs directing synergistic activation of transcription. Science 270:1783-1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shang, Y., X. Hu, J. DiRenzo, M. A. Lazar, and M. Brown. 2000. Cofactor dynamics and sufficiency in estrogen receptor-regulated transcription. Cell 103:843-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silkov, T., O. Wolstein, I. Shachar, and R. Dikstein. 2002. Enhanced apoptosis in B and T lymphocytes in TAFII105 dominant negative transgenic mice is NF-kappaB dependent. J. Biol. Chem. 277:17281-17829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spencer, C. A., and M. Groudine. 1990. Transcription elongation and eukaryotic gene regulation. Oncogene 5:777-785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thanos, D., and T. Maniatis. 1992. The high mobility group protein HMG I(Y) is required for NF-kappa B-dependent virus induction of the human IFN-beta gene. Cell 71:777-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tolunay, H. E., L. Yang, W. F. Anderson, and B. Safer. 1984. Isolation of an active transcription initiation complex from HeLa cell-free extract. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:5916-5920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolf, I., V. Pevzner, E. Kaiser, G. Bernhardt, E. Claudio, U. Siebenlist, R. Forster, and M. Lipp. 1998. Downstream activation of a TATA-less promoter by Oct-2, Bob1, and NF-kappaB directs expression of the homing receptor BLR1 to mature B cells. J. Biol. Chem. 273:28831-28836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu, M. X., Z. Ao, K. V. Prasad, R. Wu, and S. F. Schlossman. 1998. IEX-1L, an apoptosis inhibitor involved in NF-kappaB-mediated cell survival. Science 281:998-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamit-Hezi, A., and R. Dikstein. 1998. TAFII105 mediates activation of anti-apoptotic genes by NF-kappaB. EMBO J. 17:5161-5169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamit-Hezi, A., S. Nir, O. Wolstein, and R. Dikstein. 2000. Interaction of TAFII105 with selected p65/Re1A dimers is associated with activation of subset of NF-κB genes. J. Biol. Chem. 275:18180-18187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yudkovsky, N., J. A. Ranish, and S. Hahn. 2000. A transcription reinitiation intermediate that is stabilized by activator. Nature 408:225-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zawel, L., K. P. Kumar, and D. Reinberg. 1995. Recycling of the general transcription factors during RNA polymerase II transcription. Genes Dev. 9:1479-1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]