Abstract

Objective:

We sought to compare the efficacy, risks, and costs of whole-organ pancreas transplantation (WOP) with the costs of isolated islet transplantation (IIT) in the treatment of patients with type I diabetes mellitus.

Summary Background Data:

A striking improvement has taken place in the results of IIT with regard to attaining normoglycemia and insulin independence of type I diabetic recipients. Theoretically, this minimally invasive therapy should replace WOP because its risks and expense should be less. To date, however, no systematic comparisons of these 2 options have been reported.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective analysis of a consecutive series of WOP and IIT performed at the University of Pennsylvania between September 2001 and February 2004. We compared a variety of parameters, including patient and graft survival, degree and duration of glucose homeostasis, procedural and immunosuppressive complications, and resources utilization.

Results:

Both WOP and IIT proved highly successful at establishing insulin independence in type I diabetic patients. Whole-organ pancreas recipients experienced longer lengths of stay, more readmissions, and more complications, but they exhibited a more durable state of normoglycemia with greater insulin reserves. Achieving insulin independence by IIT proved surprisingly more expensive, despite shorter initial hospital and readmission stays.

Conclusion:

Despite recent improvement in the success of IIT, WOP provides a more reliable and durable restoration of normoglycemia. Although IIT was associated with less procedure-related morbidity and shorter hospital stays, we unexpectedly found IIT to be more costly than WOP. This was largely due to IIT requiring islets from multiple donors to gain insulin independence. Because donor pancreata that are unsuitable for WOP can often be used successfully for IIT, we suggest that as IIT evolves, it should continue to be evaluated as a complementary alternative to rather than as a replacement for the better-established method of WOP.

Whole-organ pancreas and isolated islet transplantation are competing strategies for the treatment of type I diabetes. We compared the results of a consecutive series of vascularized pancreas transplants with a contemporaneous consecutive series of isolated islet transplants. The results suggest that at present, these therapies should be considered complementary.

Type I diabetes mellitus afflicts nearly 2 million Americans and is responsible for untold morbidity. Despite significant improvements in monitoring and administration, insulin therapy cannot fully normalize glucose homeostasis at the present time. Therefore, curative therapies for the disease have relied on replacement of the β-cell mass by transplantation. During the last 35 years, whole organ pancreas transplantation (WOP) has evolved gradually into a highly effective therapy for type I diabetic patients who are undergoing simultaneous renal transplantation.1–5 Because the risks of severe complications of this procedure are relatively small in these patients who are already obligated to lifelong immunosuppression, the benefits of the procedure are generally accepted as outweighing the risks.6 In recent years, WOP has also been advocated for type 1 patients with diabetes who have either adequate function of their own kidneys or an established renal transplant. In these cases of pancreas transplant alone or pancreas after kidney transplantation (PAK), very poor glucose control and dangerous episodes of hypoglycemic unawareness are the usual and most persuasive indications for transplantation. These pancreas without kidney transplants remain controversial despite the success of the simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplant procedure (SPK), with at least one recent analysis suggesting that the risks of these procedures may outweigh their benefits.7

IIT offers a less invasive and thus presumably less morbid alternative to WOP for β-cell replacement, although the success of this procedure was considered exceedingly rare until relatively recently.8 By the 1990s, a number of centers using improved methods of islet isolation demonstrated that IIT quite often resulted in sustained insulin secretion. Nevertheless, insulin independence at 1 year post-transplantation remained unusual (<10%).9,10 In 2000, investigators from Edmonton reported achieving insulin independence in 7 consecutive IIT recipients.11 Their innovative approach entailed retreating partially successful transplant recipients (C-peptide-positive but not insulin-free) with a second or third infusion of islets from additional donors. Since this landmark study, a number of other centers have confirmed the Edmonton results in small series of patients, including at least 2 that reported success with islets from single donors.12,13 In the largest concerted effort to replicate the results of Edmonton, the National Institutes of Health–supported “Immune Tolerance Network” mandated 9 centers to transplant a total of 40 patients following a protocol identical to Edmonton's. Preliminary reports of this trial indicate that in the 3 most experienced sites, insulin independence was achieved in >90% of patients.14 However, in the other 6 centers, success was sporadic (0–50%), probably due to the complexity of the isolation technique and the need for additional experience.15

The success and relative safety of the Edmonton trial has led some to suggest that IIT is ready to supersede WOP as the procedure of choice for replacement of β-cells in type I diabetic patients. Such a contention has important implications in schemas for cadaveric pancreas organ use, because candidates for WOP are currently given priority over potential IIT recipients. Thus, it is important to compare the 2 transplant methods. We have examined a contemporary series of WOP and IIT at our institution to compare relative efficacy, safety, and cost.

METHODS

WOP

Between October 5, 2001 and February 25, 2004, 30 vascularized WOPs, including 25 SPKs and 5 PAKs, were performed at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. Exocrine drainage was managed by jejunal loop in 29 cases and by bladder drainage in 1 case. WOP grafts were transplanted with systemic venous drainage in 13 cases and with portal drainage in 17 cases. Immunosuppression for WOP consisted of induction with thymoglobulin and maintenance with triple-drug therapy comprising tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and steroids.

Pancreatic Islet Isolation

Pancreatic islets were isolated only from cadaveric organ donors that had been deemed unsuitable for and declined for use in WOP by using a modified Ricordi method, as previously described in detail.16–18 Relative islet mass was estimated by normalization of the size of counted islets to an average size of 150 μm. Product release criteria for transplantation included the following: 1) Gram stain–negative for bacteria, (2) purity >30%, (3) viability >70%, (4) islet mass >4000 IEQs/kg recipient, (5) endotoxin content <5 EU/kg of recipient, and (6) a packed tissue volume <10 mL. Post-transplantation evaluation of islets included functional assessment by glucose-stimulated insulin release perifusion and sterility testing. In 4 cases, islets prepared from 2 separate cadaveric donors were transplanted as a single infusion.

IIT

Between September 21, 2001 and February 11, 2004, 13 type I diabetic patients underwent IIT, 9 as islet transplant alone (ITA) and 4 as islet after kidney transplants (IAK). All ITA patients had highly labile diabetes complicated by repeated episodes of severe hypoglycemic unawareness as the indication for transplantation. ITA patients were treated identically to the Edmonton regimen, ie, induction therapy with Zenapax 2 mg/kg × 1 dose, then 1 mg/kg/2 weeks × 4 doses, and with maintenance tacrolimus (target level 2–5 ng/mL) and rapamycin (target trough 12–15 ng/mL). IAK patients were previously transplanted with a renal allograft and had stable graft function with creatine clearances (CrCl) ≥ 55 mL/min. Each had a PRA = 0, and had not had a rejection episode for at least 6 months. One of the ITA patients was withdrawn from the study before completing treatment after a traumatic foot injury that required surgery and demonstrated poor healing, mandating discontinuation of immunosuppression. The patient was excluded from the graft survival analysis but is included in the complication and resource analysis.

Resource Utilization Analysis

The institution's financial database was used to provide information on length of stay in the hospital and intensive care unit and on direct costs. Analyses were conducted to compare resource use for WOP with that for IIT. The 4 most recent pancreas transplants and 1 islet transplant were excluded from direct cost analysis because insufficient time had elapsed for reliable capture of all financial data. Data was analyzed for inpatient direct costs associated with both admission for transplantation and subsequent readmissions for the entire duration of the study. The median duration of follow-up was comparable for the groups (421 days for WOP vs 522 days for IIT, P value not significant).

Because the majority of WOP patients also received a simultaneous renal transplant, a further analysis was performed in which the costs attributable to renal allograft per se were excluded (eg, the cost of the donor kidney, 33% of the operating room charges, and postoperative care specific to the kidney transplant). In the 4 cases of pancreas-alone transplants (all PAKs), costs could be compared directly to the results for IIT. Finally, for IITs, a separate intent to transplant analysis was performed to account for the costs of pancreatic islet isolations that had been initiated for the purposes of clinical transplantation but that did not result in islets meeting release criteria for transplantation and thus were not used clinically (about 50%). For these isolations, our Organ Procurement Organization granted us a discounted price for the pancreas that was about 10% of the cost of a pancreas transplanted as a WOP or one that yielded islets that were transplanted.

Statistical Analyses

Kaplan-Meier graft survival was calculated with SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Group means were compared by independent sample t tests and nominal data by χ2 analysis. P values > 0.05 were defined as not statistically significant.

RESULTS

Program Activity in IIT

Between February 8, 2000 and February 11, 2004, 202 cadaveric pancreata were processed for isolated islets at our center. The first 96 isolations were performed before we began clinical transplantation to standardize an efficient isolation technique. Isolations for the purpose of clinical transplantation began in September 2001. Of the subsequent 106 isolations, 52 were conducted with the intent to transplant and the remaining 54 were performed for a variety of reasons, including process quality control, improvement and validation, team training, and β-cell–related research. Of the 52 isolations performed with the intent to transplant, 27 produced a quantity and quality of islets justifying transplantation; the other 25 preparations did not meet transplant release criteria for the following reasons: 7 had insufficient yield after digestion, 8 had insufficient yield after purification, and 10 had insufficient quality. No preparations failed release criteria based on poor viability (all >90% viability) or endotoxin levels exceeding the 5 EU/kg limit.

For infused preparations, the average number of islet equivalents (IEQ)/infusion was 551,100 (range 293,600–881,700 or 8440 IEQ/kg per recipient) and the total infused per patient was 15,475 IEQ/kg. Ultrasound localization and percutaneous transhepatic cannulation of portal vein branches under angiographic guidance was used for 22 of 23 islet infusions. The most recent infusion was performed by mini-laparotomy with cannulation of a portal tributary in the omentum. In this case, an 8F pediatric feeding tube was advanced into a portal vein branch, and contrast fluoroscopy was employed to document the proper position of the catheter. With both approaches, portal pressures were monitored every 5 minutes during the infusion.

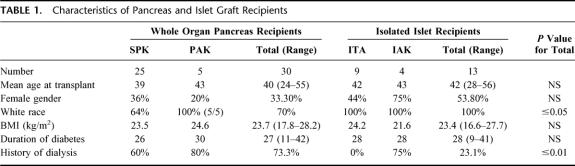

Comparison of WOP Recipients With IIT Recipients (Table 1)

TABLE 1. Characteristics of Pancreas and Islet Graft Recipients

WOP and IIT recipients were similar in terms of age, gender, body mass index, and duration of diabetes. As expected based on study design, there was a marked difference in the proportion of patients who had been previously treated by dialysis in the WOP group.

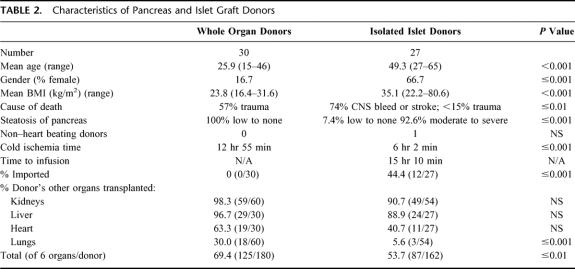

Comparison of WOP Donors With IIT Donors (Table 2)

TABLE 2. Characteristics of Pancreas and Islet Graft Donors

In accordance with standard United Network for Organ Sharing guidelines, cadaveric donor pancreata were allocated first for vascularized WOP. As a result, all pancreata used for IIT had been rejected for use as WOP. The most frequent reason for rejection of a donor pancreas for WOP was a donor age of 50 years or more, and for pancreata from donors <50 years it was organ steatosis. Thus, in general, islet donors were older and heavier. The more marginal quality of the islet donors was further suggested by the finding that other vital organs from these donors (kidney, liver, heart, and lung) were less often transplanted than in the case of WOP donors. Despite the more frequent use of pancreata imported from outside the local Organ Procurement Organization for IIT, mean cold ischemia time for IIT was significantly less than for WOP (362 vs 776 minutes, respectively, P < 0.001). The mean time from donor cross clamp to islet infusion was 916 minutes (ie, the cold ischemia time plus the time required for processing, analysis, and infusion) and significantly longer than cold ischemia time for WOP (P ≤ 0.003).

Patient and Graft Survival After WOP and IIT

One of 30 whole-organ pancreas recipients died of unknown causes but with good graft function at 11 days after discharge from an uneventful SPK (4 weeks post-transplantation). An autopsy was not performed. Two grafts were lost from vascular thrombosis on post-operative days (PODs) 4 and 6. One graft was lost from persistent perigraft infection at 1 month post-transplantation and one was lost to rejection at 24 months. Twenty-five of 30 pancreatic graft patients continued to function normally.

Of 12 islet recipients completing treatment, all but 1 became insulin independent. The patient who never became insulin independent received 3 separate infusions, and the insulin requirement decreased substantially (76 to 15 U/d) and still has evidence of significant C-peptide secretion. This patient was subsequently found to have high levels of anti-insulin autoantibodies, possibly explaining his atypical response to islet transplantation. In 1 of the 11 patients achieving insulin independence, immunosuppression was withdrawn when the patient developed painful mouth ulcers, leading to self-discontinuation of Rapamune. The graft rapidly failed and C-peptide was undetectable 3 months later. Two of the remaining 10 patients who became insulin independent have subsequently completely lost graft function after 525 and 550 days, as assessed by an absence of C-peptide production.

Gradual deterioration in graft function and persistent mild fasting hyperglycemia led to reinstitution of small doses of insulin (4–9 units) in 3 additional patients. In each of these cases, continued islet transplant survival is evident from ongoing C-peptide production, in graft function during periodic mixed-meal challenges, and in greatly reduced insulin requirements compared with pretransplant doses. Five patients remain normoglycemic and completely insulin independent from 3 months to 2.5 years post-transplantation. Importantly, none of the patients with graft function (even if partial) have experienced hypoglycemic episodes after IIT. Because dangerous episodes of hypoglycemic unawareness were the indications for the majority of transplants, this outcome is particularly gratifying.

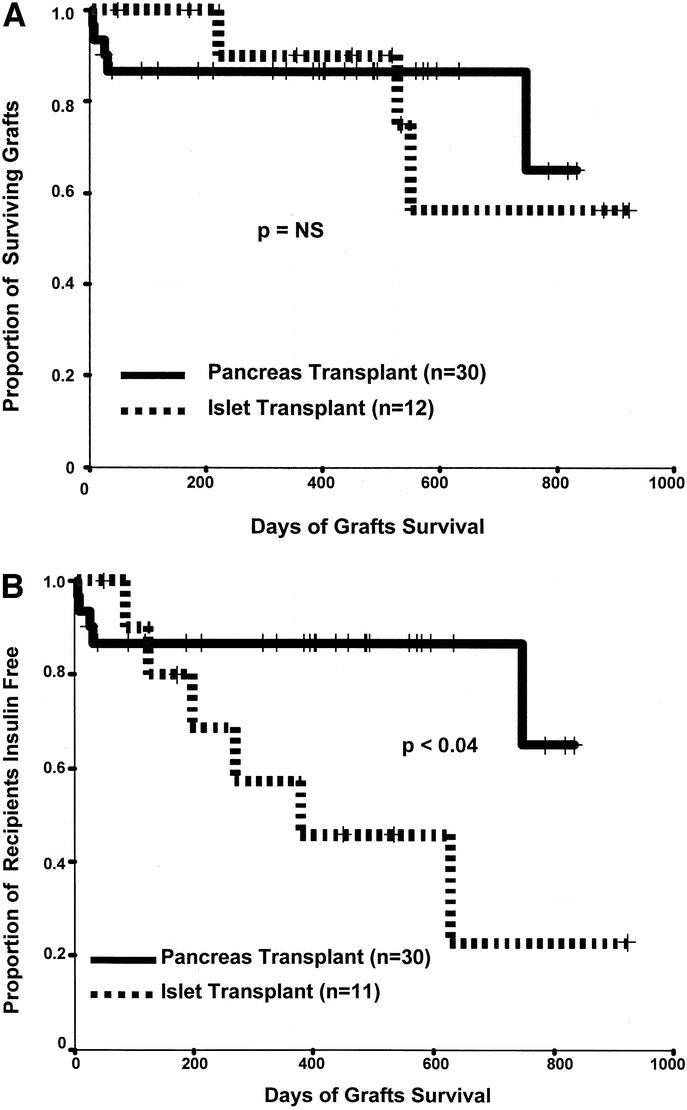

By Kaplan-Meier analysis, no statistical difference was evident comparing patient and graft survival after WOP versus IIT (Fig. 1a). WOP was statistically superior to IIT (evidenced by C-peptide levels, HgA1C%, and insulin requirements) and in the duration of insulin independence achieved if partially functioning islet grafts were included (Fig. 1b).

FIGURE 1. A Kaplan-Meier graft survival (a) and insulin independence (b) comparing WOP recipients and IIT recipients. One islet recipient was excluded from graft survival analysis because he or she was withdrawn from the study before completing the treatment protocol. The death in the pancreas transplant group is counted as an early graft lost. Graft loss in islet recipients was defined as a persistent C-peptide level <0.5 ng/mL and a return to pretransplant levels of insulin requirement. For the insulin-free survival analysis, 2 islet recipients were excluded from the curve, ie, the patient mentioned above who withdrew from the study after a single partially effective infusion and the patient who received 3 infusions but did not gain insulin independence.

Islet Function After Successful WOP and IIT

To assess relative IIT and WOP function post-transplantation, we compared fasting C-peptide levels. For IIT patients, serial levels of C-peptide were determined, whereas for WOP recipients only a single measurement was routinely obtained postoperatively. WOP recipients generally exhibited higher C-peptide levels than islet recipients during the first 600 days after transplantation (3.9 vs 1.7 ng/mL, respectively, P < 0.001). Mean C-peptide levels in insulin-independent islet recipients were higher than in patients requiring small doses of insulin (2.3 vs 1.1 ng/mL, P value not statistically significant); however, neither group exhibited levels comparable to WOP recipients.

As a further index of chronic glucose homeostasis, hemoglobin A1c levels were monitored. Glucose control was superior in WOP recipients than in IIT during the first year post-transplantation (HbA1c 5.0% vs 6.3%, P ≤ 0.001). Paralleling the results for C-peptide production, HgA1c in insulin-independent islet recipients was less than that in patients requiring small doses of insulin (5.6% vs 6.65%, P value not statistically signficant), but neither group matched the levels obtained after WOP.

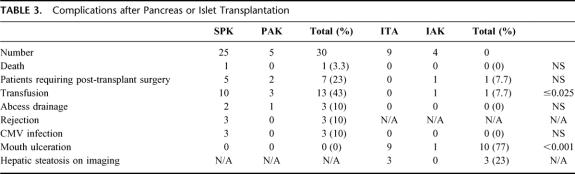

Complications of WOP and IIT (Table 3)

TABLE 3. Complications after Pancreas or Islet Transplantation

In general, complications related to the WOP procedure were more severe than those related to IIT. There was one death after pancreas transplantation and none after islet transplantation. Ten surgeries to address transplant-related complications were required in 7 of 30 WOP recipients, including 3 patients requiring graft pancreatectomy. An operative intervention was required in 1 islet recipient to evacuate a hemothorax.

Blood Loss Requiring Transfusion

Pancreas transplant recipients were more likely than islet recipients to require blood transfusion during the transplant admission (13 WOP recipients required a total of 46 units of packed red blood cells). Although percutaneous transhepatic islet infusion was associated with 3 bleeding events out of 22 infusions, only 1 was significant enough to require intervention. In 2 patients, small intraperitoneal bleeds occurred that were evident on computed tomography imaging but resolved spontaneously. The third case resulted in a significant hemothorax that required transfusion of 6 units of packed red blood cells and a thoracoscopic evacuation of a residual clot not adequately drained by a thoracostomy tube.

REJECTION

Graft rejection was observed in 6 SPK patients; 3 cases primarily involved the kidney and the other 3 primarily involved the pancreas. No reliable markers for islet rejection are available, and thus our study protocol prohibited specific antirejection therapy. It seems likely that rejection was responsible for graft loss in a single patient who discontinued his immunosuppression because of mouth ulcers.

Immunosuppression-Related Adverse Events

A variety of immunosuppression-related adverse events were recorded in islet recipients as part of Federal Drug Administration–mandated adverse event reporting for this clinical trial. The most frequent adverse event was rapamycin-related mouth ulceration, which was observed in all 9 ITA patients and in 1 of 4 IAK patients. Interestingly, 3 of 4 IAK patients who did not exhibit mouth ulceration were the only islet recipients receiving chronic low-dose steroids (prednisone 5 mg/day). The single ITA patient who discontinued rapamycin had particularly severe mouth ulceration that involved the hard palate and hypopharynx.

Other immunosuppression-related adverse events included a variety of blood count abnormalities including anemia in all but 2 recipients, mild leucopenia in 6 recipients, and mild thrombocytopenia in 5 recipients. Lower extremity edema occurred in 54% of the islet patients and lipid abnormalities requiring statin therapy occurred in 23%. The most serious opportunistic infection recorded was cytomegalovirus, which required treatment in 3 pancreas transplant recipients but was not seen in the islet recipients. Malignancy was not seen except in a single islet patient who underwent resection of an in situ squamous cell of the back at 30 months post-transplantation.

Renal function was followed carefully in ITA patients with Crcl measurements every 3 months, because of the well-described nephrotoxic effects of calcineurin inhibitor therapy. Most recipients demonstrated a mild decline in their renal function, with a mean loss of Crcl of 16.5 mL/min per ITA recipient. The impact was highly variable; 2 ITA recipients manifested a small rise in their Crcl, whereas 2 others had a Crcl decline of greater than 35 mL/min.

Comparison of Resource Use After WOP and IIT

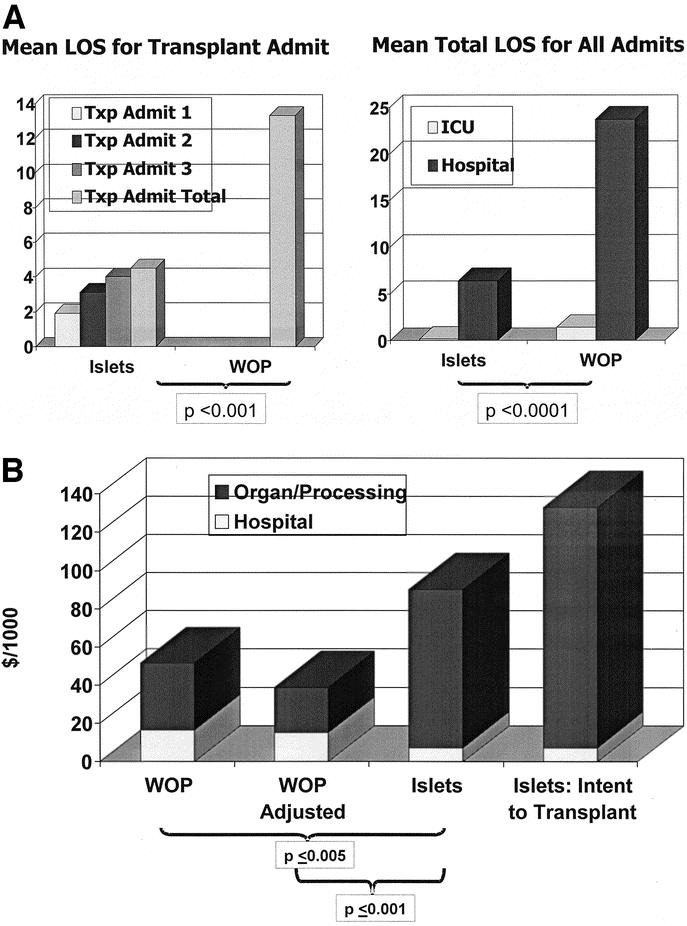

WOP was associated with a significantly longer length of stay in the hospital in the intensive care unit versus IIT both for transplant admission (Fig. 2a) and for all admissions during the follow-up period. The current data may underestimate these differences based on the fact that the hospital stay for islet patients is dictated not by medical necessity, but rather by research study requirements that mandate close observation and periodic laboratory testing for 36 hours.

FIGURE 2. Length of hospital stay for IIT recipients and WOP recipients (a). The islet patients had markedly fewer inpatient days than the pancreas recipients, both for their transplants and for their readmissions. This occurred despite the fact that most islet recipients underwent 2 or more infusions. Only 1 islet recipient required care in an intensive care unit, whereas the pancreas transplant recipients were routinely admitted to the intensive care unit immediately after transplantation. Figure 2b compares the direct cost of WOP with that of IIT. The unadjusted WOP cost includes all kidney-related charges for SPK recipients. The adjusted WOP cost subtracts all kidney-related charges to provide a more meaningful comparison with patients receiving islets but not kidney graft. Intent to transplant factors for islets include the organ and processing costs of the 23 pancreata that were processed with intent to clinically transplant but did not meet laboratory release criteria.

Comparison of mean direct costs accrued for the admission for transplantation demonstrated that costs for pancreas patients were significantly less than those for islet recipients (Fig. 2b). Because SPK patients received a kidney, a second analysis was performed in which costs directly attributable to the kidney portion of the procedure were deducted. This further magnified the direct cost difference between the groups. A separate analysis was conducted in which only PAK patients were compared with islet recipients (data not shown). In this way, the effect of confounding kidney-related charges in SPK recipients was avoided. The costs for PAK were not significantly different from the adjusted direct cost of SPK patients, but they were significantly less than those for islet recipients.

Finally, we applied an intent to transplant approach to account for the direct costs associated with pancreatic islet isolations that were performed for the purposes of clinical transplantation but that did not result in a transplantable preparation. Even though the pancreata for these cases were provided at a discounted rate, this led to a dramatic further increase in the direct cost of islet transplantation.

The direct costs for WOP and IIT were also broken down into hospital-related costs and costs associated with acquisition of the pancreas and its processing. As would be expected based on the above length-of-stay analysis, the hospital costs for WOP exceeded those for islets. This was, however, a relatively minor contribution to overall direct cost when compared with the enormous organ costs for the 2 groups. WOP used only one pancreas per recipient and had no additional organ processing charges unique to islet transplantation. Therefore, the cost for WOP comprised a fixed organ cost of about $20,000 and a more variable hospital cost.

The direct costs for processing a pancreas for islets has been shown to be slightly more than the cost of the organ itself, which is about $20,000. Total direct costs arising from pancreas processing mirror organ cost and increase incrementally with each pancreas processed. The full processing cost is incurred even if the pancreas does not result in a transplantable product. The additional organ processing–related cost per 12 recipients for 23 organs that were processed but unsuitable for infusion averaged over $40,000 per islet recipient.

DISCUSSION

The prospect that pancreatic islet transplantation would become an equally successful but less morbid alternative to vascularized whole-organ pancreas allografts was suggested by the initial reports of reversal in diabetes in experimental animal models more than 30 years ago.19,20 However, progress in treating human diabetes by this method has been slow. There is now a tendency to date the first success of islet transplants in humans to Shapiro's landmark report in 2000 of 7 patients who became insulin free after islet transplantation.11 However, this ignores the considerable progress that was made during the previous decade, much of it attributable to advances in the technique of islet isolation by Ricordi.16,17 Encouraging reports of at least temporary islet graft survival had been made by numerous investigators.21–24 In fact, the International Islet Transplant Registry reported the worldwide 1-year graft survival rate (by C-peptide secretion) of 1990–1993 islet transplants to be 38%, which improved by 1998–1999 to 68%. Nevertheless, less than 10% of these patients were ever completely insulin independent.9

The strikingly better results of the initial Edmonton report naturally posed the question of whether IIT was ready to replace WOP in all diabetic patients for whom replacement of islet mass was indicated. A demonstration of consistent success and the presumption of lower costs and fewer complications of this minimally invasive method would in fact be logical arguments for broadening the indications for transplantation to include most patients with diabetes. It therefore seemed pertinent to us to compare the reliability, safety, durability, and expense of IIT with the more established procedure of WOP performed contemporaneously in the same center.

Our study reinforces other recent reports that IIT to diabetic patients are capable of restoring glucose homeostasis quite consistently and with fewer serious complications than WOP.25,26 Perhaps more importantly, however, our experience highlights the barriers remaining and argues against premature acceptance of islet transplantation as the standard surgical therapy for type I diabetes. Specifically, our results demonstrate that although IIT is as reliable as WOP in the initial reversal of diabetes, IIT was likely to be associated with a shorter duration of complete insulin independence. Furthermore, even in the short term, insulin reserve and glucose control were inferior to that observed in WOP recipients. In addition, we found that islet transplantation as we performed it was substantially more costly than WOP, despite the latter being associated with longer hospitalization and with more serious and more frequent complications.

Recently, Venstrom et al used the United Network for Organ Sharing database to perform a study of the safety and risk benefit ratio for WOP patients compared with other diabetic patients listed for and awaiting WOP but never receiving it.7 They found that the risk of death was greater in patients who received pancreas transplant alone or PAK than in those who were listed but failed to receive a transplant. For SPK recipients, the benefit-to-risk ratio was highly favorable to transplantation, but in these patients the benefit of WOP could not be distinguished from the benefit of the kidney transplant that obviated the need for dialysis. The validity of these results has been challenged, but they illustrate the tenuous balance of risk to benefit for patients with diabetes undergoing pancreas transplantation.32 The study is relevant to the possible preference of IIT to WOP because the most important theoretical advantage of IIT over WOP is the reduction in procedure-related mortality and morbidity. Unsurprisingly, our analysis confirmed this advantage of islet transplantation. Our islet transplant patients encountered fewer and less severe complications than those subjected to the major surgery of pancreas transplantation; only one of our islet patients required a blood transfusion and an operation to address an infusion-related complication. In addition, it seems likely that islet infusion–related bleeding complications might be completely avoidable with a different technique. We have recently modified our islet infusion approach from percutaneous infusion by angiography to a mini-laparotomy with operative cannulation of a portal tributary. This should eliminate the possibility of bleeding from a liver puncture site and allow the use of more complete anticoagulation, thereby reducing the risk of portal vein thrombosis. Review of the larger experience at Edmonton indicates that complications of IIT, although unlikely to be life threatening, are not rare and include a 14% rate of transfusion and a 5% rate of branch portal vein thrombosis.27

Reliability and Durability

In our experience and in the recent reports of other experienced islet transplant groups, islet and pancreatic transplantation are similarly likely to render diabetic patients insulin independent, at least temporarily. Only 1 of our 12 patients who completed therapy (9%) failed to come off insulin for at least 2 months.

However, we noted a significant difference when we compared the durability of insulin independence of islet and pancreas transplants, with WOP clearly superior in this regard. Barriers to extended graft function may be most clearly understood by examining long-term success after excluding graft loss caused by technical problems or death in the case of pancreas transplants, and after excluding those instances in which insulin independence never occurred or patients with functioning grafts were withdrawn from the study for islet grafts. Left for consideration in our series were 26 pancreas grafts and 11 islet grafts. Maintenance of insulin independence was better for pancreas grafts within 2 months and became increasingly pronounced over time (P < 0.04). For the 26 WOP grafts, the insulin-free survival rate remained at 100% after 2 years. The 11 islet recipients had an insulin-free survival rate of 100% at 1 month, 91% at 3 months, 80% at 6 months, and 56% at 12 months. When islet graft survival was defined to include those patients requiring only minimal doses of insulin and maintaining C-peptide secretion, islet graft survival more nearly approximated that of pancreas grafts. Attrition of islet graft function was also seen by the Edmonton workers, whose results appear to be the best so far reported,27,28 with 80% of patients insulin independent for 1 year, 70% for 2 years, and 60% for 3 years. Thus, both in our experience and in that of others, islet grafts with established function suffer more late attrition than WOP grafts.

Possible Causes of Late Islet Graft Failure

The attrition of islet graft function over time has not yet been explained, but a number of possibilities exist. These include “exhaustion” of marginally adequate islet mass, development of insulin resistance, the liver as a suboptimal transplant site, toxicity of immunosuppressive agents, rejection, and recurrent autoimmune damage.

That exhaustion of a marginal islet mass might gradually lead to its failure seems quite possible.29 The success of the Edmonton workers in achieving insulin independence is likely best explained by their transplantation of large numbers of islets with the forward-minded strategy of using multiple infusions. We were disappointed to find that our attempts to achieve insulin independence with a single transplant, although initially successful in 5 patients, was eventually followed by recurrent diabetes in 4 of these patients, requiring another transplant for durable success. The Minnesota workers have also recently reported success with single-donor islet allografts, but 2 of 6 such grafts later experienced failure.8

Toxicity of Immunosuppressive Agents

In vitro studies, as well as the frequent post-transplantation development of diabetes by previously normoglycemic recipients of kidney and heart transplants, indicate that commonly used immunosuppressive agents are toxic to pancreatic β-cells. It is also relevant that levels of these orally administered drugs are highest in the portal blood bathing the intrahepatic islets.30 Although the Edmonton workers attributed their success to an immunosuppressive protocol that omitted steroids and minimized levels of calcineurin inhibitors, it seems equally likely that their success was primarily due to the strategy they devised to use serial transplants from multiple donors. Islet graft survival at other centers during the previous decade was quite common and durable (though not potent enough for insulin independence) suggests that standard immunosuppression does not necessarily preclude success.9 Almost all of these islet transplants were performed after or simultaneously with a kidney transplant in patients who therefore received standard immunosuppression, including calcineurin inhibitors and high-dose steroids. These earlier islet transplants did not use multiple donors, which raises the so-far untested possibility that a multiple-transplant strategy accompanied by more vigorous immunosuppression would not only be initially successful, but might also allow for more durable graft survival by preventing immunologic damage to the transplanted islets.

Immune-Mediated Graft Loss

Even retrospectively, a definite diagnosis of rejection is difficult, because obtaining histologic specimens of intrahepatic islets is problematic. However, rejection is a likely explanation of islet graft loss, especially in patients receiving the relatively mild Edmonton immunosuppressive regimen. Because our islet transplant protocol precludes therapy to reverse rejection even if we could diagnose it, islet transplants are presently at a disadvantage to pancreas grafts in this regard.

Autoimmune damage is another possible reason for the late failure of transplanted islets, which are known to be susceptible to recurrent diabetes both in animals and in humans. In fact, the gradual loss of insulin production characteristic of our islet recipients is similar to the gradual loss of the islets in the native pancreas of type I diabetic patients. It is potentially relevant that the immunosuppression regimens for pancreas versus islet transplants differ significantly. Pancreas recipients receive potent polyclonal induction therapy and triple-drug maintenance therapy, which is a regimen of considerably greater magnitude than the protocol for IIT. Thus, it is possible that chronic immune-mediated graft loss, either from rejection or autoimmunity, is more likely to erode the function of islets than whole-organ pancreata. We examined the relative levels of immunosuppressive drugs for those islet patients who lost graft function and for those who did not, and we did not find significant differences. In addition, there were no significant differences evident in transplanted patients in the months before deterioration of graft function compared with a period of stable function (data not shown). However, of interest is our preliminary observation that IAK patients exhibit more robust graft function than ITA patients, as assessed by C-peptide and HgA1c levels (data not shown). This could be attributable to the chronically immunosuppressed pretransplant state of these IAK recipients and perhaps to the use of low-dose steroids.

Several studies in SCID mice indicate that intrahepatic islets may be subject to progressive and unexplained damage.31,32 Our recent observation that islets transplanted to the portal site may also induce local hepatic steatosis in human recipients is another factor to be considered and suggests that the exploration of extrahepatic transplant sites for IIT is a valuable endeavor.33

Resource Utilization

Analysis of resource utilization by pancreas and islet transplantation unexpectedly revealed that attaining insulin independence by IIT was substantially more expensive than by WOP, despite greater hospital length of stay and greater hospital costs associated with the latter. The inclusion of SPK patients in the analysis clearly overestimates the cost of an isolated pancreas transplant. We attempted to compensate for this by specifically examining the costs of our PAK recipients and by eliminating costs directly attributed to the kidney in our SPK recipients. Our adjustment did not affect costs associated with readmission or any specifically clinical data. This is significant in that the SPK group has the most advanced degree of illness, ie, severe renal dysfunction.

Our estimate of islet-related costs is a conservative one because the overhead for maintaining a dedicated islet isolation facility is not included in the cost of processing and is considerable. It should also be noted that we only examined direct costs for these procedures. Indirect costs were not considered and can be substantial for transplant a program. The most important reason for the greater cost of islet transplants was related to the frequent need of multiple pancreata for each recipient. These cost differences were further magnified when we considered costs for organs that were accepted and processed with intent to infuse but were not deemed clinically worthy.

CONCLUSIONS

Much progress has been made over the last decade in the success of human pancreatic IIT. We found our patients as likely to attain temporary insulin independence by IIT as by WOP. However, insulin independence was less likely to be maintained over an extended period of time in our islet recipients than in our pancreas recipients, especially if islets from only one donor were used. If retransplants are performed and success is defined to include patients with maintenance of C-peptide secretion and substantially decreased insulin requirements, then islet and pancreas graft survival are similar. Eventual replacement of pancreas transplants by islet transplantation is suggested by the greater safety of the latter procedure, as confirmed by this report. A major disadvantage of islet transplantation, however, is the requirement of multiple donors for each success and our unexpected finding that it is more expensive than WOP. Until the late attrition we observed in isolated islet graft survival can be prevented by improvement in isolation techniques and/or more effective immunosuppression, we believe that pancreas transplantation and islet transplantation should continue to coexist as complimentary methods.

Discussions

Dr. David E. Sutherland (Minneapolis, Minnesota): I appreciate the opportunity to discuss the paper because, of course, we have a great interest in islet transplantation at the University of Minnesota, and Dr. Barker and his associate, Dr. Markmann, are pioneers in this area. In fact, we began about the same time in the late 1970s at a time when at Minnesota we were looking at the pancreas transplant results of the late Dr. Richard Lillehei and Dr. Najarian—begin the islet program, and we did.

One difference we did with Philadelphia as we progressed, it became obvious to us in the late 1970s that this was going to be a very long-term development, so we actually then went back to pancreas transplantation with requirements in surgical techniques and began our contemporary program. We have now done over 1700 pancreas transplants; there have been over 20,000 done in the world.

But we never abandoned that dream of actually minimally invasive surgery for beta cell replacement. And we have actually promoted the concept, as Dr. Markmann has here, that these should not be competing therapies, they should be complementary, we should just be working toward minimally invasive surgery.

We have done over 100 islet allografts, and in a more recent series of 24, in 20 patients we were able to get 18 off insulin, and achieved that in 16 with a single donor, and 14 still are functioning graft. So we actually have 70% of our 20 patients since the Edmonton series off insulin for single donors.

We have somewhat cheated in that we have used obese donors for individuals that have low insulin requirements. And one of my questions is as to what the insulin requirements were your patients. Because I do agree with you that the Edmonton protocol is not really the immunosuppression but it is the fact that they kept putting islet cells in until they had an adequate bets cell mass and probably any immunosuppression would work.

Nevertheless, it does appear there are differences with your whole pancreas program in regard to immunosuppression, Dr. Markmann, that is one of my questions, is whether that might be responsible for some of your late losses and indeed could it be autoimmunity?

Because in the animal experimental work that you and Dr. Naji and Dr. Barker have done, you have shown that islet transplants may be more susceptible to autoimmune recurrence than whole pancreas grafts, yet you use the non-depleting antibody for induction in your islet transplants while you use the depleting or more potent regimen in your whole pancreas group. Did you do any studies that may shed light on autoimmune recurrence?

I do think that we know that single donors will work. And part of it is because of our experience at Minnesota with islet autografts where even half the pancreas has been subjected to islet isolation, the islet is infused in the face of a total pancreatectomy—Dr. Najarian presented the initial work in 1980 at The American Surgical Association, we updated it in 1995, and we now know that about 75% of individuals that get an adequate islet mass and autograft will remain insulin persistent. So you might want to comment on what some of the differences might be between these 2 groups.

I don't think this is a fair comparison. I don't think one has ever been done, Dr. Markmann, because of using the discarded pancreas for islets. I think that is a criticism of not just you in general but the entire field when we try to make these comparisons.

And indeed if the allocation of the organs was such that with one common list, whether you are getting an islet or a whole pancreas, this is just technical then, it is beta cell replacement, and you could use the good pancreas that is used for the pancreas transplant for your islet autograft recipients, your results might not have been different. You might want to comment on that as well.

Because my own proposal, to UNOs, has been to have a common list and not to make this distinction in allocation. I understand the reasons for it. People are worried about the inefficiency of islets. But it is impeding development of the field. And I don't think there is any doubt that it would develop faster.

And it wouldn't even decrease the number of pancreas transplants. Since there are 6000 deceased donors, there are only 1500 pancreas transplants, at least half should be suitable. And I would advocate that allocation policy and would like your comments on that as well.

The other question I have is something you put in your paper about hypoglycemic unawareness and why does that go away when you actually are still on insulin.

Dr. James F. Markmann (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania): Thank you, Dr. Sutherland, for your comments. Regarding the insulin requirements of our patients, I think we have found exactly what your team in Minnesota has reported in that we do best with a large donor and a small recipient and a recipient who requires a minimal daily dose of insulin. In fact, we have been able to calculate that an average reduction in insulin by one unit requires about 20,000 islets. In this way, we can predict fairly closely the success of the transplantation based on how much insulin the patient requires pretransplant.

I think your point regarding the immunosuppression regimen being used is critical. It is important to realize that these are first-generation trials of islet transplantation and that the Edmonton regimen is unlikely to be the optimal immunosuppression regimen for islets. In fact, we believe that the success reported by Edmonton protocol is more likely attributed to their use of islets from multiple donors than to a magical drug combination. We expect that with application of second and third generation immunosuppression that the results will be even better.

Regarding the post transplant graft dysfunction we observed, it seemed like there were 2 distinct patterns. In the 3 patients who lost complete function, the progression of graft loss appeared typical of an immune mediated process such as rejection or perhaps autoimmunity. We favor rejection in that 2 of the 3 patients who had further monitoring developed antibodies to the donor's HLA antigens indicating that there was some component of an alloimmune response taking place. Three other patients had a slow deterioration of function that required resumption of small doses of insulin and then the function stabilized. In these cases, we doubt immune involvement as we would expect the process to be progressive since no anti-rejection treatment was instituted. Whether these cases are a result of toxicity from high levels of the medications in the portal blood with the islets residing in the liver or whether it is due to chronic autoimmunity is something that remains to be determined.

Regarding the allocation issue, one point that may not be entirely clear from what we have presented is that we seem to have greater difficulty isolating quality islets from a young lean donor than an older obese donor. And while we believe that the younger islets might function better and longer, we are not as successful in their separation. So for the present time we do not find tremendous overlap in what we consider a good islet donor and a good pancreas donor. This allows for the possibility that these 2 techniques can remain complementary and be utilized in parallel for the time being.

Dr. Garth L. Warnock (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada): Dr. Markmann and his colleagues are to be congratulated for advancing our understanding. And I really commend you for bringing our attention to the complementary donation, because we really do need to make full advantage of all the donations that could not otherwise be used for solid organ pancreas transplants. And I think that in the shortage of donor tissue, that is a very key message. I also commend you for the prolonged follow-up in looking at the function of the grafts over time. I have 3 questions for you.

Initially, the attrition of the grafts, despite your providing a very high islet mass, is very accelerated. I wonder if you can speculate, particularly around the donor pancreas. These are a population at risk as donors of type II diabetes, obesity, older age. Could you speculate on whether there are some other factors that you have identified in your donors?

In the immune response, did you look for evidence of anti-islet immunity such as anti-GAD or an autoimmune recurrence as part of the slow attrition in function?

You have switched your protocol to an open mini laparotomy, and I wonder in your experience have you been embolizing the percutaneous tract? And secondly, has there been evidence of portal hypertension when the repeat infusion was done?

Dr. James F. Markmann (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania): Regarding the attrition of the grafts that we have seen, one point that I didn't mention is that we, too, have had success with single-donor infusions, similar to that reported by the Minnesota team. In 5 cases, patients were rendered insulin independent with a single infusion of islets. However, in 4 of those cases, the recipient went on to require either a second islet infusion or were left with minimal graft dysfunction requiring low dose insulin. Two such patients are awaiting a second dose now. This has led us to consider the possibility that a marginal islet mass is what leads to the slow attrition in graft function. It is true, though, that the total islet mass we deliver per patient was quite high (on average, about 15,000 islet equivalents per patient), significantly higher than what was given by the Edmonton team. Thus, why our rate of graft attrition appears to be higher than that seen in the Edmonton series is still unexplained.

Regarding the use of obese donors, we share your concern that we might inadvertently utilize a donor that has occult type II diabetes. Recent studies we have performed in which we intentionally recovered islets from known type II diabetics, suggest that type II islets exhibit significant functional impairment in vitro in response to glucose and in vivo following transplantation to immunodeficient mice. We have now adopted the approach that for any obese donor that represents with even mild hyperglycemia, a hemoglobin Alc is obtained to detect evidence for chronic blood sugar elevations. We have not yet had the opportunity to check for markers of autoimmunity in the recipients. I think is a very important issue and we should look in the future, both for islet auto-antibodies and T-cells reactive to islet antigens.

Regarding the infusion approach, our angiographers have always embolized the catheter tract with a gel foam plug. Despite this practice, we have encountered bleeding in about 10% of cases. It may be the fact that the islets are infused in a solution containing heparin to help prevent portal vein thrombosis that contributes to this problem. The 2 main complications that can occur from the percutaneous transhepatic infusion procedure are bleeding and thrombosis. Following a recent bleeding complication, we modified our technique to a minilaparotomy approach. We believe using the open procedure will help to eliminate both of these concerns as it will allow us to administer more heparin and simultaneously avoid a puncture site in the hepatic parenchyma. We have only done a couple transplants by this approach to date, but we are convinced that it is a better and safer technique.

Dr. Frank Thomas (Birmingham, Alabama): This paper is an objective assessment of the dilemma in islet replacement therapy at present. The intuitive benefits of isolated islet transplants, including a relatively non-invasive, low-morbidity procedure not requiring hospitalization, should lead to extraordinary advantages, including less morbidity and costs, compared to whole organ transplant. The counter-intuitive results seen here invite a careful analysis of the problems with islet transplantation at present.

Isolated islet transplant procedure success is limited and cost ineffective primarily due to 3 factors: early and late loss of islet function due to immune rejection, requirement for retransplantation, and the necessity for chronic life-long non-specific immunosuppression. Our studies in pre-clinical primate models has led us to the conclusion that these factors can all be obviated by tolerance induction.

Our first paper on successful tolerance in primates was presented to this group 20 years ago and we have made considerable progress since. Presently in our group we have 21 incompatible primate kidney and islet transplants surviving beyond 5 years off all immunosuppression. These animals have been shown to have a stable reversal of all abnormal glycemic parameters off all immunosuppression over a 5-year period. The graft survival is approximately 50% at 5 years without chronic immunosuppression, which is superior to the current clinical results with islet transplant using immunosuppression. Prolonged stable islet function with a single islet transplant, no hospitalizations and no chronic immunosuppressive drugs should result in a huge cost reduction over a 5-year period.

My question to Dr. Markmann is, therefore, what plans if any to induce a long-term immune tolerance are being pursued by his group?

I enjoyed this presentation and appreciate the privilege of discussing this important topic.

Dr. James F. Markmann (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania): Thank you, Dr. Thomas, for your comments and questions. I think you have appropriately focused the discussion on where the field needs to go in developing a tolerance regimen. For transplantation to be applicable to the average diabetic, we cannot utilize chronic immunosuppression as the risk will outweigh the benefits to that population. So I think tolerance is an obvious long-term goal.

Our group has been focusing on the use of a combination T-cell and B-cell targeting using a polyclonal T-cell agent along with anti-CD20 to target B-lymphocytes. This is work that Ali Naji has been pioneering for the last couple of years that like your studies with anti-CD3 immunotoxin looks encouraging in the primates. However, until we have these novel approaches available in the clinic, perhaps we should first deal with the more practical issue of insulin independence requiring multiple donors per recipient and the inefficiencies in the process that render many preparations unsuitable for clinical use. These more immediate problems are equally daunting and will greatly impede the more widespread application of islet transplantation.

Dr. Patricia K. Donahoe (Boston, Massachusetts): I would like to compliment you, Dr. Markmann, on a very thoughtful, careful, and arduous study. Just a question for the future—what is the durability of these cells after storage? Also, what are your plans in the future for amplification and for employing stem cell technology?

Dr. James F. Markmann (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania): Regarding storage, there is some very interesting data that has been reported using a new preservation method for the pancreas that relies on an oxygenated perfluorocarbon solution that sustains cellular ATP levels over time until processing can begin. The initial results look very encouraging, especially for marginal glands. We have not resorted to this approach as yet because of the fact that we have a very effective local organ procurement agency and we are generally able to process our pancreas within 6 to 8 hours of donor cross-clamp. However, other centers that need to transport the pancreases from remote sites have found this approach to be very beneficial and to improve the yields of their isolation and the quality of the resulting product.

You also mentioned the possibility of beta cell amplification pre transplant. This is an active area of research examining means to develop islets from stem cells. Our lab has focused on the possibility and that we will be able to increase transplantable islet mass per donor by using ductal cell precursors and manipulating them to form into additional beta cells. The early results are exciting but I suspect that patient application is some time off. I agree that this is the key issue, we need to develop techniques to yield getting more islets from a single pancreas.

Dr. James C. Thompson (Galveston, Texas): Dr. Markmann, you and your colleagues have presented us with a dilemma. Given a patient who comes to you as a proper candidate, how do you approach the risk/benefit ratios of the 2 procedures, that is, how do you and your patient decide whether to proceed with islet transplantation or whole-organ pancreas transplantation?

Dr. James F. Markmann (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania): Thank you, Dr. Thompson, for your incisive question. At the present time, our philosophy is that whole organ pancreas remains the standard of care for a patient who is going to receive a simultaneous kidney transplant at our center. We have not yet attempted a simultaneous islet-kidney transplant. As you know, about 80% of whole organ pancreases are transplanted together with a kidney and this approach has been highly successful. So for these patients, I think the decision is fairly clear and we favor a whole organ graft unless the patient does not qualify because of medical contraindications. In which case, we would consider islets.

For patients who are being evaluated for a pancreas transplant alone, or a pancreas after kidney, the decision is a little less clear. There was a recent database analysis suggesting that the risk-benefit for a patient receiving a pancreas alone or a pancreas after kidney is very tenuous and in fact may not favor whole organ transplantation. In these patients we try to present the data as objectively as possible, and emphasize the fact that the islet procedure is experimental and while we expect it to be safer the long-term results are not yet known. We really try to leave the decision up to the patient as to whether they prefer an approach that is more established but riskier versus a safer but less well proven alternative. Obviously, for patients who are not candidates for whole organ based on medical conditions, we then recommend them for islets.

Footnotes

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation.

Requests: James F. Markmann MD, PhD, Department of Surgery, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, 3400 Spruce Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104. E-mail: James.Markmann@UPHS.upenn.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kelly W, Lillehei R, Merkel F, et al. Allotranspllantation of the pancreas and duodenum along with the kidney in diabetic nephropathy. Surgery. 1967;61:827–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramsay RC, Goetz FC, Sutherland DER, et al. Progression of diabetic retinopathy after pancreas transplantation for insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:208–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bilous RW, Mauer SM, Sutherland DER, et al. The effects of pancreas transplantation on the glomerular structure of renal allografts in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rayhill SC, D'Alessandro AM, Idorico JS, et al. Simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation and living related donor renal transplantation in patients with diabetes: is there a difference in survival? Ann Surg. 2000;231:417–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fioretto P, Steffes MW, Sutherland DER, et al. Reversal of lesions of diabetic nephropathy after pancreas transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Humar A, Kandaswamy R, Granger D, et al. Decreased surgical risks of pancreas transplantation in the modern era. Ann Surg. 2000;231:269–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Venstrom JM, McBride MA, Rother KI, et al. Survival after pancreas transplantation in patients with diabetes and preserved kidney function. JAMA. 2003;290:2817–2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hering BJ, Ricordi C. Islet transplantation for patients with type 1 diabetes. Graft Rev. 1999;2:12–27. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brendel M, Hering B, Schulz A, et al. International islet transplant registry report. Justus-Liebis: University of Giessen; 1999:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gruessner AC, Sutherland DER. Pancreas transplant outcome for United State (US) cases reported to the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) and non-US cases reported to the International Pancreas Transplant Registry (IPTR) as of October, 2000. Clin Transpl. 2000;4:45–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shapiro AMJ, Lakey JRT, Ryan EA, et al. Islet transplantation in 7 patients with type I diabetes mellitus using a glucocorticoid-free immunosuppressive regimen. N Engl J Med 2000;343:230–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Markmann JF, Deng S, Huang X, et al. Insulin independence following isolated islet transplantation and single islet infusions. Ann Surg. 2003;237:741–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hering BJ, Kandaswamy R, Harmon JV, et al. Transplantation of cultured islets from 2-layer preserved pancreases in type 1 diabetes with anti-CD3 antibody. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:390–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shapiro AM, Ricordi C, Hering B. Edmonton's islet success has indeed been replicated elsewhere. Lancet. 2003;361:2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ault A. Edmonton's islet success tough to duplicate elsewhere. Lancet. 2003;362:1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ricordi C, Lacy PE, Scharp DW. Automated islet isolation from human pancreas. Diabetes. 1989;38(suppl 1):140–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linetsky E, Bottino R, Lehmann R, et al. Improved human islet isolation using a new enzyme blend, liberase. Diabetes. 1997;46:1120–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Markmann JF, Deng S, Desai NM, et al. The use of non-heart-beating donors for isolated islet transplantation. Transplantation. 2003;75:1423–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ballinger WF, Lacy PE. Transplantation of intact pancreatic islets in rats. Surgery. 1972;72:175–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reckard CR, Barker CF. Transplantation of isolated pancreatic islets across strong and weak histocompatibility barriers. Transplant Proc. 1973;5:761–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Najarian JS, Sutherland DER, Matas AJ, et al. Human islet transplantation: a preliminary report. Transplant Proc. 1977;9:233–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warnock GL, Kneteman NM, Ryan E, et al. Long term follow-up after transplantation of insulin producing pancreatic islets into patients with type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabelogia. 1992;35:89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tzakias G, Ricordi C, Alejandro R, et al. Pancreatic islet transplantation after upper abdominal exenteration and liver replacement. Lancet. 0000;336:402–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Scharp DW, Lacy PE, Santiago JV, et al. Results of our first nine intraportal islet allografts in type I, insulin-dependent diabetic patients. Transplantation. 1991;51:76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaufman DB, Baker MS, Chen X, et al. Sequential kidney/islet transplantation using prednisone-free immunosuppression. Am J Transplant. 2002;2:674–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bertuzzi F, Grohovaz F, Maffi P, et al. Successful transplantation of human islets in recipients bearing a kidney graft. Diabetologia. 2002;45:77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryan EA, Lakey JR, Paty BW, et al. Successful islet transplantation: continued insulin reserve provides long-term glycemic control. Diabetes. 2002;51:2148–2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryan EA, Lakey JRT, Rajotte RV, et al. Clinical outcomes and insulin secretion after islet transplantation with the Edmonton protocol. Diabetes. 2001;50:710–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davalli AM, Ogawa Y, Ricordi C, et al. A selective decrease in the beta cell mass of human islets transplanted into diabetic nude mice. Transplantation. 1995;59:817–820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Desai NM, Goss JA, Deng S, et al. Elevated portal vein drug levels of sirolimus and tacrolimus in islet transplant recipients: local immunosuppression or islet toxicity? Transplantation. 2003;76:1623–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mattson G, Janson L, Nordin A, et al. Evidence of functional impairment of syngeneically transplanted mouse pancreatic islets retrieved from the liver. Diabetes. 2004;53:948–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hiller WF, Klempnauer J, Luck R, et al. Progressive deterioration of endocrine function after intraportal kidney subcapsular rat islet transplantation. Diabetes. 1991;40:134–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Markmann JF, Rosen M, Siegelman E, et al. MR defined periportal steatosis following intraportal islet transplantation: a functional footprint of islet graft survival? Diabetes. 2003;52:1591–1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]