Abstract

Objective:

Report overall long-term results of stage 0 rectal cancer following neoadjuvant chemoradiation and compare long-term results between operative and nonoperative treatment.

Methods:

Two-hundred sixty-five patients with distal rectal adenocarcinoma considered resectable were treated by neoadjuvant chemoradiation (CRT) with 5-FU, Leucovorin and 5040 cGy. Patients with incomplete clinical response were referred to radical surgical resection. Patients with incomplete clinical response treated by surgery resulting in stage p0 were compared to patients with complete clinical response treated by nonoperative treatment. Statistical analysis was performed using χ2, Student t test and Kaplan-Meier curves.

Results:

Overall and disease-free 10-year survival rates were 97.7% and 84%. In 71 patients (26.8%) complete clinical response was observed following CRT (Observation group). Twenty-two patients (8.3%) showed incomplete clinical response and pT0N0M0 resected specimens (Resection group). There were no differences between patient's demographics and tumor's characteristics between groups. In the Resection group, 9 definitive colostomies and 7 diverting temporary ileostomies were performed. Mean follow-up was 57.3 months in Observation Group and 48 months in Resection Group. There were 3 systemic recurrences in each group and 2 endorectal recurrences in Observation Group. Two patients in the Resection group died of the disease. Five-year overall and disease-free survival rates were 88% and 83%, respectively, in Resection Group and 100% and 92% in Observation Group.

Conclusions:

Stage 0 rectal cancer disease is associated with excellent long-term results irrespective of treatment strategy. Surgical resection may not lead to improved outcome in this situation and may be associated with high rates of temporary or definitive stoma construction and unnecessary morbidity and mortality rates.

Neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy for distal rectal cancer may lead to complete clinical response or complete pathologic response in about 30% of patients. Seventy-one patients with complete clinical response followed by observation alone were compared with 22 patients with complete pathologic response following radical surgery. Radical surgery patients experienced high rates of stoma creation and unnecessary operative morbidity and mortality, without 5-year overall or disease-free survival advantage.

Multimodality approach is the preferred treatment strategy for distal rectal cancer, including radical surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. A significant proportion of patients managed by surgery, performed according to established oncological principles, appear to benefit from chemoradiation (CRT) therapy either pre- or postoperatively in terms of survival and recurrence rates.

Preoperative CRT may be associated with less acute toxicity, greater tumor response/sensitivity, and higher rates of sphincter-saving procedures when compared with postoperative course.1,2 Furthermore, tumor downstaging may lead to complete clinical response (defined as absence of residual primary tumor clinically detectable) or complete pathologic response (defined as absence of viable tumor cells after full pathologic examination of the resected specimen, pT0N0M0). These situations may be observed in 10% to 30% of patients treated by neoadjuvant CRT and may be referred as stage 0 disease.3–8 Surgical resection of the rectum may be associated with significant morbidity and mortality, and in these patients, with significant rates of stoma construction.9 Moreover, surgical resection may not lead to increased overall and disease-free survival in these patients. For this reason, it has been our policy to carefully follow these patients with complete clinical response assessed after 8 weeks of CRT completion by clinical, endoscopic, and radiologic studies without immediate surgery. Patients considered with incomplete clinical response are referred to radical surgery. Surprisingly, up to 7% of these patients may present complete pathologic response (pT0N0M0) without tumor cells during pathologic examination, despite incomplete clinical response characterized by a residual rectal ulcer.8

To determine the benefit of surgical resection in patients with stage 0 rectal cancer treated by preoperative CRT therapy, we compared long-term results of a group of patients with incomplete clinical response followed by radical surgery versus a group of patients with complete clinical response not operated on.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Two-hundred sixty-five patients with adenocarcinoma of the distal rectum (0–7 cm from anal verge) considered resectable, between 1991 and 2002, at the Division of Colorectal Surgery, University of São Paulo Medical School, were referred to preoperative CRT therapy (CRT). CRT regimen consisted of 5040 cGy delivered at the isodose line given at 180 cGy/d for 5 days per week, for 6 consecutive weeks, using a 6-mV to 18-mV linear accelerator. Concurrently, patients received 5-fluoracil (425 mg/m2/d) and folinic acid (20 mg/m2/d) administered intravenously for 3 consecutive days on the first and last 3 days of radiation therapy.3 Patients with synchronous distant metastasis were excluded from this study. Pretreatment staging was determined by clinical, radiologic, and endoscopic studies, including full physical examination, digital rectal examination, proctoscopy, colonoscopy (when possible), chest radiograph, abdominal and pelvic computed tomography, and serum CEA levels. Endorectal ultrasound was performed in selected cases, depending on the institutional equipment availability.

After 8 weeks from completion of CRT, patients were reevaluated by an experienced colorectal surgeon to assess tumor response using the same pretreatment clinical, endoscopic, and radiologic parameters. During proctoscopy, biopsies were obtained for pathologic examination. In selected cases, these biopsies were made in the operating room under anesthesia. At this moment, colonoscopy was performed in patients with initial obstructive tumors, as full endoscopic examination of the remaining large bowel was not possible at initial staging.

The presence of any significant residual ulcer or positive biopsies performed during proctoscopy was considered incomplete clinical response. Patients without any abnormality during tumor response assessment were considered to have complete clinical response.

Patients considered complete clinical responders during tumor response assessment were not immediately operated on. These patients were referred to monthly follow-up visits for repeat physical and digital rectal examination, proctoscopy, biopsies (when feasible), and serum CEA levels. Patients in this group were carefully advised that initial tumor remission could be temporary and, therefore, a strict follow-up adherence was mandatory. Abdominal and pelvic CT scans and chest radiographs were repeated every 6 months during the first year. Patients with sustained complete tumor regression for at least 12 months were considered stage 0 (Observation group OB). During the second and third years after treatment, patients were advised to follow-up visits every 2 months and 6 months, respectively. Patients who developed distant metastasis at any time without recurrence of the primary tumor were treated exclusively for metastatic disease.

Patients with partial or absent response to CRT identified at clinical, endoscopic and radiologic assessment were classified as incomplete clinical responders and were referred to immediate radical surgery. Operation included high inferior mesenteric artery ligation, combined resection of adjacent organs, distal and radial free margins, and total mesorectal excision (TME). Operative procedures performed were abdominal-perineal resection (APR) or low anterior-resection with colorectal or coloanal anastomosis (CAA). Diverting loop ileostomies were performed in patients with coloanal anastomosis.

In both groups, patients did not receive any adjuvant chemotherapy. Adjuvant therapy was considered only in patients with recurrent disease.

Patients with incomplete clinical response treated by radical surgery were staged according to final pathology report and International Union Against Cancer and American Joint Committee on Cancer (UICC/AJCC) recommendations. Pathologic examination was performed by the same experienced pathologist. Patients with pT0N0M0 were considered stage p0 (Resection group R). Follow-up visits were scheduled every 3 months in the first 2 years following operation and every 6 months for subsequent years.

Patients in whom tumor response assessment following CRT was inconclusive were advised to repeat assessment every 4 weeks at the discretion of the colorectal surgeon.

Patients in Resection group R were compared with patients with in Observation group OB in terms of pretreatment staging, initial tumor size (pretreatment), distance from anal verge, post-treatment tumor size, overall survival, disease-free survival, and recurrence. Recurrence was further classified as local (endorectal), pelvic, or systemic (distant metastasis).

Statistical analysis was performed using χ2, Student t test, and Kaplan-Meier curves for survival analysis.

RESULTS

Observation Group

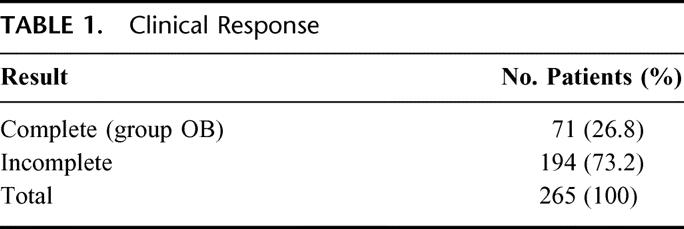

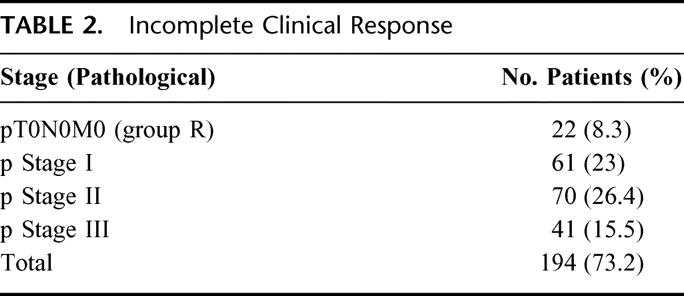

Seventy-one patients had complete clinical response 8 weeks after completion of CRT therapy (26.8%) and were enrolled in the Observation group OB (Table 1). Gender distribution showed 36 male (51%) and 35 female patients. Mean age was 58.1 years, ranging from 35 to 92. Pretreatment mean tumor size was 3.7 cm (1-7 cm), and initial mean distance from anal verge was 3.6 cm (0-7 cm). According to pretreatment clinical and radiologic staging, 14 patients had a T2 lesion (19.7%), 49 patients had T3 lesions (69%), and 8 had T4 lesions (11.3%). Sixteen patients had radiologic evidence of N+ lesions (22.5%) (Table 3).

TABLE 1. Clinical Response

TABLE 3. Pretreatment Clinical Characteristics

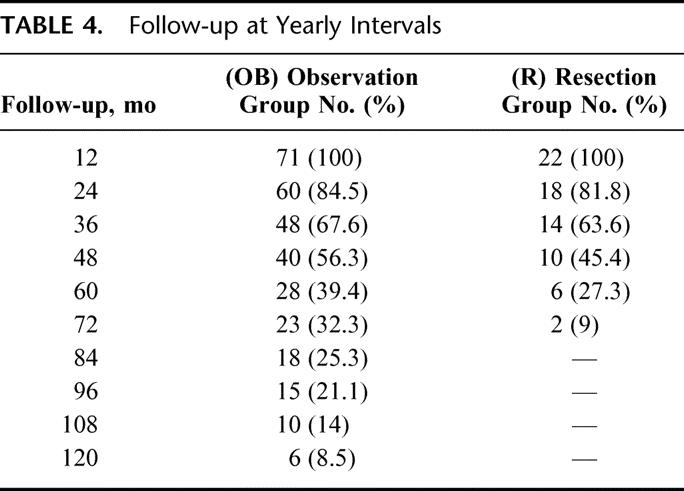

Mean follow-up period was 57.3 months (12-156). Sixty patients (84.5%) had at least 24 months of follow-up. Overall, 57 patients (80%) have been seen and examined within the last 12 months. Follow-up at yearly intervals is indicated in Table 2. Two patients (2.8%) developed endoluminal recurrence after 56 and 64 months of CRT completion. The former was treated by transanal full-thickness excision. Pathologic examination revealed a pT1 and the patient is alive without recurrence, with 72 months of follow-up. The latter was managed by salvage brachytherapy and is alive without recurrence after 132 months of follow-up (over 5 years after brachytherapy). Three patients developed systemic metastases (4.2%) at 18, 48, and 90 months of follow-up. All 3 patients are alive and being treated by systemic chemotherapy. None of the patients developed pelvic recurrence. Overall recurrence rate was 7.0%. There were no cancer-related deaths in the OB group. Five-year overall and disease-free survival rates were 100% and 92%, respectively. Ten-year overall and disease-free survival rates were 100% and 86%, respectively.

TABLE 2. Incomplete Clinical Response

Resection Group

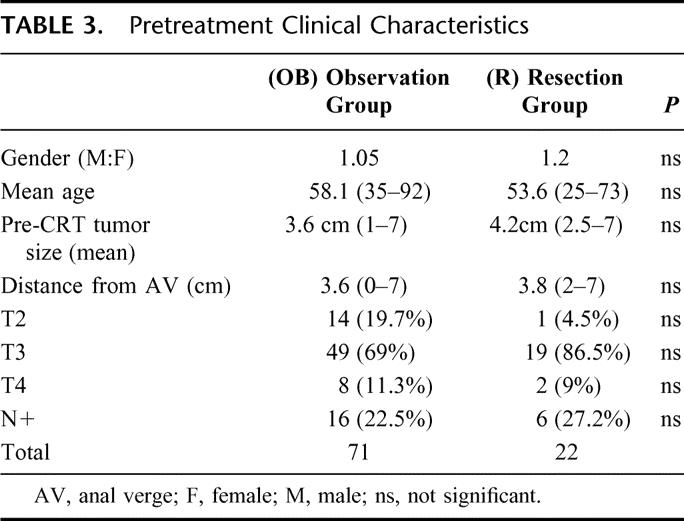

One-hundred ninety-four patients (73.2%) had incomplete clinical response and were treated by radical surgery following CRT completion (Table 2). Twenty-two of these patients (8.3%) showed pT0N0M0 after full pathologic examination of the resected specimens. Gender distribution showed 12 male (54.4%) and 10 female patients. Mean age was 53.6 years, ranging from 25 to 73. Pretreatment mean tumor size was 4.2 cm (2.5–7 cm), and initial mean distance from anal verge was 3.8 cm (2–7 cm). According to pretreatment clinical and radiologic staging, 1 patient had a T2 lesion (4.5%), 19 patients had T3 lesions (86.5%), and 2 had T4 lesions (9%). Six patients had radiologic evidence of N+ lesions (27.2%). Mean follow-up period was 48 months (12–83). Eighteen patients (82%) had a minimum 24 months of follow-up (Table 4). Overall, 16 patients (72%) have been seen and examined within the last 12 months. Follow-up at yearly intervals is indicated in Table 4.

TABLE 4. Follow-up at Yearly Intervals

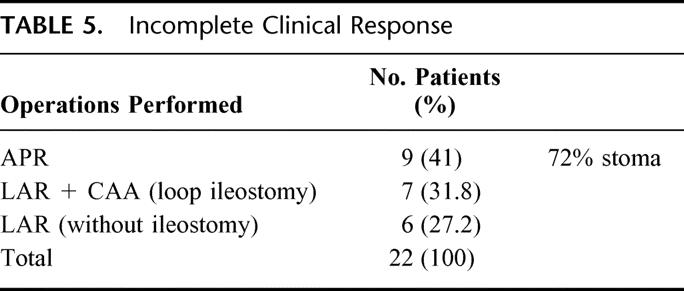

Nine patients were treated by APR (41%) and the remaining 13 patients by sphincter-saving procedures. Of these latter, 7 had diverting loop ileostomies for coloanal anastomosis. Overall, 16 patients had a stoma, either temporary or definitive (72.7%) (Table 5). There was no perioperative mortality or surgery-related significant morbidity requiring reoperation or ICU admission. However, 2 patients developed parastomal hernias requiring reoperation at 12 and 18 months from initial treatment. Mean residual scar size at pathology report was 2.4 cm (1–6 cm), reflecting a significant lesion size reduction (P < 0.001). One patient developed central nervous system unresectable metastases at 19 months of follow-up and died at 21 months after APR. Another patient developed unresectable liver metastases at 21 months of follow-up and died at 24 months after a low anterior resection. One last patient developed multiorgan metastatic disease at 24 months of follow-up after a low anterior resection and is still alive receiving systemic chemotherapy. Overall recurrence rate and cancer-related mortality rate was 13.6% and 9% respectively. None of the patients developed pelvic recurrence. Five-year overall and disease-free survival rates were 88% and 83%, respectively.

TABLE 5. Incomplete Clinical Response

Initial tumor size, gender distribution, age, primary tumor differentiation, and pretreatment clinical stage showed no statistical difference between groups R and OB (Table 4). There was significant reduction in primary tumor size between pretreatment and posttreatment in both groups (P < 0.001).

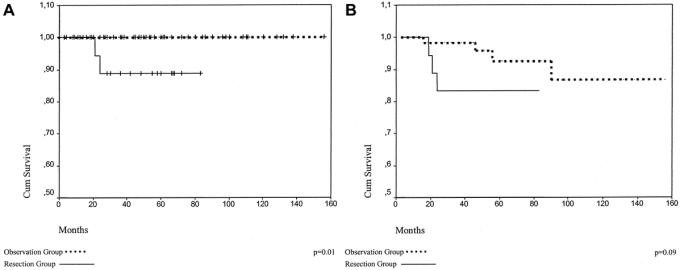

Recurrence and mortality rates showed no statistical difference between groups OB and R (P = 0.2). Since there were no cancer-related deaths in group OB, this group showed slightly but significantly higher 5-year survival rates (P = 0.01) according to Kaplan-Meier curves. Disease-free survival, however showed no significant difference between Kaplan-Meier curves in the same period (P = 0.09; Fig. 1A, B).

FIGURE 1. A, Overall survival. B, Disease-free survival.

Altogether, 93 patients were considered to have stage 0 disease (35%) after CRT therapy (CRT). Six patients developed systemic recurrence not amenable to curative resection (6.4%), and 2 of them died of disease progression (2.2%). Endorectal recurrence occurred in 2 patients (2.8%) treated by nonoperative approach and were successfully managed by salvage transanal surgical resection or brachytherapy. Ten-year overall and disease-free survival rates were 97% and 84%, respectively. Overall, operations were performed in 23 (24.7%), and definite or temporary stomas in 16 patients (72%). There were 4 noncancer-related deaths at 14, 48, 54, and 86 months of follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Multimodality approach has been considered the preferred treatment strategy for distal rectal cancer.3,4,10 Local recurrence is a major concern in rectal cancer management and is associated with poor survival and quality of life and significant morbidity.11–13 Pelvic recurrence rates reported are extremely variable, ranging from 3% to 30%.14–19 Several factors may influence the incidence of local recurrence, such as depth of penetration of the tumor through rectal wall (pT status), presence of lymph node metastasis (pN status), free distal and radial margins, the surgeon's experience, and basic surgical principles.10,20–23

Specifically, TME has been associated with extremely low local recurrence rates in the treatment of rectal cancer.14,15,18 However, surgery alone, even when adequate TME is performed by an experienced colorectal surgeon, failed to reproduce these observations in controlled randomized trials.24 In fact, radical surgery with TME may result in significantly low recurrence rates only in selected patients.25 Thus, adjuvant therapy has an important role in the management of rectal cancer despite TME.11

The use of preoperative CRT therapy may result in significant lower recurrence rates when compared with surgery alone and TME with similar morbidity and mortality rates.24,26 However, the number of patients irradiated may exceed by far the number of who will actually benefit from this treatment strategy. Patients with stage III may have greater reduction in recurrence rates when compared with patients with stage II.24,27

Preoperative CRT may also result in tumor downstaging, leading to significant primary tumor size reduction, depth of penetration, and possibly lymph node sterilization.4,7,28–31 This effect may ultimately result in higher frequency of sphincter-saving operations performed and limit the need for definitive colostomies in the treatment of distal rectal cancer, once considered standard of care for this condition. Furthermore, tumor downstaging may be correlated with better overall and disease-free survival.3,29,30

Moreover, tumor downstaging may be significant enough to determine eradication of all viable tumor cells in the primary rectal tumor and regional lymph nodes. This complete tumor regression may be determined by thorough pathologic examination after radical resection of the rectum. This condition is termed complete pathologic response and is reported to occur in 5% to 30% of patients treated by preoperative CRT.3,5–7,32–34 The variation between these reported results may be associated with the differences in the CRT regimens and specially the interval between CRT and surgery. Possibly, longer periods between CRT and surgery may result in higher rates of complete pathologic response.3,8,35

Ideally, complete pathologic response is warranted for every patient with distal rectal cancer treated by preoperative CRT. Since local recurrence in patients treated by neoadjuvant CRT is associated with the grade of primary tumor response, this subgroup of patients with complete pathologic response may present even lower local recurrence rates. In the present study, none of the 22 patients with pT0N0M0 (Resection group) had evidence of local recurrence after a mean follow-up period of 48 months. Usually, over 80% of local recurrences occur in the first 2 years and over 90% in the first 3 years following surgery.20 Thus it seems highly unexpected that these patients will recur after 4 years of follow-up. However, control of distant recurrence may not be assured by preoperative CRT therapy. A proportion of patients may develop distant metastasis during CRT, even in the presence of complete pathologic response of the primary tumor. Medich et al5 reported 20% of patients initially without metastatic disease and treated by preoperative CRT with stage IV disease at operation (pT0N0M1). Furthermore, metastatic disease may develop after CRT and may reflect the presence of microscopic metastatic cells at initial presentation, undetectable by clinical or radiologic studies. In our study, 3 patients in the Resection group, developed distant metastases at 19, 21, and 24 months of follow-up and are possibly due to radiologic understaging at initial presentation.36

Besides assuring the pathologic confirmation of stage 0 disease, operation may, in theory, offer no advantage over observation alone since there is absolutely no tumor tissue removal. Furthermore, surgery for distal rectal cancer is associated with significant mortality and morbidity rates. These rates appear to be similar in patients treated by surgery alone or with preoperative CRT. Overall surgical morbidity may range from 26% to 45%, including serious complications such anastomotic leaks in approximately 10% of patients.9,37 Also, other possible complications following rectal cancer resection are sexual and urinary dysfunctions, which may occur in approximately 25% of patients treated by radical surgery, even with meticulous nerve-sparing procedures and in highly specialized centers.9,38,39 In turn, mortality rates may reach up to 5% of patients surgically treated for distal rectal cancer.9,37 In our previous report of 87 patients treated by preoperative CRT followed by surgery, perioperative morbidity included perineal wound infection in 25%, urinary complications in 12%, and anastomotic leakage in 2% of patients, while mortality rate was 2%.3 In the present study, there was no operative mortality or significant immediate morbidity. However, 2 patients (10%) from the Resection group R developed late parastomal hernias requiring relocation of original stoma site.

Even though preoperative CRT result in significant tumor downstaging and sphincter-saving procedures, stomas will be performed in the great majority of patients. Considering distal rectal cancer, standard operations include APR with a definitive colostomy or a low-anterior resection with CAA and diverting temporary colostomy or ileostomy. In our study, a stoma (either temporary or definitive) was performed in 16 patients (72%) with pT0N0M0. In many series, a diverting stoma is considered imperative for low CAA, especially following preoperative radiotherapy.40 In this setting, these significant morbidity, mortality, and stoma construction rates may be considered unnecessary in the event of a complete pathologic response.

To avoid unnecessary disadvantages of surgery for stage 0 rectal cancer, clinical assessment of post-CRT staging should be optimized. It may be very difficult to distinguish between residual tumor and actinic ulcers or intramural fibrosis following CRT. In our previous report, initial assessment of primary tumor response from 9 patients was inconclusive. However, residual tumor detection led to immediate salvage resection (3–14 months).3 Presently, in a total of 14 patients (including the previous 8), diagnosis of residual tumor following CRT was extremely difficult. For this reason, this subset of patients was strictly followed and upon recognition of incomplete tumor regression, immediate surgery was performed. Recently, others have reported a poor correlation between clinical and pathologic response, even when the examination is performed by an experienced specialist. Hiotis et al8 have reported surprisingly high rates of missed T2-3 and N+ lesions in patients initially considered as complete clinical response. Histologically, these tumors presented small microscopic foci, frequently seen as deep nests of tumor cells. However, the majority of the patients of this series were operated on within only 6 weeks from CRT, possibly interrupting ongoing tumor necrosis since longer periods may be associated with higher rates of complete pathologic response. Also, approximately 15% of patients with pT0 tumors had lymph node metastases, an occurrence not observed by us in any of the 22 patients and by others.8 Accordingly, even in patients with distant metastases at operation, pT0N1 tumors is not a frequent observation.5 In a parallel with micrometastases in lymph nodes of rectal cancer, the clinical significance, if any, of small microscopic tumor cell nests or clusters is not yet determined.36,41,42

In the present study, 71 patients (26%) had complete clinical response following CRT and were treated by observation alone. None of the patients developed pelvic recurrence, even though 2 patients developed a late (56 and 64 months) endorectal recurrence successfully treated by full-thickness transanal excision (pT1) or brachytherapy. Also, systemic recurrence occurred in similar rates of patients treated by CRT followed by surgery. There was no overall or disease-free survival advantage in Resection group over Observation group with a mean of 54.9 months of follow-up.

In conclusion, CRT may lead to significant rates of complete clinical (stage c0) or pathologic (stage p0) response for distal rectal adenocarcinoma. Stage 0 disease is associated with excellent long-term results irrespective of treatment strategy. Appropriate identification of stage 0 disease after CRT for distal rectal cancer is mandatory to identify a subset of patients that may be safely managed by strict follow-up and observation alone. Surgery may be associated with significant morbidity, mortality, and stoma construction rates, without overall or disease-free survival benefit over observation alone.

Discussions

Dr. Fabrizio Michelassi (Chicago, Illinois): With widespread use of neoadjuvant therapy for rectal cancer, we are frequently faced with patients with complete clinical responses. Due to our inability to select patients with a complete pathologic response, current practice dictates that neoadjuvant therapy be followed by resection therapy. Unfortunately, resection therapy may lead to more than one surgical procedure, to less than perfect functional results or even a permanent stoma. This is a high price to pay for our inability to detect residual microscopic disease. Rejoicing in the news that histopathologic analysis of the specimen reveals no residual tumor goes only that far to balance out the morbidity and potential mortality of what turned out to be unnecessary surgery. Hence the importance of this study.

But how do we identify complete responders? The authors have judged complete response on clinical grounds only. Some groups recommend pre- and post-treatment endorectal ultrasound or MRI to confirm T0 and NO status. This is borne out by the 10–15% incidence of residual neoplastic burden in the face of complete clinical response.

I have several questions for the authors. How were patients selected for neoadjuvant therapy? One in 5 patients had a T2 tumor on pre-treatment evaluation. Patients with T1-2 tumors do not usually receive neoadjuvant therapy because the morbidity associated with the treatment does not justify the modest improvement in local control already achieved with accurate surgical procedure. What preoperative algorithm do the authors currently follow in the presence of a rectal T1-2 tumor?

How long did the authors wait after completion of the neoadjuvant therapy to decide whether to operate or not? The longer you wait, the more complete response you have.

Was any postoperative chemotherapy given to the resected group? Was any post-treatment therapy given to the observation group?

Over all, one in three patients had a complete clinical or pathologic response. Can the authors speculate on the pre-treatment tumor characteristics predictive of a complete response? It would be very useful to be able to predict which tumors respond completely to neoadjuvant therapy.

I do think that there is a group of patients that can be observed after chemoradiation, but the problem I had is identifying them. Before any firm conclusions are reached, I suggest that 2 things occur. First, this cohort of patients is followed for a longer period. We know that neoadjuvant therapy delays local recurrence. The mean follow-up period of 57 months in the observation group may not be sufficient to tell the whole story. After all, during the same observation period only 4% of patients developed systemic disease. Second, this study needs to be reproduced prospectively in an orderly fashion by others.

The results presented today challenge the current surgical principles by which all of us treat our patients and, if reproduced, they would potentially change current practice. I would like to commend Dr. Habr-Gama for her dedication to this treatment option and for stimulating all of us to refine the therapeutic options facing a patient with rectal cancer. Thank you very much for allowing me to discuss this very stimulating paper.

Dr. David A. Rothenberger (Minneapolis, Minnesota): Many of the comments that I had were just covered by Dr. Michelassi, but I would like to add a question for you on whether you have correlative studies in the works to identify tumors that are likely to respond well to neoadjuvant chemoradiation based on molecular markers or other fingerprints of tumor activity?

Secondly, you have chosen an 8-week interval, which I think is not an unreasonable interval, but I wonder if you have specific data to suggest that that is the optimal interval between timing of completion of chemoradiation and the onset of your radical surgery. Thank you for presenting this provocative paper. I hope it stimulates prospective trials.

Dr. Angelita Habr-Gama (Sao Paulo, Brazil): Our University is very honored for this paper being accepted to be presented to this important Society. We thank you very much for this, and also for the privilege of the opportunity for discussion.

We know this paper is very controversial as far as the strategy of treatment is concerned. Our first aim when we started the protocol of preoperative radio/chemotherapy was to reduce the incidence of local recurrence and also to increase the number of sphincter-saving operations. Surprisingly, in some cases, after operation it was found no tumor cells at the resected specimens, and then we changed our ideas. We took this challenge ourselves and concluding that if we had a rectal tumor which had disappeared following neoadjuvant treatment we wouldn't like to have our rectum removed or even to undergo a sphincter-saving operation with a significant risk of anal dysfunction and perioperative morbidity. So, we started to carefully follow the patients after discussing this strategy of treatment with them, explaining that disappearance of tumor could be temporary. We are concerned about the difficulty in recognizing complete tumor regression. In some patients there is no doubt, because when a proctoscope is inserted not even a scar is seen. We are conscious that even in such cases tumor cells may be present, but perhaps they may be quiescent. Even so, we followed the patients considered as having complete response and initial results were good, we are continuing doing this.

Why did we include patients considered having T2 tumors in the study? Yes, we are aware of the potential complications of radiotherapy. But in this protocol, we included only patients with distal rectal cancer with primary indication for abdominal perineal resection. We believe that patients with T2 that require abdominal perineal resections, they may benefit from neoadjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy and have the opportunity to present a complete tumor regression or even a significant downstaging making possible to do a colorectal anastomosis or coloanal anastomosis. Patients with T2 tumor suitable for sphincter-saving operation we do not indicate preoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

The second question, both resection and observation groups did not receive any systemic chemotherapy. We gave them chemotherapy only when there was recurrent disease. Recently, however, we are changing this policy and we are offering systemic therapy after the decision that the response was complete and also for the patients managed by surgery with T0 tumors.

As far as follow-up is concerned, we are sure that we have to wait longer. But in both groups we have nearly 50 months of follow-up, and we know that metastases and local recurrence are most prone to occur during the first 3 years. But even so, we are waiting to be sure about the relevance of this protocol. This is the reason we are keeping these patients in a strict follow-up. When we do not operate on these patients, they are followed carefully. Whenever there is any sign of recurrence a radical operation is indicated. Patients are very conscious about this.

How can we predict the response for chemotherapy? There are some papers in the literature (and we also published one or trying through molecular study to select the patients more prone to respond with complete response to preoperative radio/chemotherapy). In our patients, we found that p53 status may correlate to the grade of tumor regression following chemoradiation.

Finally, we have to improve our criteria of judging complete response not only by means of digital, endoscopic, radiological examinations, but, also by biochemical molecular genetic tests. For the future, what do we expect? Perhaps we expect to have more efficient drugs, which associated to radiotherapy, will lead to a greater number of complete clinical response.

Footnotes

Reprints: Angelita Habr-Gama, Professor Rua Manoel da Nóbrega, 1564 Zip 04001-005 São Paulo, SP-Brazil. E-mail: gamange@uol.com.br.

REFERENCES

- 1.Minsky BD, Cohen AM, Kemeny N, et al. Combined modality therapy of rectal cancer: decreased acute toxicity with the preoperative approach. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:1218–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Busse PM, Ng A, Recht A. Induction therapy for rectal carcinoma. Semin Surg Oncol. 1998;15:120–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Habr-Gama A, de Souza PM, Ribeiro U Jr, et al. Low rectal cancer: impact of radiation and chemotherapy on surgical treatment. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1087–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luna-Perez P, Rodriguez-Ramirez S, Rodriguez-Coria DF, et al. Preoperative chemoradiation therapy and anal sphincter preservation with locally advanced rectal adenocarcinoma. World J Surg. 2001;25:1006–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medich D, McGinty J, Parda D, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy and radical surgery for locally advanced distal rectal adenocarcinoma: pathologic findings and clinical implications. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1123–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grann A, Minsky BD, Cohen AM, et al. Preliminary results of preoperative 5-fluorouracil, low-dose leucovorin, and concurrent radiation therapy for clinically resectable T3 rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:515–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janjan NA, Khoo VS, Abbruzzese J, et al. Tumor downstaging and sphincter preservation with preoperative chemoradiation in locally advanced rectal cancer: the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;44:1027–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hiotis SP, Weber SM, Cohen AM, et al. Assessing the predictive value of clinical complete response to neoadjuvant therapy for rectal cancer: an analysis of 488 patients. J Am Coll Surg 2002;194:131–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luna-Perez P, Rodriguez-Ramirez S, Vega J, et al. Morbidity and mortality following abdominoperineal resection for low rectal adenocarcinoma. Rev Invest Clin. 2001;53:388–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guillem JG, Moore HG, Paty PB, et al. Adequacy of distal resection margin following preoperative combined modality therapy for rectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colquhoun P, Wexner SD, Cohen A. Adjuvant therapy is valuable in the treatment of rectal cancer despite total mesorectal excision. J Surg Oncol. 2003;83:133–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamada K, Ishizawa T, Niwa K, et al. Patterns of pelvic invasion are prognostic in the treatment of locally recurrent rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2001;88:988–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller AR, Cantor SB, Peoples GE, et al. Quality of life and cost effectiveness analysis of therapy for locally recurrent rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2000;43:1695–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heald RJ, Ryall RD. Recurrence and survival after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Lancet. 1986;1:1479–1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kapiteijn E, Kranenbarg EK, Steup WH, et al. Total mesorectal excision (TME) with or without preoperative radiotherapy in the treatment of primary rectal cancer: prospective randomised trial with standard operative and histopathological techniques: Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:410–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Improved survival with preoperative radiotherapy in resectable rectal cancer: Swedish Rectal Cancer Trial. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:980–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher B, Wolmark N, Rockette H, et al. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy for rectal cancer: results from NSABP protocol R-01. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1988;80:21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacFarlane JK, Ryall RD, Heald RJ. Mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Lancet. 1993;341:457–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pahlman L, Glimelius B. Pre- or postoperative radiotherapy in rectal and rectosigmoid carcinoma: report from a randomized multicenter trial. Ann Surg. 1990;211:187–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kraemer M, Wiratkapun S, Seow-Choen F, et al. Stratifying risk factors for follow-up: a comparison of recurrent and nonrecurrent colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:815–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stocchi L, Nelson H, Sargent DJ, et al. Impact of surgical and pathologic variables in rectal cancer: a United States community and cooperative group report. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3895–3902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Porter GA, Soskolne CL, Yakimets WW, et al. Surgeon-related factors and outcome in rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 1998;227:157–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quirke P, Durdey P, Dixon MF, et al. Local recurrence of rectal adenocarcinoma due to inadequate surgical resection: histopathological study of lateral tumour spread and surgical excision. Lancet. 1986;2:996–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kapiteijn E, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:638–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simunovic M, Sexton R, Rempel E, et al. Optimal preoperative assessment and surgery for rectal cancer may greatly limit the need for radiotherapy. Br J Surg. 2003;90:999–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ooi BS, Tjandra JJ, Green MD. Morbidities of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy for resectable rectal cancer: an overview. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:403–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Camma C, Giunta M, Fiorica F, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy for resectable rectal cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2000;284:1008–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wichmann MW, Muller C, Meyer G, et al. Effect of preoperative radiochemotherapy on lymph node retrieval after resection of rectal cancer. Arch Surg. 2002;137:206–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaminsky-Forrett MC, Conroy T, Luporsi E, et al. Prognostic implications of downstaging following preoperative radiation therapy for operable T3-T4 rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;42:935–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bouzourene H, Bosman FT, Seelentag W, et al. Importance of tumor regression assessment in predicting the outcome in patients with locally advanced rectal carcinoma who are treated with preoperative radiotherapy. Cancer. 2002;94:1121–1130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Willett CG, Warland G, Hagan MP, et al. Tumor proliferation in rectal cancer following preoperative irradiation. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1417–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hyams DM, Mamounas EP, Petrelli N, et al. A clinical trial to evaluate the worth of preoperative multimodality therapy in patients with operable carcinoma of the rectum: a progress report of National Surgical Breast and Bowel Project Protocol R-03. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:131–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minsky BD, Coia L, Haller D, et al. Treatment systems guidelines for primary rectal cancer from the 1996 Patterns of Care Study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;41:21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen ET, Mohiuddin M, Brodovsky H, et al. Downstaging of advanced rectal cancer following combined preoperative chemotherapy and high dose radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1994;30:169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moore HG, Gittleman AE, Minsky BD, et al. Rate of pathologic complete response with increased interval between preoperative combined modality therapy and rectal cancer resection. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:279–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finlay IG, McArdle CS. Occult hepatic metastases in colorectal carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1986;73:732–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petrelli NJ, Nagel S, Rodriguez-Bigas M, et al. Morbidity and mortality following abdominoperineal resection for rectal adenocarcinoma. Am Surg. 1993;59:400–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maas CP, Moriya Y, Steup WH, et al. Radical and nerve-preserving surgery for rectal cancer in The Netherlands: a prospective study on morbidity and functional outcome. Br J Surg. 1998;85:92–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nesbakken A, Nygaard K, Bull-Njaa T, et al. Bladder and sexual dysfunction after mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2000;87:206–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guillem JG. Ultra-low anterior resection and coloanal pouch reconstruction for carcinoma of the distal rectum. World J Surg. 1997;21:721–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greenson JK, Isenhart CE, Rice R, et al. Identification of occult micrometastases in pericolic lymph nodes of Duke's B colorectal cancer patients using monoclonal antibodies against cytokeratin and CC49: correlation with long-term survival. Cancer. 1994;73:563–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jeffers MD, O'Dowd GM, Mulcahy H, et al. The prognostic significance of immunohistochemically detected lymph node micrometastases in colorectal carcinoma. J Pathol. 1994;172:183–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]