Abstract

Objective:

To investigate the association between gastric surgery and cancer of the larynx.

Summary Background Data:

Biliary reflux is frequent after gastric surgery and may reach the proximal segment of the esophagus and the larynx. It is possible that duodenal content (consisting in bile acids, trypsin), together with pepsin and acid residues when gastric resection is partial, may cause harmful action on the multistratified epithelium of the larynx.

Methods:

A retrospective case-control study on subjects admitted between January 1987 and May 2002 in the same hospital in Rome was carried out. The study included 828 consecutive patients with laryngeal cancer (cases) and 825 controls with acute myocardial infarction. Controls were randomly sampled out of a total of 10,000 and matched with cases for age, sex, and year of admission. Logistic regression models were used to assess the role of gastric resection in determining laryngeal cancer risk while controlling for potential confounding factors.

Results:

Previous gastrectomy was reported by 8.1% of cases and 1.8% of the controls (P < 0.0001). A 4-fold association emerged between gastric surgery and laryngeal cancer risk (adjusted OR = 4.3, 95% CI: 2.4–7.9). The risk appeared strongly increased 20 years after surgery (OR = 14.8, 95% CI: 3.4–64.6). Heavy alcohol drinking (OR = 2.5, 95% CI: 1.8–3.5), smoking (OR = 4.7, 95% CI: 3.3–6.7), and blue-collar occupation (OR = 4.6, 95% CI: 3.2–6.7) were all independently associated with the risk of laryngeal cancer.

Conclusions:

Previous gastric surgery is associated with an increased risk of laryngeal cancer. A periodic laryngeal examination should be considered in long-term follow-up of patients with gastric resection.

Reflux of intestinal contents (biliary reflux) is frequent after gastric resection and may possibly reach the proximal segment of the esophagus and then the larynx. This case–control study reports a significant association between previous gastrectomy and laryngeal cancer. A periodic laryngeal examination should be considered in long-term follow-up of patients with gastric surgery.

Esophageal biliary reflux consists of the regurgitation of intestinal material through the pylorus into the stomach, with consequent reflux into the esophagus. This event may occur after partial (duodenogastroesophageal reflux) or total (duodenoesophageal reflux) resection of the stomach.1–4 In the majority of cases, in addition to the epithelium of the remaining stomach, the most vulnerable tissue is the epithelium of the distal esophagus.5–8 However, it is possible that the reflux may reach the proximal segment of the esophagus and then the larynx, also. There are many reports of laryngeal damage caused by gastroesophageal acid reflux,9–12 whereas there are no data about the effect of biliary reflux on the larynx. A series of reasons suggest a possible harmful action of intestinal contents (bile acids, trypsin), together with pepsin and acid residues when gastric resection is partial, on the multistratified epithelium of the larynx.13–25 It should also be pointed out that these regions have practically no defense mechanisms, unlike the esophagus (where, for example, peristalsis takes place).

Our hypothesis was that biliary reflux after gastric resection may enhance the development of laryngeal malignancies. To investigate this hypothesis, we decided to study the association between a personal history of gastric surgery for a benign condition and cancer of the larynx. We therefore performed a retrospective case–control study, including all patients with laryngeal cancer (LC) who were consecutively admitted to the Otorhinolaryngological Clinical Department of our University Hospital in the period January 1987 to May 2002. To select a control group similar for age and sex and, possibly, smoking history,26 we randomly selected age- and sex-frequency-matched patients with acute myocardial infarction, consecutively admitted to the Cardiac Care Unit of our hospital during the same time period.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We enrolled a total of 828 patients who were admitted to the Otorhinolaryngological Clinical Department of our University Hospital because of a diagnosis of LC. This group included all the patients consecutively admitted between January 1987 and May 2002. Previous surgery for gastric cancer was a criterion for exclusion from the study, but we found no patient previously operated for gastric cancer. The University Hospital database includes an updated medical history with information on risk factors and living conditions, obtained through a structured questionnaire. Data were therefore obtained regarding the time of onset of the laryngeal tumor, place of residence, occupation (classified as white-collar, blue-collar, or other; the latter included housewives, farmers, retired and undefined subjects), smoking history, alcohol consumption, and details of previous surgical interventions.

We randomly selected as control group 828 patients admitted to the Cardiac Care Unit of our hospital (out of a total of 10,000), during the same time period (from January 1987 to May 2002), because of acute coronary events. Patients with a previous history of heart disease (including myocardial infarction, angina, cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, or congenital heart disease) were not considered eligible. A previous history of squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx was identified for 3 controls, and these were excluded from the study. Control subjects were frequency matched with LC cases for age, sex, and year of admission. Again, all data regarding previous medical history and living habits and conditions were obtained from the hospital database.

Our study therefore included a total of 828 cases (761 males and 67 females) and 825 control subjects (758 males and 67 females).

Quality and completeness of the data obtained by the hospital database were confirmed by a direct interview of 115 cases and 115 controls, randomly chosen among the surviving subjects. In particular, data regarding smoking and alcohol history, previous gastrectomy, and living conditions were in agreement with those recorded in the database.

As regards tobacco use, patients were classified as: never smokers (no history of cigarette smoking), former smokers (persons who had smoked but had quit before admission to the hospital), and current smokers (persons who were smoking at the time of the admission). Former and current smokers were also combined in a single category, as “ever smokers,” for comparisons with never smokers. Information about the quit date, number of cigarettes smoked per day, and duration of smoking over time was recorded. Alcohol intake was recorded as the mean number of standard drinks consumed per day (1 standard drink = 12 g of absolute alcohol).27 Patients were subdivided into 3 groups: nondrinkers, including subjects who were teetotalers or who only occasionally drank some alcohol; social drinkers: men or women who reported less than 3 drinks per day or less than 2 drinks per day, respectively; heavy drinkers: men who reported 3 or more than 3 drinks per day; and women who reported 2 or more than 2 drinks per day.28

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD, and comparisons between groups were performed with the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Comparisons of categorical variables were performed with Pearson's χ2 test; a P value < 0.05 (2-tailed) was considered significant. Logistic regression models were used to assess the effect of gastric resection in developing LC while controlling for potential confounding factors. Adjustment variables included in the analysis were: age, sex, geographic area of residence, smoking habits, drinking habits, and occupation. All results from logistic models are expressed as Odds Ratio. 95% CI are given. Analyses were performed with SAS for Windows software.

RESULTS

Study Population

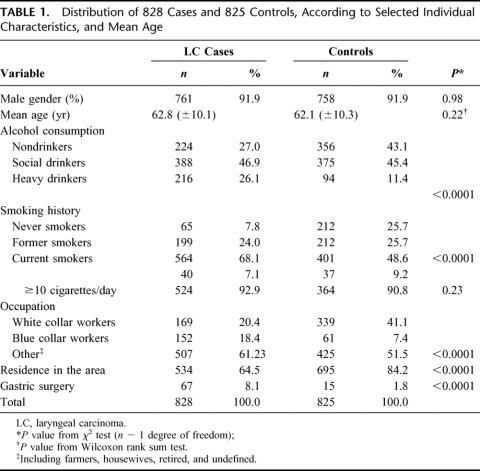

LC cases showed the following laryngeal localization of the tumor: glottic (n = 382, 46.1%), supraglottic (n = 214, 25.8%), transglottic (or multiregional) (n = 212, 25.6%), glottic–subglottic (n = 18, 2.2%), and subglottic (n = 2, 0.3%). Eight hundred eleven (98%) patients had a squamous cell carcinoma and 17 (2%) had a verrucous carcinoma. Individual characteristics of patients and controls are shown in Table 1. The 2 groups were sex- and age-frequency matched, but a low social class was more frequent among cases (white-collar workers were 41% among controls and 20% among cases). Prevalence of smoking and alcohol consumption was also significantly higher in cases than in controls (92.2% versus 74.3% for ever-smoking, P < 0.0001; current alcohol use was 73% versus 56.9%, P < 0.0001). Control subjects were admitted for an acute condition (acute myocardial infarction), and more often (84.2%) lived in the geographical area surrounding our hospital (Lazio, Central Italy) than cases did (64.5%).

TABLE 1. Distribution of 828 Cases and 825 Controls, According to Selected Individual Characteristics, and Mean Age

Gastric Surgery and Cancer of the Larynx

A previous gastric resection was reported by 67 LC cases (8.1%) (97% males; mean age 65.3 ± 9.7 years) and by 15 controls (1.8%) (100% males; mean age 63.1 ± 9.9 years): the difference was significant (P < 0.0001).

Among the 67 LC cases with gastric resection (mean age at surgery = 43.0 ± 13.3 years), 42 (62.7%) had a Billroth-II and 25 (37.3%) a Billroth-I resection; 48 (71.6%) were drinkers (40.3% were social and 31.3% heavy drinkers), 61 (91%) had a smoking history (77.6% were current, 13.4% former and 9% never smokers), and 48 (71.6%) had residence in the area (Lazio, Central Italy). All 67 individuals underwent gastric surgery because of peptic ulcer (64 [95.5%] because of a duodenal ulcer and 3 [4.5%] for a gastric ulcer). The distribution according to specific sites and histologic types of laryngeal cancer among these 67 LC cases was as follows: glottic (n = 34, 50.7%), supraglottic (n = 19, 28.2%), transglottic (or multiregional) (n = 12, 17.8%), glottic–subglottic (n = 2, 2.9%); 66 (98.5%) patients had a squamous cell carcinoma and 1 (1.5%) had a verrucous carcinoma. No difference emerged in comparison to the whole series.

Among the 15 control subjects with gastric resection (mean age at surgery = 47.2 ± 11.5 years), 9 (60%) had a Billroth-II and 6 (40%) a Billroth-I resection; 9 (60%) were drinkers (26.7% were social and 33.3% heavy drinkers), 11 (73.3%) were resident in the area (Lazio, Central Italy) and all of 15 (100%) had a smoking history (73.3% were current and 26.7% former smokers), All these 15 individuals underwent gastric surgery because of peptic ulcer (14 [93.3%] because of a duodenal ulcer and 1 [6.6%] for a gastric ulcer).

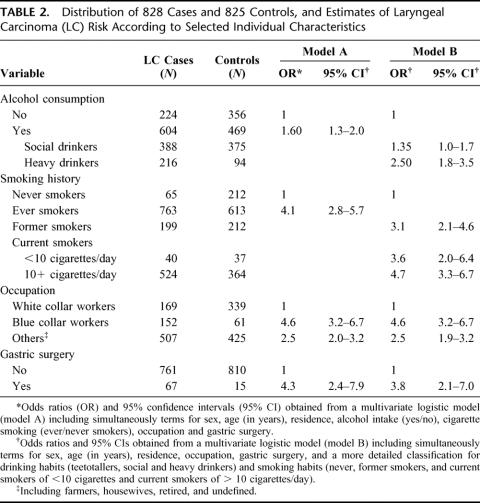

A baseline logistic model (Model A, Table 2) included terms for sex, age, area of residence, alcohol consumption (yes/no), smoking (ever/never), occupation (white-, blue-collar, and other) and gastric surgery. This multivariate analysis showed that blue-collar workers (OR = 4.6, 95% CI = 3.2–6.7), alcohol drinkers (OR = 1.6, 95% CI = 1.3–2.0), and ever-smokers (OR = 4.1, 95% CI = 2.8–5.7) were at significantly increased risk of laryngeal cancer. Previous surgery of the stomach was also significantly associated with laryngeal cancer (OR = 4.3, 95% CI = 2.4–7.9).

TABLE 2. Distribution of 828 Cases and 825 Controls, and Estimates of Laryngeal Carcinoma (LC) Risk According to Selected Individual Characteristics

A multivariate analysis including terms for the same set of confounders but with a more detailed classification of alcohol drinking and smoking (Model B, Table 2) confirmed the significant association between previous gastric resection and cancer of the larynx with an OR of 3.8 (95% CI = 2.1–7.0). Heavy alcohol drinkers (OR = 2.5, 95% CI = 1.8–3.5), current smokers (OR = 4.7, 95% CI = 3.3–6.7), and blue-collar workers (OR = 4.6, 95% CI = 3.2–6.7) were shown to be at significantly increased LC risk in the same multivariate analysis.

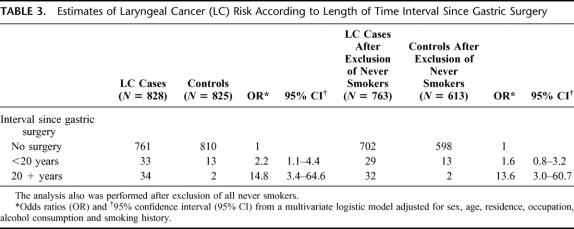

Among LC cases, gastric resection occurred on average 22.3 ± 11.4 years before admission for laryngeal cancer. The association between gastric surgery and laryngeal cancer risk varied according to the time interval and appeared much stronger 20 years after gastric resection: a multivariate analysis showed a risk estimate of 2.2 (95% CI: 1.1–4.4) in the first 20 years after surgery, and 14.8 (95% CI: 3.4–64.6) 20 years after surgery (Table 3).

TABLE 3. Estimates of Laryngeal Cancer (LC) Risk According to Length of Time Interval Since Gastric Surgery

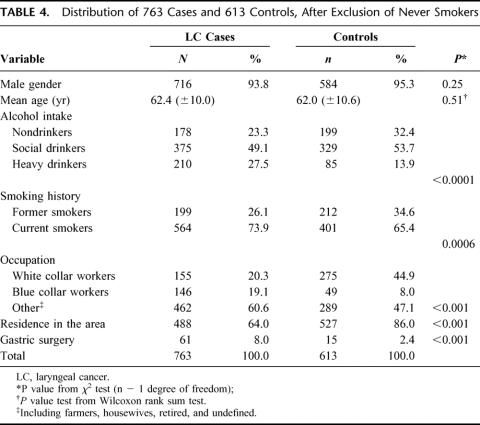

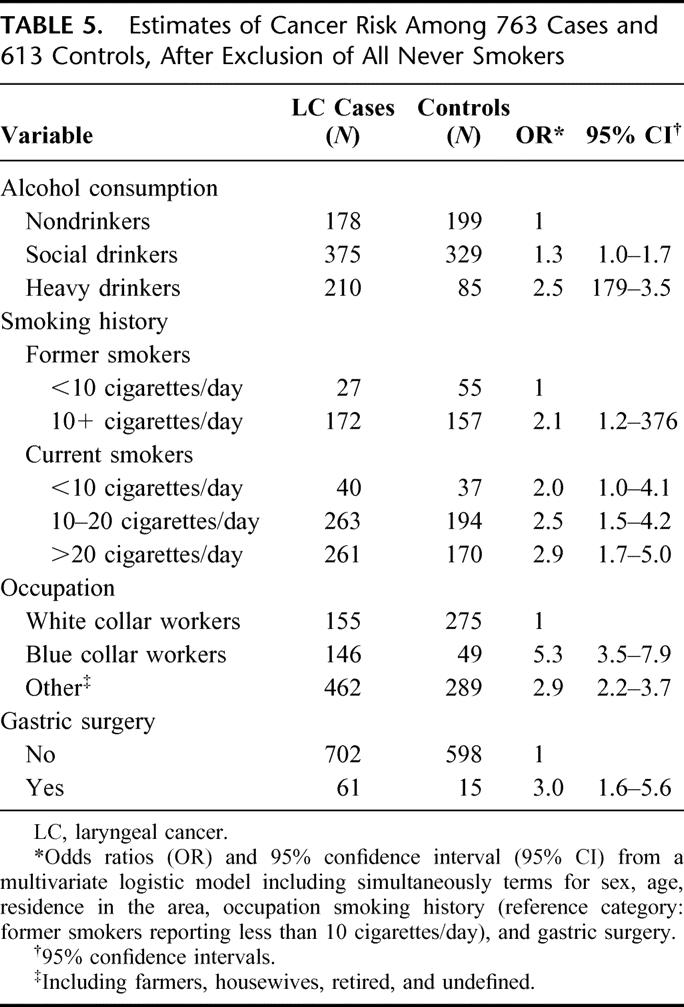

Analyses were repeated in the subgroup of 763 LC cases and 613 controls who were either former or current smokers at interview. Characteristics of cases and controls, after exclusion of never smokers, are shown in Table 4. In this large subgroup, odds ratios obtained from a multivariate logistic models (Table 5), including simultaneously terms for age (in years) and all the variables considered in the previous analyses, confirmed the significant association between previous surgery of the stomach and cancer of the larynx, although somehow weakened (OR = 3.0; 95% CI = 1.6–5.6). This association also appeared to be strongly time-dependent: a multivariate analysis showed a trend of increasing risk over time. The OR was 1.6 (95% CI: 0.8–3.2) for less than 20 years after the date of gastric surgery, and 13.6 (95% CI: 3.0–60.7) for more than 20 years after surgery (Table 3).

TABLE 4. Distribution of 763 Cases and 613 Controls, After Exclusion of Never Smokers

TABLE 5. Estimates of Cancer Risk Among 763 Cases and 613 Controls, After Exclusion of All Never Smokers

DISCUSSION

Our results show that previous gastric surgery is associated with an increased risk of LC. Among subjects who had previously undergone surgery of the stomach for a benign condition such as peptic ulcer, the risk to develop a LC was increased 4-fold in a multivariate analysis, taking into account other strong risk factors such as smoking and alcohol consumption.29–31 A 3-fold risk persisted when the analyses were restricted to ever smokers.

The present study confirms and strengthens the results obtained from our group's recent pilot study, where the development of laryngeal malignancy or premalignancies was found, at long-term follow-up, in 7.5% of previously gastro-resected subjects.32

Our findings support the hypothesis that a chronic reflux of intestinal contents (including bile acids and salts, and pancreatic enzymes), which is often present after gastric resection, together with pepsin and acid residues when gastric resection is partial, may promote the development of laryngeal malignant changes, by creating chronic stimulation and inflammation on the squamous epithelium of the larynx.33 The distance of the larynx from the stomach and the presence of a low-grade, chronic stimulation could explain the long time needed by this reflux to become dangerous. We have shown that the risk increased more than 10-fold 20 years or more after gastric resection.

Obviously, a prerequisite for any complications of reflux is that it occurs to an extent beyond the tolerance of the epithelium. Smoking and alcohol abuse may both decrease this tolerance, as well as also being associated with a higher incidence of reflux disease.34,35 A chronic insult on the laryngeal epithelium, represented by biliary reflux after gastric surgery, may therefore represent (as already demonstrated for acid reflux)9–12 a further risk factor or cofactor for the onset of laryngeal carcinogenesis. Furthermore, gastrectomy also increases the systemic toxicity of ethanol by abolishing the first-pass metabolism and increasing its bioavailability.36

Biliary reflux may be therefore dangerous for the larynx because of several mechanisms. In particular, trypsin can play a role, because when not made inactive by pepsin it remains in action for 1 hour at various pH levels.14 Because of its proteolytic properties, this enzyme may promote the detachment of the surface cells from the epithelium by digesting the intercellular substances and surface structures that contribute to the maintenance of cohesion between the cells.15–17 Bile acids have also been thought to damage mucosal cells by their detergent property and solubilization of the mucosal lipid membranes.18 Because of their lipophilic state, bile acids may also penetrate through the mucosa and cause intramucosal damage by disorganizing membrane structure or interfering with cellular function.18,19 Furthermore, it has been demonstrated in animal models that unconjugated bile acids are able to augment the damaging effects of trypsin at pH 7.20,21

In the present series, 62.7% of LC cases reporting gastric surgery had had a Billroth II reconstruction (subtotal excision of the stomach with gastrojejunal anastomosis and duodenal closure), and 37.3% a Billroth I (subtotal excision of the stomach with gastroduodenal anastomosis). Although the statistical analysis is not possible because of the small size of the sample series, the finding is consistent with the evidence reporting higher levels of biliary reflux in gastric resection with Billroth II reconstruction versus other type of surgical approach (Billroth I and Roux en Y reconstruction).22 Interestingly, higher mean pH values and N-nitrous compound concentrations have been found in patients with Billroth II resection as compared with both Billroth I surgery and normal controls,23 whereas N-nitrous compound levels were also recorded in patients with more severe histologic changes in gastric stump carcinogenesis.24 Higher levels of polyamines (actively involved in cell proliferation) were also observed after Billroth II gastric resection compared with subjects never operated on.25

A limitation of this study is the lack of direct evidence of reflux in our patients. There are many clinical studies showing presence of biliary reflux after gastric resection,1,2 and its evidence would have given further support to our data. Moreover, although biliary reflux may more appropriately be demonstrated by 24-hour esophageal bilirubin monitoring (Bilitec), we previously reported abnormal alkaline reflux in esophagus, by using the 24-hour pH-metry, in 3 patients with both laryngeal cancer and a Billroth II reconstruction after gastric resection.37

Another possible criticism may be because of the possible association between smoking and gastric resection.38,39 Heavy smoking (a strong risk factor for cancer of the larynx) can be related to complications of peptic ulcer disease leading to gastric resection, in particular for patients undergoing surgery before the 1970 to 1980s, when H2-receptor antagonists, proton-pump inhibitors, and Helicobacter pylori eradication had not yet been introduced.40 For this reason, we chose a group of patients with acute myocardial infarction as controls, who were supposed to have a higher prevalence of smoking compared with the normal population.26 Our results also persisted in the analysis performed only in the large subgroup of ever smokers.

On the other hand, we defined smoking status according to patients’ self-reported information. In the context of the University specialist setting, where patients and controls were followed closely and clinical attention was directed toward identifying and minimizing modifiable potential risk factors, smoking status was, therefore, prospectively and systematically assessed. Furthermore, the completeness and the accuracy of the data recorded were directly confirmed by follow-up interviews in a large subgroup in both cases and controls.

Nevertheless, although self-reports seem to be reasonably accurate,41 we cannot exclude the possibility of confounding by income level. In particular, control subjects, who were of higher social status, might be more compliant than cases in reporting their habits. However, adjustment for type of occupation (such as white or blue collar) did not alter the associations found.

Furthermore, although smoking and alcohol intake remain the 2 major risk factors actually recognized to cause laryngeal cancer, there are substances thought to be carcinogens, cocarcinogens, or promotive factors for cancer, such as asbestos, wood dust, coal products, cement sulfuric, acid paints, and acid vapor.42 It is very difficult to prove that a patient has developed LC because of these factors or to separate out their effects from those induced from smoking or alcohol intake. However, the above factors are all included in the extensive category of environmental and occupational risk factors, and, as mentioned earlier, adjustment for occupation did not alter the associations found in the present study.

This study has also several strengths. Our findings show a clear association between laryngeal cancer and previous gastrectomy for the first time. Although the number of gastric resections has been significantly reduced in the last 2 decades, because of better treatment of peptic ulcer disease,43,44 a substantial proportion of the population around retirement age has previously been subjected to gastric surgery because of peptic ulcer. Furthermore, the prevalence of gastric surgeries is also significant among patients with gastric cancer.45,46 Thus, the long-term outcome of these patients is of continuing relevance, and an increased risk for cancer of the larynx for this cohort may still currently be of considerable public health importance. Although further studies should confirm our findings, in particular with assessment of the presence and quality of reflux compounds, we believe that a periodic laryngeal examination should be considered in long-term follow-up of patients with gastric surgery.

Footnotes

Reprints: G. Cammarota, Policlinico Universitario “A. Gemelli,” Istituto di Medicina Interna, Largo A. Gemelli, 8, 00168 Rome, Italy. E-mail: gcammarota@rm.unicatt.it.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mason RJ, DeMeester TR. Importance of duodenogastric reflux in the surgical outpatient practice. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:48–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stoker DL, Williams JG. Alkaline reflux oesophagitis. Gut. 1991;32:1090–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papazian A, Minaire Y, Lambert R, et al. Esophageal bile reflux after gastric surgery. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1981;67(suppl):177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Endo A, Okamura S, Kono N, et al. Esophageal reflux after gastrectomy: a hazard after Billroth-I subtotal gastrectomy. Int Surg. 1978;63:52–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tersmette AC, Giardiello FM, Tytgat GN, et al. Carcinogenesis after remote peptic ulcer surgery: the long-term prognosis of partial gastrectomy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;212:96–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richter JE. Importance of bile reflux in Barrett's esophagus. Dig Dis 2000–2001;18:208–216. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Miwa K, Hattori T, Miyazaki I. Duodenogastric reflux and foregut carcinogenesis. Cancer. 1995;75(suppl):1426–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato T, Miwa K, Sahara H, et al. The sequential model of Barrett's esophagus and adenocarcinoma induced by duodeno-esophageal reflux without exogenous carcinogens. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freije JE, Beatty TW, Campbell BH, et al. Carcinoma of the larynx in patients with gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Otolaryngol. 1996;17:386–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahrilas PJ. Supraesophageal complications of reflux disease and hiatal hernia. Am J Med 2001;111(suppl 8A):51S–55S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olson NR. Aerodigestive malignancy and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Med 1997;103(suppl 5A):97S–99S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koufman JA. The otolaryngologic manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): a clinical investigation of 225 patients using ambulatory 25-hour pH monitoring and an experimental investigation of the role of acid and pepsin in the development of laryngeal injury. Laryngoscope. 1991;101(suppl 53):1–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma ZF, Wang ZY, Zhang JR, et al. Carcinogenic potential of duodenal reflux juice from patients with long-standing postgastrectomy. World J Gastroentrol. 2001;7:376–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imada T, Chen C, Hattori S, et al. Effect of trypsin inhibitor on reflux esophagitis after total gastrectomy in rats. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:1045–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salo JA, Kivilaakso E. Contribution of trypsin and cholate to the pathogenesis of experimental alkaline reflux esophagitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1984;19:875–881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lillemoe KD, Johnson LF, Harmon JW. Alkaline esophagitis: a comparison of the ability of components of gastroduodenal contents to injure the rabbit esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1983;85:621–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mud HJ, Kranendonk SE, Obertop H, et al. Active trypsin and reflux oesophagitis: an experimental study in rats. Br J Surg. 1982;69:269–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schweitzer EJ, Bass BL, Batzri S, et al. Lipid solubilization during bile salt-induced esophageal mucosal barrier disruption in the rabbit. J Lab Clin Med. 1987;110:172–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kivilaakso E, Fromm D, Silen W. Effect of bile salts and related compounds on esophageal mucosa. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1981;67:119–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Champion G, Richter JE, Vaezi MF, et al. Duodeno-gastroesophageal reflux: relationship to pH and importance in Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:747–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nehra D, Howell P, Williams CP, et al. Toxic bile acids in gastroesophageal reflux disease: influence of gastric acidity. Gut. 1999;44:598–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kronert T, Kahler G, Adam G, et al. Fiber optic measurements with the Bilitec probe for quantifying bile reflux after aboral stomach resection. Zentralbl Chir. 1998;123:239–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reed PI, Smith PL, Summers K, et al. The influence of enterogastric reflux on gastric juice bacterial growth, nitrite, and N-nitroso compound concentrations following gastric surgery. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1984;92(suppl):232–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guadagni S, Walters CL, Smith PL, et al. N-nitroso compounds in the gastric juice of normal controls, patients with partial gastrectomies, and gastric cancer patients. J Surg Oncol. 1996;63:226–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorusso D, Linsalata M, Pezzolla F, et al. Duodenogastric reflux and gastric mucosa polyamines in the non-operated stomach and in the gastric remnant after Billroth II gastric resection. A role in gastric carcinogenesis? Anticancer Res. 2000;20:2197–2201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prescott E, Hippe M, Schnohr P, et al. Smoking and risk of myocardial infarction in women and men: longitudinal population study. Br Med J. 1998;316:1043–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Secretary of Health and Human Services. Effects of alcohol on fetal and postnatal development. In: Ninth Special Report to the U. S. Congress on Alcohol and Health (NIH publication 97–4017). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office;1997:193–246. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: a technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption. In: Allen J, Litten RZ, eds. Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychological and Biological Methods. New Jersey: Humana Press;1992:41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shapiro JA, Jacobs EJ, Thun MJ. Cigar smoking in men and risk of death from tobacco-related cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:333–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szyfter K, Szmeja Z, Szyfter W, et al. Molecular and cellular alterations in tobacco smoke-associated larynx cancer. Mutat Res. 1999;445:259–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tuyns AJ. Alcohol and cancer. Pathol Biol. 2001;49:759–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cianci R, Galli J, Agostino S, et al. Long-term gastric resection as risk factor for malignant lesions of larynx. Arch Surg. 2003;138:751–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glanz H, Kleinsasser O. Chronic laryngitis and carcinoma. Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1976;212:57–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dennish GW, Castell DO. Inibitory effect of smoking on the lower esophageal sphincter. N Engl J Med. 1971;284:1136–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vitale GC, Cheadle WG, Patel B. The effect of alcohol on nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux. JAMA. 1987;258:2077–2079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caballeria J, Frezza M, Hernandez-Munoz R, et al. Gastric origin of the first-pass metabolism of ethanol in humans: effect of gastrectomy. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:1205–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cianci R, Fedeli G, Cammarota G, et al. Is the alkaline reflux a risk factor for laryngeal lesions? Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma L, Chow JY, Cho CH. Effects of cigarettes smoking on gastric ulcer formation and healing: possible mechanisms of action. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;27(suppl 1):S80–S86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fielding JE. Smoking: health effects and control. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:491–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parasher G, Eastwood GL. Smoking and peptic ulcer in the Helicobacter pylori era. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000;12:843–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patrick DL, Cheadle A, Thompson DC, et al. The validity of self-reported smoking: a review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1086–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Molony N, Rinaldo A, Marau AGD, et al. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of laryngeal cancer. In: Ferlito A, ed. Diseases of larynx. London: Arnold; 2000:483–492. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schoenfeld PS. Acid peptic diseases in the era of Helicobacter pylori. Lippincotts Prim Care Pract. 1998;2:358–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stabile BE. Redefining the role of surgery for perforated duodenal ulcer in the Helicobacter pylori era. Ann Surg. 2000;231:159–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barchielli A, Amorosi A, Balzi D, et al. Long-term prognosis of gastric cancer in a European country: a population-based study in Florence (Italy). 10-year survival of cases diagnosed in 1985–1987. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:1674–1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Samson PS, Escovidal LA, Yrastorza SG, et al. Re-study of gastric cancer: analysis of outcome. World J Surg. 2002;26:428–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]