Abstract

Objective:

To compare the diagnostic value of contrast-enhanced CT (ceCT) and 2-[18-F]-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose-PET/CT in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer to the liver.

Background:

Despite preoperative evaluation with ceCT, the tumor load in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer to the liver is often underestimated. Positron emission tomography (PET) has been used in combination with the ceCT to improve identification of intra- and extrahepatic tumors in these patients. We compared ceCT and a novel fused PET/CT technique in patients evaluated for liver resection for metastatic colorectal cancer.

Methods:

Patients evaluated for resection of liver metastases from colorectal cancer were entered into a prospective database. Each patient received a ceCT and a PET/CT, and both examinations were evaluated independently by a radiologist/nuclear medicine physician without the knowledge of the results of other diagnostic techniques. The sensitivity and the specificity of both tests regarding the detection of intrahepatic tumor load, extra/hepatic metastases, and local recurrence at the colorectal site were determined. The main end point of the study was to assess the impact of the PET/CT findings on the therapeutic strategy.

Results:

Seventy-six patients with a median age of 63 years were included in the study. ceCT and PET/CT provided comparable findings for the detection of intrahepatic metastases with a sensitivity of 95% and 91%, respectively. However, PET/CT was superior in establishing the diagnosis of intrahepatic recurrences in patients with prior hepatectomy (specificity 50% vs. 100%, P = 0.04). Local recurrences at the primary colo-rectal resection site were detected by ceCT and PET/CT with a sensitivity of 53% and 93%, respectively (P = 0.03). Extrahepatic disease was missed in the ceCT in one third of the cases (sensitivity 64%), whereas PET/CT failed to detect extrahepatic lesions in only 11% of the cases (sensitivity 89%) (P = 0.02). New findings in the PET/CT resulted in a change in the therapeutic strategy in 21% of the patients.

Conclusion:

PET/CT and ceCT provide similar information regarding hepatic metastases of colorectal cancer, whereas PET/CT is superior to ceCT for the detection of recurrent intrahepatic tumors after hepatectomy, extrahepatic metastases, and local recurrence at the site of the initial colorectal surgery. We now routinely perform PET/CT on all patients being evaluated for liver resection for metastatic colorectal cancer.

Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT), a novel imaging technique, was prospectively evaluated in 76 patients with suspected liver metastases from colorectal origin. PET/CT enabled the detection of new lesions, particularly extrahepatic metastases, otherwise undetected by standard work-up. As a result, therapy was changed in a fifth of the patients.

Colon cancer is the second most frequent malignancy in the Western hemisphere after breast cancer in women and lung cancer in men. In the United States, about 150,000 patients are diagnosed with colon cancer each year, and more than 50,000 of these patients will develop liver metastases.1 Liver resection is the only therapeutic strategy that offers a chance of cure. This therapy has also gained increasing popularity over the past 2 decades due to improved surgical and peri-operative management with current mortality risks well below 5% in high-volume centers.2–4 Many surgeons have developed strategies to improve resectability of large tumors such as the induction of hypertrophy of an estimated small remnant liver volume by selective portal vein embolization5 and the downstaging6,7 of large liver tumors by chemotherapy. However, despite successful attempts at curative resection in many situations, long-term survival has remained somewhat disappointing, ranging between 25% and 40%.8–10

Most patients after a curative resection develop recurrent intra- or extrahepatic tumor manifestations.11 The main reason for these tumor recurrences after putative complete tumor removal is the presence of undetected tumor at the time of surgery. Currently, patients undergo an extensive preoperative work-up before liver resection to accurately define the hepatic lesions and to exclude the presence of extrahepatic disease. This includes spiral contrast-enhanced computed tomography (ceCT), magnetic resonance imaging, and colonoscopy. This strategy, however, is insufficient in view of the poor long-term results and the fact that many patients are still found to be unresectable at the time of surgery.

These shortcomings have prompted the development of new diagnostic tools. It has been shown for more than 50 years that most tumors have a higher utilization and metabolism rate of glucose.12,13 This has lead to the development of an imaging modality using positron emission tomography (PET) of 18F-labeled glucose, 2-[18-F]-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose (FDG), to detect cancer cells. FDG is transported into tumor cells by hexose transporters and is then phosphorylated by hexokinase to FDG-6-phosphate. FDG-6-phosphate cannot be further metabolized in most tumor cells, thereby it selectively accumulates in the cancer tissue.14 FDG-PET offers new information on specific metabolic features of cancer cells rather than anatomic data on the localization of a lesion.

Several recent studies have demonstrated a high sensitivity and specificity of FDG-PET scanning for several types of cancers,15–17 including colorectal cancer.18–20 Retrospective studies have also suggested that the availability of PET allows improved selection of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer to the liver, resulting in better survival after liver resection.21 For example, in 1 study, PET imaging detected extrahepatic tumor in 25% of patients found to have resectable hepatic metastases by conventional preoperative work-up.21 However, PET is limited by a poor resolution and poor anatomic localization of positive PET lesions. As a result, the diagnosis ultimately relies on a correlation between findings obtained on CT or magnetic resonance imaging and the PET scan. To overcome this limitation, a new technique combining the same imaging session data of a full-ring PET-scanner with a multi-detector row helical CT has been developed.22 With this novel technology, the PET-positive lesions are projected directly into the CT scan to obtain simultaneous functional and anatomic information. These theoretical advantages have recently been confirmed in lung cancer, where PET/CT was significantly more accurate in predicting the tumor stage than PET or CT alone.16

PET/CT technology was introduced in our center in April 2001, and patients with colorectal tumor referred for a liver resection underwent a PET/CT after conventional work-up. Data was prospectively collected to assess the ability of PET/CT to detect new tumor lesions and to evaluate how the availability of PET/CT imaging impacted on the selection of patients for surgery.

METHODS

Study Design

From January 2002 until July 2003, each patient being considered for liver resection for metastases from colorectal origin was included in the study. Cases with synchronous metastases were not present in this series. Conventional work-up included ceCT of the chest and abdomen, and when conventional imaging data from referring institutions was insufficient, that is, of poor quality or ceCT older than 15 days, a new ceCT was performed in our center. A colonoscopy was also required within 6 months prior to surgery. A PET/CT was obtained after completion of the conventional work-up. Any new lesion diagnosed on PET/CT was subsequently confirmed by percutaneous or surgical biopsies. The final decision to proceed with liver resection was based on all available data. In patients felt to have resectable lesions, a standard exploration of the abdominal cavity was performed, including routine intraoperative ultrasound by an independent investigator as well as biopsies of each lesion noted on ceCT or PET/CT. In patients who were considered nonoperable, the clinical course and serial ceCT (3 and 6 months) were used to conclusively establish the diagnosis of the initial ceCT and PET/CT findings. The PET/CT images were individually evaluated by a board-certified radiologist and nuclear medicine physician (T.F.H.) unaware of the other conventional imaging findings. The main end point was to assess how PET/CT may change the indications for surgery compared with conventional radiology, that is, ceCT alone. Secondary end points included the number of true- and false-positive and -negative PET/CT findings, the ability of ceCT and PET/CT to detect extrahepatic disease and recurrent liver tumor after hepatectomy, and finally the influence of chemotherapy on the detection of tumors by PET/CT. False-positive findings were defined as benign lesion, which were diagnosed as liver metastases. Liver metastases, which were missed by an imaging technique, were counted as false-negative findings.

ceCT Imaging Protocol

In-house ceCT imaging was performed with a multi-detector row scanner (Somatom Volume Zoom Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). For contrast-enhancement, 120 to 150 mL of contrast media (Imagopaque, Amersham, AS, Oslo, Norway) was injected intravenously. An arterial as well as a porto-venous phase of the liver was acquired according to the following parameters: 140 kV, 180mAs, collimation 4 × 1 to 4 × 2.5 mm, pitch 1.5 to 1.25, reconstruction interval (mm) 1 to 2, slice with 1.25 to 3 mm. Arterial phase imaging was performed with an automatic-bolus tracking system; the initiation of the porto-venous phase was set around 20 seconds after the end of the data acquisition of the arterial phase. Both scans covered the thorax and abdomen to the level of the groins.

PET/CT Imaging Protocol

All imaging and data acquisition was performed on a combined PET/CT system (Discovery LS, GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI) able to acquire CT images and PET data on the same patient in 1 session. A GE Advance NXi PET scanner and a multidetector-row helical CT (LightSpeed Plus) are integrated in this dedicated system. The table excursion permitted scanning of 7 contiguous PET sections covering 1011 mm. This gave adequate coverage from head to pelvic floor in all patients examined. The PET and CT data sets were acquired on 2 independent computer consoles, which were connected by an interface to transfer CT data to the PET scanner. For viewing of the images, the PET and CT data sets were transferred to an independent, PC-based computer workstation by DICOM transfer. All viewing of coregistered images were performed with a dedicated software system (eNTEGRA, ELGEMS, Haifa, Israel). Whereas PET images were acquired during free breathing and each image was obtained over multiple respiratory cycles, CT scans were performed during shallow breathing.

The patients were fasted for at least 4 hours before the intravenous administration of 10 mCi (370MBq) of FDG. Forty-five minutes postinjection, the combined examination started. CT data were acquired first. The patients were positioned on the table in a head-firs supine position. The arms of the patients were placed in an elevated position above the head to reduce beam-hardening artifacts. However, in patients unable to maintain this position, arms were positioned in front of the abdomen (n = 14). For the CT data acquisition, the following parameters were used: tube-rotation time 0.5 seconds per evolution, 140kV, 80 mA, 22.5 mm per rotation, slice beam pitch 1.5 (high-speed mode), reconstructed slice-thickness 4.25 mm, scan length 867 mm, and acquisition time 22.5 seconds per CT scan. No intravenous or oral contrast agents were used. After the CT data acquisition was completed, the tabletop was automatically advanced into the PET gantry, and acquisition of PET data was started at the level of the pelvic floor. Six incremental table positions were acquired with minimal overlap, thereby covering 867 mm of table travel. For each position, 35 2-dimensional nonattenuation-corrected scans were obtained simultaneously over a 5-minute period. No transmission scans were obtained because CT data were used for transmission correction. The technique for using CT data for attenuation correction has been described in detail elsewhere.23 The images were reconstructed with iterative reconstruction with 2 iterations and 28 subsets resulting in 35 2-dimensional sections over each axial field-of-view increment of 14.6 cm, resulting in a slice thickness of 4.25 mm. Image reconstruction matrix was 128 × 128 with a transaxial field of view of 49.7 × 49.7cm.

Data Analysis

The attenuation-corrected PET images, the CT images, and the coregistered PET/CT images were viewed simultaneously by a board-certified radiologist using eNTEGRA software. Image interpretation was based on the identification of regions with increased FDG uptake on the PET images and the anatomic delineation of all FDG-avid lesions on the coregistered PET/CT images. Furthermore, all CT images were viewed separately to identify additional lesions without FDG uptake using soft tissue, lung, and bone window leveling.

Statistical Analysis

Differences in the ability to detect intrahepatic and extrahepatic lesions between the CT scan and PET/CT were calculated by the χ2 test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The statistical analysis was performed with the Statistical Package and Software Solution 9.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) software.

RESULTS

Demographics

Seventy-six patients (52 men, 24 women) with a median age of 63 years (range 35–78 years) were included in the study. Each patient was evaluated for resectability of metastatic colorectal cancer to the liver and received a ceCT and a PET/CT within a period of 2 weeks. The median time between colorectal resection and initial presentation was 14 months (range 3–25 months). Sixty-two patients received chemotherapy after the colorectal cancer surgery with a median interval between last chemotherapy and PET/CT of 3 months (range 7 days to 15 months). The median follow-up of patients was 16 months (6 months to 3 years).

The data was analyzed in a step-by-step manner.1 First, a correlation of the ceCT and PET/CT findings was performed, including an analysis of all additional information provided by PET/CT. We then focused on2 identification of each positive and negative finding with ceCT and PET/CT,3 the ability of PET/CT to identify metastases at different extrahepatic sites and at the site of local recurrence after hepatectomy, and4 the potential effect of chemotherapy on false-negative PET/CT findings. Finally, as the main end point of the study, we assessed the impact of PET/CT on the management of patients with liver metastases.

How Does ceCT Compare to PET/CT Regarding the Detection of Intra- and Extrahepatic Metastases?

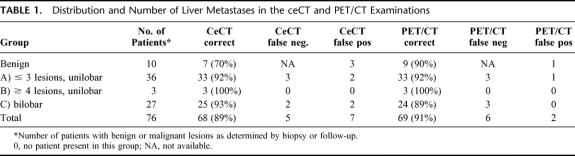

The presence of liver metastases was evaluated and allocated into the following groups: (A) unilobar disease up to 3 lesions; (B) unilobar disease with 4 or more lesions; and (C) bilobar disease. As shown in Table 1, liver lesions were diagnosed as benign in 8 patients by ceCT and in 14 patients by PET/CT. About half of the remaining patients were in group A with either diagnostic modality, less than 5% were in group B, and about a third of patients were in group C. Therefore, no difference was noted between ceCT and PET/CT regarding the detection of intrahepatic metastases according to the classification used. Local recurrence at the site of the colorectal primary tumor was found in 9 patients (11%) in the ceCT and in 15 patients (20%) in the PET/CT (P = 0.27, Fisher's exact test). The presence of extrahepatic disease was identified by ceCT in 24 patients (31%), whereas PET/CT identified 34 patients (45%) with extrahepatic lesions (P = 0.13). False-positive and -negative findings are presented below.

TABLE 1. Distribution and Number of Liver Metastases in the ceCT and PET/CT Examinations

What Was the Incidence of False-Negative and False-Positive Findings With ceCT and PET/CT?

An analysis of false-positive and -negative ceCT and PET/CT findings was performed. The final diagnosis was based on intraoperative findings including a comprehensive ultrasound evaluation, histology of the resected liver and other biopsies, and follow-up with serial ceCT in all patients, including those who did not undergo surgery.

Ten patients (13%) had only benign liver lesions without evidence of malignancy. ceCT correctly identified 7 patients as cancer-free with false-positive results in 3 patients (2 adenomas and 1 hemangioma) (specificity 70%). PET/CT ruled out cancer in 9 patients, with 1 patient being false-positive (liver abscess) (specificity 90%, P = 0.58). Among the 66 patients with documented liver metastases, ceCT missed hepatic lesions in 3 patients (5%) and provided false-positive results in 1 case (sensitivity 95%). By contrast, PET/CT did not detect the liver metastasis in 6 patients (9%) (sensitivity 91%).

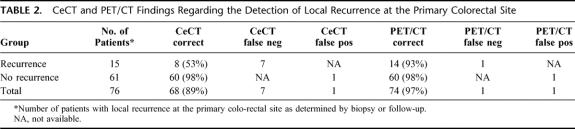

Local recurrence at the site of previously resected colorectal tumor was present in 15 patients. ceCT missed the diagnosis or provided inconclusive information in 7 patients (53%; sensitivity 53%), whereas PET/CT allowed identification of 14 of the 15 patients, with 1 patient being false-negative (7%, sensitivity 93%, P = 0.03) (Table 2).

TABLE 2. CeCT and PET/CT Findings Regarding the Detection of Local Recurrence at the Primary Colorectal Site

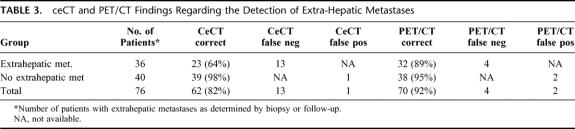

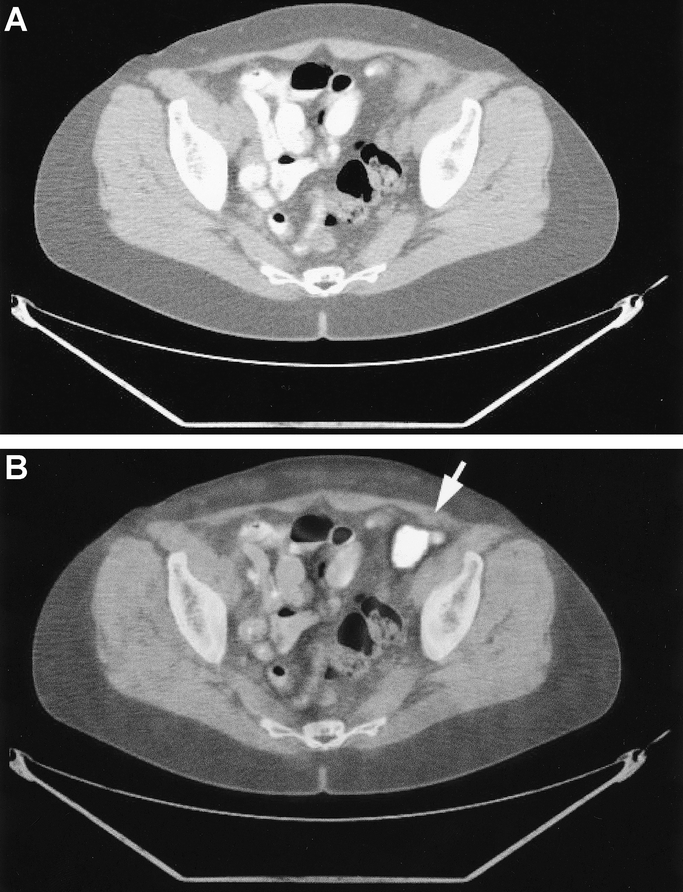

Extrahepatic metastases were present in 36 of the 66 patients (55%) (Fig. 2). ceCT failed to diagnose extrahepatic metastases in 13 of the 36 patients (36%) (sensitivity 64%), whereas PET/CT did not diagnose extrahepatic lesions in only 4 (11%) of the 36 cases (sensitivity 89%; P = 0.02) (Table 3).

FIGURE 2. Local recurrence at the site of the primary colon cancer. The diagnosis was missed by ceCT findings alone, and the unclear hypodense lesion in the liver was not classified as tumor recurrence (a). PET/CT demonstrated FDG uptake, establishing the presence of a tumor recurrence (b).

TABLE 3. ceCT and PET/CT Findings Regarding the Detection of Extra-Hepatic Metastases

How Does PET/CT Compare to ceCT in the Detection of Local Recurrence in the Liver After Hepatectomy?

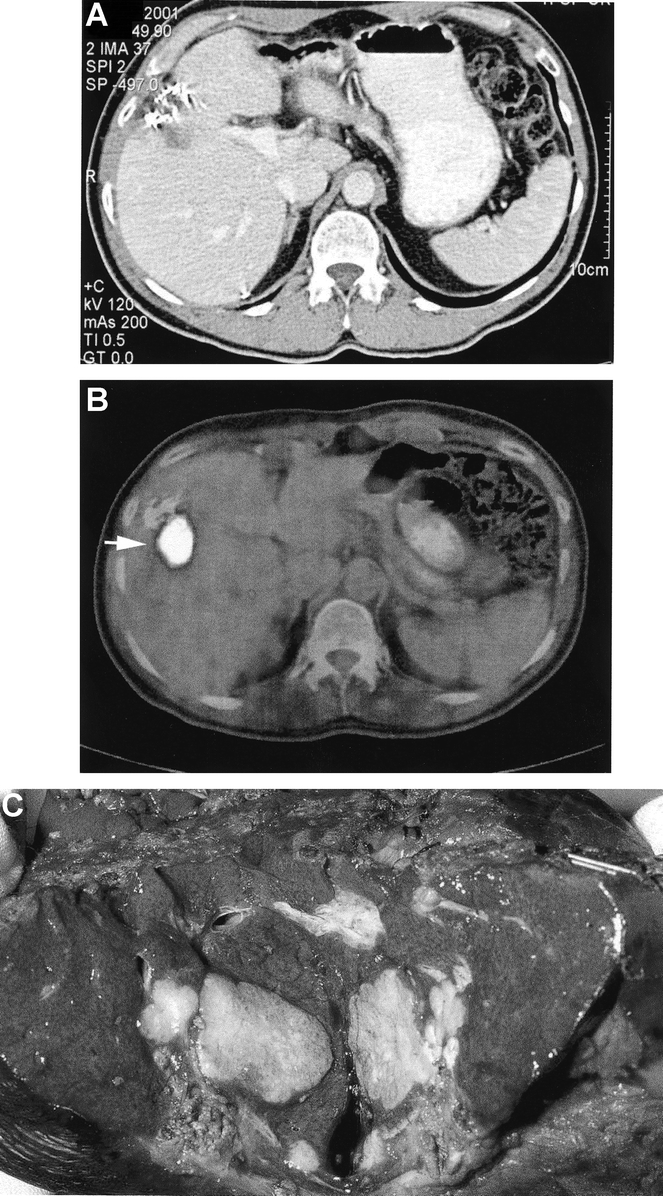

The detection of tumor recurrence within the liver after hepatectomy remains difficult. Accurate evaluation is important as false-positive may result in unnecessary intervention, and false-negative may prevent the possibility of curative reresection or ablation therapy. Local recurrence within the liver was suspected on the basis of serial CeCT in 18 patients. Local recurrence was confirmed within the liver in 9 patients (50%), as established at the completion of the study by histology or follow-up. The other 9 patients had changes unrelated to recurrent cancer. PET/CT identified all 9 patients with local recurrence, and provided a false-positive finding in only 1 patient (sensitivity 100%, specificity 89%). Thus, the specificity of ceCT in identifying recurrent disease was 50%, compared with 100% for PET/CT (P = 0.04, Fisher's exact test) (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1. Recurrence of a colon cancer metastasis in the liver after previous liver resection. The ceCT (a) shows a hypodense lesion of unclear etiology. The PET/CT (b) demonstrates FDG uptake highly suggestive for tumor recurrence. The patient was reoperated and the tumor recurrence was confirmed by pathology (c).

What Is the Ability of PET/CT to Identify Tumors at Specific Extrahepatic Locations?

Because the ability to detect extrahepatic metastases by ceCT or PET/CT could be dependent on the location, we separately evaluated metastases in the lung, portal, or para-aortic lymph nodes, as well as in bone.

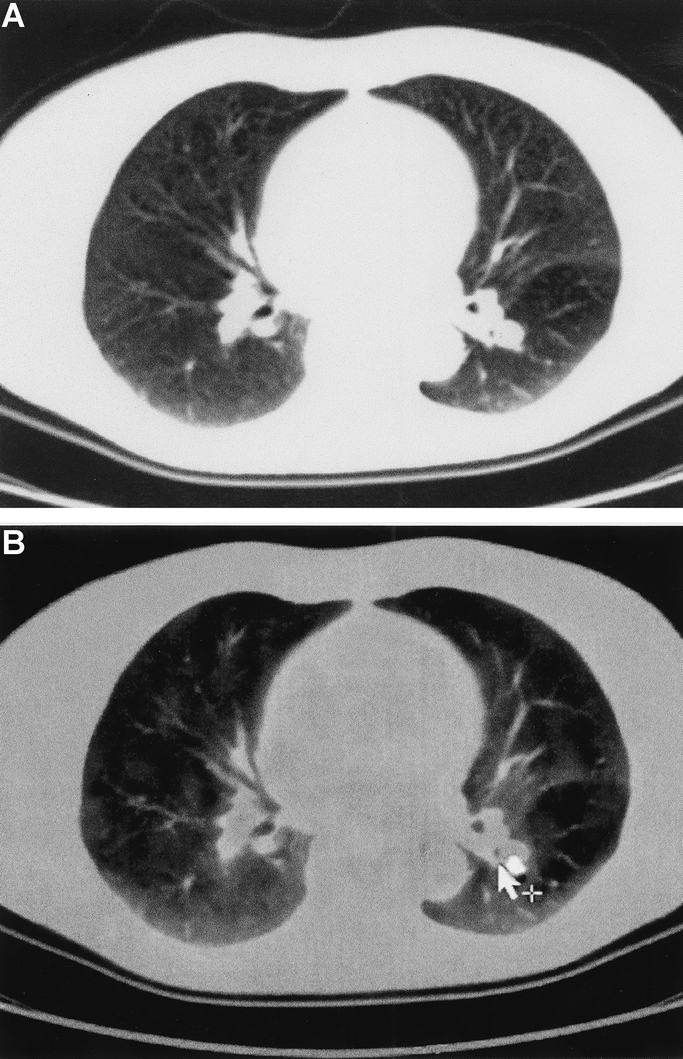

Lung metastases were present in 18 patients and were correctly diagnosed in each patient by PET/CT (sensitivity 100%). By contrast, ceCT failed to detect lung metastases in 4 (22%) of the 18 patients (sensitivity 78%, P = 0.1) (Fig. 3). Portal and para-aortic lymph node metastases were present in 13 patients. ceCT failed to identify these lesions in 7 patients (54%, sensitivity 46%), whereas PET/CT missed this diagnosis in 3 patients (23%) (sensitivity 77%, P = 0.4). Bone metastases were noted in 4 patients at the time of the initial presentation. These bone lesions were missed by ceCT in 2 patients and by PET/CT in 1.

FIGURE 3. Lung metastasis from colon cancer. The etiology of the unclear lesion located at the left hilum remains unclear in the ceCT (a) and allows various differential diagnoses. FDG uptake in the PET/CT indicates a thoracic metastasis of the colon cancer (b).

Does the Use of Chemotherapy Before PET/CT Influence FDG Uptake of Colorectal Metastases?

It has been suggested that the use of chemotherapy within a month of a PET examination may decrease the sensitivity of PET scan in detecting tumors24, although others have challenged this shortcoming.25 To address this issue, we determined the number of false-negative FDG-uptake in patients with previous chemotherapy versus those without previous chemotherapy administration. Eighteen received chemotherapy within 1 month prior to PET/CT. FDG uptake was absent in the liver metastases in 5 patients (28%) in the group with recent chemotherapy (sensitivity 72%) and in 1 of 58 patients (5%) in the group without recent chemotherapy (sensitivity 98%, P = 0.14, Fisher's exact test).

Extrahepatic metastases were present in 9 of the 18 patients with recent chemotherapy. No FDG uptake was noted in 3 of these 9 patients (sensitivity 66%). By contrast, among the 58 patients without recent chemotherapy, 27 had extrahepatic metastases. FDG uptake was negative in 1patient (sensitivity 96%; P = 0.05, Fisher's exact test).

Similar results were found regarding local recurrence at the site of previous colorectal surgery. Such recurrence was present in 3 patients (17%) in the recent chemotherapy group. FDG uptake was negative in 1 of these 3 patients (sensitivity 66%), whereas documented local recurrence remained FDG-negative in only 1 of 12 patients in the group without chemotherapy (sensitivity 92%; P = 0.08). This patient was diagnosed as a local recurrence by ceCT and PET/CT, despite a negative FDG-uptake, because of an obvious large tumor mass infiltrating the sacrum.

How Does the Availability of PET/CT Impact on the Management of Patients With Liver Metastases?

The main end point of the study was to determine whether the availability of PET/CT may influence the therapeutic strategy in patients with suspected liver metastases. In all 76 patients, a treatment plan was defined after the ceCT examination and re-evaluated after obtaining the PET/CT data. In 60 patients (79%), PET/CT did not change the therapeutic strategy based on the ceCT findings alone. In 16 patients (21%), the findings on PET/CT resulted in a treatment change. Ten patients were considered resectable by ceCT, whereas PET/CT demonstrated extensive extrahepatic disease representing a contraindication for surgery. In the 6 remaining patients, ceCT was negative for extrahepatic tumor, whereas PET/CT indicated positive nodes in the hepato-duodenal ligament. In these cases, the surgical strategy was changed to a liver resection and removal of the peri-portal nodes, as part of an additional study evaluating the role of surgery in this particular population of patients. Taken together, the addition of PET/CT findings resulted in a change in therapy (ie, not candidate for a curative resection) in a fifth of the patients.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study investigating a novel fusion technique of combined PET and CT scan for the evaluation of patients with liver metastases from colorectal origin. PET/CT and ceCT provided comparable findings for the detection of primary liver metastases, but PET/CT was more sensitive and specific in detecting extrahepatic metastases including local recurrence at the site of colorectal cancer as well as local recurrence within the liver after hepatectomy. The information provided by PET/CT resulted in a change in the therapeutic strategy in about a fifth of the patients.

The detection of liver metastases has improved over the past decade with the advance of ceCT, with current reported sensitivity and specificity ranging between 65% and 97%.26–28 However, the detection of extrahepatic lesions with low contrast enhancement, such as portal and para-aortic metastases, is difficult by ceCT.29 Furthermore, after previous hepatectomy, tumor recurrence within the liver is often difficult to diagnose due to nonspecific postoperative changes. The development of the PET scan has offered a new diagnostic option through the visualization of tumor metabolic activity rather than anatomic structures. A few authors have evaluated conventional PET scan in patients with liver metastases from colorectal origin.18,25,30 For example, Ruers et al25 reported on 51 patients, in whom a CT scan and a conventional PET scan were performed in the evaluation of liver metastases from colorectal origin. They identified extrahepatic disease in 22% of the patients by PET scan, which were missed by ceCT. However, intrahepatic metastases were more often identified by ceCT than PET (sensitivity 80% vs. 65%). Similarly, Fong et al30 described a low sensitivity of the conventional PET scan, as only 37 out of 52 patients with liver metastases had positive PET findings, although PET enabled identification of 10 patients with otherwise undetected extrahepatic disease.

Conventional PET scanning is associated with several shortcomings. The major drawback relates to the poor resolution of the PET images, making exact localization of FDG uptake difficult. For example, a right adrenal gland metastasis can be misinterpreted as a liver metastasis.18 Additionally, confirmation of a positive FDG uptake by histology is sometimes impossible because of the lack of morphologic information. The new PET/CT technique allows exact identification of the lesions, which enables accurate biopsies and targeted surgery to be performed. These advantages were recently confirmed by Cohade et al31 in a series of 45 patients with primary colorectal tumor. PET/CT increased the accuracy of the diagnosis by 30% and improved the certainty of the tumor location by 25%. Similarly, we also noted that PET alone could not localize metastases with certainty in 45% of our population, whereas PET/CT identified the precise localization in each patient (data not shown). Positive PET/CT findings outside of the liver may not always result in denial of surgery, but it may help in targeting additional resection and direct specific studies in a defined group of patients. In our series of 76 patients, additional extrahepatic lesions were shown on PET examination in 16 patients (21%). In 6 cases, we opted to proceed with the liver resection including additional removal of peri-portal PET/CT-positive lymph nodes. It has been suggested that R0 liver resection with proximal peri-portal lymph node metastasis are associated with an acceptable outcome.32

In this study, we found that ceCT and the PET/CT provided identical information on the presence of liver metastases in patients without previous hepatectomy. The high sensitivity and specificity of ceCT for the detection of liver metastases is related to the intravenous contrast enhancement of the liver, which enables an accurate delineation of intrahepatic lesions. On the other hand, the detection of FDG uptake in the liver is somewhat limited because normal hepatocytes contain a high hexokinase activity and thereby may incorporate FDG.29 Thus, tumors with low metabolic activity might be diagnosed as false-negative on the basis of FDG uptake, but such lesions are usually detected by the fused CT findings. In contrast, PET/CT was significantly superior to ceCT in detecting local recurrences within the liver after hepatectomy. In half of the patients with local recurrences in the liver, ceCT provided no or inconclusive information. In contrast, each recurrent metastasis demonstrated positive FDG uptake on PET/CT. This finding is not surprising because it is well know that differentiation between postoperative changes after hepatectomy and tumor recurrence based on morphologic findings alone is difficult. By contrast, new intrahepatic metastases distant from the site of the previous liver resection were equally detected by ceCT and PET/CT (data not shown).

The ability of the PET/CT to detect extrahepatic metastases was different for various tumor locations. Excellent results were achieved for lung metastases, where the PET/CT enabled to detect each lesion, whereas ceCT missed one fifth of the lung lesions. The important role of PET/CT for the detection of lung cancer has also been confirmed by others. Lardinois et al16 reported an increased accuracy of PET/CT compared with ceCT or PET alone in patients with small cell lung cancer. For the detection of para-aortic and porta lymph nodes, the sensitivity of PET/CT was lower (77%) although still superior to ceCT (sensitivity 46%). In contrast, both imaging techniques—ceCT and PET/CT—were unreliable for the detection of bone and peritoneal metastases. A more precise evaluation of bone lesions would require a bone scintigraphy, which is usually not performed because of the low incidence of bone involvement in patients with resectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Peritoneal lesions can be detected by laparoscopy prior to laparotomy, and our results indicate that PET/CT cannot replace staging laparoscopy for the diagnosis of peritoneal lesions.

Local recurrence at the site of the primary colorectal cancer is often missed by conventional ceCT, and positive findings are difficult to interpret due to the inherent changes related to previous colectomy and sometimes to postoperative infection. In this study, 15 patients (20%) had a local colorectal recurrence at the time of evaluation for liver resection. ceCT enabled the detection of only half of these patients, whereas all but 1 (93%) were correctly diagnosed by PET/CT. Of note, the patient with a false-negative lesion received chemotherapy within a week of the CT/PET scan. A potential pitfall of PET/CT is the inability to differentiate between tumor and chronic infection, because both situations are associated with an increased FDG uptake. Although no false-positive findings regarding local recurrence were present in the current series, this shortcoming needs to be considered. Whether PET/CT can obviate the need for colonoscopy remains to be demonstrated, but it is likely that PET/CT is superior because local recurrence is often extraluminal, which may remain undetected by endoscopy.

Although our study demonstrates that PET/CT provides valuable new information, several shortcomings need to be highlighted. FDG uptake is often not detected in small tumors (eg, <5 mm), which are also often missed on ceCT. There are currently no tests that can prevent such false-negative findings. As mentioned above, there are also false-positive findings, particularly in the setting of infection because FDG uptake will occur in infected lymph nodes.19,30 Furthermore, the clinical history should be well known because high blood glucose levels or recent chemotherapy may prevent FDG uptake by cancer cells. In this study, we found that the use of chemotherapy within 1 month of PET/CT resulted in a high incidence of false-negative results. Therefore, FDG uptake seems to be unreliable in patients with recent chemotherapy. However, whereas FDG uptake was negative, most of these lesions were seen by the fused CT findings. Thus, if the clinician is aware of this limitation, findings on PET/CT can still be of value.

In this study, we performed PET/CT without the use of intravenous contrast; therefore intrahepatic vascular structures were poorly delineated. This information is crucial in the planning of the surgical strategy. In addition, infiltration and thrombosis of portal vein branches are important pieces of information with prognostic significance. As a result, we now evaluate PET/CT with intravenous contrast, because this may obviate the need for additional ceCT or magnetic resonance imaging, or perhaps colonoscopy. Such a strategy would be attractive, enabling a one-step diagnostic procedure with a potential reduction in cost.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that PET/CT provides important additional information in patients with presumed resectable colorectal metastases to the liver, resulting in a change of therapy in a fifth of patients. The most significant additional information relates to the accurate detection of extrahepatic spread of tumor. Also, PET/CT was particularly valuable in detecting local recurrence at the margin of a previous liver resection and at the site of the primary colorectal surgery. Future studies should evaluate whether PET/CT with the simultaneous use of intravenous contrast would enable an accurate anatomic staging of patients with liver metastases without the need for additional tests.

Discussions

Dr. Jaeck: Thank you for the opportunity to discuss this very nice paper. I think that you have to be congratulated for this very interesting study. It is the first prospective study comparing contrast CT and PET-CT in the preoperative evaluation of colorectal liver metastases. There was a real need to perform such a study. The main end point of the study was to evaluate how the PET-CT could change the surgical indications. You showed that in 79% of the patients, it did not. For the remaining 16 patients, the findings resulted in a change of treatment; however, 6 were still considered resectable, but with extrahepatic disease resection, and finally only 10 were not operated.

My first question concerns the cost-effectiveness of PET-CT. My second question concerns the 6 patients that you decided to operate on despite the presence of extrahepatic disease. Were you able to differentiate the PET-CT-positive nodes in the hepato-duodenal ligament from positive nodes around the celiac axis, as we could show previously that only proximal periportal lymph node metastases are associated with acceptable outcome? My main concern is about the 10 patients you decided not to operate. Indeed, if the extrahepatic disease could have been resected, it would suppress wrongly for these patients any hope for cure. My question is, did you use additional exploration such as biopsy to confirm the results of PET-CT and to avoid any false-positive? Secondly, what is your policy concerning resectable extra-hepatic disease, as you did not mention this aspect in your selection criteria?

Finally, it would be very interesting to compare CT to PET-CT with simultaneous use of intravenous contrast, which will probably add more information.

Dr. Selzner: Dr. Jaeck, thank you for your thoughtful comments. Cost-effectiveness was not an end point in our study, and therefore we cannot give you detailed information on this issue. However, since surgery was avoided in 10 out of 66 patients, substantial cost savings might be expected. Second, because of the high anatomic resolution of the PET/CT, we could convincingly differentiate PET positive lymph nodes in the hepato-duodenal ligament from those around the celiac axis. Third, in our series a biopsy was performed in each PET/CT positive finding, which was not seen by conventional ceCT. Fourth, we consider extrahepatic disease as a contraindication for liver resection, except for resectable lung lesions and proximal periportal lymph node metastases.

Dr. Senninger: Thank you very much for your presentation. You are well ahead of us with an instrument like this; we have a PET/CT in Munster since January this year.

I have 1 comment and 2 short questions. The comment would be that in our experience we do not trust pelvic CT guided biopsies if they are negative. Whatever they show, during the exploration you can have a safe look at the liver and at the same time you can investigate if there is a leakage of the anastomosis that could result in a false-positive PET finding. Can you describe the effects of a previous thermo-ablation in the liver on PET results, because the surrounding inflammation could give a false-positive PET enhancement? Second, could you please highlight the value of the PET/CT for the differentiation of benign and malignant lesions? Every liver center has 1 or 2 patients per year where benign lesions are thought to be benign but turn out to be a malignant tumor.

Dr. Selzner: No patient received thermo-ablation prior to the PET/CT in our series. However, this is an important question to address in future studies. Concerning your second question, our study focused on patients with suspected liver metastases, and in this population PET/CT was superior to ceCT in identifying the nature of the liver lesion. A series of patients with suspected benign liver lesions would be necessary to properly address the role PET/CT in securing the benignity of such lesions.

Dr. Neuhaus: Part of my questions has already been answered. I would, however, like to ask you what you would decide and how you would proceed if 6 or 9 months after rectal excision or low anterior resection you have a single resectable liver metastasis and a positive PET finding in the pelvis? Would you deny a possibly life-saving operation because of a positive PET result?

Dr. Selzner: Dr. Neuhaus, thank you for this question. At this point, curative liver resection should not be denied on the basis of FDG-positive lesions alone in the pelvis or elsewhere. A histologic confirmation has to be obtained by percutaneous or open biopsy, and the treatment adjusted accordingly.

Dr. Lerut: I would like to challenge a little bit your results on detecting the lung metastasis. I was surprised that you had 4 patients in which the lung metastasis were “missed on CT scan,” and I wonder whether they really were missed or whether it was just a confirmation by PET of an already on CT scan suspicious lesion. Indeed, if the PET shows a metastasis, you would expect that the diameter would be like at least 1 cm or more, and those are lesions that with modern spiral CT scan no radiologist would miss today. Secondly, along the same lines, would you agree that multislice spiral CT for the subcentimetric lesions is still more accurate than PET or PET-CT, because these lesions do not have sufficient critical mass to show up on the PET scan?

Dr. Selzner: Thank you for this important question. I reported here the data as evaluated by our nuclear medicine/radiologist author (T.F.H.) in a blind manner. I would like to let Professor Clavien address this issue and conclude the discussion.

Dr. Clavien: Dr. Lerut, this is an important point, which we have discussed in length with our “imaging” colleagues. PET/CT is a fusion of PET plus CT images, and the FDG-uptake has to be evaluated in combination with the CT finding. The fusion of both techniques was better than the additive information of each picture. CT missed these lesions because they were not enough suspicious regarding shape, size, and location. Your next question is whether ceCT is better than CT plus PET/CT for small lesions. This might be true today, although not apparent in our study. However, the forthcoming availability of PET/ceCT (ie, CT with intravenous contrast) will obviously be better than ceCT alone, and PET/ceCT may become the only test needed to assess these patients preoperatively. I would like to conclude that we (surgeons) should not see PET/CT as a tool which only leads to denial of surgery to many patients. PET/CT offers new opportunities to better target our therapy, and we may well find that patients with extrahepatic lesions other than in the lung and periportal nodes may also benefit from surgery. I believe that PET/CT should now be included in each trial to better secure homogeneity of the studied populations.

Footnotes

M.S. and T.F.H. contributed equally to this work.

Reprints: Pierre-A. Clavien, MD, PhD, FACS Professor of Surgery Department of Surgery University Hospital Zürich Rämistrasse 10, 8091 Zurich, Switzerland. E-mail: Clavien@chir.unizh.ch.

REFERENCES

- 1.Parker S, Tong T, Bolden S, et al. Cancer statistics. Cancer J Clin. 1997;47:5–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selzner M, Clavien PA. Resection of liver tumors: Special emphasis on neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy. In: Clavien PA, editor. Malignant Liver Tumors: Current and Emerging Therapies. Malden: Blackwell Science; 1999:137–149. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belghiti J, Hiramatsu K, Benoist S, et al. Seven hundred forty-seven hepatectomies in the 1990s: an update to evaluate the actual risk of liver resection. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clavien PA, Selzner M, Rüdiger H, et al. A prospective randomized study in 100 consecutive patients undergoing major liver resection with vs. without ischemic preconditioning. Ann Surg. 2003;238:843–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azoulay D, Castaing D, Smail A, et al. Resection of nonresectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer after percutaneous portal vein embolization. Ann Surg. 2000;231:480–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clavien PA, Selzner N, Morse M, et al. Downstaging of hepatocellular carcinoma and metastasis from colorectal cancer by selective intra arterial chemotherapy. Surgery. 2002;131:433–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bismuth H, Adam R, Levi F, et al. Resection of nonresectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Surg. 1996;224:509–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Figueras J, Farran L, Benasco C, et al. Vascular occlusion in hepatic resections in cirrhotic rat livers: an experimental study in rats. Liver Transplant Surg. 1997;3:617–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fong Y, Fortner J, Sun RL, et al. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg 1999;230:309–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Millikan KW, Staren ED, Doolas A. Invasive therapy of metastatic colorectal cancer to the liver. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77:27–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheele J, Stangl R, Altendorf-Hoffmann A. Indicators of prognosis after hepatic resection for colorectal secondaries. Surgery. 1991;110:13–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warburg O, Wind F, Neglers E. On the Metabolism of Tumors in the Body. London: Constable; 1930. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Som P, Atkins H, Bandopadhyay D, et al. A fluorinated glucose analoge, 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (F18): nontoxic tracer for rapid tumor detection. J Nucl Med 1980;21:670–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis P, Griffin S, Marsden P, et al. Whole-body 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in preoperative evaluation of lung cancer. Lancet. 1994;344:1265–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lowe V. Positron emission tomography scanning in lung cancer. Resp Care Clin North Am. 2003;9:119–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lardinois D, Weder W, Hany T, et al. Staging of non-small-cell lung cancer with integrated positron-emission tomography and computed tomography. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2500–2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prichard R, Hill A, Skehan S, O'Higgins N. Positron emission tomography for staging and management of malignant melanoma. Br J Surg. 2002;89:389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai D, Fulham M, Stephen M, et al. The role of whole-body positron emission tomography with [18]fluorodeoxyglucose in identifying operable colorectal cancer metastases to the liver. Arch Surg. 1996;131:703–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desai C, Zervos E, Arnold M, et al. Positron emission tomography affects surgical management in recurrent colorectal cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Topal B, Flamen P, Aert R, et al. Clinical value of whole-body positron emission tomography in potentially curable colorectal liver metastases. EJSO. 2001;27:175–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandez FG, Drebin JA, Linehan DC, Dehdashti F, Siegel BA, Strasberg SM. Five-year survival after resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer in patients screened by positron emission tomography with F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose. Ann Surg. 2004;240:438–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hany T, Steinert H, Goerres G, et al. PET diagnostic accuracy: improvement with in-line PET-CT system: Initial results. Radiology. 2002;225:575–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamel E, Hany TF, Burger C, et al. CT vs 68Ge attenuation correction in a combined PET/CT system: evaluation of the effect of lowering the CT tube current. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2002;29:346–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Findlay M, Young H, Cunningham D, et al. Noninvasive monitoring of tumor metabolism using fluorodeoxyglucose and positron emission tomography in colorectal cancer liver metastases: correlation with tumor response to fluorouracil. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:700–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruers T, Neeleman N, Jager G, et al. Value of positron emission tomography with [F-18]fluorodeoxyglucose in patients with colorectal liver metastases: a prospective study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:388–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schiepers C, Penninckx F, Vadder N, et al. Contribution of PET in the diagnosis of recurrent colorectal cancer: comparison with conventional imaging. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1995;21:517–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vitola J, Delbeke D, Sandler M, et al. Positron emission tomography to stage suspected metastatic colorectal carcinoma to the liver. Am J Surg. 1996;171:21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson K, Bakhsh A, Young D, et al. Correlating computed tomography and positron emission tomography scan with operative findings in metastatic colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:354–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beets G, Penninckx F, Schiepers C, et al. Clinical value of whole-body positron emission tomography with [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose in recurrent colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 1994;81:1666–1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fong Y, Saldinger P, Akhurst T, et al. Utility of [18]F-FDG positron emission tomography scanning on selection of patients for resection of hepatic colorectal metastases. Am J Surg. 1999;178:282–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohade C, Osman M, Leal J, et al. Direct comparison of (18)F-FDG PET and PET/CT in patients with colorectal carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1797–1803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jaeck D, Nakano H, Bachellier P, et al. Significance of hepatic lymphe node involvement in patients with colorectal liver metastases: a prospective study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:430–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]