Abstract

Heat-shock protein 90 (Hsp90) is a molecular chaperone that plays a key role in the conformational maturation of various transcription factors and protein kinases in signal transduction. Multifunctional ribosomal protein S3 (rpS3), a component of the ribosomal small subunit, is involved in DNA repair and apoptosis. Our data show that Hsp90 binds directly to rpS3 and the functional consequence of Hsp90-rpS3 interaction results in the prevention of the ubiquitination and the proteasome-dependent degradation of rpS3, subsequently retaining the function and the biogenesis of the ribosome. Interference of Hsp90 activity by Hsp90 inhibitors appears to dissociate rpS3 from Hsp90, associate the protein with Hsp70, and induce the degradation of free forms of rpS3. Furthermore, ribosomal protein S6 (rpS6) also interacted with Hsp90 and exhibited a similar effect upon treatment with Hsp90 inhibitors. Therefore, we conclude that Hsp90 regulates the function of ribosomes by maintaining the stability of 40S ribosomal proteins such as rpS3 and rpS6.

INTRODUCTION

Heat-shock proteins (Hsp) are ubiquitously expressed, highly conserved proteins among the eukaryotes and are involved in the folding of newly synthesized proteins and their refolding under conditions of denaturing stress. Although many of the specific functions of heat-shock proteins and their cochaperones in these processes remain largely unknown, their chaperoning function appears essential for the prevention of protein misfolding and aggregation.

Among the heat-shock proteins, Hsp90 is abundant in the cytosols of eukaryotes and prokaryotes and in contrast to other chaperones, a number of substrates are known to contain Hsp90 (Richter and Buchner, 2001). Studies of eukaryotes have revealed that these Hsp90 client proteins include a variety of transcription factors (aryl hydrocarbon receptor, glucocorticoid receptor, p53; Sanchez et al., 1985; Coumailleau et al., 1995; Nagata et al., 1999), protein kinases (Akt, Raf-1, ErbB2, Lck; Schulte et al., 1995; Sato et al., 2000; Xu et al., 2001; Giannini and Bijlmakers, 2004), and cellular enzymes (eNOS, telomerase; Garcia-Cardena et al., 1998; Holt et al., 1999).

The function of Hsp90 is associated with a group of Hsp90-binding cochaperones that variously assist the recruitment or release of client proteins; these Hsp90-binding cochaperones modulate their interactions through the ATPase-coupled chaperone cycle (Pearl and Prodromou, 2001). Hop (hsp-organizing protein) is a unique cochaperone that interacts with both Hsp70 and Hsp90 chaperones. Because Hop contains two TPR (tetratrico-peptide repeat) domains, it is able to associate with both Hsp90 and Hsp70 simultaneously (Scheufler et al., 2000). Another cochaperone of this kind is CHIP (carboxyl-terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein), which was identified as a candidate for a ubiquitin ligase involved in the modification of the client proteins of Hsp90 (McClellan and Frydman, 2001; Meacham et al., 2001). Although its mechanism is not clearly understood, CHIP was found to induce ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation of ErbB2 (Zhou et al., 2003), glucocorticoid receptor (Connell et al., 2001), and nNOS (Peng et al., 2004).

The N-termini of the Hsp90 family contain an ATP-binding domain that is very important for its function as a chaperone. ATP binding and hydrolysis are required for the protein folding and the release of activated substrates. Several natural products, including geldanamycin and 17-AAG, natural ansamycin antibiotics, bind tightly to the Hsp90 ATP/ADP pocket (Prodromou et al., 1997; Stebbins et al., 1997). The occupancy of the pocket by these drugs prevents ATP binding and completion of client protein refolding.

Ribosomal protein S3 (rpS3) is a component of the 40S ribosomal small subunit. The cross-links between rpS3 and eukaryotic initiation factors, eIF-2 (Westermann et al., 1979) and eIF-3 (Tolan et al., 1983), have been reported previously. Its genomic structure was completely characterized by the verification of the presence of the functional U15b small nucleolar RNA gene in its intron (Lim et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2005). Although the ribosome is widely known as the protein-synthesizing machine, numerous ribosomal proteins are bifunctional; that is, they not only constitute integral components of the ribosome, but also carry out other tasks in the cell that are often unrelated to the mechanics of protein synthesis (Naora, 1999; Zimmermann, 2003). RpS3 is a ribosomal protein that participates in the processing of UV-induced DNA damage and other DNA damage, functioning as a general base-damage endonuclease (Kim et al., 1995; Kim et al., 2005). Furthermore, mammalian rpS3 has been shown to induce apoptosis in some cell lines (Jang et al., 2004). It was recently shown that rpS3 appears to be phosphorylated by Erk in proliferating cells (Kim et al., 2005). Overall, rpS3 seems to be involved in translation, DNA repair, and apoptotic pathways. In regards to its multiple functions in cells, rpS3 should be regulated by diverse cellular-signaling molecules. Using a yeast two-hybrid system in this study, we investigated the partner proteins that interact with rpS3, and found that Hsp90 was an interacting protein. This finding was reconfirmed not only by in vitro and in vivo bindings, but also by subcellular localization. Our study showed that, when Hsp90 inhibitors blocked the chaperoning activity, rpS3-Hsp90 binding was reduced early in the process, but had an effect on the stability of rpS3 at a later point in the process. The degradation of rpS3 by treatment with Hsp90 inhibitors was related to the ubiquitin-dependent proteasomal pathway accompanied by the recruitment of Hsp70. Moreover, another 40S ribosomal protein, such as rpS6, also interacted with Hsp90. These results suggest that 40S ribosomal proteins are the client proteins of Hsp90; these proteins may regulate the function and biogenesis of the ribosome through their interactions with 40S ribosomal proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and Antibodies

Protein A-Sepharose was purchased from Roche Molecular Biochemicals (Mannheim, Germany). Geldanamycin (GA; 345805), MG132 (474790), ALLN (208719), and radicicol (553400) were purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). Anti-rabbit Hsp90 (sc-7947), anti-mouse Hsp70 (sc-24), anti-rabbit GST (sc-459), anti-mouse GFP (sc-9996), anti-mouse HA (sc-7392), anti-mouse phospho-ERK (sc-7383), anti-mouse actin (sc-8432), and anti-mouse ubiquitin (sc-8017) antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-mouse FLAG (F-3165) was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Anti-human rpS3 was purchased from BioInstitute (Korea University, Seoul, South Korea). ECL reagents were purchased from Pierce (34078; Rockford, IL). The glutathione-Sepharose 4B was obtained from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (17–0756-01; Piscataway, NJ).

Cell Cultures and Inhibitor Treatment

Human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells were maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen) and grown at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. To explore the function of Hsp90 in the system, HEK293T or HT1080 cells were treated with GA, a specific inhibitor of Hsp90 function, at a final concentration of 1.5 μM for the indicated amounts of time.

Transfection and Generation of a Stable Cell Line Expressing FLAG-tagged rpS3

HEK293T cells were transfected with a variety of plasmids using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The expression of appropriate proteins was confirmed by Western blotting. The HT1080 cell line, which stably expressed FLAG-tagged rpS3, was generated using Lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen). The pcDNA3-FLAG-rpS3 plasmid was transfected into HT1080 cells; clones were selected in DMEM with 5% FBS and 600 μg/ml G418 (Calbiochem; 345810). Individual clones were maintained in the same medium, which contained 40 μg/ml G418.

In Vitro Pulldown Assay Using Glutathione-S-Transferase

The complete coding region of rpS3 was inserted into pGEX-5X-1 (Amersham Bioscience). For the glutathione-S-transferase (GST) pulldown assay, full-length rpS3 fused to GST (GST-rpS3) or GST alone was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21, which was then purified on glutathione (GSH)-Sepharose 4B beads (Amersham Pharmacia). HEK293T cells in 60-mm dishes (5 × 106 cells/dish) were transfected with GFP-tagged Hsp90 using Lipofectamine. At 24 h posttransfection, cells were rinsed three times with 1 ml of ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and sonicated in 1 ml lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, and 1 mM Na3VO4, containing protease inhibitors). Cell lysates were spun at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to remove debris. Supernatants were incubated for 12 h at 4°C with GST or GST-rpS3 bound to beads. The beads were then washed three times in lysis buffer. Proteins were boiled in 2× SDS sample buffer, subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and blotted using anti-GFP antibody.

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were washed with cold PBS (pH 7.4) and trypsinized. Cell suspensions were sonicated on ice, and protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). Total proteins (80 μg) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (45 mA overnight). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk for 1 h at 4°C. Blots were incubated with primary antibody (1:1000 dilution) in a blocking solution for 1 h at 4°C. Membranes were rinsed twice with TBST (1% Tween-20 in Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.4) and incubated with secondary antibody conjugated to HRP (1:2000) in a blocking solution for 30 min at 4°C. The bound complex was visualized using the chemiluminescent Super Signal kit (Pierce).

Immunoprecipitation

Cells were harvested on ice in the after lysis buffer: 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, and protease inhibitors (2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A). Proteins were extracted by ultrasonication and centrifuged (16,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C); the supernatants were then collected and incubated with 2 μg of primary antibodies for 4 h at 4°C. The immunoprecipitates were harvested using protein A-Agarose beads. After extensive washing, immunoprecipitates were eluted by 5-min boiling of the beads in 2× SDS-PAGE sample buffer. The samples were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and characterized by Western blotting with appropriate antibodies.

Immunocytochemistry

293T cells were plated on poly-d-lysine-coated multiwell chamber slides (Becton Dickinson, Lincoln Park, NJ) and incubated for 1 d. The cells were then fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde in PBS, quenched with 50 mM NH4Cl in PBS, and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. Next, the cells were incubated with rabbit anti-rpS3 or mouse anti-Hsp90 antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. The Texas Red (red) goat anti-rabbit antibody and FITC (green) goat anti-mouse antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) were used for rpS3 and Hsp90, respectively. Stained cells were analyzed under a confocal microscope (Bio-Rad).

Ubiquitination Assay

Recombinant rpS3 cDNA was transfected with Lipofectamine according to the instructions of the manufacturer. After 24 h, transfected cells were supplied with fresh media containing 1.5 μM GA or 20 μM radicicol. The cells were incubated in the presence or absence of Hsp90 inhibitors for the indicated amounts of time. Cell harvesting and lysis were performed as described in immunoprecipitation method. In brief, immunoprecipitations were performed using equal amounts of whole cell extracts. Lysates (minimum of 400 μg for each condition) were incubated with 2 μg of antibodies (mouse anti-FLAG or anti-GFP), and immune complexes were bound on protein A-Sepharose beads for 6 h at 4°C with rotation. The beads were washed three times with ubiquitination buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, and 1% SDS) and bound proteins were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for Western blot analysis.

Ribosome Fractionation

For sucrose density gradient fractionation of ribosomes, cells were harvested after adding cycloheximide (100 μg/ml) to the medium for 15 min. The cells were then homogenized using 0.3% NP-40 lysis buffer containing 30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 50 μg/ml cycloheximide, 30 U/ml RNasin inhibitor, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM pepstatin, 1 mM aprotinin, and 1 mM leupeptin for 5 min at 4°C. The lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 × g at 4°C for 8 min, and the supernatants were collected and measured at OD260 to determine the RNA concentration. The lysates containing 800 μg of RNA were loaded to a 10–50% sucrose gradient solution containing 30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mM MgCl2, and 100 mM KCl. The gradients were centrifuged at 37,000 rpm for 2 h at 4°C using a Beckman SW40Ti rotor. One-hundred twenty fractions were collected from each tube, measured for absorbance at 254 nm using spectroscopy, and analyzed by Western blotting.

For the collection of ribosomal and nonribosomal fractions, the lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 × g at 4°C for 15 min in order to remove the mitochondria and cell debris. The supernatant was layered over a sucrose (20% wt/vol) cushion containing cycloheximide and centrifuged at 149,000 × g for 2 h. The pellet containing ribosomes and the upper and lower pellets of the nonribosomal supernatants were collected. The ribosomal pellets were resuspended in the lysis buffer, after which immunoblotting was performed.

Purification of Nucleoli

Nucleoli were isolated from 293T cells according to the method of Padilla et al. (2004), with slight modifications. 293T cells were harvested and washed three times with 1 ml of ice-cold PBS, suspended in 20 ml of RSB buffer (10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5/10 mM NaCl/1.5 mM MgCl2), incubated on ice for 30 min, and centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min at 4°C. Cells were suspended in 0.6 ml of RSB buffer containing 0.5% (wt/vol) NP-40 (IGEPAL CA-630, Sigma) and were then homogenized (Fisher Scientific, Springfield, NJ; 10 strokes with a tight pestle). The homogenate was centrifuged at 1200 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and the nuclear pellet (dispersed in 10 volumes of 0.25 M sucrose containing 3.3 mM CaCl2) was layered over 1 ml of 0.88 M sucrose. After centrifugation at 1200 × g for 10 min at 4°C, the pelleted nuclei were dispersed in 10 volumes of 0.34 M sucrose and sonified. Sonified nuclei were layered over 1 ml of 0.88 M sucrose and centrifuged at 2000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The nucleolar pellet was washed twice with 0.34 M sucrose and was stored at -80°C in 0.1 ml of the same solution. Proteins from each fraction were separated by SDS-PAGE in 10% gels, transferred to nitrocellulose, reacted with the indicated antibodies, and detected using chemiluminescence.

Metabolic Labeling

Subconfluent monolayers of HEK293T cells were treated with GA for 12 h in complete media and starved in methionine-free DMEM for 1 h before labeling with the 40 μCi/ml [35S]methionine/cysteine mixture for several minutes. To measure the translation activity of the ribosomes, labeled cells were harvested and lysed. Equal amounts of proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE in 10% gels. After the gel was dried, labeled proteins were visualized with a BAS2500 imaging analyzer (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).

RESULTS

RpS3 Specifically Interacts with Hsp90 via Both the N- and C-Termini

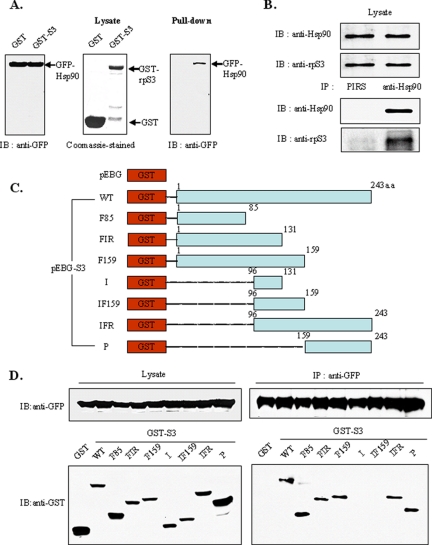

To understand how cells regulate multifunctional ribosomal protein S3, we performed a yeast two-hybrid screening of a human HeLa cell cDNA library with the full-length human rpS3 as bait to search for binding proteins. Among the numerous positive clones, Hsp90 was one of the most strongly interacting candidates. To confirm interaction, we performed a GST pulldown assay using the purified GST-tagged rpS3 protein to pull down GFP-tagged Hsp90 in HEK293T cells (Figure 1A). The GST-tagged rpS3 was immobilized to GST beads and incubated with lysates of HEK293T cells that contain GFP-tagged Hsp90. The eluted proteins were subjected to immunoblot analysis using anti-GFP antibody (Figure 1A, right panel). The results of immunoblotting revealed that GFP-Hsp90 was specifically precipitated by immobilized GST-rpS3, indicating that Hsp90 directly interacts with rpS3 in vitro. Furthermore, the endogenous rpS3 and Hsp90 proteins were specifically coimmunoprecipitated by anti-Hsp90 antibodies (Figure 1B). We also determined that ectopically expressed GFP-Hsp90 interacts with GST-rpS3 in vivo by immunoprecipitation (Figure 1D). Additionally, as shown in Figure 2D, immunostaining showed that both endogenous rpS3 and Hsp90 were mainly localized in the cytoplasm.

Figure 1.

Hsp90 interacts with rpS3 in vitro and in vivo. (A) GFP-Hsp90 fusion protein was expressed in transfected HEK293T cells. The cell lysates were then immunoblotted. GST-rpS3 fusion protein was expressed in E. coli, purified on glutathione (GSH)-Sepharose 4B beads and stained with Coomassie Blue to demonstrate the expression of the fusion proteins (A, left panels). The HEK293T cell extracts were subsequently incubated with bead-bound GST-rpS3. After the beads were washed, proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Bound GFP-Hsp90 was detected by immunoblotting with anti-GFP antibodies (A, right panel). (B) The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Hsp90 antibody, and the precipitates were immunoblotted with anti-Hsp90 and anti-rpS3 antibodies. PIRS stands for preimmune rabbit serum, used as a negative control. (C) Deletion constructs of GFP-rpS3. (D) GST-rpS3 derivatives were tested for interaction with GFP-Hsp90. GST-rpS3 and GFP-Hsp90 constructs were cotransfected into HEK293T cells. The expression levels of GST-rpS3 and GFP-Hsp90 were assessed by immunoblot analysis (D, left panel). The lysates were incubated with polyclonal anti-GST antibody, immunoprecipitated with anti-IgA-Sepharose, and subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE (D, right panel).

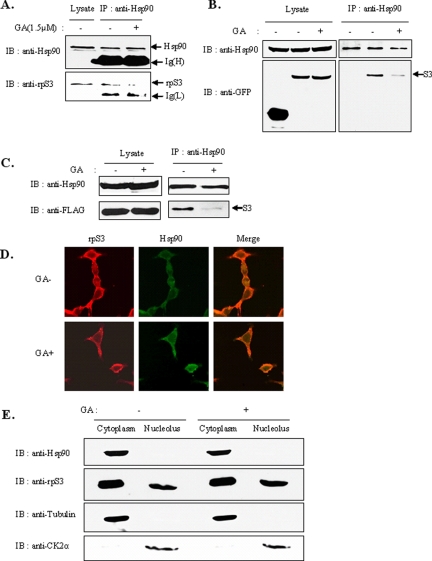

Figure 2.

Hsp90 inhibitors decrease the association between rpS3 and Hsp90. (A) HEK293T cells were treated with 1.5 μM GA for 4 h. Total cell extracts were prepared and immunoprecipitated with anti-Hsp90 antibody, and the precipitate was monitored for the presence of Hsp90 or rpS3 by immunoblotting with anti-Hsp90 or anti-rpS3. (B and C) HEK293T cells were transfected with GFP-tagged (B) or FLAG-tagged (C) rpS3. After 24 h, cells were incubated for 4 h in the absence or presence of GA (1.5 μM). The cells were then harvested and lysed. Total cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Hsp90 polyclonal antibody. The immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Coimmunoprecipitates were blotted using anti-GFP (B) or anti-FLAG (C) antibodies. (D) Subcellular localization of rpS3 and Hsp90 in 293T cells. 293T cells were treated with GA for 4 h, fixed with paraformaldehyde, and immunostained with both polyclonal anti-rpS3 (red) and monoclonal anti-Hsp90 (green) antibodies. Cells were detected by confocal microscopy. (E) HEK293T cells were incubated in the presence or absence of GA for 4 h. Total cell lysates were fractionated to isolate the nucleoli, as described in Materials and Methods. Fractionated proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-rpS3 or anti-Hsp90. The fraction marker used tubulin (cytoplasm) and CK2α (nucleolus) antibodies.

Next, to determine which region of rpS3 is involved in Hsp90 interaction, we constructed various GST-rpS3 deletion mutants (Figure 1C) and cotransfected them with GFP-Hsp90 into HEK293T cells. After 24 h, whole-cell lysates were prepared and subjected to coimmunoprecipitation with anti-GFP antibodies, followed by immunoblot analysis using anti-GFP or anti-GST antibodies (Figure 1D). The results of this analysis revealed that Hsp90 interacts with the N- (Figure 1D, bottom panel, lanes 3–5) and C- (lanes 8 and 9) termini of rpS3, but does not interact with the middle regions (lanes 6 and 7). These findings indicate that both of the termini of rpS3 were involved in the association with Hsp90. Therefore, we conclude that Hsp90 physically binds to the N- or C-terminal region of rpS3.

Geldanamycin Affects the Interaction of rpS3 with Hsp90 in the Cytosol

In our search for the biological function of rpS3-Hsp90 interaction, we investigated the interaction of two proteins in the presence of a Hsp90 inhibitor, GA, which blocks the association of Hsp90 with its substrates. Treatment with GA caused a decrease in the interaction of the two proteins (Figure 2A), which indicates that rpS3 is a client protein for active Hsp90. These results also showed the same effect in ectopically expressed rpS3 as in endogenous rpS3 (Figure 2, B and C). However, cellular distribution of the two proteins was not affected by GA (Figure 2D), which indicates that the activity of Hsp90 and its interaction with rpS3 are not correlated with the localization of both proteins. Taken together, the association of rpS3 with Hsp90 was inhibited by GA treatment, as in other Hsp90 substrates, but did not affect their cellular distribution. Previous studies reported that Hsp90 was mainly localized in the cytoplasm, with only minor amounts inside the nuclei. Hsp90, however, could not be detected inside the nucleoli (Langer et al., 2003). To confirm where the interaction between Hsp90 and rpS3 occurred, HEK293T cells were incubated in the presence or absence of GA for 4 h and separated into the cytoplasm and nucleolus fractions by differential centrifugation. This process revealed that Hsp90 was localized in the cytoplasm, whereas rpS3 was localized in both the cytoplasm and the nucleolus (Figure 2E). Additionally, the localization of Hsp90 was not changed in cells treated with GA, which means that Hsp90 function is restricted to the cytosol.

GA Affects the Protein Stability of rpS3

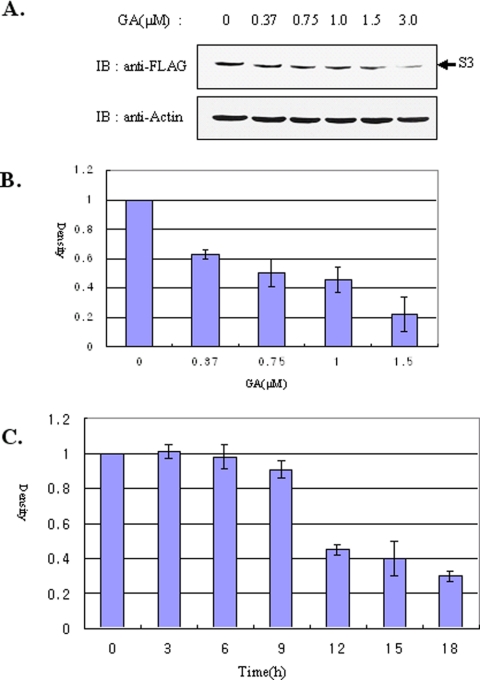

GA binds to the amino-terminal ATP-binding domain of Hsp90 and blocks the activity of this protein within the cell (Roe et al., 1999; Marcu et al., 2000), thereby leading to the dissociation and eventual degradation of Hsp90-interacting proteins (Pratt, 1998; Blagosklonny, 2002). In the preceding section, we showed that GA induces the dissociation of rpS3 from Hsp90. Because there is a possibility that dissociated substrates might be destabilized, we examined whether the stability of rpS3 is dependent on Hsp90-binding. Therefore, we treated HT1080 cells which stably expressed FLAG-tagged rpS3 (Figure 3A) and HEK293T (Figure 3B) cells with increasing concentrations of GA in order to assess the levels of endogenous rpS3. As shown in Figure 3, A and B, GA treatment caused a marked decrease in the levels of exogenous (Figure 3A) and endogenous rpS3 (Figure 3B) proteins. To validate these results, we investigated whether the levels of endogenous rpS3 were decreased in a time-dependent manner. As shown in Figure 3C, the level of endogenous rpS3 decreased after 9 h upon treatment with GA in HEK293T cells. Taken together, these results indicate that the molecular chaperoning activity of Hsp90, an ATPase activity, appears to play an important role in the rpS3 stability in cells.

Figure 3.

RpS3 was degraded by Hsp90 inhibitors. (A) HT1080 cells stably expressing the wild-type rpS3 tagged with FLAG were treated with different concentrations of GA for 16 h. To measure the FLAG-rpS3 levels, total cell lysates were blotted using anti-FLAG and anti-actin antibodies. (B) To measure the levels of endogenous rpS3 protein, HEK293T cells were incubated with different concentrations of GA for 20 h. Total cell lysates were blotted using anti-rpS3 and anti-actin antibodies. (C) To measure the endogenous rpS3 protein levels, HEK293T cells were treated with GA (1.5 μM) in a time-dependent manner. Each lane of SDS-PAGE contains 80 μg of total lysates. Error bars represent SDs from the mean of at least three independent experiments.

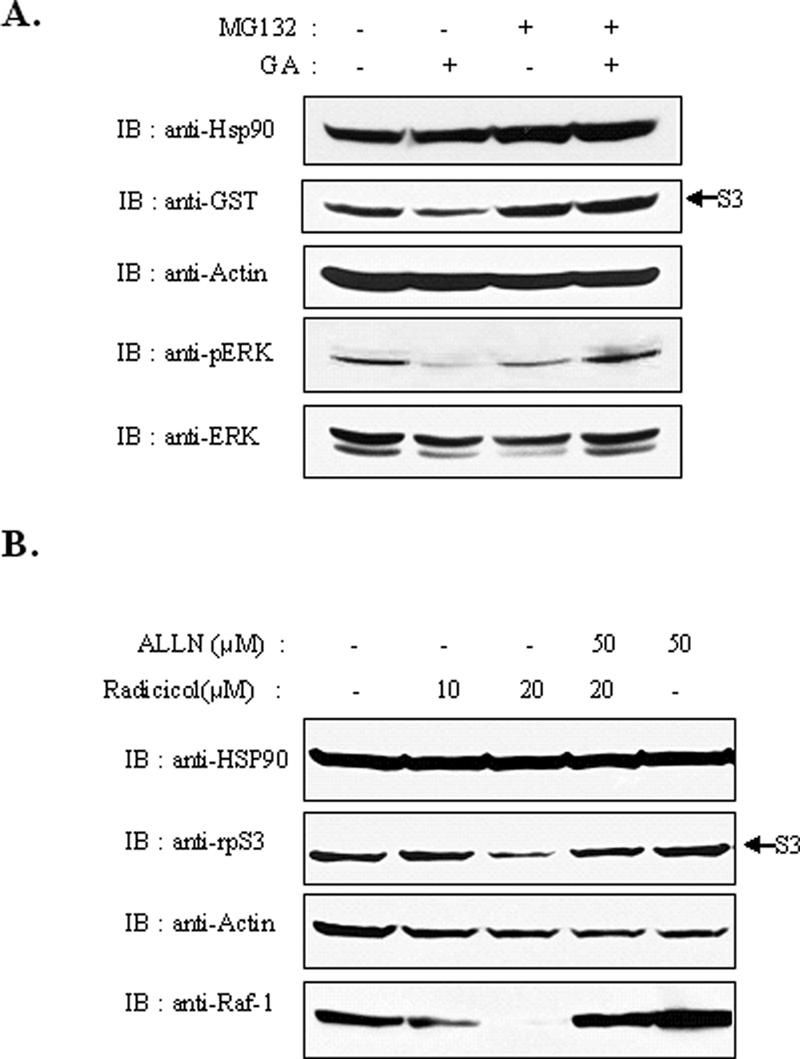

Hsp90-induced rpS3 Degradation Is Proteasome-dependent

Protein degradation in cells can be achieved by several protease systems; however, most proteins, the stability of which is regulated by Hsp90, appear to be degraded by proteasomes. To investigate whether the reduction of rpS3 was due to proteasomal degradation, we treated HEK293T cells with proteasome inhibitors, MG132 or ALLN, to prevent the GA-induced degradation of exogenous or endogenous rpS3. The results of this treatment revealed that GA-induced rpS3 degradation can be blocked by proteasome inhibitors (Figure 4A). In cells treated with MG-132, the rpS3 protein level appears slightly increased. Moreover, the levels of endogenous rpS3 were decreased in a dose-dependent manner, but recovered in the ALLN-treated cells (Figure 4B). Raf-1 and phospho-Erk were used to verify the effects of the Hsp90 inhibitors, GA and radicicol. From these results, we noticed that proteasome inhibitors substantially prevented the degradation of rpS3 in cells treated with GA or radicicol. This is probably due to the fact that the dysfunction of Hsp90 by treatment with Hsp90 inhibitors destabilized the rpS3 protein. Therefore, it is clear that proteasome-dependent degradation causes the decreased level of rpS3 protein. This indicates that the stability of rpS3 was supported by Hsp90 and that unstable rpS3 was removed by proteasomes.

Figure 4.

Reduction of rpS3 was prevented by proteasome inhibitor treatment. (A) HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with GST-rpS3. After 24 h, cells were treated with GA (1.5 μM) after pretreatment with 20 μM of proteasome inhibitor MG-132 for 2 h. Cell lysates were prepared and resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE. Phospho-ERK was used to verify the effect of GA treatment. (B) HEK293T cells were treated with ALLN proteasome inhibitor, followed by treatment with radicicol. Cells were harvested and immunoblotted. Raf-1 was used to verify the effect of ALLN.

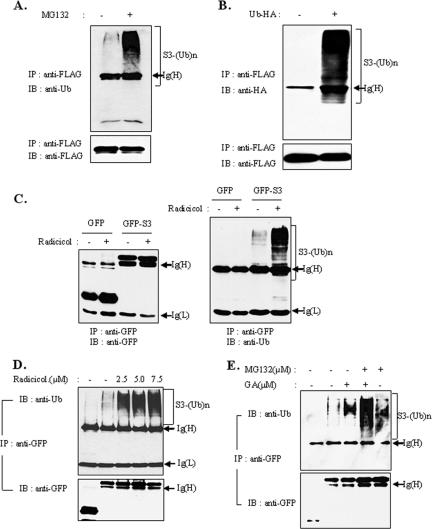

Ubiquitination of rpS3 In Vivo

Ubiquitin conjugation is a common mechanism of the proteasome-dependent degradation process. Thus, we suspected that the degradation of rpS3 protein is related to conjugation with ubiquitin. To test the ubiquitination of rpS3, HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with FLAG-tagged rpS3 and treated with 20 μM MG-132 or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as a control after 24 h. Notable accumulation of poly-ubiquitinated forms of FLAG-tagged rpS3 were observed in the presence of proteasome inhibitors. This was performed by coimmunoprecipitation assay with an anti-FLAG antibody, followed by an immunoblot assay (Figure 5A). Coimmunoprecipitation studies using transiently transfected HEK293T cells with HA-tagged ubiquitin and FLAG-tagged rpS3 were used to confirm the ubiquitination of rpS3. As shown in Figure 5B, FLAG-tagged rpS3 was significantly conjugated with HA-tagged ubiquitin only in cells cotransfected with HA-tagged ubiquitin (lane 2). Next, we investigated whether the ubiquitination of rpS3 was affected by Hsp90 inhibitors. For this, we transfected GFP-rpS3 into 293T cells, treated cells with radicicol, and performed coimmunoprecipitation with an anti-GFP antibody. Notably, polyubiquitinated rpS3 was detected at a higher level in cells treated with radicicol than in cells treated only with DMSO (Figure 5C); the quantity of polyubiquitinated rpS3 increased in proportion to the radicicol concentration (Figure 5D). In addition to this, the amounts of ubiquitin-conjugated forms of rpS3 proteins were accumulated at higher levels in cells treated with both proteasome inhibitors and Hsp90 inhibitors than in cells treated with only one kind of inhibitor (Figure 5E). Overall, these results suggest that destabilized rpS3 protein is degraded by proteasome-dependent proteolysis mediated by ubiquitin conjugation, and Hsp90 plays an important role in maintaining the stable form of rpS3 protein in vivo.

Figure 5.

RpS3 degradation is mediated through the ubiquitin-dependent proteasome pathway. (A) HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with FLAG-rpS3. After 24 h, cells were treated with 20 μM of MG-132 for 4 h. Cells were harvested, lysed, and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (mAb). Immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies. (B) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with FLAG-rpS3 and HA-tagged ubiquitin and were harvested after 24-h incubation. The lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG mAb. Ubiquitin-conjugated rpS3 was detected by immunoblotting. (C) HEK293T cells were transfected with GFP-rpS3. After 24 h, cells were treated with 20 μM of radicicol for 16 h. Recombinant proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-GFP antibody and were then resolved by PAGE (left panel). The levels of ubiquitinated rpS3 were determined by Western blot analysis (right panel). The two left lanes of the gels are for GFP controls, and the two right lanes of the gels are for GFP-S3. (D) HEK293T cells were transfected with pEGFPc1-rpS3 to express GFP-rpS3. After 24 h, transfected cells were incubated with 0, 2.5, 5.0, and 7.5 μM of radicicol for 16 h. GFP-rpS3 was immunoprecipitated with anti-GFP mAb, and polyubiquitinated rpS3 was detected using anti-ubiquitin mAb. (E) HEK293T cells were transfected with GFP-tagged rpS3. After 24 h, transfected cells were pretreated with 20 μM of MG-132 (lanes 4 and 5) for 2 h and were then treated with 1.5 μM of GA (lanes 3 and 4) for 6 h. The GFP-rpS3 protein immunoprecipitated with anti-GFP antibodies was separately detected using anti-GFP and anti-ubiquitin monoclonal antibodies.

Hsp70 Facilitates rpS3 Transfer for Degradation

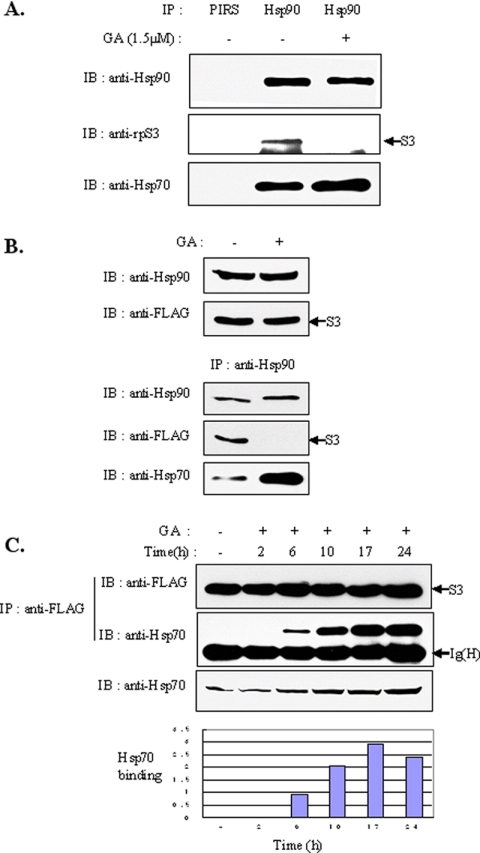

Ubiquitin-dependent proteasomal degradation of several Hsp90-client proteins has appeared to be related with Hsp70 in a manner that is independent from their biological functions (Gusarova et al., 2001; Hohfeld et al., 2001). The client proteins of Hsp90 appear to shift the role of primary chaperone from Hsp90 to Hsp70 in cells treated with Hsp90 inhibitors (Doong et al., 2003). It is also well known that GA caused a modest increase in Hsp70 levels (Lawson et al., 1998). To test whether Hsp70 is involved in rpS3 ubiquitination, HEK293T cells were treated with GA for 4 h, after which the interactions between endogenous rpS3, Hsp90, and Hsp70 were investigated. As expected, significant induction of Hsp70 was detected in our experiment. Although the interaction between rpS3 and Hsp90 was interrupted by an Hsp90 inhibitor, the interaction between Hsp90 and Hsp70 was strengthened (Figure 6A). The same effect was shown in the HT1080 cells transfected with FLAG-tagged rpS3 (Figure 6B). In connection with Figure 6, A and B, we investigated whether treatment with an Hsp90 inhibitor also induces the association between rpS3 and Hsp70 (Figure 6C). Remarkably, GA treatment to HT1080 cells transfected with FLAG-tagged rpS3 increased the association of Hsp70 with rpS3 (Figure 6C). Although GA treatment induced Hsp70 expression, the affinity between rpS3 and Hsp70 was increased much more. These results suggest that Hsp70 is involved in the rpS3 degradation mechanism in case of Hsp90 dysfunction.

Figure 6.

Hsp90 inhibitors induce the association of rpS3 with Hsp70. (A) HEK293T cells were treated with GA for 4 h. Total cell extracts were prepared and immunoprecipitated with anti-Hsp90 antibody, and the precipitate was then monitored for the presence of Hsp90 or rpS3 by immunoblotting with anti-Hsp90 or anti-rpS3. PIRS was used as a negative control. (B) HT1080 cells stably expressing FLAG-rpS3 were treated with 1.5 μM of GA for 4 h, and total cell lysates were then immunoprecipitated with anti-Hsp90 antibody. The precipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred, and immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies. (C) HT1080 cells stably expressing FLAG-tagged rpS3 were incubated with 1.5 μM of GA for the indicated amounts of time. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG mAb. The precipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and detected by immunoblot analysis using anti-Hsp70 antibody. The graph was normalized by dividing the value of the binding result by the value of the lysate and expressed as fold increase.

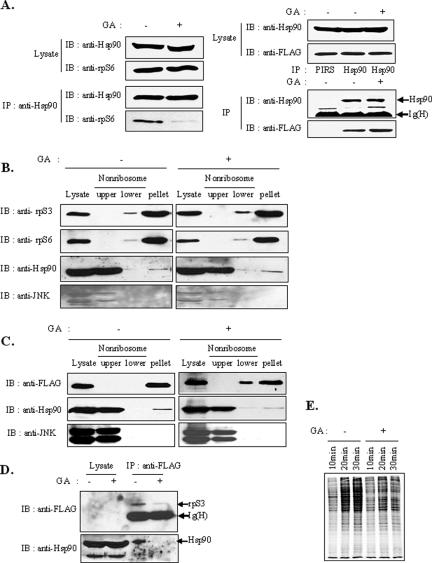

Hsp90 Dysfunction Affects the Stability of Free Ribosomal Proteins and the State of Ribosome

The results mentioned above led us to hypothesize that the interaction and regulation by Hsp90 might be associated not only with rpS3, but also with other ribosomal proteins in the 40S subunit. To confirm this assumption, we performed an immunoprecipitation assay between other ribosomal proteins and Hsp90 in the presence or absence of GA treatment. Notably, endogenous rpS6 was also coimmunoprecipitated with endogenous Hsp90. This interaction was also disrupted by GA treatment (Figure 7A, top panel). On the other hand, the interaction of another ribosomal protein, rpS11, with Hsp90 was not affected by GA treatment (Figure 7A, bottom panel), which suggests that rpS11 is not a client protein of Hsp90. These results show that Hsp90 partly modulates the stability of ribosomal proteins in the 40S subunit. The finding that the stability of ribosomal proteins was regulated by a functional Hsp90 suggests that Hsp90 might play a role in monitoring the functions of ribosomes. To demonstrate the physiological relevance of Hsp90 and the functions of rpS3 and ribosomes, we fractionated soluble ribosomal proteins from ribosomal monosomes and polysomes in normal and GA-treated HT1080 cells. Cell lysates were fractionated on a 10–50% sucrose gradient, and the positions of ribosomal subunits (40S, 60S), ribosomal monomers (80S), polysomes, and free ribosomal proteins in the fractions were measured. Fractions were collected and subjected to immunoblot assay for the detection of rpS3, rpS6, and Hsp90. Although Hsp90 was coeluted with the 40S subunit, mostly with free ribosomal proteins (Supplementary Figure S1A), treatment with GA caused a remarkable decrease in free rpS3 and rpS6, but not those in monosomes and polysomes (Supplementary Figure S1B). This indicates that Hsp90 stabilizes the free form of ribosomal proteins, but does not stabilize the proteins in monosomes and polysomes. However, in GA-treated cells, the peaks of the monosomes, especially those of the 80S and 40S subunits, were broader and lower than those in normal cells, which suggests that Hsp90 also influences the state of the 40S subunit.

Figure 7.

Hsp90 inhibition affects the state of ribosomes. (A) HEK293T cells were treated with 1.5 μM of GA for 4 h. Total cell extracts were prepared and immunoprecipitated with anti-Hsp90 antibody, and the precipitate was then monitored for the presence of Hsp90 or rpS6 by immunoblotting with anti-Hsp90 or anti-rpS6 (top panel). HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged rpS11. After 24 h, cells were treated with 1.5 μM GA for 4 h. Total cell extracts were prepared and immunoprecipitated with anti-Hsp90 or control antibodies (bottom panel). (B) The 40S ribosomal subunit is influenced by GA. HT1080 cells were treated with GA for 4 h. Cell extracts from control or GA-treated HT1080 cells were centrifuged at low speed. Ribosomes were precipitated by ultracentrifugation at 150,000 × g for 2 h through a sucrose cushion. Ribosomal (pellet) and nonribosomal (upper and lower) fractions were subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-rpS3, anti-rpS6, anti-Hsp90, or anti-JNK antibodies. (C) Stably expressed FLAG-rpS3 showed a similar result as with endogenous rpS3. Cell extracts from FLAG-rpS3-expressing HT1080 cells were ultracentrifuged at 150,000 × g for 2 h through a sucrose cushion. Ribosomal (pellet) and nonribosomal (upper and lower) fractions were subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-FLAG, anti-Hsp90, or anti-JNK antibodies. (D) Hsp90 interacts with free rpS3 and protects from degradation. The upper fraction of (C) was used for immunoprecipitation with the anti-FLAG antibody, followed by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG or anti-Hsp90 antibodies. (E) HEK293T cells were left untreated or treated with 1.5 μM of GA for 12 h and subjected to [35S]-metabolic labeling for 10, 20, and 30 min. Equal amounts of proteins were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and analyzed by autoradiography.

To further examine the effect of GA on the ribosomes, HT1080 cells were incubated with GA for 4 h, and lysates were fractionated on a sucrose cushion to separate the ribosomal fraction from the nonribosomal fraction. Fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis with anti-rpS3 or anti-rpS6 antibodies. Consistent with the result shown in Supplementary Figure S1A, small amount of endogenous Hsp90 proteins were associated with ribosomes (Figure 7B). As expected, rpS3 was mainly found in the ribosomal fraction, and 7.4% of rpS3 was found in the nonribosomal lower fraction with high-molecular-weight proteins. However, the rpS3 level in the lower fraction increased more than twofold (15.4%), but this increase was not observed in the upper, low-molecular-weight fraction 4 h after treatment with GA (Figure 7B). This finding indicates that GA affected the state of the ribosome. However, rpS3 and rpS6 were not detected in the nonribosomal upper fraction. To confirm whether rpS3 was present and influenced by GA in the upper fraction, we performed an immunoprecipitation assay with the upper fraction in FLAG-rpS3-expressing cells. Exogenous FLAG-tagged rpS3 was affected by GA in the same manner as with endogenous rpS3 (Figure 7C). As shown in a representative result in Figure 7D, a small amount of rpS3 was present, interacted with Hsp90, and decreased by GA in the upper fraction, indicating that Hsp90 protects the degradation of free rpS3.

It was reported that GA interferes with this chaperone's role of GRP94, which is a Hsp90 paralog located in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), in protein maturation and also induces the concomitant transience of unfolded protein response (UPR; Lawson et al., 1998; Marcu et al., 2002). However, this UPR is eventually superseded by Hsp90-dependent destabilization of unfolded protein response signaling including ER-resident transmembrane protein kinases such as IRE1α and PERK. These kinases are known as a client protein of Hsp90. While GA itself causes a noticeable but transient attenuation of translation in early time, this translational attenuation is overcome within 2 h after GA treatment. Interestingly, a slow decline of protein synthesis is shown in late time when GA-induced UPR is terminated. To verify whether prolonged exposure to GA affects the ribosomal translation activity, we performed metabolic labeling. HEK293T cells were treated with GA for 12 h and were grown several times in the presence of 35S. Metabolically labeled proteins were quantified using the Bradford assay, and equal amounts of proteins were detected by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. As shown in Figure 7E, ribosomal translation efficiency was decreased in cells treated with GA. These results show that Hsp90 greatly influences ribosome biogenesis and translation activity independently of UPR. Therefore, we concluded that Hsp90 interacts with ribosomal proteins to regulate its stability and translational activity.

DISCUSSION

Hsp90 is an abundant, highly conserved protein that is involved in a variety of cellular processes. In contrast to other heat-shock proteins, Hsp90 is not involved in the maturation or maintenance of most proteins in vivo. Instead, Hsp90 stabilizes the client proteins and protects against ubiquitin-dependent proteasomal degradation through its interactions with many signaling or enzymatic molecules. Therefore, Hsp90 plays an important role in the maintenance of protein quality by regulating the balance between the folding and degradation of proteins.

Hsp90 contains a highly conserved ATP-binding pocket in an NH2-terminal domain that is required for its function (Obermann et al., 1998). Several natural products, including ansamycin antibiotics such as GA, bind to this pocket and inhibit the function of Hsp90 (Stebbins et al., 1997). These drugs induce the degradation of the client proteins of Hsp90, such as Raf (Schulte et al., 1995) and HER2 (Chiosis et al., 2001), and have been used as probes for the biochemical and cellular functions of this chaperone. In this report, we showed that the rpS3 and rpS6 protein levels were decreased in cells treated with Hsp90 inhibitors. This is also true in the cases of Lck (Giannini and Bijlmakers, 2004) and Raf-1 (Schulte et al., 1995).

It has been reported that, in prokaryotes, chaperones play important, direct roles in ribosome biogenesis (Maki et al., 2002). However, not much information has been revealed regarding their roles in eukaryotes. In this article, we were the first to show several lines of evidence to confirm that Hsp90 also plays important roles in the activities of the ribosome in eukaryotes. First, Hsp90 is cosedimented with a 40S ribosomal subunit by sucrose gradient sedimentation centrifugation (Supplementary Figure S1A). Although the mechanism of regulation for protein synthesis remains to be elucidated, the interaction of 40S-Hsp90 appears to influence the functions of ribosomes (Figure 7). Second, Hsp90 inhibitors influence the protein synthesis of ribosomes without decreasing the total amount of ribosomal proteins during early periods of protein synthesis (Supplementary Figure S1B). In contrast, the total amount of ribosomal proteins decreases during a later time upon treatment with Hsp90 inhibitors (Figure 5A), which implies that the stability of ribosomal proteins in ribosomes is also regulated by Hsp90.

Our study indicates that Hsp90 chaperones free forms of 40S ribosomal proteins, such as rpS3 and rpS6, via physical interaction. Consequently, Hsp90 also coordinates the optimal state of ribosomal function. The ribosome is the cellular machinery for protein synthesis and is composed of ribosomal proteins and ribosomal RNAs. Most of the cellular energy that the ribosome consumes is used for the construction of cellular ribosomes when cells are growing actively. Therefore, ribosome biogenesis should be a highly complex, coordinated process (Leary and Huang, 2001; Fromont-Racine et al., 2003). Hsp90 appears to be necessary to guard the free forms of ribosomal proteins against voluntary mismanagement and destruction in the initial step of ribosome assembly. Unlike the free form of ribosomal proteins, which appears to be important as an initial step in ribosome biogenesis but is unstable alone, the ribosomal proteins in the ribosome, including 40S, 60S, 80S, and polysomes, appear to be stable for some time under treatment with Hsp90 inhibitors (Supplementary Figure S1B). However, we showed that the pattern of ribosome composition was disrupted by treatment with Hsp90 inhibitor (Figure 7), indicating that the activity of the ribosome itself is also regulated by Hsp90. Moreover, the interaction between rpS11 and Hsp90 was not influenced by Hsp90 inhibitors, which suggests that further exploration is needed to determine how ribosomes are regulated by Hsp90 and how many ribosomal proteins are regulated by Hsp90.

Our results also showed that rpS3 degradation is mediated by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. This process is related to the operation of a molecular chaperone called Hsp70 because GA treatment increases the dissociation of rpS3 from Hsp90, while increasing its association with Hsp70 (Figure 6). This phenomenon appears to occur before the degradation of rpS3 protein, as shown in the case of ErbB2 (Xu et al., 2001). The relationship between Hsp70 and the proteasome is not well understood, but we can postulate why this phenomenon occurs using the following explanations. First, Hsp70 is recruited to the substrate-Hsp90 complex because of the destabilized substrate, and polyubiquitination is then carried out in the heterocomplex. Second, a substrate that first bound to Hsp90 is then transferred to Hsp70, and the dissociated substrate is then poly-ubiquitinated by a ubiquitin-ligating enzyme. However, it remains to be elucidated which E3 ubiquitin ligase is involved in rpS3 ubiquitination at this time.

In the case of rpS3 degradation, the conjugation of ubiquitin to the rpS3 protein may play an important role in maintaining the appropriate levels of functional rpS3 proteins in vivo. From this point of view, it is conceivable that ribosomal proteins are quantitatively monitored by Hsp90 and qualitatively monitored by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Additionally, it should be noted that rpS3 plays multiple roles in cells. It is a component of the 40S ribosomal subunit for protein synthesis under favorable growth conditions, as well as a DNA repair enzyme with endonuclease activity on DNAs with incurring damage as a result of UV irradiation, AP sites, and others (Kim et al., 1995). It is also involved in apoptosis in certain cells (Jang et al., 2004). Therefore, in order to play their versatile roles, rpS3 proteins might require a check and balance in maintaining its stability through Hsp90 and ubiquitination. However, it is a subject of future investigation whether the rpS3 proteins engaged in ribosomes could appear at any point, as with rpL11 (Zhang et al., 2003) or whether only free rpS3 proteins are subject to extraribosomal functions.

In this report, we confirmed that the levels of 40S ribosomal proteins, including rpS3 and rpS6, were decreased by treatment with Hsp90 inhibitors in conjunction with ubiquitination. The interaction between 40S ribosomal proteins and Hsp90 was also associated with ribosomal activities, such as protein synthesis. Further studies of the relationship between ribosomal proteins and Hsp90 could help lead us to a better understanding of how many ribosomal proteins are controlled by chaperones, and how the ribosome and ribosome biogenesis are modulated by chaperones in cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the FPR05C2–390 Grant from the Korean Ministry of Science and Technology.

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E05–08–0713) on November 28, 2005.

Abbreviations used: rpS3, ribosomal protein S3; Hsp90, heat-shock protein 90; GA, geldanamycin.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

References

- Blagosklonny, M. V. (2002). Hsp-90-associated oncoproteins: multiple targets of geldanamycin and its analogs. Leukemia 16, 455-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiosis, G., Timaul, M. N., Lucas, B., Munster, P. N., Zheng, F. F., Sepp-Lorenzino, L., and Rosen, N. (2001). A small molecule designed to bind to the adenine nucleotide pocket of Hsp90 causes Her2 degradation and the growth arrest and differentiation of breast cancer cells. Chem. Biol. 8, 289-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell, P., Ballinger, C. A., Jiang, J., Wu, Y., Thompson, L. J., Hohfeld, J., and Patterson, C. (2001). The co-chaperone CHIP regulates protein triage decisions mediated by heat-shock proteins. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 93-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coumailleau, P., Poellinger, L., Gustafsson, J. A., and Whitelaw, M. L. (1995). Definition of a minimal domain of the dioxin receptor that is associated with Hsp90 and maintains wild type ligand binding affinity and specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 25291-25300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doong, H., Rizzo, K., Fang, S., Kulpa, V., Weissman, A. M., and Kohn, E. C. (2003). CAIR-1/BAG-3 abrogates heat shock protein-70 chaperone complex-mediated protein degradation: accumulation of poly-ubiquitinated Hsp90 client proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 28490-28500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromont-Racine, M., Senger, B., Saveanu, C., and Fasiolo, F. (2003). Ribosome assembly in eukaryotes. Gene 313, 17-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Cardena, G., Fan, R., Shah, V., Sorrentino, R., Cirino, G., Papapetropoulos, A., and Sessa, W. C. (1998). Dynamic activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by Hsp90. Nature 392, 821-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannini, A., and Bijlmakers, M. J. (2004). Regulation of the Src family kinase Lck by Hsp90 and ubiquitination. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 5667-5676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusarova, V., Caplan, A. J., Brodsky, J. L., and Fisher, E. A. (2001). Apoprotein B degradation is promoted by the molecular chaperones hsp90 and hsp70. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 24891-24900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohfeld, J., Cyr, D. M., and Patterson, C. (2001). From the cradle to the grave: molecular chaperones that may choose between folding and degradation. EMBO Rep. 2, 885-890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt, S. E. et al. (1999). Functional requirement of p23 and Hsp90 in telomerase complexes. Genes Dev. 13, 817-826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang, C. Y., Lee, J. Y., and Kim, J. (2004). RpS3, a DNA repair endonuclease and ribosomal protein, is involved in apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 560, 81-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H. D., Lee, J. Y., and Kim, J. (2005). Erk phosphorylates threonine 42 residue of ribosomal protein S3. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 333, 110-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J., Chubatsu, L. S., Admon, A., Stahl, J., Fellous, R., and Linn, S. (1995). Implication of mammalian ribosomal protein S3 in the processing of DNA damage. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 13620-13629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. H., Lee, J. Y., and Kim, J. (2005). Characterization of a wide range base-damage-endonuclease activity of mammalian rpS3. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 328, 962-967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary, D. J., and Huang, S. (2001). Regulation of ribosome biogenesis within the nucleolus. FEBS Lett. 509, 145-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer, T., Rosmus, S., and Fasold, H. (2003). Intracellular localization of the 90 kDA heat shock protein (HSP90alpha) determined by expression of a EGFP-HSP90alpha-fusion protein in unstressed and heat stressed 3T3 cells. Cell Biol. Int. 27, 47-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, B., Brewer, J. W., and Hendershot, L. M. (1998). Geldanamycin, an Hsp90/GRP94-binding drug, induces increased transcription of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) chaperones via the ER stress pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 174, 170-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. M., Kim, M., Moon, E. P., Lee, B. J., Choi, J., and Kim, J. (2006). Genomic structure and transcriptional studies on the mouse ribosomal protein S3 gene: expression of U15 small nucleolar RNA. Gene (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lim, Y., Lee, S. M., Kim, M., Lee, J. Y., Moon, E. P., Lee, B. J., and Kim, J. (2002). Complete genomic structure of human rpS3, identification of functional U15b snoRNA in the fifth intron. Gene 286, 291-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki, J. A., Schnobrich, D. J., and Culver, G. M. (2002). The DnaK chaperone system facilitates 30S ribosomal subunit assembly. Mol. Cell 10, 129-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcu, M. G., Chadli, A., Bouhouche, I., Catelli, M., and Neckers, L. M. (2000). The heat shock protein 90 antagonist novobiocin interacts with a previously unrecognized ATP-binding domain in the carboxyl terminus of the chaperone. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 37181-37186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcu, M. G., Doyle, M., Bertolotti, A., Ron, D., Hendershot, L., and Neckers, L. (2002). Heat shock protein 90 modulates the unfolded protein response by stabilizing IRE1alpha. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 8506-8513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClellan, A. J., and Frydman, J. (2001). Molecular chaperones and the art of recognizing a lost cause. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, E51-E53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meacham, G. C., Patterson, C., Zhang, W., Younger, J. M., and Cyr, D. M. (2001). The Hsc70 co-chaperone CHIP targets immature CFTR for proteasomal degradation. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 100-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata, Y., Anan, T., Yoshida, T., Mizukami, T., Taya, Y., Fujiwara, T., Kato, H., Saya, H., and Nakao, M. (1999). The stabilization mechanism of mutant-type p53 by impaired ubiquitination: the loss of wild-type p53 function and the hsp90 association. Oncogene 18, 6037-6049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naora, H. (1999). Involvement of ribosomal proteins in regulating cell growth and apoptosis: translational modulation or recruitment for extraribosomal activity? Immunol. Cell Biol. 77, 197-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obermann, W. M., Sondermann, H., Russo, A. A., Pavletich, N. P., and Hartl, F. U. (1998). In vivo function of Hsp90 is dependent on ATP binding and ATP hydrolysis. J. Cell Biol. 143, 901-910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla, P. I., Pacheco-Rodriguez, G., Moss, J., and Vaughan, M. (2004). Nuclear localization and molecular partners of BIG1, a brefeldin A-inhibited guanine nucleotide-exchange protein for ADP-ribosylation factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 2752-2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearl, L. H., and Prodromou, C. (2001). Structure, function, and mechanism of the Hsp90 molecular chaperone. Adv. Protein Chem. 59, 157-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng, H. M., Morishima, Y., Jenkins, G. J., Dunbar, A. Y., Lau, M., Patterson, C., Pratt, W. B., and Osawa, Y. (2004). Ubiquitylation of neuronal nitric-oxide synthase by CHIP, a chaperone-dependent E3 ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 52970-52977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, W. B. (1998). The hsp90-based chaperone system: involvement in signal transduction from a variety of hormone and growth factor receptors. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 217, 420-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prodromou, C., Roe, S. M., O'Brien, R., Ladbury, J. E., Piper, P. W., and Pearl, L. H. (1997). Identification and structural characterization of the ATP/ADP-binding site in the Hsp90 molecular chaperone. Cell 90, 65-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter, K., and Buchner, J. (2001). Hsp90, chaperoning signal transduction. J. Cell. Physiol. 188, 281-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe, S. M., Prodromou, C., O'Brien, R., Ladbury, J. E., Piper, P. W., and Pearl, L. H. (1999). Structural basis for inhibition of the Hsp90 molecular chaperone by the antitumor antibiotics radicicol and geldanamycin. J. Med. Chem. 42, 260-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, E. R., Toft, D. O., Schlesinger, M. J., and Pratt, W. B. (1985). Evidence that the 90-kDa phosphoprotein associated with the untransformed L-cell glucocorticoid receptor is a murine heat shock protein. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 12398-12401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato, S., Fujita, N., and Tsuruo, T. (2000). Modulation of Akt kinase activity by binding to Hsp90. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 10832-10837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheufler, C., Brinker, A., Bourenkov, G., Pegoraro, S., Moroder, L., Bartunik, H., Hartl, F. U., and Moarefi, I. (2000). Structure of TPR domain-peptide complexes: critical elements in the assembly of the Hsp70-Hsp90 multichaperone machine. Cell 101, 199-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte, T. W., Blagosklonny, M. V., Ingui, C., and Neckers, L. (1995). Disruption of the Raf-1-Hsp90 molecular complex results in destabilization of Raf-1 and loss of Raf-1-Ras association. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 24585-24588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins, C. E., Russo, A. A., Schneider, C., Rosen, N., Hartl, F. U., and Pavletich, N. P. (1997). Crystal structure of an Hsp90-geldanamycin complex: targeting of a protein chaperone by an antitumor agent. Cell 89, 239-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan, D. R., Hershey, J. W., and Traut, R. T. (1983). Crosslinking of eukaryotic initiation factor eIF3 to the 40S ribosomal subunit from rabbit reticulocytes. Biochimie 65, 427-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermann, P., Heumann, W., Bommer, U. A., Bielka, H., Nygard, O., and Hultin, T. (1979). Crosslinking of initiation factor eIF-2 to proteins of the small subunit of rat liver ribosomes. FEBS Lett. 97, 101-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W., Mimnaugh, E., Rosser, M. F., Nicchitta, C., Marcu, M., Yarden, Y., and Neckers, L. (2001). Sensitivity of mature Erbb2 to geldanamycin is conferred by its kinase domain and is mediated by the chaperone protein Hsp90. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 3702-3708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y., Wolf, G. W., Bhat, K., Jin, A., Allio, T., Burkhart, W. A., and Xiong, Y. (2003). Ribosomal protein L11 negatively regulates oncoprotein MDM2 and mediates a p53-dependent ribosomal-stress checkpoint pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 8902-8912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, P., Fernandes, N., Dodge, I. L., Reddi, A. L., Rao, N., Safran, H., DiPetrillo, T. A., Wazer, D. E., Band, V., and Band, H. (2003). ErbB2 degradation mediated by the co-chaperone protein CHIP. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 13829-13837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, R. A. (2003). The double life of ribosomal proteins. Cell 115, 130-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.