Abstract

Upon injection of Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide into human volunteers, the monocyte density of CC chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) decreased. Minimal CCR2 density was observed 4 h after injection. Peak plasma concentrations of the CCR2 ligand monocyte chemotactic protein 1 and of tumor necrosis factor alpha were reached after 4 h and 2 h, respectively.

The CC chemokine monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1 [also known as CCL2]) triggers the migration of monocytes into injured tissue, thereby initiating a central step during infection (8). MCP-1 is protective in lethal endotoxemia, as was shown in anti-MCP-1-treated mice (15). This effect is related to an MCP-1-induced shift from proinflammatory to anti-inflammatory cytokines (6, 15). Administration of recombinant MCP-1 to mice resulted in an increase of interleukin-10 concentrations, while interleukin-12 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) levels decreased (15). In addition, MCP-1 also triggers the recruitment of neutrophils by augmenting the levels of leukotriene B4 during septic peritonitis (7).

MCP-1 binds to the G-protein-coupled receptor CC chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) (2) expressed on the cell surface of monocytes. CCR2 is not a static entity but is subjected to dynamic regulation. TNF-α induced a decrease of the monocyte surface expression of CCR2 (12). Sica et al. (10) reported that lipopolysaccharide (LPS), an outer membrane component of gram-negative bacteria, reduced monocyte CCR2 mRNA levels in vitro by decreasing the mRNA half-life (10). Knowledge of CCR2 expression on monocytes in vivo is limited. Therefore, in the present study, we sought to determine time-dependent alterations in monocyte CCR2 expression after intravenous administration of LPS to healthy humans.

Experimental human endotoxemia.

After approval by the local ethics committee and written informed consent, eight healthy men (ages 18 to 35 years) were admitted to the clinical research unit of the Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam. The volunteers were in good health as documented by medical history, physical examination, hematologic and biochemical laboratory measurements, electrocardiography, and chest radiography. Exclusion criteria were the use of any medication, smoking, and febrile illness within 2 weeks prior to the start of the study. Four nanograms of LPS per kilogram of body weight (Escherichia coli, lot G; U.S. Pharmacopeia, Rockville, MD) was injected intravenously. Venous blood samples for flow cytometry were taken prior to and 1, 2, 4, 6, and 24 h after LPS injection. These samples were processed immediately. Citrate-anticoagulated blood samples were used for determination of MCP-1 and MCP-3 plasma concentrations. These samples were taken prior to LPS injection and 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, and 24 h thereafter. Samples were centrifuged, and the plasma was stored at −20°C.

Flow cytometry.

Heparinized whole blood was used for flow cytometric analysis. After erythrocytes were lysed by incubation with bicarbonate-buffered ammonium chloride solution (pH 7.4), leukocytes were recovered by centrifugation at 400 × g for 10 min. Cells were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (containing 100 mM EDTA, 0.1% sodium azide, and 5% bovine serum albumin) and washed twice. Staining was done by incubation for 60 min with allophycocyanin-labeled anti-human CD14 antibodies (BD Diagnostic Systems, Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands) and phycoerythrin-labeled anti-human CCR2 antibodies (immunoglobulin G2a subtype; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Monocytes were identified as CD14-positive cells within the monocyte gate. Nonspecific staining was assessed by incubation with phycoerythrin-conjugated mouse immunoglobulin G2a (R&D Systems). Cells were then washed twice in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and resuspended for flow cytometric analysis (Calibur; Becton-Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA). Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was calculated as the difference between MFIs of specifically and nonspecifically stained cells. Data are given as the percentage of baseline MFI values.

MCP-1, MCP-3, and TNF-α assays.

MCP-1, MCP-3, and TNF-α plasma concentrations were measured in duplicate by commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (R&D Systems). Detection limits of the assays were 5 pg/ml.

In vitro studies.

Whole blood of five healthy volunteers was collected in vials containing heparin. Ten milliliters of whole blood was diluted 1:2 with RPMI 1640 medium (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD). LPS (Escherichia coli O55:B5; Difco, Detroit, MI) was added in final concentrations of 100, 10, and 1 ng/ml and 100, 10, 1, 0.1, 0.01, and 0 pg/ml LPS. After 24 h, CCR2 expression was measured as detailed above. CCR2 expression is given as a percentage of the control MFI value (LPS concentration, 0 pg/ml).

Statistics.

All values are given as means ± standard errors (SE). Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (CCR2 surface expression) or Kruskal-Wallis test (chemokine plasma concentrations). Statistical significance was assumed if the P value was <0.05.

Human endotoxemia.

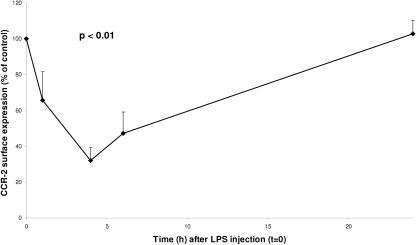

LPS administration elicited transient influenza-like symptoms associated with a febrile response peaking after 4 h (38.4 ± 0.38°C). LPS injection led to a decrease in the number of circulating monocytes. Monocyte counts at the time of fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis were as follows (109 cells/liter): 0.54 ± 0.04 (0 h), 0.01 ± 0.00 (1 h), 0.13 ± 0.06 (4 h), 0.27 ± 0.09 (6 h), and 0.79 ± 0.06 (24 h). LPS injection induced a significant decrease in CCR2 monocyte expression (Fig. 1) (P < 0.01). The most pronounced difference was observed 4 h after injection, when a minimum of 32% of baseline values was reached. Six hours after injection, CCR2 expression had recovered to 47%. A return to baseline values was observed after 24 h. MCP-1 plasma concentrations (picograms per milliliter) are given in Fig. 2. MCP-1 levels were not detectable before LPS injection in any of the volunteers. After LPS administration, MCP-1 plasma levels increased significantly, peaking 4 h after injection. At 24 h, plasma levels were again below the detection limit. TNF-α concentrations (Fig. 2) reached a maximum 2 h after LPS administration (P < 0.01). The values were back to baseline values 6 h after LPS was injected. MCP-3 plasma concentrations did not change in response to LPS and were undetectable in all subjects (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

CCR2 expression on monocytes. Concentration time course of CCR2 expression on monocytes as a percentage of baseline values (100%) after intravenous injection of 4 ng/kg LPS in healthy humans at 0 h is shown. Data are means ± SE. The P value indicates significance for changes over time.

FIG. 2.

Plasma concentrations of MCP-1 (▵) and TNF-α (▪). Mean (±SE) levels of MCP-1 after lipopolysaccharide administration (4 ng/kg) to healthy human volunteers are shown. The P value indicates significance for changes over time.

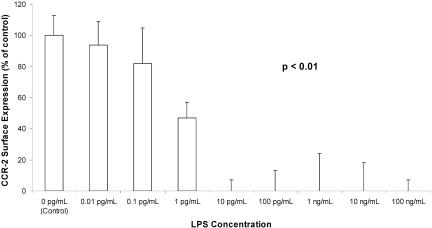

In vitro studies.

After 24 h of incubation, LPS concentrations as low as 10 pg/ml caused a significant decrease of CCR2 surface expression to 0% of control levels (without LPS). One picogram of LPS per milliliter caused a decrease to 47% of the control value. CCR2 expression after exposure to 0.1 and 0.01 pg/ml LPS was 82% and 94%, respectively, compared to the control (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Monocyte CCR2 expression after 24 h of incubation with LPS, shown as a percentage of control values (0 pg/ml LPS). Data are means ± SE. The P value indicates significance for changes over time.

CCR2 density on monocytes is down-regulated during human endotoxemia. This decrease was only transient, and a complete recovery to baseline values was observed 24 h after administration. LPS induced an increase of the plasma concentrations of one of the CCR2 agonists, MCP-1, but not of MCP-3. Peak MCP-1 levels coincided with minimal CCR2 surface expression. Our in vitro data showed that LPS at concentrations as low as 10 pg/ml reduced CCR2 expression to undetectable levels, suggesting that LPS is a very potent trigger of CCR2 down-regulation.

CCR2 is crucial for monocyte migration into inflamed tissues and infection with certain pathogens. Mice with a targeted disruption of CCR2 failed to recruit monocytes in a peritonitis model (5). In addition, animals lacking a functional CCR2 displayed a reduced delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction and granuloma formation (1). CCR2 knockout mice were unable to clear infections with the intracellular pathogen Listeria monocytogenes (5). They were also more susceptible to infections with Leishmania major (9) and Cryptococcus neoformans (11). In vivo regulation of CCR2 surface density could be associated with altered susceptibility to infectious agents.

LPS triggers synthesis and release of a variety of cytokines and chemokines including TNF-α and MCP-1. Xu and colleagues (14) found that concentrations of 100 to 500 ng/ml MCP-1 were required to down-regulate CCR2 surface expression. These MCP-1 concentrations are by far higher than the peak MCP-1 plasma levels of 14 ng/ml observed during our in vivo study (14).

In our study, TNF-α peaked 2 h after LPS administration, i.e., 2 h before the minimum CCR2 expression was observed. Weber et al. found a decrease of monocyte CCR2 to approximately 65% of the control value after the addition of 100 U/ml (12), i.e., 11.4 ng/ml (13). The peak TNF-α concentration in our study was only 2.1 ng/ml.

Based on the reported in vitro effects of MCP-1 and TNF-α, we may speculate that the in vivo plasma concentrations of both molecules after LPS challenge are too low to induce the CCR2 down-regulation in our study.

By contrast, our in vitro data on LPS demonstrated that LPS is a very strong modulator of CCR2 expression.

Taking all these data together, one may speculate that LPS itself is most likely to account for the down-regulation of CCR2 during human endotoxemia.

Twenty-four hours after LPS injection, CCR2 expression returned to the baseline values. Another group had previously defined the fate of the receptor molecules: upon LPS stimulation, CCR2 is internalized and stored in vesicles (14). A rapid recycling of CCR2 molecules from these vesicles to the cell surface could explain the complete recovery of antibody binding 24 h after LPS injection that was observed in our study.

LPS-induced receptor down-regulation is not limited to CCR2. Previous studies reported a decrease of CCR5 as well as of CXC receptors CXCR2 and CXCR4 surface expression (3, 4). No effect on CXCR1 was observed (4). Similar to our study of CCR2, those reports found a transient decrease in receptor density.

CCR2 plays a major role in infection, as suggested by studies of animals with a targeted disruption of this molecule (5). Studies of the regulation of MCP-1/CCR2 could provide further insight into the mechanisms underlying these entities. From the results of our study, we conclude that LPS in vivo induced a transient increase of MCP-1 and a concomitant decrease of CCR2 density on human monocytes. The peak of the MCP-1 increase coincided with the minimal CCR2 expression. A down-regulation of CCR2 counteracts increases of MCP-1, thereby limiting potentially deleterious effects of high concentrations of this chemokine.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the “Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft” (grant no. He 2578/3-1 [M.H.]) and from the Dutch Heart Foundation (grant no. 2001B114 [R.R.]).

REFERENCES

- 1.Boring, L., J. Gosling, S. W. Chensue, S. L. Kunkel, R. V. Farese, Jr., H. E. Broxmeyer, and I. F. Charo. 1997. Impaired monocyte migration and reduced type 1 (Th1) cytokine response in C-C chemokine receptor 2 knockout mice. J. Clin. Investig. 100:2552-2561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charo, I. F., S. J. Myers, A. Herman, C. Franci, A. J. Connolly, and S. R. Coughlin. 1994. Molecular cloning and functional expression of two monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 receptors reveals alternative splicing of the carboxyl-terminal tails. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:2752-2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Juffermans, N. P., S. Weijer, A. Verbon, P. Speelman, and T. van der Poll. 2002. Expression of human immunodeficiency virus coreceptors CXC chemokine receptor 4 and CC chemokine receptor 5 on monocytes is down-regulated during human endotoxemia. J. Infect. Dis. 185:986-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juffermans, N. P., P. E. Dekkers, M. P. Peppelenbosch, P. Speelman, S. J. van Deventer, and T. van der Poll. 2000. Expression of the chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 on granulocytes in human endotoxemia and tuberculosis: involvement of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J. Infect. Dis. 182:888-894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurihara, T., G. Warr, J. Loy, and R. Bravo. 1997. Defects in macrophage recruitment and host defense in mice lacking the CCR2 chemokine receptor. J. Exp. Med. 186:1757-1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsukawa, A., C. M. Hogaboam, N. W. Lukacs, P. M. Lincoln, R. M. Strieter, and S. L. Kunkel. 2000. Endogenous MCP-1 influences systemic cytokine balance in a murine model of acute septic peritonitis. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 68:77-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsukawa, A., C. M. Hogaboam, N. W. Lukacs, P. M. Lincoln, R. M. Strieter, and S. L. Kunkel. 1999. Endogenous monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) protects mice in a model of acute septic peritonitis: cross-talk between MCP-1 and leukotriene B4. J. Immunol. 163:6148-6154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muller, W. A. 2001. New mechanisms and pathways for monocyte recruitment. J. Exp. Med. 194:F47-F51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sato, N., S. K. Ahuja, M. Quinones, V. Kostecki, R. L. Reddick, P. C. Melby, W. A. Kuziel, S. S. Ahuja. 2000. CC chemokine receptor (CCR)2 is required for Langerhans cell migration and localization of T helper cell type 1 (Th1)-inducing dendritic cells: absence of CCR2 shifts the Leishmania major-resistant phenotype to a susceptible state dominated by Th2 cytokines, B cell outgrowth, and sustained neutrophilic inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 192:205-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sica, A., A. Saccani, A. Borsatti, C. A. Power, T. N. Wells, W. Luini, N. Polentarutti, S. Sozzani, and A. Mantovani. 1997. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide rapidly inhibits expression of C-C chemokine receptors in human monocytes. J. Exp. Med. 185:969-974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Traynor, T., W. Kuziel, G. Toews, and G. Huffnagle. 2000. CCR2 expression determines T1 versus T2 polarization during pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection. J. Immunol. 164:2021-2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weber, C., G. Draude, K. S. Weber, J. Wubert, R. L. Lorenz, and P. C. Weber. 1999. Downregulation by tumor necrosis factor-alpha of monocyte CCR2 expression and monocyte chemotactic protein-1-induced transendothelial migration is antagonized by oxidized low-density lipoprotein: a potential mechanism of monocyte retention in atherosclerotic lesions. Atherosclerosis 145:115-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weber, C., M. Aepfelbacher, H. Haag, H. W. L. Ziegler-Heitbrock, and P. C. Weber. 1993. Tumor necrosis factor induces enhanced responses to platelet-activating factor and differentiation in human monocytic Mono Mac 6 cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 23:852-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu, L., M. H. Khandaker, J. Barlic, L. Ran, M. L. Borja, J. Madrenas, R. Rahimpour, K. Chen, G. Mitchell, C. M. Tan, M. DeVries, R. D. Feldman, and D. J. Kelvin. 2000. Identification of a novel mechanism for endotoxin-mediated down-modulation of CC chemokine receptor expression. Eur. J. Immunol. 30:227-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zisman, D. A., S. L. Kunkel, R. M. Strieter, W. C. Tsai, K. Bucknell, J. Wilkowski, and T. J. Standiford. 1997. MCP-1 protects mice in lethal endotoxemia. J. Clin. Investig. 99:2832-2836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]