Phenylalanine hydroxylase (PheH), tyrosine hydroxylase (TyrH), and tryptophanhydroxylase (TrpH) form a small family of non-heme iron monooxygenases which catalyze the insertion of an oxygen atom from molecular oxygen into the aromatic side chain of their corresponding substrates using a tetrahydropterin to reduce the other oxygen atom to the level of water.1,2 Their catalytic domains are homologous, with each containing a single iron atom bound to two conserved histidines and a glutamate, suggesting that all three share a common catalytic mechanism. Despite the structural similarities, the three clearly differ in substrate specificities, in kcat values, and in the identity of the rate-determining step.1–4 All three catalyze benzylic hydroxylation of methylated aromatic amino acids.5–7 In the case of TyrH, the intrinsic kinetic isotope effects for this reaction are consistent with the removal of a hydrogen atom from the methyl group.6 In the present study, a detailed analysis of the intrinsic primary and α-secondary deuterium isotope effects for benzylic hydroxylation by all three enzymes has been carried out as a probe of the relative reactivities of the iron centers.

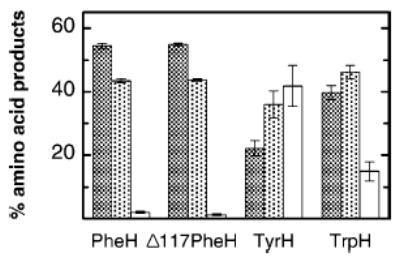

Figure 1 shows the distribution of products when 4-CH3-phenylalanine is used as substrate for wild-type TyrH and PheH3 and for Δ117PheH3 and TrpH102–416,4 mutant forms of PheH and TrpH lacking the N-terminal regulatory domains. For PheH, the percentage of 3-HO-4-CH3-phenylalanine is extremely low, consistent with a strong preference of this enzyme for hydroxylation of the 4-position. The other two enzymes are less specific. Deletion of the regulatory domain of PheH has no effect on the product composition.

Figure 1.

Product distribution with 4-CH3-phenylalanine as substrate for the aromatic amino acid hydroxylases: 4-HOCH2-phenylalanine (dark gray), 3-CH3-4-HO-phenylalanine (light gray), and 3-HO-4-CH3-phenylalanine (white). Reactions were carried out and the products analyzed by HPLC as described in ref 6. Conditions: 25 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, 30μM ferrous ammonium sulfate, 1.2 mM 4-CH3-phenylalanine, 10 μM enzyme, and 150 μM 6-methyltetrahydropterin at 30 °C.

| (1) | (1) |

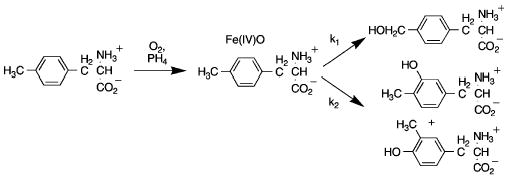

When 4-C2H3-phenylalanine6 is used as substrate, there is a large decrease in the amount of benzylic hydroxylation and a commensurate increase in the amount of aromatic hydroxylation, such that the total amount of hydroxylated amino acids remains the same. The isotope effect on benzylic hydroxylation can be calculated from the change in product composition using the model shown in Scheme 1.8,9 Here, the different hydroxylated amino acid products are formed upon partitioning of the hydroxylating intermediate, proposed to be a ferryl-oxo species resembling that of the heme-based cytochrome P450 in reactivity.2,10 In this model, the fraction of 4-HOCH2-phenylalanine produced is k1/(k1 + k2), and the isotope effect on the percent of benzylic hydroxylation is related to the intrinsic isotope effect on k1 by eq 1. The value of k1H/k2 is readily determined from the products with 4-CH3-phenylalanine. The deuterium isotope effects for benzylic hydroxylation of 4-C2H3-phenylalanine, Dk1, by TyrH, PheH, Δ117PheH, and TrpH102–416 are listed in Table 1. The values for all the enzymes are similar.

Scheme 1.

Table 1.

Intrinsic Isotope Effects on Benzylic Hydroxylation by the Aromatic Amino Acid Hydroxylasesa

| substrate | isotope effect | PheH | Δ117PheH | WT TyrH | TrpH102–416 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-C2H3-phe | Dk1b | 12.4 ± 1.1 | 12.1 ± 1.1 | 13.8 ± 1.2 | 13.0 ± 1.7 |

| 4-CH22H-phe | Dkc | NDd | 9.5 ± 0.4 | 9.5 ± 0.6 | 10.9 ± 0.4 |

| αDkc | ND | 1.12 ± 0.05 | 1.20 ± 0.08 | 1.09 ± 0.03 | |

| 4-CH2H2-phe | Dkc | ND | 7.1 ± 0.2 | 7.6 ± 0.3 | 7.5 ± 0.1 |

| αDkc | ND | 1.31 ± 0.03 | 1.35 ± 0.05 | 1.31 ± 0.02 |

A similar analysis was carried out with 4-CH3-phenylalanine containing one or two deuterium atoms in the methyl group;6 in each case, the decrease in benzylic hydroxylation was less than that seen for the trideuterated substrate, and the resulting isotope effects were also smaller. When the trideuterated substrate is used, hydroxylation requires that a carbon–deuterium bond be broken, and the deuterium isotope effect is a product of a primary and two α-secondary effects, Dk(αDk)2. When the monodeuterated or dideuterated substrate is used, the product 4-hydroxymethylphenylalanine can result from loss of deuterium or hydrogen, so that the observed isotope effects on product composition are more complex combinations of primary and secondary effects. These effects were deconvoluted by determining the relative amounts of hydrogen versus deuterium loss in the 4-hydroxymethylphenylalanine product.9–11 In the case of 4-CH22H-phenylalanine, the ratio of 4-HOCH2H-phenylalanine to 4-HOCH2-phenylalanine is 2Dk/αDk. For 4-CH2H2-phenylalanine, the ratio of the dideuterated to the monodeuterated product is Dk/2αDk. Consequently, the isotopic composition of the 4-hydroxymethylphenylalanine and the intrinsic isotope effect on benzylic hydroxylation for the trideuterated substrate allows calculation of the intrinsic primary and secondary isotope effects. In addition, the results with the mono- and dideuterated substrates provide independent values. These intrinsic isotope effects are listed in Table 1. The results from the two partially deuterated substrates are different, but similar results were obtained for all three enzymes. Intrinsic primary isotope effects of about 10 and α-secondary isotope effects of about 1.1 were found with 4-CH22H-phenylalanine. In contrast, the use of 4-CH2H2- phenylalanine results in intrinsic primary isotope effects less than 8 and α-secondary isotope effects of 1.3 or greater. These isotope effects are consistent with the previously proposed mechanism for benzylic hydroxylation, in which a hydrogen atom is abstracted in a transition sate with significant sp2 character.6 The isotope effects when one deuterium is present in the methyl group are likely to be the intrinsic effects. However, when a second deuterium is present, the motion of the primary hydrogen is coupled to the motion of the second deuterium, resulting in an inflated α-secondary isotope effect and a decreased primary effect.12–14 The intrinsic primary and α-secondary kinetic isotope effects for TyrH, Δ117PheH, and TrpH102–416 are indistinguishable, suggesting that the transition states for CH bond cleavage are similar; this requires that the ferryl-oxo intermediates in all three have similar reactivities.

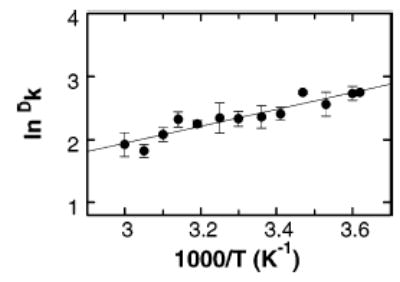

The intrinsic primary isotope effects with the monodeuterated substrate are greater than the upper limit of about 7 predicted by transition state theory. Such large kinetic isotope effects are often interpreted as indicating quantum mechanical tunneling of the hydrogen atom.15–17 Figure 2 shows the temperature dependence of the intrinsic kinetic isotope effect for Δ117PheH. The data from this and similar analyses for TyrH, PheH, Δ117PheH, and TrpH102–416 were fit to the Arrhenius equation to obtain the isotope effects on the Arrhenius pre-exponential factors (AH/AD) and the differences in activation energies (ΔEact). In the absence of tunneling, AH/AD will fall in the range of 0.7–1.4, and ΔEact should not exceed 1.4 kcal mol−1.16,18–20 For all three aromatic amino acid hydroxylases, the values of AH/AD and ΔEact are outside these ranges (Table 2). Since AH/AD < 0.7, the tunneling can be described as moderate, with protium tunneling to a much greater extent than deuterium.17,21 The values for all three enzymes agree well, suggesting that the extent of tunneling is very similar.

Figure 2.

Deuterium kinetic isotope effects for benzylic hydroxylation as a function of temperature for Δ117PheH. Isotope effects were determined from the effects on product composition with 4-C2H3-phenylalanine. The line is from a fit to the Arrhenius equation.

Table 2.

Isotope Effects on Pre-exponential Factors and Differences in Activation Energies for Benzylic Hydroxylation by the Aromatic Amino Acid Hydroxylasesa

| enzyme | AH/AD | ΔEact (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| PheH | 0.18 ± 0.08 | 2.4 ± 0.3 |

| Δ117PheH | 0.13 ± 0.06 | 2.6 ± 0.3 |

| TyrH | 0.11 ± 0.05 | 2.9 ± 0.3 |

| TrpH102–416 | 0.10 ± 0.05 | 2.9 ± 0.3 |

The data presented here are consistent with all three aromatic amino acid hydroxylases catalyzing benzylic hydroxylation via hydrogen atom abstraction, with coupled motion and quantum mechanical tunneling contributions. The similarities of the isotope effects and of the contribution of tunneling suggest that the reactivities of the hydroxylating intermediates are very similar among the three enzymes, irrespective of the presence of a regulatory domain.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Shane Tichy of the TAMU LBMS for assistance with the mass spectrometry, and Drs. Patrick Frantom and Graham Moran for the generous gifts of TyrH and TrpH102–416, respectively. This work was supported by NIH Grant GM47291 and Welch Foundation Grant A1245.

Footnotes

Note Added after ASAP Publication. A change was made on revision in paragraph 5 that should have been made in paragraph 4 instead. After this paper was published ASAP November 2, 2005, the fourth and fifth paragraphs were corrected, and a correction was made to the labeling in Figure 1. The corrected version was published ASAP November 9, 2005.

Supporting Information Available: Arrhenius plots for TyrH, PheH, and TrpH102–416, and tables of isotope effects and of the isotopic content of the hydroxymethylphenylalanine products. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Fitzpatrick, P. F. In Advances in Enzymology and Related Areas of Molecular Biology; Purich, D. L., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 2000; Vol. 74, pp 235–294.

- 2.Fitzpatrick PF. Biochemistry. 2003;42:14083–14091. doi: 10.1021/bi035656u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daubner SC, Hillas PJ, Fitzpatrick PF. Biochemistry. 1997;36:11574–11582. doi: 10.1021/bi9711137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moran GR, Daubner SC, Fitzpatrick PF. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12259–12266. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moran GR, Phillips RS, Fitzpatrick PF. Biochemistry. 1999;38:16283–16289. doi: 10.1021/bi991983j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frantom PA, Pongdee R, Sulikowski GA, Fitzpatrick PF. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:4202–4203. doi: 10.1021/ja025602s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegmund HU, Kaufman S. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:2903–2910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson D, Trager WF. Drug Metab Disp. 2003;31:1481–1498. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.12.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzpatrick, P. F. In Isotope Effects in Chemistry and Biology; Kohen, A., Limbach, H., Eds.; Marcel Dekker: New York, 2005; pp 861–873. This model assumes that the intial attack of the hydroxylating intermediate on the substrate is irreversible, so that there are no internal commitments in k1 or k2 This has not been explicitly established but is reasonable based on the following: (1) oxygenation reactions are typically irreversible; (2) the isotope effects are large; and (3) the Arhennius plots are linear over large temperature ranges.

- 10.Bassan A, Blomberg MRA, Siegbahn PEM. Chem– Eur J. 2003;9:4055–4067. doi: 10.1002/chem.200304768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanzlik RP, Hogberg K, Moon JB, Judson CM. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:7164–7167. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook PF, Oppenheimer NJ, Cleland WW. Biochemistry. 1981;20:1817–1825. doi: 10.1021/bi00510a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hermes JD, Morrical SW, O’Leary MH, Cleland WW. Biochemistry. 1984;23:5479–5488. doi: 10.1021/bi00318a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huskey WP, Schowen RL. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:5704–5706. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bell, R. P. The Tunnel Effect in Chemistry; Chapman & Hall: New York, 1980.

- 16.Klinman, J. P. In Enzyme Mechanism from Isotope Effects; Cook, P. F., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 1991; pp 127–148.

- 17.Kohen A, Klinman JP. Chem Biol. 1999;6:191–198. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(99)80058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bell RP. Chem Soc Rev. 1974;3:513–544. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kin Y, Kreevoy MM. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:7116–7123. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneider ME, Stern MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:1517–1522. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohen A, Klinman JP. Acc Chem Res. 1998;31:397–404. [Google Scholar]