Abstract

Ojbective:

To evaluate the relationship among appropriateness of the use of cholecystectomy and outcomes.

Summary Background Data:

The use of cholecystectomy varies widely across regions and countries. Explicit appropriateness criteria may help identify suitable candidates for this commonly performed procedure. This study evaluates the relationship among appropriateness of the use of cholecystectomy and outcomes.

Methods:

Prospective observational study in 6 public hospitals in Spain of all consecutive patients on waiting lists to undergo cholecystectomy for nonmalignant disease. Explicit appropriateness criteria for the use of cholecystectomy were developed by a panel of experts using the RAND appropriateness methodology and applied to recruited patients. Patients were asked to complete 2 questionnaires that measure health-related quality of life—the Short Form 36 (SF-36) and the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI)—before the intervention and 3 months after it.

Results:

Patients judged as being appropriate candidates for cholecystectomy, using the panel's explicit appropriateness criteria, had greater improvements in the bodily pain, vitality, and social function domains of the SF-36 than those judged to be inappropriate candidates. They also demonstrated improvements in the GIQLI's physical impairment domain. Interventions judged as inappropriate were performed primarily among patients without symptoms of cholelithiasis. Those asymptomatic had a lower improvement in the bodily pain, social functioning, and physical summary scale of the SF-36 and in the symptomatology, physical impairment, and total score domains of the GIQLI.

Conclusions:

These results suggest a direct relationship between the application of explicit appropriateness criteria and better outcomes, as measured by health-related quality of life. They also indicate that patients without symptoms are not good candidates for cholecystectomy.

This study evaluates the relationship among cholecystectomy appropriateness criteria and outcomes. The criteria were applied to patients who underwent cholecystectomy. Patients were asked to complete 2 health-related quality-of-life questionnaires before and after the intervention. The results suggest a direct relationship between the explicit appropriateness criteria and outcomes.

The ability to maintain or enhance quality of care in an increasingly cost-conscious environment may depend on the ability to determine the appropriateness of care. By definition, a procedure is considered appropriate if its health benefit exceeds its health risk by a sufficiently wide margin, thus making the procedure worth performing.1 Applying this definition to clinical care requires determining what constitutes appropriate indications for a given procedure. A method that combines expert opinion with available scientific evidence to create explicit appropriateness criteria was developed by investigators at the RAND Corporation and the University of California at Los Angeles.2

Cholecystectomy is a commonly performed procedure. Although its use is still increasing in most developed countries,3 surgical rates vary moderately across regions and countries,4,5 a finding not explained solely by differences in the prevalence of gallbladder disease. Variations in clinical decision-making likely contribute to this variation. Previous RAND methodology-based studies of this procedure were performed in the early 1980s in the United States6 and in the late 1980s in Israel7 and the United Kingdom.8 The criteria developed by those studies are no longer useful since they did not include new variables such as the use of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or new imaging tests such as echography. To update the explicit appropriateness criteria for cholecystectomy, a new panel of experts was formed in 2000.9 Although partial validation of the new criteria has been published,9 an important issue was to validate those criteria against relevant outcomes.

Greater importance is now being given to measuring the HRQoL when evaluating the outcome of medical interventions, particularly with regard to chronic diseases.10 The measurement of HRQoL is increasingly being used in the field of gastroenterology and digestive surgery to evaluate the evolution of certain digestive diseases and to ascertain the effectiveness of medical or surgical treatments. It is also being applied not only to chronic diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease or liver diseases but also to digestive surgery, transplants, or oncological problems.11,12

We conducted a prospective observational study to validate the newly developed explicit appropriateness criteria for cholecystectomy by looking at the relationship between appropriateness evaluation and outcomes measured by 2 HRQoL instruments, the SF-36 Health Survey (SF-36) and the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI). We hypothesized that patients considered appropriate for cholecystectomy would have higher HRQoL improvement on some domains of these instruments. We also wanted to determine if there were subclasses of patients with lower HRQoL improvements who might not benefit from cholecystectomy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Explicit Criteria Development

The criteria for measuring the appropriateness of the use of cholecystectomy were developed according to the previously described RAND appropriateness method.2 In brief, it consists of the following steps.

First, an extensive literature review was performed to summarize existing knowledge concerning efficacy, effectiveness, risks, costs, and opinions about the use of cholecystectomy to treat nonmalignant diseases.

Second, from this review, a comprehensive and detailed list of mutually exclusive and clinically specific scenarios (indications) was developed in which cholecystectomy might be performed. This list contained 414 indications for cholecystectomy. Each indication was specified in sufficient detail that patients within a given indication were reasonably homogeneous. A detailed description of the variables and their categories and definitions has been published elsewhere.9 Variables that were considered to create the indications were patient age, surgical risk (measured by the American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA]13), diagnosis (symptomatic cholelithiasis without complications; symptomatic cholelithiasis with complications such as cholecystitis, choledocholithiasis, pancreatitis or cholangitis; asymptomatic cholelithiasis; and a miscellaneous category that included imaging findings such as porcelain gallbladder, polyps, and cholesterolosis), gallbladder and common bile duct imaging studies, the performance of previous nonsurgical procedures such as ERCP (successful or not), and the presence of special circumstances such as diabetes.

Third, we formed a national panel of experienced surgeons (n = 6) and gastroenterologists (n = 6). Panelists were nationally recognized specialists in the field whose names were provided by their respective medical societies and members of our research team. The panelists were provided with the literature review and the list of indications and asked to rate each indication for the appropriateness of performing cholecystectomy, considering the average patient and average physician in the year 1999. Appropriateness was defined to mean that the expected health benefit would exceed the expected risks by a sufficiently wide margin to make cholecystectomy worth performing, after choosing the best surgical alternative available for the patient (open cholecystectomy, minicholecystectomy, or laparoscopic cholecystectomy).

Ratings were scored on a 9-point scale. The use of cholecystectomy for a specific indication was considered appropriate if the panel's median rating was between 7 and 9 without disagreement, inappropriate if the value was between 1 and 3 without disagreement, or uncertain if the median rating was between 4 and 6 or if panel members disagreed. Agreement was defined as no more than 3 panelists rating the indication outside the 3-point region (1–3, 4–6, 7–9) containing the median. Disagreement was defined as at least 4 of the panelists rating an indication from 1 to 3 and at least 4 others rating it from 7 to 9. Indeterminate ratings were those for which neither agreement nor disagreement was found. This method did not attempt to force panelists to reach consensus on appropriateness.

It was beyond the scope of the panel's work to compare the use of open cholecystectomy with laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The panelists were instructed to evaluate the appropriateness of performing any cholecystectomy technique against other nonsurgical treatments, such as watchful waiting. The panelists were instructed not to evaluate the appropriate timing of the intervention (urgent or as an interval operation), only whether the intervention itself was appropriate.

The ratings were confidential and took place in 2 rounds, using a modified Delphi process.14 In the first round, the experts rated the indications in private before the panel meeting. In the second round, completed during a 1-day meeting, each panelist received the anonymous ratings of the other panelists, as well as a reminder of his or her own scores. After extensive discussion, panelists revised the indications according to the new definitions presented during the second round. Each panelist rated 390 separate indications during the first round and 414 indications during the second round because a new age category was added in some cases. Results of part of the work of the panel of experts were included in a previous publication.9

Data Collection

This prospective observational study took place in 6 public hospitals (4 university affiliated and 2 community based) all belonging to the Basque Health Service-Osakidetza, a local government agency in the Basque Country, which is part of the Spanish National Health Service (SNHS). Physicians in each hospital were blinded to the study goals.

Consecutive patients undergoing cholecystectomy, who were followed in any of the 6 hospitals, were eligible for the study. Patients with malignant, severe organic, or psychiatric diseases were excluded. Between March 1999 and March 2000, 1009 patients were entered on waiting lists. Of these, 9 with malignant diseases were excluded. Of 1000 patients who fulfilled the selection criteria, medical records were accessible and reviewed for 963. Of these, 650 presented with symptomatic cholelithiasis (1 or more biliary colics) or asymptomatic cholelithiasis and completed the questionnaires sent to them before the intervention, while 509 (78.3%) completed the questionnaires both before and 3 months after the intervention. This is the sample included in this study.

To collect data and determine appropriateness, we developed a computerized algorithm based on the results of our panel. We also developed data collection questionnaires that included variables before the intervention, admission, and discharge, including the intervention, and complications at 3 months after discharge. Besides those variables belonging to the appropriateness algorithm, other variables collected included sociodemographic data, height, weight, main complaint, comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, cardiac disease, dementia, depression, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, cancer, renal disease, hepatic disease, anemia, and arthritis), previous interventions, intervention characteristics, local and general complications peri- and postintervention, reintervention, death, and length of hospital stay.

All patients on the waiting list for cholecystectomy received a letter informing them about the study and asking for their voluntary participation. They were sent the SF-36 and GIQLI questionnaires, as well as additional questions on the clinical aspects of their disease (number of colics experienced in the last year, total number of colics, presence of complications, and comorbidities) on sociodemographic information. Those patients who had not replied after 15 days were sent another letter; those who had still not replied after a further 15 days were again sent the questionnaire and were also contacted by phone. Three months after the intervention, patients were sent the same questionnaires and a single question on patient satisfaction with the intervention. Follow-up of those not replying was as described above.

The SF-36 is a generic HRQoL instrument for measuring the quality of life. Its 36 questions cover 8 domains (physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional, and mental health). The scores for the SF-36 scales are obtained using the Likert score adding method.15 The scores can range from 0 to 100, with a high score indicating a better health status. A single health transition item is also included. It asked the patient to rate his health compared with 1 year ago. The SF-36 has been translated into Spanish and validated in Spanish populations.16,17

The GIQLI was developed in Germany by Eypasch et al in 1993.18,19 This questionnaire includes both specific questions on gastrointestinal symptoms, for both the upper and lower digestive tracts, as well as questions on physical, emotional, and social capabilities. It is considered to be a mixed questionnaire that includes both generic and specific questions. The 36 questions are answered using a response scale from 0 to 4 for each question (where 0 is the worst and 4 is the best appraisal). The GIQLI includes 5 domains: symptoms (19 questions), physical dysfunction (7 questions), emotional dysfunction (5 questions), social dysfunction (4 questions), and the effects of the medical treatment carried out (1 question). The sum of each of the responses to the questions for each scale, divided by the number of questions in the scale, gives the score for each scale. There is also an overall score that can range from 0 to 144 points. The GIQLI has been translated into Spanish and validated in Spain.20

A single question was included to measure patient satisfaction with the intervention (“How satisfied you feel with the outcome of the intervention?” Answer scale from very satisfied to not at all satisfied. Five categories).

Three reviewers collected data from the patients’ medical records via a standardized questionnaire. The reviewers were blinded to the specific study goals. At 3 months after discharge, all medical records were again reviewed to determine if the patient had been readmitted, died, or had any complication resulting from the intervention.

Statistical Analysis

The unit of study was the patient. Descriptive statistics included frequency tables, mean and standard deviations. χ2 and Fisher exact test tests were used to test for statistical significance among proportions. For continuous variables (eg, age), ANOVA test was performed in the univariate analysis. Student t test was performed to test for statistically significant differences among the study groups: those appropriate versus those less than appropriate (uncertain and inappropriate), and those symptomatic versus those asymptomatic. We included patients in the uncertain category with the inappropriate cases, as was done in previous RAND studies.21,22 We did this to focus on the improvement of those judged appropriate for cholecystectomy versus those judged not appropriate and also because we found very few inappropriate cases in our sample.

All effects are significant at P < 0.05, unless otherwise noted. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS for Windows statistical software, version 8.0.

RESULTS

During the 1-year recruitment period, 650 patients fulfilled the selection criteria and agreed to participate in the study. The mean age was 56 years, and 72.5% were women. In the entire sample, 97 (14.9%) had an asymptomatic cholelithiasis.

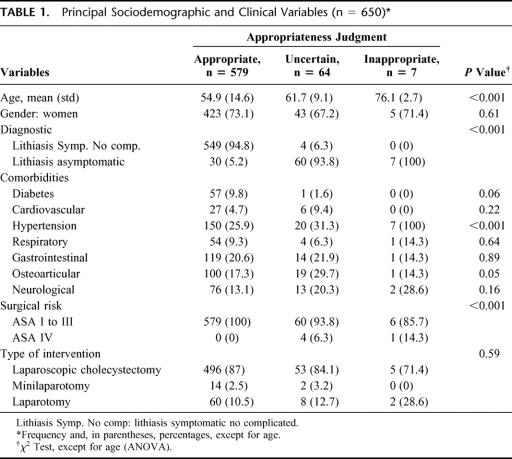

After applying the explicit appropriateness criteria developed by our expert panel, 579 cases (89.1%) were considered appropriate candidates for cholecystectomy, 64 (9.9%) uncertain, and 7 (1.1%) inappropriate. Differences among the 3 appropriateness categories were found by age, diagnosis group, 1 comorbidity (hypertension), and surgical risk (Table 1). Most patients underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy (86.6%). The use of different surgical techniques—laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus open surgery—by appropriateness showed a higher percentage of appropriate interventions in patients treated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy, though not statistically significant (P = 0.41).

TABLE 1. Principal Sociodemographic and Clinical Variables (n = 650)

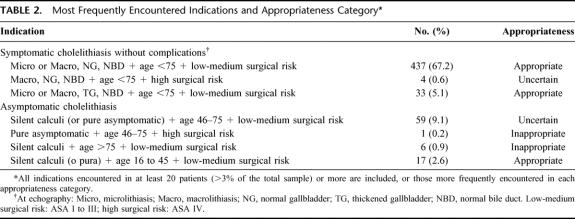

The most frequently encountered indications are shown in Table 2. These data show that inappropriate indications were concentrated among patients who were asymptomatic, those with silent calculi, and classified as ASA I-III, and the only one asymptomatic patient classified as ASA IV. Those asymptomatic with low to medium surgical risk (ASA I to III) tended to be in the uncertain category, while symptomatic patients clustered in the appropriate category.

TABLE 2. Most Frequently Encountered Indications and Appropriateness Category

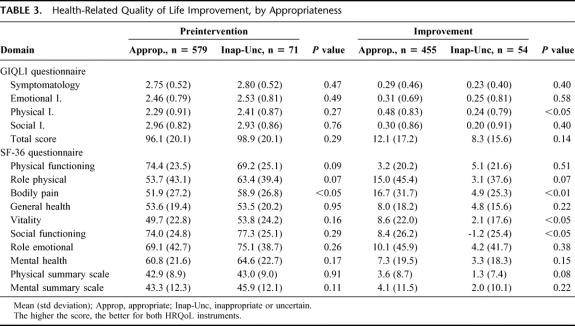

To measure health-related quality of life in these patients, we used a gastrointestinal symptoms specific instrument (GIQLI) and a generic (SF-36) questionnaire. No differences were found among those considered appropriate versus those classified as uncertain/inappropriate in any of the 4 domains of the GIQLI nor its total score before the intervention. When looking at the improvement 3 months after surgery, the physical impairment domain showed a higher improvement for those classified as appropriate versus the uncertain/inappropriate cases (Table 3). On the other hand, SF-36 bodily pain scores were lower for those considered appropriate for cholecystectomy. The improvement 3 months after the intervention was higher for those considered as appropriate in the bodily pain, vitality, and social functioning domains (Table 3). The level of satisfaction with treatment was lower among those classified as uncertain/inappropriate (9.3% of negative evaluations) than among those classified as appropriate for cholecystectomy (2.2% of negative evaluations). This difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05).

TABLE 3. Health-Related Quality of Life Improvement, by Appropriateness

We recorded the mortality rate (0%), local (19.9%) and general (6%) complication rates during the intervention or admission, and length of stay (3.5 days) for the entire sample. At 3 months, we also recorded the mortality rate (0%), local (4.5%) and general (3.9%) complication rates, and readmissions (0.3%) resulting from the intervention. No statistically significant differences in these outcomes were observed between the appropriate and the uncertain/inappropriate groups.

HRQoL improvement was evaluated for the 2 main type of surgical interventions, laparotomy versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy. No statistically significant differences were apparent in any of the GIQLI or SF-36 domains.

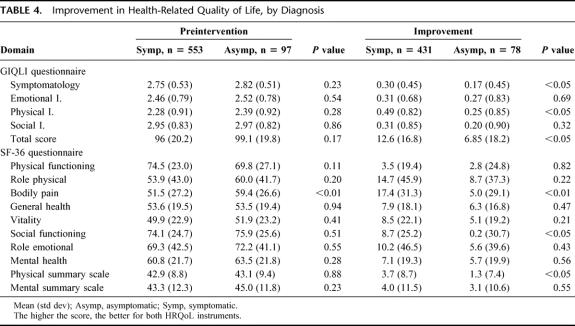

Since the inappropriate cases were concentrated in asymptomatic patients, we compared the HRQoL between asymptomatic patients and those with symptomatic cholelithiasis. As measured by the GIQLI, no differences were observed preintervention between patients asymptomatic and with symptomatic lithiasis. The improvements recorded after the intervention were higher for symptomatic patients on the symptomatology and physical impairment domains and in the GIQLI total score (Table 4). The SF-36, in this case, captured a statistically significant preintervention difference between asymptomatic and symptomatic patients in the bodily pain domain, with lower scores among symptomatic patients. When looking at improvements after the intervention, the bodily pain and social functioning domains, as well as the physical summary score, showed a greater improvement for symptomatic patients (Table 4). The level of satisfaction was lower among asymptomatic patients (6.5% of negative evaluations) than among symptomatic patients (2.3% of negative evaluations), a statistically significant (P < 0.05) difference.

TABLE 4. Improvement in Health-Related Quality of Life, by Diagnosis

The use of laparoscopic cholecystectomy and open surgery by diagnosis group was similar. We also looked at differences in mortality, complications, and readmissions by surgery type and found no statistically significant differences.

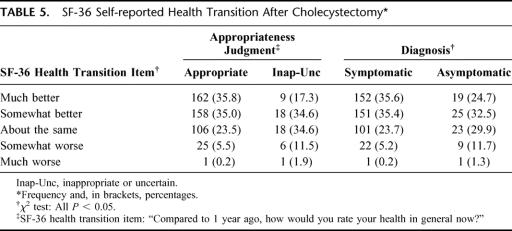

The SF-36 includes a single health transition item, which requests the patient to rate his health compared with 1 year ago. Again, appropriate and symptomatic patients had a higher perception of improvement than the uncertain-inappropriate and asymptomatic (Table 5). Of those uncertain-inappropriate patients, 13.4% rate their health as worse, while 5.7% of the appropriate. Of those asymptomatic, 13% rate their health as worse, while 5.4% of the symptomatic.

TABLE 5. SF-36 Self-reported Health Transition After Cholecystectomy

DISCUSSION

This study prospectively assessed the appropriateness of surgical indications for patients undergoing cholecystectomy for nonmalignant diseases in a region of Spain in 1999 to 2000 using updated appropriateness criteria developed by a national panel of experts. The main goal of this study was to evaluate the validity of the explicit appropriateness criteria developed by the panel by predicting relevant outcomes. To our knowledge, no studies have been published thus far that examine the relationship between explicit appropriateness criteria and HRQoL outcomes. We did this by providing the patients with 2 questionnaires, the generic SF 36 and one specific to gastrointestinal health, the GIQLI, at 2 points in time: once while waiting for cholecystectomy and again 3 months after the intervention. Classic clinical outcomes such as mortality, morbidities due to the surgical intervention, and quality of care indicators such as readmission or length of stay were also measured.

Our main hypothesis was that patients classified by the explicit criteria as appropriate for cholecystectomy would have higher HRQoL improvements than those deemed inappropriate for this procedure. Appropriateness definition used by RAND investigators considered a procedure appropriate if the “expected health benefit exceeds the expected negative consequences by a sufficiently wide margin.”1 Our results support in part our hypothesis that those considered as appropriate interventions had a higher HRQoL gain. Both the SF-36 and the GIQLI demonstrated such improvement. With the GIQLI, improvements were recorded only in the physical impairment. Surprisingly, the generic SF-36 showed improvements in more domains than the GIQLI: the bodily pain, vitality, and social functioning domains. An improvement in the bodily pain domain is an important finding, since this should be the main domain for improvement in these patients regarding an intervention such as cholecystectomy. When patients rated their health compared with 1 year ago, a higher proportion of those considered uncertain or inappropriate rated it as worse. The level of satisfaction after the intervention was also higher for those classified as appropriate. The “expected negative consequences,” including local or general complications, mortality, or readmissions, were similar among both groups. So, the final balance indicated that for a similar risk, the benefit was higher for those judged as appropriate indications. In our study, uncertain and inappropriate cases were concentrated among patients with a diagnosis of asymptomatic cholelithiasis and high surgical risk, measured by the ASA. Patient age also played a role, as older patients were more frequently classified as inappropriate for cholecystectomy.

Another hypothesis we tested was whether asymptomatic patients had lower HRQoL improvements than symptomatic patients. As far as we know, no such prospective studies to date have compared symptomatic versus asymptomatic cholelithiasis where the outcome measures have been the patient's HRQoL perception. In this case, the bodily pain domain of the SF-36 showed a significantly greater improvement for symptomatic patients, as well as the health transition item, while the GIQLI showed significant improvements in the physical impairment and symptomatology domains. In addition, the level of satisfaction after the intervention was significantly higher for symptomatic patients. Classically, asymptomatic cholelithiasis has not been considered an indication for prophylactic cholecystectomy, because of its benign course. Asymptomatic cholelithiasis becomes symptomatic annually in 1% to 4% of cases, reaching 20% at 20 years, and almost always presents with previous symptoms before complications develop.23–26 Our results support a conservative approach regarding the indication of cholecystectomy for patients with silent calculi, based on the panel criteria and in the low HRQoL improvement showed.

Our study has some limitations. Those related to the development of the RAND explicit appropriateness criteria and the expert panel's work have been discussed in our previous study9 and several other publications.6,8,21,22 Despite these criticisms, the RAND appropriateness methodology has been considered an adequate tool for utilization review. With regard to data collection, the 3 blinded reviewers who collected the data were physicians trained to assess and record the main variables of the algorithm in a standardized manner to reduce the chances of bias. During their training, we checked their reliability and accuracy, with excellent correlations. However, the quality of data derived exclusively from medical records for some important variables may introduce the chance for information bias that may influence the final appropriateness judgment. In our case, most relevant variables (age, surgical risk, diagnosis, comorbidities) were adequately recorded. Recommendations made for utilization review studies and uses of HRQoL instruments were followed.27,28

A main issue here is the choice of the most appropriate outcome measures to capture relevant changes after a cholecystectomy. Clinical parameters have almost always been the measures chosen by most investigators, even in recent studies focusing on cholecystectomy.29–31 In a few studies, other parameters such as HRQoL instruments have been chosen as the main outcome measure. We chose 2 HRQoL instruments, the SF-36 and the GIQLI, to try to capture the relevant changes after a cholecystectomy. The generic SF-36 has the advantage of being a well-known and widely used instrument that allows us to compare our results to other studies of other diseases or procedures. The main disadvantage is the lower discriminative ability of a generic instrument and its lack of specificity for capturing the important changes produced in a particular clinical problem. Thus we added the GIQLI, which has been used in several gastrointestinal studies.12 It is more specific than the SF-36, focusing on gastrointestinal symptoms in both the upper and lower tracts. It also includes domains of general health that are normally affected in patients suffering from gastrointestinal pathologies. Several other HRQoL instruments specific for cholelithiasis or cholecystectomy exist, but they are either longer, their psychometric properties have not been well studied, or have not been translated into Spanish.32–34

The improvements we found in the bodily pain domain of the SF-36 for individuals symptomatic, and also on those interventions judged as appropriate, were approximately 17 points. Some authors suggested a 10 points improvement in any SF-36 domain, or more than 10%, as being clinically meaningful.35 Therefore, a 17-point improvement in the bodily pain domain of the SF-36 seems to be clinically relevant. In the same group, the total GIQLI score improved approximately 12 points, which is also over the suggested 10% clinically meaningful improvement.

Both of these instruments have been used in studies of patients with cholelithiasis undergoing cholecystectomy. Improvements in the GIQLI were quite similar to ours.18,19 Of those where the SF-36 was used,36,37 one demonstrated a median improvement in the bodily pain domain of 30 points for patients who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy and no improvement for those who underwent open surgery.37 These improvements are much higher than what we observed, even among patients judged appropriate for cholecystectomy. Nevertheless, these previous studies included very small sample sizes, which importantly limited their conclusions.

Clearly, more research is needed to determine which outcome measures better capture the changes produced by the intervention, in this case, reduction of gastrointestinal symptoms and pain in patients selected for cholecystectomy. Even so, the instruments we used were sensitive enough and responsive enough to capture reductions in symptoms and thus appear to be appropriate for measuring outcomes associated with cholecystectomy. However, both the generic SF-36 and the more specific GIQLI have limitations that could be addressed by the development of better instruments.

We only included in this study patients with cholelithiasis, either symptomatic or not. There are some other clinical situations included in our appropriateness algorithm though not in this study, as patients with suggestive symptoms but without cholelithiasis.9 But cholecystectomy has been used in other clinical situations included neither in our algorithm nor in this study. Therefore, the use of our criteria and the results of this study must be done carefully, since now or in the future some other clinical situations where the use of cholecystectomy is evidence-based can arise. And, as suggested by the authors of the RAND appropriateness method,38 if appropriateness is to be improved it must be assessed at the level of each patient, hospital, and physician.

In conclusion, the results of this prospective observational study support the predictive validity of an explicit appropriateness criteria tool by showing a greater benefit in HRQoL for cholecystectomy among patients considered by a panel of experts as appropriate for this procedure than those classified as uncertain or inappropriate. These results support the use of appropriateness criteria to determine the degree of appropriateness and variations in the use of cholecystectomy. Although variation in the indication of cholecystectomy is potentially attributable to variation in clinical decision-making, other issues, as for instance lack of human or technical resources on a specific center, can undermine the potential applicability of our findings in other settings.

Surgery was more likely to be considered inappropriate in patients with asymptomatic cholelithiasis, which matches current state-of-the-art criteria about the indication of cholecystectomy for patients with gallbladder disease.29 In addition, our results demonstrated that asymptomatic patients derived less benefit from cholecystectomy than symptomatic patients, which supports a conservative approach for patients without symptoms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the following individuals for their contributions to this study: Drs. Aguado, Arenas, Atín, Baile, Barrios, Casanova, Hinojosa, Lanas, Monés, Pons, Robles, Sarabia, Suárez Alzamora, Valdivieso and Zaballa. Also to Y. Echeverria, I. Garay, A. Higelmo, I. Lafuente, A. Rodriguez and I. Vidaurreta for their contribution to the development of the panel of expert, data retrieval and data introduction. The authors thank the support of the staff members of the different services, research and quality units, as well as the medical records sections of the participant hospitals. We also wish to thank to the Research Committee of Galdakao Hospital for their help in the editing work of this manuscript.

Footnotes

This study was partially supported by a grant from the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (98/002-03). Amaia Bilbao received a grant from the Department of Health of the Basque Government.

Address correspondence to: José MŞ Quintana, MD, Unidad de Investigación, Hospital de Galdakao, Barrio Labeaga s/n, 48960 Galdakao, Vizcaya, Spain. E-mail: jmquinta@hgda.osakidetza.net.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brook RH. Appropriateness: the next frontier. BMJ. 1994;308:218–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brook RH, Chassin MR, Fink A, et al. A method for the detailed assessment of the appropriateness of medical technologies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1986;2:53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johanning JM, Gruenberg JC. The changing face of cholecystectomy. Am Surg. 1998;64:643–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McPherson K, Wennberg JE, Hovind OB, et al. Small-area variations in the use of common surgical procedures: an international comparison of New England, England, and Norway. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:1310–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pilpel D, Fraser GM, Kosecoff J, et al. Regional differences in appropriateness of cholecystectomy in a prepaid health insurance system. Public Health Rev. 1992;20:61–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park RE, Fink A, Brook RH, et al. Physician ratings of appropriate indications for six medical and surgical procedures. Am J Public Health. 1986;76:766–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraser GM, Pilpel D, Hollis S, et al. Indications for cholecystectomy: the results of a consensus panel approach. Qual Assur Health Care. 1993;5:75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott EA, Black N. Appropriateness of cholecystectomy in the United Kingdom: a consensus panel approach. Gut. 1991;32:1066–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quintana JM, Cabriada J, López de Tejada I, et al. Development of explicit criteria for cholecystectomy. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11:320–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Patrick DL. Measuring health-related quality of life. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:622–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borgaonkar MR, Irvine EJ. Quality of life measurement in gastrointestinal and liver disorders. Gut. 2000;47:444–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yacavone RF, Locke GR 3rd, Provenzale DT, et al. Quality of life measurement in gastroenterology: what is available? Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:285–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneider AJ. Assessment of risk factors and surgical outcome. Surg Clin North Am. 1983;63:1113–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dalkey NC, Brown BB, Cochran S. The Delphi Method. Santa Monica, Calif: Rand Corp; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36), I: conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alonso J, Prieto L, Anto JM. The Spanish version of the SF-36 Health Survey (the SF-36 health questionnaire): an instrument for measuring clinical results. Med Clin (Barc). 1995;104:771–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alonso J, Prieto L, Ferrer M, et al. Testing the measurement properties of the Spanish version of the SF-36 Health Survey among male patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Quality of Life in COPD Study Group. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1087–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eypasch E, Wood-Dauphinee S, Williams JI, et al. The Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index: a clinical index for measuring patient status in gastroenterologic surgery. Chirurg. 1993;64:264–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eypasch E, Williams JI, Wood-Dauphinee S, et al. Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index: development, validation and application of a new instrument. Br J Surg. 1995;82:216–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quintana JM, Cabriada J, López de Tejada I, et al. Translation and validation of the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI). Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2001;93:700–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hilborne LH, Leape LL, Bernstein SJ, et al. The appropriateness of use of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty in New York State. JAMA. 1993;269:761–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leape LL, Hilborne LH, Schwartz JS, et al. The appropriateness of coronary artery bypass graft surgery in academic medical centers: Working Group of the Appropriateness Project of the Academic Medical Center Consortium. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:8–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.NIH Consensus conference. Gallstones and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. JAMA. 1993;269:1018–1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strasberg SM, Clavien PA. Overview of therapeutic modalities for the treatment of gallstone diseases. Am J Surg. 1993;165:420–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mulvihill SJ, Somberg KA. Surgical management of biliar lithiasis and postoperatory complications. In: Sleisenger MH, Fordtran JS, eds. Gastrointestinal Disease: Pathology, Diagnosis, Management. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1994:1881–1889. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedman GD. Natural history of asymptomatic and symptomatic gallstones. Am J Surg. 1993;165:399–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naylor CD, Guyatt GH. Users’ guides to the medical literature, XI: how to use an article about a clinical utilization review: Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1996;275:1435–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guyatt GH, Naylor CD, Juniper E, et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature, XII: how to use articles about health-related quality of life: Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1997;277:1232–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bateson MC. Fortnightly review: gallbladder disease. BMJ. 1999;318:1745–1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McMahon AJ, Fischbacher CM, Frame SH, et al. Impact of laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a population-based study. Lancet. 2000;356:1632–1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zacks SL, Sandler RS, Rutledge R, et al. A population-based cohort study comparing laparoscopic cholecystectomy and open cholecystectomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cleary PD, Greenfield S, McNeil BJ. Assessing quality of life after surgery. Control Clin Trials. 1991;12(4 suppl):189S–203S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cleary R, Venables CW, Watson J, et al. Comparison of short term outcomes of open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Qual Health Care. 1995;4:13–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Russell ML, Preshaw RM, Brant RF, et al. Disease-specific quality of life: the Gallstone Impact Checklist. Clin Invest Med. 1996;19:453–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osoba D. A taxonomy of the uses of Health-Related Quality of Life instruments in cancer care and the clinical meaningfulness of results. Med Care. 2002;40:III-31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Temple PC, Travis B, Sachs L, et al. Functioning and well-being of patients before and after elective surgical procedures. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181:17–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Velanovich V. Laparoscopic vs open surgery: a preliminary comparison of quality-of-life outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brook RH, Park RE, Chassin MR, et al. Predicting the appropriate use of carotid endarterectomy, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, and coronary angiography. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1173–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]