Abstract

Objective:

This study analyzes the role of phosphatidylserine receptor (PSR) in chronic pancreatitis.

Summary Background Data:

In chronic pancreatitis, destruction of parenchyma comes along with infiltration of lymphocytes and macrophages. The phosphatidylserine receptor is expressed on the surface of macrophages and is crucial for the recognition and engulfment of apoptotic cells. In the present study, we investigated the role of this receptor and its relation to apoptosis in chronic pancreatitis.

Methods:

The expression and localization of PSR were analyzed by Northern blot analysis, RT-PCR, Western blot analysis and immunohistochemistry. Apoptosis was detected by the TUNEL method, and the RNA protection assay (RPA) was used to compare activation of apoptosis with PSR mRNA expression levels. In addition, the molecular data were related to clinicopathological parameters.

Results:

PSR mRNA expression was low to absent in normal pancreatic tissue samples. In human chronic pancreatitis, increased expression of PSR mRNA was present in 12 of 29 samples (41%). Up-regulation of PSR could be confirmed by Western blot analysis. In chronic pancreatitis tissue, PSR immunoreactivity was present in all islets, in some ductal cells and in macrophages. The RNA protection assay revealed high mRNA levels of the antiapoptotic genes bcl-2 and bfl-1 (P < 0.05) in chronic pancreatitis tissues with high PSR mRNA expression. The TUNEL apoptosis in situ detection method showed positive signals in some redifferentiating acinar cells and focally in acinar cells adjacent to stromal fibroblasts in chronic pancreatitis tissue samples. The distribution pattern of PSR on pancreatic cells in chronic pancreatitis corresponded to a great extent with regions of high apoptotic activity.

Conclusions:

We show for the first time the presence of PSR in chronic pancreatitis on pancreatic cells other than macrophages in regions with high apoptotic activity. The coexpression and colocalization of this gene with other apoptosis mediators suggest its involvement in apoptotic processes. However, in chronic pancreatitis PSR is not only involved in phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages.

The phosphatidylserine receptor (PSR) is the crucial factor in the engulfment of apoptotic cells by macrophages. In the present study, we found PSR for the first time on degenerating acinar cells and on acinar cells dedifferentiating into tubular structures in chronic pancreatitis. These findings indicate a new but presently still unknown function of this apoptosis-related receptor.

Clearance of apoptotic or necrotic cells by phagocytes protects the surrounding tissue from toxic intracellular factors and reduces probable tissue damage following an inappropriate inflammatory reaction.1 Phosphatidylserine (PS) is one of the key factors in induction of phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. It is the most abundant anionic phospholipid of the plasma membrane, which is located at the inner leaflet of the cell surface.2 The loss of asymmetry and the appearance of this molecule on the outer leaflet of the cell membrane is regarded as one of the essential steps in apoptosis and subsequently in phagocytosis of apoptotic cells.3–7 If apoptotic cells are unable to express PS on their surface, it is almost impossible for them to be phagocytosed.6 However, in addition to the presentation of PS, apoptotic cells display numerous receptors on their surfaces, such as CD 36, αvβ3, αvβ5 integrins, CD14 and CD68. These are necessary in order for phagocytes to approach apoptotic cells, but only the interplay with the PS receptor enables their internalization.8

Binding of PS on the apoptotic cell surface to the PS-receptor (PSR) on phagocytes is an active noninflammatory process which is associated with the down-regulation of proinflammatory mediators such as interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-8, IL-10, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor, tumor necrosis factor-α, leukotriene C4 and thromboxane B2, while the production of anti-inflammatory mediators (transforming growth factor [TGF]-β1, prostaglandin E2, and platelet-activating factor) is increased in human monocyte-derived macrophages.9,10 Therefore, abnormalities of apoptotic cell clearance may contribute to the pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory diseases.5,9

Tissue destruction in chronic pancreatitis is histopathologically associated with a large amount of infiltrating macrophages.11 In addition, infiltrates of cytotoxic cells are localized at the border of parenchyma and fibrosis, suggesting that cell-mediated cytotoxicity is involved in cell damage in this disease.12,13 Morphologically, cell damage and apoptosis in chronic pancreatitis are associated with up-regulation of pro-apoptotic genes,14 the FAS/FAS-l system,15 caspase-116 and p75NTR17 in atrophic acinar cells, proliferating cells of ductal origin and in acinar cells redifferentiating to form tubular structures. Apoptotic mechanisms in the margin regions of the parenchyma close to stromal fibroblasts may be responsible for increased acinar cell redifferentiation, death, and phagocytosis with replacement by stromal fibroblasts.18–20

Since apoptosis is active in chronic pancreatitis and large numbers of macrophages are present in CP tissue samples, we investigated whether the presence of macrophages is PS/PSR-mediated and whether PS/PSR interaction is a major component in apoptotic cell phagocytosis in CP.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients and Tissue Collection

Normal human pancreatic tissue samples were obtained through an organ donor program from 13 individuals (5 women and 8 men) who were free of any pancreatic disease. The median age of the organ donors was 42 years, with a range of 16 to 59 years. Chronic pancreatitis tissue samples were obtained from 29 patients (10 women, 19 men) undergoing a pancreatic head resection. In 24 of 29, patients chronic pancreatitis was due to alcohol abuse, 3 patients had idiopathic chronic pancreatitis, and in 2 patients the etiology was unknown. The median age of the chronic pancreatitis patients was 45 years, with a range from 27 to 57 years.

Freshly removed tissue samples were immediately fixed in paraformaldehyde solution for 12 to 24 hours and paraffin-embedded for immunohistochemistry. Concomitantly, tissue samples for RNA and protein extraction were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen in the operating room immediately upon surgical removal and maintained at −80°C until use. The studies were approved by the Human Subject Committee of the University of Bern, Switzerland, and Ethical Committee of the University of Heidelberg, Germany.

Probe Synthesis for Northern Blot Analysis

For Northern blot analysis, a 351-bp fragment of human PSR cDNA was amplified by RT-PCR using the following PSR primers: forward: 5′-GACTCTGGAGCGCCTAAAAA-3′; reverse: 5′-CCCTGAACTAAGGCATTCCA-3′. The purified PCR products were cloned into the pGEM-T vector (Promega Biotechnology, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The identity of the cDNA fragment was confirmed by sequence analysis using the dye terminator method (ABI 373A; Perkin Elmer, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). A 190-bp fragment of mouse 7S that cross-hybridizes with human 7S was used to verify equivalent RNA loading and transfer in Northern blot analysis.21 The probes were radiolabeled with [α-32P] dCTP (NEN Life Science Products AG, Geneva, Switzerland) using a random primer labeling system (Amersham, Pharmacia Biotech Europe GmbH, Dübendorf, Switzerland).

Northern Blot Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from all pancreatic tissue samples by the guanidinium isothiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction method.22 The procedures used have been described in detail previously.23 Briefly, following electrophoresis of total RNA in 1.2% agarose/1.8 M formaldehyde gels, the RNA was electrotransferred onto nylon membranes and cross-linked by UV irradiation. The filters were prehybridized for 5 hours at 42°C and hybridized for 20 hours at 42°C in the presence of the radio-labeled cDNA probe for PSR (106 cpm/mL). Afterward, blots were rinsed twice with 2 × SSC at 50°C, and washed twice with 0.2 × SSC/2% SDS at 55°C for 10 minutes.24,25 All blots were exposed at −80°C to Kodak XAR-5 films with Kodak intensifying screens, and the intensity of the radiographic bands was quantified by video image analysis using the Image-Pro plus software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD). To verify equivalent RNA loading on Northern blot membranes, filters were rehybridized with the 7S cDNA probe, as reported before.23

RNA Protection Assay (RPA)

Using an RNA protection assay (hAPO Multi-Probe Template Set; Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) the pro-apoptotic genes Bax, Bak, blk, and bcl-xs and the antiapoptotic genes bcl-xl, bfl-1, bcl-2, and mcl-1 were concomitantly analyzed. Fifteen micrograms of total RNA per sample were hybridized overnight at 42°C with α-32P-UTP-labeled riboprobes, and single-stranded RNA was subsequently digested with RNase-A/T1 according to the manufacturer's instructions. Yeast tRNA (10 μg) was used as a negative control. Samples were then subjected to denaturing gel electrophoresis on 6% polyacrylamide/8 M urea gels. Gels were dried and exposed to Kodak BioMax MS films at −80°C using intensifying screens. The intensity of the radiographic bands was quantified by densitometry. L32, a well-known housekeeping gene, was used to assess equivalent RNA loading. Densitometric analysis of chronic pancreatitis samples and normal controls was used to compare the mRNA expression levels of apoptosis-related genes. For statistical analysis, the samples were divided into 2 groups. The first group included normal and chronic pancreatitis samples with very low PSR mRNA expression levels; these were compared with the second group, with enhanced PSR mRNA expression levels. The Mann-Whitney U test and the Spearman correlation were used. P values of <0.05 were defined as significant.

Western Blot Analysis

Approximately 200 mg of frozen normal and chronic pancreatitis tissues from patients with elevated PSR m-RNA levels were powdered and thawed in an ice-cold suspension buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 100 mM NaCl) containing a proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). Tissues and cells were homogenized for 5 minutes in 1 mL of ice-cold suspension buffer and centrifuged (14,000 rpm, 30 minutes at 4°C). The supernatants were collected and the protein concentration was measured with the micro BCA protein assay (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL, USA). Forty micrograms of protein from each sample was diluted in sample buffer (250 mM Tris-HCl, 4% SDS, 10% glycerol, 0.006% bromphenol blue and 2% β-mercaptoethanol), boiled for 5 minutes, cooled on ice for 5 minutes, and size-fractionated on 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Gels were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, and the membranes were incubated in blocking solution (5% nonfat milk in 20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20 [TBS-T]), followed by incubation with monoclonal mouse IgG2b antihuman PSR antibody (Cascade Bioscience, Winchester, MA; 1:1000 dilution) in blocking solution for 12 hours at 4°C. The membranes were washed with TBS-T and incubated with a sheep antimouse IgG horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibody (Amersham Biosciences Europe GmbH, Freiburg, Germany; 1:5000 dilution). Antibody detection was performed with the enhanced chemoluminescence Western blot detection system (Amersham Biosciences Europe GmbH, Freiburg, Germany). Signals were quantified by video image analysis using the Image-Pro plus software (Media Cybernetics).

Immunohistochemistry

Ten normal pancreatic and 20 chronic pancreatitis sections were analyzed. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed with the mouse EnVision 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AEC) System (DAKO Diagnostics AG, Zürich, Switzerland). Briefly, consecutive 3–5 μm paraffin-embedded tissue sections were dewaxed and rehydrated. Antigen retrieval was achieved by boiling the sections in 5% urea Tris-HCl buffer, pH 9.5, in an 850-watt microwave oven for 8 minutes, followed by 2 similar treatments at 400 watt for 5 minutes each. Afterward, the sections were washed in Tris-buffered saline pH 7.4 (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6 and 150 mM NaCl) and incubated at room temperature for 5 minutes with peroxidase blocking solution. The sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary monoclonal mouse IgG2b antihuman PSR antibody (Cascade Bioscience; 1:100 dilution) and with the M30 CytoDEATH monoclonal mouse IgG2b antibody (Roche Diagnostics GmbH; detection of specific caspase cleavage site within cytokeratin 18 to determine very early apoptosis in cells and tissue, dilution according to the manufacturer's recommendations), both diluted in 5% normal goat serum and 0.5% bovine serum albumin. After incubation with the peroxidase-labeled polymer conjugated to goat antimouse immunoglobulins for 30 minutes, the sections were incubated with the AEC Substrate-Chromogen solution for 20 minutes, followed by counterstaining with hematoxylin. To ensure specificity of the primary antibody, consecutive tissue sections were incubated with mouse IgG2b as a negative control antibody (DAKO Diagnostics AG) and in the absence of the primary antibody with normal goat serum. In these cases no immunostaining was detected.

Apoptosis Detection by TUNEL Assay

The TUNEL assay was performed for in situ apoptotic cell death detection according to the manufacturer's instructions with some modification (TUNEL alkaline phosphatase [AP], TUNEL Enzyme, TUNEL reaction mixture; Roche Diagnostics). Briefly, paraffin sections were deparaffinized in xylene followed by decreasing ethanol concentrations and distilled water. The slides were then treated with proteinase K (30 μg/mL) in 10 mM Tris pH 8.0 for 40 minutes at 37°C. Afterward, 50 μL of TUNEL reaction mixture was added to each slide and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour in a humid chamber. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline, 50 μL of converter-AP was added on each slide, and the slides were incubated at 37°C for 45 minutes. For color reaction, a 50-μL substrate solution (Fast Red/Naphtol; Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO) was used. After incubation for 15 minutes at room temperature, slight counterstaining of the slides with hematoxylin was performed. For negative control, the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase enzyme was omitted. For analysis, the TUNEL signals and the total cell number in 10 randomly selected areas of all sections (2 mm2 in total) in normal and chronic pancreatitis samples were counted.

Statistical Analysis

The chronic pancreatitis samples were grouped according to their PSR mRNA expression levels. Samples exhibiting enhanced PSR mRNA expression levels in comparison with the normal controls were grouped as “positive” and samples with PSR mRNA expression levels comparable to normal controls were grouped as “negative.”

To evaluate whether a relationship existed between the PSR mRNA expression levels and clinical parameters, the following clinical criteria were registered: a) pain intensity (rank 0, no pain; rank 1, mild pain; rank 2, moderate pain; rank 3, severe pain), b) pain frequency (rank 0, no pain; rank 1, monthly pain; rank 2, weekly pain; rank 3, daily pain) and c) glucose tolerance (rank 0, normal; rank 1, latent diabetes mellitus; rank 2, manifest diabetes mellitus). Data are expressed as median and range. For statistical comparison, the Mann-Whitney U test and the Spearman correlation were used. P values of <0.05 were defined as significant. The SPSS 8.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

PSR mRNA Expression in the Normal Pancreas and Chronic Pancreatitis

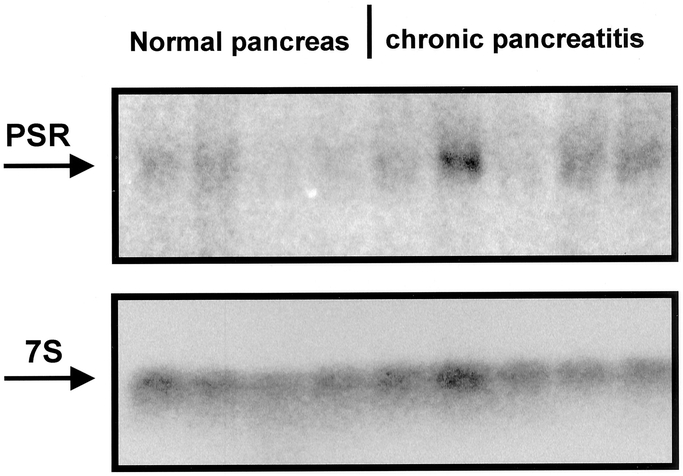

Thirteen normal and 29 chronic pancreatitis samples were analyzed by Northern blot analysis to detect PSR mRNA expression (Fig. 1). The transcript size of PSR mRNA in pancreatic tissue samples was approximately 2.0 kb, which is in accordance with previous reports, and no aberrant mRNA moieties were found.3 In the normal pancreas, moderate levels of PSR were detectable only in 2 samples (15%), whereas in the other 10 samples the expression levels were very faint or absent. Seventeen of 29 (59%) chronic pancreatitis tissue samples exhibited faint PSR mRNA expression comparable to that in the normal controls. In contrast, 12 of 29 (41%) chronic pancreatitis tissue samples showed markedly increased PSR mRNA expression levels in comparison with the normal controls. Quantification of the mRNA signals revealed that PSR mRNA levels were 140% higher in chronic pancreatitis tissues when all chronic pancreatitis samples were compared with the normal controls (P = 0.46). However, when only chronic pancreatitis samples with increased expression were evaluated, the increase was 220% (P < 0.001) in comparison with normal controls.

FIGURE 1. Northern blot analysis of PSR mRNA in the normal pancreas (normal) and chronic pancreatitis (CP). 7S hybridization was used to verify equal RNA loading and transfer.

Immunohistochemistry

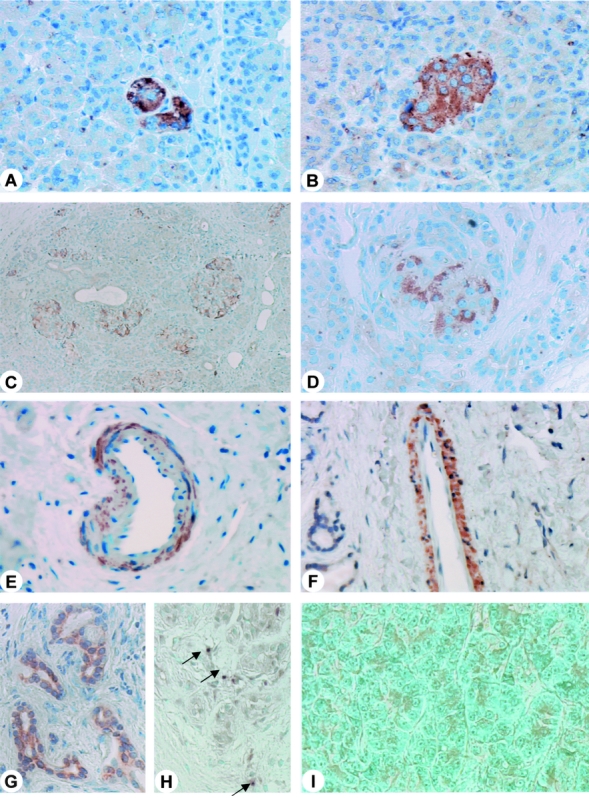

In the normal pancreas, PSR immunoreactivity was faintly present in islets and in a few acinar cells (Figs. 2A, B). In chronic pancreatitis sections, islets surrounded by exocrine parenchyma (Fig. 2C) or by stromal fibroblasts (Fig. 2D) and macrophages exhibited PSR immunoreactivity (Fig. 2C, D). Furthermore, strong basal staining was present in acinar cells, as well as in tubular complexes. In addition, in chronic pancreatitis samples the muscular layer of some arteries (Fig. 2E) and lymphatic vessels (Fig. 2F) exhibited PSR immunoreactivity which was not seen in normal controls. However, when CytoDEATH M30 staining was performed in consecutive tissue sections, only small degenerating ducts and acinar cells dedifferentiating into tubular complexes (Fig. 2G) revealed positive immunoreactivity.

FIGURE 2. PSR immunohistochemistry in the normal pancreas (A, B) and in chronic pancreatitis sections (C-F). In the normal pancreas, PSR immunoreactivity was present in some acinar cells (A) and islets (B). In chronic pancreatitis (C-F), cytoplasmic PSR immunoreactivity was present in a lobular pattern of acinar cells (C) and in islets (D). In some chronic pancreatitis samples, blood vessels (E) and lymphatic vessels (F) exhibited PSR immunoreactivity as well. CytoDeath M30 immunostaining was absent in the normal pancreas (G). In contrast, in chronic pancreatitis Cyto-Death M30 immunoreactivity was strongly present in acinar cells adjacent to islets (H) or fibroblasts (I). C, H, Original magnification × 50; A, original magnification × 100; B, D-G, I, original magnification × 200.

Western Blot Analysis of PSR in the Normal Pancreas and Chronic Pancreatitis

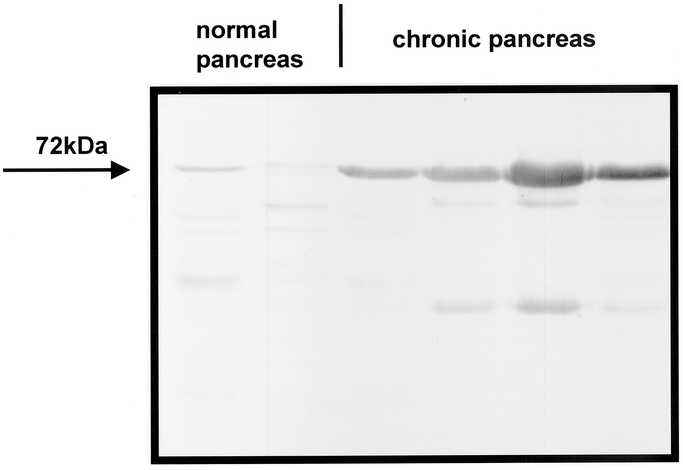

Western blot analysis of PSR was performed in normal human pancreas and chronic pancreatitis samples with high PSR mRNA expression to quantify differences in protein levels. Incubation with the mouse monoclonal antihuman PSR antibody revealed a strong 72-kDa PSR protein band in all chronic pancreatitis tissue samples, whereas in the normal controls only a weak signal was present (Fig. 3). Quantification of the signals by video image analysis revealed that the PSR protein levels were 9.4-fold increased in chronic pancreatitis samples with increased PSR m-RNA expression compared with the normal controls (P < 0.008).

FIGURE 3. Western blot analysis of PSR in the normal pancreas and in chronic pancreatitis. A 72-kDa PSR glycosylated protein band was detectable in the pancreatic tissues, with much stronger intensity in chronic pancreatitis compared with normal controls.

Apoptosis Detection by TUNEL Assay

In the normal pancreas, TUNEL staining was occasionally present in a few acinar cell nuclei. In contrast, in chronic pancreatitis samples increased TUNEL staining was found mainly in acinar cell nuclei. TUNEL staining was detected in acinar cells which were located at the margins of acinar lobules next to fibrosis or islets, and in regions where the acinar cells were surrounded by stromal fibroblasts (Figs. 2H, I). Quantification of TUNEL staining signals revealed a 6.2-fold increase in all chronic pancreatitis samples (with and without increased PSR m-RNA expression) compared with normal controls (Mann-Whitney U test, P < 0.005).

RNA Protection Assay

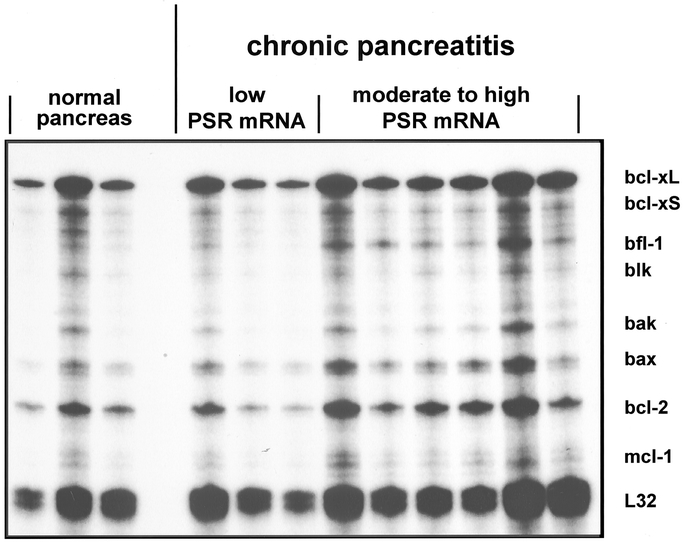

By RNA protection assay the expression levels of pro-apoptotic (Bax, Bak, blk, bcl-xs) and antiapoptotic (bcl-xl, bfl-1, bcl-2, mcl-1) genes were analyzed and compared with the expression levels of PSR (Fig. 4). Chronic pancreatitis samples with increased PSR mRNA levels revealed increased expression of Bax (2.5-fold increase, P < 0.04) and Bak (1.8-fold increase, P < 0.05), whereas bcl-xS and blk were not altered. Furthermore, chronic pancreatitis samples with increased PSR mRNA levels also exhibited increased expression of bfl-1 (3-fold increase, P < 0.04) and bcl-2 (1.7-fold increase, P < 0.04), whereas bcl-xL and mcl-1 were unchanged compared with normal controls. In contrast, in chronic pancreatitis samples in which PSR mRNA was not increased, the expression of pro-apoptotic and antiapoptotic genes was comparable with expression in normal controls.

FIGURE 4. RNA protection assay of apoptosis-related genes (bcl-xL, bcl-xS, bfl-1, blk, bak, bax, bcl-2, and mcl-1) in normal pancreas and chronic pancreatitis samples with low and moderate to high PSR mRNA expression levels. L32 is a housekeeping gene which was used to verify equal RNA loading and transfer.

Furthermore, there was a significant relationship in chronic pancreatitis samples with increased PSR mRNA levels (Spearman test) between PSR mRNA and bcl-2 (P < 0.05) and bfl-1 (P < 0.05) mRNA expression levels (data not shown).

Relationship of PSR mRNA Expression With Clinical and Histopathological Data

The case histories of 29 patients with chronic pancreatitis were analyzed for pain intensity, pain frequency, and/or glucose tolerance abnormality or diabetes mellitus. No relationship between these clinical parameters and PSR-mRNA expression levels was found. In addition, there was no correlation between PSR mRNA expression and the presumed etiology of chronic pancreatitis.

DISCUSSION

Apoptosis plays a crucial role in the destruction, remodeling, and repair process in chronic pancreatitis, but the exact mechanisms and factors which are involved in this process are not well defined.14 The loss of pancreatic parenchyma is accompanied by infiltrating leukocytes, and there is strong evidence that these cells are directly involved in tissue destruction.11–13 Besides high numbers of T-lymphocytes, about one third of these inflammatory cells consist of macrophages.12

When the expression of PS receptor was analyzed in chronic pancreatitis tissue, its localization was mainly expected on the surface of phagocytizing cells (eg, macrophages) as reported in other disorders before. Surprisingly, in addition to its presence on few macrophages, PS receptor was predominantly expressed on the remaining pancreatic acinar, ductal, and islet cells.

The PS receptor is localized on the surface of macrophages3,26,27 and other phagocytes,28 and exclusively there its crucial role in apoptosis has been clarified. Since a potential function of this receptor on the surface of cells other than phagocytes has not been defined, in the present study the involvement of the PS receptor in apoptosis in the normal pancreas and in chronic pancreatitis was analyzed.

PSR mRNA expression and protein were significantly enhanced in 41% of the chronic pancreatitis tissue samples. In these tissue samples, RPA revealed significant overexpression of bfl-1/bcl-2 antiapoptotic and bax/bak proapoptotic genes, pointing to an involvement of the nonmacrophage-related PS receptors in apoptosis. Immunohistochemistry localized PSR in almost all islets of the chronic pancreatitis tissue samples, to small ducts and to degenerating acinar cells. Interestingly, the distribution pattern of PSR in chronic pancreatitis corresponded closely to the patterns of other apoptosis-related genes such as FAS/FASL and caspase-1. The Fas/Fas ligand system is involved in the onset of inflammation and apoptosis in various inflammatory diseases, in organs including the pancreas.29,30 In an experimental chronic pancreatitis model, Fas/FasL-mRNA was detected in the cytoplasm of acinar cells, ductal cells, and lymphocytes and was already expressed when the pancreas still appeared to be normal by histologic analysis, suggesting that the Fas/FasL system is already involved early in acinar cell apoptosis and the progression of chronic pancreatitis.15 This shows that apoptotic processes are involved very early in the etiology and progression of chronic pancreatitis and furthermore explains that no correlation was present between PSR mRNA levels and clinical parameters in our analysis.

Furthermore, a recent study showed that caspase-1, another apoptotic mediator in chronic pancreatitis, is expressed in atrophic acinar cells, in proliferating cells of ductal origin, and in acinar cells redifferentiating to form tubular structures. This suggests 2 functions: the induction of apoptosis in atrophic acinar cells and a specific role in the process of dedifferentiation of acinar cells into tubular structures.16 Immunohistochemical analysis of caspase cleaved formalin-resistant epitope of human cytokeratin 18, a cytoskeletal protein expressed in the pancreas,31 also revealed immunoreactivity in acinar cells redifferentiating to tubular structures and in some acinar cells near the adjacent fibrotic stromal tissue, suggesting that these parenchymal elements are eliminated via activation of apoptosis.16

TUNEL in situ apoptosis staining, which measures and quantifies cell death and apoptosis by labeling and detection of DNA strand breaks in individual cells, showed specific nuclear staining of acinar cells characteristic for apoptosis in chronic pancreatitis samples. Quantification of the staining signals revealed a significant increase in chronic pancreatitis samples. Interestingly, as shown before in caspases, apoptotic acinar cells were often surrounded by stromal fibroblasts or were located mainly at the margin of acinar lobules next to the areas of fibrosis or islets.

A histologic characteristic of chronic pancreatitis is fibrosis development. Acinar cells die or redifferentiate, whereas the islets remain relatively unaffected.32 Damage of parenchymal structures and therefore functional loss occurs more often in the exocrine system than in the endocrine system.33 Strong pancreatic islet PSR m-RNA expression and immunoreactivity, together with a significant up-regulation of bfl-1 and bcl-2 antiapoptotic genes34,35 and a pattern of M30 cyto death staining, which omits islet cells, alludes to a protective function of this gene in the apoptotic process in chronic pancreatitis, where pancreatic islet cells are less involved. However, the exact biologic function of the PS receptor on ductal, acinar, and islet cells in chronic pancreatitis is not clear. It has been well demonstrated that binding of PS to its receptor on macrophages stimulates the secretion of TGF-β from the phagocytes as an active immunosuppressive process. Whether binding to the nonmacrophage PS receptors occurs and whether this leads to secretion of the profibrinogenic factor TGF-β in relevant amounts will be a focus of further studies.

However, only 41% of the analyzed chronic pancreatitis tissues showed significant overexpression of PSR mRNA. This conforms to our understanding the concept that activation of apoptosis is one part of the continuously ongoing process of tissue destruction and remodeling in chronic pancreatitis. As reported for other molecular mechanisms which are involved in the pathogenesis of chronic pancreatitis,36 phosphatidylserine receptor–associated apoptosis seems to be alternately activated and deactivated, depending whether tissue destruction or tissue remodeling occurs.

In summary, we showed for the first time the presence and a marked up-regulation of the PS receptor in chronic pancreatitis on the surface of pancreatic cells other than macrophages. The distribution pattern of PSR corresponds widely to genes involved in apoptosis, and this alludes to a still unknown function of this receptor in apoptosis. The impact of this finding is still unclear. It supports the theory that apoptotic processes play a major role in the destructive process of chronic pancreatitis but more interestingly suggests that PSR has a wider spectrum of functions than just serving as a mediator of apoptotic cell engulfment by macrophages.

Footnotes

The first two authors contributed equally to the preparation of the manuscript.

Address correspondence to: Helmut Friess, MD, Department of General Surgery, University of Heidelberg, Im Neuenheimer Feld 110, D-69120 Heidelberg, Germany. E-mail: helmut_friess@med.uni-heidelberg.de.

REFERENCES

- 1.Somersan S, Bhardwaj N. Tethering and tickling: a new role for the phosphatidylserine receptor. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:501–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ran S, Downes A, Thorpe PE. Increased exposure of anionic phospholipids on the surface of tumor blood vessels. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6132–6140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fadok VA, Voelker DR, Campbell PA, et al. Exposure of phosphatidylserine on the surface of apoptotic lymphocytes triggers specific recognition and removal by macrophages. J Immunol. 1992;148:2207–2216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Frasch SC, et al. The role of phosphatidylserine in recognition of apoptotic cells by phagocytes. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:551–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fadok VA, McDonald PP, Bratton DL, et al. Regulation of macrophage cytokine production by phagocytosis of apoptotic and post-apoptotic cells. Biochem Soc Trans. 1998;26:653–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fadok VA, de Cathelineau A, Daleke DL, et al. Loss of phospholipid asymmetry and surface exposure of phosphatidylserine is required for phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages and fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1071–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin SJ, Reutelingsperger CP, McGahon AJ, et al. Early redistribution of plasma membrane phosphatidylserine is a general feature of apoptosis regardless of the initiating stimulus: inhibition by overexpression of Bcl-2 and Abl. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1545–1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffmann PR, deCathelineau AM, Ogden CA, et al. Phosphatidylserine (PS) induces PS receptor-mediated macropinocytosis and promotes clearance of apoptotic cells. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:649–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Konowal A, et al. Macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells in vitro inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production through autocrine/paracrine mechanisms involving TGF-beta, PGE2, and PAF. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:890–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDonald PP, Fadok VA, Bratton D, et al. Transcriptional and translational regulation of inflammatory mediator production by endogenous TGF-beta in macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells. J Immunol. 1999;163:6164–6172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goecke H, Forssmann U, Uguccioni M, et al. Macrophages infiltrating the tissue in chronic pancreatitis express the chemokine receptor CCR5. Surgery. 2000;128:806–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emmrich J, Weber I, Nausch M, et al. Immunohistochemical characterization of the pancreatic cellular infiltrate in normal pancreas, chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma. Digestion. 1998;59:192–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunger RE, Müller C, Z'graggen K, et al. Cytotoxic cells are activated in cellular infiltrates of alcoholic chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1656–1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graber HU, Friess H, Zimmermann A, et al. Bak expression and cell death occur in peritumorous tissue but not in pancreatic cancer cells. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999;3:74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su SB, Motoo Y, Xie MJ, et al. Apoptosis in rat spontaneous chronic pancreatis: role of the Fas and Fas ligand system. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:166–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramadani M, Yang Y, Gansauge F, et al. Overexpression of caspase-1 (interleukin-1beta converting enzyme) in chronic pancreatitis and its participation in apoptosis and proliferation. Pancreas. 2001;22:383–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nilsson AS, Fainzilber M, Falck P, et al. Neurotrophin-7: a novel member of the neurotrophin family from the zebrafish. FEBS Lett. 1998;424:285–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bockman DE, Büchler MW, Malfertheiner P, et al. Analysis of nerves in chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1988;94:1459–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friess H, Müller M, Ebert M, et al. [Chronic pancreatitis with inflammatory enlargement of the pancreatic head]. Zentralbl Chir. 1995;120:292–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weihe E, Nohr D, Müller S, et al. The tachykinin neuroimmune connection in inflammatory pain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;632:283–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.di Mola FF, Friess H, Scheuren A, et al. Transforming growth factor-betas and their signaling receptors are coexpressed in Crohn's disease. Ann Surg. 1999;229:67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friess H, Lu Z, Graber HU, et al. Bax, but not bcl-2, influences the prognosis of human pancreatic cancer. Gut. 1998;43:414–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friess H, Yamanaka Y, Büchler MW, et al. A subgroup of patients with chronic pancreatitis overexpress the c-erb B-2 protooncogene. Ann Surg. 1994;220:183–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamanaka Y, Friess H, Büchler MW, et al. Synthesis and expression of transforming growth factor beta-1, beta-2, and beta-3 in the endocrine and exocrine pancreas. Diabetes. 1993;42:746–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fadok VA, Savill JS, Haslett C, et al. Different populations of macrophages use either the vitronectin receptor or the phosphatidylserine receptor to recognize and remove apoptotic cells. J Immunol. 1992;149:4029–4035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fadok VA, Xue D, Henson P. If phosphatidylserine is the death knell, a new phosphatidylserine-specific receptor is the bellringer. Cell Death Differ. 2001;8:582–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De SR, Ajmone-Cat MA, Nicolini A, et al. Expression of phosphatidylserine receptor and down-regulation of pro-inflammatory molecule production by its natural ligand in rat microglial cultures. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61:237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bateman AC, Turner SM, Thomas KS, et al. Apoptosis and proliferation of acinar and islet cells in chronic pancreatitis: evidence for differential cell loss mediating preservation of islet function. Gut. 2002;50:542–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernstorff WV, Glickman JN, Odze RD, et al. Fas (CD95/APO-1) and Fas ligand expression in normal pancreas and pancreatic tumors: implications for immune privilege and immune escape. Cancer. 2002;94:2552–2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toivola DM, Baribault H, Magin T, et al. Simple epithelial keratins are dispensable for cytoprotection in two pancreatitis models. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;279:G1343–G1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sarles H. Chronic pancreatitis and diabetes. Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;6:745–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cavallini G, Bovo P, Zamboni M, et al. Exocrine and endocrine functional reserve in the course of chronic pancreatitis as studied by maximal stimulation tests. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:93–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mizuno N, Yoshitomi H, Ishida H, et al. Altered bcl-2 and bax expression and intracellular Ca2+ signaling in apoptosis of pancreatic cells and the impairment of glucose-induced insulin secretion. Endocrinology. 1998;139:1429–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang B, Johnson TS, Thomas GL, et al. Expression of apoptosis-related genes and proteins in experimental chronic renal scarring. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:275–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kashiwagi M, Friess H, Uhl W, et al. Phospholipase A2 isoforms are altered in chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1998;227:220–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]