Abstract

Cyclin T1 (CycT1), a component of positive-transcription-elongation factor-b (P-TEFb), is an essential cofactor for transcriptional activation by lentivirus Tat proteins. It is thought that low CycT1 expression levels restrict human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) expression levels and replication in resting CD4+ lymphocytes. In this study, we undertook a functional analysis of the cycT1 promoter to determine which, if any, promoter elements might be responsible for cellular activation state-dependent CycT1 expression. The cycT1 gene contains a complex promoter that exhibits an extreme degree of functional redundancy: five nonoverlapping fragments were found to exhibit significant promoter activity in immortalized cell lines, and these elements could interact in a synergistic or redundant manner to mediate cycT1 transcription. Reporter gene expression, mediated by the cycT1 promoter, was detectable in unstimulated transfected primary lymphocytes and multiple sites within the promoter could serve to initiate transcription. While utilization of these start sites was significantly altered by the application of exogenous stimuli to primary lymphocytes and two distinct promoter elements exhibited enhanced activity in the presence of phorbol ester, overall cycT1 transcription was only modestly enhanced in response to cell activation. These observations prompted a reexamination of CycT1 protein expression in primary lymphocytes. In fact, steady-state CycT1 expression is only slightly lower in unstimulated lymphocytes compared to phorbol ester-treated cells or a panel of immortalized cell lines. Importantly, CycT1 is expressed at sufficient levels in unstimulated primary cells to support robust Tat activity. These results strongly suggest that CycT1 expression levels in unstimulated primary lymphocytes do not profoundly limit HIV-1 gene expression or provide an adequate mechanistic explanation for proviral latency in vivo.

The human immunodeficiency viruses (HIVs) and related lentiviruses from simian, equine, and bovine species each encode a transcriptional transactivator (Tat) that dramatically activates transcription by recruiting a form of positive transcription elongation factor-b (P-TEFb) to the viral promoter (2, 8–11, 21, 22, 28, 52). P-TEFb is largely responsible for the hyperphosphorylation of the C-terminal domain (CTD) of the RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) large subunit (38, 44), an event associated with the transition of the transcription complex to a processive form (15, 38). Indeed, P-TEFb-induced CTD phosphorylation overcomes the inhibitory effects on transcription elongation mediated by negative elongation factors (NELF) and DSIF (DRB sensitivity inducing factor) (50, 51, 55). The minimal form of P-TEFb includes either cyclin T1 (CycT1), cyclin T2A (CycT2A), cyclin T2B (CycT2B), or cyclin K, which are regulatory subunits of distinct forms of the P-TEFb complex (20, 43). While each of these cyclins can form a complex with, and thereby activate, the catalytic P-TEFb subunit, CDK9, the majority of CDK9 present in HeLa nuclear extracts is associated with the CycT1 containing form of P-TEFb (43).

The lentiviral Tat proteins represent a unique family of transcriptional activators in that they function via promoter-proximal RNA target sequences, termed TAR elements (17), and activate transcription predominantly at the level of elongation (16, 31, 33, 37). Moreover, CycT1, but not CycT2A or CycT2B has been shown to be a functional partner for the lentiviral Tat proteins (7, 41, 53). In fact, Tat proteins bind directly to CycT1 and the resulting Tat-P-TEFb complex subsequently binds to the viral TAR element (10, 52, 53). The Tat/TAR axis thus serves to actively recruit P-TEFb to the vicinity of recently initiated RNAPII transcription complexes. With the exception of bovine immunodeficiency virus Tat, which can bind with high affinity to a cognate TAR element in the absence of cellular cofactors (5, 11), CycT1, and possibly CDK9, contribute to the RNA binding affinity and specificity of the Tat-P-TEFb complex (2, 8–10, 19, 22–24, 52, 53). The observation that Tat-mediated transcriptional activation can be recapitulated simply by tethering CycT1 or CDK9 to a promoter-proximal RNA or DNA target argues that P-TEFb recruitment is the sole mechanism by which Tat proteins activate lentiviral gene expression (10, 21, 36).

HIV-1 fails to replicate in unstimulated CD4+ lymphocytes. While blocks at reverse transcription and integration have been shown to contribute to this phenomenon (12, 47, 56), it is also apparent that HIV-1 gene expression is significantly attenuated in resting cells. Indeed, significant numbers of integrated, but transcriptionally latent, proviruses exist in the resting peripheral blood CD4+ T-cell population in infected individuals. This “latent pool” is a significant obstacle to the eradication of HIV-1 from infected individuals by chemotherapy (14, 18). The mechanisms that govern whether a provirus is latent or transcriptionally active remain only partly understood, but it is clear that HIV-1 expression is modulated by the cellular activation state (1, 3, 13, 14, 29, 32, 35, 39). Relevant cellular factors that are functionally upregulated upon T-cell activation include NF-κB, NFAT, and CycT1. In the latter case, previous work has indicated that CycT1 is expressed at only low levels in unstimulated primary lymphocytes but is responsive to stimulation by phorbol ester- or lectin-mediated cellular activation (25, 26). Therefore, it has been suggested that a relative lack of CycT1 expression might contribute to the failure of HIV-1 to replicate in unstimulated primary lymphocytes and, in part, explain the lack of proviral transcription in latently infected cells in vivo (25, 26, 44, 48). Because the CycT1 promoter is constitutively active and not significantly responsive to exogenous stimuli in immortalized cell lines (34), it is unclear whether activation induced CycT1 expression in primary lymphocytes is due to transcriptional or posttranscriptional mechanisms.

In this study, we performed a functional analysis of the cycT1 promoter to investigate how CycT1 expression is regulated at the transcriptional level in immortalized cell lines and in response to stimuli in primary lymphocytes. This analysis reveals that the cycT1 promoter contains multiple elements that contribute to constitutive activity, both in a variety of cell lines and in primary cells. Importantly, although the cycT1 promoter is modestly upregulated and exhibits changes in the utilization of transcription initiation sites in response to exogenous stimuli in primary lymphocytes, the basal level of CycT1 expression in unstimulated cells is sufficient to support robust Tat activity. Taken together, these observations suggest that limited Tat function, resulting from only low levels of CycT1 expression, does not provide an adequate mechanistic explanation for the establishment and maintenance of latent proviruses in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning and analysis of the cycT1 promoter.

Genomic DNA sequences corresponding to the 5′ region of the cycT1 coding sequence were cloned by using the GenomeWalker Kit (Clontech). The first PCR was performed with the AP1 primer (Clontech) and the cycT1 specific oligonucleotide T1GP1 (5′-TTTGTTGTTGTTCTTCCTCTCTCCCTC-3′). This product was used as the template for a nested amplification with the AP2 and T1GP2 (5′-CTCCATAGTGCTTCAACCAGAAGGCAG-3′) primers. Two fragments of 2,215 and 2,375 nucleotides were obtained and inserted into pBluescript SK (Stratagene), and four independent clones were sequenced. The identification of putative transcription factor binding sites was done by using the programs MacVector 6.5.1 (Oxford Molecular) and TESS (Transcription Element Search Software [http://www.cbil.upenn.edu/tess/index.html]). Only sequences that were identical to the consensus sequence for transcription factors in either database were considered. The mouse cycT1 promoter was identified by searching the High Throughput Genomic Sequences database by using the BLAST program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/).

Plasmid construction.

An NcoI restriction site underlying the translation initiation codon of cyclin T1 gene (hereafter referred to as position +1) was used to insert the 2,051-nucleotide genomic fragment in the SmaI and NcoI sites of the pGL3-basic vector (Promega). Progressive 5′-to-3′ deletions of the genomic sequence were generated by PCR with the appropriate oligonucleotides. The 3′-to-5′ series of deletion mutants were similarly generated by PCR and inserted into the PstI restriction site located at position −31 of the CycT1 promoter. The pcTat and pBC12/CMV/lacZ plasmids have been previously described (9, 49) and pHIV/luc was constructed by inserting an XhoI -HindIII fragment comprising the 3′ long terminal repeat (LTR) from pIIIB into the XhoI and HindIII sites of pGL3-basic.

Primer extension analysis.

Total RNA was purified from immortalized cell lines and primary lymphocytes using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies). T-cell (Jurkat and MT4) monocytic (THP1 and U937), epithelial (HeLa and 293T), and fibroblast (HOS) cell lines were included in these experiments. The T1GP1 oligonucleotide was labeled by using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Life Technologies), and 2 × 105 cpm were hybridized with 10 μg of RNA at 72°C for 10 min. The reverse transcription reaction was done at 42°C for 1 h with SuperScript RNase H− Reverse Transcriptase (Life Technologies). The transcribed products were phenol-chloroform extracted, ethanol precipitated, and separated by electrophoresis on denaturing 6% acrylamide gels with 32P-labeled MspI-digested pBR322 as a size marker.

RNase protection assays.

A 206-nucleotide fragment of cycT1 cDNA was amplified by PCR and inserted into the HindIII and XhoI sites of pBluescript SK. This plasmid was linearized with HindIII and transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase in the presence of [32P]CTP to generate a 232-nucleotide probe. Ten micrograms of total RNA, extracted from unstimulated and phorbol myristate acetate (PMA)-treated primary lymphocytes, was subjected to RNase protection analysis by using this probe and a kit (RPA III; Ambion) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Protected fragments were separated on a 6% acrylamide gel, detected by autoradiography, and quantitated by densitometry.

Cell transfection assays.

To determine the transcriptional activity of cycT1 promoter constructs, 293T cells were transfected with 200 ng of a luciferase reporter plasmid and 100 ng of pBC12/CMV/lacZ using Lipofectamine Plus (Life Technologies), and the enzymatic activities were measured 48 h later by using the Luciferase Assay System (Promega) and Galacto-Star (Tropix) kits. Alternatively, Jurkat E6 and U937 cells were transfected by electroporation at 280 V and 1,500 μF (Jurkat) and at 300 V and 1,500 μF (U937). In these cases, 5 × 106 cells were transfected with 5 μg of the luciferase reporter plasmids and 2.5 μg of pBC12/CMV/lacZ, and the luciferase and β-galactosidase activities in cell lysates were measured 24 h after transfection. Primary lymphocytes from healthy donors were isolated by Ficoll gradient centrifugation and resuspended in RPMI supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. For analysis of cycT1 promoter activity, 107 cells were mixed with 10 μg of luciferase reporter plasmids and 5 μg of pBC12/CMV/lacZ. Alternatively, to measure Tat function in primary lymphocytes, cells were mixed with 10 μg of pHIV/luc, 10 μg of pcTat, and 5 μg of pBC12/CMV/lacZ. Cells were electroporated at 320 V and 1,500 μF, and the luciferase and β-galactosidase activities in cell lysates were measured 24 h later. PMA (Sigma) was added at 25 ng/ml to some cultures 2 h after electroporation.

Western blot analysis.

Protein extracts were prepared by lysing cells in a buffer containing 125 mM Tris (pH 6.8), 10% glycerol, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.1 M dithiothreitol, and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Immediately after cell lysis, the samples were boiled for 5 min and 10 μg of protein extract from cell lines or primary lymphocytes was separated in a 7% polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane that was sequentially probed with the C-20 anti-goat polyclonal antibody raised against cyclin T1 (Santa Cruz) diluted 1/500 and with an anti-goat peroxidase antibody (Roche). Thereafter, blots were developed by using chemiluminescent substrate reagents (Pierce). In some experiments, blots were also probed with an anti-ERK-1 monoclonal antibody to confirm equivalent loading. In addition, when primary lymphocytes were analyzed, aliquots of cells were subjected to fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis by using an anti-CD69 monoclonal antibody, prior to lysis, to confirm the resting and activated states of the unstimulated and PMA-treated cells, respectively.

RESULTS

Definition of functional cycT1 promoter sequences.

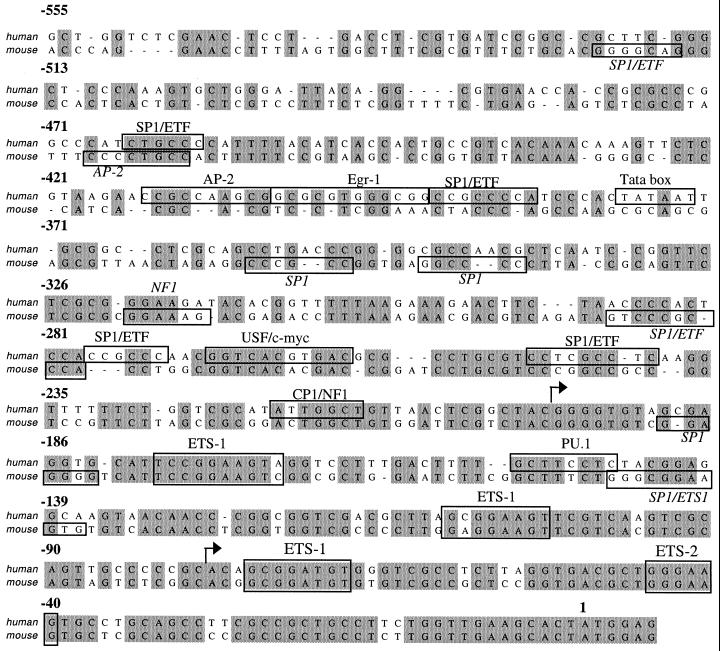

To define promoter sequences that are functionally important in the regulated expression of CycT1, 2,051 nucleotides situated 5′ to the cycT1 translation start site were amplified from human genomic DNA. Subsequent functional analysis determined the entire promoter activity resides in the 545 nucleotides 5′ to the translation initiation site, which hereafter is referred to as position +1. The 545 nucleotides that comprise the full cycT1 promoter are shown in Fig. 1, aligned with the corresponding region of mouse genomic DNA whose sequence became available during the course of these studies. The cycT1 promoter contains a wide array of sequence motifs that could, potentially, serve as binding sites for a variety of transcription factors. It is notable that the presence of some putative transcription factor binding sites are conserved in both species, most notably those for Sp1 and the Ets family of transcription factors. In contrast, other putative sites are not conserved, particularly those present at more distal positions to the translation start site. A functional role for these putative binding sites in regulating cycT1 expression is, at present, speculative and has not been determined by functional assays.

FIG. 1.

Conservation and divergence in putative transcription factor binding sites present in the human and murine cycT1 promoters. The sequence of the 545-nucleotide human cycT1 promoter is shown, aligned with the corresponding murine genomic sequence. Transcription factor binding sites, predicted by using MacVector (Oxford Molecular) or Transcription Element Search Software (TESS), are indicated by boxes. Arrows indicate major discrete sites of transcription initiation, as defined in Fig. 5.

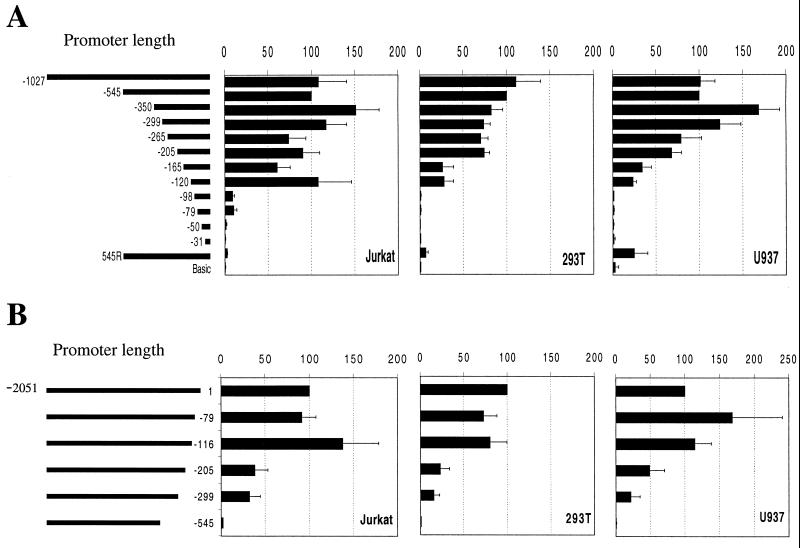

Therefore, to perform a preliminary functional analysis of the cycT1 promoter, a 2,051-nucleotide DNA sequence located immediately 5′ to the cycT1 translation initiation site was inserted into a luciferase reporter vector. Transfection of this construct resulted in readily detectable luciferase expression in a variety of cell lines that was ca. 100-fold greater that that observed upon transfection of the control vector (Fig. 2), indicating that this sequence indeed contains a functional promoter. Subsequently, a series of 5′ and 3′ deletion mutants were constructed and tested in three cell lines. Specifically, 293T (fibroblast), Jurkat (CD4 + T-cell), and U937 (promonocyte) cell lines were included in this analysis in an attempt to uncover any potential tissue-specific functional elements in the cycT1 promoter. In addition, the latter two cell lines were included because they represent functional target cells for HIV-1 infection and respond to extracellular stimuli that might influence promoter activity. The results of these experiments are shown in Fig. 2. This analysis clearly demonstrated that for each cell line the entire promoter activity of the cloned 2,051-nucleotide fragment resides in the 545 nucleotides 5′ to the cycT1 coding sequence. Specifically, a promoter containing these 545 nucleotides was at least as active in each cell line as was a promoter containing additional 5′ sequences up to and including the entire 2,051-nucleotide sequence (data not shown). Conversely, removal of these 545 nucleotides from the 2,051-nucleotide fragment resulted in the complete loss of promoter activity (Fig. 2B). Smaller deletions from the 3′ end of the 2,051-nucleotide sequence resulted in either partial or no loss in promoter activity in each cell line. These results define the 5′ boundary of the cycT1 promoter as lying between 299 and 545 nucleotides 5′ to the translation initiation site.

FIG. 2.

Functional analysis of the cycT1 promoter in immortalized cell lines. Jurkat (T cells), 293T (epithelial), or U937 (monocytic) cell lines were transfected with pGL3-derived luciferase reporter plasmids. (A) The 5′ deletion series contains human genomic sequences from the CycT1 translation intiation site extending 5′ to the indicated nucleotide; 545R represents the complete 545-nucleotide promoter iserted into pGL3 in the reverse orientation. (B) The 3′ deletion series contains sequences from position −2051 relative to the CycT1 translation initiation site extending 3′ to the indicated nucleotide. In each case, cells were cotransfected with pBC12/CMV/lacZ. The luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were determined in cell lysates 48 h after transfection. Promoter activity is expressed as a percentage of the luciferase activity present in cells transfected with a reporter plasmid containing the 545-nucleotide promoter (determined, by this analysis, to contain the entire transcription promoting activity) and were normalized for minor variations in transfection efficiency, as determined from the β-galactosidase activity.

Progressive 5′-to-3′ deletion analysis of this 545 nucleotide sequence, shown in Fig. 2A, initially revealed modest effects on promoter activity. Indeed, fragments containing 350, 299, 265, or 205 nucleotides 5′ to the cycT1 translation initiation site retained 70 to 100% of the activity of the intact 545-nucleotide promoter. Further, 5′-to-3′ deletions had more significant and cell-type dependent effects on promoter activity. Specifically, removal of sequences between position −205 and either position −165 or position −120 resulted in fragments that retained 60 to 100% activity in Jurkat cells but only 20 to 30% activity in either 293T or U937 cells. In addition, very small 3′ fragments of the cycT1 promoter (98 and 76 nucleotides) were inactive in 293T and U937 cells but retained approximately 10% of the activity of the full 545-nucleotide promoter in Jurkat cells.

Conversely, 3′-to-5′ deletion analysis, shown in Fig. 2B, did not reveal any major cell type-dependent differences in the activity of truncated promoters. In all three cell lines, the deletion of 116 nucleotides from the 3′ end of the promoter sequence did not result in any significant loss in activity. However, further 3′ deletions of 205 or 299 nucleotides resulted in similar, partial losses in promoter activity in each cell line. Interestingly, when viewed in combination, these 5′ and 3′ deletion analyses reveals functional redundancy in the cycT1 promoter; sequences which are in themselves fully sufficient to act as promoters can be deleted without loss of promoter activity. For example, the 116 nucleotides situated at the 3′ end of the promoter that are not required for full promoter activity in any cell line (Fig. 2B) nevertheless constitute a fully active promoter in Jurkat cells and a partially active promoter in 293T and U937 cells (Fig. 2A).

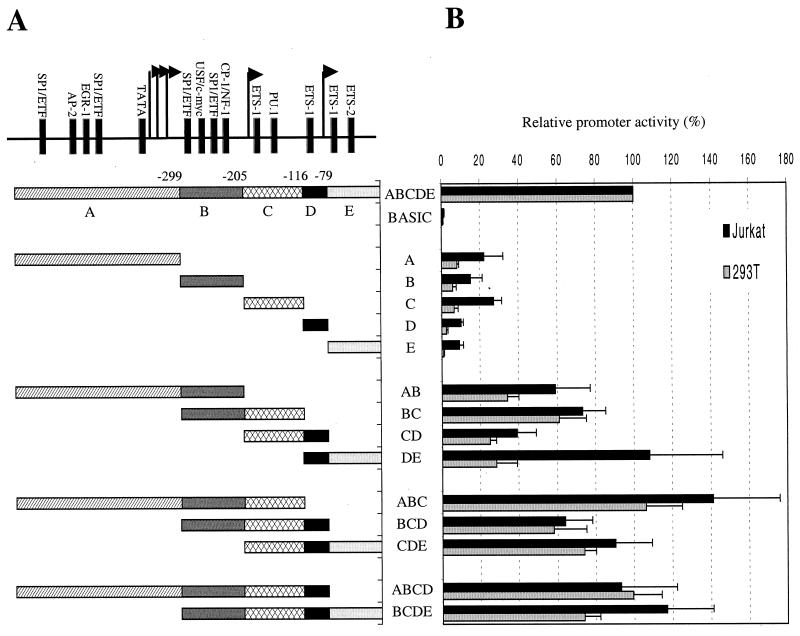

These results are largely consistent with a recent study of Liu and Rice (34), who concluded that the cycT1 promoter includes two regions with critical regulatory elements, situated between positions −503 and −190 and positions −146 and −92. However, to functionally dissect the cycT1 promoter in more detail, we constructed a series of reporter plasmids that combined both 5′ and 3′ deletions and analyzed their ability to function as promoters in the three cell lines. Since the results obtained with 293T and U937 cells were very similar, only those obtained with 293T cells are presented, in addition to those obtained using Jurkat cells. These results are summarized in Fig. 3 and reveal a remarkable level of functional redundancy in the cycT1 promoter. Ultimately, we defined no less than five nonoverlapping cycT1 promoter fragments that retained 10 to 20% of the activity of the intact promoter in at least one of the cell lines. For simplicity we have termed these promoter “modules” A (−545 to −300), B (−299 to −206), C (−205 to −117), D (−116 to −80), and E (−79 to +1).

FIG. 3.

Combinatorial analysis of minimally active cycT1 promoter fragments in immortalized cell lines. (A) Minimal cycT1 promoter fragments, found to retain at least 10% of the intact promoter activity are termed modules A (−545 to −300), B (−299 to −206), C (−205 to −117), D (−116 to −80), and E (−79 to +1). These were analyzed individually or as all possible contiguous combinations of two, three, or four modules. (B) Luciferase activities resulting from transfection of Jurkat and 293T cells with reporter plasmids are expressed as a percentage of that obtained after transfection of a construct containing the intact 545-nucleotide cycT1 promoter.

As is shown in Fig. 3, combinatorial analysis of these contiguous minimal promoter modules revealed a complex relationship between sequence elements that can act either synergistically, additively, or redundantly to promote cycT1 transcription. In fact, each combination of two contiguous minimal promoter elements (A-B, B-C, C-D, and D-E) gave promoter activities that were greater the sum of the individual contributing elements. For example, promoter module E was inactive in 293T cells and possessed ca. 10% of the activity of the intact cycT1 promoter in Jurkat cells. Similarly, module D possessed only 2.4% activity in 293T cells and 10% of the intact promoter activity in Jurkat cells (Fig. 3). However, when present in combination, in module D-E, the 108 and 23% of the intact promoter activity was observed in Jurkat and 293T cells, respectively. Clearly, therefore, elements contained within these minimal modules can act synergistically to drive transcription by the cycT1 promoter. The one exception to this finding was the C-D combination, which gave 39% of full promoter activity in Jurkat cells, a value approximately equal to the sum of that of the individual C (27%) and D (10%) modules. The addition of a third minimal promoter module to each of the two module combinations had variable effects on promoter activity. For instance, the addition of module A to the B-C combination (resulting in A-B-C) significantly enhanced the promoter in each cell line. Similarly, A-B-C was significantly more active than A-B. Taken together, these results suggest that elements in modules A, B, and C act cooperatively to promote cycT1 transcription. In contrast, the presence of the D module in the context of a promoter containing both B and C elements had no enhancing effect on activity (compare B-C versus B-C-D in Fig. 3). In fact, the contribution of module D to promoter activity was highly context dependent: it potently enhanced promoter activity in the context of a D-E combination and, more modestly, in the context of a C-D combination. This observation suggests that sequences in module D can act cooperatively with those present in E and, to a lesser extent, in C but not in A or B to promote cycT1 transcription. This conclusion is supported by the observation that the addition of module E to the C-D combination (resulting in C-D-E) also significantly enhanced promoter activity (Fig. 3). The addition of either module A or module E to the central B-C-D module combination, to give A-B-C-D and B-C-D-E, respectively, also resulted in significant increases in activity so that each four module-containing promoters possessed 75 to 100% of the activity of the intact cycT1 promoter (Fig. 3).

Comparison of the activities of these two- and three-module containing, truncated promoters clearly demonstrates a significant degree of functional redundancy in the cycT1 promoter. Both the A-B-C and the C-D-E promoter constructs possessed activities that are close to or equal to that of the intact promoter in both cell lines. In fact, it proved possible to derive two nonoverlapping portions of the cycT1 promoter that retained activities that were at least as high as that of intact promoter in Jurkat cells (A-B-C and D-E; Fig. 3).

Definition of cycT1 promoter elements that respond to cellular activation stimuli.

Having defined minimal promoter elements that contribute to the transcription of the cycT1 gene, we next sought to identify which, if any, of these sequences is responsible for the upregulation of cycT1 expression in response to cellular activation stimuli. Unfortunately, we were unable to identify any cellular activation stimulus that resulted in a robust increase in the activity of the cycT1 promoter in either Jurkat or U937 cells. Liu and Rice recently reported that a combination of PMA and ionomycin can modestly increase the activity of the cycT1 promoter in Jurkat cells (34). However, this effect is <2-fold and unlikely to be sufficient for unambiguous mapping of the elements responsible for activation-induced upregulation.

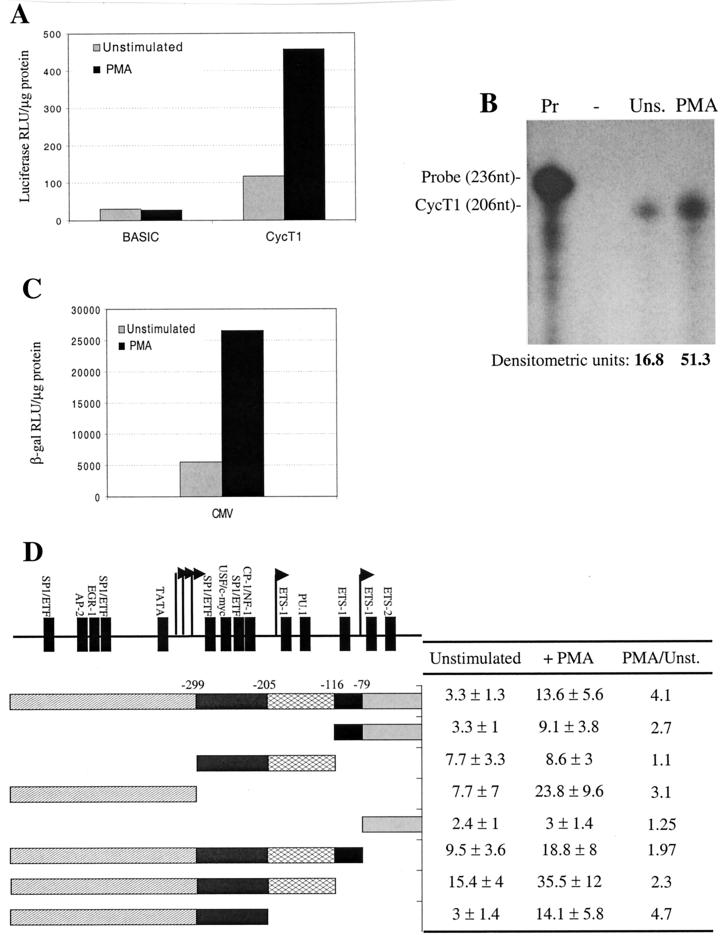

Consequently, we used experimental conditions (3) that permitted the measurement of cycT1 promoter activity in primary lymphocyte cultures. Results from these experiments are shown in Fig. 4. Transfection of a luciferase reporter construct containing the intact 545-nucleotide cycT1 promoter resulted in levels of luciferase expression that were readily detectable and three- to four-fold higher than that observed after transfection of the control promoterless reporter construct (Fig. 4A). Subsequently, transfected primary lymphocyte cultures were subjected to a variety of activation stimuli. Of these, only PMA treatment led to a robust and reproducible increase (ca. fourfold) in the level of cycT1 promoter driven luciferase expression (Fig. 4A and data not shown). To confirm that this PMA-mediated effect was not simply an artifact of using transfected plasmid DNA, we also measured the level of cycT1 mRNA expression from the endogenous cycT1 gene by using untransfected cells. As is shown in Fig. 4B, PMA treatment resulted in a similar increase (three- to fourfold) in the level of endogenous cycT1 transcription, as measured by RNase protection assay. The magnitude of these effects was similar to that observed when the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter, which is known to be PMA responsive, was used in place of the cycT1 promoter (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

Analysis of cycT1 promoter activity in primary lymphocytes. (A) Primary lymphocytes obtained from a normal donor were electroporated with pGL3-based plasmids either that lacked a promoter or contained the 545-nucleotide cycT1 promoter. (B) RNase protection analysis of endogenous cycT1 transcription with total RNA extracted from nontransfected, unsimulated (Uns) or PMA-treated primary lymphocytes. Lanes: Pr, undigested cycT1 probe; −, digested probe after hybridization with yeast tRNA. (C) Cells from the same donor as in panel A were transfected with pBC12/CMV/lacZ. For both panels A and C, cells were either left unstimulated or were treated with PMA after transfection. Luciferase or β-galactosidase activities in cell lysates were determined 24 h after electroporation and are representative of at least three independent experiments. (D) Primary lymphocytes were electroporated with reporter plasmids containing selected cycT1 promoter fragments, and cells either were left unstimulated or were treated with PMA. Results are presented as the fold increase in luciferase activity (± the standard deviation) over that obtained with a promoterless reporter plasmid and lymphocytes from three different donors.

Thereafter, we used selected constructs to determine which of the minimal cycT1 promoter modules, described in Fig. 3, mediate both basal and PMA-responsive reporter gene expression in primary lymphocyte cultures. As is shown in Fig. 4D, a truncated promoter consisting of modules D and E appeared to be as active as the intact cycT1 promoter. This is a similar result to that obtained with the Jurkat T-cell line (Fig. 3). Furthermore, this D-E promoter module combination was clearly PMA responsive, albeit slight less so than the intact cycT1 promoter. Module D was required for PMA-responsive transcription in this context because no PMA-induced enhancement of reporter gene expression was observed with a construct that contained module E alone. Surprisingly, a promoter containing only modules B and C had a higher basal activity than the intact cycT1 promoter, but these modules did not exhibit any increase in reporter gene expression upon PMA treatment of transfected cells. Promoter module A, however, exhibited both a higher basal level of expression and was responsive to PMA treatment. These data suggested that at least one element exists in the cycT1 promoter that can inhibit transcription in primary lymphocytes. To address this further, cells were transfected with reporter constructs that contained either A-B, A-B-C, or A-B-C-D module combinations (Fig. 4D). As expected, each of these truncated promoters retained at least some degree of PMA responsiveness. However, a promoter containing modules A and B exhibited lower activity in both the presence and the absence of PMA than did one containing module A alone, suggesting that sequences in module B can exert an inhibitory effect in this context. Likewise, a promoter containing module combination A-B-C-D possessed a lower activity than did one containing A-B-C. Nevertheless, A-B-C-D was slightly more active than the intact promoter, A-B-C-D-E. It appears, therefore, that sequences in modules B, D, and E can exert an inhibitory effect on both basal and PMA-activated transcription driven by cycT1 promoter in primary lymphocytes, depending on the context in which they are present.

Overall, the data in Fig. 4D indicates that the cycT1 promoter contains at least three sequence elements that are capable of functioning independently and contribute to overall promoter activity in transfected primary lymphocytes: (i) a distal element within module A that contributes to both basal and PMA-responsive transcription, (ii) a central element contained within modules B and C that contributes to the basal transcription but not PMA responsiveness, and (iii) a proximal element contained within modules D and E that contributes to both basal and PMA-activated transcription. In addition, it appears that sequences within the cycT1 promoter can exert a context-dependent inhibitory influence on promoter activity.

Changes in the utilization of transcription initiation sites within the cycT1 promoter upon cellular activation.

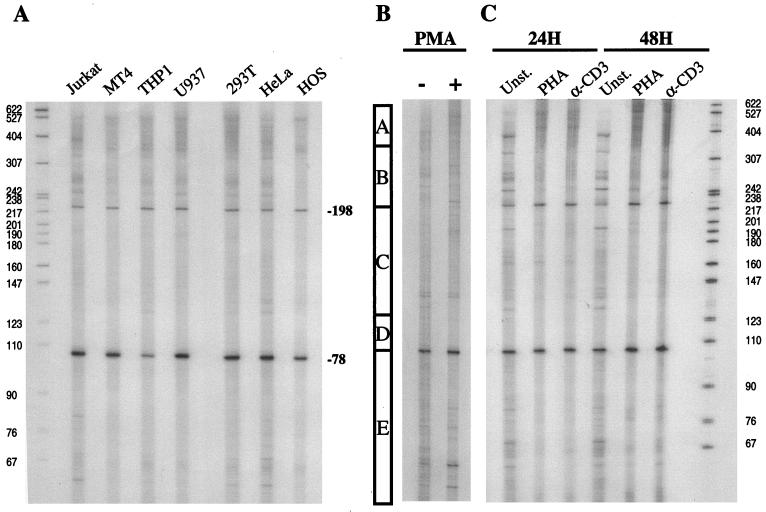

The finding that no single module within the cycT1 promoter was required for efficient transcription suggested that more than one sequence was at least capable of serving as a transcription initiation site. To address this specifically, we performed primer extension analyses of endogenous cycT1 mRNA by using a primer complementary to the extreme 5′ end of the cycT1 coding sequence. RNA isolated from several cell lines was analyzed, and these data are presented in Fig. 5A. In all cell lines examined, two discrete major transcription start sites were detected at around positions −80 and −200. In addition, several minor bands were observed as well as a heterogeneous population of higher-molecular-weight extension products that could not be resolved to determine discrete initiation sites. It was initially unclear whether these minor bands represent specific transcription start sites. Nevertheless, it is clear that the start sites at positions −80 and −200 are, in part, redundant since high level activity could be observed in truncated promoters that lacked one or other of these sites. Indeed, the promoter module combination A-B, which lacks both of these discrete sites, retained 35 and 60% of full promoter activity in 293T and Jurkat cells (Fig. 3), respectively, and full activity in primary lymphocytes (Fig. 4), indicating that neither is essential.

FIG. 5.

Transcription start site utilization at the cycT1 promoter in immortalized cell lines and primary lymphocytes. (A) Total RNA was obtained from a panel of immortalized cell lines and subjected to primer extension analysis with an oligonucleotide proximal to the cycT1 translation start site (T1GP1; see Materials and Methods). Similar analyses were done with RNA extracted from primary lymphocytes that were either unstimulated or subjected to treatment with PMA for 24 h (B) or treatment with either PHA or αCD3 antibody for 24 and 48 h (C). The bar in panel B indicates the boundaries of the promoter modules A, B, C, and D as defined in Fig. 3.

A recent analysis of the cycT1 promoter by Liu and Rice (34) indicated the presence of transcription initiation sites at approximately positions −80 and −135, as determined by RNase protection assays, and at −323 and −324 as determined by primer extension. The data presented here are partially concordant with these findings, However, the −323 and −324 start sites reported by Liu and Rice would fall within the heterogeneous high-molecular-weight extension products observed in our experiments. In addition, we did not detect a major transcription start site at −135 (although minor bands in this region were observed). Instead, we clearly observed transcripts initiating at −200. Despite these minor discrepancies, which could, in part, be due to the different RNA source (HL-60 cells) used by Liu and Rice (34), it is abundantly clear that transcription can initiate at multiple sites within the cycT1 promoter.

To investigate whether endogenous cycT1 transcription in general, and start site utilization in particular, could be influenced by cellular activation state, we isolated RNA from primary lymphocytes that were either unstimulated or had been treated with various activating agents. Primer extension analyses of these RNAs are presented in Fig. 5B. Unstimulated lymphocytes contained a particularly diverse population of cycT1 transcripts, initiated at multiple sites, with the most prominent start site positioned at −80. A minor degree of donor-to-donor variation in the pattern of primer extension products obtained with unstimulated primary lymphocytes was evident (compare Fig. 5B and C). Upon stimulation with PMA, however, a dramatic change in the utilization of transcription start sites was observed (Fig. 5B). Specifically, PMA reproducibly increased the utilization of discrete transcription start sites at positions −40, −80, and −200. In addition, an increased level of the heterogeneous high-molecular-weight primer extension products was clearly observed upon analysis of RNA from PMA-treated cells. Thus, PMA-induced cycT1 transcripts appear to initiate predominantly within promoter modules A and D-E. This result correlates with the ability of these promoter modules to mediate enhanced reporter gene expression in response to the PMA treatment of transfected primary lymphocytes (Fig. 4).

Slightly different results in the pattern of cycT1 specific transcript initiation were obtained with primary lymphocytes that had been treated with either phytohemagglutinin (PHA) or with an αCD3 antibody (Fig. 5C). In this case, stimulation appeared to markedly reduce the complexity of the pattern of primer extension products. Specifically, many of the minor primer extension products that were observed with RNA isolated from unstimulated cells were not detected when PHA- or anti-CD3-stimulated cells were analyzed. Instead, transcription start sites at −80 and −200 were utilized somewhat more efficiently, and there was a dramatic increase in the level of heterogeneous high-molecular-weight extension products. These effects were more evident at 48 h after treatment than after 24 h. The transcription initiation site at around position −40, which was induced by PMA, was not induced by either PHA or αCD3. In contrast to unstimulated primary lymphocytes, the pattern of transcription initiation sites observed in PHA- or anti-CD3-treated cells closely resembled that observed in the panel of immortalized cell lines shown in Fig. 5A. In summary, these analyses demonstrate that cellular activation dramatically influences transcription start site selection but results in a modest overall increase in cycT1 transcription (Fig. 4B).

CycT1 is expressed at sufficient levels to support efficient Tat function in unstimulated primary lymphocytes.

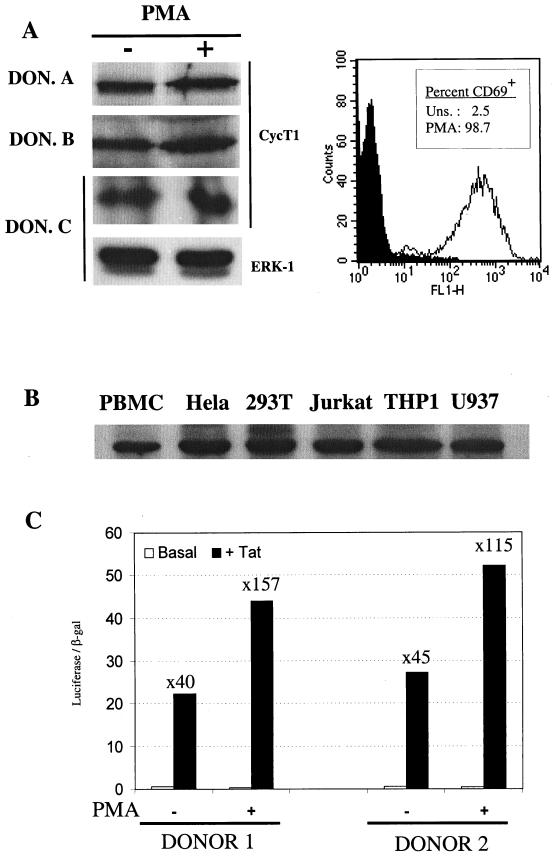

Previously, it has been reported that CycT1 protein levels are low in unstimulated lymphocytes (25, 26), and this led to the hypothesis that activation-induced replication of HIV-1 in primary lymphocyte cultures is a consequence of increased levels of CycT1 expression (44, 48). Indeed, the reported excess of short compared to long HIV-1 transcripts in the unstimulated lymphocytes of HIV-1-infected individuals (1) would be the predicted consequence of defective Tat function consequent to limiting levels of CycT1. However, we observed rather modest upregulation of cycT1 promoter-driven reporter gene expression and concordant increases in the total level of cycT1 mRNA (Fig. 4) in response to a potent activation stimulus (PMA). These observations prompted us to reexamine the level of CycT1 protein in stimulated versus unstimulated primary cells and to ask whether this level is sufficient to support Tat function. Therefore, we obtained primary lymphocytes from multiple HIV-negative donors and examined the level of CycT1 protein expression by Western blotting. CycT1 expression in the untreated and PMA-stimulated lymphocytes of three representative donors is shown in Fig. 6A. In fact, we observed only small increases in CycT1 protein levels in response to PMA in all donors examined. In some cases, we also performed Western analysis with a monoclonal antibody specific for ERK-1, whose expression remains constant upon activation, to confirm equivalent gel loading. Moreover, analysis of activation marker (CD69) expression in primary lymphocytes established the resting and activated states of the unstimulated and PMA-treated cells, respectively (Fig. 6A). This modest increase in CycT1 protein levels upon PMA treatment can readily be accounted for (and, in fact, appears to be less than) the increase in transcription from the cycT1 promoter in response to PMA activation (Fig. 4 and 5). Similar results were obtained when PHA was used as the stimulus and are in contrast with the previously reported marked increase in CycT1 protein levels in primary lymphocytes after PMA or PHA activation (25, 26).

FIG. 6.

CycT1 is expressed in unstimulated primary lymphocytes at levels sufficient to support Tat function. (A) Western blot analysis of CycT1 expression in primary lymphocytes obtained from three representative donors that either were unstimulated or were treated with PMA for 24 h. As a loading control, some blots were also probed with an anti-ERK-1 antibody. The panel to the right shows FACS analysis of unstimulated and PMA-treated lymphocytes with an anti-CD69 monoclonal antibody. (B) Comparative Western blot analysis of CycT1 expression levels in freshly isolated, unstimulated primary lymphocytes and a panel of immortalized cell lines known to support HIV-1 Tat function or virus replication. (C) Analysis of Tat function in unstimulated or PMA-treated primary lymphocytes. Data obtained with lymphocytes from two representative donors, electroporated with pHIV/luc, pBC12/CMV/lacZ, and either pcTat or pBC12/CMV is shown. The luciferase and β-galactosidase activities in cell lysates were determined 24 h after electroporation. For each experiment, the fold increase in luciferase expression in response to Tat is shown.

We further examined, in a comparative manner, the level of CycT1 protein present in unstimulated primary lymphocytes and a panel of immortalized cell lines in which HIV-1 has been shown to replicate efficiently or have been documented to support robust Tat activity. A representative experiment is shown in Fig. 6B. In fact, CycT1 expression in unstimulated primary lymphocytes was only slightly lower than that observed in each of the immortalized cell lines. This observation argues against the notion that a lack of CycT1 expression limits Tat function and HIV-1 gene expression in unstimulated primary lymphocytes.

However, to address this question directly, we performed transfection experiments in which an HIV-1 LTR promoter-driven luciferase reporter plasmid was electroporated into primary lymphocytes in the presence or absence of a Tat expression plasmid. These results are shown in Fig. 6C. After transfection, cells were cultured for 24 h in the absence of stimulation or were treated with PMA. While PMA clearly induces the HIV-1 LTR (and the cotransfected CMV-LacZ control plasmid) approximately fourfold, it is clear that PMA treatment had only minor effects on Tat function. Indeed, Tat was able to transactivate the HIV-1 LTR 40- to 45-fold in primary cells that were otherwise unstimulated, a result that is similar to that observed in many immortalized cell lines. PMA treatment did result in a small but measurable increase (two- to threefold) in Tat transactivation. However, this is as likely due to a PMA-induced increase in Tat expression (mediated by the CMV promoter in pcTat) or to synergy between PMA-induced transcription initiation and Tat-induced transcription elongation, as to the minor increase in CycT1 expression observed upon PMA treatment of primary lymphocytes. Clearly, CycT1 and P-TEFb levels do not appear to profoundly limit Tat function in unstimulated primary lymphocytes.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we have determined that the cycT1 gene harbors a complex promoter containing elements that can function both cooperatively and redundantly to mediate transcription. Initiation of cycT1 transcription can occur at multiple sites within the promoter (Fig. 5) (34), a feature that is not unusual among the constitutively active Tata-less promoters that are typical of “housekeeping” genes. Other features of the cycT1 promoter that are often shared among housekeeping genes include the fact that it is situated within a CpG-rich “island” and contains significant functional redundancy (4, 46). However, it is remarkable and without precedent (as far as we are aware) that no less than five nonoverlapping fragments of the complete promoter exhibit an ability to promote transcription to a significant degree (Fig. 3). It is also noteworthy that no single sequence element within the cycT1 promoter, including a consensus TATA element located at position −378, appears to be essential for full activity. This finding makes an assessment of a role for individual transcription factors in driving cycT1 transcription problematic; while there are many predicted binding sites for transcription factors in the cycT1 promoter (Fig. 1) (34), none appears to be essential for cycT1 transcription. Moreover, it appears that, with the exception of four binding sites for Ets family transcription factors, none of the putative transcription factor binding sites are conserved in the human and murine cycT1 promoters. It appears likely, therefore, that evolution has selected cycT1 promoter sequences that are active in a wide variety of cell types, in different states of activation, in which different transcription factors might be present, without a specific requirement for a given promoter sequence or transcription factor.

Nevertheless, the conservation of the putative Ets binding sites in human and murine cycT1 promoters is striking (Fig. 1). The Ets family of transcriptional regulators is large and diverse and binds to the core sequence GGAA/T with proximal sequences (up to a total of 15 nucleotides) influencing which particular Ets family member is recruited (reviewed in reference 45). The Ets core binding site occurs five times in between positions −180 and −40 in the 3′ portion of the cycT1 promoter (Fig. 1). Each of these elements is homologous to sequences previously shown to act as binding sites for either the Ets-1, PEA3, Ets-2, or PU.1 members of the Ets family. Interestingly, Ets-1 and -2 are known to be reciprocally regulated during T-cell activation; in resting cells Ets-2 is abundant and Ets-1 is poorly expressed, whereas the converse is the case in activated T cells (6). It is likely, therefore, that cycT1 promoter modulation and transcription start site selection within the 3′ portion of the promoter could be mediated, in part, by Ets family factors. Indeed, initiation site selection in primary lymphocyte cells appeared to be highly dependent on the cellular activation state (Fig. 5). These findings are consistent with the notion that the position to which the RNAPII complex is recruited and initiates transcription within a Tata-less promoter is, in part, dependent on the array of transcription factors bound to the regulatory sequences within promoter elements. Clearly, the analysis of deleted cycT1 promoter constructs reveals that CycT1 expression is not entirely dependent on Ets family members nor on any other single transcription factor.

Despite the quite dramatic changes in cycT1 transcription start site selection that occur upon cellular activation (Fig. 5), unstimulated primary lymphocytes retain significant cycT1 promoter activity and contain readily detectable levels of CycT1 protein (Fig. 4, 5, and 6). In these experiments, very little change in the steady-state levels of CycT1 protein in either cell lines or primary lymphocytes were detected in response to exogenous activation stimuli. This finding contrasts with those of Garriga et al. and Hermann et al. (25, 26) and may relate to the different methods used for cell lysis. In some cell lines, notably U937, we found it difficult to detect CycT1 protein by Western blotting when cells were disrupted by nondenaturing lysis buffers (data not shown). In contrast, cell lysis under denaturing conditions prior to Western blotting led to a rather uniform yield of CycT1 protein (Fig. 6). In fact, it has been recently shown that a proportion of CycT1 is associated with the insoluble nuclear matrix and is not efficiently extracted by using nondenaturing detergents (27). The discrepancies between this and previous studies may, therefore, be a consequence of cell type- or activation state-dependent differences in the localization and/or biochemical properties of CycT1 protein.

It is somewhat surprising that both cycT1 promoter-driven reporter gene expression (Fig. 4) and endogenous cycT1 mRNA levels (Fig. 5) are measurably increased by activation of primary lymphocytes, and yet changes in the CycT1 protein levels are barely detectable (Fig. 6). CycT1 appears to be relatively stable in 293T cells, with a half-life of ca. 48 h (42), despite the presence of a putative PEST sequence. Whether this is true in all cellular contexts is unclear. It might be that cellular activation increases both synthesis and degradation of CycT1. Nevertheless, the steady-state levels of CycT1 do not appear to dramatically change in response to cellular activation.

An important functional consequence of these findings is that the HIV-1 Tat protein, which activates transcription by recruitment of the CycT1 containing form of P-TEFb to the viral LTR promoter, possesses significant intrinsic activity in unstimulated primary lymphocytes. In fact, PMA activation leads to an only two- to three-fold increase in Tat activity (Fig. 6). Other variables, such as NF-κB activity, which is dramatically influenced by the cellular activation state, and the site of proviral integration have been clearly demonstrated modulate the level of gene expression from the HIV-1 LTR (3, 13, 30, 39, 40, 54). Given these observations and the findings reported here, it appears extremely unlikely that the transcriptional activity or latency of the HIV-1 provirus in vivo is explained by the presence of limiting quantities of the CycT1 containing form of P-TEFb.

Acknowledgments

We thank Amanda Brown, Cecilia Cheng-Mayer, and Mark Muesing for gifts of reagents.

This work was supported by the Donald A. Pels Charitable Trust.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, M., L. Sharmeen, J. Kimpton, J. M. Romeo, J. V. Garcia, B. M. Peterlin, M. Groudine, and M. Emerman. 1994. Cellular latency in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals with high CD4 levels can be detected by the presence of promoter-proximal transcripts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:3862–3866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albrecht, T. R., L. H. Lund, and M. A. Garcia-Blanco. 2000. Canine cyclin T1 rescues equine infectious anemia virus tat trans-activation in human cells. Virology 268:7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alcami, J., T. Lain de Lera, L. Folgueira, M. A. Pedraza, J. M. Jacque, F. Bachelerie, A. R. Noriega, R. T. Hay, D. Harrich, R. B. Gaynor, et al. 1995. Absolute dependence on kappa B responsive elements for initiation and Tat-mediated amplification of HIV transcription in blood CD4 T lymphocytes. EMBO J. 14:1552–1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antequera, F., and A. Bird. 1999. CpG islands as genomic footprints of promoters that are associated with replication origins. Curr. Biol. 9:R661–R667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barboric, M., R. Taube, N. Nekrep, K. Fujinaga, and B. M. Peterlin. 2000. Binding of Tat to TAR and recruitment of positive transcription elongation factor b occur independently in bovine immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 74:6039–6044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhat, N. K., C. B. Thompson, T. Lindsten, C. H. June, S. Fujiwara, S. Koizumi, R. J. Fisher, and T. S. Papas. 1990. Reciprocal expression of human ETS1 and ETS2 genes during T-cell activation: regulatory role for the protooncogene ETS1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:3723–3727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bieniasz, P. D., T. A. Grdina, H. P. Bogerd, and B. R. Cullen. 1999. Analysis of the effect of natural sequence variation in Tat and in cyclin T on the formation and RNA binding properties of Tat-cyclin T complexes. J. Virol. 73:5777–5786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bieniasz, P. D., T. A. Grdina, H. P. Bogerd, and B. R. Cullen. 1999. Highly divergent lentiviral Tat proteins activate viral gene expression by a common mechanism. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:4592–4599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bieniasz, P. D., T. A. Grdina, H. P. Bogerd, and B. R. Cullen. 1998. Recruitment of a protein complex containing Tat and cyclin T1 to TAR governs the species specificity of HIV-1 Tat. EMBO J. 17:7056–7065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bieniasz, P. D., T. A. Grdina, H. P. Bogerd, and B. R. Cullen. 1999. Recruitment of cyclin T1/P-TEFb to an HIV type 1 long terminal repeat promoter proximal RNA target is both necessary and sufficient for full activation of transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:7791–7796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bogerd, H. P., H. L. Wiegand, P. D. Bieniasz, and B. R. Cullen. 2000. Functional differences between human and bovine immunodeficiency virus Tat transcription factors. J. Virol. 74:4666–4671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bukrinsky, M. I., T. L. Stanwick, M. P. Dempsey, and M. Stevenson. 1991. Quiescent T lymphocytes as an inducible virus reservoir in HIV-1 infection. Science 254:423–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, B. K., M. B. Feinberg, and D. Baltimore. 1997. The κB sites in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat enhance virus replication yet are not absolutely required for viral growth. J. Virol. 71:5495–5504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chun, T. W., L. Stuyver, S. B. Mizell, L. A. Ehler, J. A. Mican, M. Baseler, A. L. Lloyd, M. A. Nowak, and A. S. Fauci. 1997. Presence of an inducible HIV-1 latent reservoir during highly active antiretroviral therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:13193–13197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dahmus, M. E. 1996. Reversible phosphorylation of the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. J. Biol. Chem. 271:19009–19012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feinberg, M. B., D. Baltimore, and A. D. Frankel. 1991. The role of Tat in the human immunodeficiency virus life cycle indicates a primary effect on transcriptional elongation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:4045–4049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng, S., and E. C. Holland. 1988. HIV-1 tat trans-activation requires the loop sequence within tar. Nature 334:165–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finzi, D., M. Hermankova, T. Pierson, L. M. Carruth, C. Buck, R. E. Chaisson, T. C. Quinn, K. Chadwick, J. Margolick, R. Brookmeyer, J. Gallant, M. Markowitz, D. D. Ho, D. D. Richman, and R. F. Siliciano. 1997. Identification of a reservoir for HIV-1 in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Science 278:1295–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fong, Y. W., and Q. Zhou. 2000. Relief of two built-In autoinhibitory mechanisms in P-TEFb is required for assembly of a multicomponent transcription elongation complex at the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:5897–5907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu, T. J., J. Peng, G. Lee, D. H. Price, and O. Flores. 1999. Cyclin K functions as a CDK9 regulatory subunit and participates in RNA polymerase II transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 274:34527–34530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujinaga, K., T. P. Cujec, J. Peng, J. Garriga, D. H. Price, X. Grana, and B. M. Peterlin. 1998. The ability of positive transcription elongation factor B to transactivate human immunodeficiency virus transcription depends on a functional kinase domain, cyclin T1, and Tat. J. Virol. 72:7154–7159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujinaga, K., R. Taube, J. Wimmer, T. P. Cujec, and B. M. Peterlin. 1999. Interactions between human cyclin T, Tat, and the transactivation response element (TAR) are disrupted by a cysteine to tyrosine substitution found in mouse cyclin T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:1285–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garber, M. E., T. P. Mayall, E. M. Suess, J. Meisenhelder, N. E. Thompson, and K. A. Jones. 2000. CDK9 autophosphorylation regulates high-affinity binding of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 tat-P-TEFb complex to TAR RNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:6958–6969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garber, M. E., P. Wei, V. N. KewalRamani, T. P. Mayall, C. H. Herrmann, A. P. Rice, D. R. Littman, and K. A. Jones. 1998. The interaction between HIV-1 Tat and human cyclin T1 requires zinc and a critical cysteine residue that is not conserved in the murine CycT1 protein. Genes Dev. 12:3512–3527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garriga, J., J. Peng, M. Parreno, D. H. Price, E. E. Henderson, and X. Grana. 1998. Upregulation of cyclin T1/CDK9 complexes during T cell activation. Oncogene 17:3093–3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herrmann, C. H., R. G. Carroll, P. Wei, K. A. Jones, and A. P. Rice. 1998. Tat-associated kinase, TAK, activity is regulated by distinct mechanisms in peripheral blood lymphocytes and promonocytic cell lines. J. Virol. 72:9881–9888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herrmann, C. H., and M. A. Mancini. 2001. The Cdk9 and cyclin T subunits of TAK/P-TEFb localize to splicing factor-rich nuclear speckle regions. J. Cell Sci. 114:1491–1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herrmann, C. H., and A. P. Rice. 1995. Lentivirus Tat proteins specifically associate with a cellular protein kinase, TAK, that hyperphosphorylates the carboxyl-terminal domain of the large subunit of RNA polymerase II: candidate for a Tat cofactor. J. Virol. 69:1612–1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horvat, R. T., and C. Wood. 1989. HIV promoter activity in primary antigen-specific human T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 143:2745–2751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jordan, A., P. Defechereux, and E. Verdin. 2001. The site of HIV-1 integration in the human genome determines basal transcriptional activity and response to Tat transactivation. EMBO J. 20:1726–1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kao, S. Y., A. F. Calman, P. A. Luciw, and B. M. Peterlin. 1987. Anti-termination of transcription within the long terminal repeat of HIV-1 by tat gene product. Nature 330:489–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kinoshita, S., L. Su, M. Amano, L. A. Timmerman, H. Kaneshima, and G. P. Nolan. 1997. The T cell activation factor NF-ATc positively regulates HIV-1 replication and gene expression in T cells. Immunity 6:235–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laspia, M. F., A. P. Rice, and M. B. Mathews. 1989. HIV-1 Tat protein increases transcriptional initiation and stabilizes elongation. Cell 59:283–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu, H., and A. P. Rice. 2000. Isolation and characterization of the human cyclin T1 promoter. Gene 252:39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu, Y. C., N. Touzjian, M. Stenzel, T. Dorfman, J. G. Sodroski, and W. A. Haseltine. 1991. The NF-kappa B independent cis-acting sequences in HIV-1 LTR responsive to T-cell activation. J. Acquir. Immune. Defic. Syndr. 4:173–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Majello, B., G. Napolitano, A. Giordano, and L. Lania. 1999. Transcriptional regulation by targeted recruitment of cyclin-dependent CDK9 kinase in vivo. Oncogene 18:4598–4605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marciniak, R. A., and P. A. Sharp. 1991. HIV-1 Tat protein promotes formation of more-processive elongation complexes. EMBO J. 10:4189–4196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marshall, N. F., J. Peng, Z. Xie, and D. H. Price. 1996. Control of RNA polymerase II elongation potential by a novel carboxyl-terminal domain kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 271:27176–27183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nabel, G., and D. Baltimore. 1987. An inducible transcription factor activates expression of human immunodeficiency virus in T cells. Nature 326:711–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nahreini, P., and M. B. Mathews. 1997. Transduction of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 promoter into human chromosomal DNA by adeno-associated virus: effects on promoter activity. Virology 234:42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Napolitano, G., P. Licciardo, P. Gallo, B. Majello, A. Giordano, and L. Lania. 1999. The CDK9-associated cyclins T1 and T2 exert opposite effects on HIV-1 Tat activity. AIDS 13:1453–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Keeffe, B., Y. Fong, D. Chen, S. Zhou, and Q. Zhou. 2000. Requirement for a kinase-specific chaperone pathway in the production of a Cdk9/cyclin T1 heterodimer responsible for P-TEFb-mediated tat stimulation of HIV-1 transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 275:279–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peng, J., Y. Zhu, J. T. Milton, and D. H. Price. 1998. Identification of multiple cyclin subunits of human P-TEFb. Genes Dev. 12:755–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Price, D. H. 2000. P-TEFb, a cyclin-dependent kinase controlling elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:2629–2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sementchenko, V. I., and D. K. Watson. 2000. Ets target genes: past, present and future. Oncogene 19:6533–6548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Somma, M. P., C. Pisano, and P. Lavia. 1991. The housekeeping promoter from the mouse CpG island HTF9 contains multiple protein-binding elements that are functionally redundant. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:2817–2824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stevenson, M., T. L. Stanwick, M. P. Dempsey, and C. A. Lamonica. 1990. HIV-1 replication is controlled at the level of T cell activation and proviral integration. EMBO J. 9:1551–1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taube, R., K. Fujinaga, J. Wimmer, M. Barboric, and B. M. Peterlin. 1999. Tat transactivation: a model for the regulation of eukaryotic transcriptional elongation. Virology 264:245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tiley, L. S., S. J. Madore, M. H. Malim, and B. R. Cullen. 1992. The VP16 transcription activation domain is functional when targeted to a promoter-proximal RNA sequence. Genes Dev. 6:2077–2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wada, T., G. Orphanides, J. Hasegawa, D. K. Kim, D. Shima, Y. Yamaguchi, A. Fukuda, K. Hisatake, S. Oh, D. Reinberg, and H. Handa. 2000. FACT relieves DSIF/NELF-mediated inhibition of transcriptional elongation and reveals functional differences between P-TEFb and TFIIH. Mol. Cell 5:1067–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wada, T., T. Takagi, Y. Yamaguchi, D. Watanabe, and H. Handa. 1998. Evidence that P-TEFb alleviates the negative effect of DSIF on RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription in vitro. EMBO J. 17:7395–7403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wei, P., M. E. Garber, S. M. Fang, W. H. Fischer, and K. A. Jones. 1998. A novel CDK9-associated C-type cyclin interacts directly with HIV-1 Tat and mediates its high-affinity, loop-specific binding to TAR RNA. Cell 92:451–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wimmer, J., K. Fujinaga, R. Taube, T. P. Cujec, Y. Zhu, J. Peng, D. H. Price, and B. M. Peterlin. 1999. Interactions between Tat and TAR and human immunodeficiency virus replication are facilitated by human cyclin T1 but not cyclins T2a or T2b. Virology 255:182–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Winslow, B. J., R. J. Pomerantz, O. Bagasra, and D. Trono. 1993. HIV-1 latency due to the site of proviral integration. Virology 196:849–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yamaguchi, Y., T. Takagi, T. Wada, K. Yano, A. Furuya, S. Sugimoto, J. Hasegawa, and H. Handa. 1999. NELF, a multisubunit complex containing RD, cooperates with DSIF to repress RNA polymerase II elongation. Cell 97:41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zack, J. A., S. J. Arrigo, S. R. Weitsman, A. S. Go, A. Haislip, and I. S. Chen. 1990. HIV-1 entry into quiescent primary lymphocytes: molecular analysis reveals a labile, latent viral structure. Cell 61:213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]