Abstract

Objective:

To define perioperative and long-term outcome and prognostic factors in patients undergoing hepatectomy for liver metastases arising from noncolorectal and nonneuroendocrine (NCNN) carcinoma.

Summary Background Data:

Hepatic resection is a well-established therapy for patients with liver metastases from colorectal or neuroendocrine carcinoma. However, for patients with liver metastases from other carcinomas, the value of resection is incompletely defined and still debated.

Methods:

Between April 1981 and April 2002, 141 patients underwent hepatic resection for liver metastases from NCNN carcinoma. Patient demographics, tumor characteristics, treatment, and postoperative outcome were analyzed.

Results:

Thirty-day postoperative mortality was 0% and 46 of 141 (33%) patients developed postoperative complications. The median follow up was 26 months (interquartile range [IQR]) 10–49 months); the median follow up for survivors was 35 months (IQR 11–68 months). There have been 24 actual 5-year survivors so far. The actuarial 3-year relapse-free survival rate was 30% (95% confidence interval [CI], 21–39%) with a median of 17 months. The actuarial 3-year cancer-specific survival rate was 57% (95% CI, 48–67%) with a median of 42 months. Primary tumor type and length of disease-free interval from the primary tumor were significant independent prognostic factors for relapse-free and cancer-specific survival. Margin status was significant for cancer-specific survival and showed a strong trend for relapse-free survival.

Conclusions:

Hepatic resection for metastases from NCNN carcinoma is safe and can offer long-term survival in selected patients. Hepatic resection should be considered if all gross disease can be removed, especially in patients with metastases from reproductive tract tumors or a disease-free interval greater than 2 years.

Hepatic resection for metastases from noncolorectal, nonneuroendocrine carcinoma is safe and can offer long-term survival for selected patients, especially those with reproductive tract tumors, or a long disease-free interval after treatment of the primary tumor.

Resection of liver metastases arising from colorectal or neuroendocrine carcinoma is an effective treatment modality. For patients with liver metastases from colorectal cancer, surgical resection results in a 3-year survival rate of 30% to 61% and a 5-year survival rate of 16% to 51%, depending on patient selection.1–4 Five-year survival rates of 76% have been achieved with surgical resection in patients with hepatic neuroendocrine metastases, although some still consider these patients for liver transplantation.5,6 In contrast, the role of hepatectomy in patients with liver metastases from noncolorectal, nonneuroendocrine (NCNN) carcinoma is not well defined. Although the number of reports regarding this topic is increasing, most studies are limited by small patient numbers or the inclusion of patients with other tumor types besides carcinoma.7–15 We have recently reported our experience with liver resection for metastatic neuroendocrine tumors and sarcoma.5,16 In this study, we analyzed patients who underwent hepatic resection for metastases from NCNN carcinoma. The objectives were to define perioperative and long-term outcome and to define prognostic factors.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

One hundred forty-one patients with liver metastases from NCNN carcinoma who underwent partial hepatectomy at Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center between April 1981 and April 2002 were identified from the prospective database of the Hepatobiliary Service. Patients underwent surgical exploration if all disease (extra- and intrahepatic) was judged to be completely resectable and if the medical condition of the patient permitted a liver resection. Patients underwent routine staging using preoperative computed tomography (CT) scanning of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Further imaging such as brain CT or bone scan was performed at the discretion of the operating surgeon. Radiologic studies were reviewed at a multidisciplinary case management conference (held twice weekly since 1992) and additional imaging (such as magnetic resonance imaging) was obtained when necessary. Only patients with true hematogenous hepatic metastases were included. Patients with direct invasion of the liver by peritoneal implants (which is common in ovarian cancer) or by the primary tumor (such as with adrenocortical carcinoma) were excluded.

Some of the patients (n = 55) included in this study were reported in our initial published experience.17 From that report of 96 patients, we excluded the 27 patients with sarcoma and 1 patient with brain cancer. In addition, we excluded 13 others. We could not be certain that 5 patients truly had hematogenous metastases and not secondary infiltration of the liver, and we were not sure that 2 patients with metastases of unknown origin had secondary liver tumors and not primary liver tumors. We also excluded 2 patients with testicular cancer who had complete necrosis of their liver metastases in response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and 2 patients with gastric and 2 patients with uterine cancer because of incomplete follow up.

Patient demographics, tumor characteristics, treatment, and postoperative course were analyzed. The following factors were assessed specifically as prognostic factors: resection margin (R0: negative microscopic margin, R1: positive microscopic margin, R2: macroscopically visible residual tumor), gender, age, disease-free interval from the primary tumor, primary tumor histology, presence of extrahepatic disease, size of liver metastases, number of liver metastases, intrahepatic distribution (unilobar vs. bilobar), extent of hepatic resection (minor [<3 liver segments] vs. major), allogeneic blood transfusion, and postoperative complications. Patients were grouped according to primary tumor histology into the following categories: adrenocortical cancer, breast cancer, gastrointestinal cancers, reproductive tract cancers (testicular or gynecologic primary), melanoma, renal cancer, miscellaneous, and metastases of an unknown primary. The liver tumors of patients with an unknown primary underwent pathologic review to exclude the diagnosis of a primary hepatic neoplasm. In 40 patients, the following additional procedures were performed: lymph node dissection (n = 7), omentectomy (n = 2), orchiectomy (n = 1), bile duct resection (n = 2), inferior vena cava resection (n = 2), nephrectomy (n = 5), adrenalectomy (n = 8), lung resection (n = 4), partial colectomy (n = 2), resection of the diaphragm (n = 5), small bowel resection (n = 1), hysterectomy (n = 1), (partial) gastrectomy (n = 2), partial pancreatectomy (n = 3), and partial peritonectomy (n = 1). Some patients had more than 1 additional procedure. Overall, as a result of the great variability in the type, timing, and duration of chemotherapy, we did not include it as a factor in this analysis. The majority of patients with testicular cancer received preoperative chemotherapy as part of a multimodal treatment approach.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical computations were performed with the software package JMP (JMP, Cary, NC). The length of follow up was calculated from the date of hepatectomy at our institution. Disease-free interval was defined as the time period between resection of the primary tumor and the diagnosis of the liver metastasis. Survival was estimated according to the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank and Wilcoxon tests.18 Only death from cancer was considered an event in the analysis of cancer-specific survival. A multivariate proportional hazards model was built using the variables that had prognostic potential as suggested on univariate analysis (ie, P <0.1).19 Statistical significance was defined as P <0.05.

RESULTS

Clinical, Pathologic, and Treatment Factors

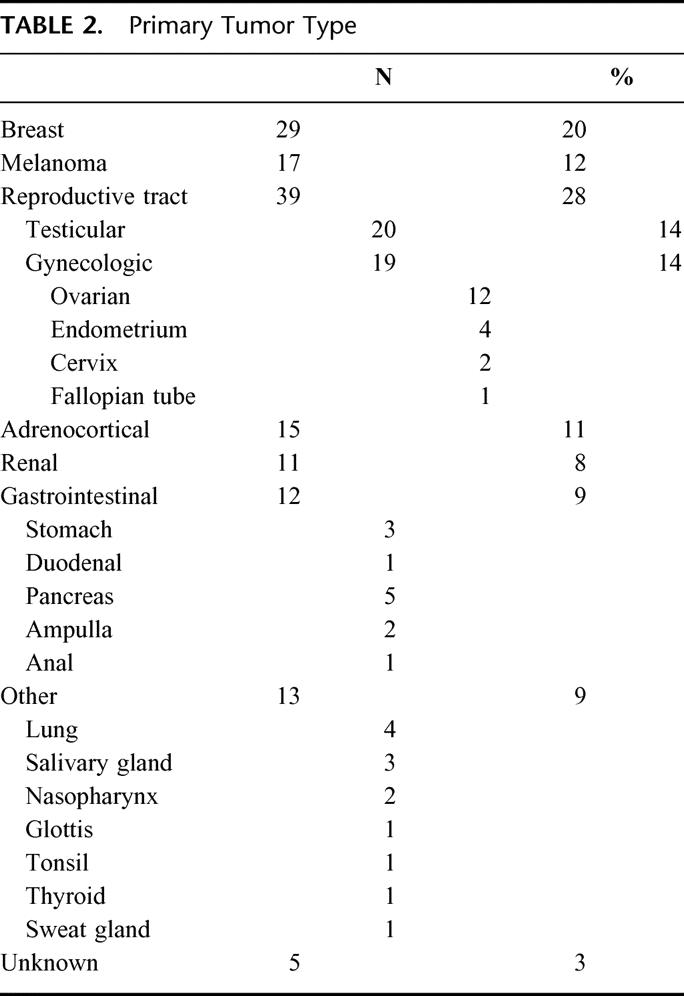

There were 141 patients who underwent laparotomy for potentially resectable liver metastases from NCNN carcinoma. Patient age ranged from 16 to 87 years, with a median age of 55. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the clinical and pathologic features of the patients. Metastases from reproductive tract carcinomas composed the largest patient subset (39 patients). Only a few patients had a primary tumor of the gastrointestinal tract. The following pathologic diagnoses accounted for the 5 patients with pancreatic cancer: papillary solid and cystic carcinoma (n = 3), cystadenocarcinoma (n = 1), and mucinous cystadenocarcinoma (n = 1). The median disease-free interval for patients with metachronous lesions (n = 102) was 41 months (interquartile range [IQR] 17–90).

TABLE 1. Clinical and Pathologic Factors

TABLE 2. Primary Tumor Type

The median operative time was 238 minutes (IQR 180–321); the median blood loss was 600 mL (IQR 250–1420). A complete macroscopic tumor resection was performed in 135 (96%) of the 141 patients. The treatment related factors are depicted in Table 3. Approximately 45% of patients underwent at least a hemihepatectomy. The median length of hospital stay was 9 days (IQR 7–12), 46 of 141 (33%) patients developed postoperative complications, and the 30-day mortality rate was 0%.

TABLE 3. Treatment

Follow Up and Outcome

The median follow up for all patients was 26 months with an IQR of 10–49 months, whereas the median follow up for surviving patients was 35 months (IQR 11–68 months). At the time of the last follow up, 47 patients (33%) had no evidence of disease, 19 (14%) were alive with disease, 73 (52%) had died of disease, and 2 patients (1%) had died of unknown causes.

Prognostic Factors for Relapse-Free Survival

The actuarial 3-year relapse-free survival was 30% (95% confidence interval [CI], 21–39%) with a median of 17 months. Table 4 depicts the univariate and multivariate analyses of prognostic factors for relapse-free survival. The Kaplan-Meier curves for margin status, primary tumor type, and disease-free interval are displayed in Figure 1 through 3. Disease-free interval longer than 24 months and primary tumor type (reproductive tract tumor) were favorable predictors of relapse-free survival on multivariate analysis. Margin status showed a trend, but failed to reach statistical significance (P = 0.08).

TABLE 4. Analysis of Prognostic Factors for Relapse-Free Survival

FIGURE 1. Survival after resection of hepatic metastases stratified according to margin status (R0: n = 116, R1: n = 19, R2: n = 6).

FIGURE 2. Survival after resection of hepatic metastases stratified according to primary tumor type (reproductive tract vs. nonreproductive tract tumors) (patients with R2 resection were excluded for relapse-free survival).

FIGURE 3. Survival after resection of hepatic metastases stratified according to disease-free interval (DFI) (patients with R2 resection were excluded for relapse-free survival).

Sixty-three percent of patients with reproductive tract tumors were free of recurrence 3 years after R0 resection and the median survival has not yet been reached. The length of the disease-free interval did not influence recurrence in this subgroup of patients on univariate analysis. There was no difference in 3-year relapse-free survival between patients with ovarian and testicular cancer (58 vs. 72%, P = not significant). In contrast, patients with nonreproductive tract primary tumors who underwent R0 resection had an actuarial 3-year survival rate of 30% with a median of 20 months if the disease-free interval was longer than 24 months and an actuarial 3-year survival rate of 5% and median of 8 months when the disease-free interval was ≤24 months (P <0.01).

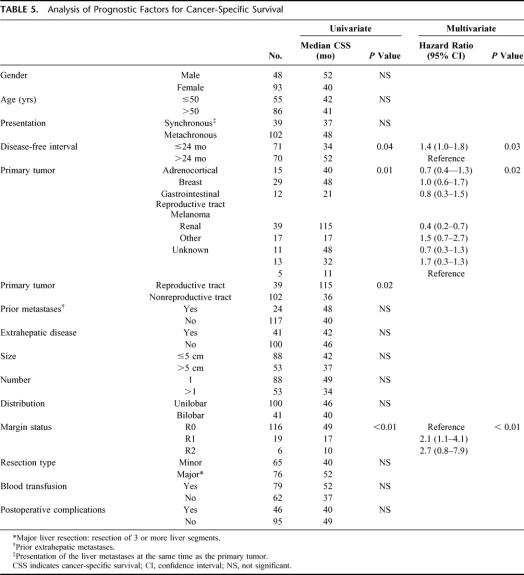

Prognostic Factors for Cancer-Specific Survival

So far, there have been 24 actual 5-year survivors with 49 patients still at risk. These 24 patients had the primary tumors in the adrenal gland (n = 3), breast (n = 5), cervix/endometrium (n = 2), skin (melanoma, n = 4), pancreas (n = 2), parotid (n = 1), kidney (n = 2), or testis (n = 5). One patient with an adrenocortical carcinoma is alive 11.5 years after liver resection. The actuarial 3-year cancer-specific survival rate was 57% (95% CI, 48–67%) with an estimated median of 42 months. Figures 1 through 3 show the Kaplan-Meier curves for margin status, primary tumor type, and disease-free interval. On multivariate analysis, negative margin status, disease-free interval longer than 24 months, and primary tumor type (reproductive tract tumor) were associated with an improved survival (Table 5).

TABLE 5. Analysis of Prognostic Factors for Cancer-Specific Survival

For patients with reproductive tract tumors who underwent R0 resection, the actuarial 3-year cancer-specific survival rate was 78% and the median has not yet been reached. The length of disease-free interval did not reach statistical significance in this subgroup of patients on univariate analysis. There was no difference in actuarial 3-year cancer-specific survival between patients with ovarian and testicular cancer (86% vs. 70%, P = not significant). For patients with nonreproductive tract primary tumors who underwent R0 resection and had a disease-free interval of >24 months (n = 41), the actuarial 3-year cancer-specific survival rate was 72% with a median of 64 months and there are 14 actual 5-year survivors so far. For similar patients who had a disease-free interval of ≤24 months (n = 40), the actuarial 3-year survival rate was 36% with an estimated median of 29 months (P <0.01) and only 3 actual 5-year survivors.

DISCUSSION

We evaluated the outcome and prognostic factors of patients undergoing hepatic resection for metastases from NCNN carcinoma. Hepatic resection was safe for these patients with no perioperative deaths and an acceptable complication rate. This report represents not only the largest published series so far, but focuses solely on NCNN carcinomas while excluding nonepithelial malignancies such as sarcoma. Because different primary tumor types have different underlying tumor biology, the ideal study should concentrate on only 1 tumor type to allow meaningful conclusions. This, however, is difficult as a result of the low patient numbers available for analysis. The importance of tumor type on prognosis in patients with liver metastases is clearly documented by the success of surgical resection of liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Patients with untreated but potentially resectable liver metastases of colorectal cancer have a 3-year survival rate of 20%, with less than 3% of patients surviving 5 years. In contrast, hepatectomy achieves a 3-year survival rate of 30% to 61% and a 5-year survival rate of 16% to 51% in patients with colorectal liver metastases.1–4 Based on these results and the improved safety of liver resection, the treatment of patients with liver metastases arising from primary colorectal cancers has shifted in recent years. Liver metastases of colorectal cancer are no longer viewed as indicators of untreatable widespread systemic disease, and in some patients, cure is still possible with surgery.

Two factors might be responsible for the favorable outcome of patients with liver metastases arising from colorectal cancer. First, the tumor biology of colorectal cancer may be different than that of other solid tumors. Hematogenous spread of tumor cells may be highly inefficient in colorectal cancer, with the majority of tumor cells dying before formation of clinically significant metastases. On the other hand, the liver may be the preferential organ for circulating colorectal cancer cells to implant because of the expression of particular adhesion molecules.20–22 The second factor may be the anatomic relationship of the large intestine to the liver with its venous drainage through the portal vein to the liver. The liver may be an effective filter for tumor cells by trapping them before they can escape into the systemic circulation. According to this theory, extrahepatic hematogenous metastases of colorectal carcinomas can only occur as metastases from established liver metastases.20 Both concepts are supported by clinical and experimental findings: tumor biology clearly is important as underlined by the fact that most of the prognostic factors after resection of colorectal liver metastases such as length of disease-free interval and nodal status of primary tumor are at least in part surrogates for tumor biology.4 The fact that circulating tumor cells are detected less frequently in the hepatic vein compared with the portal vein supports the notion that the liver is an effective filter for tumor cells.23

These concepts are important when discussing surgical resection of noncolorectal liver metastases. Anatomic factors are different than those seen in colorectal cancer, with the exception of gastrointestinal primary tumors. Liver metastases from nongastrointestinal cancers, by definition, indicate systemic tumor spread. Selection of patients with favorable tumor biology seems therefore to be of major importance to select patients who may benefit the most from hepatic resection. Although tumor biology depends on the primary tumor type, within a particular histology, there may be more favorable patient subsets. The importance of tumor type is documented by the favorable outcome of patients with liver metastases from primary neuroendocrine tumors, with reported 5-year survival rates of 76%.5 Primary tumor type was an important prognostic factor in the current study, because relapse-free and cancer-specific survival for patients with reproductive tract primary tumors was significantly longer when compared with that of patients with nonreproductive tract primary tumors (Fig. 2; Tables 4 and 5). Differences in outcome for the subsets of nonreproductive tract tumors might reach statistical significance after a larger patient cohort is obtained. Our observation of an improved outcome for patients with reproductive tract primaries is in accordance with earlier publications.12,17

The disease-free interval between treatment of the primary tumor and the development of liver metastasis is also viewed as a surrogate marker for tumor biology. A longer disease-free interval is believed to indicate less aggressive tumor biology. This notion is supported by the results of this study because patients with a disease-free interval over 24 months had a longer relapse-free and cancer-specific survival after hepatectomy (Fig. 3). Similar results were reported previously in patients undergoing hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer, sarcoma, and NCNN primaries.4,9,16,17

The third factor that has to be taken into account in considering hepatic resection for a patient with NCNN metastases is the likelihood of achieving a microscopically complete tumor resection. In this study, resection margin showed a strong trend as a prognostic factor for relapse-free survival and showed statistical significance for cancer-specific survival, which is in agreement with earlier studies.17 Interestingly, the presence of extrahepatic disease was not an independent prognostic factor in this study, provided that a complete resection was performed. The possibility of achieving a negative margin clearly depends on tumor-related factors as well as surgical expertise and is of paramount importance.

Based on our results, primary tumor type and length of disease-free interval are valid criteria to assess the potential outcome after a planned hepatic resection for patients with metastatic NCNN tumors. Patients with a primary reproductive tract tumor will have a favorable outcome with an actuarial 3-year cancer-specific survival of 78% after R0 resection. In the group of patients with primary nonreproductive tract tumors, survival after R0 resection depends on the length of the disease-free interval. Patients with a disease-free interval of ≤24 months have an actuarial 3-year survival rate of 36%, but only 5% are free of relapse after 3 years. However, patients with a nonreproductive tract primary and a disease-free interval of >24 months have an actuarial 3-year cancer-specific survival rate of 72% and an actuarial 3-year relapse-free survival rate of 30%. There were 14 actual 5-year survivors in this group, an outcome likely the result of resection of the hepatic metastases. The outcome for the latter group compares favorably with the published results of hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer and demonstrates the impact of selecting patients with favorable tumor biology.4 The extent of selection is also apparent by the relative infrequency of partial hepatectomy for NCNN metastases at our institution. From July 1985 to October 1998, we performed hepatectomy for 1001 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer compared with the 141 patients reported in this study over a 21-year time period.4 Clearly, preoperative staging with modern imaging modalities is of paramount importance for proper patient selection and exclusion of patients with unresectable disease.

We conclude that hepatic resection for metastatic NCNN carcinomas is safe and is associated with a favorable outcome in highly selected patients. Because hepatic resection is the only modality offering a potential cure, this option should be contemplated in these patients.

Footnotes

*Present address: Department of Surgery, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany.

Reprints: Ronald P. DeMatteo, MD, Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center, Box 203, 1275 York Avenue, New York, NY 10021. E-mail: dematter@mskcc.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fong Y, Cohen AM, Fortner JG, et al. Liver resection for colorectal metastases. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:938–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scheele J, Stang R, Altendorf-Hofmann A, et al. Resection of colorectal liver metastases. World J Surg. 1995;19:59–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schlag P, Hohenberger P, Herfarth C. Resection of liver metastases in colorectal cancer—competitive analysis of treatment results in synchronous versus metachronous metastases. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1990;16:360–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fong Y, Fortner J, Sun RL, et al. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 1999;230:309–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chamberlain RS, Canes D, Brown KT, et al. Hepatic neuroendocrine metastases: does intervention alter outcomes? J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190:432–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lehnert T. Liver transplantation for metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma: an analysis of 103 patients. Transplantation. 1998;66:1307–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamada H, Katoh H, Kondo S, et al. Hepatectomy for metastases from non-colorectal and non-neuroendocrine tumor. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:4159–4162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karavias DD, Tepetes K, Karatzas T, et al. Liver resection for metastatic non-colorectal non-neuroendocrine hepatic neoplasms. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2002;28:135–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laurent C, Rullier E, Feyler A, et al. Resection of noncolorectal and nonneuroendocrine liver metastases: late metastases are the only chance of cure. World J Surg. 2001;25:1532–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benevento A, Boni L, Frediani L, et al. Results of liver resection as treatment for metastases from noncolorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2000;74:24–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwartz SI. Hepatic resection for noncolorectal nonneuroendocrine metastases. World J Surg. 1995;19:72–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elias D, Cavalcanti de Albuquerque A, Eggenspieler P, et al. Resection of liver metastases from a noncolorectal primary: indications and results based on 147 monocentric patients. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takada Y, Otsuka M, Seino K, et al. Hepatic resection for metastatic tumors from noncolorectal carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:83–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goering JD, Mahvi DM, Niederhuber JE, et al. Cryoablation and liver resection for noncolorectal liver metastases. Am J Surg. 2002;183:384–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemming AW, Sielaff TD, Gallinger S, et al. Hepatic resection of noncolorectal nonneuroendocrine metastases. Liver Transpl. 2000;6:97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeMatteo RP, Shah A, Fong Y, et al. Results of hepatic resection for sarcoma metastatic to the liver. Ann Surg. 2001;234:540–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrison LE, Brennan MF, Newman E, et al. Hepatic resection for noncolorectal, nonneuroendocrine metastases: a fifteen-year experience with ninety-six patients. Surgery. 1997;121:625–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc (B). 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sugarbaker PH. Metastatic inefficiency: the scientific basis for resection of liver metastases from colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol Suppl. 1993;3:158–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiss L. Metastatic inefficiency. Adv Cancer Res. 1990;54:159–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mizuno N, Kato Y, Izumi Y, et al. Importance of hepatic first-pass removal in metastasis of colon carcinoma cells. J Hepatol. 1998;28:865–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koch M, Weitz J, Kienle P, et al. Comparative analysis of tumor cell dissemination in mesenteric, central and peripheral venous blood in patients with colorectal cancer. Arch Surg. 2001;136:85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]