Abstract

Objective:

To identify factors that predict fourth- and fifth-year surgical resident satisfaction of attending teaching quality.

Summary Background Data:

With the training of surgical residents undergoing major changes, a key issue facing surgical educators is whether high-quality surgeons can still be produced. Innovative techniques (eg, computer simulation surgery) are being developed to substitute partially for conventional teaching methods. However, an aspect of training that cannot be so easily replaced is the faculty–resident interaction. This study investigates resident perceptions of attending teaching quality and the factors associated with this faculty–resident interaction to identify predictors of resident educational satisfaction.

Methods:

A national survey of clinical fourth- and fifth-year surgery residents in 125 academically affiliated general surgery training programs was performed. The survey contained 67 questions and addressed demographics, hospital, and service characteristics, as well as surgery, education, and clinical care-related factors. Univariate analyses were performed to describe the characteristics of the sample; multivariate analyses were performed to evaluate the factors associated with resident educational satisfaction.

Results:

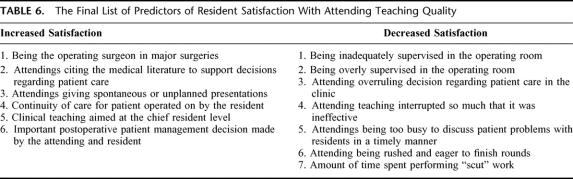

The response rate was 61.5% (n = 756). Average age was 32 years; most were male (79%), white (72%), and married (69%); 42% had children. Ninety-five percent of respondents graduated from U.S. medical schools, and the average debt was $80,307. Of 20 potentially mutable factors, 6 variables had positive associations with resident education satisfaction and 7 had negative associations. Positive factors included the resident being the operating surgeon in major surgeries, substantial citing of evidence-based literature by the attending, attending physicians giving spontaneous or unplanned presentations, increasing the continuity of care, clinical teaching aimed at the chief resident level, and having clinical decisions made together by both the attending and resident. There were 7 negative factors such as overly supervising in surgery, being interrupted so much that teaching was ineffective, and attending physicians being rushed and/or eager to finish rounds.

Conclusion:

This study identifies several factors that were associated with resident educational satisfaction. It offers the perspective of the learners (ie, residents) and, importantly, highlights mutable factors that surgery faculty (and departments) may consider changing to improve surgery resident education and satisfaction. Improving such satisfaction may help to produce a better product.

Using a national survey of clinical fourth- and fifth-year surgery residents in 125 academically affiliated general surgery training programs, we identify factors that predict resident satisfaction of attending teaching quality. Six variables had positive associations with resident education satisfaction and 7 had negative associations.

The training of surgical residents is undergoing major changes in the face of 2 recent factors. First, the 80-hour workweek, which began as of July 1, 2003, now measures and limits time spent by residents in the hospital.1–3 As such, training and education issues like continuity of care, surgical caseloads, and faculty–resident interactions may be affected.4–7 The second factor is the increased clinical load for the “teachers,” ie, the surgical faculty. Concomitant with the increases in managed care, conservative estimates report a 25% increase in surgical work.8 As faculty surgeons operate more, the training and development of the residents may also be affected.9

A key issue facing surgical educators is whether high-quality surgeons can still be produced given these constraints. Innovative techniques such as teaching over the Internet and computer simulation surgery that are being developed may be able to substitute partially for conventional teaching methods.10–14 However, it is not clear that they will be a complete substitute. In particular, an aspect of surgical training that cannot be so easily replaced is the faculty–resident interaction. The interaction between faculty and residents—both in the one-on-one setting (eg, in the operating room) and in the team setting (eg, attending rounds)—is likely paramount in both operative and nonoperative training. Furthermore, faculty as role models and mentors for the medical students have been instrumental in attracting the “best and the brightest” into surgery.15–20 An important question for surgical educators, therefore, is how to optimize such faculty interactions with the residents and medical students in the current climate.

To address this issue for residents, this study identifies factors that predict fourth- and fifth-year surgery resident educational satisfaction with attending teaching quality. Satisfaction is likely an important outcome measure because it has been shown in other healthcare training fields to be a meaningful indicator of quality processes.21 Although this report is novel in part because it offers the perspective of learners, it more importantly serves to highlight mutable factors that surgery faculty (and departments) may consider changing to improve surgery resident satisfaction and, possibly, education.

METHODS

Sample Selection

This study is based on a national survey of clinical fourth- and fifth-year surgery residents in the United States. We obtained from the American Medical Association (AMA) contact and program information on residents in 125 academically affiliated general surgery residency programs. (These programs identified themselves as “academically affiliated” as a result of their close affiliation with medical schools or university teaching hospitals.) The original sample consisted of all 1334 fourth- and fifth-year surgery residents listed in these programs by the AMA for the academic year 2001–2002.

Survey Design and Administration

The survey instrument was developed by a team of researchers and physicians and was based on literature review, resident focus groups, and reviews of the relevant policies of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, the resident review committee (RRC), and expert opinion. The survey contained 67 questions and was designed to take 30 minutes to complete. Cognitive testing of the survey was performed for understandability and accuracy of response by the RAND Survey Research Group.

The survey was administered by mail in the Spring of 2002. Response enhancement techniques included advance notification, multiple mailings, telephone follow ups, and a monetary incentive for completing the survey.

Variables

Several categories of variables were collected in the survey, 2 of which were specifically designed to describe the respondents and the setting in which they worked. Resident demographics were collected to describe the cohort and included age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, number of children, and educational debt. Hospital and service characteristics were also collected and were reported based on the respondents' most recent service or rotation. This group of variables included the surgical discipline that was emphasized during the most recently completed rotation (eg, endocrine, vascular), hospital setting (eg, university, Veterans Affairs), and components of the surgery team (eg, number of attending physicians, fellows, interns).

In addition, 3 categories of variables related to aspects of residency training were collected. Again, in all questions relating to residency training, respondents were instructed to provide answers that were specific to their most recently completed rotation.

The first category consisted of surgery-related measures and included the total number of surgeries performed, the total number of surgeries as operating surgeon, the percentage of major surgeries in which the residents were the operating surgeon, the percentage of surgeries in which the residents performed the crucial parts, the percentage of time in which attending physicians were present during the crucial parts of major surgeries, and how frequently the residents felt they were inadequately or overly supervised. (All variables measuring frequency had the following 5 response categories: “never or almost never,” “rarely,” “sometimes,” “often,” and “almost always or always.” For ease of analysis and presentation, these 5 categories were collapsed to 3: “never, almost never, or rarely,” “sometimes,” and “often, almost always, or always.”)

Education-related measures targeted attending-specific factors and included the frequency with which attending physicians cited the medical literature to support patient care decisions, gave spontaneous or unplanned presentations, discussed how to evaluate patients as suitable candidates for surgery, discussed the likely long-term outcomes of surgery for patients seen in the clinic, aimed their teaching at the chief resident level, seemed rushed and eager to finish rounds, and the frequency in which the faculty were called away or interrupted so that their teaching was ineffective.

The third category of variables was composed of clinical care-related measures that included the amount of time spent by residents in clinic actually seeing patients, the amount of administrative or “scut” work residents performed, whether patient management was generally performed by attending physicians alone versus residents, and the frequency with which attending physicians overruled the resident's decisions or were too busy to discuss patient problems with residents in a timely manner.

The outcome variable for this study was resident satisfaction with faculty teaching. This item was measured by response to the following question: “Thinking about all your experiences (in the operating room, on the wards, and in the clinic) during your most recently completed rotation, how satisfied were you with the quality of the teaching by attending physicians?” Response categories were: “very dissatisfied,” “dissatisfied,” “neither dissatisfied nor satisfied,” “satisfied,” and “very satisfied.” These 5 responses were collapsed to 2 (“satisfied” vs. “neutral or dissatisfied”) for ease of analysis and interpretation.

Analysis

Descriptive analyses (means and frequencies) were performed to describe the characteristics of the sample. Multivariate analyses were performed to evaluate the extent to which the surgery, education, and clinical care-related measures were related to resident satisfaction after controlling for resident demographics, hospital and service characteristics. The multivariate analyses consisted of logistic regressions in which the dichotomous dependent variable (“satisfied” with the quality of teaching by attending physicians vs. “neutral or dissatisfied”) was regressed on the set of control variables and 1 of the 3 sets of variable categories (ie, surgery, education, and clinical care-related measures) at a time.

RESULTS

The response rate, adjusted for invalid sample (ie, 105 people who left their program) was 61.5% (n = 756).

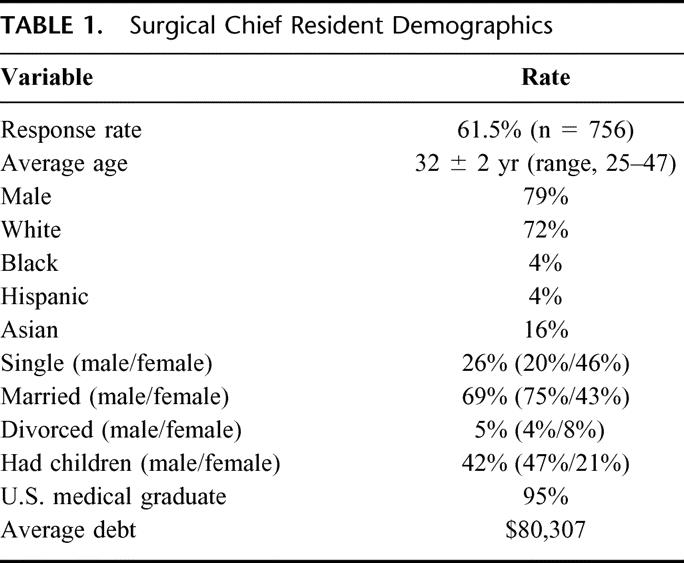

Resident Demographics

The average age of the clinical fourth- and fifth-year residents in our survey was 32 years; most were male (79%), white (72%), and married (69%); and 42% had children. The average number of children for male and female residents was 1.7 and 1.6, respectively. Ninety-five percent of respondents graduated from U.S. medical schools, and the average debt was $80,307 (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Surgical Chief Resident Demographics

Forty-two percent of respondents planned to finish their surgery residency in 5 years without taking time to perform nonclinical work such as research. Ten percent reported having taken 1 to 6 months to perform nonclinical work during their residency up to the point at which they were surveyed, 20% reported between 7 and 12 months, 22% reported 13 to 24 months, and 6% reported more than 2 years.

Hospital and Service Characteristics

On their most recently completed rotation, respondents tended to perform procedures in general surgery (56%), vascular surgery (23%), and trauma (21%). Most worked in a university hospital (55%), a private (nonuniversity, non-HMO) hospital (19%), or a county/city hospital (17%).

The average number of attending physicians per surgery service was 5.2, whereas the average number of attending physicians who rounded with the residents was 3.4. The average number of fellows on a service was 0.3, and the number of other clinical R4 or R5 residents was 0.6. The reported average daily census for primary patients was 18, whereas the average number of consults followed by the service was 8.

Surgery-Related Variables

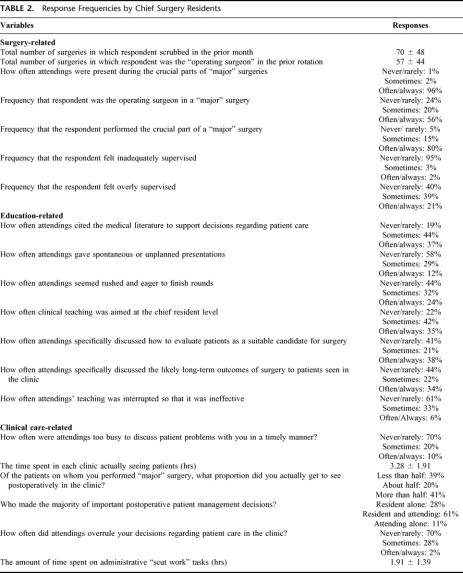

The survey covered a number of detailed issues regarding the overall operative experiences of the residents. Response frequencies are in Table 2. To highlight some important items, the mean number of surgeries per week in which the respondent “scrubbed in” was 8 and respondents reported spending an average of 26 hours per week in the operating room. In 80% of cases, the respondent was the operating surgeon. Fifty-eight percent of the residents reported that they almost always or always performed the crucial parts of major surgeries, whereas 15% reported sometimes, rarely, or never performing the crucial part. Eighty-eight percent of respondents reported that attending physicians were present almost always or always during the crucial parts of major surgeries. Ninety-five percent of the residents rarely or never felt inadequately supervised during major surgeries; however, 40% sometimes felt overly supervised, and 21% often or always felt overly supervised.

TABLE 2. Response Frequencies by Chief Surgery Residents

When asked to evaluate the best instructional methods for learning surgical technique, the top 3 methods ranked most useful were teaching by attending physicians in the operating room, reading in texts/atlases, and teaching by the attending outside the operating room.

Education-Related Variables

Less than 40% of respondents reported that faculty often cited the medical literature to support their decisions in patient care. Also, over 50% reported that attending physicians rarely offered spontaneous or unplanned presentations. Almost 25% of respondents reported that attending physicians seemed rushed and eager to finish rounds, and over 30% felt that attending physicians were interrupted so much that their teaching was ineffective. Regarding time allotments, the fourth- and fifth-year resident respondents reported spending an average of 6 hours per week in formal lectures, 6 hours per week reading surgery-related materials, and just under 2 hours per day teaching junior residents and medical students. Also, on average, they reported that there were 2 attending teaching rounds per week, with each session lasting approximately 1 hour. Additional findings are also in Table 2.

Clinical Care-Related Variables

Seventy percent of respondents reported that attending physicians were never or rarely too busy to discuss patient problems in a timely manner. Moreover, the majority of important postoperative patient management decisions were made with the resident and attending (61%) versus the attending alone (11%). With regard to continuity of care of patients on whom they performed major surgery, 20% of respondents saw about half in clinic postoperatively; 41% reported they saw more than half, and 39% reported seeing less than half. Respondents reported spending 3 hours per day rounding and 3 hours per day performing administrative work (ie, “scut” work). Finally, they reported being completely “off beeper” an average of 34 hours per week. Additional findings for this category are in Table 2.

Predictors of Resident Satisfaction With Attending Teaching

We now present results from the logistic analysis of factors that predict resident satisfaction with attending teaching. We group the discussion of predictors into 3 areas (surgery, education, and clinical care-related) to facilitate presentation.

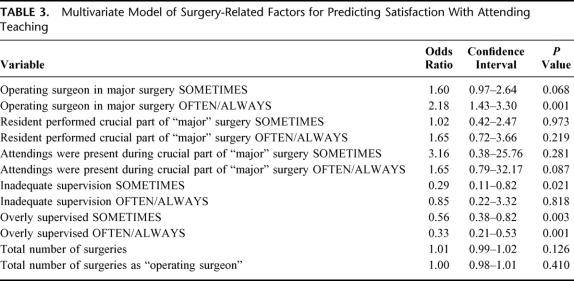

Of 7 possible surgery-related variables, 3 were statistically significant (P <0.05). The variable associated with increased satisfaction was being the operating surgeon in major surgeries (odds ratio [OR], 2.17; P = 0.0001), whereas 2 variables associated with decreased satisfaction were inadequate supervision in the operating room (OR, 0.29; P = 0.021) and being overly supervised in the operating room (OR, 0.33; P = 0.001) (Table 3).

TABLE 3. Multivariate Model of Surgery-Related Factors for Predicting Satisfaction With Attending Teaching

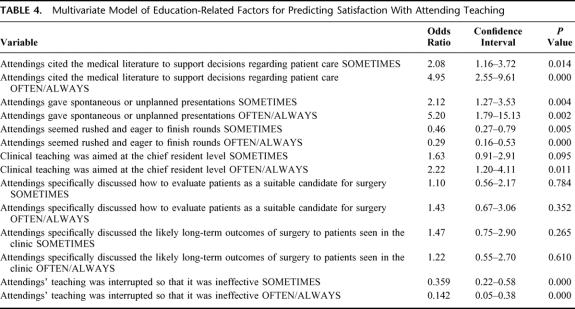

Three education-related variables were statistically associated with increased satisfaction: the attending citing the medical literature to support patient care decisions (OR, 4.95; P <0.001), more spontaneous or unplanned presentations by the attending (OR, 5.20; P = 0.002), and more teaching to the level of the chief resident (OR, 2.22; P = 0.011). Two variables were associated with decreased satisfaction; they included having attending physicians' teaching interrupted so much that it was ineffective (OR, 0.14; P = 0.001) and having attending physicians that seemed rushed and eager to finish rounds (OR, 0.29; P <0.001) (Table 4).

TABLE 4. Multivariate Model of Education-Related Factors for Predicting Satisfaction With Attending Teaching

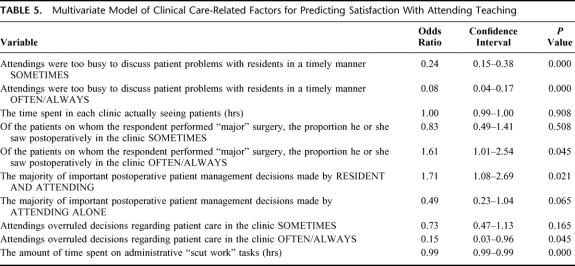

The clinically-related variable associated with increased satisfaction was increased continuity of care (OR, 1.61; P = 0.045). Another variable that increased satisfaction was having important management decisions being made by the attending and resident together (OR, 1.71; P = 0.021). Regarding factors associated with lower satisfaction, 2 noteworthy variables were attending physicians being too busy to discuss particular clinical (patient) problems in a timely manner (OR, 0.08; P = 0.001) and attending physicians alone making the majority of important patient management decisions (OR, 0.50; P = 0.06) (Table 5).

TABLE 5. Multivariate Model of Clinical Care-Related Factors for Predicting Satisfaction With Attending Teaching

Two additional factors associated with decreased educational satisfaction were having the attending overrule decisions regarding patient care in the clinic and the amount of time spent performing “scut” work.

Table 6 is a summary list of all predictors that significantly influenced resident satisfaction with faculty teaching quality.

TABLE 6. The Final List of Predictors of Resident Satisfaction With Attending Teaching Quality

DISCUSSION

Given the 80-hour workweek mandate, as well as the current workload (and future projected) increases for surgical faculty, the training of surgical residents is undergoing significant change. Less time for clinical care, less resident continuity of care, and less time for teaching have all been reported. Moreover, such changes may have direct and indirect effects on the future surgical workforce. Specifically, there has been concern in the recent past when several highly reputable surgery programs did not completely fill their residencies. Many reasons were cited, with one repeatedly being that residents were unhappy with their training and education. All of these factors point to the need for continued attention to the quality of training programs and to the importance of actions that can preserve high-quality education in the face of significant challenges.

The findings of the analyses of factors associated with higher satisfaction with attending teaching are especially important because with the decreased time for attending–resident interactions; the available time needs to be optimized. This survey suggests that several specific and mutable attending practices related to surgical, educational, and clinical care are associated with satisfaction. In all, 13 individual variables were identified, 6 of which were associated with increased satisfaction and 7 of which were associated with decreased satisfaction.

A few surgery-related items shown to have strong associations with resident satisfaction validated what many surgery programs have targeted as a training priority, that is, graduated responsibility in the operating room. Being the operating surgeon in a “major” surgical case was the respondents' most important factor in their rating of satisfaction with quality of education. Being inadequately supervised as well as being overly supervised negatively impacted satisfaction. Fortunately, inadequate supervision was reported to occur less than 5% of the time. Being overly supervised was reported to occur more frequently, more than 20% of the time. This issue is a difficult one because although it is important for faculty to remain cognizant of how “taking over” the case from residents may affect their learning experience, the faculty must concomitantly provide the highest quality of care to their patients. Achieving both tasks simultaneously may require a new model such as having the resident increasingly practice advanced or complex surgical techniques with simulators so that the residents become more proficient at surgery; or, possibly more of an apprenticeship-type model would help facilitate resident development and operating because greater “continuity” of teaching with 1 or 2 faculty would result. Our survey shows an average of more than 5 attending faculty surgeons per service.

Three education-related factors influencing resident satisfaction are interesting and fortunately also mutable. First, attending physicians that often or always cited the medical literature to support patient care decisions tended to have higher satisfaction ratings. As evidence-based surgery is becoming increasingly touted, faculty should attempt to increase the use and discussion of the literature. Increasingly, more evidence-based sources are addressing topics that are appropriate to the surgical audience. Second, attending physicians who gave spontaneous, unplanned presentations had higher satisfaction ratings. This is an area where much improvement may be made because almost 60% of the respondents reported that attending physicians never or rarely gave spontaneous presentations. Third, the manner in which teaching is performed also has a strong association with resident teaching satisfaction. Attending physicians who seemed rushed and eager to finish rounds and whose teaching was significantly interrupted lowered satisfaction scores. Available evidence suggests that we are in an era of increasing time demands in which more patients are being seen and increasing clinical loads are resulting. Although time demands are not easy to resolve, our findings show that these demands are affecting the quality of teaching and educational satisfaction. Similar to the stance that quality-of-care improvement relies on better systems, so too it seems that the educational shortcomings are associated with systems problems. This dilemma is not a new one; however, to reiterate, education is clearly affected (negatively) in the current climate and system.

In addition to surgery- and education-related items, there were also clinical care-related variables associated with resident satisfaction. Having attending physicians who were often or always too busy to discuss patient problems in a timely manner is associated with lower satisfaction ratings. Fortunately, the reported prevalence of this was low at 10%. Continuity of care has always been identified as a priority and was positively associated with higher satisfaction. The fact that almost half of the respondents saw less than 50% of the patients that they operated on in a postoperative clinic is cause for concern. Moreover, this survey was administered before the formal implementation of the 80-hour workweek. If and how this percentage will change now that the 80-hour workweek mandate has been put into effect needs to be addressed. Finally, the way in which patient care decisions were made was associated with teaching satisfaction. Residents need to be involved in patient care decision-making, but also need the input of their teachers. Resident satisfaction was higher when the majority of important postoperative patient management decisions were made by the resident and attending than when decisions were made by the resident alone. Alternatively, having the majority of decisions made by the attending alone lowered satisfaction. Although it is encouraging that more than 60% of the respondents reported that the majority of important clinical care decisions were made by the resident and attending together, there is room for substantial improvement. It will be important to see how the process of patient care decision-making will change with the likely increased resident cross coverage as a result of the 80-hour workweek mandate.

Although this study has several unique advantages, there are caveats to keep in mind. First, the data are obtained from a survey of residents, so these findings are based on resident perceptions. Although, on the one hand, faculty may believe that some of the perceptions are inaccurate or unjustified, they are the beliefs of the residents and should be respected and addressed in that regard. Second, these findings are based on the perceptions of fourth- and fifth-year residents only and may not be representative of the perceptions of more junior residents or surgeons who have completed their residency.22 It is evident that the focus of priorities of a surgeon often changes during residency and maybe more so afterward. For example, operating in major cases was deemed to be one of the top predictors of teaching satisfaction, whereas learning to evaluate patients as appropriate and suitable candidates for surgery was not important. However, this latter factor will likely become substantially more meaningful when these respondents begin their own practice and have the ultimate responsibility for outcomes.

Third, this study only surveyed residents from university-affiliated programs, however, the face validity of the findings likely allow for the results to be applied to nonuniversity programs. Finally, a response bias may be possible given the 61.5% response rate. However, the collected data are demographically and geographically representative for the respondents and training programs, respectively.

In summary, this national study of more than 750 fourth- and fifth-year surgery residents identifies a number of factors that were associated with better resident satisfaction regarding the quality of attending teaching. Furthermore, many of the factors are mutable in that certain identified areas for improvement may be influenced to increase satisfaction. Specifically, the findings suggest that faculty should continue to allow residents to perform the important steps in the operations but without being overly supervised. In addition, faculty should try to give spontaneous and evidence-based teaching presentations that are not rushed or interrupted by other duties. Finally, continuity of care and shared patient management decision-making should continue to be a priority, particularly in light of the new resident work hour changes. Improving resident satisfaction may not only help produce a better product, but may also help encourage more medical students to enter surgery and, as a possible byproduct, increase the satisfaction of the faculty.23

Footnotes

Reprints: Clifford Ko, MD, MSHS, UCLA Department of Surgery, 10833 LeConte Ave., 72-215 CHS, Los Angeles, CA 90095. E-mail: cko@mednet.ucla.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Organ CH. The generation gap in modern surgery. Arch Surg. 2002;137:250–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenfield LJ. Limiting resident duty hours. Am J Surg. 2003;185:10–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson T. Limitations on residents' working hours at New York teaching hospitals: a status report. Acad Med. 2003;78:3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barden CB, Specht MC, McCarter MD, et al. Effects of limited work hours on surgical training. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;195:531–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whang EE, Mello MM, Ashley SW, et al. Implementing resident work hour limitations. Lessons from the New York State Experience. Ann Surg. 2003;237:449–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peterson LA, Brennan TA, O'Neil AC, et al. Does housestaff discontinuity of care increase the risk for preventable adverse events? Ann Intern Med 1994;121:866–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laine C, Goldman L, Soukup JR, et al. The impact of a regulation restricting medical house staff working hours on the quality of patient care. JAMA. 1993;269:374–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Debas HT. Impact of the health care crisis on surgery. Arch Surg. 2001;136:158–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mallon WT, Jones RF. How do medical schools use measurement systems to track faculty activity and productivity in teaching? Acad Med. 2002;77:115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Powers TW, Murayama KM, Toyama M, et al. Housestaff performance is improved by participation in a laparoscopic skills curriculum. Am J Surg. 2002;184:626–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parsa CJ, Organ CH, Barkan H. Changing patterns of resident operative experience from 1990 to 1997. Arch Surg. 2000;135:570–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grantcharov TP, Rosenberg J, Pahle E, et al. Virtual reality computer simulation. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:242–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shapiro SJ, Gordon LA, Daykhovsky L, et al. The laparoscopic hernia trainer. The role of a life-like trainer in laparoendoscopic education. Endosc Surg Allied Technol. 1994;2:66–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosser JC, Babriel N, Herman B, et al. Telementoring and teleproctoring. World J Surg. 2001;25:1438–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neumayer LA, Cochran A, Melby S, et al. The state of general surgery residency in the United States: Program director perspectives, 2001. Arch Surg. 2002;137:1262–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bland KI, Isaacs GI. Contemporary trends in student selection of medical specialties. Arch Surg. 2002;137:259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zinner MJ. Surgical residencies: are we still attracting the best and the brightest? Bull Am Coll Surg. 2002;87:20–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Debas HT. Surgery: a noble profession in a changing world. Ann Surg. 2002;236:263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erzurum VZ, Obermeyer RJ, Fecher A, et al. What influences medical students' choice of surgical careers. Surgery. 2000;128:253–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linzer M, Beckman M. Honor our role models. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:76–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saarikoski M. Mentor relationship as a tool of professional development of student nurses in clinical practice. Int J Psychiatr Nurs Res. 2003;9:1014–1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gabram SGA, Hoenig J, Schroeder JW, et al. What are the primary concerns of recently graduated surgeons and how do they differ from those of the residency training years? Arch Surg. 2001;136:1109–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nadol JB Jr. Training the physician-scholar in otolaryngology–head and neck surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;121:214–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]