Abstract

Objective:

To determine if an aggressive surgical approach, with an increase in R0 resections, has resulted in improved survival for patients with gallbladder cancer.

Summary Background Data:

Many physicians express a relatively nihilistic approach to the treatment of gallbladder cancer; consensus among surgeons regarding the indications for a radical surgical approach has not been reached.

Methods:

A retrospective review of all patients with gallbladder cancer admitted during the past 12 years was conducted. Ninety-nine patients were identified. Cases treated during the 12-year period 1990 to 2002 were divided into 2 time-period (TP) cohorts, those treated in the first 6 years (TP1, N = 35) and those treated in the last 6 years (TP2, N = 64).

Results:

Disease stratification by stage and other demographic features were similar in the 2 time periods. An operation with curative intent was performed on 38 patients. Nine (26%) R0 resections were performed in TP1 and 24 (38%) in TP2. The number of liver resections, as well as the frequency of extrahepatic biliary resections, was greater in TP2 (P < 0.04). In both time periods, an R0 resection was associated with improved survival (P < 0.02 TP1, P < 0.0001 TP2). Overall survival of all patients in TP2 was significantly greater than in TP1 (P < 0.03), with a median survival of 9 months in TP1 and 17 months in TP2. The median 5-year survival in TP1 was 7%, and 35% in TP2. The surgical mortality rate for the entire cohort was 2%, with a 49% morbidity rate.

Conclusions:

A margin-negative, R0 resection leads to improved survival in patients with gallbladder cancer.

A large experience with gallbladder carcinoma at a North American center is described. Aggressive surgery which ensures microscopic and macroscopic negative resection margins has led to improved long-term survival.

The surgical treatment of gallbladder cancer has traditionally been viewed with nihilism due to poor survival results. In 1978, a review of nearly 6000 cases1 revealed a 5% 5-year survival rate with a median survival of between 5 and 8 months. Recent publications during the 1990s have shown the same poor results, with 5% and 12% 5-year survival rates reported from France and Australia.2,3 Factors contributing to these dismal outcomes include the anatomic proximity of the gallbladder to the porta hepatis and the aggressive biologic nature of this cancer. Furthermore, direct extension of the tumor into the liver, the structures of the hepatoduodenal ligament, as well as organs in close proximity such as the duodenum, the hepatic flexure of the colon, and the pancreas, contribute to technical challenges in achieving a margin negative, potentially curative (R0) resection.

However, improvements in surgical and anesthetic techniques over the last 10 to 15 years have made it possible to safely perform large, extensive liver resections with decreased morbidity and low mortality, particularly in high-volume centers.4–6 Reports of improved outcomes from Japanese centers that have adopted an aggressive surgical approach to gallbladder cancer have led to a reappraisal of surgical strategy for this disease in North America. Some hepatobiliary specialty units have broadened an already aggressive approach that includes liver resection in combination with resection of the gallbladder, bile duct, and regional lymphatics by including pancreaticoduodenectomy. The addition of pancreaticoduodenectomy allows complete resection of the extrahepatic biliary tree and its regional lymph node drainage to obtain an R0 resection that would not otherwise be possible.7–19 In these published reports, 78 pancreaticoduodenectomies (6 in North American centers, the others Japanese) were performed to obtain negative margins in cases with advanced disease and to clear the draining nodal basin. Moreover, these series report 18 patients with stage IV disease who have actually survived 5 years after radical resection. Whether the fact that some node-positive 5-year survivors have been reported in Japan, while none have been identified in North America, reflects differences in disease biology between the 2 populations or simply reflects the higher number of resections done for advanced stage disease in Japan is unclear.

The improved results for gallbladder cancer reported with extended procedures coupled with an appreciation that radical surgical resection for hilar cholangiocarcinomas20–22 improves survival (unpublished data from our institution) led to a reappraisal of our technical approach to gallbladder cancer in the mid-1990s. Since then, we have adopted a more aggressive strategy that consists of liver resection and complete excision of the extrahepatic/pancreatic biliary tree with lymphadenectomy to achieve an R0 resection. To evaluate the effects of this shift in management, we have divided this cohort of 99 consecutive patients into 2 groups, comparing the first 6 years to those in the last 6 years (seventh through 12th years) of the review.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A retrospective study spanning a 12-year period from January 1990 to May 2002 was performed, and a total of 99 consecutive inpatients were identified. Cases were divided into 2 time-period cohorts, those treated in the first 6 years (TP1, N = 35) and those treated in the last 6 years (TP2, N = 64). Approval for chart review was obtained from the institutional review boards at both the Toronto General and Mount Sinai Hospitals of the University of Toronto. All inpatient admissions with the diagnosis of gallbladder cancer were included, and each patient's inpatient hospital and clinic chart was reviewed. Surgical mortality was considered as death occurring within 30 days of surgery. Morbidity included minor complications requiring no intervention, while major complications required intervention.

Preoperative assessment included history, physical examination, and radiographic studies: magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). In TP1, patients were staged with transabdominal ultrasound and double-contrast (IV and oral) computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest/abdomen/pelvis; jaundiced patients underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Patients in TP2 underwent a transabdominal ultrasound, CT scan of the chest/abdomen/pelvis, and usually triphasic CT scan of the liver; jaundiced patients underwent either ERCP or MRCP. Staging laparoscopy was performed infrequently in selected patients in TP2; 3 patients were incidentally found to have gallbladder cancer prior to referral and underwent staging laparoscopy at our institution. In one of these patients, peritoneal metastases were found. Major hepatic resections were performed using standard techniques.6 Previous laparoscopic port sites were resected if present. In the early years of the study, parenchymal transection was performed using a crush clamp technique. Later, parenchymal division was accomplished using an ultrasonic dissector and more recently (since March 2002), a precision water dissection system (Hydro-Jet, ERBE, Teubingen, Germany) has been used. Central venous pressure was maintained at 5 cm H2O or less during the parenchymal transection phase. Complete inflow occlusion was rarely used. Excision of the extrahepatic biliary tree included the gallbladder, the biliary confluence down to its cephalad junction with the pancreas in continuity, with a complete portal lymphadenectomy to the suprapyloric lymph node23 overlying the hepatic artery–gastroduodenal artery junction, skeletonizing the portal vein and hepatic artery. Biliary reconstruction, to a Roux-en-Y loop of jejunum, was performed using a single layer of 5–0 PDS interrupted sutures.

Definitions

Terminology with respect to liver resections is that proposed by the International Hepato-Pancreatico-Biliary Association (IHPBA), also known as the Brisbane terminology (Terminology Committee of the IHPBA, www.ihpba.org/html/guidelines/index.html). Resections may also be described by the Couinaud segments resected.24–26 Wedge resection denotes a nonanatomic, nonsegmental resection of the liver surrounding the gallbladder to a depth of 1 to 2 cm. We have elected to use the staging system proposed by Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.7 In contradistinction to the TNM (AJCC) staging system, the Memorial system categorizes T4N0M0 lesions as stage IIIb as opposed to stage IV (TNM).

Statistics

Univariate comparisons were made with the Fisher exact test or χ2 test for dichotomous covariates, and the t test for continuous variables. Patients were divided into 2 groups, depending on the time in which they received treatment (TP1 = 1990–1996, TP2 = 1997–2002). Numerical data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise indicated. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05. Patient survival was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Comparisons of patient survival curves were made using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression modeling was used to assess the effect that independent covariates had on the dependent variable survival. Logistic regression modeling was performed to assess the impact of the covariates on the presence or absence of complications. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Demographics

Ninety-nine patients admitted with gallbladder cancer from 1990 to 2002 were identified. Thirty-three patients were male and 66 female, with an average age at presentation of 64 years (37–88).

Presenting Symptoms/Signs

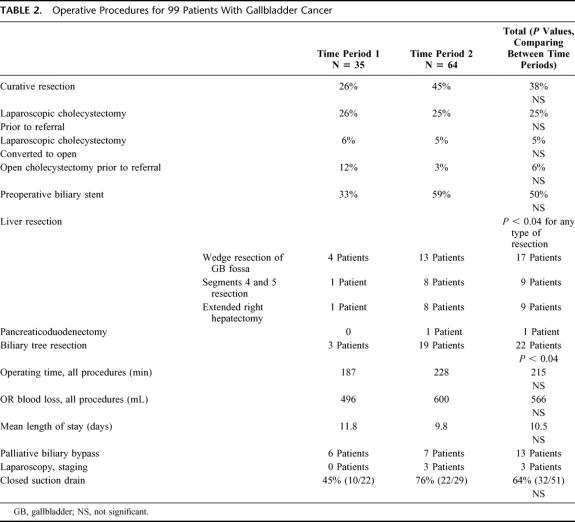

(Table 1) The most common presenting symptom was pain in 76% of patients, and this was the only symptom that was significantly different between time periods (83% TP1 versus 62% TP2, P < 0.03). Forty-five percent presented with obstructive jaundice. Overall, 22% presented with a palpable mass, and weight loss (average of 18 pounds) occurred in 32% of patients. The most common provisional diagnosis prior to intervention was gallbladder cancer (38%); 62% of patients had the wrong diagnosis prior to intervention. These included biliary colic (24%), acute cholecystitis (12%), cholangiocarcinoma (12%), cholangitis/choledocholithiasis/gallstone pancreatitis (5%), gallbladder polyp (4%), miscellaneous (3%), and chronic cholecystitis (1%).

TABLE 1. Characteristics of 99 Patients With Gallbladder Cancer

Interventions Prior to Definitive Therapy

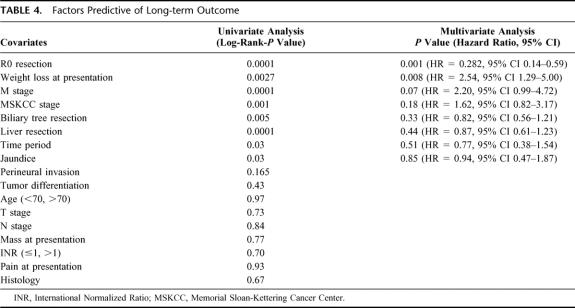

Twenty-five percent of patients underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy prior to referral to our center. One fifth of these were converted to an open procedure. An additional 6% of patients underwent an open cholecystectomy prior to referral. Of the 51 patients who were explored with curative intent at our institution, 50% had a biliary stent (endobiliary or transhepatic) placed prior to surgery to relieve jaundice.

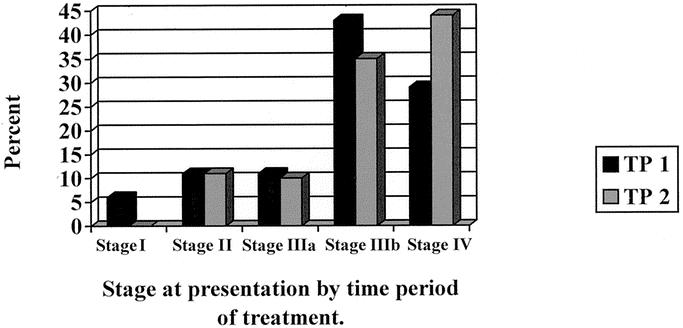

Disease Stage

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of patients by stage, as well as by time period. The majority of patients (73%) presented with advanced disease (stage IIIb or IV). There was a trend towards presentation with higher stage disease in patients during TP2 (79% Stage IIIB or IV) that did not reach statistical significance (P < 0.26).

FIGURE 1. Stage of disease at presentation by time period of treatment.

Definitive Therapy

Table 2 shows the operative features of the entire cohort. Of the 99 patients treated, 51 patients were explored for a potentially curative resection at our institution; 38 underwent an R0 resection (R0 resection, microscopic and macroscopic negative margins), and 13 had a palliative procedure or diagnostic biopsy. A further 10 patients had a palliative operation (bypass procedure) for gastrointestinal obstruction. The remaining 38 patients had advanced disease and did not undergo any surgery. Nine patients in TP1 and 29 in TP2 had R0 resections. Thirty-five patients underwent a concomitant liver resection (6 in TP1 versus 29 in TP2, P < 0.04). The majority in TP1 underwent a nonanatomic wedge resection of the liver surrounding the gallbladder. However, in TP2, 13 patients had a limited liver resection (wedge resection), 8 had an anatomic resection of segments 4b and 5, and an extended right hepatectomy was performed in 8 cases. Complete resection of the extrahepatic/extrapancreatic biliary tree was performed in 3 patients in TP1 and 19 in TP2. Of patients undergoing R0 resections involving a concomitant liver resection, 4 of 6 were stage IIIb or IV in TP1, while 23 of 28 had stage III disease or higher in TP2. One patient had a concurrent en-bloc pancreaticoduodenectomy for a positive biliary resection margin on frozen section at the cephalad border of the pancreas. Average overall operating time was 215 minutes. Estimated average blood loss for both groups was 566 mL.

TABLE 2. Operative Procedures for 99 Patients With Gallbladder Cancer

In total, 17 patients received chemotherapy (14 palliative, 3 adjuvant), and 5 patients received radiotherapy (all palliative). The frequency of use of chemotherapy and radiotherapy did not differ significantly between time periods.

Perioperative Complications

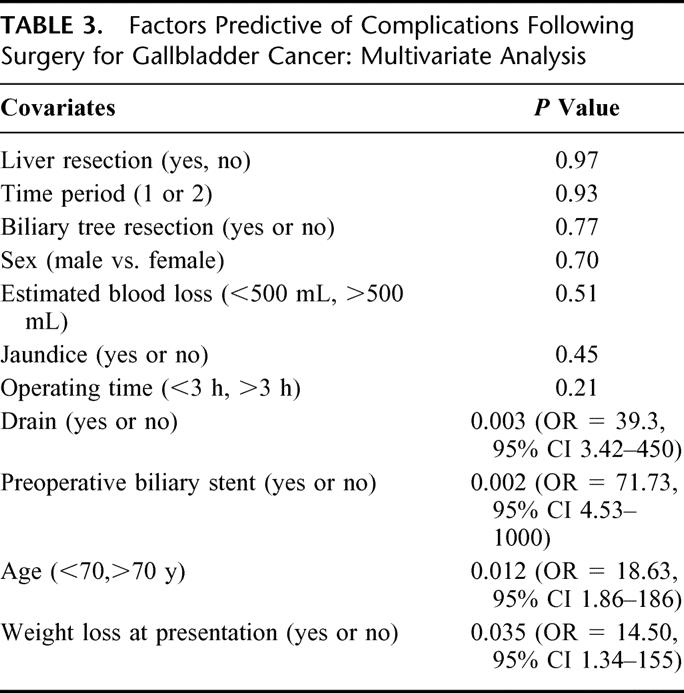

Operative mortality was 2% (1/51). The death occurred as a result of liver failure following an extended right hepatectomy and biliary tree resection in a patient with unsuspected alcoholic liver disease. The morbidity rate for all patients was 49%. Complications included cholangitis (16%), wound infection (10%), liver failure (4%), pneumonia (4%), intraabdominal abscess (4%), delirium (2%), postoperative bowel obstruction (2%), bile leak (2%), DVT/pulmonary embolus (2%), upper GI bleed (2%), and renal failure (2%). Two patients required reoperation; 1 was for a persistent bile leak. The second was for a bowel obstruction following a palliative biliary and gastric bypass as a result of unrecognized tumor involvement of the right colon. Two other patients developed intraabdominal abscesses requiring percutaneous drainage. Mean length of stay was 10.5 days. Multivariable analysis revealed that preoperative biliary stent placement, intraoperative drain placement, advanced age (>70 years), and weight loss at presentation were associated with the development of complications (Table 3). Although multiple factors likely contributed to the development of complications, it appeared that closed suction drains may have resulted in wound infections and bile leaks and that preoperative biliary stents may have increased the risks of both wound infections and cholangitis. Drains may increase the risk of biliary leak if placed in close proximity to a divided biliary radicle. Similarly, if the drain exits the skin in close proximity to the wound, this may contribute to postoperative wound infection.

TABLE 3. Factors Predictive of Complications Following Surgery for Gallbladder Cancer: Multivariate Analysis

Pathology

The distribution of histologies included adenocarcinoma (88%), mucinous variant (4%), papillary (3%), adenosquamous (2%), and squamous (2%). Tumor differentiation was classified as moderately differentiated (53%), poorly differentiated (27%), and well differentiated (20%). Of note, 17% of tumors exhibited perineural invasion. Twenty cases had involved regional lymph nodes.

Survival Analysis

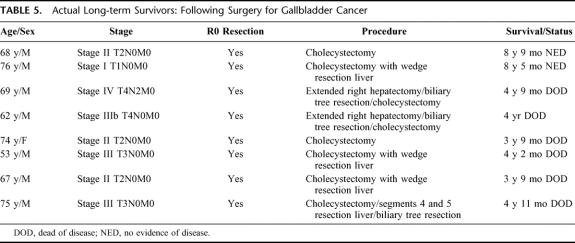

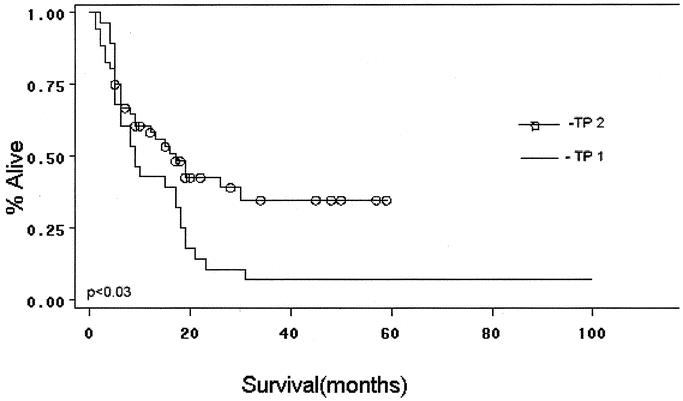

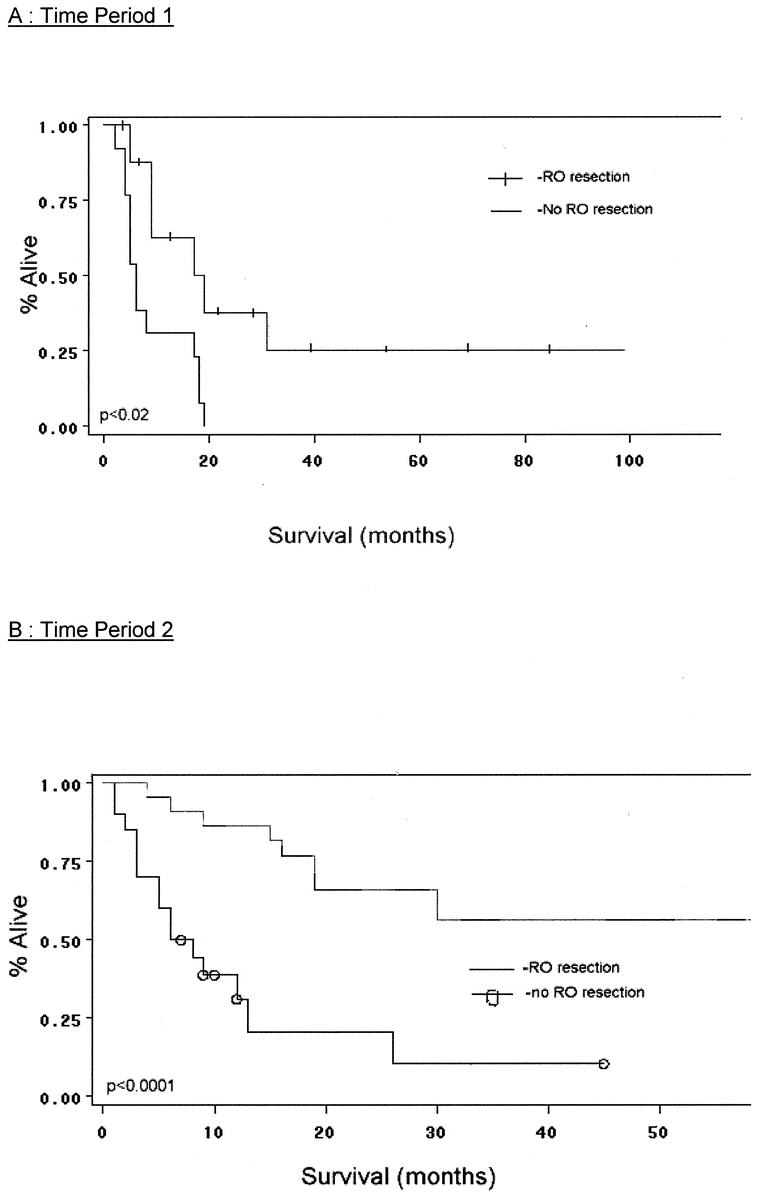

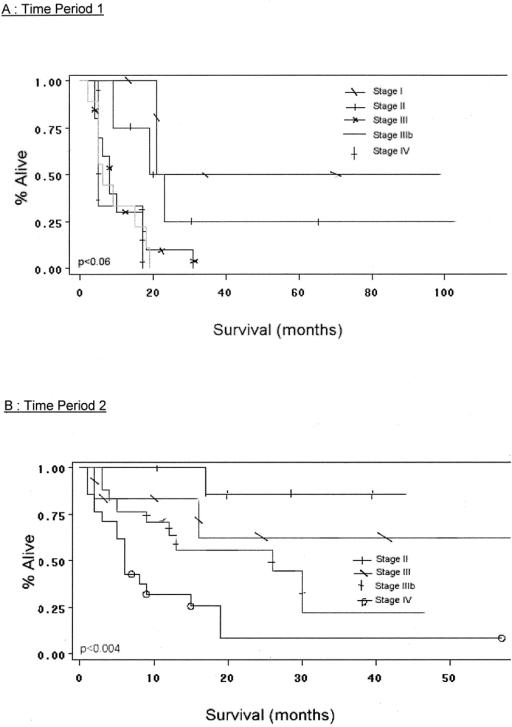

Survival analysis and comparisons between time periods are shown in Figures 2 3, and 4. As a group, TP2 patients had improved overall survival compared with cases treated in TP1 (Fig. 2). Five-year survival in TP1 and 2 is 7%, and 35%, respectively. Median survival in TP1 was 9 months, while in TP2 it was 17 months. Patients in both time periods had improved survival with complete (R0) surgical removal of all malignant disease (P < 0.02 TP1; P < 0.0001 TP2 (Fig. 3A, B). Median survival in TP1 for those undergoing an R0 resection versus those not having an R0 resection was 18 months and 6 months, respectively (P < 0.02). Similarly, in TP2, median survival was 19 months versus 7 months for R0-negative cases (P < 0.0001). Analysis of survival by stage in each time period reveals that patients in TP2 had improved survival, even when controlling for stage. Furthermore, differences in survival by stage in each time period are significant (P value TP1 < 0.04, TP2 < 0.0013; Fig. 4A, B). A multivariate analysis of factors found to have significance upon univariate analysis revealed that only those patients undergoing an R0 resection, and with an absence of weight loss at presentation, manifest a statistically significant improvement in overall survival (Table 4).

FIGURE 2. Overall survival by time period: Kaplan-Meier curve.

FIGURE 3. A, Effect of R0 resection on survival (time period 1). B, Effect of R0 resection on survival (time period 2).

FIGURE 4. A, Survival by stage (time period 1). B, Survival by stage (time period 2).

TABLE 4. Factors Predictive of Long-term Outcome

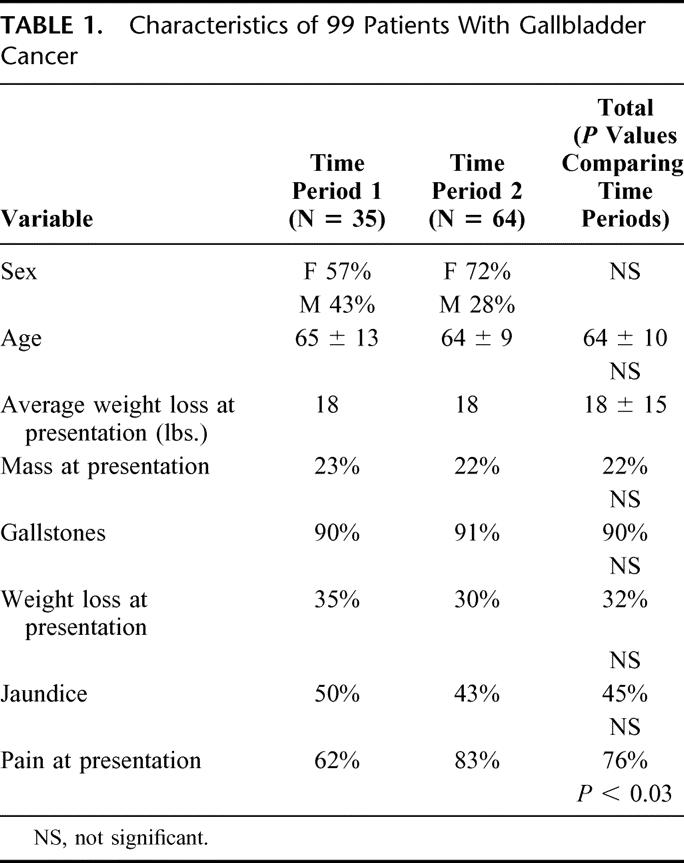

A description of the 8 long-term survivors is shown in Table 5. Eight patients suffered a local recurrence (mean time to recurrence, 12.3 months) and 18 relapsed with metastatic disease (mean time, 11.1 months; Fig. 4). One patient was found to have microscopic disease in the port site after resection; this patient had an extended hepatectomy and a concomitant pancreaticoduodenectomy. This patient was classified as having metastatic disease (stage IV) and recurred with local and distant metastases within a year. A total of 4 patients had port site recurrences, in 2 cases after resection of the port site.

TABLE 5. Actual Long-term Survivors: Following Surgery for Gallbladder Cancer

DISCUSSION

Five-year survival for carcinoma of the gallbladder in “Western” series ranges between 5% and 12%.2,3 These dismal results are related to the aggressive biology of this cancer and advanced disease due to late presentation. Recently, 5-year survival rates as high as 36% have been reported in patients undergoing “radical” resection in Japanese centers,19 which suggests that with optimal surgical management, locoregional recurrence may be reduced. Fong et al19 and Fong and Malhotra27 have reported similar results in North America with 38% 5-year survival in resected patients. These results, along with an appreciation that R0 resections improve outcome in patients with hilar biliary cancer,20–22 led to a reappraisal of our surgical approach to gallbladder cancer in the mid-1990s. In this report, we compare the operative management and survival outcomes of 2 distinct surgical approaches we have applied to this disease over the past 12 years.

Our results confirm that radical resections including the liver and/or biliary tree can be performed safely with minimal mortality (2%). However, complications are common, with major complications requiring intervention occurring in 29% of cases. Multivariate analysis demonstrated the most important factor determining long-term survival is the performance of a margin negative, R0 resection (P < 0.001). Although no R1 resections were intentionally performed in our study, prior investigators have demonstrated that R1, or debulking operations, do not improve survival.16,28,29

Our current management algorithm for patients with carcinoma of the gallbladder is described below. For patients who present with early-stage (T1) cancers following removal of the gallbladder elsewhere, we conduct a review of the pathology specimen, with attention to depth of invasion, margin status, lymphatic and perineural invasion, and anatomic location of the mass within the gallbladder. If these features confirm early-stage (T1N0M0) disease, cholecystectomy alone is adequate treatment of these cases, with close follow-up to detect local recurrence. However, if there is any concern that the lesion is T2, ie, has penetrated the full thickness of the muscularis into the subserosal plane (perimuscular plane on liver side of gallbladder, generally the plane of dissection used in simple cholecystectomy), then an extended cholecystectomy including liver ± bile duct resection is performed; in this not-infrequent scenario where exploration is performed after prior gallbladder removal, it is exceedingly difficult to differentiate scar from cancer, as has been previously appreciated.27 Furthermore, port sites are excised if the patient has undergone a laparoscopic cholecystectomy as the initial intervention.

Similarly, lesions that are initially staged as T2 or T3 are treated with a liver resection, either a segment 4b/5 resection, right hemihepatectomy or an extended right hepatectomy. The decision regarding the type of liver resection is based somewhat on the anatomic location of the tumor. Lesions located predominantly in the fundus can be treated with a segment 4b/5 resection. Those located in Hartmann pouch, the gallbladder neck, or extending into the triangle of Calot (ie, those close to the hilar plate and biliary confluence) require an extended liver resection to ensure negative margins. This requires resection of the extrahepatic/extrapancreatic biliary tree, including the horizontal course of the left hepatic duct over to the umbilical fissure. In these cases, an extended right hepatectomy is generally performed with reconstruction to the left hepatic duct at the base of the umbilical fissure. All T4 lesions are likewise treated with extended hepatectomy.

In the circumstance where the patient presents prior to any surgical intervention with T2 or worse gallbladder cancer, we perform a liver resection. Our approach to the biliary tree is individualized. If patients present with obstructive jaundice, the biliary tree is resected. If the lesion is located predominantly in Hartmann pouch, the neck of the gallbladder, or appears to extend down the cystic duct, then a biliary tree resection is performed. We perform a complete portal lymph node dissection, with thorough skeletonization of the portal structures, down to and including the suprapyloric lymph node overlying the hepatic–gastroduodenal artery junction. We agree with Fong and Malhotra27 with regard to treatment of bulky disease along the hepatoduodenal ligament, and in these circumstances we resect the biliary tree to facilitate a complete nodal dissection. Segment 4b/5 resections are limited to those patients with T3 or lower fundal lesions and in those patients in which there is clearly a negative margin towards the right pedicle/plate. Extended hepatectomy is performed in all patients with T4 lesions or any lesion in which a negative or close margin is a concern. Generally, this entails an extended right hepatectomy; however, in rare cases where the bulk of the tumor encroaches on the umbilical fissure, or intrabiliary extension of tumor is predominantly along the left duct, then an extended left hepatectomy is performed. All jaundiced patients, patients with bulky nodal disease along the hepatoduodenal ligament, and any other patient with a positive cystic duct margin undergo a biliary resection. Other contiguous organ involvement is resected en bloc.

The main limitation of this study is its retrospective, nonrandomized nature. By comparing outcomes in the seventh through 12th years to those in the first 6 years, we are using historical controls as a reference point for the new surgical approach. The main drawback to this type of comparison is that it is possible that the overall management of these patients has changed over time, irrespective of surgical factors. Some of these changes include improved diagnostic imaging and staging, variability in referral patterns, better patient selection, and improved perioperative care. To gauge the impact of known possible confounders, we performed a multivariate analysis. However, this does not take into account unknown confounders, but it is unlikely that any unknown confounder could account for the magnitude of difference in survival between time periods. By including in the multivariate analysis the time period in which therapy occurred, unknown confounders related to the time period are accounted for indirectly. A randomized trial comparing extended versus limited surgical resection would be the ideal manner to test this concept, but this cannot be performed because of the paucity of cases, as well as the lack of therapeutic equipoise, given the current evidence in our study and others.8–19,27,29–36 Adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapies were not used to any great extent in either time period, making them unlikely to account for the differences in outcomes.

In summary, a marked improvement in outcome of patients with gallbladder cancer has been achieved over the past 6 years, primarily due to a shift towards more aggressive surgery. Multivariate examination accounting for the time period in which treatment occurred reveals that the most important factor determining long-term survival is whether the patient underwent an R0 surgical resection. However, even in the most recent time period, a maximal 5-year survival rate of only 35% has been achieved; therefore, it is essential that novel adjuvant therapies be developed and evaluated for these patients.

Footnotes

Reprints: Steven Gallinger MD, MSc, FRCSC, Professor of Surgery, 600 University Avenue, Room 1225, Mount Sinai Hospital, Department of Surgery, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M5G 2C4. E-mail: steven.gallinger@uhn.on.ca.

REFERENCES

- 1.Piehler JM, Crichlow RW. Primary carcinoma of the gallbladder. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1978;147:929–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cubertafond P, Gainant A, Cucchiaro G. Surgical treatment of 724 carcinomas of the gallbladder: results of the French Surgical Association Survey. Ann Surg. 1994;219:275–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilkinson DS. Carcinoma of the gall-bladder: an experience and review of the literature. Aust N Z J Surg. 1995;65:724–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fong Y, Fortner J, Sun RL, et al. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 1999;230:309–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jarnagin WR, Gonen M, Fong Y, et al. Improvement in perioperative outcome after hepatic resection: analysis of 1803 consecutive cases over the past decade. Ann Surg. 2002;236:397–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor M, Forster J, Langer B, et al. A study of prognostic factors for hepatic resection for colorectal metastases. Am J Surg. 1997;173:467–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartlett DL, Fong Y, Fortner JG, et al. Long-term results after resection for gallbladder cancer: implications for staging and management. Ann Surg. 1996;224:639–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kondo S, Nimura Y, Hayakawa N, et al. Regional and para-aortic lymphadenectomy in radical surgery for advanced gallbladder carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2000;87:418–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kondo S, Nimura Y, Hayakawa N, et al. Extensive surgery for carcinoma of the gallbladder. Br J Surg. 2002;89:179–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kondo S, Nimura Y, Kamiya J, et al. Mode of tumor spread and surgical strategy in gallbladder carcinoma. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2002;387:222–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kondo S, Nimura Y, Kamiya J, et al. Five-year survivors after aggressive surgery for stage IV gallbladder cancer. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2001;8:511–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shirai Y, Ohtani T, Tsukada K, et al. Radical surgery is justified for locally advanced gallbladder carcinoma if complete resection is feasible. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:181–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shirai Y, Ohtani T, Tsukada K, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for gallbladder cancer with peripancreatic nodal metastases. Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44:376–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shirai Y, Ohtani T, Tsukada K, et al. Combined pancreaticoduodenectomy and hepatectomy for patients with locally advanced gallbladder carcinoma: long term results. Cancer. 1997;80:1904–1909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shirai Y, Yoshida K, Tsukada K, et al. Radical surgery for gallbladder carcinoma: long-term results. Ann Surg. 1992;216:565–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Todoroki T, Kawamoto T, Takahashi H, et al. Treatment of gallbladder cancer by radical resection. Br J Surg. 1999;86:622–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Todoroki T, Takahashi H, Koike N, et al. Outcomes of aggressive treatment of stage IV gallbladder cancer and predictors of survival. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:2114–2121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doty JR, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, et al. Cholecystectomy, liver resection, and pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy for gallbladder cancer: report of five cases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2002;6:776–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fong Y, Jarnagin W, Blumgart LH. Gallbladder cancer: comparison of patients presenting initially for definitive operation with those presenting after prior noncurative intervention. Ann Surg. 2000;232:557–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chamberlain RS, Blumgart LH. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a review and commentary. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langer JC, Langer B, Taylor BR, et al. Carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile ducts: results of an aggressive surgical approach. Surgery. 1985;98:752–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Launois B, Terblanche J, Lakehal M, et al. Proximal bile duct cancer: high resectability rate and 5-year survival. Ann Surg. 1999;230:266–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujii K, Isozaki H, Okajima K, et al. Clinical evaluation of lymph node metastasis in gastric cancer defined by the fifth edition of the TNM classification in comparison with the Japanese system. Br J Surg. 1999;86:685–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Couinaud C. [Surgical anatomy of the liver: several new aspects]. Chirurgie. 1986;112:337–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Couinaud C. [The anatomy of the liver]. Ann Ital Chir. 1992;63:693–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Couinaud C. [Intrahepatic anatomy: application to liver transplantation]. Ann Radiol (Paris). 1994;37:323–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fong Y, Malhotra S. Gallbladder cancer: recent advances and current guidelines for surgical therapy. Adv Surg. 2001;35:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shirai Y, Ohtani T, Tsukada K, et al. Predictors of survival in patients with carcinoma of the gallbladder. Cancer. 1997;79:185–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsukada K, Hatakeyama K, Kurosaki I, et al. Outcome of radical surgery for carcinoma of the gallbladder according to the TNM stage. Surgery. 1996;120:816–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fong Y, Brennan MF, Turnbull A, et al. Gallbladder cancer discovered during laparoscopic surgery: potential for iatrogenic tumor dissemination. Arch Surg. 1993;128:1054–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fong Y, Heffernan N, Blumgart LH. Gallbladder carcinoma discovered during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: aggressive reresection is beneficial. Cancer. 1998;83:423–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kondo S, Nimura Y, Hayakawa N, et al. [Rationale of paraaortic lymph nodes dissection for advanced gallbladder cancer]. Nippon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1990;91:223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kondo S, Nimura Y, Hayakawa N, et al. [Value of paraaortic lymphadenectomy for gallbladder carcinoma]. Nippon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1998;99:728–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shoup M, Fong Y. Surgical indications and extent of resection in gallbladder cancer. Surg Oncol Clin North Am. 2002;11:985–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsukada K, Yoshida K, Aono T, et al. Major hepatectomy and pancreatoduodenectomy for advanced carcinoma of the biliary tract. Br J Surg. 1994;81:108–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wakai T, Shirai Y, Hatakeyama K. Radical second resection provides survival benefit for patients with T2 gallbladder carcinoma first discovered after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J Surg. 2002;26:867–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]