Abstract

Objective:

To assess the effectiveness of different strategies for increasing the uptake of prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism (VTE) in hospitalized patients through a systematic review of the literature.

Methods:

Literature databases and the Internet were searched from 1996 to May 2003. Studies of strategies to improve VTE prophylaxis practice were included. Studies where no policy or guideline was implemented or where the focus of the study was not VTE prevention were excluded.

Results:

Thirty studies were included. The quality of the available evidence was average with the majority of studies being uncontrolled before and after design and thus limited by the historical nature of much of the available data. Adherence to guidelines and the provision of adequate prophylaxis were poor in studies which relied on passive dissemination of guidelines. In general, the use of multiple strategies was more effective than a single strategy used in isolation. The most effective strategies incorporated a system for reminding clinicians to assess patients for VTE risk, either electronic decision-support systems or paper-based reminders, and used audit and feedback to facilitate the iterative refinement of the intervention. There were no studies adequately powered to demonstrate a reduction in rates of VTE. Insufficient evidence was available to make useful comparisons of strategies in terms of costs and resource utilization.

Conclusions:

Passive dissemination of guidelines is unlikely to improve VTE prophylaxis practice. A number of active strategies used together, which incorporate some method for reminding clinicians to assess patients for DVT risk and assisting the selection of appropriate prophylaxis, are likely to result in the achievement of optimal outcomes.

This paper reviewed strategies for improving the uptake of prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in hospitalized medical and surgical patients. A number of active strategies used together, incorporating a method for reminding clinicians to assess patients for risk of deep vein thrombosis, and assisting the selection of appropriate prophylaxis, are likely to result in the best outcomes.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a significant problem for surgical and medical hospitalized patients, leading to the possibility of serious illness and risk of death. A number of clear evidence-based guidelines are available which outline the appropriate use of prophylaxis to prevent deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).1–10 In spite of the existence of such evidence, the problem of VTE in hospitalized patients persists, and it is clear that evidence-based guidelines and recommendations are underutilized. The challenge of translating evidence into practice is a widespread problem across a range of healthcare settings and clinical problems. It is clear that there is no “one-size-fits-all” solution which will be effective for every setting and every health problem. A systematic review was undertaken which aimed to evaluate strategies used to increase the uptake of VTE prophylaxis for hospitalized patients and to make recommendations about the effectiveness of different strategies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Inclusion Criteria

Studies of all types regarding prophylaxis for DVT or PE were included (randomized controlled trials (RCTs), historical and/or nonrandomized comparative studies, case series, case reports, surveys, and clinical audit reports). All studies were retrieved without language restriction and subsequently excluded if they did not add substantially to the English language evidence base. Studies were excluded if there was no evidence regarding the success of DVT policy implementation (ie, at least postimplementation outcomes) or where no results, either quantitative or qualitative, could be extracted from the study. The included papers contained information on at least 1 of the following outcomes: outcomes of care (such as rates of DVT), processes of care (such as adequacy of prophylaxis), processes of change (such as adherence to guidelines), and resource utilization and costs. Two reviewers independently examined all retrieved references, and any disagreement over inclusion or exclusion was discussed and a consensus reached.

Search Strategy

Ovid PreMEDLINE and MEDLINE, Current Contents, Cochrane Library's Controlled Trials Register and Database of Systematic Reviews, DARE and NHS-EED, and EMBASE from 1996 up to and including May 2003 were all searched. The UK National Research Register (NRR), NIH ClinicalTrials.Gov database, PubMed, and HTA Assessment database were also searched in May 2003. Gray literature was also extensively searched from 1996 up to May 2003. Pearling was then undertaken to locate articles that may have been missed by the electronic database searches.

Specific search terms to retrieve articles were venous thromboembolism (VTE), deep vein (venous) thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), prophylaxis, prevention guidelines, protocol, policy, implementation, clinical practice, hospital, postoperative in PreMEDLINE, MEDLINE, Current Contents, EMBASE, and PubMed. In other databases (Cochrane Library, NHS HTA databases, Clinical Trials database, NRR, SIGLE), the search terms used were venous thromboembolism (VTE), deep vein (venous) thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE).

Data Extraction and Analysis

Data were extracted from each included study using standardized study profile tables developed a priori. Each included study was critically appraised for its study quality and “level of evidence” according to the hierarchy of evidence developed by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.11 Study quality was assessed on a number of parameters such as the quality of the study methodology reporting, methods of randomization and allocation concealment (for RCTs), blinding of patients or outcomes assessors, attempts made to minimize bias, sample sizes, and the ability of the study to measure “true effect.” The applicability of results outside the study sample was also examined, as were the appropriateness of the statistical methods used to describe and evaluate the study data.

RESULTS

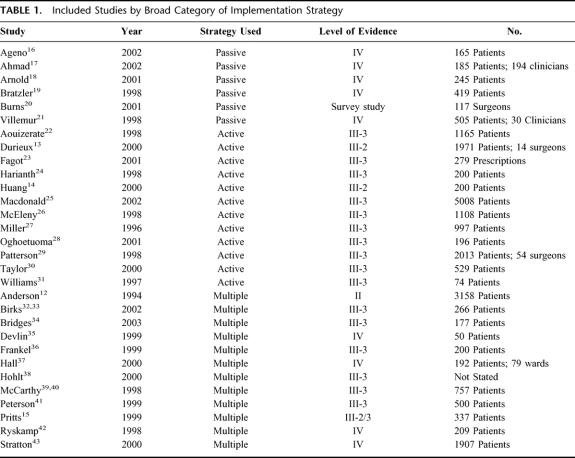

Thirty studies were identified which met the inclusion criteria (Table 1). Only 1 RCT comparing different strategies to increase VTE prophylaxis uptake could be identified.12 The majority of studies reported the results of an audit cycle prior to, and following, the implementation of VTE practice guidelines or a local protocol. Three of these studies were concurrently controlled,13–15 with the remainder being historically controlled or case series (see Table 1). The available data were weakened by their historical nature, with the possibility of bias introduced by differences in data collection or recording methods, changes in other hospital procedures over time, as well as changes in personnel or management structures. The majority of studies were not adequately powered to detect changes in rare patient outcomes such as rates of DVT or PE. There was also the strong possibility that much of the data was subject to the Hawthorne effect, such that behavior may have changed within the study setting as a result of the research process itself; for example, as a result of focusing on VTE prevention. As this may be seen as a positive outcome from a clinical perspective, there is little incentive for clinical researchers to seek to minimize this effect. As a result of the nature of the available data, conclusions were more easily made with regard to changing clinician behavior than with regard to influencing patient outcomes.

TABLE 1. Included Studies by Broad Category of Implementation Strategy

Strategies Used in the Included Studies

Strategies for increasing the uptake of VTE prophylaxis included passive dissemination, audit and feedback, computer-based decision aids, documentation aids, continuing education, quality assurance activities, advertising, appointment of specific implementation staff, and recruitment of local change agents or opinion leaders.

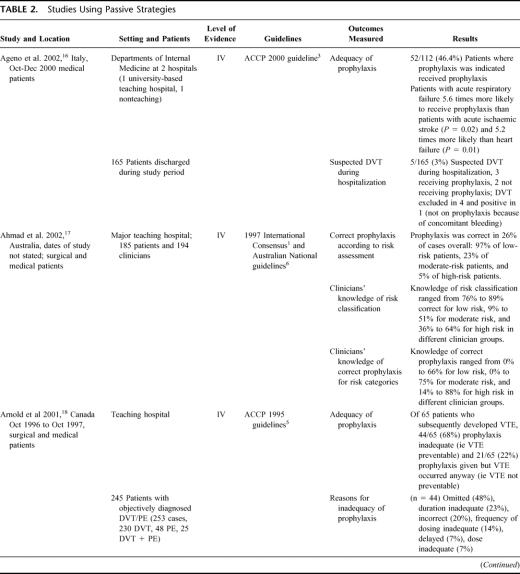

Studies Using Passive Dissemination

Six studies were identified which relied on the passive dissemination of guidelines (via international or local publication) to change VTE prophylaxis practice (see Table 2). 16–21 Adherence to guidelines and the provision of adequate prophylaxis was poor in these studies, with no more than 50% of patients receiving appropriate prophylaxis, despite dissemination of the guideline. These 6 studies underline the problem of uptake of VTE prophylaxis practices and suggest that the dissemination of evidence-based guidelines alone will not be enough to ensure that the majority of patients in need of prophylaxis receive it, nor that the prophylaxis provided is appropriate for the patient. It seems likely that a lack of knowledge regarding risk classification for VTE and appropriate treatment may be contributing to the poor practices documented in these 6 studies.

TABLE 2. Studies Using Passive Strategies

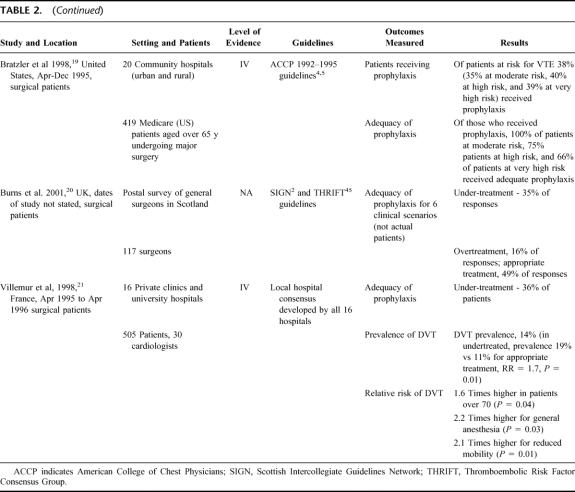

TABLE 2. (Continued)

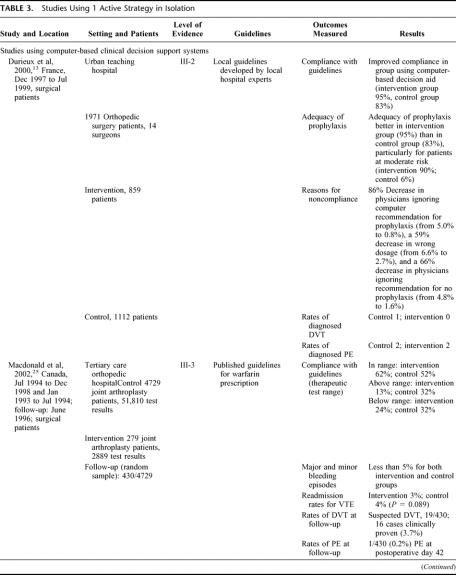

Studies Using a Single Active Strategy

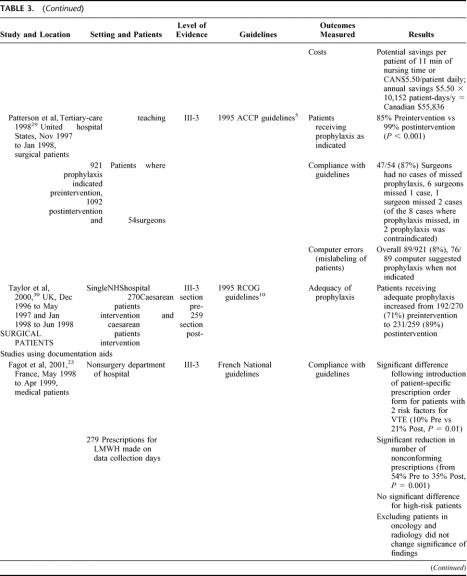

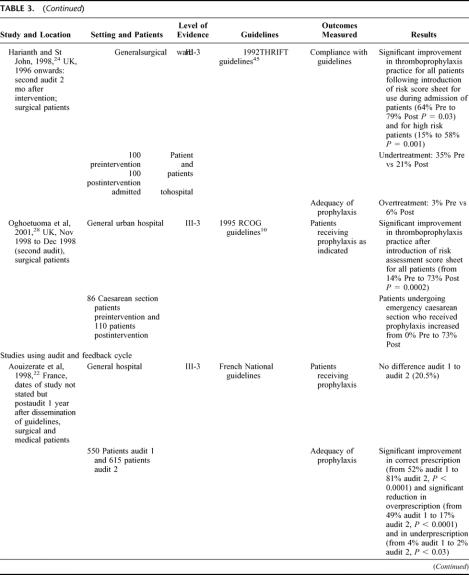

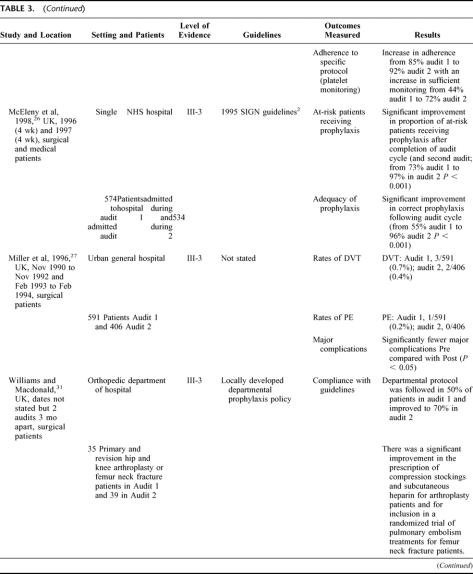

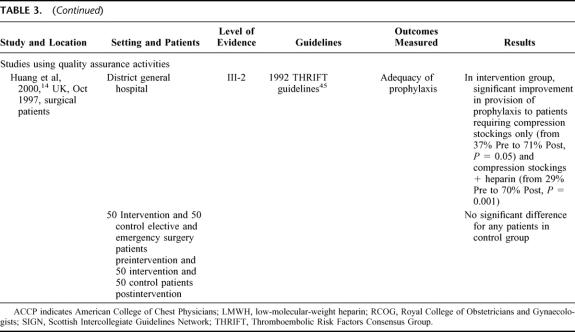

Twelve studies used 1 of 4 active strategies in isolation to improve VTE prophylaxis (see Table 3). 13,14,22–31 The 4 strategies used were computer-based clinical decision support systems, audit and feedback, documentary aids, and quality-assurance activities (in this case, active monitoring of VTE prophylaxis policy). While all of the strategies resulted in improvements in VTE prophylaxis practice, the most effective strategy for increasing adherence to guidelines and adequacy of prophylaxis appeared to be the computer-based clinical decision-support systems, with rates for each of these outcomes approaching 100%.13,25,29,30 In comparison, the other 3 strategies generally resulted in rates of around 80% for adherence to guidelines and adequacy of prophylaxis.14,22–24,27,28,31 However, in one study using audit and feedback, an iterative process was used to modify existing guidelines based on the results of the audit, and this produced outcomes similar to those obtained by the studies using computer-based decision aids.26

TABLE 3. Studies Using 1 Active Strategy in Isolation

TABLE 3. (Continued)

TABLE 3. (Continued)

TABLE 3. (Continued)

TABLE 3. (Continued)

This variability in outcomes may be attributed to 2 factors. The outcomes achieved by using the computer-based decision systems are likely to have resulted from the use of automatic reminders to assess VTE risk or assist in correct prescription of prophylaxis, which removed the element of human error from VTE prophylaxis practice. By comparison, in the 3 studies which used paper-based documentation aids, the reminder process was not automated, and thus the element of human error may still have affected the use of the various documentary aids. The effectiveness of the audit strategy used by McEleny et al26 appears to have hinged on the iterative process used to modify existing guidelines, and the possibility that in some departments/hospitals within the health system studied, VTE prophylaxis was already a priority area (as evidenced by the existence of local protocols).

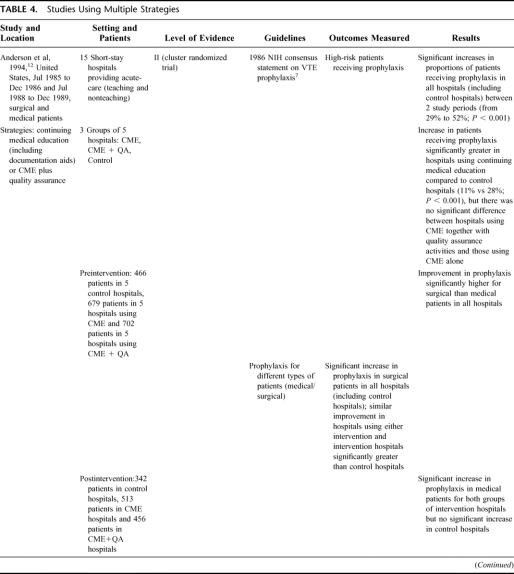

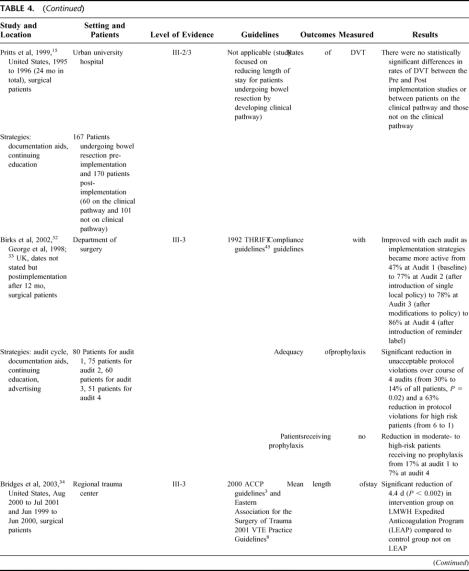

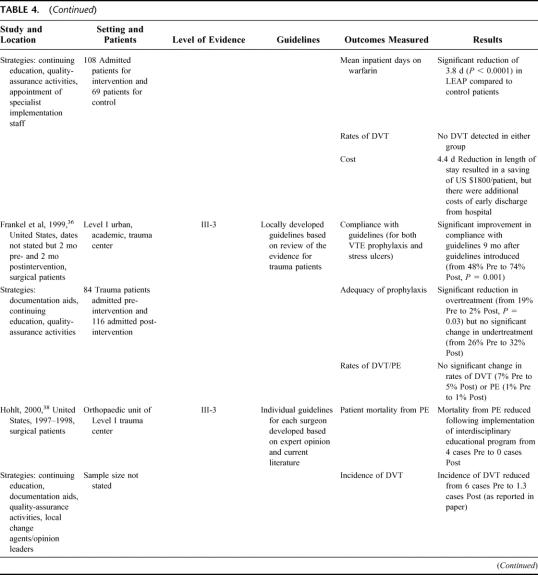

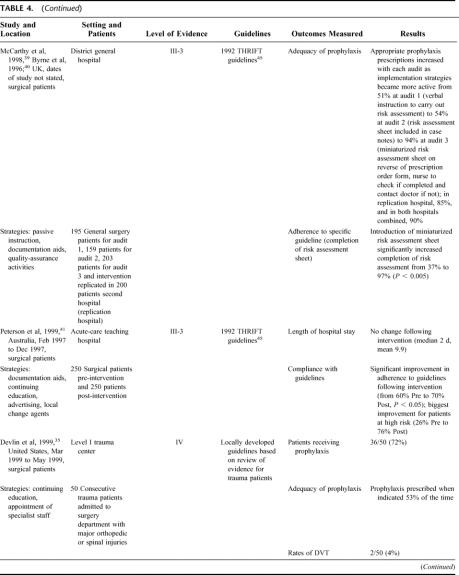

Studies Using Multiple Strategies

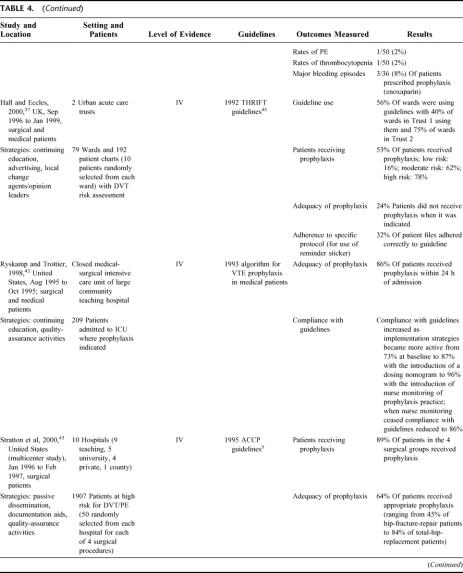

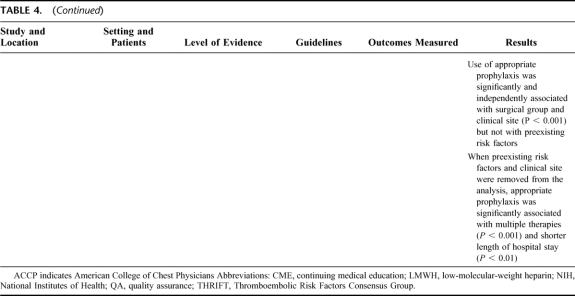

Twelve studies used multiple strategies to increase uptake of VTE prophylaxis (see Table 4). 12,15,32–43 Adherence to guidelines and adequacy of prophylaxis improved in all the studies where it was reported.12,32,33,36,39–41 The majority of studies used 3 strategies in combination, and all but 2 studies39,40,43 used continuing education. However, the studies with the best outcomes also used audit and feedback to facilitate iterative refinement of either prophylaxis policy or implementation strategy and/or used a documentary aid such as a paper-based reminder system to ensure that practitioners assessed patients for VTE risk and prescribed the appropriate prophylaxis. For example, in the Birks et al32,33 study, compliance with guidelines increased significantly with successive refinements in implementation strategy. Compliance with guidelines was initially 47% and reached 86% only when the strategy included not simply continuing education but also the introduction of a reminder label. McCarthy et al39 and Byrne et al40 demonstrated a similar progression in adequacy of prophylaxis, with successive increases occurring as the use of a documentation aid was refined to make it easier to access and finally when compliance with its use was actively monitored by a nurse. Adequacy of prophylaxis in this case increased from 51% with only verbal instruction to 94% after the final modification to the strategy.

TABLE 4. Studies Using Multiple Strategies

TABLE 4. (Continued)

TABLE 4. (Continued)

TABLE 4. (Continued)

TABLE 4. (Continued)

TABLE 4. (Continued)

Surgical Versus Medical Patients

Only 3 studies focused on the use of thromboprophylaxis in medical rather than surgical patients or reported results for medical patients separately from surgical patients.12,16,23 Anderson et al12 (Level II) found that the improvement in prophylaxis practice was significantly better for surgical than for medical patients, regardless of which intervention was used to increase use of prophylaxis. However, in the 2 groups of hospitals using active implementation strategies, there was a significant improvement in prophylaxis practice for medical patients compared with patients in the control hospitals. There was no clear advantage of continuing medical education plus quality-assurance activities compared with continuing education alone. Ageno et al16 documented relatively poor prophylaxis practice for medical patients in 2 Italian hospitals where passive dissemination of guidelines had occurred, with only 46% of patients receiving appropriate prophylaxis. Ageno et al16 noted a difference in practice, depending on the presenting condition, with patients with acute respiratory failure nearly twice as likely to receive prophylaxis as patients with acute ischemic stroke or heart failure. Fagot et al23 demonstrated that the provision of a patient-specific prescription order form improved compliance with French national guidelines for VTE prophylaxis and improved the accuracy of prescription in patients at moderate risk of VTE. However, no significant difference was found for patients at high risk.

Patient Outcomes and Resource Utilization

No studies were able to demonstrate a reduction in rates of DVT or PE as a result of the interventions to increase VTE prophylaxis, primarily due to a lack of power to detect these events. In 2 studies,25,34 length of hospital stay was reduced, leading to a cost saving in treating these patients. However, insufficient evidence was available to make useful comparisons of strategies in terms of costs and resource utilization.

DISCUSSION

Study Limitations

The conclusions which can be drawn from this review of literature regarding the uptake of VTE prophylaxis are limited by the nature of the available data. Only 1 RCT comparing different strategies to increase VTE prophylaxis uptake could be identified from the literature published within the last 10 years. The majority of studies report the results of an audit cycle where current practice is documented, a new policy or program to improve practice is implemented, and then practice is reaudited following this. To the extent that such studies concentrate on process of change outcomes, such as compliance with guidelines, or process of care outcomes, such as adequacy of prophylaxis, the retrospective comparative study design provides reasonable information regarding changes in prophylaxis practice. However, since much of the data is obtained from chart review, it is impossible to control for differences in data collection or recording methods, changes in other hospital procedures over time, as well as changes in personnel or management structures. Furthermore, the majority of studies do not contain a sufficient number of participants to obtain adequate statistical power to detect changes in rare patient outcomes such as rates of DVT or PE. There is also the strong possibility that much of the data is subject to the Hawthorne effect. This may be seen as a positive outcome from a clinical perspective, and thus there may be little incentive for clinical researchers to seek to minimize this effect. As a result of the nature of the available data, conclusions are more easily made with regard to changing clinician behavior than with regard to influencing patient outcomes.

Effectiveness of Various Strategies to Increase Uptake of VTE Prophylaxis

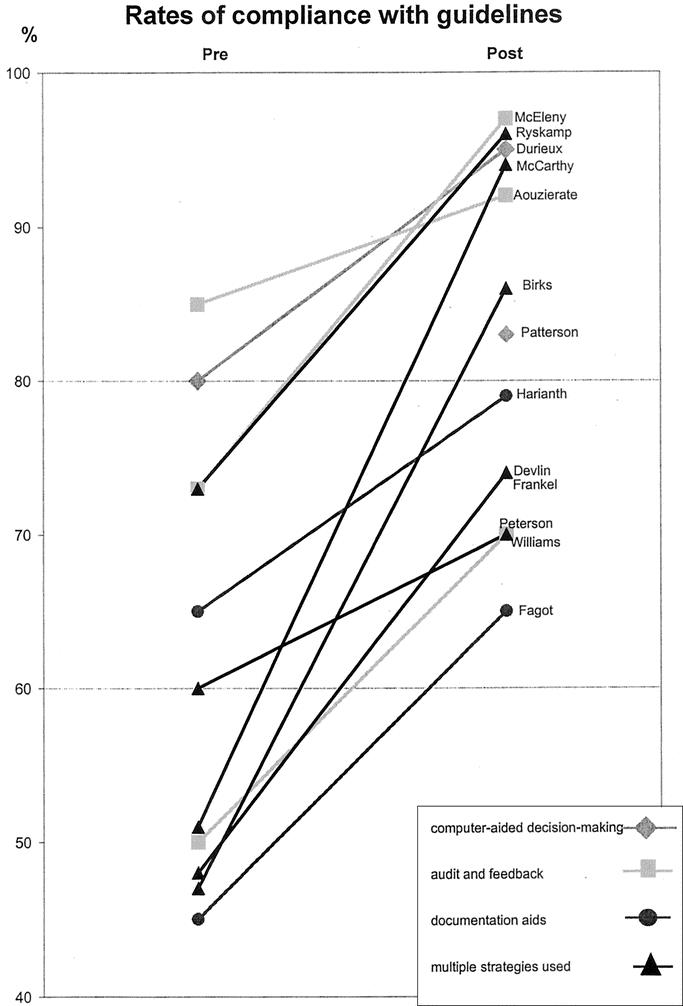

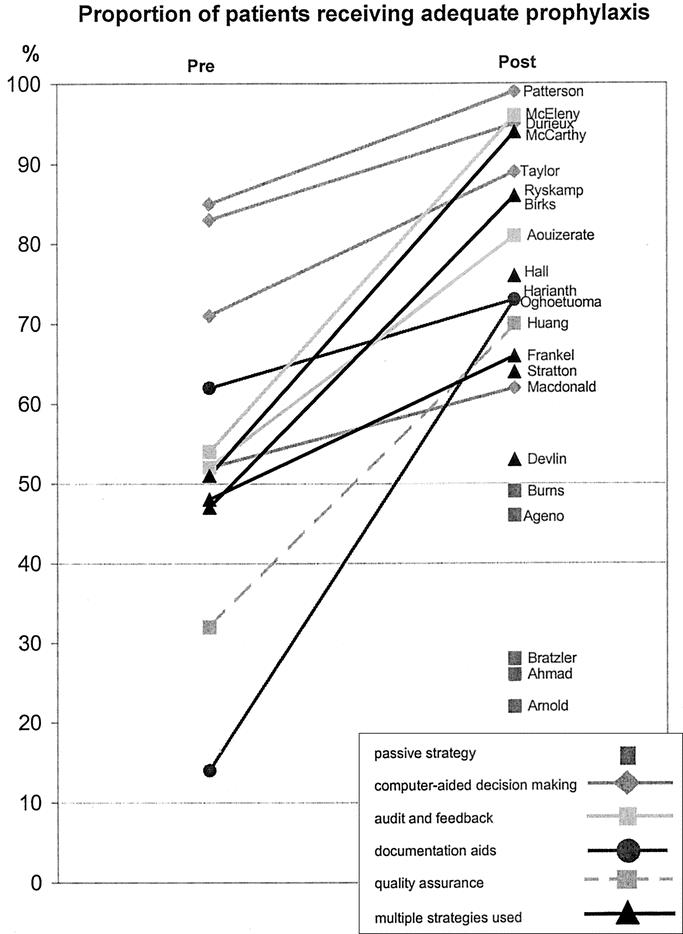

The evidence identified for this review included only 1 study which made a direct comparison between different strategies.12 In that study, adding quality-assurance activities to a continuing medical education program did not significantly improve prophylaxis practice compared with using the continuing education strategy alone. The majority of available evidence consists of indirect comparisons of postintervention rates of compliance with guidelines or adequacy of prophylaxis practice for studies using different implementation strategies. To facilitate such comparisons, Figures 1 and 2 graph each of the studies which reported these 2 outcomes. The slope of the line connecting the pre- and postintervention scores for each study provides an indication of how large an improvement was achieved, with steeper lines indicating a greater improvement than flatter lines. It should be kept in mind that these rates may be dependent on factors in each study setting which are not directly related to the strategy used for implementation, so that any comparison between studies must be made with caution.

FIGURE 1. Rates of compliance with guidelines pre- and postimplementation of prophylaxis strategy. The slope of the line indicates the extent of improvement with steeper lines indicating greater improvement.

FIGURE 2. Proportion of patients receiving adequate prophylaxis pre- and postimplementation of prophylaxis strategy. The slope of the line indicates the extent of improvement with steeper lines indicating greater improvement.

Nevertheless, some patterns are evident in Figures 1 and 2. In Figure 1, it can be seen that 5 studies achieved rates of adherence to guidelines above 90%.13,22,26,39,40,42 In terms of strategies used, these 5 studies are characterized by having either an iterative process of audit and feedback used to improve practice or refine implementation strategy22,26,39,40,42 or an active reminder process in place.13,39,40 On the other hand, of the 5 studies with the lowest rates of guideline adherence, only 1 used an audit and feedback strategy,31 and in this study no active iterative process was in place to improve practice after the audit. The other 4 studies relied primarily on continuing education to improve compliance with guidelines. The largest improvements in this outcome were also seen in the 3 studies using multiple strategies,32,33,39,40,42 which used successive audits to refine prophylaxis policy and implementation strategy.

In Figure 2, it is apparent that passive strategies for improving prophylaxis practice are not as effective as any of the active strategies. In general, it would appear that computer-based clinical-decision support systems are among the most effective strategies for improving prescribing practice, presumably because they minimize errors made by individual clinicians with varying degrees of interest, knowledge, and motivation for DVT and PE prevention. For this outcome, the highest scores were obtained in those studies which used either the computer-based decision support systems as discussed,13,29,30 or audit and feedback incorporating an iterative process.26,32,33,39,40,42 As with guideline compliance, lower scores were obtained in studies without an audit and feedback cycle,36,37,43 or where the documentation aid used did not provide an active reminder to assess VTE risk, or assistance to prescribe the appropriate prophylaxis.24,28 The quality-assurance strategy described by Huang et al14 resulted in adequate prophylaxis being provided to around 70% of patients, which was a significant improvement on rates in the control group. However, it seems likely that the single strategy of actively monitoring compliance is not sufficient for optimizing prophylaxis practice.

Are Multiple Strategies Better Than a Single Strategy?

In the studies included in this review, it was evident that for any intervention to significantly improve VTE prophylaxis practice, it needs to have at least 2 elements. First, it must help clinicians remember to assess the risk status of patients for VTE, and second, it must assist clinicians to prescribe the prophylaxis appropriate for the risk classification. Thus, it is unlikely that acceptable VTE prophylaxis practices will result from a reliance on passive dissemination of guidelines (either through international publication or local dissemination within a workplace). Rather, an active implementation process is required, and a number of active strategies used in combination are likely to be more effective than a single active strategy used in isolation. While improving clinician knowledge of VTE risk assessment and prophylaxis should help to improve practice, the evidence suggested that increased knowledge may not be particularly effective without the additional step of actively reminding clinicians to assess patients for VTE risk. Having reminded clinicians to assess patients for VTE risk and prescribe appropriate prophylaxis, a further effective step is then to simplify the prescription process. The excellent results obtained in the studies which used computer-based systems to facilitate risk assessment and prophylaxis prescription suggest that such systems may offer a promising method for achieving these 3 steps, by controlling sources of error which are inherent in variable clinician knowledge and practice. It is impossible to determine from the available evidence whether a computer-based system would be sufficiently more effective than a less technologically based alternative to justify the initial capital costs of developing and implementing such as system. It is likely that local circumstances would play a large role in determining how complex and costly the development of such a computer-based system would be. The alternative of a paper-based reminder system with active monitoring of adherence may offer an equally effective solution. However, it would appear that for any intervention to succeed in increasing the uptake of VTE prophylaxis, it needs to incorporate an iterative process so that the intervention, policy, or strategy can be improved as successive audits provide information about its effectiveness.

In terms of improving patient outcomes, in particular rates of DVT and PE, no clear evidence was found that suggests any one strategy was more effective than any other. However, this is most likely due to the limitations of the available data as previously discussed. The study designs and sample sizes used may not be sufficiently powerful to detect changes in the incidence of VTE.

Barriers and Facilitators

A number of barriers and facilitators to increasing VTE prophylaxis were evident in the included studies. Variability in clinician knowledge of risk assessment and appropriate prophylaxis and motivation regarding the need for prophylaxis appeared to play a role in the success or otherwise of implementation strategies (although such outcomes were rarely measured directly). A further complication is that there does not appear to be universal acceptance that the evidence found in guidelines or consensus statements for VTE prophylaxis practice are suitable or appropriate in all clinical situations. This appeared to be the case particularly for recommendations regarding medical patients. Although not always directly studied, the interest and enthusiasm of local clinical management for VTE prophylaxis seemed to have influenced performance in some studies, even in the control groups where no active intervention was undertaken.

Walker et al44 studied the introduction of the SIGN guidelines for VTE prophylaxis in Scotland and found that barriers to guideline implementation included a lack of supportive systems, including systems for data collection and audit; problems with individual staff responsible for implementation; a lack of acceptance of guidelines; and a perceived lack of need in particular clinical areas. On the other hand, facilitators were almost always individuals or groups of individuals who were enthusiastic and proactive and, in particular, who were given adequate time to promote good prophylaxis practice. Not surprisingly, Walker et al44 found that barriers were reported more often by hospital trusts, which were not actively implementing guidelines compared with those trusts which were. In these trusts, more facilitators than barriers were identified.

Recommendations

Research

The question of which strategies are most effective in increasing uptake of VTE prophylaxis could best be answered by cluster randomized trials comparing 1 or more strategies. At this stage, it does not seem necessary to include a placebo arm since there is sufficient evidence to suggest that passive dissemination alone will not result in adequate prophylaxis practice. Rather, research questions could focus on which of the various active strategies is more effective, in particular, comparisons of more complex (and probably more costly) interventions with simpler (and probably cheaper) interventions. A full evaluation of different strategies would ideally seek to identify barriers and facilitators to implementation so that an iterative process of improvement can occur such as was described in a number of the included studies. To study the key patient outcomes of DVT and PE rates, large multicenter studies would probably be necessary to provide sufficient power to detect these outcomes. Cost and resource use issues would need to be studied carefully and thoroughly, ensuring that the balance between the cost of implementing strategies and the potential clinical savings is taken into account, to determine whether there are cost benefits associated with particular strategies.

Clinical Practice and Policy

To effect change in VTE prophylaxis practice requires clinical leadership, improved clinician knowledge of risk assessment and prescribing, and a supportive system which removes some of the individual barriers which presently result in less-than-optimal practices. Any intervention designed to improve thromboprophylaxis practice should ideally contain the following components:

A process for demonstrating to clinicians the importance and relevance of VTE prophylaxis in their local clinical setting; for example, by conducting a local audit of current practice and presenting this to clinical staff

A process for improving clinician knowledge about VTE risk assessment and prophylaxis practice (probably through a continuing education process)

A method of reminding clinicians to assess patients for VTE risk (and possibly documentary aids to assist in the process)

A process for assisting clinicians to prescribe the appropriate prophylaxis

A method for assessing the effectiveness of any changes and for refining local policy to further improve practice; clinical audit and feedback may be the most effective method for achieving this.

Footnotes

This paper was commissioned by the National Institute of Clinical Studies (Australia) as part of its commitment to develop and transfer knowledge relating to the adoption of best evidence practice.

Reprints: Guy Maddern, FRACS, PhD, ASERNIP-S, P.O. Box 553, Stepney, South Australia, 5069, Australia. E-mail: college.asernip@surgeons.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nicolaides A, Breddin H, Fareed J, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: international consensus statement. J Vasc Bras. 2002;1:133–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism: a National Clinical Guideline. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?ss=15&doc_id=3485&nbr=2711&string=DVT. Accessed May 2003.

- 3.American College of Chest Physicians. The sixth (2000) ACCP guidelines for antithrombotic therapy for prevention and treatment of thrombosis. Chest. 2002;119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clagett G, Anderson F, Levine M, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest. 1992;102(suppl 4):391S–407S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clagett G, Anderson F, Heit J, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest. 1995;108(suppl 4):312S–334S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fletcher J, MacLellan D, Fisher C. Management and Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism: Guidelines for Practice in Australia and New Zealand. Sydney: MediMedia Communications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 7.NIH Consensus Development. Prevention of venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. JAMA. 1986;256:744–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rogers F, Cipolle M, Velmahos G, et al. Practice management guidelines for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in trauma patients: the EAST practice management guidelines work group. J Trauma. 2002;53:142–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freedman K, Brookenthal K, Fitzgerald R, et al. A meta-analysis of thromboemobolic prophylaxis following elective total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (America). 2000;82:929–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macklon N, Greer A. Thromboprophylaxis in Obstetrics and Gynaecology (PACE no. 95/10). London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Health and Medical Research Council, Commonwealth of Australia. A guide to the Development, Implementation And Evaluation Of Clinical Practice Guidelines. Canberra, ACT: AusInfo; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson F, Brownell Wheeler H, Goldberg R, et al. Changing clinical practice: prospective study on the impact of continuing medical education and quality assurance programs on the use of prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:669–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durieux P, Nizard R, Ravaud P, et al. A clinical decision support system for prevention of venous thromboembolism: effect on physician behavior. JAMA. 2000;283:2816–2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang A, Barber N, Northeast A. Deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis protocol: needs active enforcement. Ann Royal Coll Surg Engl. 2000;82:69–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pritts T, Nussbaum M, Flesch L, et al. Implementation of a clinical pathway decreases length of stay and cost for bowel resection. Ann Surg. 1999;230:728–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ageno W, Squizzato A, Ambrosini F, et al. Thrombosis prophylaxis in medical patients: a retrospective review of clinical practice patterns. Haematologica. 2002;87:746–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmad H, Geissler A, MacLellan D. Deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis: are guidelines being followed? ANZ J Surg. 2002;72:331–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arnold D, Kahn S, Shrier I. Missed opportunities for prevention of venous thromboembolism: an evaluation of the use of thromboprophylaxis guidelines. Chest. 2001;120:1964–1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bratzler D, Raskob G, Murray C, et al. Underuse of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis for general surgery patients: physician practices in the community hospital setting. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1909–1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burns P, Wilsom R, Cunningham C. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis used by consultant general surgeons in Scotland. J Royal Coll Surg Edin. 2001;46:329–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Villemur B, Bosson J, Diamand J. Deep venous thrombosis (DVT) after hip or knee prosthesis: evaluation of practices for prevention and prevalence of DVT on Doppler ultrasonography. J Mal Vasc. 1998;23:257–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aouizerate P, Mabiala H, Perrot F, et al. Preventive treatment of thrombosis: audit on heparin prescription. Therapie. 1998;53:101–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fagot J, Flahault A, Fodil M, et al. Impact of expert recommendations on LMWH venous thromboembolism prophylaxis for non-surgery patients on physician prescriptions. Presse Med. 2001;30:203–208.12385051 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harinath G, St John P. Use of a thromboembolic risk score to improve thromboprophylaxis in surgical patients. Ann Royal Coll Surg Engl. 1998;80:347–349. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macdonald D, Bhalla P, Cass W, et al. Computerized management of oral anticoagulant therapy: experience in major joint arthroplasty. Can J Surg. 2002;45:47–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McEleny P, Bowie P, Robins J, et al. Getting a validated guideline into local practice: implementation and audit of the SIGN guideline on the prevention of deep vein thrombosis in a district general hospital. Scott Med J. 1998;43:23–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller G, Lewis W, Sainsbury J, et al. Morbidity of varicose vein surgery: auditing the benefit of changing clinical practice. Ann Royal Coll Surg Engl. 1996;78:345–349. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oghoetuoma J, Shahid N, Nuttall I. Audit on the use of thromboprophylaxis during caesarean section. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;21:138–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patterson R. A computerized reminder for prophylaxis of deep vein thrombosis in surgical patients. Proc AMIA Symp. 1998;573–576. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor G, McKenzie C, Mires G. Use of a computerised maternity information system to improve clinical effectiveness: thromboprophylaxis at caesarean section. Postgrad Med J. 2000;76:354–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams H, Macdonald D. Audit of thromboembolic prophylaxis in hip and knee surgery. Ann Royal Coll Surg Engl. 1997;79:55–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Birks M, Aiono S, Magee T, et al. A simple way to improve DVT protocol compliance. Phlebology. 2002;16:121–124. [Google Scholar]

- 33.George B, Nethercliff J, Cook T, et al. Protocol violation in deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis. Ann Royal Coll Surg Engl. 1998;80:55–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bridges G, Lee M, Jenkins K, et al. Expedited discharge in trauma patients requiring anticoagulation for deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis: the LEAP program. J Trauma. 2003;54:232–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Devlin J, Tyburski J, Moed B. Implementation and evaluation of guidelines for use of enoxaparin as deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis after major trauma. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21:740–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frankel H, FitzPatrick M, Gaskell S, et al. Strategies to improve compliance with evidence-based clinical management guidelines. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;189:533–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hall L, Eccles M. Case study of an inter-professional and inter-organisational programme to adapt, implement and evaluate clinical guidelines in secondary care. Clin Perf Qual Health Care. 2000;8:72–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hohlt T. Deep-vein thrombosis prevention in orthopaedic patients: affecting outcomes through interdisciplinary education. Orthopaed Nurs. 2000;19:73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCarthy M, Byrne G, Silverman S. The setting up and implementation of a venous thromboembolism prophylaxis policy in clinical hospital practice. J Eval Clin Prac. 1998;4:113–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Byrne G, McCarthy M, Silverman S. Improving uptake of prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in general surgical patients using prospective audit. BMJ. 1996;313:917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peterson G, Drake C, Jupe D, et al. Educational campaign to improve the prevention of postoperative venous thromboembolism. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1999;24:279–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ryskamp R, Trottier S. Utilization of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in a medical-surgical ICU. Chest. 1998;113:162–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stratton M, Anderson F, Bussey H, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: adherence to the 1995 American College of Chest Physicians consensus guidelines for surgical patients. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walker A, Campbell S, Grimshaw J, et al. Implementation of a national guideline on prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism: a survey of acute services in Scotland. Health Bull. 1999;57:141–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lowe, G, Greer 1, Cooke T, et al. Risk of and prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in hospital patients. BMJ. 1992;305:567–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]