Abstract

Objective:

A subgroup of patients with intractable constipation has persistent dilatation of the bowel, which in the absence of an organic cause is termed idiopathic megabowel (IMB). The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate the published outcome data of surgical procedures for IMB in adults.

Methods:

Electronic searches of the MEDLINE (PubMed) database, Cochrane Library, EMBase, and Science Citation Index were performed. Only peer-reviewed articles of surgery for IMB published in the English language were evaluated. Studies of all surgical procedures were included, providing they were performed on 3 or more patients, and overall success rates were documented. Studies were critically appraised in terms of design and methodology, inclusion criteria, success, mortality and morbidity rates, and functional outcomes.

Results:

A total of 27 suitable studies were identified, all evidence was low quality obtained from case series, and there were no comparative studies. The studies involved small numbers of patients (median 12, range 3–50), without long-term follow-up (median 3 years, range 0.5–7). Inclusion of subjects, methods of data acquisition, and reporting of outcomes were extremely variable. Subtotal colectomy was successful in 71.1% (0%–100%) but was associated with significant morbidity related to bowel obstruction (14.5%, range 0%–29%). Segmental resection was successful in 48.4% (12.5%–100%), and recurrent symptoms were common (23.8%). Rectal procedures achieved a successful outcome in 71% to 87% of patients. Proctectomy, the Duhamel, and pull-through procedures were associated with significant mortality (3%–25%) and morbidity (6%–29%). Vertical reduction rectoplasty (VRR) offered promising short-term success (83%). Pelvic-floor procedures were associated with poor outcomes. A stoma provided a safe alternative but was only effective in 65% of cases.

Conclusions:

Outcome data of surgery for IMB must be interpreted with extreme caution due to limitations of included studies. Recommendations based on firm evidence cannot be given, although colectomy appears to be the optimum procedure in patients with a nondilated rectum, restorative proctocolectomy the most suitable in those with dilatation of the colon and rectum, and VRR in those patients with dilatation confined to the rectum. Appropriately designed studies are required to make valid comparisons of the different procedures available.

A proportion of patients with intractable constipation who fail to respond to nonsurgical intervention have persistent dilatation of the bowel without obvious cause and are described as having idiopathic megabowel. This systematic review evaluated the published outcome data of available surgical procedures, such as subtotal and segmental colectomy, restorative proctocolectomy, and rectal surgery, for idiopathic megarectum and megacolon.

The management of patients with intractable constipation who fail to respond to nonsurgical intervention continues to represent a challenge for general and colorectal surgeons. Disorders of gastrointestinal function, including those characterized by constipation, are common conditions1 that cause considerable suffering and have a major impact on quality of life,2 yet our understanding, and hence ability to treat such conditions, remains limited. However, identification of the different underlying abnormalities that result in the end symptom of constipation may be crucial to successful management, since it allows rational, rather than empirical, treatment. On the basis of bowel diameter, patients with functional constipation can be divided into 2 distinct groups;3 those with persistent dilatation are described as having megabowel.4 Such dilatation may occur secondary to Hirschsprung disease, anorectal obstruction, or disorders of the endocrine or central nervous system.5 However, frequently there is no obvious cause, idiopathic megabowel (IMB), and the surgical options for this condition forms the basis of this review.

The incidence of IMB is unknown, although it affects males and females equally.3 It is characterized by recurrent fecal impaction that may begin during childhood or adult life.6 The dilatation may affect various segments of the bowel, resulting in megacolon (IMC), megarectum (IMR), or both (IMB), and although is so gross that it is often evident on examination or plain radiography of the abdomen or during laparotomy, a formal diagnosis may be made during contrast enema, when the rectal diameter at the pelvic brim is greater than 6.5 cm.7 Despite the etiology being unknown, evaluation of anorectal function has revealed that patients with IMB have excessive laxity (increased compliance),8,9 hypomotility,10 and sensory dysfunction of the rectum.3,9 Furthermore, patients also have impaired rectal evacuatory function,3,9 often with secondary delay in colonic transit.11

Patients with IMB are managed conservatively in the first instance. Indeed, it is claimed that the majority of patients can be successfully managed nonsurgically.3 However, medical treatment may fail to alleviate symptoms in 50% to 70% of patients,12,13 may be poorly tolerated,14 and must be continued lifelong to prevent recurrence of symptoms.6 Furthermore, it fails to achieve a restoration of the rectal caliber to normal, even following several years of medical therapy.15 More recently, the role of behavioral retraining, incorporating biofeedback, has been explored,16 although only 6 patients were evaluated in the short term, and clinical and physiologic parameters were not rigorously compared before and after intervention.

Consequently, many patients are forced to seek a surgical solution to their symptoms when conservative therapy is ineffective or poorly tolerated.14 In addition, certain patients require surgical intervention due to the development of complications of IMB, such as recurrent sigmoid volvulus.4,17 The aim of this article was to perform a systematic review of the published outcome data of surgical procedures for IMB in adults.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search Strategy

Electronic searches of the MEDLINE (PubMed) database, Cochrane Library, EMBase, and Science Citation Index from the start of each of their time frames through to April 2004 were performed to identify original published studies of surgery for IMB (IMR and/or IMC). The Annals of Surgery, British Journal of Surgery, Diseases of the Colon and Rectum, and the International Journal of Colorectal Disease (January 1991 to April 2004) and Colorectal Disease (January 1999 to April 2004) were specifically hand searched. Reference lists of all relevant articles were searched for further studies, as was the relevant chapter in Surgery of the Anus, Rectum & Colon.18 The search terms used were idiopathic AND (megabowel OR IMR OR IMC) NOT (toxic OR congenital) AND (surg* OR operat* OR manage* OR treat*) where * is a truncation symbol that retrieves words beginning with that root (eg, surg* will identify surgery, surgical etc).

Selection Criteria

Of the identified studies, only those published in the English language describing randomized and nonrandomized controlled trials or case series in adults were included. Only full peer-reviewed articles were selected, as published abstracts did not provide sufficient data relating to patient selection and evaluation or methods of outcome assessment. Studies of all surgical procedures for IMB were included, providing they supplied information on success rates and were performed in patients documented as having dilated bowel, for which no apparent cause could be found (ie, IMB). Studies examining exclusively pediatric patients, or patients with secondary dilatation (eg, Hirschsprung disease, obstruction) were excluded. In general, studies of surgery for constipation that incorporated a small proportion of patients with IMB were not included, as the outcome of specific patients with IMB could frequently not be determined. However, 3 such studies with explicit description of results were included.19–21 Furthermore, case reports, and case series containing less than 3 patients were excluded.22–24 Similarly, the outcomes of specific procedures were not considered if performed in less than 3 patients within any individual series.

Validity Assessment

The methodological quality of the selected studies was assessed according to hierarchies of evidence and critical appraisal checklists.25 However, since relatively few studies assessing outcome of surgery for IMB were identified, all were included irrespective of their quality.

Data Extraction and Analysis

General data relating to study design, number of patients (total number in series/number managed surgically) and length of follow-up were recorded. In addition, specific details about the study population were collected to establish the degree of the bowel dilatation (IMR/IMC/IMB) and the “accuracy” of the diagnosis of IMB; specifically, the method of diagnosis of megabowel (eg, in accordance with recognized criteria on contrast study7) and the methods used to exclude a cause for dilatation (eg, the presence of the rectoanal inhibitory reflex26 or ganglion cells on preoperative rectal biopsy to exclude Hirschsprung disease). The success, mortality and morbidity rates for individual procedures were recorded. More specifically, the methods of determination of success (patient judgment/clinical symptoms/both) and data acquisition (questionnaire/patient interview/utilization of symptom scoring systems27,28) were documented. Functional results and the frequency with which they were objectively measured using anorectal physiologic investigation were noted when available. For individual procedures, the overall outcome rates were calculated by recording the number of events as a percentage of the total number of patients undergoing that procedure where the outcome was reported. Outcomes were only included in the analysis if they were specifically stated, and no assumptions were made if the data were missing; specifically, when a particular rate was not disclosed it was not assumed to be zero. Data were evaluated on an intention-to-treat basis.

RESULTS

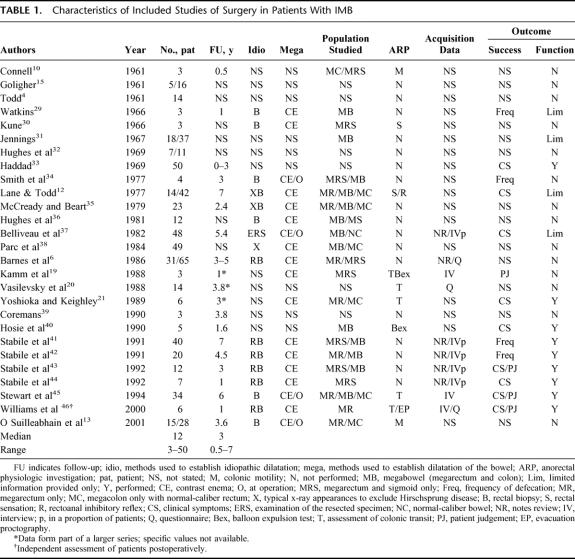

The search identified 27 studies, published between 1961 and 2001, specifically assessing the outcome of surgery in patients with IMB (Table 1). All evidence was low quality obtained from case series. No study was controlled with respect to the outcome from other surgical or medical interventions, or no treatment. Most of the studies of surgical outcome for IMB were retrospective in nature. Furthermore, such studies usually involved small numbers of patients (median, 12; range, 3–50) and none performed long-term follow-up of patients (median follow-up, 3 years; range, 0.5–7).

TABLE 1. Characteristics of Included Studies of Surgery in Patients With IMB

Inclusion of Subjects

A diagnosis of megabowel was made in all subjects using contrast enema in only 14 series (52%), and in the majority of subjects in a further 4 studies (15%), only 5 of which made use of recognized diagnostic criteria7 (out of a possible 13 [38%] performed after the introduction of such criteria). Closer inspection of the methods used to exclude a cause for dilatation revealed that only 14 studies (52%) used either the presence of the rectoanal inhibitory reflex26 or ganglion cells on preoperative rectal biopsy to exclude Hirschsprung disease. No details regarding method of diagnosis of megabowel or exclusion of cause were stated in 9 of 27 (33%) and 11 of 27 (41%) studies, respectively. Differing proportions of patients with varying degrees of proximal bowel dilatation (IMR only/megabowel, etc) were included (Table 1).

Evaluation of Patients

Objective physiologic assessment of function was performed in only 10 of the 27 studies (37%) (Table 1). In most instances, such investigations were only performed in a proportion of patients undergoing surgery, and with the exception of 2 studies,19,46 were not comprehensive and did not include assessment of colonic transit time and rectal evacuatory function.

Methods Used in Outcome Assessment

The method of data acquisition was not stated in the majority of studies, and postoperative patient interview was attempted in only 8 studies (30%). Standardized questionnaires, potentially offering a more objective means of data collection, were only used in 3 studies (11%). Validated scoring systems27,28 were not used. Only 1 study assessed the outcome objectively using personnel not involved in the surgical care of the patients.46 Data were not collected blindly in any study.

The method by which the outcome was judged to have been successful, allowing meaningful interpretation to be made, was only provided in 14 studies (52%). Success was assessed on the basis of bowel frequency alone in 4 studies, clinical symptoms alone in 6 studies, patient judgment alone in 1 study, and a combination of clinical symptoms and patient judgment in 3 studies (Table 1). Measures of functional results postoperatively were only provided in 13 series (48%) (limited information in 5 of these). No study examined the impact of surgery on quality of life. Reporting of postoperative mortality and morbidity of individual procedures was also variable. Finally, objective measurement of function, using physiologic investigation, was performed in only 1 study following surgery.46

Surgical Options

The studies identified evaluated the following surgical procedures for IMB.

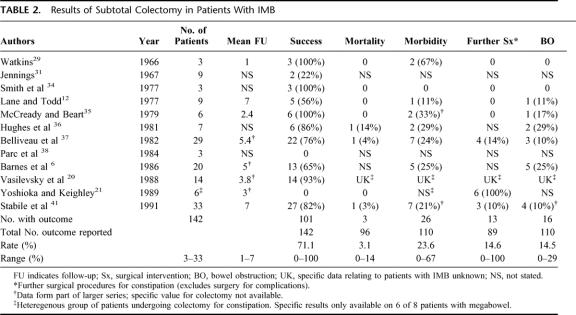

Subtotal Colectomy

The published success rates of subtotal colectomy were highly variable, ranging from 0 to 100%, with 101 successful outcomes reported out of a total of 142 procedures performed (71.1%) (Table 2). The number of patients studied was small (median, 8 patients; range, 3–33), with a relatively short follow-up period (median, 4.4 years; range, 1–7). However, several studies have included larger numbers of patients and may provide a more accurate measure of success. Belliveau et al37 performed a retrospective analysis of patients undergoing colectomy. They defined success as “the relief of symptoms of abdominal pain and obstipation in patients not requiring laxatives,” which was obtained in 15 of 20 patients undergoing ileosigmoid anastomosis (ISA) and 7 of 9 undergoing ileorectal anastomosis (IRA); the remaining 7 patients (24%) all developed recurrent constipation within 5 years.37 Barnes et al6 performed colectomy and cecorectal anastomosis (CRA) in 14 patients, good results were noted in 7 (50%) with regular bowel actions and no soiling, 2 were improved following surgery, 4 remained constipated, and 1 was lost to follow-up. A further 6 patients underwent colectomy and IRA, 4 (67%) of whom achieved improvement and regular bowel habits; 1 remained constipated, and the other patient was lost to follow-up.6 They concluded that about two thirds of patients benefit from colectomy.

TABLE 2. Results of Subtotal Colectomy in Patients With IMB

Vasilevsky et al20 reported colectomy in a cohort of patients with constipation, 14 of whom had IMB. A successful outcome was obtained in 93% of patients, although specific details, including the method used to assess outcome, were not provided.20 Stabile et al41 studied patients retrospectively who had previously undergone colectomy for megabowel at St Mark's Hospital, and found that 3 patients (10%) developed recurrent constipation (defined as <2 bowel movements per week) following colectomy. However, 17% of all patients still required laxatives, and 7% continued to suffer with fecal impaction following surgery.41

Other reports of colectomy in patients with IMB are restricted to small numbers of patients. Lane and Todd12 studied 9 patients out of a series of 42 who underwent colectomy. CRA was performed in 5 cases; success was achieved in 3 patients (60%) who were asymptomatic and no longer required laxatives. Three patients underwent colectomy and IRA, 1 (33%) of which was successful, and another patient, who had an IMC with normal rectum, underwent successful colectomy and ISA.12 Smith et al34 reported 100% success and no complications in 3 patients undergoing colectomy and IRA or CRA anastomosis. McCready and Beart35 performed 6 colectomies with ISA or IRA in patients refractory to medical management and with impaired quality of life, all of whom were “significantly improved” following surgery. In contrast, a mediocre outcome was achieved in all 3 patients undergoing subtotal colectomy with ISA in another study.38

The reported mortality rates ranged from 0% to 14%, with 3 deaths occurring in a patient pool of 96 (3.1%) (Table 2). Morbidity events following subtotal colectomy were also relatively common, and when reported, occurred in 26 of 110 procedures (23.6%; range, 0%-67%). Stabile et al41 reported 1 death due to abdominal sepsis, 4 cases of bowel obstruction requiring laparotomy, 2 wound abscesses, and 2 incisional herniae in a series of 33 patients, and Belliveau et al37 found a mortality of 2% and a high morbidity of 21%, with 6 of 29 patients having to undergo repeat surgery to address complications. The high associated morbidity was most commonly related to anastomotic problems,37 and particularly, the subsequent development of recurrent bowel obstruction, which occurred overall in 16 of 110 procedures (14.5%), with a range of 0% to 29% (Table 2), and usually required surgical management.35–37,41 The incidence of bowel obstruction following surgery is higher than that expected for colectomy for neoplastic or inflammatory disease, although the reasons for this are not clear.36

Recurrence of constipation was a significant problem following subtotal colectomy, resulting in 14.5% (range, 0%-100%) of patients requiring additional surgical intervention (Table 2). Colectomy and IRA has been recommended as the procedure of choice to prevent recurrence of constipation.39,41 However, Yoshioka and Keighley21 reported specific results in 6 of 8 patients who underwent subtotal colectomy and IRA, all of whom had IMC with a rectum of normal diameter. All developed recurrent constipation secondary to dilatation (IMR) and dysfunction of the rectum that ultimately required restorative proctocolectomy.21 Therefore, retention of the rectum itself in IRA may result in recurrence of symptoms due to dilatation.12,21,34

Poor functional outcomes, where documented, related to frequent and loose stools, and were reported in 7% to 33% of patients,12,34,37,41 although this proportion was as high as 78% in one study.31 Similarly, continued abdominal pain and distension, presumably secondary to recurrent dilatation of the rectal and cecal remnant, was reported postoperatively in up to one third of patients,12,34 and associated fecal incontinence in up to 20% of patients.41 However, the incidence of abdominal pain and distension may represent an absolute reduction given the high overall incidence (approximately 50%-80%) of these symptoms in patients with IMB.3,45 Only 1 study compared the frequency of symptoms before and after surgery, showing reductions in abdominal pain from 100% to 36%, abdominal distension from 85% to 39%, and incontinence from 35% to 17%.41

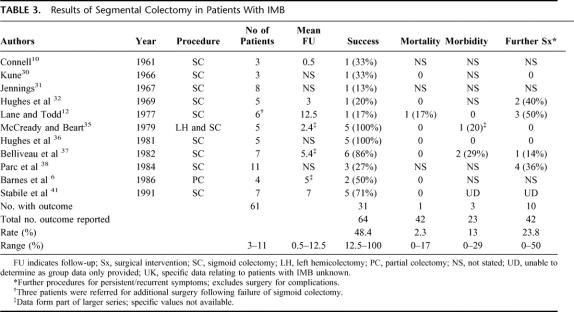

Segmental Colectomy

In terms of segmental resection, the outcome of sigmoid colectomy was most commonly studied (Table 3). However, in common with other procedures for IMB, studies were limited to small numbers of patients (median 5 patients) and, at most, medium-term follow-up postoperatively (median 5 years). Analyses of results were made more confusing, due to a tendency to summarize the outcome of segmental with subtotal resection.6,12,37,41

TABLE 3. Results of Segmental Colectomy in Patients With IMB

The overall success rate of segmental resection was 48.4% (12.5%-100%), although there was an interesting dichotomy, with some studies reporting a very favorable outcome, while others, a very poor outcome (Table 3). McCready and Beart35 performed left hemicolectomy involving resection of the descending and sigmoid colon and rectosigmoid in 5 patients, all of whom were significantly improved following surgery. Stabile et al41 reported the outcomes of 7 sigmoid resections, 5 in patients with dilatation of the entire colon and rectum, and 2 with dilatation restricted to the rectosigmoid. Of the 6 patients available for follow-up, a bowel frequency of >2 per week was obtained in 5 patients (83%).

In marked contrast, Jennings31 achieved a good result in only 1 of 8 patients (12.5%) undergoing sigmoid colectomy; the remainder all developed recurrent impaction within 6 months. Similarly, Kune30 achieved a favorable outcome in only 1 of 3 patients (33%) following a Paul-Mikulicz type sigmoid colectomy. One patient was troubled with persistent abdominal pain and distension postoperatively, and in view of this stoma reversal was never attempted in the remaining patient.30 Lane and Todd12 had to perform additional resections in 3 patients who had previously undergone sigmoid colectomy without any significant improvement. Of 3 further sigmoid resections they performed as primary procedures, only 1 was successful, and a further patient died of large-bowel obstruction secondary to impacted feces.12 Parc et al38 also only achieved good results in 3 of 11 (27%) patients, 3 had a mediocre outcome, and the remaining 4 had a bad outcome and subsequently underwent a Duhamel procedure. The reasons for the above disparity in results are not clear. Interestingly, it even appears to occur within the same institution. Hughes et al32 initially achieved only a 20% success rate following segmental resection, although the same group went on to report 100% success rates in a later series of patients.36

Only 1 study reported a mortality rate, giving an overall mortality rate of 2.3%.12 The overall morbidity rate of the procedure was 13% (range 0%-29%), although 23.8% of patients required further surgical intervention for recurrence of dilatation and symptoms secondary to impaction of feces, which occurred immediately following segmental resection and up to 12 years later.32

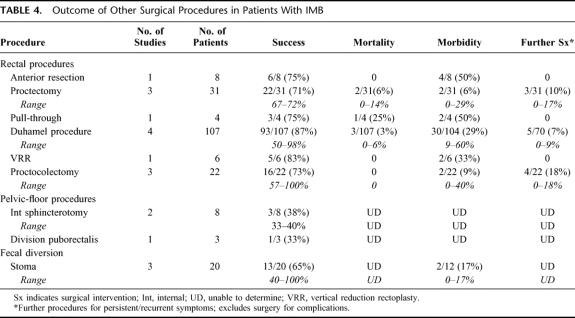

Rectal Procedures

The following procedures that address the rectum have been performed in patients with IMB. For each procedure, the outcome parameters are shown in Table 4.

TABLE 4. Outcome of Other Surgical Procedures in Patients With IMB

Anterior Resection

Partial resection of the rectum with colorectal anastomosis in patients with IMB has been evaluated in only 1 study,35 presumably because it does not fully address the rectal dilatation, which usually extends down to the pelvic floor. Six of 8 patients (75%) had a good outcome and no longer required medication, but there was a high associated morbidity (50%), including anastomotic narrowing requiring 2 separate revisions (n = 1), small-bowel obstruction requiring surgical intervention (n = 2), and wound infection (n = 1).35

Proctectomy

Three studies have examined the outcome of proctectomy for IMB in a total of 31 patients.13,44,45 A successful outcome was reported in 22 patients (71%; range, 67%–72%), although there was an associated mortality rate of 6.5% (range, 0%–14%). Two of the 31 patients experienced morbidity events (6.5%; range, 0%–29%), and 3 patients (9.7%) required further surgical intervention for recurrence of constipation (range, 0%–17%). Stabile et al44 reported resection of the distal colon and rectum with coloanal anastomosis with success in 5 of 7 patients (71%) with IMR, at a mean follow-up of 1 (0.5–2) year. However, there was 1 death (14%) secondary to the consequences of massive hemorrhage and a morbidity of 29% secondary to pelvic sepsis and a rectovaginal fistula, both of which required temporary fecal diversion.44 Stewart et al45 performed proctectomy and coloanal anastomosis in 18 patients with IMR (with or without megasigmoid), with colonic J pouch formation in 8. After a median follow-up of 6 (0.75–16) years, a good result with essentially normal bowel function and satisfactory continence, was achieved in 13 patients (72%).45 There was 1 death (6%) in a patient secondary to aspiration pneumonia complicating small-bowel obstruction, but no other major complications, although 3 patients required further surgery for recurrent constipation (2, formation of ileostomy; 1, restorative proctocolectomy).45

Recurrence of constipation secondary to dilatation or dysfunction of the proximal colon can occur in 14% to 17% of patients following proctectomy.44,45 However, when proctectomy and coloanal anastomosis was performed in 6 patients with IMR and normally functioning proximal bowel, no patient developed recurrent constipation or required laxatives or enemata, although only 4 (67%) had good functional results, as 1 patient experienced fecal urgency and occasional incontinence, and another developed ulcerative colitis.13

Endorectal Pull-Through

This procedure was only performed in 1 study, where McCready and Beart35 performed a Swenson endorectal pull-through of the descending or sigmoid colon down to the perineum in 4 patients. One patient died due to a pelvic abscess and associated generalized peritonitis, a second patient developed a pelvic abscess and an anastomotic stricture, both requiring surgical intervention, and another patient developed urinary retention that required prolonged catheterization.35 The surviving 3 patients all had an excellent ultimate outcome and no longer required laxatives.35 However, the high morbidity makes it an unattractive option for this condition.

Duhamel Procedure

Four studies have examined the outcome of the Duhamel procedure for IMB in a total of 107 patients.6,33,38,42 A successful outcome was reported in 93 patients (87%), although the range was extremely variable (50%-98%). Furthermore, there was an associated mortality rate of 3% (range, 0%-6%) and a morbidity rate of up to 60%. Recurrence of constipation resulted in 5 patients (7%) requiring further surgical intervention. Haddad33 performed 50 procedures using a modified technique, and reported normal bowel function in all but 1 patient (2%), who developed recurrent impaction. However, there were 3 deaths (6%) and significant complications (32%) related to the procedure.33 There were 6 (12%) anastomotic leaks (rectocolic anastomosis, n = 1; rectal stump, n = 5) and 1 stricture (2%) and 2 episodes of necrosis of the perineal colostomy (4%). Furthermore, 2 patients (4%) developed pelvic abscesses and 4 (8%), suppuration from the suprapubic drain sites. Moreover, 1 of 17 male patients (6%) questioned experienced impotence and sexual dysfunction postoperatively.33

Parc et al38 performed 34 cases (27 as a primary procedure and 7 following failure of other procedures) without mortality. Good results were reported in all but 2 of the patients (6%), leading the authors to conclude that this should be the operation of choice for patients with idiopathic IMC with or without IMR. However, 2 patients developed pelvic abscesses, and another patient developed an anastomotic stricture.38 Barnes et al6 reported a successful outcome in 2 of 3 patients (67%) following a Duhamel procedure.

In contrast, Stabile et al42 only achieved a successful result, with normalization of bowel frequency, in 50% of 20 cases. Functional outcome was poor in 2 patients (10%) with diarrhea and 8 patients (40%) with incontinence postoperatively.42 Furthermore, many patients required additional surgical intervention for persistent constipation (25%) or bowel obstruction (20%). Moreover, the morbidity associated with the procedure was extremely high, with 30% developing fecal or rectovaginal fistulae and pelvic abscesses and anastomotic strictures each occurring in up to 15% of cases.42

Vertical Reduction Rectoplasty (VRR)

VRR is a novel procedure that involves transection of the dilated rectum in a vertical direction along its antimesenteric border and excision of the anterior portion, thus reducing rectal capacity.46 It was evaluated in one study by an independent investigator who was not part of the operative team and, unlike previous studies, involved the objective assessment of the impact of surgery on anorectal function using physiologic tests. The procedure was associated with no mortality and minimal early morbidity, although 1 patient (17%) developed a small-bowel fistula that required excision.46 Significant improvements in bowel frequency without the need for laxatives or enemata and satisfaction with surgery were obtained in 5 of 6 patients (83%), with restoration of the rectal perception of urge to defecate in all at 1 year following surgery.46 Furthermore, objective improvement in parameters of anorectal physiologic function were noted with a sustained significant reduction in rectal capacity, normalization of rectal sensory function in all patients, and improvement in rectal evacuatory function.46

Restorative Proctocolectomy

A successful outcome was reported in 16 of 22 patients (73%; range, 57%-100%), following restorative proctocolectomy. None of the studies reported any mortality, although the morbidity rates were extremely variable (0%-40%). Hosie et al40 were the first to perform this procedure in patients with IMR and IMC. All 5 patients obtained complete relief of their symptoms of constipation and abdominal pain and distension. However, the procedure was associated with a high rate (40%) of anastomotic leaks requiring drainage, with 1 patient going on to develop recurrent small-bowel obstruction.40 Frequency of defecation was also a problem postoperatively (median bowel movements 5 per day), and 60% of patients suffered with nocturnal soiling.40 Stewart et al45 performed restorative proctocolectomy, with J-pouch formation in 14 patients without complication. Of these, 12 (86%) had a bowel frequency of less than 7 per day and were continent, 1 patient had “minor” soiling, and the final patient required graciloplasty for frank incontinence. However, 4 patients (18%) eventually underwent pouch excision and ileostomy formation for persistent abdominal pain and distension.45 O'Suilleabhain et al13 performed restorative colectomy in 3 patients with IMR, with either associated IMC or impaired proximal colonic motility, with “satisfactory” pouch function.

Pelvic Floor Procedures

Internal Sphincterotomy

The outcome of internal sphincterotomy was evaluated in 2 studies37,38 and was found to be beneficial in only 1 of 3 patients when performed as a secondary procedure37 and in 2 of 5 patients when performed as a primary procedure.38

Puborectalis Division

Kamm et al19 performed lateral division of the puborectalis muscle in 3 patients with IMR and megasigmoid as part of series of patients with disordered evacuation. Specific results are not given, although only 1 patient (33%) with IMR reported an improvement following the procedure. Overall, puborectalis division was not associated with improvement in bowel frequency or clinical symptoms, and the majority of the patients still demonstrated physiologic evidence of paradoxical contraction of the puborectalis and an inability to evacuate.19

Fecal Diversion

Three studies have examined the outcome of stoma formation.13,15,43 Success rates varied from 40% to 100%, and although there was no associated mortality, there was a morbidity of up to 17% (Table 4). Goligher15 reported a satisfactory outcome in all 3 patients following colostomy formation. O'Suilleabhain13 reported resolution of symptoms in 2 of 5 patients (40%) who underwent temporary ileostomy formation prior to undergoing definitive surgery. Stabile et al43 reported the results of stoma formation in 12 patients. Of the 8 patients who had a colostomy, although relief of symptoms was obtained in 6 patients (75%) where the stoma was created using proximal bowel of normal caliber, an eventual successful outcome was obtained in only 50% as 2 patients could not tolerate the stoma and underwent alternative surgical procedures.43 The remaining 2 patients with dilatation of the entire large bowel developed fecal impaction proximal to the colostomy and subsequently developed a prolapsing stoma.43 Of the 4 patients who had an ileostomy, constipation was relieved in all, but 3 continued to be troubled with abdominal pain and distension.43

DISCUSSION

This systematic review has evaluated the outcomes of various surgical procedures for IMB. However, all evidence was low quality obtained from case series, no study was controlled, and most were retrospective in nature. Consequently, data relating to surgical outcome must be interpreted with considerable caution. Furthermore, such studies usually involved small numbers of patients, making it difficult to draw statistically sound conclusions. However, the relative infrequency of surgery for this condition means that conducting “adequately powered” randomized controlled trials comparing different surgical and/or nonsurgical interventions is impractical. Moreover, no studies performed long-term follow-up of patients.

The inclusion of heterogeneous groups of subjects undergoing surgery also makes interpretation of results problematic. All publications that explicitly stated that surgery was performed in patients with IMB were included in this review. However, approximately half of all studies failed to confirm the presence of megabowel using contrast study, and most did not used recognized diagnostic criteria,7 or to exclude a cause for the dilatation (eg, the presence of the rectoanal inhibitory reflex26 or ganglion cells on rectal biopsy to exclude Hirschsprung disease). Furthermore, the comparison of outcome between studies may not be appropriate due to a lack of homogeneity of the populations studied and the inclusion of differing proportions of patients with varying degrees of proximal bowel dilatation (eg, IMR/IMC). Currently, it is not known whether the degree of proximal extension of dilatation is dependent on different pathophysiologies or etiologies. However, selection of a more homogeneous population of patients, with respect to the degree of bowel dilatation and/or dysfunction, would allow more meaningful comparison of surgical outcomes.

Direct comparison of the outcomes of different surgical procedures is also restricted by inconsistencies relating to the acquisition, interpretation, and reporting of specific outcome parameters. Overall “success rates” are crucial to the evaluation of a procedure. However, the method by which the outcome was judged to have been successful, allowing meaningful interpretation to be made, was only provided in 52% of studies. Measures of functional results are also important when assessing individual surgical procedures, but details relating to postoperative bowel function were not provided in the majority of studies. Furthermore, as patients with IMB have a disturbance of bowel function,3,9 it would not be unreasonable to expect objective measurement of function to be performed postoperatively. However, physiologic investigation was performed in only 1 study following surgery.46

The methods of data acquisition were also inconsistent. The reporting and severity of symptoms experienced by patients with IMB may be variable, and thus, standardized questionnaires may offer a more accurate means of data collection. In recent years, validated scoring systems have been devised to objectively assess symptoms,27,28 but these were not used in any study. No study examined the impact of surgery on quality of life. This lack of objective measurement of both clinical symptoms and anorectal physiologic function may also help to explain the highly variable reported results of surgery for IMB noted in this review.

The available surgical options for constipation are essentially similar, irrespective of bowel diameter, and involve either colon and/or rectal resection, pelvic floor procedures, or fecal diversion.47 However, surgery is even more challenging in patients with megabowel48 since adequate bowel preparation is often impossible40; the dilated rectum fills the entire pelvis, making access difficult; the presence of numerous and dilated rectal vessels makes mobilization hazardous; the rectal wall may be grossly thickened; and there is a marked discrepancy between the diameters of the bowel forming the end-to-end anastomosis.40,44 An alternative surgical approach in constipated patients involves the creation of a colonic conduit that allows antegrade irrigation to achieve colonic and rectal emptying,49 and it appears that placement in the transverse colon, enabling irrigation of more of the colon, offers superior results to placement in the sigmoid colon.50 However, neither of these procedures has been applied to adult patients with IMB.

Subtotal Colectomy

Subtotal colectomy (and ISA, CRA, or IRA) was the most widely applied operation for IMB. The rationale for this procedure is based on the finding that many patients have delayed colonic transit8,11 and that colonic resection allows the associated pelvic floor dysfunction to be overcome by promoting a more liquid stool, which is easier to pass.39 The premise that subtotal colectomy is a simple procedure with low morbidity in patients with IMB51 must be seriously challenged on the basis of the above data since there is a mortality of up to 14%36 and high morbidity of approximately 25%; patients undergoing this procedure must be warned of the high risk of recurrent bowel obstruction.

Subtotal colectomy appears to be successful in approximately 70% of patients with IMB, although such results were highly variable, ranging from 0% to 100%.21,35 Recurrence of constipation is a significant problem following subtotal colectomy, resulting in approximately 15% of patients requiring additional surgical intervention. Distension of the retained cecum39,41 in CRA and the sigmoid colon in ISA37 may predispose to the development of symptoms of abdominal distension, impaired evacuation, and recurrent constipation, and necessitate further, more aggressive resection.37,41 Consequently, colectomy and IRA has been recommended as the procedure of choice to prevent recurrence of constipation.39,41 However, retention of the cecum (CRA) preserves its absorptive capacity and may reduce the likelihood of frequent, loose stools and episodes of incontinence.12 Furthermore, retention of the rectum itself in IRA may result in recurrence of symptoms due to dilatation.12,21,34 As most studies did not stratify results according to the type of anastomosis performed, firm statistical conclusions regarding the optimum choice cannot be made, although it is likely that IRA is associated with lower rates of recurrence of constipation.

Segmental Colectomy

The extent of the proximal dilatation in patients with megabowel is variable.12,35,41 The rationale of a segmental resection is based on the assumption that only dilated and abnormally functioning bowel is resected, while nondilated, normally functioning bowel is retained in an attempt to preserve function. Segmental appears to achieve inferior results compared with subtotal colectomy, with an overall success rate of approximately 50%, with approximately 25% of patients requiring additional resections. Consequently, subtotal colectomy may be preferred,12,32,41 particularly in patients undergoing surgery due to sigmoid volvulus, as concomitant IMC or IMR are significant predictors of recurrent volvulus.17 However, segmental resection may be safer as only 1 study reported a mortality rate.12 Furthermore, it achieved excellent results in some studies,35,36 and thus, more detailed evaluation of this procedure is warranted. It is likely that more careful selection of patients may be associated with improved outcomes as resection has not always been tailored to the extent of the bowel dilatation, with segmental resection being performed in cases where the whole colon and rectum were dilated.12,41 Comprehensive preoperative assessment of anorectal and colonic function to identify those patients with normal function proximal to the dilated bowel may be crucial to the selection of patients for limited resection of the dilated/dysfunctional segment.

Rectal Procedures

The rectum is dilated in the majority of cases of megabowel3,12,38,41 and is functionally abnormal and hypopropulsive.10,11 Therefore, preservation of a dilated, dysfunctional rectum appears illogical and may explain the recurrence of fecal impaction and symptoms.6,12,21,34 Furthermore, anastomosis of a normal diameter colon to a hugely dilated rectum is technically very demanding.44 Consequently, procedures that involve only resection of all or part of the colon seem inappropriate if there is coexisting IMR.45

The overall success rates of the various rectal procedures (± resection of the proximal colon) ranged from 71% to 87%. Proctectomy allows resection of the dilated rectum with formation of a coloanal anastomosis, thus retaining proximal colon and potentially giving superior functional results to those achieved by an ileal pouch. Consequently, it may have a place in the management of patients with dilatation confined to the rectum. More extensive preoperative evaluation of proximal colonic function may identify those patients with dysfunction limited to the distal colon and rectum and improve outcomes following surgery.13,44 However, the mortality of 6% to 14% and serious morbidity secondary to pelvic sepsis and fistulation associated with proctectomy suggests that VRR, which involves less radical pelvic dissection, is a safer alternative in such patients, although results of this procedure are currently only limited to small numbers of patients and with limited follow-up. Long-term studies will determine whether the “reduced rectum” subsequently dilates following VRR.

The Duhamel procedure was initially described in patients with Hirschsprung disease52 and has subsequently been applied to patients with IMR. It involves excision of the dilated rectum and oversewing of the distal rectal stump via an abdominal approach, followed by creation of an end-to-side anastomosis of the proximal bowel to the posterior aspect of the rectal stump via a perineal approach. The overall success rate of the procedure (87%) was the best reported for any procedure. However, the outcome of this procedure was highly variable (50%–98%). Furthermore, it was associated with significant mortality and an unacceptably high morbidity (up to 60%). Complications were frequently serious and usually involved anastomotic problems and pelvic sepsis,33,38,42 with many patients requiring further surgery for complications or persistent constipation.42 Consequently, it cannot be recommended for patients with IMR.

Since dysmotility may affect the entire large bowel, and given that a proportion of patients develop recurrent constipation following resection of all or part of the colon and/or rectum, it may be argued that a restorative panproctocolectomy with ileal pouch formation is a more suitable option in patients with extensive dilatation of the colon and rectum. Based on successful application of this procedure in 2 patients with intractable constipation,53 it was first performed in patients with IMB by Hosie et al40 in 1990. The overall morbidity of the procedure was 9%, although it was as high as 40%.40 It is considered that normal anal sphincter function is a prerequisite for a good functional result, enabling avoidance of fecal incontinence.45 However, it has been suggested that preoperative sphincter dysfunction does not preclude a successful outcome13 since low sphincter pressures may recover following proctocolectomy to give satisfactory functional results.24 Recovery of function in such patients probably reflects the relaxed state of the anal sphincters preoperatively, secondary to chronic elicitation of the rectoanal inhibitory reflex, due to retention of enormous fecalomas in the rectum.24 Preoperative assessment of anal sphincter morphology using endoanal ultrasound to exclude anatomic disruption of the sphincter complex would also be a prudent measure as dysfunction secondary to compromised integrity of the anal sphincters would not be expected to recover following surgery.

Pelvic Floor Procedures

Outlet obstruction is a recognized cause of constipation,54 and considerable emphasis has been placed on a proposed mechanism of failure of relaxation of the pelvic floor musculature and anal sphincters.19 Consequently, division of the puborectalis and internal sphincterotomy have been performed in patients with IMB in an attempt to reduce the tone of these respective muscles in an attempt to normalize bowel function. Most experience of these procedures has been obtained in constipated patients with normal-caliber bowel and outlet obstruction, and a review of the literature reports disappointing success rates of only 48%.39 Despite short-term improvement in up to 60% of patients,54 long-term results of pelvic-floor procedures are disappointing, even as a treatment of short-segment Hirschsprung disease.55 In recent years, the concept of paradoxic contraction of the pelvic-floor musculature as a cause of constipation has been seriously questioned,56–58 and this may explain the lack of therapeutic response, and continued failure of relaxation of the puborectalis, following surgery. Furthermore, there is a risk of incontinence following such procedures.19,59 Consequently, such procedures cannot be recommended for treatment of constipation in patients with IMB.

Fecal Diversion

A stoma offers a less radical alternative to other procedures for IMB and is also potentially reversible. However, stoma formation is associated with change or distortion of body image, which may lead to physical and psychosocial morbidity,60 and is unacceptable to some patients. The results suggest that stomata in patients with megabowel should be created proximal to dysfunctional bowel, as determined using physiologic investigations, or as a minimum, using bowel of normal caliber. Patients should be warned that symptoms of abdominal pain and distension may persist and may be due to underlying “irritable bowel syndrome.”45

Contemporary Management

Patients with functional constipation can be divided on the basis of anorectal and colonic physiologic investigations into those with dysmotility of all or part of the colon and/or outlet obstruction.61 In those patients managed surgically, thorough preoperative evaluation is considered mandatory to guide choice of procedure.48 Traditionally, however, this has rarely been the case in patients with megabowel, where there is little evidence of selection of patients for specific procedures. Indeed, patients with dilatation of the colon and rectum have undergone segmental resection,12,41 for example, and conversely, those with distal dilatation only have undergone subtotal colectomy.41 In recent years, more sophisticated physiologic tests, allowing assessment of colonic transit and motility, have allowed a more directed approach to be taken45,46 and have allowed the formulation of strategies for surgical intervention in patients with IMB, according to the function of bowel proximal to the dilated segment.13

As in patients undergoing surgery for other functional bowel disorders,47 it seems logical that comprehensive physiologic investigation of bowel function, including studies of colonic transit and rectal evacuation, should be performed preoperatively to guide appropriate selection of surgical procedure and to ensure adequate resection of the dilated/dysfunctional bowel and reasonable function of any preserved bowel, as well as being part of the objective comparison between differing interventions. In addition, formal evaluation of proximal enteric function using esophageal and small-bowel manometry may be warranted as a proportion of patients with IMB have evidence of upper gastrointestinal dysmotility.62 However, it remains as yet unclear to which physiologic abnormalities aid selection of patients for different surgical procedures and whether varying pathophysiologies have value in predicting clinical outcome,39 although the presence of upper gastrointestinal dysmotility was associated with a less-favorable outcome following surgery in patients with severe constipation.63

CONCLUSIONS

This systematic review has revealed that the reported outcome data for surgery for IMB must be interpreted with extreme caution, and comparison between studies is problematic due to limitations in study design, failure to adhere to the strict inclusion of subjects with objectively demonstrable bowel dilatation that is idiopathic in nature, and variation in the methods used to acquire outcome data, success rates, functional results, and postoperative morbidity. In particular, data relating to long-term outcome and effects on quality of life are lacking, and studies often only included relatively small numbers of patients. Currently, data to support the selection of surgical procedures on the basis of the extent of the dilatation, or more correctly, the dysfunction of the bowel, are lacking and is an area that warrants further investigation. However, such an approach seems logical and may ultimately be associated with improved outcomes. With this in mind and from the published results of surgery, the following tentative recommendations can be made:

In patients with IMC with a nondilated functional rectum, subtotal colectomy and IRA is the procedure of choice as segmental resection results in higher incidence of postoperative constipation. However, patients must be counseled that this procedure is associated with a definite mortality and a 20% morbidity that frequently requires further surgical intervention and which is most commonly secondary to bowel obstruction.

In patients with dilatation affecting the whole of the colon and rectum (megabowel), the most appropriate procedure appears to be a restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch reconstruction. Success rates appear to be in the region of 70% to 80%, although the procedure is complex and patients should be warned of the risk of suboptimal pouch function, characterized by frequency of defecation and nocturnal fecal soiling.

In patients with only distal dilatation of the bowel (IMR ± megasigmoid), there appears to be very little to choose between VRR and proctectomy with coloanal anastomosis in terms of success rates (70%–80%). However, the mortality associated with proctectomy suggests that VRR, which involves less-radical pelvic dissection, is a safer alternative in such patients, although results of this procedure are currently only limited to small numbers of patients and with limited follow-up.

The Duhamel and endorectal pull-through procedures cannot be recommended because of their variable results and unacceptably high morbidity, with many patients requiring further surgery for complications or persistent constipation. To date, the pelvic-floor procedures evaluated for IMB are completely ineffective.

The final option in patients wishing to avoid the risks of these complex procedures is the creation of a stoma. It also provides an alternative when other procedures have not been successful. However, this should be created proximal to the dilated/dysfunctional bowel, and patients should be warned that it may not address symptoms of abdominal pain and distension.

It is clear that the surgical management of IMB is complex and should be reserved for patients with intractable symptoms with impaired quality of life who have failed or cannot tolerate nonsurgical management. This should preferably be performed in a specialist surgical unit and involve a multidisciplinary approach as patients require comprehensive clinical, psychologic, and physiologic evaluation and frequently have coexisting urologic dysfunction.45 Currently, no form of surgical intervention offers a 100% cure rate, and preoperative counseling before surgery is obligatory so that patients can understand that surgery may only improve rather than cure symptoms, or that in the event of “surgical failure,” they may subsequently require a permanent stoma.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Mr Marc A. Gladman is supported by the Frances and Augustus Newman Foundation Research Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons of England.

Footnotes

Mr Marc A. Gladman is supported by the Frances and Augustus Newman Foundation Research Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons of England.

Reprints: Professor N. S. Williams, Professor of Surgery and Centre Lead Centre for Academic Surgery, 4th Floor Alexandra Wing, The Royal London Hospital, Whitechapel, London E1 1BB, UK. E-mail: n.s.williams@qmul.ac.uk.

REFERENCES

- 1.Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, et al.. U.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders: prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1569–1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halder SL, Locke GR 3rd, Talley NJ, et al. Impact of functional gastrointestinal disorders on health-related quality of life: a population-based case-control study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;19:233–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gattuso JM, Kamm MA. Clinical features of idiopathic megarectum and idiopathic megacolon. Gut. 1997;41:93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Todd I. Discussion on megacolon and megarectum with the emphasis on conditions other than Hirschsprung's disease. Proc R Soc Med. 1961;54:1035–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehrenpreis T. Megacolon and megarectum in older children and young adults: classification and terminology. Proc R Soc Med. 1967;60:799–801. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnes PR, Lennard-Jones JE, Hawley PR, et al. Hirschsprung's disease and idiopathic megacolon in adults and adolescents. Gut. 1986;27:534–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Preston DM, Lennard-Jones JE, Thomas BM. Towards a radiologic definition of idiopathic megacolon. Gastrointest Radiol. 1985;10:167–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verduron A, Devroede G, Bouchoucha M, et al. Megarectum. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:1164–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiarioni G, Bassotti G, Germani U, et al. Idiopathic megarectum in adults: an assessment of manometric and radiologic variables. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:2286–2292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Connell AM. Colonic motility in megacolon. Proc R Soc Med. 1961;54:1040–1043. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gattuso JM, Kamm MA, Morris G, et al. Gastrointestinal transit in patients with idiopathic megarectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:1044–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lane RH, Todd IP. Idiopathic megacolon: a review of 42 cases. Br J Surg. 1977;64:307–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Suilleabhain CB, Anderson JH, McKee RF, et al. Strategy for the surgical management of patients with idiopathic megarectum and megacolon. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1392–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamm MA, Stabile G. Management of idiopathic megarectum and megacolon. Br J Surg. 1991;78:899–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goligher J. Discussion on megacolon and megarectum with the emphasis on conditions other than Hirschsprung's disease. Proc R Soc Med. 1961;54:1053–1055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mimura T, Nicholls T, Storrie JB, et al. Treatment of constipation in adults associated with idiopathic megarectum by behavioural retraining including biofeedback. Colorectal Dis. 2002;4:477–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung YF, Eu KW, Nyam DC, et al. Minimizing recurrence after sigmoid volvulus. Br J Surg. 1999;86:231–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keighley MRB. Adult Hirschsprung's disease, megacolon and megarectum. In: Keighley MRB, Williams NS, eds. Surgery of the Anus, Rectum & Colon. 2nd ed. London: WB Saunders; 1993:639–674. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamm MA, Hawley PR, Lennard-Jones JE. Lateral division of the puborectalis muscle in the management of severe constipation. Br J Surg. 1988;75:661–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vasilevsky CA, Nemer FD, Balcos EG, et al. Is subtotal colectomy a viable option in the management of chronic constipation? Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:679–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshioka K, Keighley MR. Clinical results of colectomy for severe constipation. Br J Surg. 1989;76:600–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dean DL. Surgery for acquired megacolon. Arch Surg. 1966;92:724–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gagliardi G, Hershman MJ, Hawley PR. Idiopathic megarectum treated by Duhamel's operation. J R Soc Med. 1992;85:358–359. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown SR, Shorthouse AJ. Restorative proctocolectomy for idiopathic megarectum: postoperative recovery of hypotonic anal sphincters: report of two cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:625–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenhalgh T, How to Read a Paper: The Basics of Evidence Based Medicine. London: BMJ Publishing Group; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawson JO, Nixon HH. Anal canal pressures in the diagnosis of Hirschsprung's disease. J Pediatr Surg. 1967;2:544–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agachan F, Chen T, Pfeifer J, et al. A constipation scoring system to simplify evaluation and management of constipated patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:681–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaizey CJ, Carapeti E, Cahill JA, et al. Prospective comparison of faecal incontinence grading systems. Gut. 1999;44:77–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watkins GL. Operative treatment of acquired megacolon in adults. Arch Surg. 1966;93:620–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kune GA. Megacolon in adults. Br J Surg. 1966;53:199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jennings PJ. Megarectum and megacolon in adolescents and young adults: results of treatment at St. Mark's Hospital. Proc R Soc Med. 1967;60:805–806. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hughes ES, Hardy KJ, Cuthbertson AM. Megacolon in adults. Dis Colon Rectum. 1969;12:190–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haddad J. Treatment of acquired megacolon by retrorectal lowering of the colon with a perineal colostomy: modified Duhamel operation. Dis Colon Rectum. 1969;12:421–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith B, Grace RH, Todd IP. Organic constipation in adults. Br J Surg. 1977;64:313–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCready RA, Beart RW Jr. The surgical treatment of incapacitating constipation associated with idiopathic megacolon. Mayo Clin Proc. 1979;54:779–783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hughes ES, McDermott FT, Johnson WR, et al. Surgery for constipation. Aust N Z J Surg. 1981;51:144–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Belliveau P, Goldberg SM, Rothenberger DA, et al. Idiopathic acquired megacolon: the value of subtotal colectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1982;25:118–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parc R, Berrod JL, Tussiot J, et al. Megacolon in adults: apropos of 76 cases. Ann Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1984;20:133–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coremans GE. Surgical aspects of severe chronic non-Hirschsprung constipation. Hepatogastroenterology. 1990;37:588–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hosie KB, Kmiot WA, Keighley MR. Constipation: another indication for restorative proctocolectomy. Br J Surg. 1990;77:801–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stabile G, Kamm MA, Hawley PR, et al. Colectomy for idiopathic megarectum and megacolon. Gut. 1991;32:1538–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stabile G, Kamm MA, Hawley PR, et al. Results of the Duhamel operation in the treatment of idiopathic megarectum and megacolon. Br J Surg. 1991;78:661–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stabile G, Kamm MA, Hawley PR, et al. Results of stoma formation for idiopathic megarectum and megacolon. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1992;7:82–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stabile G, Kamm MA, Phillips RK, et al. Partial colectomy and coloanal anastomosis for idiopathic megarectum and megacolon. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:158–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stewart J, Kumar D, Keighley MR. Results of anal or low rectal anastomosis and pouch construction for megarectum and megacolon. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1051–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams NS, Fajobi OA, Lunniss PJ, et al. Vertical reduction rectoplasty: a new treatment for idiopathic megarectum. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1203–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rotholtz NA, Wexner SD. Surgical treatment of constipation and fecal incontinence. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2001;30:131–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pfeifer J, Agachan F, Wexner SD. Surgery for constipation: a review. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:444–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hughes SF, Williams NS. Antegrade enemas for the treatment of severe idiopathic constipation. Br J Surg. 1995;82:567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eccersley AJ, Maw A, Williams NS. Comparative study of two sites of colonic conduit placement in the treatment of constipation due to rectal evacuatory disorders. Br J Surg. 1999;86:647–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stabile G, Kamm MA. Surgery for idiopathic megarectum and megacolon. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1991;6:171–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Duhamel B. Une nouvelle operation pour le megacolon congenital: l'abaissement retro-rectal et trans-anal du colon et son application possible au traitement de quelques autres malformations. Presse Med. 1956;64:2249–2250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nicholls RJ, Kamm MA. Proctocolectomy with restorative ileoanal reservoir for severe idiopathic constipation: report of two cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:968–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martelli H, Devroede G, Arhan P, et al. Mechanisms of idiopathic constipation: outlet obstruction. Gastroenterology. 1978;75:623–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pinho M, Yoshioka K, Keighley MR. Long-term results of anorectal myectomy for chronic constipation. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:795–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schouten WR, Briel JW, Auwerda JJ, et al. Anismus: fact or fiction? Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:1033–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Voderholzer WA, Neuhaus DA, Klauser AG, et al. Paradoxical sphincter contraction is rarely indicative of anismus. Gut. 1997;41:258–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chan CL, Scott SM, Knowles CH, et al. Exaggerated rectal adaptation: another cause of outlet obstruction. Colorectal Dis. 2001;3:141–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lunniss PJ, Gladman MA, Hetzer F, et al. Risk factors in acquired faecal incontinence. J R Soc Med. 2004;97:111–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thomas C, Madden F, Jehu D. Psychological effects of stomas, I: psychosocial morbidity one year after surgery. J Psychosom Res. 1987;31:311–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Diamant NE, Kamm MA, Wald A, et al. AGA technical review on anorectal testing techniques. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:735–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Basilisco G, Velio P, Bianchi PA. Oesophageal manometry in the evaluation of megacolon with onset in adult life. Gut. 1997;40:188–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Redmond JM, Smith GW, Barofsky I, et al. Physiological tests to predict long-term outcome of total abdominal colectomy for intractable constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:748–753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]