Abstract

Junonia coenia densovirus (JcDNV) is an autonomous parvovirus that infects the larvae of the common buckeye butterfly, Junonia coenia. Unlike vertebrate parvoviruses, the genes encoding the structural protein and nonstructural (NS) proteins of JcDNV are in opposite orientations; thus, each strand contains a sense and antisense open reading frame (ORF). The promoter at map position 93 controls expression of NS ORFs 2, 3, and 4, which encode three NS proteins, NS-1, NS-2, and NS-3. These proteins are likely to be involved in viral DNA replication, among other functions. In contrast to the nonstructural proteins of the vertebrate parvoviruses, the NS proteins of the Densovirinae have not been characterized. Here, we describe biochemical properties of the NS-1 protein of JcDNV. The NS-1 ORF was cloned in frame with the Escherichia coli malE gene, which encodes the bacterial maltose binding protein (MBP). Using electrophoretic mobility shift and DNase I protection assays, we identified the region of the JcDNV terminal sequence that is recognized specifically by the MBP-NS-1 fusion protein. The site consists of (GAC)4 and is located on the A-A′ region of the terminal palindrome. In addition, the MBP-NS-1 fusion protein catalyzes the cleavage of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) substrates derived from the JcDNV putative origin of replication, primarily at two sites in the motif 5′-G*TAT*TG-3′. One cleavage site is between the thymidine dinucleotide at positions 92 and 93 and the other site corresponds to thymidine at nucleotide 95; both sites are on the complementary strand of the sequence assigned GenBank accession number A12984. Cleavage of ssDNA is dependent on the presence of a divalent metal cofactor but does not require nucleoside triphosphate hydrolysis. Parvovirus NS proteins contain the phylogenically conserved Walker A- and B-site ATPase motifs. These sites in JcDNV NS-1 diverge from the consensus, yet despite these atypical motifs our analyses support that MBP-NS-1 has ATP-dependent helicase activity. These results indicate that JcDNV NS-1 possesses activities common to the superfamily of rolling-circle replication initiator proteins in general and the parvovirus replication proteins in particular, and they provide a basis for comparative analyses of the structure and function relationships among the parvovirus NS-1 equivalents.

The Parvoviridae consist of two subfamilies: the Parvovirinae, which infect vertebrates, and the Densovirinae, which infect invertebrates. Junonia coenia densovirus (JcDNV) is an autonomously replicating densovirus that infects the larvae of the common buckeye butterfly, Junonia coenia. The JcDNV genome is a single-stranded, linear DNA molecule of approximately 6 kb in length (13, 32). JcDNV genomic organization differs from that of the Parvovirinae in that coding regions occur on both strands of the double-stranded replicative form viral genome (13). On one strand, a single open reading frame (ORF1) encodes four structural proteins, VP1, VP2, VP3, and VP4. On the complementary strand, ORF2, ORF3, and ORF4 encode nonstructural proteins NS-1, NS-2, and NS-3. NS-1, NS-2, and NS-3 are 545, 275, and 232 amino acids in length, respectively. The predicted molecular masses of the proteins encoded by the nonstructural NS-1, NS-2, and NS-3 ORFs are 60, 30, and 28 kDa. ORF1 and ORF2 are regulated by promoters at map positions 9 and 93 (P9 and P93), respectively (Fig. 1A). Similar to adeno-associated virus (AAV) and some of the autonomous parvoviruses (2, 4, 6, 7, 23, 25), an infectious particle of JcDNV may contain either strand of the virus genome, so that in a population of infectious particles half of the virions contain a plus strand and half contain a minus strand. Relatively long terminal repeat (TR) sequences (Fig. 2A) flank the coding sequences. The first 96 nucleotides (nt) of the TR, from either the 5′ or 3′ end of the genome, can fold into a T-shaped hairpin structure similar to those predicted for certain vertebrate parvoviruses (Fig. 2D and E). As a result of the strand transfers and inversions that occur during replication, flip and flop conformations arise (17, 18, 30). This phenomenon is common to the ends of all vertebrate parvoviruses with TRs (1, 5, 31). The presence of terminal palindromic sequences is a common feature for members of the Parvoviridae family, and this element acts as the origin of DNA replication (8, 21). Parvovirus replication initiator proteins possess the following activities: binding to a sequence element within the viral TRs, sequence- and strand-specific nicking activity, and helicase activity. These activities are necessary for efficient virus DNA replication (11, 12, 20, 24, 26, 34).

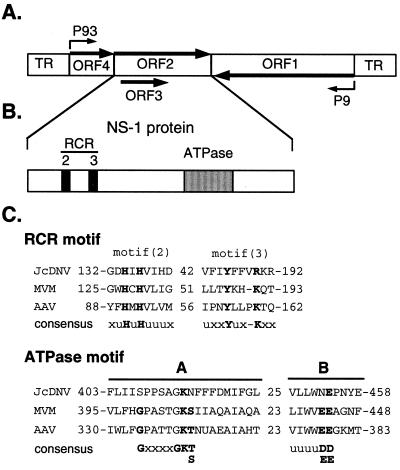

FIG. 1.

(A) Diagrammatic representation of JcDNV genomic organization. The JcDNV genome contains four major open translational reading frames, and both strands of the genome encode polypeptides. The largest is ORF1, which occupies the 5′ half of one strand, whereas ORF2, ORF3, and ORF4 span the 5′ half of the complementary strand. ORF1 encodes four structural polypeptides, VP1, VP2, VP3, and VP4. ORF2, ORF3, and ORF4 encode nonstructural polypeptides NS-1, NS-2, and NS-3. The positions of the two promoters at map positions 9 and 93 are indicated. (B) Schematic representation of the ORF2 gene product, NS-1. NS-1 contains amino acid motifs conserved among RCR initiator proteins as well as motifs associated with ATPase activity. (C) Comparison of the RCR and ATPase motifs of JcDNV NS-1 with minute virus of mice (MVM) NS-1 protein and AAV2 Rep68/78 proteins. The conserved residues are defined as amino acids that are phylogenically retained. u, bulky hydrophobic residue; x, any residue. The Walker A- and B-sites comprise the ATPase motif. In JcDNV NS-1, an asparagine residue substitutes for the conserved threonine or serine residue in the A-site. The B-site in JcDNV NS-1 contains a single acidic residue rather than the two conserved aspartic acid and glutamic acid residues. The so-called invariant amino acid residues are indicated by bold, uppercase letters.

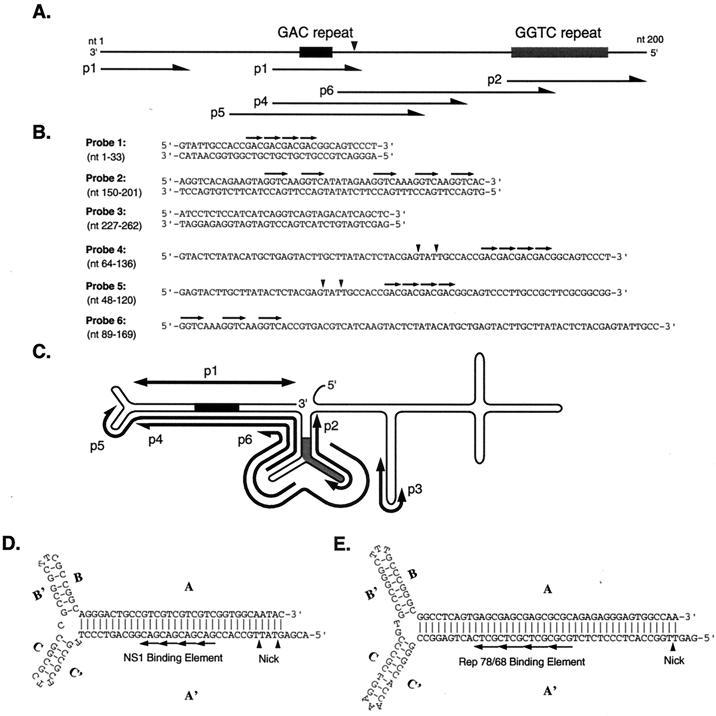

FIG. 2.

Organization of the terminal palindrome and oligodeoxynucleotide probes used in this study. (A) The end of the JcDNV genome is represented with the positions of the GGTC and GAC repeats denoted. The filled triangle is positioned at the nick site. The arrows underneath indicate the positions of the oligonucleotide probes. (B) Sequences of the oligonucleotides used as probes. Short repeats are indicated by overhead arrows. The filled triangles are positioned at the nick sites determined in this study. (C) The extensive terminal palindrome is represented in a potential secondary structural conformation. The positions of the oligonucleotide probes are shown. Bidirectional arrows represent duplex oligonucleotides, while the polarity of single-stranded probes is represented by one-headed arrows. (D and E) Comparison of the structures of origins of replication between JcDNV and AAV2 ori. (D) Possible secondary structure of the extremity of the JcDNV genome providing maximal base pairing. The four horizontal arrows indicate the GAC repeat to which JcDNV NS-1 binds specifically. The filled triangle indicates a possible nicking site. (E) Sequence of the AAV2 ITR folded into a hairpin structure. Again, the arrows and filled triangle indicate the Rep-binding site and nicking site, respectively.

Among the rolling-circle replication (RCR) initiator protein superfamily, three conserved motifs have been identified which are associated with single-strand nicking activities (19). Two of these conserved motifs are readily identifiable in the Parvoviridae nonstructural proteins (Fig. 1C). Inspection of the JcDNV NS-1 sequence reveals that the RCR motifs are located in the amino terminal half of NS-1. Motif 2, uHuHuuu (where u is a hydrophobic amino acid) is located at residues 132 to 140 of JcDNV NS-1. Motif 3, uxxYuxxxK (with x representing any amino acid), contains the active tyrosine involved in nicking activity. Within the carboxy-terminal half of NS-1 are sequences associated with nucleoside triphosphate binding and hydrolysis (Fig. 1C, ATPase motif). The Walker A-site, GxxxxGK(T/S), contains a lysine residue that interacts with a nucleoside triphosphate, typically ATP (33). The B-site, which consists of two acidic residues preceded by four hydrophobic residues, uuuu(D/E)(D/E), is thought to complex with the metal cation cofactor. Thus, sequence analysis of the JcDNV NS-1 protein indicates that NS-1 is a nickase with ATPase activities. In order to confirm these predictions, we investigated the ability of JcDNV NS-1 to function as a nickase and helicase. For this purpose, we cloned the coding region of NS-1 (or ORF2) in frame with the coding sequence of the Escherichia coli malE gene, which encodes the maltose binding protein (MBP). The MBP-NS-1 fusion protein was overexpressed in E. coli and analyzed for biochemical activities. We report here that recombinant NS-1 fusion protein binds specifically to the motif (GAC)4 located within the terminal 96 nt of the TR sequence of the JcDNV genome. The sequence-specific binding activity appears to function independently of DNA secondary structure. The results of nicking activity assays demonstrated that MBP-NS-1 specifically cleaves single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) substrates derived from the predicted JcDNV origin of replication. This nicking activity is dependent on a metal divalent cation cofactor but does not require ATP. In addition, we show here that MBP-NS-1 possesses helicase activity as judged by its ability to unwind partial duplex DNA substrates. The helicase activity is strictly dependent upon the presence of both ATP and metal divalent cation cofactors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

NS-1 cloning.

The NS-1 coding sequence (nt 4662 to 3021 of the JcDNV genome) was amplified by PCR with Pfu polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), as specified by the manufacturer, with the following primer pair: 5′-ACGGATCCCAGATGAAGAATGGAGACACCAAC-3′ and 5′-GCAAGCTTAAATGTAATATTATATTTACTC-3′. The cycling conditions were 95°C for 45 s, 55°C for 45 s, and 75°C for 2 min for 30 rounds. Following the PCR, the amplified product was digested with BamHI and HindIII and ligated into the BamHI and HindIII sites of pMAL-c2 in frame with the malE ORF (New England Biolabs, Inc., Beverly, Mass.). Constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Mutagenesis.

Lysine residue 413 was specifically mutated to histidine using a QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and the mutation was confirmed by DNA sequencing. The primers for producing the K413H mutation were 5′-CTCCTCCAAGTGCTGGTCACAATTTCTTTTTTGATATGATC-3′ and 5′-GATCATATCAAAAAAGAAATTGTGACCAGCACTTGGAGGAG-3′. Base changes relative to the wild-type NS-1 sequence are underlined. The resulting protein product was designated MBP-NS-1-NTP. Construction and characterization of the AAV type 2 (AAV2) MBP-Rep78 fusion protein has been described elsewhere (10, 29).

Protein purification.

MBP fusion proteins were expressed and purified by amylose affinity chromatography as described previously (10). The largest, presumably full-length MBP-NS-1 protein was further purified by ion-exchange chromatography. The peak fractions eluted from the amylose column were applied to a Q Sepharose HP column and eluted with a 0 to 0.5 M NaCl gradient. Full-length MBP-NS-1 eluted as a single peak at 0.27 to 0.31 M NaCl (data not shown). MBP-NS-1 was greater than 90% homogenous as determined by densitometric analysis of sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 3). Protein concentrations were determined with the Bio-Rad colorimetric assay reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.).

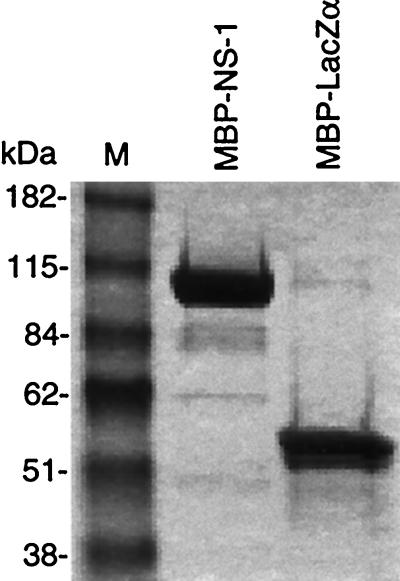

FIG. 3.

Coomassie blue-stained sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel of recombinant fusion proteins. Approximately 10 μg of each protein sample was fractionated on the gel. MBP-NS-1 was purified as described in Materials and Methods. Following affinity and ion-exchange chromatography, MBP-NS-1 and MBP-LacZα were determined to be greater than 90% homogeneous.

Substrates for electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and nicking assay.

Synthetic oligonucleotides were purified by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc., Coralville, Iowa). The substrates and sequences are depicted in Fig. 2A and B. Radiolabeled probes were prepared by 5′-end labeling with [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase as previously reported (10, 28, 29).

EMSA and DNase I protection analysis.

DNA-protein complexes were detected by their reduced mobility on nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels. The assays were performed as previously described (10, 11, 29). Briefly, 2 × 104 cpm of labeled probes (approximately 9 fmol) were incubated with 0.5 μg of MBP fusion proteins (approximately 5 pmol) in 20 μl at room temperature for 30 min. The reaction mixture contained 25 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM KCl, 6.25 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, and 0.5 mM dithiothreitol. Competition experiments included the addition of unlabeled oligonucleotides at the relative concentrations indicated in the figure legends. The sites of protein-DNA interaction were determined by DNase I protection (footprint) analysis. The reactions were performed using the Core Footprinting System (Promega, Madison, Wis.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The footprint substrate consisted of the annealed, duplex oligonucleotides shown in Fig. 2B. DNA sequence ladders were produced by the method of Maxam and Gilbert (22).

Helicase assays and immunodepletion experiments.

The helicase assay was performed as described previously (11, 20, 28). Recombinant proteins were added as indicated in the figure legends. Prior to the in vitro helicase assays, recombinant protein G-agarose beads (GIBCO BRL, Rockville, Md.) were washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline and resuspended in helicase buffer to form a 50% (vol/vol) slurry. Two microliters of rabbit polyclonal anti-MBP serum (New England Biolabs) or anti-SY serum (not specific for MBP recognition; a gift from S. Yang, National Institutes of Health) was incubated for 30 min at 4°C with 0.5 μg of either purified MBP-NS-1, MBP-Rep78, or MBP-LacZ in 20 μl of helicase buffer. Following brief centrifugation, the supernatants were placed into new tubes containing 20 μl of agarose beads and incubated for an additional 30 min at 4°C. Following the incubation and brief centrifugation, the supernatants were transferred to new tubes and incubated with the helicase substrate. The reaction mixtures were then processed as described above for the helicase reactions.

Nickase assay.

The nicking reactions were performed essentially as described previously (11, 20, 27). Briefly, labeled substrates (probes 4 and 5) were separately incubated with protein aliquots at 37°C for 1 h with cleavage reaction buffer containing 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.4), 5 mM MnCl2, 12.5 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 0.1 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml, and 1 mM dithiothreitol. The positions of the cleavage sites were estimated by comparison of the endonuclease products to a purine-specific sequencing reaction of the labeled probe (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.).

RESULTS

The NS-1 protein of JcDNV binds to DNA sequences containing the motif (GAC)4.

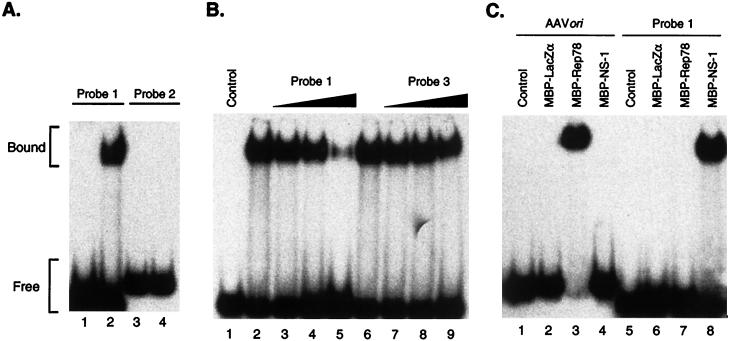

The 517-nt TRs of the JcDNV genome have the potential of forming complex structures; one such structure involves 12 stems and 8 loops (Fig. 2C). The complexity of the structure results from the numerous inverted repeats and interrupted palindromic sequences in this region of the virus genome. Included in this structure are the terminal T-shaped hairpins characteristic of many Parvoviridae genomes (Fig. 2D and E) (1, 2, 9). Both loops at the ends of the cross arms consist of TTC (or the complementary GAA sequence) (Fig. 2D) (13). A parvovirus DNA origin of replication may be defined as the sequence within the terminal palindrome consisting of the binding site and properly positioned nicking site specifically recognized by the virus initiator protein (Fig. 2E). To determine whether JcDNV NS-1 can specifically bind to the JcDNV genome as a putative initiator protein, MBP-NS-1 fusion protein was tested for the ability to bind synthetic oligonucleotide substrates (Fig. 2B). Gel retardation assays (EMSAs) were performed using different duplex oligonucleotide probes. By extrapolation of the binding characteristics of known parvovirus nonstructural proteins, it seemed reasonable that the JcDNV replication initiator protein would recognize a similar motif at the appropriate position within the terminal palindrome to function as an ori. Within the JcDNV TR, trinucleotide and tetranucleotide repeats are present. Probe 1 (Fig. 2B) contains four consecutive trinucleotide repeats of GAC. The motif (GAC)4 is located in the T-shaped terminal hairpin structure generated by the 96 nt at the extremity of the JcDNV genome (Fig. 2A, C, and D). Probe 2 (Fig. 2B) contains a tetrameric, nonconsecutive repeat which is present between nt 151 and 246 in the left hand (or nt 5796 and 5847 in the right hand) of the JcDNV genome (shown schematically in Fig. 2A and C). Incubation of MBP-NS-1 with probe 1 generated a band of lower mobility than probe alone (Fig. 4A). Incubation of MBP-NS-1 with probe 2 did not produce a protein-DNA complex, indicating that there is some level of sequence recognition in the interaction. Figure 4B represents a competition experiment using radiolabeled probe 1 and either unlabeled probe 1 or unlabeled probe 3 as cold competitors. Probe 3 corresponds to nt 5735 to 5770 of the JcDNV genome (Fig. 2A, B, and C) and was used as a nonspecific oligonucleotide control for EMSA. As the concentration of unlabeled probe 1 increased, the amount of bound probe 1 decreased (Fig. 4B, lanes 3, 4, and 5), whereas increasing amounts of a cold competitor, probe 3, had little effect on the bound complex (Fig. 4B, lanes 7, 8, and 9). As an additional control, MBP-NS-1 or MBP-Rep78 was incubated with either probe 1 or a probe corresponding to the AAV2 ori (Fig. 4C). As shown in lanes 3 and 7 of Fig. 4C, MBP-Rep78 formed a complex only with the AAV ori probe. Lanes 4 and 8 show MBP-NS-1 complexed only with probe 1. Incubation of either substrate with MBP-β-galactosidase fusion protein (MBP-LacZα) (Fig. 4C, lanes 2 and 6) produced no protein-DNA product, providing additional control conditions for nonspecific interactions between the MBP moiety and DNA substrate as well for bacterial proteins that may copurify with MBP fusion proteins. These findings are supportive of specific protein-DNA interactions.

FIG. 4.

EMSA results. Specificity of NS-1 was determined by EMSA using substrates derived from different regions of the JcDNV genome (probes 1, 2, and 3) or the AAV2 ITR. Each 20 μl of reaction mixture contained 20,000 cpm of 32P-radiolabeled probe (approximately 9 fmol) and 0.5 μg of fusion protein (approximately 5 pmol). (A) NS-1 protein of JcDNV binds to DNA sequences containing the motif (GAC)4. Incubation of MBP-NS-1 with probe 1 (nt 1 to 33) generated a band of lower mobility (lane 2) than did probe alone (lane 1). Probe 2 (nt 150 to 201) contains GGTC repeats (lane 3) and did not produce a protein-DNA complex when incubated with NS-1 (lane 4). (B) Binding competition between radiolabeled probe 1 and increasing amounts of unlabeled oligonucleotide probe 1 (nt 1 to 33) or probe 3 (nt 227 to 262). Lane 1, probe 1 only; lanes 2 and 6, NS-1 with no competitor; lanes 3, 4, and 5, NS-1 with 90, 180, and 900 fmol of unlabeled probe 1 (10-, 20-, and 100-fold excess, respectively). Unlabeled probe 3 (nt 227 to 262) had a limited effect on MBP-NS-1-probe 1 interaction. Lanes 7, 8, and 9, MBP-NS-1 with 90, 180, or 900 fmol of unlabeled probe 1 (10-, 20-, and 100-fold excess, respectively). (C) Oligonucleotide probe derived from the AAV2 ITR (AAV ori) is recognized specifically by Rep78 (lane 3) but not by NS-1 (lane 4). JcDNV ITR sequences (probe 1) are recognized specifically by NS-1 (lane 8) but not by Rep78 (lane 7). Lanes 1 to 4, AAV ori probe with no added protein (lane 1), MBP-LacZα (lane 2), MBP-Rep78 (lane 3), or MBP-NS-1 (lane 4). Lanes 5 to 8, JcDNV probe 1 with no added protein (lane 5), MBP-LacZα (lane 6), MBP-Rep78 (lane 7), or MBP-NS-1 (lane 8).

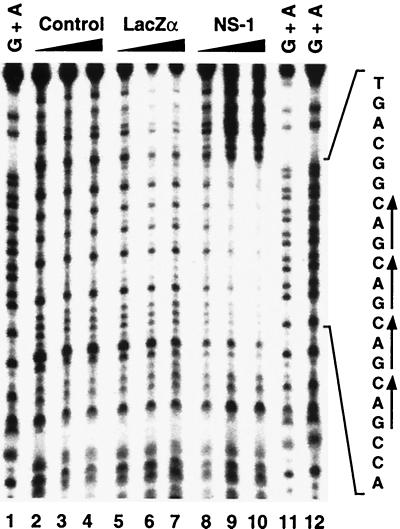

DNase I protection.

Since stable interactions occurred between NS-1 and DNA probe 1, it should be possible to determine which sequences within the terminal repeat are involved in the binding interaction. Protection from DNase I digestion (footprinting) was used with a duplex, radiolabeled probe slightly longer than probe 1 (described in Materials and Methods). Either MBP-LacZα or MPB-NS-1 was incubated with the probe and the mixtures were treated with DNase I for 60, 90, and 120 s (Fig. 5). The products were fractionated electrophoretically on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel and a purine-specific chemical sequencing reaction of the same oligonucleotides was included for size standards. With increasing time of DNase I treatment, the bands within the region encompassing the GAC repeat become fainter as the bands flanking this region were intensified (Fig. 5, lanes 8, 9, and 10). MBP-LacZα did not protect the probe from DNase I digestion (Fig. 5, lanes 5, 6, and 7), similar to the results with the no-added-protein control (lanes 2, 3, and 4).

FIG. 5.

DNase I footprinting with MBP-NS-1. Probe 5 (nt 48 to 120) (Fig. 2) containing GAC repeat was annealed to an unlabeled complementary oligonucleotide and incubated with 10 μg of MBP-NS-1 followed by incubation for 60, 90, or 120 s with DNase I (lanes 8 to 10). As a control, the duplex substrate was mock incubated (lanes 2 to 4) or incubated with 10 μg of MBP-LacZα (lanes 5 to 7) prior to DNase I digestion. Lanes 1, 11, and 12 are G+A ladders produced by purine-specific chemical cleavage reaction. The protected region encompassing the GAC repeat is labeled on the left side of the autoradiograph.

Strand- and site-specific nicking activity of NS-1 on the JcDNV inverted TR (ITR).

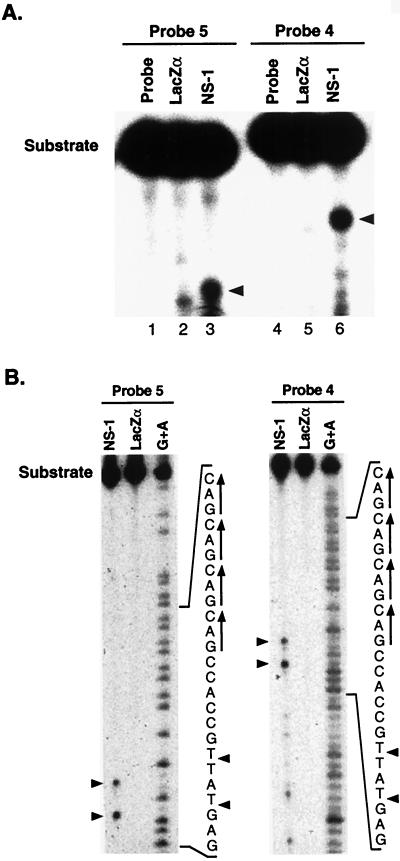

If both JcDNV NS-1 and vertebrate parvovirus nonstructural proteins perform analogous roles in DNA replication, then a vital step in this process is nicking DNA at a defined site. Characterization of the nicking activities of MBP-NS-1 was tested by using an in vitro nicking assay with oligonucleotide substrates corresponding to the JcDNV TR. MBP-NS-1 was incubated with JcDNV TR single-stranded oligonucleotide substrates (Fig. 2B, probes 4 and 5). A major cleavage product, as well as minor products, was produced with either probe 4 or probe 5 (Fig. 6A). In contrast, no major cleavage products were detected with MBP-LacZα with either probe 4 or probe 5. MBP-NS-1 cleavage of DNA was detected on the strand containing GAC repeats but not on the complementary strand (data not shown). To determine more accurately the nicking site, the cleavage reactions were resolved on a sequencing gel. The sites of cleavage were approximated by comparison with a purine-specific chemical sequencing reaction (Fig. 6B) with either probe 5 (left panel) or probe 4 (right panel). Incubation of NS-1 with either probe produced two major cleavage products corresponding to cleavage at thymidines (nt 95 and 92) within the motif 5′-G*TAT*TG-3′. The nucleotide numbering refers to the complementary strand of the sequence characterized in GenBank under accession number A12984. Cleavage of two probes at the same sites confirmed the specificity of the reaction. Thymidine 95 is 1 nt from the end of the JcDNV genome (or complementary end of the genome) and may represent the nick site of NS-1 in vivo. The product produced by cleavage between the thymidine dinucleotide at positions 92 and 93 may be an artifact resulting from the use of synthetic oligonucleotide probes for substrates in the nicking assay.

FIG. 6.

MBP-NS-1 fusion protein specifically cleaves a single-stranded JcDNV ori. (A) Results of nicking assays performed as described in Materials and Methods. The positions of both the substrate and the cleavage products are indicated by arrows. 5′-end-labeled, single-stranded JcDNV ori substrate, probe 4 (nt 64 to 136) or probe 5 (nt 48 to 120) (73-mer; Fig. 2) was incubated without protein (lanes 1 and 4) or with 1.6 μg of MBP-LacZα (lanes 2 and 5) or 1.6 μg of MBP-NS-1 (lanes 3 and 6). The reactions were terminated by the addition of EDTA, and mixtures were heated to 100°C prior to electrophoresis on a denaturing 6% polyacrylamide-Tris-borate-EDTA gel. (B) Mapping of JcDNV ori. 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probe 4 or 5 was incubated with either recombinant MBP-NS-1 or MBP-LacZα and probe alone, respectively. The sizes of the cleavage products were determined by comparison to the products of a purine-specific sequencing reaction of the labeled probe. The sequence of the labeled oligonucleotide probe is shown in the left panel. The NS-1 cleavage sites are indicated by an arrow.

MBP-NS-1 DNA helicase activity.

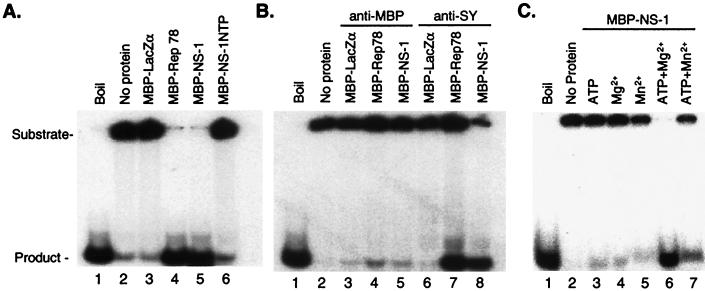

The deduced amino acid sequence of NS-1 indicates the presence of motifs associated with helicase and ATPase activities (Fig. 1C). To determine whether NS-1 can function as a helicase, MBP-NS-1 fusion protein was tested for the ability to unwind a partial duplex substrate. A 5′-32P-end-labeled oligonucleotide annealed to single-stranded M13 DNA was used as a helicase substrate. The MBP-Rep78 fusion protein was employed as a positive control, since this protein has been shown to possess helicase activity (10, 28). Lysine 413, which is within the conserved Walker A-site, has been changed to histidine in the fusion protein MBP-NS-1-NTP. An additional negative control was provided by the MBP-LacZα fusion protein. As shown in Fig. 7A, MBP-NS-1-NTP (lane 6) lacked helicase activity, yielding background levels similar to those of MBP-LacZα and no-added-protein controls (compare lane 6 with lanes 2 and 3). In contrast, incubation of the MBP-NS-1 fusion protein with the partial duplex substrate resulted in a substantial amount of detectable helicase activity that was comparable to the level obtained with MPB-Rep78 (Fig. 7A, lanes 4 and 5). To further ensure that helicase activity associated with purified MBP-NS-1 was not due to contamination with a copurifying bacterial enzyme, immunodepletion experiments were performed with MBP fusion proteins. In these assays, MBP fusion proteins were incubated with either anti-MBP antiserum or, as a control, anti-SY antiserum and precipitated with protein G-agarose beads. Helicase activity was reduced considerably following preincubation of MBP-Rep78 or MBP-NS-1 with the anti-MBP antiserum, as demonstrated by the reduction in the amount of product obtained (Fig. 7B, lanes 4 and 5). In contrast, incubation of MBP fusion proteins with anti-SY antiserum had little effect on the level of helicase activity associated with MBP-Rep78 and MBP-NS-1 (Fig. 7B, lanes 7 and 8, respectively).

FIG. 7.

Helicase assay. The recombinant MBP-NS-1 fusion protein was tested for the ability to displace a radiolabeled oligonucleotide annealed to a circular, single-stranded DNA template (see Materials and Methods). The position of the substrate and the free oligonucleotide product are indicated. The oligonucleotide was heat denatured in lanes labeled “Boil.” Lanes labeled “No protein” are reaction mixtures with no added protein. (A) Results when the reaction mixture received either no fusion protein (lanes 1 and 2) or 0.5 μg of the affinity-purified fusion proteins MBP- LacZα, -Rep78, or -NS-1 and -NS-1-NTP (lanes 3, 4, 5, and 6). (B) Immunodepletion of MBP fusion proteins with anti-MBP rabbit serum abrogated the helicase activity of both MBP-NS-1 and MBP-Rep78 (lanes 4 and 5); in contrast, MBP-NS-1 and MBP-Rep78 retained helicase activity following incubation with nonspecific anti-rabbit serum (lanes 7 and 8). (C) MBP-NS-1 helicase activity requires a metal cation and ATP. Helicase assays were performed with no fusion protein (lanes 1 and 2) or 0.5 μg of MBP-NS-1 fusion protein (lanes 3 to 7) in the presence or absence of Mg2+ or Mn2+ or ATP.

Cofactors for helicase activity.

The dependence of MBP-NS-1 helicase activity on the presence of ATP, Mg2+, or Mn2+ was tested. As seen in Fig. 7C, incubation of MBP-NS-1 with helicase substrate in the presence of ATP but without Mg2+ or Mn2+ resulted in low levels of helicase activity (lane 3). Similarly, the addition of Mg2+ or Mn2+ without ATP resulted in limited helicase activity (lanes 4 and 5). When both ATP and Mg2+ or Mn2+ were included, helicase activity was readily observed (lane 6 and 7). The level of helicase activity observed with ATP plus Mn2+ appeared to be less than that for ATP plus Mg2+. Taken together, these results indicate that MBP-NS-1 possesses DNA helicase activity in the presence of ATP and Mg2+ or Mn2+.

DISCUSSION

The similarity of the terminal structures of JcDNV and AAV suggests that the JcDNV genome replicates in a manner common to the Parvovirinae, even though the terminal sequences are dissimilar and the nonstructural proteins are highly divergent. Since Parvoviridae, as a class, are thought to replicate via a modified rolling circle mechanism, termed a “rolling hairpin” (31), this feature would likely be conserved with the Densovirinae. Therefore, the activities of Densovirinae nonstructural proteins would be expected to include a set of activities that overlap the Parvovirinae nonstructural proteins.

We report here that the JcDNV NS-1 protein recognizes a triplet repeat GAC rather than the tetranucleotide GCTC repeat recognized by the AAV2 p5 Rep proteins. However, the position of the NS-1 binding site within the terminal palindrome, relative to the ends of the genome, is similar to the AAV2 Rep protein binding sites. Using synthetic oligonucleotide substrates, the JcDNV NS-1 major cleavage sites (5′-G*TA*TTG-3′) are dissimilar to the AAV2 (5′-AGT*TGG-3′) and AAV5 (5′-GTG*TGG-3′) nicking sites. Cleavage at thymidines is conserved between NS-1 and AAV Rep proteins. In addition, for both AAV and JcDNV the cleavage sites are separated from the duplex DNA binding site.

As shown in Fig. 6A and B, nicking activity using single-stranded ori substrates produced two major products apparently corresponding to cleavage 5′ of thymidines. One product was generated by cleavage at thymidine 95, which is 1 nt from the end of the virus genome (or complement of the genome sequence). We did not detect cleavage of duplex DNA substrates with MBP-NS-1 (data not shown). This finding is consistent with results with recombinant Rep68 and Rep78, which have greater levels of nicking activity on single-stranded substrates than with duplex substrates. Thus, MBP-NS-1 nicking activity appears to conserve some of the elements of the AAV2 p5 Rep proteins, since both proteins are likely to cleave DNA through a tyrosine-thymidine phosphodiester intermediate and bind to the DNA at a recognition sequence that does not contain the cleavage site.

Nucleoside triphosphate binding sites are present in enzymes from widely divergent organisms, including eubacteria, fungi, insects, and vertebrates, as well as several virus families. All known helicase enzymes possess the so-called Walker A- and B-sites (14, 15). The A-site consists of GxxxxGK(T/S) and the B-site, which follows a variable spacer region, consists of uuuu(D/E)(D/E), where u is a hydrophobic residue. These motifs are among the signatures of the helicase superfamily, and the specific residues within the A- and B-sites are invariant among known helicases (14, 15). Interestingly, the deduced NS-1 protein sequences from five different densovirus genomes deviate from the Walker A- and B-sites. Densovirus isolated from the insect hosts Periplaneta fuliginosa, Diatraea saccharalis, Galleria mellonella, and J. coenia (13, 16; see also GenBank accession numbers AF036333 [D. saccharalis] and L32896 [G. mellonella]) each contain the following residues at the putative Walker A- and B-sites: SxxxxGKNfff-x31-vllwnEp. The deduced NS-1 protein from Bombyx mori (3; GenBank accession number AB042597) differs slightly, with two acidic residues in the B-site: SxxxxGKnffi-x31-vnywDE. The residues in uppercase italics represent conserved positions among the Densovirinae but differ from those in the Walker A- and B-sites. The uppercase bold residues are so-called invariant residues from the A- and B-sites. Thus, it appears as if the A- and B-site homologues among the densovirus NS-1 proteins differ from the universally conserved helicase superfamily motifs. The alternative is that these NS-1 proteins lack helicase activity. The data presented here support the conclusion that the JcDNV NS-1 protein is an ATP-dependent DNA helicase, based on the following empirical results. First, the immunodepletion results strongly suggest that the observed helicase activity is associated with the MBP-NS-1 fusion protein. Second, substitution of the conserved lysine to a histidine abrogated the helicase activity associated with the MBP-NS-1 protein. Last, in the absence of ATP, little or no helicase activity was detected.

Despite the atypical Walker A-site, these results demonstrate that NS-1 is an ATP-dependent DNA helicase. This divergence, unique to the Densovirinae nonstructural proteins, raises some interesting issues regarding the biochemistry of ATPase proteins.

A teleological argument supports the notion that the Densovirinae NS-1 proteins have helicase activity. This activity is likely to be required for replication as well as packaging of the virus genomes into capsids. The nicking activity is conserved among the RCR family of initiator proteins, and the two motifs recognizable in the Parvoviridae are apparent in NS-1, as a nicking activity has been demonstrated. However, the active tyrosine residue has not been identified.

Further studies on the mechanisms of JcDNV replication may provide information of importance to the understanding of Parvoviridae biology and replication initiator proteins in general. By elucidating the details concerning this divergent representative of the Parvoviridae, our understanding of the relationship between structure and function of parvovirus initiator proteins may be expanded. The NS-1 protein displayed biochemical activities comparable to those of other parvovirus initiator proteins, including sequence-specific binding, strand- and site-specific endonuclease activity, and helicase activity. The ability of NS-1 to bind to the viral ITR is an essential function for the viability of the virus. The JcDNV genome has identical terminal palindromes which are capable of forming the characteristic Y-shaped hairpin structure. The JcDNV terminal sequences differ from the vertebrate parvovirus terminal sequence in sequence, size, and structure (3; see also GenBank accession number AB042597). Gel retardation assays demonstrated that the MBP-NS-1 fusion protein exhibits specific binding to the duplex DNA located in the stem region of the Y-shaped hairpin structure and not to other palindromes extruded from the extensive terminal palindrome structure. A specific binding sequence repeat motif, GAC, was identified by DNase I protection analysis. These results indicate that NS-1 DNA binding functions are not limited to recognition of the hairpin structure of the viral ITR but also involve recognition of the specific sequences within this structure.

Acknowledgments

We thank Richard Smith, Sandra Afione, and Michael Schmidt for sharing unpublished observations, helpful technical advice, and critical discussions. Brian Safer provided helpful suggestions for the DNase protection assays.

REFERENCES

- 1.Astell, C. R. 1990. Terminal hairpins of parvovirus genomes and their role in replication, p. 59–79. In P. Tijssen (ed.), CRC handbook of parvoviruses. CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, Fla.

- 2.Bando, H., H. Choi, Y. Ito, and S. Kawase. 1990. Terminal structure of a Densovirus implies a hairpin transfer replication which is similar to the model for AAV. Virology 179:57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bando, H., J. Kusuda, T. Gojobori, T. Maruyama, and S. Kawase. 1987. Organization and nucleotide sequence of a densovirus genome imply a host-dependent evolution of the parvoviruses. J. Virol. 61:553–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bates, R. C., C. E. Snyder, P. T. Banerjee, and S. Mitra. 1984. Autonomous parvovirus LuIII encapsidates equal amounts of plus and minus DNA strands. J. Virol. 49:319–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berns, K. I. 1996. Parvoviridae: the viruses and their replication, p. 2173–2197. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, R. M. Chanock, J. L. Melnick, T. P. Monath, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Virology, 3rd ed., vol. 2. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 6.Berns, K. I., and S. Adler. 1972. Separation of two types of adeno-associated virus particles containing complementary polynucleotide chains. J. Virol. 9:394–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berns, K. I., and J. A. Rose. 1970. Evidence for a single-stranded adenovirus-associated virus genome: isolation and separation of complementary single strands. J. Virol. 5:693–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bohenzky, R. A., R. B. LeFebvre, and K. I. Berns. 1988. Sequence and symmetry requirements within the internal palindromic sequences of the adeno-associated virus terminal repeat. Virology 166:316–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiorini, J. A., F. Kim, L. Yang, and R. M. Kotin. 1999. Cloning and characterization of adeno-associated virus type 5. J. Virol. 73:1309–1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiorini, J. A., M. D. Weitzman, R. A. Owens, E. Urcelay, B. Safer, and R. M. Kotin. 1994. Biologically active Rep proteins of adeno-associated virus type 2 produced as fusion proteins in Escherichia coli. J. Virol. 68:797–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiorini, J. A., S. M. Wiener, R. A. Owens, S. R. Kyostio, R. M. Kotin, and B. Safer. 1994. Sequence requirements for stable binding and function of Rep68 on the adeno-associated virus type 2 inverted terminal repeats. J. Virol. 68:7448–7457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cotmore, S. F., J. Christensen, J. P. Nuesch, and P. Tattersall. 1995. The NS1 polypeptide of the murine parvovirus minute virus of mice binds to DNA sequences containing the motif [ACCA]2–3. J. Virol. 69:1652–1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dumas, B., M. Jourdan, A. M. Pascaud, and M. Bergoin. 1992. Complete nucleotide sequence of the cloned infectious genome of Junonia coenia densovirus reveals an organization unique among parvoviruses. Virology 191:202–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gorbalenya, A. E., and E. V. Koonin. 1989. Viral proteins containing the purine NTP-binding sequence pattern. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:8413–8440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorbalenya, A. E., E. V. Koonin, A. P. Donchenko, and V. M. Blinov. 1989. Two related superfamilies of putative helicases involved in replication, recombination, repair and expression of DNA and RNA genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:4713–4730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo, H., J. Zhang, and Y. Hu. 2000. Complete sequence and organization of Periplaneta fuliginosa densovirus genome. Acta Virol. 44:315–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hauswirth, W. W., and K. I. Berns. 1979. Adeno-associated virus DNA replication: nonunit-length molecules. Virology 93:57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hauswirth, W. W., and K. I. Berns. 1977. Origin and termination of adeno-associated virus DNA replication. Virology 78:488–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ilyina, T. V., and E. V. Koonin. 1992. Conserved sequence motifs in the initiator proteins for rolling circle DNA replication encoded by diverse replicons from eubacteria, eucaryotes and archaebacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:3279–3285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Im, D. S., and N. Muzyczka. 1990. The AAV origin binding protein Rep68 is an ATP-dependent site-specific endonuclease with DNA helicase activity. Cell 61:447–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LeFebvre, R. B., and K. I. Berns. 1984. Unique events in parvovirus replication. Microbiol. Sci. 1:163–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maxam, A. M., and W. Gilbert. 1980. Sequencing end-labeled DNA with base-specific cleavages. Methods Enzymol. 65:499–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayor, H. D., K. Torikai, J. L. Melnick, and M. Mandel. 1969. Plus and minus single-stranded DNA separately encapsidated in adeno-associated satellite virions. Science 166:1280–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nüesch, J. P., S. F. Cotmore, and P. Tattersall. 1995. Sequence motifs in the replicator protein of parvovirus MVM essential for nicking and covalent attachment to the viral origin: identification of the linking tyrosine. Virology 209:122–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rose, J. A., K. I. Berns, M. D. Hoggan, and F. J. Koczot. 1969. Evidence for a single-stranded adenovirus-associated virus genome: formation of a DNA density hybrid on release of viral DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 64:863–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryan, J. H., S. Zolotukhin, and N. Muzyczka. 1996. Sequence requirements for binding of Rep68 to the adeno-associated virus terminal repeats. J. Virol. 70:1542–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith, R. H., and R. M. Kotin. 2000. An adeno-associated virus (AAV) initiator protein, Rep78, catalyzes the cleavage and ligation of single-stranded AAV ori DNA. J. Virol. 74:3122–3129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith, R. H., and R. M. Kotin. 1998. The Rep52 gene product of adeno-associated virus is a DNA helicase with 3′-to-5′ polarity. J. Virol. 72:4874–4881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith, R. H., A. J. Spano, and R. M. Kotin. 1997. The Rep78 gene product of adeno-associated virus (AAV) self-associates to form a hexameric complex in the presence of AAV ori sequences. J. Virol. 71:4461–4471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Straus, S. E., E. D. Sebring, and J. A. Rose. 1976. Concatemers of alternating plus and minus strands are intermediates in adenovirus-associated virus DNA synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 73:742–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tattersall, P., and D. C. Ward. 1976. Rolling hairpin model for replication of parvovirus and linear chromosomal DNA. Nature 263:106–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tijssen, P., and M. Bergoin. 1995. Densonucleosis viruses consititute an increasingly diversified subfamily among parvoviruses. Semin. Virol. 6:347–355. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walker, J. E., M. Saraste, M. J. Runswick, and N. J. Gay. 1982. Distantly related sequences in the alpha- and beta-subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP-requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1:945–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson, G. M., H. K. Jindal, D. E. Yeung, W. Chen, and C. R. Astell. 1991. Expression of minute virus of mice major nonstructural protein in insect cells: purification and identification of ATPase and helicase activities. Virology 185:90–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]