Abstract

Objective:

Fissures, fistulas, abscesses, and anal canal stenosis are manifestations of perianal Crohn disease (CD). There are no known predictors of which patients will fail sphincter-sparing surgical therapy and ultimately require fecal diversion.

Methods:

Of 356 consecutive patients with CD, 24% (86) had perianal CD (age range, 14–83 years), and women were slightly more frequently affected. Clinical variables were examined for factors predictive of the need for permanent fecal diversion.

Results:

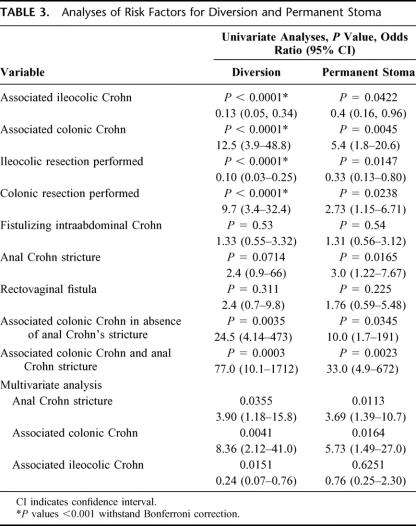

CD associated with perianal CD was limited to the small bowel and/or ileocolic area in 23% of patients; the remainder had colorectal CD. Eighty-six patients underwent 344 operations. Forty-two patients (49%) ultimately required permanent diversion; among them were 21 of 32 patients (66%) with anal stricture and 12 of 20women (60%) with rectovaginal fistula. Univariate analyses of clinical variables were performed with respect to need for permanent fecal diversion. Significant univariate predictors were the presence of colonic CD (P = 0.0045, odds ratio [OR] 5.4), avoidance of ileocolic resection (P = 0.0147, OR 0.4), and the presence of an anal stricture (P = 0.0165, OR 3.0). In multivariate logistic regression, the presence of colonic disease and anal canal stricture were predictors of permanent diversion. The OR associated with the risk of permanent diversion in the presence of colonic disease and in the absence of anal stricture was 10 (P = 0.0345). In the presence of both colonic disease and anal canal stenosis, the OR associated with permanent stoma was 33 (P = 0.0023).

Conclusions:

The management of perianal CD continues to be challenging. Roughly half of patients required permanent fecal diversion, which was even more frequently true for patients with colonic CD and anal stenosis. Recognizing these tendencies will assist both patients and surgeons in planning optimal treatment.

Clinical data of 86 patients with perianal Crohn disease are reviewed with respect to factors predictive of the need for permanent fecal diversion. Forty-two patients (49%) required permanent stoma. Both anal canal stenosis and colonic disease were predictors of the need for fecal diversion, and the combination of both of these increased the likelihood of permanent stoma by over 30-fold.

The frequency of Crohn disease in the United States continues to increase. Despite the availability of newer immunomodulating therapies, surgeons will still frequently be consulted regarding this clinical problem. While immunomodulating therapies often deal well with the inflammatory component of this difficult disease, the scar and fibrosis often seen with anal perianal disease and septic complications associated with fistulizing disease frequently do not respond well to such treatment and often require surgical intervention. Perianal Crohn disease has been reported in 13% to 43% of patients with Crohn disease.1–4 Perianal Crohn disease can broadly be categorized into that associated with an anal canal or distal rectal stricture and that not associated with such a fibrotic obstruction. The former is by far more challenging to treat. Manifestations of perianal Crohn disease include skin lesions such as Crohn tags, as well as anal canal lesions such as perianal abscesses, fistulas, and fissures.5 Treatment is further complicated by the presence of disease immediately proximal to the anal canal within the rectum and colon or higher within the gastrointestinal tract. As with all suppurative processes in the perirectal area, the more frequent the number of bowel movements, the worse the symptoms. This is naturally also true for Crohn, particularly in the case of rectovaginal fistulas. We undertook a review of a group 86patients with perianal Crohn disease from a larger group of consecutively treated Crohn patients to determine whether there were patient or disease characteristics that were associated with failure of surgical treatment with respect to preservation of intestinal continuity. Recognition of such scenarios would permit more effective discussions with the patient and choice of treatment options.

METHODS

Written informed consent, including research authorization for use and disclosure of health care information for research, was obtained from all patients. Patients were derived from the clinical practice of the Section of Colon and Rectal Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Louisville. Participants were accrued prospectively and derived from a relatively small rural geographical area consisting primarily of Kentucky and southern Indiana. This is atypical since inflammatory bowel disease is typically more prevalent in urban populations.6 Clinical data were entered into a customized, password-protected Microsoft Access relational database designed to organize, calculate, tabulate, graph, and export information about IBD patients for analysis. All patients were followed prospectively and clinical data verified and periodically updated. The following data were obtained: gender, age, age of disease diagnosis, type of perianal Crohn disease, other sites of disease location, and number and type of previous surgical procedures. For purposes of this study, we excluded Crohn-disease patients who had only anal skin lesions (such as Crohn skin tags) and no anal canal Crohn lesions. “Anal-canal stricture” referred to a fibrotic anal-canal stricture, which did not permit passage of an adult-sized proctoscope (18-mm diameter) without dilatation. “Diversion” referred to the need for a temporary or permanent stoma at any time during the patient's clinical care. “Permanent stoma” referred to either a patient who had undergone proctectomy with excision of the anal sphincter or to a patient who had a stoma (ileostomy or colostomy) above an anal canal so damaged by Crohn disease or surgery for this disease that stoma closure was not feasible.

Statistical Analyses

For continuous variables, comparisons were done using 2-sample t tests. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson χ2 test or Fisher exact test in cases where any cell sample size was less than 5. Univariate odds ratios were computed using logistic regression. Multivariate analysis was conducted using multivariate logistic regression. All calculations were done using JMP from SAS, Inc. (Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Of the 356 consecutively treated patients with Crohn disease who have been prospectively accrued into our inflammatory bowel disease database since 1997, 86 patients had coexisting anal canal Crohn disease (24%). While males predominated in those patients without perianal Crohn disease (188 men, 82 women [30%]), women were more common among those patients with perianal disease (37 men, 49women [57%], P < 0.0001).

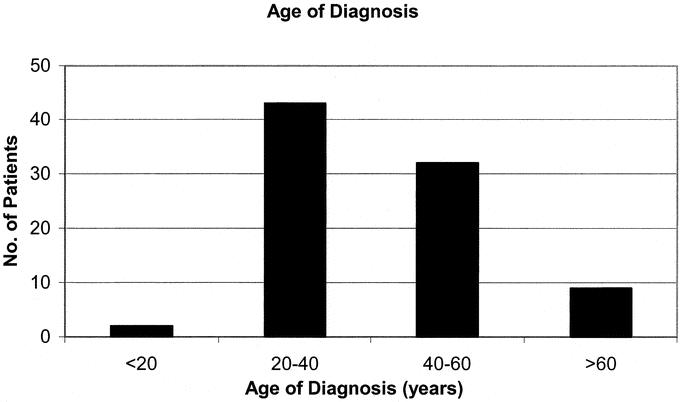

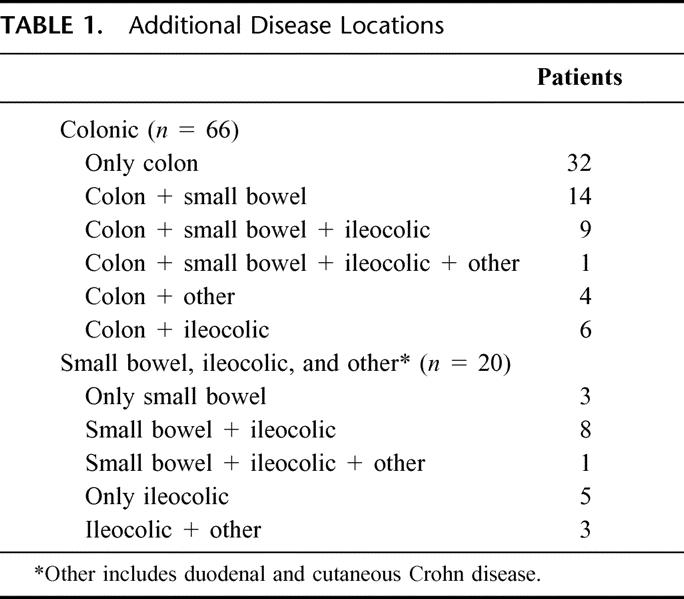

Although the age of presentation varied greatly from 14to 83 years, the majority of patients were diagnosed between 20 and 40 years of age (Fig. 1). Other sites of Crohn disease involvement were limited to the small bowel and/or ileocolic area in only 23% of patients. The remainder of patients all had some degree of colorectal Crohn disease, the more distally located bowel disease being much more common in patients with perianal Crohn disease. The disease locations in addition to perianal Crohn disease are shown in Table 1.

FIGURE 1. Age at diagnosis of Crohn disease (years).

TABLE 1. Additional Disease Locations

The presence of 1 or more perirectal fistula(s) was the most common type of perianal Crohn disease and occurred in 75 patients (87%). This was followed in frequency by fissure in 38 patients (44%), anal-canal stricture in 32 patients (37%), and rectovaginal fistula, which occurred in 20 of 49women (41% of women).

Initially, all patients had been treated with either mesalamine or sulfasalazine, and all but 1 patient had been placed on metronidazole or another oral antibiotic. Eighty-one patients (94%) had been treated with systemic steroids, and 73 patients (85%) had been treated with immunomodulators (either antimetabolites, infliximab, or in many cases both).

Information regarding the timing of the development of anal Crohn disease with respect to the diagnosis of Crohn disease was only available for 33% of patients. For these patients, the perianal disease was diagnosed at a mean of 6.5years after disease diagnosis (range 0–18, median 5.5years). In these patients, surgery for their perianal disease was performed at a mean of 7 years after disease diagnosis (range 0–20 years, median 6 years).

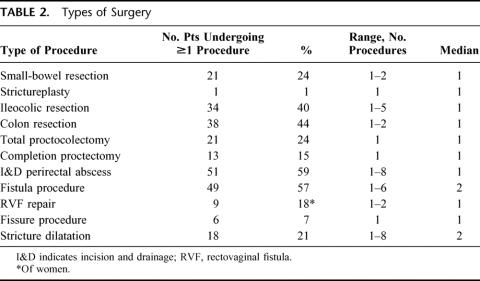

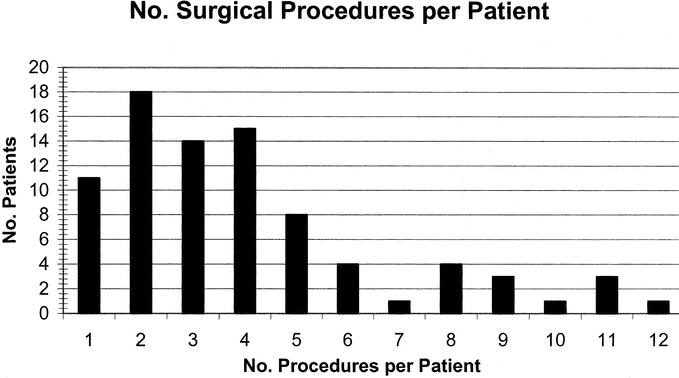

Eighty-six patients underwent 344 operations. Figure 2 illustrates the number of surgical procedures performed per patient. The number of procedures ranged from 1 to 12(mean ± SD, 4.0 ± 2.7, median 3). The types of surgery performed in these patients are shown in Table 2. Overall, 53patients (62%) required fecal diversion at some point during their care. Forty-two patients (49%) required a permanent stoma. These were ileostomies in all except 2 patients who had colostomies and in whom colon was conserved due to coexisting short-bowel syndrome due to extensive prior small-bowel resections. Twenty-seven patients (31%) had fistulizing intraabdominal disease.7 This was not associated with a greater need for diversion or permanent stoma (Table 3).

FIGURE 2. Number of surgical procedures per patient.

TABLE 2. Types of Surgery

TABLE 3. Analyses of Risk Factors for Diversion and Permanent Stoma

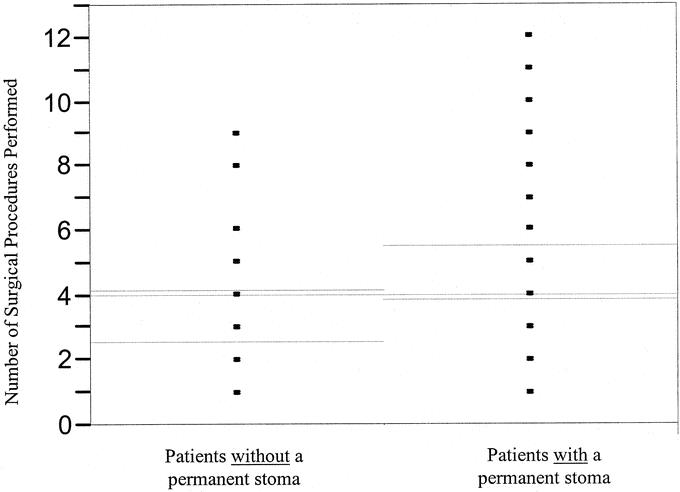

In 4 patients in whom the lower rectum was supple enough to permit stapled closure, an ultralow Hartmann procedure was performed to avoid a perineal wound. In 42patients (49%), fecal diversion is permanent; however, other patients may still require diversion at some time in the future. The mean number of surgical procedures performed was higher in patients requiring diversion (4.5 versus 3.2, P= 0.0305) and in patients requiring a permanent stoma (4.7 versus 3.4, P = 0.0223) (Fig. 3). Similarly, as the number of surgical procedures increased, so did the likelihood that the patient would require diversion (P = 0.0380) or a permanent stoma (P = 0.0285).

FIGURE 3. Number of surgical procedures performed in patients without a permanent stoma and in patients with a permanent stoma. Comparison using a 2-sample t test. Gray lines indicate overall means; green lines indicate 95% confidence intervals; P = 0.0223.

Rectovaginal fistula was by itself not associated with the requirement for diversion or permanent stoma (Table 3). The presence of an anal stricture, although not associated with the need for diversion, was associated with the need for a permanent stoma. Sixty-one percent of patients without anal-canal stricture were able to avoid a permanent stoma compared with only 34% of those patients with an anal-canal stricture. Interestingly, patients with anal stricture who performed self-dilation of these strictures using Hegar dilators were less likely to require diversion (P = 0.0193). Patients undergoing colonic resection were more likely to require diversion or permanent stoma (Table 3). In contrast, patients undergoing ileocolic resection were less likely to require diversion or permanent stoma.

In the multivariate model, the presence of colonic disease and anal-canal stricture was significantly associated with the need for permanent stoma (P = 0.0035 and P = 0.0105, respectively). The overall odds ratio of requiring a permanent stoma in the presence of colonic Crohn disease in addition to perianal Crohn disease was 5.42, while this rose to 33 in the presence of both colonic Crohn disease and the presence of an anal-canal stricture (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The incidence of perianal Crohn disease varies, depending on differences in case mix, referral basis, and on the working definition of what actually constitutes perianal Crohn disease. We did not include patients without anal-canal disease in the present study. Fissures, fistulas, abscesses, and anal-canal stenosis are presenting manifestations of significant perianal Crohn disease. There are no known predictors of which patients will fail medical and/or sphincter-sparing surgical therapy and ultimately require fecal diversion. The severity of associated symptoms will to some degree depend on the severity of the associated nonperineal Crohn disease, if any. In other words, generally the worse the diarrhea, the more symptomatic the anal Crohn disease. There have been several classification systems specifically designed for perineal Crohn disease. The Cardiff classification described in 1978 by Hughes8,9 assigned a score of 0 to 2 for each manifestation of perianal Crohn disease: ulceration, fistula, and stricture, and also classified fistula location with respect to the dentate line. A later modification added a score for proximal intestinal Crohn disease.9 Other perianal Crohn disease activity indices have also been described.10,11 Neither of these systems has been widely used or useful in indicating which patients and disease characteristics are in particular associated with failure of maintaining intestinal continuity. It is for this reason that we undertook the present study.

Our finding that perianal disease is more common in patients with colitis and ileocolitis than in small-bowel disease is in agreement with reports from others.12 In a study of 323 patients with Crohn colitis, Makowiec and colleagues13 found the presence of perianal disease to be an adverse risk factor with respect to preserving the colon. Several studies have noted that the presence of perianal Crohn disease in general is associated with a higher rate of recurrence of Crohn disease and a shorter median time to recurrence.14,15

In our patients, approximately half ultimately required a permanent stoma. This is somewhat comparable to the 33% rate of permanent stoma reported by van Dongen and Lubbers.4 Guillem et al16 found that the presence of both perianal disease and Crohn colitis predicted persistent or recurrent disease in excluded rectal segments after temporary fecal diversion and argued that primary total proctocolectomy or early completion proctectomy might be indicated in this scenario. Some believe that diversion should be used with caution in patients with anal stenosis due to the possibility of symptomatic disease developing in the proximal defunctioned bowel.17

Several studies have reported a relatively benign course of perianal Crohn disease, with relatively low rates of proctectomy (<21%) for perianal Crohn disease.4,18–20 For example, in Fry et al's report,19 proctectomy was required in only 12% of patients with suppurative perianal Crohn disease. Several factors may explain the apparently more virulent disease in our population, with nearly one half of our patients requiring a permanent stoma.

In some reports, perianal skin tags and fissures account for a significant number of patients with perianal Crohn disease. In the present study, Crohn tags alone were not believed to represent significant Crohn disease, and therefore in the absence of coexisting anal canal Crohn disease, patients with such lesions were excluded.

The high rate of cigarette smoking in the state of Kentucky and specifically in our patient population may be one factor possibly related to the more virulent course of the Crohn disease reported herein. As numerous studies have shown, cigarette smoke has a deleterious effect on Crohn disease, significantly exacerbating its symptoms. Cigarette smoking has also been associated with a higher rate of postoperative disease recurrence.21–24 We are currently administering modified Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) and childhood tobacco exposure questionnaires to our patients to more objectively assess their tobacco-smoke exposure.25,26

In a series of 102 patients with perianal Crohn disease, Bernard and associates27 noted that more than 1 type of perianal Crohn lesion developed in 59% of patients. We also found this to be true, where many patients had more than 1 type of perianal lesion, two thirds of fistula patients having an associated abscess and one fourth of fistula patients having an associated anal canal stricture. As others, we have treated low fistulas with primary fistulotomy and high fistulas and horseshoe fistulas with draining setons,28,29 the latter usually combined with infliximab therapy and immunosuppressives.30,31 There is some evidence that there is a better response to infliximab, lower fistula recurrence rate, and longer time to recurrence when infliximab treatment is preceded by an examination under anesthesia and seton placement.32 In the absence of significant rectal mucosal disease, advancement flap repairs were also used, either with or without diversion. The presence of Crohn disease has, however, been shown to have a negative impact on the healing of endorectal advancement flap repairs for anorectal and rectovaginal fistulas.33,34

An anal-canal stricture, particularly when associated with suppurative disease, seems to be a bad prognostic indicator of the likelihood of preserving intestinal continuity. In the report by Linares et al,35 roughly half the patients with anal canal strictures required fecal diversion despite repeated dilatations among other treatments. In our patients, only 34% of patients with an anal-canal stricture avoided a permanent stoma. Anal-canal stricture and colonic Crohn disease were the 2 factors that remained predictors of the need for permanent stoma on multivariate analysis.

Our data clearly show that (1) in the presence of both anal-canal stricture and colonic Crohn disease, there is an over 30-fold increased likelihood of permanent stoma; (2) self-dilatation of such anal-canal strictures may help avert the need for diversion; (3) patients with colonic disease are at high risk of requiring permanent stoma, and those undergoing ileocolic resection at lower risk; and (4) as the number of surgical procedures increases, so does the chance of permanent stoma. Careful patient assessment, frank discussion of risk factors, and appropriate choice of therapy are essential to select the most suitable and effective treatment of the individual patient.

Discussions

Dr. David B. Adams (Charleston, South Carolina): I would like to congratulate Dr. Galandiuk and her colleagues for this excellent analysis of perianal Crohn's disease and the identification of factors which predict the need for fecal diversion. Anal-canal stenosis and colonic disease were factors that clearly predicted the need for fecal diversion.

When Crohn, Ginzberg, and Oppenheimer reported their observations about regional ileitis to the Section of Gastroenterology and Proctology at the AMA meeting in New Orleans in 1932, the discussion following involved 5physicians whose comments were recorded on about 125lines of type with only 3 short questions posed. I have more questions than comments today.

In Dr. Burill Crohn's response to his commentators, he noted that when he spoke to men with broad surgical and medical experience about this puzzling disease, their frequent response was, “We have seen such a thing in past years. We have met with it in surgical experience. And we don't know what to do with it.”

When to divert for Crohn's disease is a similar problem. We see it, but we don't know when to divert. Dr. Galandiuk's prospectively accrued data have given us many valuable answers, but many questions remain. The questions that I would like to ask today have been posed recently by myself or by patients.

Does your database allow you to predict earlier which patients will require diversion and avoid operations with a low success rate in this disorder? If so, which operations for perianal Crohn's disease are best avoided? Could you clarify situations in which diversion is a temporary procedure? Could you clarify whether intractable diarrhea and/or incontinence are independent indicators for diversion? Is Crohn's disease shifting southward or is the number of cases the reflection of a specialized university service?

At our annual postgraduate course in surgery this year, a participant lamented the recommendation that he should send all his esophageal and pancreatic cancer to specialized centers. “What's left for the general surgeon,” he moaned, “hemorrhoids?” “Oh, no, don't operate on hemorrhoids,” our colorectal specialist said. The question that comes to mind thusly is, should complicated perianal Crohn's disease be referred to a colorectal specialist?

You have demonstrated beautifully the power and bounty of prospective data accrual. Could you tell us something of the logistics involved with this? Does it require full-time data manager, a research nurse; is routine follow-up done; what is the cost and who bears it?

Dr. Richard R. Ricketts (Atlanta, Georgia): Just 1question relative to your opening statement. In your abstract, you mentioned that 64% of women with retrovaginal fistulas required permanent diversion, and that was not mentioned in the presentation. I would like to know what the data are on that, please.

Dr. J. Patrick O'Leary (New Orleans, Louisiana): This is a naive question, but do you have to resect the rectum to get the kind of response that you showed if you created a permanent stoma?

Dr. Susan Galandiuk (Louisville, Kentucky): First, regarding questions of Dr. Adams, regarding the indications for stoma: One of the worst adverse variables is the presence of truly fibrotic disease. These are strictures that are difficult to dilate even using your finger. Pliable strictures tend to respond well to antiinflammatory medications, as well as to other types of medical therapy. The very fibrotic disease is the worst to treat.

Incontinence and diarrhea in itself is not an indication for diversion, unless it is due to very severe distal disease. And even then it depends to some extent on what the incontinence is due to. If it is due to a very large rectovaginal fistula, clearly this is an incapacitating symptom for women that needs to be treated with diversion. If the incontinence and diarrhea is just due to systemic Crohn's disease (ie due to proximal gastrointestinal Crohn's disease), in many cases, treating this will improve the anorectal symptoms to the extent that patients don't require diversion. It is very important to work closely with your gastroenterologist and optimize medical treatment.

I have found it amazing how many gastroenterologists will treat anal-canal Crohn's and will not have done a digital exam. They wonder why their patient has incontinence and diarrhea and has not responded to therapy. They have not identified that their patient has severe anal-canal stricture and then wonder why their immunosuppressive therapy and immunomodulators aren't working. In these cases, it is actually a mechanical problem. Similarly, in such cases perianal fistulas progress because there is distal obstruction. It is similar to any other fistula, with a distal obstruction, the fistula won't heal.

In response to the question: “Is Crohn's disease shifting southward?” I don't think so. In my own practice, we see a lot of perianal Crohn's disease, but in our cohort, it still affected only 23% of patients, which is still a relatively low number.

How does our database work and is it expensive to operate? Yes. We combine it with our laboratory database with a combined clinical and genetic database. We collect genomic DNA from our IBD patients. Our database is a Web-based database. Patients sign a HIPAA release, so that we can use their clinical information. Genetic and clinical data are all entered in the same database. We have a full-time research study coordinator, as well as a part-time study coordinator, who continually updates patient information. There is a lot of work involved in maintaining it.

Regarding Dr. Ricketts’ question on the rectovaginal fistula, we initially thought that was going to be a significant factor; however, on both univariate and multivariate analyses, it turned out that rectovaginal fistula itself was not a significant factor. Anal-canal stricture which was sometimes associated with it was actually the significant factor.

With respect to Dr. O'Leary's question, is it always necessary to resect the rectum? No, really. In some patients, in order to eliminate a nonhealing perineal wound, one can do an ultralow Hartmann's procedure. That is, however, limited by the ability to be able to transect the rectum very low. Sometimes the distal rectum is so fibrotic that you literally can't get a linear stapler to fire across it. In those patients, you have to do a proctectomy in order to remove the organ. Otherwise you would have a nonhealing open rectal stump that you couldn't close.

Footnotes

Reprints: Susan Galandiuk, MD, Professor of Surgery and Program Director, Section of Colon and Rectal Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Louisville School of Medicine, Louisville, KY 40292. E-mail: s0gala01@gwise.louisville.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: perianal Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1503–1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz DA, Pemberton JH, Sandborn WJ. Diagnosis and treatment of perianal fistulas in Crohn disease. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:906–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lapidus A, Bernell O, Hellers G, et al. Clinical course of colorectal Crohn's disease: a 35-year follow-up study of 507 patients. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1151–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Dongen LM, Lubbers EJ. Perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. Arch Surg. 1986;121:1187–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandborn WJ, Fazio VW, Feagan BG, et al. AGA technical review on perianal Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1508–1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hugot JP, Zouali H, Lesage S, et al. Etiology of the inflammatory bowel diseases. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1999;14:2–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gasche C, Scholmerich J, Brynskov J, et al. A simple classification of Crohn's disease: report of the Working Party for the World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna 1998. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2000;6:8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes LE. Surgical pathology and management of anorectal Crohn's disease. J R Soc Med. 1978;71:644–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughes LE. Clinical classification of perianal Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:928–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pikarsky AJ, Gervaz P, Wexner SD. Perianal Crohn disease: a new scoring system to evaluate and predict outcome of surgical intervention. Arch Surg. 2002;137:774–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allan A, Linares L, Spooner HA, et al. Clinical index to quantitate symptoms of perianal Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:656–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rankin GB, Watts HD, Melnyk CS, et al. National Cooperative Crohn's Disease Study: extraintestinal manifestations and perianal complications. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:914–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makowiec F, Schmidtke C, Paczulla D, et al. Progression and prognosis of Crohn's colitis. Z Gastroenterol. 1997;35:7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whelan G, Farmer RG, Fazio VW, et al. Recurrence after surgery in Crohn's disease: relationship to location of disease (clinical pattern) and surgical indication. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:1826–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernell O, Lapidus A, Hellers G. Risk factors for surgery and recurrence in 907 patients with primary ileocaecal Crohn's disease. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1697–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guillem JG, Roberts PL, Murray JJ, et al. Factors predictive of persistent or recurrent Crohn's disease in excluded rectal segments. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:768–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williamson ME, Hughes LE. Bowel diversion should be used with caution in stenosing anal Crohn's disease. Gut. 1994;35:1139–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buchmann P, Keighley MR, Allan RN, et al. Natural history of perianal Crohn's disease: ten year follow-up: a plea for conservatism. Am J Surg. 1980;140:642–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fry RD, Shemesh EI, Kodner IJ, et al. Techniques and results in the management of anal and perianal Crohn's disease. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1989;168:42–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bell SJ, Williams AB, Wiesel P, et al. The clinical course of fistulating Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1145–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindberg E, Jarnerot G, Huitfeldt B. Smoking in Crohn's disease: effect on localisation and clinical course. Gut. 1992;33:779–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duffy LC, Zielezny MA, Marshall JR, et al. Cigarette smoking and risk of clinical relapse in patients with Crohn's disease. Am J Prev Med. 1990;6:161–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sutherland LR, Ramcharan S, Bryant H, et al. Effect of cigarette smoking on recurrence of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:1123–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cottone M, Rosselli M, Orlando A, et al. Smoking habits and recurrence in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:643–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seifert JA, Ross CA, Norris JM. Validation of a five-question survey to assess a child's exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12:273–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2002.

- 27.Bernard D, Morgan S, Tasse D. Selective surgical management of Crohn's disease of the anus. Can J Surg. 1986;29:318–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sangwan YP, Schoetz DJ Jr, Murray JJ, et al. Perianal Crohn's disease: results of local surgical treatment. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:529–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott HJ, Northover JM. Evaluation of surgery for perianal Crohn's fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:1039–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Topstad DR, Panaccione R, Heine JA, et al. Combined seton placement, infliximab infusion, and maintenance immunosuppressives improve healing rate in fistulizing anorectal Crohn's disease: a single center experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:577–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McNamara DA, Brophy S, Hyland JMP. Perianal Crohn's disease and infliximab therapy. Surg J R Coll Surg Edinb Irel. 2004;2:258–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Regueiro M, Mardini H. Treatment of perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease with infliximab alone or as an adjunct to exam under anesthesia with seton placement. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2003;9:98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sonoda T, Hull T, Piedmonte MR, et al. Outcomes of primary repair of anorectal and rectovaginal fistulas using the endorectal advancement flap. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1622–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mizrahi N, Wexner SD, Zmora O, et al. Endorectal advancement flap: are there predictors of failure? Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1616–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Linares L, Moreira LF, Andrews H, et al. Natural history and treatment of anorectal strictures complicating Crohn's disease. Br J Surg. 1988;75:653–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]