Abstract

Objective:

Our aims were to (1) determine the long-term oncologic outcome for patients with rectal cancer treated with preoperative combined modality therapy (CMT) followed by total mesorectal excision (TME), (2) identify factors predictive of oncologic outcome, and (3) determine the oncologic significance of the extent of pathologic tumor response.

Summary Background Data:

Locally advanced (T3–4 and/or N1) rectal adenocarcinoma is commonly treated with preoperative CMT and TME. However, the long-term oncologic results of this approach and factors predictive of a durable outcome remain largely unknown.

Methods:

Two hundred ninety-seven consecutive patients with locally advanced rectal adenocarcinoma at a median distance of 6cm from the anal verge (range 0–15 cm) were treated with preoperative CMT (radiation: 5040 centi-Gray (cGy) and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)-based chemotherapy) followed by TME from 1988 to 2002. A prospectively collected database was queried for long-term oncologic outcome and predictive clinicopathologic factors.

Results:

With a median follow-up of 44 months, the estimated 10-year overall survival (OS) was 58% and 10 year recurrence-free survival (RFS) was 62%. On multivariate analysis, pathologic response >95%, lymphovascular invasion and/or perineural invasion (PNI), and positive lymph nodes were significantly associated with OS and RFS. Patients with a >95% pathologic response had a significantly improved OS (P = 0.003) and RFS (P = 0.002).

Conclusions:

Treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer with preoperative CMT followed by TME can provide for a durable 10-year OS of 58% and RFS of 62%. Patients who achieve a >95% response to preoperative CMT have an improved long-term oncologic outcome, a novel finding that deserves further study.

We provide a comprehensive analysis of the long-term oncologic outcome of rectal cancer treated with preoperative combined modality therapy and radical resection. In addition, we identify factors predictive of a durable oncologic outcome and define the impact of extent of pathologic response.

Based largely upon the results of 2 large multicenter randomized trials, an NIH-sponsored Consensus Conference in 1990 recommended postoperative combined modality therapy (CMT) for stage II and stage III rectal cancer.1–3 The effectiveness of postoperative CMT in this setting led to the evaluation of preoperative CMT in the treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer.4–20 A recently completed prospective randomized trial has demonstrated that preoperative CMT provides for superior sphincter preservation rates and local control when compared with postoperative CMT.21 However, there was no significant difference in overall survival between the groups receiving preoperative and postoperative CMT.21

Local recurrence rates for locally advanced rectal cancer treated with preoperative CMT and radical rectal resection have been reported to range from 0% to 30%, recurrence-free survival (RFS) from 59% to 90%, and overall survival (OS) from 60% to 100%.4–15,17–21 Although encouraging, the studies generating these results have several limitations and must be interpreted carefully. First, the studies lacked standardization of CMT regimens and surgical technique. Some studies were based on small sample sizes with inadequate follow-up intervals. In addition, there is a lack of data available concerning predictors of outcome and the importance of pathologic tumor response to oncologic outcome.

It has been reported that preoperative CMT can achieve a pathologic complete response (pCR), defined as no viable tumor cells in the resection specimen, in 5% to 33% of patients with rectal cancer and that these patients may have an improved oncologic outcome.4–9,15–18,21–28 Additionally, we have previously reported that patients who achieve a near-complete (>95%) pathologic response to preoperative CMT may benefit from an improvement in oncologic outcome.17 However, the impact of the extent of pathologic response on long-term oncologic outcome remains unclear.

Therefore, our aims were to (1) determine the long-term oncologic outcome for patients with rectal cancer treated with preoperative CMT followed by TME, (2) identify factors predictive of a durable oncologic outcome, and (3) determine the oncologic significance of the extent of pathologic tumor response.

METHODS

Patient Population

The study group consisted of 297 consecutive patients with locally advanced (endorectal ultrasound T3–4 or N1 and/or clinically bulky) primary rectal adenocarcinoma, treated at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center between 1988 and 2002. All patients had biopsy-proven rectal adenocarcinoma (median distance from anal verge, 6.0 cm; range, 0–15 cm). Patients with recurrent rectal cancer were excluded.

The prospectively collected Colorectal Service database, supplemented by a comprehensive chart review, was queried to determine local recurrence, distant metastases, OS, and RFS. In addition, clinical and pathologic factors were evaluated for their association with local recurrence, distant metastases, and OS.

Preoperative CMT

A total of 277 patients (93%) received 5-FU-based chemotherapy, either by bolus (n = 259, 87%) or continuous infusion (n = 18, 6%). The remaining 20 patients (7%) had preoperative chemotherapy with irinotecan.

The most common protocol for bolus chemotherapy was 5-FU (325 mg/m2/d) with leucovorin (20 mg/m2/d) given for 2 cycles of 5 consecutive days on weeks 1 (days 1–5) and 5 (days 29–33) of radiation therapy. The most common protocol for continuous infusion chemotherapy was 5-FU (225 mg/m2/d) for a 6-week continuous cycle. Irinotecan was most commonly administered as a bolus infusion of 10mg/m2/d for a 4-week continuous cycle.

External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) (median dose, 5040 cGy; range, 1980–5400 cGy) was delivered according to previously published techniques.29 EBRT was most commonly delivered using 15-Mv photons via 3 or 4 field techniques. The perineum was blocked as much as possible in the lateral fields. EBRT was delivered in 26 fractions of 180 cGy per day, 5 days per week, for a total of 4680 cGy. Two boost doses of 180 cGy were delivered to the primary tumor bed for a total dose to the tumor of 5040 cGy. Four patients had EBRT doses of less than 4500 cGy; 1 required dose attenuation due to prior pelvic irradiation for Hodgkin disease, and 3 required early termination of therapy due to severe gastrointestinal toxicity.

In addition to preoperative CMT, 255 patients (86%) received postoperative chemotherapy. A total of 239 patients (94%) were treated with postoperative 5-FU and leucovorin. The remaining 16 patients (6%) were treated with 5-FU and leucovorin with either oxaliplatin, irinotecan, or other agents.

Surgical Resection

Patients underwent radical rectal cancer resection, according to the principles of total mesorectal excision (TME),30,31 at a median interval of 42.5 days (range: 25 to 95days) from the completion of preoperative CMT. Briefly, the technique of TME involved sharp dissection of the mesorectum in the avascular, areolar plane between the visceral fascia of the mesorectum and the parietal fascia overlying the pelvic sidewall. For middle and low rectal cancers, the entire mesorectum was mobilized and resected as an intact unit. For high rectal cancers, the mesorectum was divided at a right angle to the bowel, 5 cm distal to the mucosal edge of the tumor.

Pathologic Analysis

Standard pathologic analysis was performed on all radical rectal resection specimens. The rectal tumor was staged according to the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 5th edition.32 In addition, pathologic features such as lymphovascular invasion (LVI), perineural invasion (PNI), distal resection margin involvement, circumferential resection margin (CRM) involvement, and extent of tumor response were documented.

Areas of tumor treatment response were characterized by the replacement of neoplastic glands with loosely collagenized fibrous tissue and scattered chronic inflammatory cells, as previously reported from our institution.17,33 Particular note was made for tumors achieving a pCR (no viable tumor) or near-complete response (≥95% response).

Determination of Recurrence

The prospectively collected Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Colorectal Service database, supplemented by a comprehensive chart review, was queried to determine the incidence and type of local and/or distant recurrence. Local recurrence was defined as clinical, radiologic, and/or pathologic determination of rectal cancer recurrence in the prior pelvic treatment field. Distant recurrence was defined as clinical, radiologic, and/or pathologic determination of rectal cancer recurrence at any other site, including, but not limited to, the liver, lungs, and retroperitoneum.

Statistical Analysis

Proportions were compared with a 2-sided Fisher exact test. RFS and OS curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test and Cox regression analysis were used to identify factors significantly associated with local recurrence, distant metastases, and OS. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS Software system (version 11.0; Chicago, IL). A P value of less than or equal to 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The study was reviewed and approved by the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Patients

The study group consisted of 186 (63%) males and 111 (37%) females. The median age was 62 years (range, 25 to 90years). Two hundred ten patients (71%) had a sphincter-preserving procedure with a low anterior resection (LAR). Eighty-six patients (29%) required an abdominoperineal resection. One patient (<1%) underwent a total proctocolectomy. In the LAR group, 109 patients (52%) had restoration of bowel continuity with a coloanal anastomosis.

Pathologic Analysis

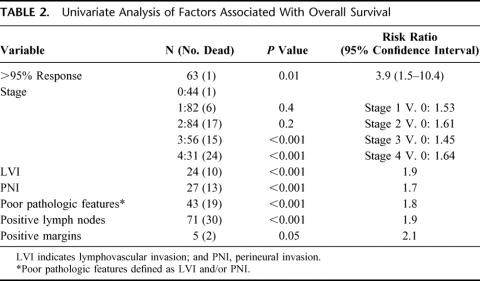

Forty-four patients (15%) achieved a pCR. In addition, 19 patients (6%) achieved a greater than 95% pathologic response but did not achieve a pCR (Table 1). There was no difference in pCR or near-complete pathologic response rate based upon the interval from completion of EBRT and surgery (P = 0.8).

TABLE 1. Summary of Pathologic Stages of Study Group

Of the 297 resected specimens, only 5 (2%) had a positive histologic margin. All positive margins were due to CRM involvement. There were no patients with positive proximal or distal margins.

Patterns of Local and Distant Recurrence

A total of 67 patients (23%) developed either local or distant rectal cancer recurrence. Of the 297 patients in our series, 7 (2%) had a local recurrence only, while 55 patients (19%) had a distant recurrence only. In addition, 5 patients (2%) had both a local and a distant recurrence.

One patient (2%) with a pCR developed recurrent disease. The recurrence was documented in the lungs 10months after radical rectal resection. In addition, 2 patients (11%) with a near-complete (>95%) response developed recurrent disease, 1 in the spine 16 months after rectal resection and 1 in the lungs 96 months after rectal resection. In the 234 patients with a less than 95% pathologic response, 64 (27%) developed either local or distant rectal cancer recurrence. The recurrence was local only in 7 patients (3%), distant only in 52 patients (22%), and local and distant in 5 patients (2%).

Local and Distant Failure Greater Than 5 Years After Preoperative CMT and TME

Of the 67 patients who developed recurrent disease, 4 (6%) had recurrent disease documented greater than 5 years following surgery. Three of these 4 patients had a distant recurrence, and 1 had both a local and distant recurrence. The recurrences were documented 61, 71, 76, and 96 months following curative rectal resection. Conversely, only 1 patient who achieved a near-complete pathologic response and no patients who achieved a pCR developed a recurrence greater than 2 years following preoperative CMT and TME.

Overall Survival

With a median follow-up of 44 months (range, 0.8 to 128.6 months), 63 patients (21%) died of rectal cancer. The median OS was not reached. The estimated 5-, 7-, and 10-year OS was 76%, 63%, and 58%, respectively (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1. Five-year and 10-year overall survival of study population, with 95% confidence intervals.

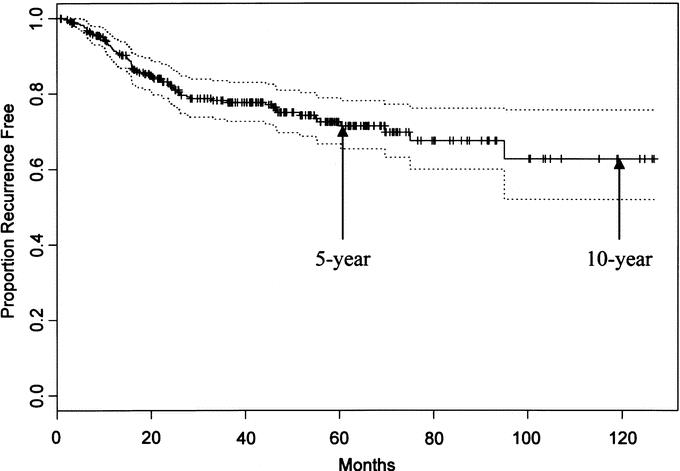

RFS

With a median follow-up of 47 months for survivors, 67 patients (23%) developed rectal-cancer recurrence. The median RFS was not reached. The estimated 5-, 7-, and 10-year RFS was 73%, 68%, and 62%, respectively (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2. Five-year and 10-year recurrence-free survival of study population, with 95% confidence intervals.

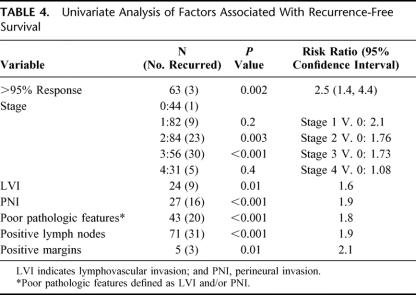

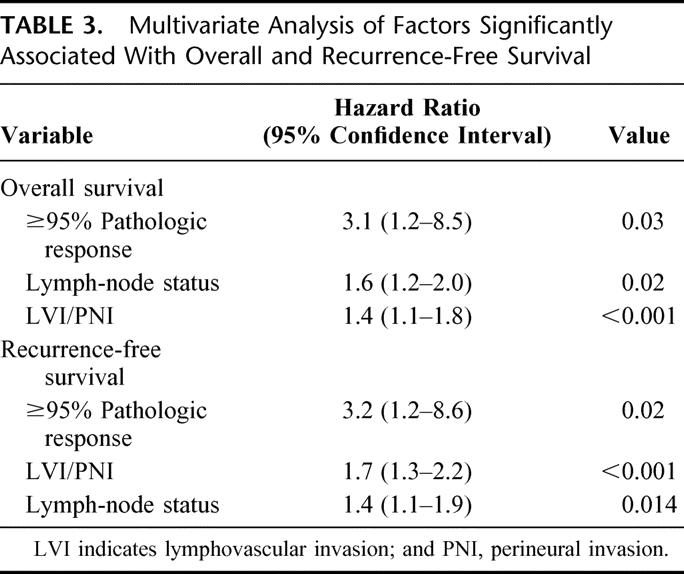

Factors Associated With Overall Survival

On univariate analysis, a pathologic response greater than 95% (P < 0.01), pathologic stage III and IV (P < 0.001), LVI and/or PNI (P < 0.001), positive lymph nodes (P< 0.001), and positive resection margins (P = 0.05) were significantly associated with OS (Table 2). When these factors were analyzed using a multivariate model, pathologic response greater than 95% (P = 0.03), positive lymph nodes (P = 0.02), and LVI and/or PNI (P < 0.001) were significantly associated with OS (Table 3).

TABLE 2. Univariate Analysis of Factors Associated With Overall Survival

TABLE 3. Multivariate Analysis of Factors Significantly Associated With Overall and Recurrence-Free Survival

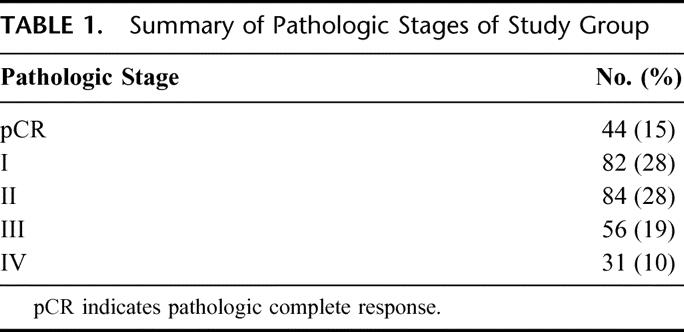

Factors Associated With RFS

On univariate analysis, pathologic response greater than 95% (P = 0.002), pathologic stage III (P < 0.001), LVI and/or PNI (P < 0.001), positive lymph nodes (P < 0.001), and positive resection margins (P = 0.01) were significantly associated with RFS (Table 4). When these factors were analyzed using a multivariate model, pathologic response greater than 95% (P = 0.02), LVI and/or PNI (P < 0.001), and positive lymph nodes (P = 0.01) were significantly associated with RFS (Table 4).

TABLE 4. Univariate Analysis of Factors Associated With Recurrence-Free Survival

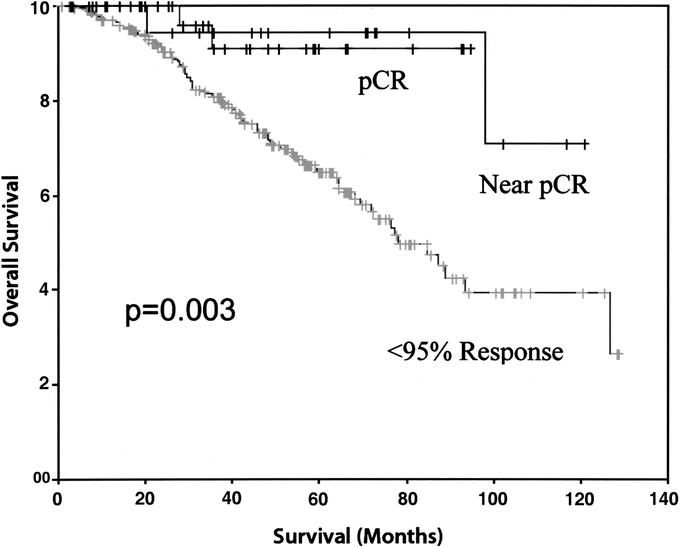

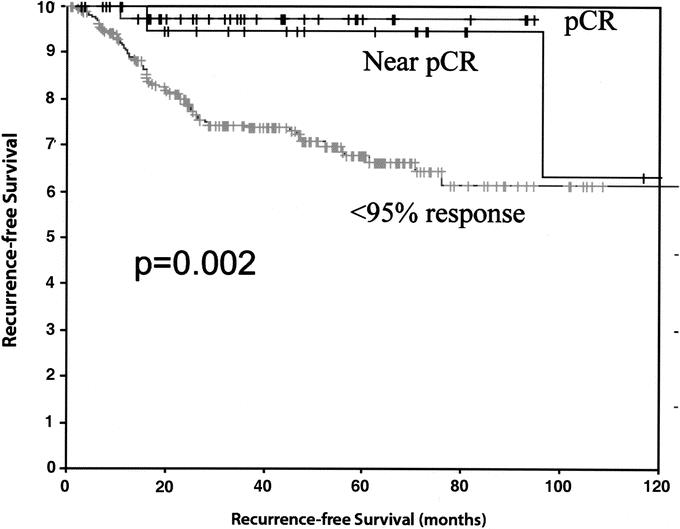

Survival Analysis: pCR and Greater Than 95% Pathologic Response

The estimated 5-, 7-, and 10-year OS in the pCR group was 89%, 89%, and 89%, respectively. The estimated 5-, 7-, and 10-year OS in the greater than 95% response group was 93%, 93%, and 72%, respectively. The 5-, 7-, and 10-year OS was not significantly different between the pCR and greater than 95% response group (P = 0.6).

The estimated 5-, 7-, and 10-year RFS in the pCR group was 98%, 98%, and 98%, respectively. The estimated 5-, 7-, and 10-year RFS in the greater than 95% response group was 94%, 94%, and 64%, respectively. The 5-, 7-, and 10-year RFS was not significantly different between the pCR and greater than 95% response group (P = 0.6).

Survival Analysis: Greater Than 95% Pathologic Response Compared With Less Than 95% Pathologic Response

A total of 234 patients (79%) had a less than 95% pathologic response. The estimated 5-, 7-, and 10-year OS in the less than 95% pathologic response group was 67%, 48%, and 38%, respectively. The estimated 5-, 7-, and 10-year RFS in the less than 95% pathologic response group was 66%, 60%, and 60%, respectively. Notably, the pCR and greater than 95% pathologic response groups achieved a significantly improved OS (P < 0.003) and RFS (P < 0.002) when compared with the group that did not achieve a greater than 95% pathologic response (Figs. 3 and 4).

FIGURE 3. Comparison of overall survival between pCR (pathologic complete response, 100% response), near pCR (95%–99.9% response), and <95% pathologic response.

FIGURE 4. Comparison of recurrence-free survival between pCR (100% response), near pCR (95%–99.9% response), and <95% pathologic response.

DISCUSSION

We report, to our knowledge, the largest single-institution analysis of long-term oncologic outcome in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer treated with preoperative CMT and radical resection with TME. We have documented that 10-year OS is 58% and 10-year RFS is 62%. It is somewhat difficult to compare our long-term results with recent reports as median follow-up varies from 12 months to 69 months in the literature.4–15,17–21 Be that as it may, our reported OS compares well with the 60% to 100% reported in the literature.4–15,17–21 In addition, our RFS falls within the previously reported range of 60% to 90%.4–15,17–21 However, it must be emphasized that our 10-year OS and RFS represent the longest reported to date.

We also documented that a pathologic response greater than 95%, absence of LVI and/or PNI, and negative lymph nodes in the post-CMT pathologic specimen are independently predictive of improved long-term OS and RFS. Our results demonstrating a favorable outcome for cases with a pCR are in agreement with other studies based on smaller sample sizes and shorter follow-up.6,18,27,34 In addition, our current data, based on a large study population with mature follow-up, suggest that patients with a greater than 95% pathologic response but not having achieved a pCR may have a similar long-term prognosis as those who experience a pCR. Taken together, these data strongly support ongoing efforts to develop methods to increase the extent of pathologic response of rectal cancer to preoperative CMT. We have demonstrated that increasing the interval from completion of radiation to surgery may increase extent of pathologic response.35 Others have been able to increase pCR rates to 19% to 37% using chemotherapeutic regimens containing newer agents such as oxaliplatin, irinotecan, and capecitabine.36–44 Our results demonstrating a significantly improved survival for patients with a greater than 95% pathologic response also raise the question of whether this unique group of responders requires postoperative chemotherapy. However, further studies are required to identify the subset of patients with a greater than 95% response in whom postoperative chemotherapy can be withheld without incurring a negative impact on long-term oncologic outcome.

Currently, the data and recommendations for the postoperative surveillance period following curative rectal resection are unclear, although many clinicians follow an intensive program for at least 5 years. Our data suggest that rectal cancer recurrence may be delayed following preoperative CMT and TME and that surveillance of more than 5 years may be warranted. We report that a fraction of our patients with rectal cancer treated with preoperative CMT developed cancer recurrence more than 5 years following curative rectal resection, the longest interval being 96 months. However, after 5 years of follow-up, a local recurrence occurred in only 1 patient (0.3%). This compares favorably with the 3% local recurrence rate after 5 years of follow-up observed in the Intergroup 0114 trial in patients with rectal cancer treated with radical resection and postoperative chemoradiation.45 Conversely, we did not observe any recurrent disease more than 2 years after curative rectal resection in the group of patients with a pCR and only 1 recurrence greater than 2 years after curative rectal resection in the near-complete pathologic response group. These findings suggest the potential for planning postoperative surveillance for rectal cancer recurrence based upon pathologic tumor response and may warrant close follow-up greater than 5 years following treatment of primary rectal cancer with preoperative CMT and TME.

There are several limitations of this study that deserve mention. First, although we report a 10-year OS and RFS, our median follow-up was 44 months. However, we have used the Kaplan-Meier method to estimate 5-, 7-, and 10-year OS and RFS. Second, we performed a retrospective study, and therefore it is limited by the bias inherent to an analysis of this nature. Despite these limitations, we feel that our large study population and long-term follow-up allow us to make valid conclusions.

In summary, for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer treated with preoperative CMT and radical rectal resection with TME, the 5-, 7-, and 10-year OS can be expected to be 76%, 63%, and 58%, respectively. In addition, the 5-, 7-, and 10-year RFS in this population can be expected to be 73%, 68%, and 62%. A pathologic response greater than 95%, absence of LVI and/or PNI, and negative lymph nodes are all independent predictors of improved long-term oncologic outcome. Finally, patients who achieve a greater than 95% pathologic response have an improved long-term oncologic outcome, which may not be significantly different from those who achieve a pCR.

In conclusion, the treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer with preoperative CMT and radical rectal resection with TME currently provides the optimal treatment standard for a durable long-term oncologic outcome in properly selected patients. It is anticipated that it will continue to gain acceptance and increasing numbers of patients with locally advanced rectal cancer will be treated using this approach. However, insofar as a substantial fraction of patients will continue to recur after 5 years of follow-up, our results support postoperative surveillance programs beyond 5 years in this patient population. Large, multicenter trials are required to better define the patterns of disease recurrence for primary rectal cancer treated with preoperative CMT before specific postoperative surveillance programs can be recommended. Our work and that of others currently focuses on the identification of the biologic determinants governing rectal cancer response to preoperative CMT,46,47 evaluation of novel imaging modalities able to identify pCR or near-complete response preoperatively,33,48 and the development of novel therapeutic regimens capable of further increasing pCR rates.49,50

Discussions

Dr. Kirby I. Bland (Birmingham, Alabama): I rise to congratulate Dr. Guillem and Dr. Cohen for bringing this very important paper to the Association's attention.

The authors have confirmed in this particular analysis that preoperative chemoradiation together with a TME, as you have seen, has improved the overall durable 10-year overall survival, as well as relapse-free survival. And those numbers again were 58 and 62%, a very respectable number. Importantly, they have further documented that in this large single institute analysis, you have seen the factors that they have found that are pathologically important to make these predictions for overall and relapse-free survival. As presented, the authors have convinced us that the majority of these patients with rectal cancer treated with these combinations have improved outcomes.

Now, this is similar, and Ted Copeland brought this up earlier this morning, to the presentation we made in 1992. Using almost exactly the same regimen, only 5-FU, at the time as a sensitizer and as a preoperative chemotherapeutic, we showed an advancement with improvement in terms of not only overall but relapse-free survival. I think what you have seen today in the authors’ outcomes, that their local recurrence rates, which is embedded in the manuscript, [are] about 2%. That is the best recorded local recurrence rates that I am aware of. You may wish to comment upon this. And further, the 19% distant recurrent rate is also among the lowest that has ever been reported in the literature. I have 3 questions for the authors.

As well documented in the manuscript for the multivariate model, pathologic response rates, as you saw, that were greater than 95%, and an LVI or a perineural invasion with positive nodes were principally the factors that predict relapse-free survival. However, only 15% of the subjects studied actually achieved a pathologic response that was complete. An additional 19 patients, or 6% of the total, achieved a greater than 95% response but not complete. So in total, 21% of their total achieved a near-complete or complete response. That is very commendable.

But the question I have, Dr. Cohen, what measures are actually being implemented at Memorial, and now at the University of Kentucky, to potentially enhance these responses? Have you considered adding new, novel tumor induction mechanisms and drug sensitizers to your radiation?

Secondly, in our own studies at the University of Florida and the University of Alabama, where we have gone through various chemotherapeutic regimens, notably the change since the efforts of the NSABP to improve responses by the addition of leucovorin, as well as other international trials that confirm this, most medical oncologists currently use that combination postop.

But my question—and this also is in the manuscript that Dr. Cohen didn't have time to present—you have gone through a number of heterogeneous drug applications such as irinotecan and oxaliplatin in addition to 5-FU combinations. Would you extrapolate upon that and tell us if there are other drug applications that you are currently implementing?

Finally, you have well documented pathologic responses over 95%. In the absence of LVI or perineural invasion and absent lymph nodes or independent predictors, these findings do have prognostic implications for planning postoperative therapy of these patients. Are there select subgroups of these patients in whom you have had these types of complete or near-complete responses and are there patients that you would not consider using further postoperative therapy? And are you planning to place these regimens within prospective databases?

Dr. William G. Cance (Gainesville, Florida): As Dr. Bland has mentioned, they should be congratulated for such excellent results that they achieved in this very-high-risk group of patients with rectal cancer. They have an extraordinarily high rate of both local and distant control of the disease. There are several important strengths of this study.

First of all, is their uniform surgical approach based on sharp dissection of the mesorectum at the level of the endopelvic fascia in contrast to the manual extraction of the rectum that some authors described in years past. In addition, the ability for 71% of patients to have a sphincter-preserving operation is another outstanding accomplishment, with 52% having a coloanal anastomosis. I have 2 questions for the authors.

First, how can you transfer these principles to the surgical community as a whole? You have very specialized techniques to be able to achieve that level of sphincter preservation and that level of local control. How do we get these methods in the community so that others can apply similar techniques?

Second, in line with a question that Dr. Bland had asked, how will this influence your postoperative recommendations? Eighty-six percent of your patients received postoperative chemotherapy, but you allude in your paper that you may be able to exclude patients who need postop adjuvant therapy. Can you really be confident enough to exclude patients from further therapy based on their response?

Also, what recommendations do you have for postoperative therapy? As Dr. Bland has mentioned, there are a number of different options for the patient. There is often what I call the Indiana Jones approach to postoperative adjuvant care, making it up as you go, deciding this regimen or that regimen based on a variety of clinical and pathologic factors. Is there a standard approach postoperatively, and how will these results affect that approach?

Dr. Edward M. Copeland, III (Gainesville, Florida): I enjoyed your presentation since I have been convinced that neoadjuvant therapy for locally advanced rectal cancer results in an improved survival since we began to use this modality while I was at the M.D. Anderson Hospital about 1976. Try as we may, however, we have had a hard time convincing others of the efficacy of neoadjuvant versus adjuvant therapy until recently. We initially used neoadjuvant therapy to downstage large rectal cancers to be able to do sphincter-sparing procedures. The discovery that patients who downstaged to T0 had survivals in the 80 to 90% range was serendipitous. Likewise in our institution, we find that patients with locally advanced rectal cancer who downstage to T0 and have a low-lying lesion are candidates for transanal excision with virtually a zero local recurrence rate.

Do you agree that transanal excision can be utilized in these patients? Patients who are diagnosed initially with small T1 lesions are getting transanal excision quite commonly now and the RTOG trial, as I recall, of patients who had small T1 lesions and local excision had a greater than 10% local recurrence rate. So, should not we offer patients with T1 and T2 rectal lesions neoadjuvant therapy in an attempt to further reduce the size, afford them transanal excision and give them a local recurrence rate of hopefully close to zero? I realize the cost involved in neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy and the complication rate, yet if the results are so good for locally advanced rectal cancer, should we not consider extending it to patients with smaller lesions and expect to improve on survival possibly with a transanal excision and avoid a sphincter-preserving procedure requiring a complicated low anterior resection and possibly a protective ostomy?

So to summarize: transanal excision, is it heresy for these down-staged lesions, and why not extend neoadjuvant therapy to patients with T1 and T2 lesions?

Dr. Frederick L. Greene (Charlotte, North Carolina): Have we reached a point in the history of our treatment of rectal cancer where no new trials comparing preop and postop therapy should be done?

Dr. Alfred Cohen, one of the authors, has been very instrumental in wanting to standardize TME for surgeons. How close are we to actually having a standard for an operation?

Finally, one of the unwanted byproducts of radiation preop for rectal cancer is the reduction in the number of nodes that we find. We recommend in the AJCC that 12 to 15 nodes be examined. Have the authors seen a reduction in the number of nodes found in patients who are preoperatively radiated?

Dr. Courtney M. Townsend, Jr. (Galveston, Texas): Since everything we do has a risk and a finite incidence of complications, what is the incidence of an anastomotic leak, what is the incidence of an anastomotic leak requiring an reoperation and diversion, and what is the incidence of infection, both deep and superficial wound infection?

Dr. Nipun Merchant (Nashville, Tennessee): I would like to congratulate the authors on their dataset that can probably only be generated in 1 or 2 institutions in this country. I want to correlate these findings with the findings of the earlier paper on improved survival of complete responders to neoadjuvant therapy in esophageal cancer and compare it to our data. We similarly have found excellent survival rates, approaching 100% in patients that have complete or near-complete response to neoadjuvant therapy in rectal cancer and no improved survival in complete responders to neoadjuvant therapy in esophageal cancer. This difference in survival, I believe is related to 3 reasons.

One is that in rectal cancer we do have large trials of neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy showing survival benefit in these patients, whereas in esophageal cancer, the role of neoadjuvant therapy still remains controversial.

Two, when Heald proposed mesorectal excision as a surgical option, it was clear that improving local control of rectal cancer clearly was one of the mainstays of improving overall survival, whereas in esophageal cancer, the surgery that we do, transhiatal or transthoracic esophagectomy, doesn't show that by improving local control we improve survival in a similar manner, unless we consider a 3-field lymph-node dissection. Our data suggested that control with neoadjuvant therapy did not improve survival in complete responders due to their incidence of developing metastasis.

And thirdly, your results clearly show that adverse pathologic features are a negative prognostic factor for complete response and overall survival. And I think we would all agree that esophageal cancer clearly is a more aggressive cancer with more adverse pathologic features.

Those are 3 reasons, I believe, for the distinction between improved survival in rectal cancer versus esophageal cancer.

My question is, since we see such an improved response in overall survival with rectal cancer patients that have complete or near-complete response, I would like to echo what Dr. Bland asked, do we really need to have further adjuvant chemotherapy in these patients if they have such a good overall survival?

Dr. Jose G. Guillem (New York, New York): First, to address Dr. Bland's question on how to enhance the pathological response rate of rectal cancer to preoperative combined modality therapy, I would draw your attention to the recent results from a number of studies worldwide that have demonstrated the ability of chemotherapeutic regimens such as FOLFOX, FOLFIRI, and others to increase the pathological rate of rectal cancer response to upwards of 25 to 30% without increasing the rate of grade III toxicity. We at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center are currently exploring the ability of Erbitux and other modifiers aimed at enhancing the pathological complete response rate of rectal cancer to preoperative CMT. We, as others, are studying the mechanisms that govern rectal cancer response and resistance to preoperative CMT.

You asked the question, as did others, regarding the subset of pathological complete responders that may not need to go on to receive postoperative chemotherapy. I think this is a very intriguing question. We have wrestled with this as well and believe that any bulky, apparently aggressive rectal cancer that requires preoperative combined modality therapy should go on to receive postoperative systemic chemotherapy. This is based on the extrapolation of our experience with postoperative chemotherapy where a total of 6 cycles of chemotherapy are given. In the preoperative CMT protocol we give 2 cycles of chemotherapy preoperatively and 4 postoperatively. There is currently an ongoing EORTC study examining whether rectal cancer patients receiving preoperative CMT require postoperative chemotherapy.

Dr. Cance asked several questions. Importantly, how do we disseminate surgical technique which incorporates total mesorectal rectal excision to rectal cancer surgery into the community? I just want to point out that Dr. Alfred Cohen and others made a valiant effort through the means of the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group to establish an educational program aimed at training surgeons in the techniques of total mesorectal excision. I think that is one approach. Another approach is for all of us involved in the training of surgical residents to incorporate formal training sessions in total mesorectal excision within our surgical training programs. I believe that this is a long-term goal that will take place over several years to come but will ultimately result in an improvement in technique and certainly on outcome as well.

Dr. Copeland, I anticipated these questions from you, sir. I have read your work over the years and I think you have raised several very intriguing concepts worthy of further exploration. With regards to your first question, why not offer the small T0, T1 rectal cancer preoperative therapy? Putting aside the issues of cost and associated side effects, I think this is an intriguing question, which is being explored, in part, by the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group. With regards to exploring a local excision following completion of preoperative combined modality therapy of locally advanced rectal cancer, we recently published in the Annals of Surgery Oncology the risk of leaving disease behind in the mesorectum with this approach. We documented that in the mesorectum of rectal cancers that have undergone a pathological complete response to preoperative CMT, the rate of mesorectal lymph node involvement is about 7%, and 8% for a residual T1 lesion and approximately 20% for a T2 lesion. Therefore, although a local excision following preoperative combined modality therapy of locally advanced rectal cancer is an option, it is fraught with the likelihood of leaving residual mesorectal lymph node involvement behind. We recognize that this is nevertheless an approach which in certain circumstances may be the best option but one that requires that the patient be fully informed of the likelihood of residual disease in the mesorectum.

Dr. Greene asked the question of whether there is a need for any further studies comparing preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiation therapy. I think this question relates to the recent publication of the German Rectal Cancer Study which demonstrates, in a definitive manner, the improvement in local control but no improvement in overall survival with preoperative versus postoperative combined modality therapy. A concern I have with that study is that not all of the patients in the postoperative combined modality therapy group actually went on to receive postoperative therapy. This is not surprising for those of us that take care of these patients as we know that following surgery a number of them choose not to go on to receive postoperative systemic chemotherapy. Therefore, I think there is still the opportunity to explore this question further. With regards to your question on number of nodes, we have seen a reduction, as have others, in the number of lymph nodes following preoperative combined modality therapy.

Dr. Townsend asked the question about anastomotic leak and pelvic infection rates. We have, over the years, presented and published our results where we demonstrate an anastomotic leak rate of 4% in this patient population. I thank Dr. Merchant for his question, which I believe was addressed in response to Dr. Bland's.

Dr. Alfred M. Cohen (Lexington, Kentucky): I believe we have agreed that resective pancreatic cancer surgery should be done in specialty centers. I think that argument is over. I have been committed to trying to improve the quality of rectal cancer care in America at the general surgical level in the community. I now believe the data support adding rectal cancer to the cancers to be referred to specialty centers. This is a complicated issue that needs to be discussed openly by the surgical community.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute R01 82534-01, awarded to J.G.G.

Reprints: Jose G. Guillem, MD, MPH, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Avenue, Room C-1077, New York, NY 10021. E-mail: guillemj@mskcc.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Krook JE, Moertel CG, Gunderson LL, et al. Effective surgical adjuvant therapy for high-risk rectal carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:709–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prolongation of the disease-free interval in surgically treated rectal carcinoma: Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1465–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NIH consensus conference. Adjuvant therapy for patients with colon and rectal cancer. JAMA. 1990;264:1444–1450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grann A, Minsky BD, Cohen AM, et al. Preliminary results of preoperative 5-fluorouracil, low-dose leucovorin, and concurrent radiation therapy for clinically resectable T3 rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:515–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minsky BD, Cohen AM, Enker WE, et al. Preoperative 5-FU, low-dose leucovorin, and radiation therapy for locally advanced and unresectable rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37:289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valentini V, Coco C, Cellini N, et al. Preoperative chemoradiation for extraperitoneal T3 rectal cancer: acute toxicity, tumor response, and sphincter preservation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;40:1067–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Habr-Gama A, de Souza PM, Ribeiro U Jr, et al. Low rectal cancer: impact of radiation and chemotherapy on surgical treatment. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1087–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pucciarelli S, Friso ML, Toppan P, et al. Preoperative combined radiotherapy and chemotherapy for middle and lower rectal cancer: preliminary results. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosset JF, Magnin V, Maingon P, et al. Preoperative radiochemotherapy in rectal cancer: long-term results of a phase II trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;46:323–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grann A, Feng C, Wong D, et al. Preoperative combined modality therapy for clinically resectable uT3 rectal adenocarcinoma. Int J Radiation Oncol. 2001;49:987–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen NP, Sallah S, Karlsson U, et al. Combined preoperative chemotherapy and radiation for locally advanced rectal carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2000;23:442–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Onaitis MW, Noone RB, Hartwig M, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation for rectal cancer: analysis of clinical outcomes from a 13-year institutional experience. Ann Surg. 2001;233:778–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roh MPN, Wieand S, Colangelo L, et al. Phase III randomized trial of pre-operative versus postoperative multimodality therapy in patients with carcinoma of the rectum (NSABP R-03). Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2001; 490. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rullier E, Goffre B, Bonnel C, et al. Preoperative radiochemotherapy and sphincter-saving resection for T3 carcinomas of the lower third of the rectum. Ann Surg. 2001;234:633–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehta VK, Poen J, Ford J, et al. Radiotherapy, concomitant protracted-venous-infusion 5-fluorouracil, and surgery for ultrasound-staged T3 or T4 rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janjan NA, Khoo VS, Abbruzzese J, et al. Tumor downstaging and sphincter preservation with preoperative chemoradiation in locally advanced rectal cancer: the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;44:1027–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruo L, Tickoo S, Klimstra DS, et al. Long-term prognostic significance of extent of rectal cancer response to preoperative radiation and chemotherapy. Ann Surg. 2002;236:75–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Theodoropoulos G, Wise WE, Padmanabhan A, et al. T-level downstaging and complete pathologic response after preoperative chemoradiation for advanced rectal cancer result in decreased recurrence and improved disease-free survival. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:895–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ciabattoni A, Cavallaro A, Potenza AE, et al. Preoperative concomitant radiochemotherapy with a 5-fluorouracil plus folinic acid bolus in the combined treatment of locally advanced extraperitoneal rectal cancer: a long-term analysis on 27 patients. Tumori. 2003;89:157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mendenhall WM, Vauthey JN, Zlotecki RA, et al. Preoperative chemoradiation for locally advanced rectal adenocarcinoma: the University of Florida experience. Semin Surg Oncol. 2003;21:261–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sauer R, Becker H, Hohenberger W, et al. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1731–1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burke SJ, Percarpio BA, Knight DC, et al. Combined preoperative radiation and mitomycin/5-fluorouracil treatment for locally advanced rectal adenocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:164–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feliu J, Calvilio J, Escribano A, et al. Neoadjuvant therapy of rectal carcinoma with UFT-leucovorin plus radiotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:730–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bozzetti F, Andreola S, Baratti D, et al. Preoperative chemoradiation in patients with resectable rectal cancer: results on tumor response. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:444–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Medich D, McGinty J, Parda D, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy and radical surgery for locally advanced distal rectal adenocarcinoma: pathologic findings and clinical implications. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1123–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gunderson LL. Indications for and results of combined modality treatment of colorectal cancer. Acta Oncol. 1999;38:7–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia-Aguilar J, Hernandez de Anda E, Sirivongs P, et al. A pathologic complete response to preoperative chemoradiation is associated with lower local recurrence and improved survival in rectal cancer patients treated by mesorectal excision. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roh M, Petrelli N, Wieand S, et al. Phase III randomized trial of preoperative versus postoperative multimodality therapy in patients with carcinoma of the rectum (NSABP R-03). Proc ASCO. 2001;19:490. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skibber JMHP, Minsky BD. Cancer of the rectum. In: DeVita VTHS, Rosenberg SA, eds. Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2001:3235 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heald RJ, Moran BJ, Ryall RD, et al. Rectal cancer: the Basingstoke experience of total mesorectal excision, 1978–1997. Arch Surg. 1998;133:894–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Enker WE, Thaler HT, Cranor ML, et al. Total mesorectal excision in the operative treatment of carcinoma of the rectum. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181:335–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guillem JG, Puig-La Calle J Jr, Akhurst T, et al. Prospective assessment of primary rectal cancer response to preoperative radiation and chemotherapy using 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohiuddin M, Hayne M, Regine WF, et al. Prognostic significance of postchemoradiation stage following preoperative chemotherapy and radiation for advanced/recurrent rectal cancers. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48:1075–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moore HG, Gittleman AE, Minsky BD, et al. Rate of pathologic complete response with increased interval between preoperative combined modality therapy and rectal cancer resection. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:279–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitchell E, Winter K, Mohiuddin M, et al. Randomized phase II trial of preoperative combined modality chemoradiation for distal rectal cancer. Proc ASCO. 2004;22:254. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mehta V, Cho C, Ford JM, et al. Phase II trial of preoperative 3D conformal radiotherapy, protracted venous infusion 5-fluorouracil, and weekly CPT-11, followed by surgery for ultrasound-staged T3 rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55:132–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryan D, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, et al. A phase I/II study of preoperative oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil, and external beam radiation therapy in locally advanced rectal cancer: CALGB 89901. Proc ASCO. 2004;22:260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glynne-Jones R, Sebag-Montefiore D, McDonald A, et al. Preliminary phase II SOCRATES study results: capecitabine combined with oxaliplatin and preoperative radiation in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer. Proc ASCO. 2004;22:264. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodel C, Grabenbauer GG, Papadopoulos T, et al. Phase I/II trial of capecitabine, oxaliplatin, and radiation for rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2098–2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohiuddin M, Winter K, Mitchell E, et al. Results of RTOG-0012 randomized phase II study of neoadjuvant combined modality chemoradiation for distal rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60:s138–s139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DePaoli A, Chiara S, Luppi G, et al. A phase II study of capecitabine and pre-operative radiation therapy in resectable, locally advanced rectal cancer. Proc ASCO. 2004;22:3540. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dupuis O, Vie G, Lledo G, et al. Capecitabine chemoradiation in the preoperative treatment of patients with rectal adenocarcinomas: a phase II GERCOR trial. Proc ASCO. 2004;22:3538. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aschele C, Frison ML, Pucciarelli S, et al. A phase I-II study of weekly oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil, continuous infusion, and preoperative radiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer. Proc ASCO. 2002;21:132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tepper JE, O'Connell M, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Adjuvant therapy in rectal cancer: analysis of stage, sex, and local control: final report of intergroup 0114. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1744–1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moore HG, Shia J, Klimstra DS, et al. Expression of p27 in residual rectal cancer after preoperative chemoradiation predicts long-term outcome. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:955–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rau B, Sturm I, Lage H, et al. Dynamic expression profile of p21WAF1/CIP1 and Ki-67 predicts survival in rectal carcinoma treated with preoperative radiochemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3391–3401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guillem JG, Moore HG, Akhurst T, et al. Sequential preoperative fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography assessment of response to preoperative chemoradiation: a means for determining long-term outcomes of rectal cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chau I, Brown G, Tait PJ, et al. A multidisciplinary approach using twelve weeks of neoadjuvant capecitabine and oxaliplatin folllowed by synchronous chemoradiation (CRT) and total mesorectal excision (TME) for MRI defined poor risk rectal cancer. ASCO 2005 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium 2005.

- 50.Casado E, DeCastro J, Castelo B, et al. Phase II study of neoadjuvant treatment of rectal cancer with oxaliplatin, raltitrexed, and radiotherapy: 2004 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings (Post-Meeting Edition). J Clin Oncol. 2005;22:3764. [Google Scholar]