Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the outcome of aggressive conservative therapy in patients with esophageal perforation.

Summary Background Data:

The treatment of esophageal perforation remains controversial with a bias toward early primary repair, resection, and/or proximal diversion. This review evaluates an alternate approach with a bias toward aggressive drainage of fluid collections and frequent CT and gastographin UGI examinations to evaluate progress.

Methods:

From 1992 to 2004, 47 patients with esophageal perforation (10 proximal, 37 thoracic) were treated (18 patients early [<24 hours], 29 late). There were 31 male and 16 females (ages 18–90 years). The etiology was iatrogenic (25), spontaneous (14), trauma (3), dissecting thoracic aneurysm (3), and 1 each following a Stretta procedure and Blakemore tube placement.

Results:

Six of 10 cervical perforations underwent surgery (3 primary repair, 3 abscess drainage). Nine of 10 perforations healed at discharge. In 37 thoracic perforations, 2 underwent primary repair (1 iatrogenic, 1 spontaneous) and 4 underwent limited thoracotomy. Thirty-4 patients (4 cervical, 28 thoracic) underwent nonoperative treatment. Thirteen of the 14 patients with spontaneous perforation (thoracic) underwent initial nonoperative care. Overall mortality was 4.2% (2 of 47 patients). These deaths represent 2 of 37 thoracic perforations (5.4%). There were no deaths in the 34 patients treated nonoperatively. Esophageal healing occurred in 43 of 45 surviving patients (96%). Subsequent operations included colon interposition in 2, esophagectomy for malignancy in 3, and esophagectomy for benign stricture in 2.

Conclusions:

Aggressive treatment of sepsis and control of esophageal leaks leak lowers mortality and morbidity, allow esophageal healing, and avoid major surgery in most patients.

A single-institution retrospective review of 47 patients with esophageal perforations was performed. An aggressive, conservative nonoperative approach to treating sepsis and controlling esophageal leaks in the majority of patients resulted in an overall mortality of 4.2% and documented esophageal healing in 96% of discharged patients.

Esophageal perforation has traditionally been considered a catastrophic and often life-threatening event with mortality rates of 10% to 40% in general and even higher rates reported following spontaneous perforations in septic patients.1–5 Most surgeons and recent reviews have favored an aggressive surgical approach to this disorder, including primary surgical repair, aggressive surgical drainage, primary esophageal resection, or 2-stage resection and/or esophagostomy.5–8

Conservative treatment of esophageal perforation remains a controversial topic, although both early and more recent sporadic reports have documented the efficacy of nonoperative care, especially following perforation in nonseptic patients.9–12 The successful management of esophageal perforation by chest tube drainage without thoracotomy was described over 35 years ago in a series with a surprisingly large number of patients. Others, however, disagree with this approach, documenting mortality rates from 20% to 45% in patients undergoing this form of conservative or nonoperative care.2,3 A recent review, however, in what appears to be a prospective institutional bias, has documented 100% survival in a series of pediatric patients undergoing what the authors termed “aggressive conservative” nonoperative treatment.12 This present review evaluates a series of 47 patients with esophageal perforation treated at the University of Florida with a similar institutional bias. Our approach, based on early observations and experience, suggests that aggressive treatment of sepsis and plural fluid collections (with frequent radiologic confirmation) treats the primary cause of mortality and morbidity, avoids major surgery including esophageal resection, and allows the native esophagus to heal.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We reviewed the records of 47 patients with esophageal perforation admitted or evaluated at Shands Hospital at the University of Florida College of Medicine from 1992 through 2004. There were 31 males and 16 females with ages from 18 to 90 years (mean, 59 years). The etiology of the perforations was iatrogenic (endoscopy, dilation, instrumentation) in 25 cases, spontaneous perforation in 14, trauma in 3, dissecting thoracic aneurysm causing esophageal perforation in 3, and one each following a Stretta procedure and placement of a Blakemore tube. Overall, there were 10 documented perforations in the cervical esophagus and 37 perforations located in the thoracic esophagus. The time between perforation and presentation was estimated to be early (less than 24 hours) in 18 patients and late in 29 patients.

All patients with suspected or diagnosed esophageal perforation underwent initial chest x-ray and, when appropriate, placement of chest tubes and/or nasogastric tubes with the holes positioned in both the esophagus and upper stomach. All patients underwent an initial gastrografin UGI examination with contrast given orally or via the nasogastric tube. If clinically indicated, patients subsequently underwent CT examination of the chest and abdomen, usually within the first 6 to 24 hours. In recent years, especially in intubated patients, the first examination after the chest x-ray was a CT examination with oral contrast placed via the nasogastric tube. This test was then followed by a “real time” gastrografin UGI to ensure adequate drainage of the fluid resulting from the perforation. Follow-up CT and UGI radiologic examinations were usually performed within 2 days to document adequate chest drainage and evaluate the healing process. Repetitive radiologic studies were performed frequently, depending on the patient's fever and overall clinical condition. In appropriate cases and following the demonstration of undrained pleural fluid collections, radiologic percutaneous drains or chest tubes were placed using ultrasound at the bedside or under CT guidance in the radiology department. Radiology drainage was accomplished with standard “pigtail” catheters or Thal Quik (Cook) chest tubes using the standard Seldinger guidewire technique under CT guidance. This technique allows for accurate drainage, especially when placing posterior chest tubes behind the dome of the diaphragm. These tubes were placed in appropriate patients following confirmation of undrained fluid collections by CT examination.

In addition to the etiology and location of the perforations, patients were grouped according to surgical repair, surgical drainage, and nonoperative or conservative treatment. Measures of outcome include mortality, length of hospitalization, and esophageal healing.

RESULTS

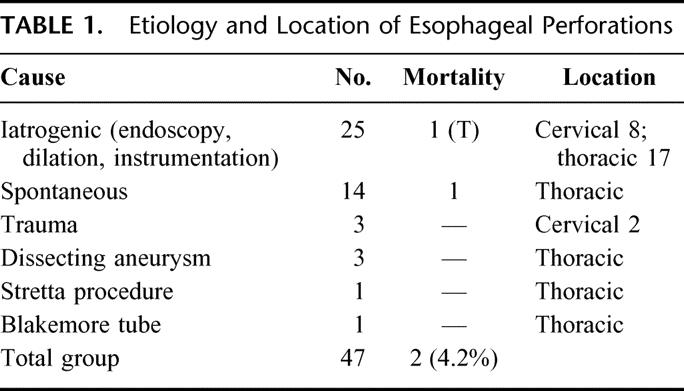

Table 1 summarizes the etiology and location of the esophageal perforations in 47 patients. Of the 25 patients (53%) with iatrogenic perforation, 8 were in the cervical area and 17 in the thoracic esophagus. All of the spontaneous perforations were in the thoracic area and 2 of the 3 trauma perforations were in the cervical esophagus.

TABLE 1. Etiology and Location of Esophageal Perforations

Treatment

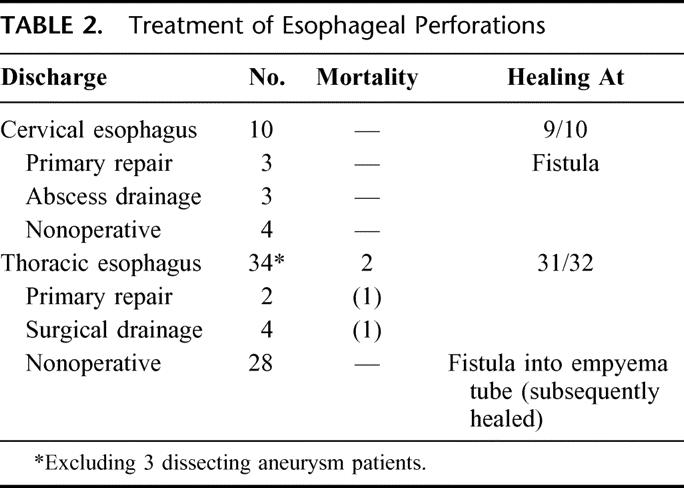

Excluding the 3 patients with dissecting aneurysms, 12 of the remaining 44 patients (27%) underwent either attempts at primary surgical repair or surgical drainage of fluid collections (Table 2). Six of 10 patients with cervical perforation underwent primary repair (in 3) and abscess drainage (in 3). Four patients underwent nonoperative treatment. All survived. Of the 34 thoracic perforations, 6 patients (16%) underwent either primary repair (in 2) or surgical chest drainage (in 4). Of the 2 patients undergoing primary repair, one had an early iatrogenic perforation and one was a spontaneous esophageal disruption who underwent surgery at the prior referring hospital. Both of these patients died and represent the only deaths in the entire group of 47 patients. Of the 4 (of 34) thoracic perforations undergoing surgical chest drainage, 1 was following an iatrogenic perforation and 3 were in the spontaneous group. Twenty-eight patients (83%) underwent nonoperative or conservative management. In the total 32 perforations treated nonoperatively, 28 were in the thoracic and 4 in the cervical esophagus.

TABLE 2. Treatment of Esophageal Perforations

Spontaneous Perforation

In the 14 patients with spontaneous perforation, 1 patient underwent early surgery while in septic shock and died (8%). The remaining 13 patients (92%) were initially treated aggressively with standard and radiologic chest tube drainage but nonoperatively. A total of 3 of these 13 patients underwent delayed surgical drainage. One patient underwent a thoracotomy for a contained perforation in the midesophagus that was causing persistent fevers and sepsis. Two other patients underwent a delayed but very limited thoracotomy through a small incision for better placement of right-angle chest tubes. The decision to operate was the concern that inadequate drainage might be causing persistent fever and sepsis. At surgery, the prior nonoperative drainage was considered to be completely adequate, but the surgeon was relieved to know that there were no fluid collections as the cause of persistent fevers. Retrospectively, the fevers were caused by pneumonia in both of these patients. Survival was 92%, and complete healing of the esophagus was documented in all 13 patients, after prolonged hospitalization.

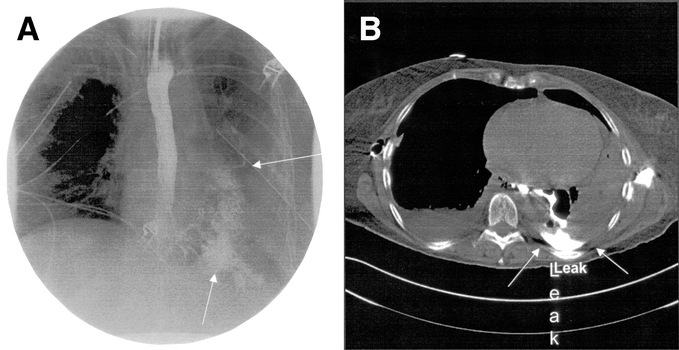

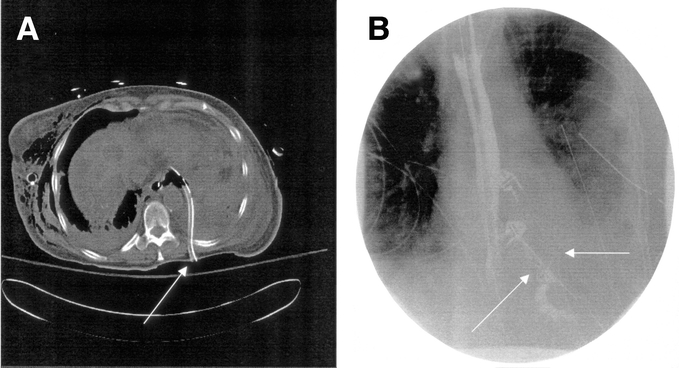

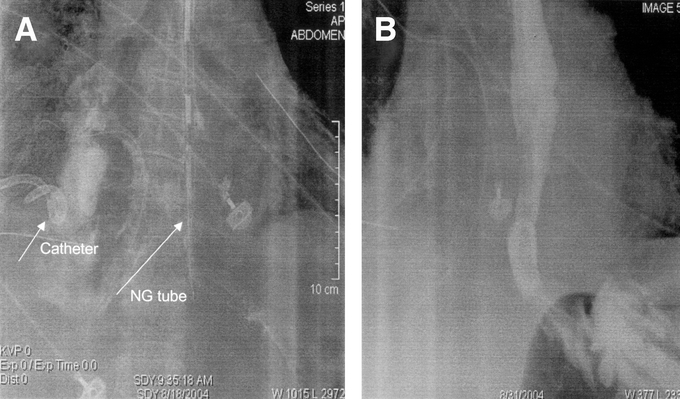

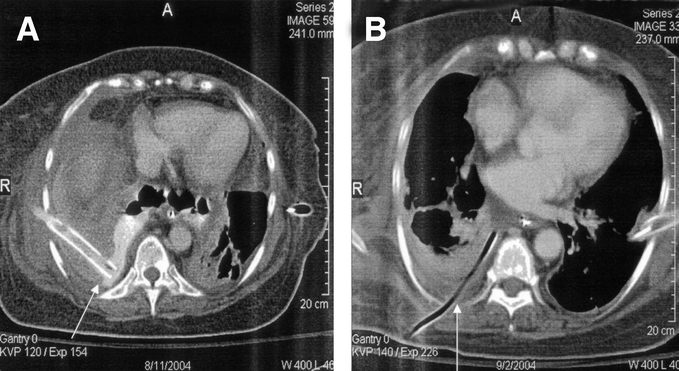

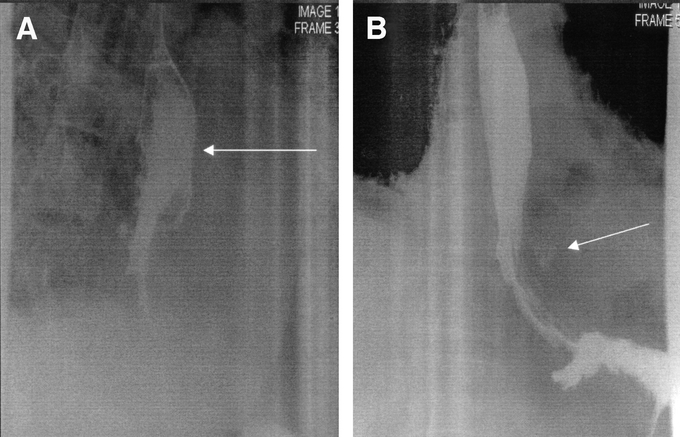

Figure 1 demonstrates an aggressive nonoperative approach to extensive contamination of the left chest following a spontaneous perforation. There are standard chest tubes in the right and left chest, extensive contamination by UGI contrast with the upper portion of the extravasated contrast draining into the chest tube. CT examination (Fig. 1B) demonstrates an undrained fluid collection despite adequate standard chest tube drainage. Figure 2A demonstrates the placement of a posterior Thal Quik chest tube under CT guidance. Subsequent gastrografin UGI (Fig. 2B) demonstrates almost complete diversion of the esophageal leak into the posterior chest tube. Figure 3A documents an extensive spontaneous perforation into the right chest. There are bilateral chest tubes and, on the right, the placement of a radiologic “pigtail” catheter to ensure more adequate drainage. Thirteen days later (Fig. 3B), there is complete healing of the esophageal perforation. Figure 4 documents the aggressive approach to posterior fluid collections following spontaneous esophageal perforation in the chest. A standard chest tube adequately drains the leak in Figure 4A, but a right-sided Thal Quik radiologic tube was placed in the posterior space (Fig. 4B) for adequate drainage of the perforation. Figure 5 demonstrates the patient with a contained midesophagus perforation. Figure 5B is the UGI following limited thoracotomy for drainage of the mediastinum demonstrating a small residual collection of contrast, which resolved over time.

FIGURE 1. A, An extensive esophageal leak partially drained into a left chest tube. B, CT examination demonstrates a residual posterior collection.

FIGURE 2. A posterior placed radiologic chest tube adequately drains the esophageal leak.

FIGURE 3. A, A radiologically placed “pigtail” catheter drains an extensive esophageal perforation. B, An esophogram demonstrates complete healing.

FIGURE 4. A standard chest tube (A) and a radiologically placed tube (B) drains posterior esophageal perforations.

FIGURE 5. A contained mediastinal perforation heals with a small residual collection following limited thoracotomy and drainage.

Mortality

Overall mortality in the entire group was 2 of 47 patients (4.2%). These 2 patients represent 5.8% of the 37 patients presenting with thoracic perforations (1 iatrogenic, 1 spontaneous) or 8% (1 of 14) of the patients with spontaneous perforation. One patient with spontaneous perforation underwent surgery at another hospital and was transferred to this institution in septic shock from their recovery room. He underwent a second operation and died within hours of surgery. This patient was considered a late arrival since the estimated time from perforation to his second operation was approximately 36 hours. A second patient (in 1993) developed sepsis and multisystem organ failure following an instrumental thoracic perforation and was treated within 24 hours of the event. Retrospectively, he had inadequate initial drainage. Following initial chest drainage and resuscitation, he underwent a thoracotomy for possible repair and better drainage of the esophageal leak. He subsequently died of multisystem organ failure within a week following surgery. There were no deaths in the 32 perforations undergoing nonoperative or conservative management, although (as described above) 4 more patients underwent thoracotomy for more adequate surgical chest drainage.

The 3 patients with dissecting thoracic aortic aneurysms were operated on for surgical repair of the dissection. Esophageal perforation was suspected in 2 patients. Two patients with esophageal tears underwent “patching” and extensive drainage. One healed primarily and the second healed following several weeks of adequate drainage. The third patient underwent esophageal exclusion by stapling and subsequently had a cervical esophagostomy. Following complete healing, this patient underwent a subsequent right colon interposition through the right anterior chest. All 3 patients survived aortic dissection and esophageal perforation.

Length of Stay

Total hospitalization in the entire group (excluding the death on day 1) ranged from 3 to 90 days with a mean hospitalization of 25.9 days. The mean hospitalization in the 25 patients with iatrogenic perforation was 14.8 days (range, 3–46 days). The 14 patients with spontaneous perforation had an average hospitalization of 41 days (range, 14–90 days excluding the one death).

Esophageal Healing

Excluding the early death and the dissecting aneurysm patient with esophageal exclusion, 43 of 45 patients had complete esophageal healing by discharge based on barium UGI examination. One patient was discharged with a small intermittent esophageal fistula following primary repair of the cervical esophagus. A second patient left the hospital with a small fistula into a chest empyema tube following iatrogenic esophageal perforation and chest tube drainage. Within 3 weeks, this fistula healed and the empyema tube was removed in clinic. Esophageal healing at the time of discharge was present in 100% of the 32 patients treated nonoperatively (thoracic 28, cervical 4). The fistulas occurred in surgically treated patients.

Chest Drainage

None of the 10 cervical perforations required chest tube drainage. Of the 37 remaining esophageal perforations, chest tubes were placed in a total of 28 patients. Many patients had multiple chest tubes placed either bilaterally or on one side. Nine patients with iatrogenic perforations were treated with antibiotics and nasogastric and/or nasoesophageal intubation. Radiologic “pigtail” catheters or Thal Quik tubes were placed in addition to standard chest tubes in 6 patients with spontaneous perforation and 1 patient with an iatrogenic injury.

Gastrostomy tubes were placed in a total of 8 patients (4 percutaneous and 4 operative with jejunostomy tubes). Three patients underwent separate placement of a jejunostomy tube during hospitalization. Most of the patients underwent parenteral hyperalimentation independent of the presence of G- or J-tubes.

Seventeen patients were considered to have respiratory distress syndrome requiring either prolonged intubation and/or tracheostomy placement. Most of the spontaneous perforations were in this group. Eight patients were considered to have significant pneumonia necessitating frequent CT examinations to rule out recurrent fluid collections as the source of the intermittent fevers. All of these cases except one (death) survived pneumonia and respiratory distress. Following discharge, subsequent early operations included colon interposition in 2, esophagectomy for malignancy in 3, and esophagectomy for benign stricture in 2. An additional 4 patients have undergone at least one cautious esophageal dilation for a symptomatic stricture, although long-term results are pending.

DISCUSSION

Most thoracic esophageal perforations, especially spontaneous disruptions in ill or septic patients, are treated surgically with surgeons preferring primary surgical repair, surgical drainage, or esophageal resection. Early reviews,9–11 however, have documented the successful nonoperative or conservative treatment of not only iatrogenic perforations but in those patients with Boerhaave syndrome or spontaneous perforation.13,14 The major issues concerning the type of treatment of esophageal perforation as discussed by Cameron et al9 are whether mediastinal contamination and/or free pleural fluid can be contained by chest tube drainage. These authors state that when the disruption is well drained, nonoperative management and antibiotics can be the treatment of choice. Mengoli and Klassen10 documented this form of treatment in a series of 21 patients with thoracic esophageal perforations and pleural contamination. Eighteen patients were managed without thoracotomy with only a 6% mortality.10 Also in these early years, Lyons et al compared results of the treatment of 18 patients with esophageal perforation with 11 patients managed without thoracotomy.11 Mortality was 38% in the surgically treated group and only 9% in the conservatively managed patients.11 As discussed by Cameron et al,9 most of these patients did not have simply a contained perforation and chest tube drainage was used for free pleural fluid.9–11 In a more recent review, Martinez et al reported successful “aggressive conservative” treatment in a series of iatrogenic perforations with 100% survival.12 These authors suggested that perforations and pleural contamination, once controlled by adequate drainage, simply become an esophagocutaneous fistula (via the chest tube) and will heal similar to most gastrointestinal fistulas. We tend to agree with this hypothesis, and it has become the basis for our own institutional bias toward aggressive but nonoperative treatment of thoracic perforations.

In the present series of 34 patients with a perforated thoracic esophagus (excluding the 3 dissecting aneurysms), there were 2 deaths in the 6 patients undergoing an operative procedure. Overall, however, primary healing of the esophagus occurred in 31 of 32 patients. There were no deaths and 100% survival in the patients treated nonoperatively. It is our opinion that the radiologists play an extremely important role in the success of this type of treatment. Frequent UGI and CT examinations accurately and adequately document the containment of esophageal leaks into either standard or percutaneously placed radiologic tubes. A very rapid radiologic response following esophageal perforation is an important factor in overall survival. It is true, however, that 4 of these patients underwent surgery (limited thoracotomy in 2) to ensure adequate drainage, and we think that this approach guarantees containment of the leaks following nonoperative treatment, even if some patients need replacement of the chest tubes.

Unfortunately, recent series have not been as enthusiastic as we are concerning this type of therapy. The original criteria suggested by Cameron et al.9 has been modified to a more stringent approach to esophageal perforation by Altorjay et al,11 who recommended nonoperative treatment only for intramural perforations, and Kiernan et al,1 who suggested that conservative therapy be reserved for “microperforations” only with no ongoing leaks. Amir et al initially treated 21 patients nonoperatively but reported that delayed surgery was required in 9 patients to adequately treat the perforation.16 An even higher mortality of 45% was reported by Okten et al following conservative therapy in a series of patients in which the authors' overall recommendaton was primary repair or resection.2 Advocates of more aggressive treatment report favorable mortality rates of 13% and 12% following esophageal resection for perforations. Salo et al compared the 13% mortality in the resection group against 68% in their nonresected group.7 Orringer and Stirling, however, reported a one-stage esophageal resection when there was intrinsic esophageal disease and distal obstruction in 24 patients with an overall 88% survival.8 Fortunately, in our study we had neither the inclination nor the need for major esophageal resection. Even in the most seriously ill of our patients (the 14 spontaneous perforations), rapid and aggressive standard and percutaneous techniques contained the esophageal leaks and plural fluid. It is true that 1 patient with a contained mediastinal leak needed a thoracotomy for more adequate drainage, but the other 2 patients had replacement of chest tubes only through a small thoracotomy incision. Overall mortality in this group was 7% (1 of 14 patients).

In summary, there was an overall survival of 96% in a total group of 47 patients presenting with esophageal perforations. Of the 32 patients treated nonoperatively, there was 100% survival. Esophageal healing occurred in 43 of 45 (96%) patients. Even in the patients with spontaneous esophageal disruption, 13 of 14 patients survived (93%).

CONCLUSION

We present our experience with 47 patients with esophageal perforation, confirming the success of this “aggressive conservative” approach to iatrogenic and spontaneous esophageal disruptions. In most patients, esophageal leaks and free pleural fluid can adequately be contained. We think that this approach has eliminated the primary cause of mortality and morbidity, avoided major surgery and, in most cases, allowed the esophagus to heal normally.

Discussions

Dr. Alan S. Livingstone (Miami, Florida): Dr. Vogel has devoted his whole academic career to studying complex problems of the foregut, and this is another example of looking at a challenging problem and approaching it differently than many other surgeons would. Indeed, there are few scenarios more challenging than the surgical management of perforated esophagus.

This is a retrospective paper of 47 patients treated over a period of 12 years. It is seductively appealing to propose treating all of these very difficult parents without having to perform emergency surgery on them. However, I think that considering how strongly other authors advocate early intervention on these patients, a prospective randomized trial comparing this aggressive conservative management with surgical intervention will be needed to compare the relative merits of the 2 approaches.

The title of the paper implies that this is a nonsurgical series, but a careful reading of the paper shows that 15 of 47 patients were initially treated surgically. Indeed, even the remaining patients were treated following the fundamental surgical principle of wide drainage; it was just done by the interventional radiologist, and that is the critically important point. Dr. Vogel emphasizes the concept of trying to save the native esophagus, and I would absolutely concur with this approach.

The Martinez paper12 is used as evidence of excellent outcomes with aggressive conservative management. I think the experience is not necessarily translatable to the adult as this is a pediatric series. These patients are almost always perforated during rigid endoscopy and dilation of strictures. These perforations are witnessed, detected early, treated with antibiotics, and tend not to be as catastrophic as many of the spontaneous perforations seen in adults.

This series is actually a heterogeneous group. I wonder if the approach proposed by Dr. Vogel is applicable across the whole spectrum of esophageal injury. I tend to stratify the perforations into cervical and thoracic, and then iatrogenic and “others.”

You have proven perfectly well that the iatrogenic patients can be managed conservatively. It is interesting to me that in the cervical perforations, 6 of 10 were treated surgically. Most of them can actually be managed conservatively.

The thoracic perforations are the most problematic ones. As in children, the iatrogenic perforations can almost always be managed conservatively. In fact, as you pointed out, 9 of 17 of your patients did not even have to have a chest tube inserted and were just treated with antibiotics.

The other cases are a little bit more challenging. The 3 aortic dissection cases were all treated surgically. How you managed to get all of them to live is beyond me, and I congratulate you for that. There was only one traumatic thoracic perforation, and it was treated nonoperatively. As we know, most penetrating traumatic esophageal perforations have associated injuries that dictate emergent exploration, so I presume that this patient had a blunt blowout.

The remaining cases are the ones I would like to ask you a few questions about. When you were treating the perforated esophageal cancer patients, my personal bias has always been to apply oncologic principles in an effort to try to prevent local implantation or dissemination. We would ordinarily operate on those patients and usually do a transhiatal esophagectomy as most of them are distal lesions. If they were unstable, I would not reconstruct them at the initial operation.

The final comment relates to whether or not, in these critically ill patients with spontaneous perforations, you have proven your point about the value of conservative therapy. The median duration of hospitalization was 41 days with prolonged intubation, which is a very long time, compared to some surgical series.

I congratulate you on your series. No matter what else can be said, you managed to keep most of these patients alive and get them through a very difficult problem.

Dr. Joseph LoCicero, III (Mobile, Alabama): I would like to bring up a stimulating point here at the end. I think it is time to throw away the gastrografin bottle. All of the studies that have been done with gastrografin in the chest show a blurred picture. They really don't show the perforation very well. The only thing we see is a gigantic puddle. The reason for using gastrografin in the chest is because of the studies that were done in the colon where barium was a problem. There really are no data demonstrating that barium is an issue in the chest.

We have had this discussion multiple times with the thoracic radiologists, and we have finally come to this conclusion. Use the contrast that you are going to use for a CT scan. It is thicker, it shows the perforation well on a regular swallow study, and if you need to, you go right to the CT scan.

Dr. Alexander S. Rosemurgy, II (Tampa, Florida): I think this is a “hands-on-study” by a “hands-on” surgeon with great clinical experience. As the old adage goes, bad judgment leads to experience, and experience leads to good judgment. So I am curious as to how this all unfolded to lead to this approach. I have a couple of thoughts.

First, the word “conservative” in the title is probably a misnomer. For me, the “conservative” management of a surgical problem is an operation. For example, the conservative management of a ruptured spleen is splenectomy. So I try not to confuse “conservative” with “nonoperative.”

Second, 10 of the 47 patients, as has been pointed out, had cervical perforations, which is a different problem than a thoracic perforation.

Third, while it really doesn't change the tenor of this paper, it is notable that in this study of 37 patients with thoracic perforations, 29% of the patients presented late. There are notable differences between patients that present early versus late, as the latter have already passed the test of time.

Furthermore, I am curious if there are patients that are handled in a different manner than proposed by your paper because they are too sick to be handled through this algorithm. For example, simply stated, are other patients at your institution handled differently?

The issue of cost has been brought up, and that is of some concern. Obviously, cost translates into length of stay and hospital ICU days. Then, as well, there are issues of functional outcome. It would seem reasonable that some of these perforations will heal, but they will heal with strictures and poor long-term functional outcomes.

I am also curious if there is a limit to what can be handled nonoperatively. For example, if you alluded to healing of a basically intact esophagus, but what about a basically “notintact” esophagus?

In summary, I think that there are 3 important interventions in patients that have had esophageal perforations: 1) we need to prevent ongoing soilage; 2) we need to provide debridement of devitalized tissue; and 3) we need wide drainage. Obviously, this approach provides wide drainage, but it belies the importance of preventing ongoing soilage and it obviously avoids any debridement.

Having said that, I have questions about a couple of patients. A patient presents with an acute perforation of the distal esophagus. Contrast extravasation into the peritoneal cavity is seen with esophagogram. Does that patient get handled with selective management you propose? Would it make a difference if a patient had crepitance in the neck? Thank you.

Dr. Stephen B. Vogel (Gainesville, Florida): I would like to thank Dr. Livingstone and Dr. Rosemurgy for reviewing the manuscript and discussing this difficult topic. We appreciate the fact that this has always been a controversial and emotional topic among general surgeons.

Before I get to the specific questions, I would like to say that, although this has been a retrospective review, our prospective approach beginning many years ago was similar to other general surgery principles, including good drainage for potentially infected fluid collections thereby preventing or treating sepsis early.

Concerning cervical perforations, we would agree with Dr. Livingstone that most surgeons would not necessarily operate for these perforations. Several of these patients were treated by the ENT service, but overall only 3 of the 10 cervical perforation patients underwent primary repair. Three others, as mentioned, underwent abscess drainage when these were demonstrated by CT. Four patients underwent nonoperative treatment. As to whether a cervical perforation should be operated on or not, we remain fairly neutral to this decision-making process. In general, a cervical exploration for either primary repair or abscess drainage is considered a simple operation compared to other major approaches to intrathoracic perforations.

Concerning the question of “raging mediastinitis,” I can't say that we really identified that process since we operated on so few patients. The most seriously ill patients, however, were those that had a spontaneous intrathoracic perforation and many of these remained febrile for quite a few days even after adequate drainage. There were several patients with contained mediastinal perforation based on CT evaluation and these were perhaps the most ill and septic over a period of days. One patient as mentioned in the presentation underwent delayed thoracotomy for mediastinal drainage after approximately 5 or 6 days of ongoing fever and signs of sepsis. All of the other patients seemed to respond quite well to drainage, antibiotics and, perhaps most importantly, naso-esophageal drainage via the nasogastric tube.

The question of a perforated malignancy has always been problematic to us. We appreciate that the historical approach, and perhaps the “Board answer” might be immediate esophagectomy. On the other hand, since I have performed most of the esophagectomies at our institution, I haven't been able to reconcile performing a major procedure on a sick and potentially septic patient. Although transhiatal esophagectomy can easily be performed immediately after a perforation, I have never been sure as to whether contamination by malignant cells occurring in the first hours after a perforation is any different than allowing the perforation to heal and operating on the patient electively. I have performed these procedures following the perforation, and they are only marginally more difficult in terms of dissecting the tumor from the mediastinum.

As to the question concerning when this approach started, it began in the late 1970s when we realized that taking several patients to the operating room in a septic condition with respiratory distress syndrome led to less than satisfactory results. My partner at the time was the chairman, Dr. Woodward, and both of us felt that controlling the sepsis and draining the fluid collections might be the better way to go at that time.

As to the question concerning the oral contrast medium that we use, after years of performing sequential gastrografin upper GI examinations either followed by or preceding the CT examinations, our radiologists suggested that we use gastrovue contrast for the real-time upper GI examination and immediately after this procedure obtain a CT examination. At the present time, this is our radiologists' recommendation for the initial studies and for follow-up examinations. I might add also that we have never had any problems with either our critical care team or the radiologists with transporting intubated patients to x-ray for examination any time of the day or night. Certainly, our ability to perform these procedures as well as radiologic drainage of intrathoracic fluid collections could not be done without the assistance and enthusiasm of our radiologists.

Overall, our total experience has allowed us to see things somewhat differently than we imagined years ago. Early on, we realized that, after adequate drainage of an esophageal perforation and treatment of the septic condition, we were then left with what appeared to be an esophago-cutaneous fistula via the chest tube or percutaneous catheter. In a way this is very similar to and mimics what we see following drainage of a contained intra-abdominal abscess. The advantage in the esophagus compared to the intra-abdominal GI tract is that there is no ongoing contamination once the nasogastric tube is placed in the esophagus. The second benefit is that we now are assured that most, if not all, esophageal perforations will heal with “tincture of time” and adequate drainage of the perforation.

As a general rule, the “aggressive” part of the treatment, especially when confronted with patients with spontaneous perforations being transferred to our hospital late in the evening or the middle of the night, is the placement of the chest tubes, obtaining the gastrovue and CT examinations, and if necessary, placement of further percutaneous chest tubes within hours of stabilization. We have been very enthusiastic about this approach and, as per our results, we think we have saved far more lives by utilizing this technique than had all of the patients undergone surgery. We would hope that other surgeons confronted with these situations will see the efficacy of initially treating the septic condition and adequately draining the fluid collection. This may obviate the necessity of major operative procedures, cervical diversion, or other procedures in these patients.

Footnotes

Reprints: Stephen B. Vogel, MD, Department of Surgery, Health Science Center, P.O. Box 100286, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32610. E-mail: stevebv@aol.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kiernan PD, Sheridan MJ, Elster E, et al. Thoracic esophageal perforations. South Med J. 2003;96:158–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okten I, Cangir AK, Ozdemir N, et al. Management of esophageal perforation. Surg Today. 2001;31:36–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta NM, Kaman L. Personal management of 57 consecutive patients with esophageal perforation. Am J Surg. 2004;187:58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jougon J, McBride T, Delcambre F, et al. Primary esophageal repair for Boerhaave's syndrome whatever the free interval between perforation and treatment. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;25:475–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zumbro GL, Anstadt MP, Mawulawde K, et al. Surgical management of esophageal perforation: role of esophageal conservation in delayed perforation. Am Surg. 2002;68:36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kollmar O, Lindemann W, Richter S, et al. Boerhaave's syndrome: primary repair vs. esophageal resection: case reports and meta-analysis of the literature. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:726–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salo JA, Isolauri JO, Heikkila LJ, et al. Management of delayed esophageal perforation with mediastinal sepsis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;106:1088–1089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orringer MB, Stirling MC. Esophagectomy for esophageal disruption. Ann Thorac Surg. 1990;49:35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cameron JL, Kieffer RF, Hendrix TR, et al. Selective nonoperative management of contained intrathoracic esophageal disruptions. Ann Thorac Surg. 1978;27:404–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mengoli LR, Klassen KP. Conservative management of esophageal perforation. Arch Surg. 1965;91:238. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyons WS, Seremetis MG, deGuzman VC, et al. Ruptures and perforations of the esophagus: the case for conservative supportive management. Ann Thorac Surg. 1978;25:346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martinez L, Rivas S, Hernandez F, et al. Aggressive conservative treatment of esophageal perforations in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:685–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larrieu AJ, Kieffer R. Boerhaave syndrome: report of a case treated non-operatively. Ann Surg. 1975;181:452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown RH, Cohne PS. Nonsurgical management of spontaneous esophageal perforation. JAMA. 1978;240:140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deleted in proof.

- 16.Amir AI, van Dullemen H, Plukker JT. Selective approach in the treatment of esophageal perforations. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:418–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]