Abstract

A set of 22 551 unique human NotI flanking sequences (16.2 Mb) was generated. More than 40% of the set had regions with significant similarity to known proteins and expressed sequences. The data demonstrate that regions flanking NotI sites are less likely to form nucleosomes efficiently and resemble promoter regions. The draft human genome sequence contained 55.7% of the NotI flanking sequences, Celera’s database contained matches to 57.2% of the clones and all public databases (including non-human and previously sequenced NotI flanks) matched 89.2% of the NotI flanking sequences (identity ≥90% over at least 50 bp, data from December 2001). The data suggest that the shotgun sequencing approach used to generate the draft human genome sequence resulted in a bias against cloning and sequencing of NotI flanks. A rough estimation (based primarily on chromosomes 21 and 22) is that the human genome contains 15 000–20 000 NotI sites, of which 6000–9000 are unmethylated in any particular cell. The results of the study suggest that the existing tools for computational determination of CpG islands fail to identify a significant fraction of functional CpG islands, and unmethylated DNA stretches with a high frequency of CpG dinucleotides can be found even in regions with low CG content.

INTRODUCTION

Draft sequences of the human genome were recently reported (1,2). Much work remains to be done to produce a complete finished sequence and progress can be best assured by a diversity of approaches (1). At present, one of the principal goals for genome research is a careful and systematic validation of the assembled sequence (1–4). In this respect it becomes critically important to develop and to apply strategies capable of fulfilling this crucial aim. These strategies should exploit approaches independent of those used to generate the original genome sequence. Short sequences flanking the rare restriction sites, for instance NotI, might serve as a tool for validation of human genome structure.

NotI linking clones contain pairs of sequences flanking a single NotI recognition site, while NotI jumping clones contain DNA sequences spanning between neighboring NotI restriction sites. Such clones were shown to be tightly associated with CpG islands and genes (5,6). The use of NotI linking and jumping clones as framework markers was proposed to define the structure of large regions of human chromosomes (7–13). To achieve this goal, simplified procedures for the construction of NotI jumping and NotI linking libraries were developed and a number of chromosome 3-specific and other chromosome-specific and total human NotI linking libraries were prepared (7–15).

One thousand human chromosome 3-specific NotI linking clones were partially sequenced (6). Among these, 249 unique clones were identified and 152 were carefully analyzed. To localize these clones, PCR, Southern hybridization, pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and two- or three-color fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) were applied. In many cases, chromosome jumping was successfully used to resolve ambiguous mapping (6,13). This NotI map was compared to the chromosome 3 map, based on yeast artificial chromosome clones and radiation hybrids (14), and significant differences in several chromosome 3 regions were noticed. Importantly, these differences included a 3p14–p22 region with homozygous deletions and most likely containing tumor suppressor genes (6). These data supported earlier notions (13,15) that a NotI physical map can be more informative than genetic or radiation hybrid maps.

To enable a direct assessment of the value of NotI clones in genome research, high-density grids with 50 000 NotI linking clones derived from six representative NotI linking and three NotI jumping libraries were constructed. Altogether, these libraries contained nearly 100 times the total estimated number of NotI sites in the human genome. Sequencing of 20 000 NotI clones was projected to provide information linked to 10–20% of all human genes (9) and may help in the identification of new genes. Before starting a large-scale project, a pilot study to validate the proposed strategy was performed (16). In that work 3265 unique NotI flanking sequences were generated. Analysis of sequences demonstrated that ∼50% of these clones displayed significant similarity to protein and cDNA sequences. Among these unique sequences, 1868 (57.2%) were novel sequences, not present in the EMBL or expressed sequence tag (EST) databases (similarity ≤90% over 50 bp). The work also showed tight, specific association of NotI sites with the first exons of genes. From that NotI resource several new genes have been identified, isolated and mapped (17–22).

As the pilot experiments confirmed expectations, the sequencing of NotI clones was continued and ∼22 500 unique NotI sequences were generated. This work provides the initial analysis of these data.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General methods

Common molecular and microbiological methods were performed according to standard procedures (23). Plasmid DNA was isolated using a Biorobot 9600 (Qiagen) with REAL-prep kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing gels were run on ABI 377 automated sequencers (PE Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Sequencing was done as described previously (16).

NotI libraries, clone names and accession numbers

Construction of NotI linking and jumping libraries was as described (10,16). The CBMI-Ral-Sto cell line, selected for its unusually low level of methylation, was established by immortalization of human B cells with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) strain B95-8 (24). Thus, the DNA isolated from this cell line contained EBV sequences. The nomenclature for the NotI linking libraries and clones used in this study is the same as in a previous work (16).

The EMBL/GenBank accession numbers for the NotI sequences used in this work are AQ936570–AQ939834 and AJ322533–AJ343893.

Sequence analysis

The analysis of sequences was performed at the Karolinska Institute Sequence Analysis Center (kisac.cgr.ki.se), using local versions of programs and public databases.

Protein and nucleotide similarity searches were performed with BLAST 2.0 (25,26). The high scoring segment pairs report cut-off (BLAST parameter –b) was restricted to 100 for protein and to 50 for nucleotide databases. The statistical significance threshold (BLAST parameter –e) was default (–e = 10) for the TREMBL (Translated EMBL) and SWISSPROT databases and for other databases searches was set to: EMBL and EST, –e = 1.E–10; Unigene (non-redundant set of gene-oriented clusters database), –e = 0.1; RefSeq (Reference Sequences) nucleotide and protein databases, –e = 0.001.

MSPcrunch (version 2.4) was used to filter the BLAST program for selection of significant matches (27). This filtering ensures that domains with weak but significant hits will not be missed due to other higher scoring domains and ‘junk’ matches with biased composition are eliminated. Similarity data was sorted with MSPcrunch using default parameters (–B = 0.8 and 5, –C upper = 75, –C lower = 35 for protein alignments; –B = 0.8 and 5, –C upper = 140, –C lower = 90 for nucleotide alignments) and stringent (–B = 0.85 and 0, –C upper = 85, –C lower = 45 for protein alignments; –B 0.85 and 0, –C upper = 150, –C lower = 100 for nucleotide alignments).

Default parameters were used to search the RefSeq, EST and Unigene databases. Stringent parameters were used for the EMBL, HTGS (High Throughput Genomic Sequences) and SWISSPROT + TREMBL databases. Empirical testing suggests that these parameters are effective in removing false matches (27).

All short, simple and low complexity repeats were excluded from the analysis using RepeatMasker with the default minimum Smith-Waterman score of 225 (http://repeatmasker.genome.washington.edu).

We used the RefSeq database release of December 2001 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/LocusLink/refseq.html) with 14 300 human gene entries.

Initial searches with NotI sequences were performed in June 2000 (EMBL database release 59, SWISSPROT database release 38, TREMBL database release 14) and December 2000 (EMBL database release 65, SWISSPROT database release 38, TREMBL database release 15). Additional comparisons were done in March 2001 against the draft of the human genome sequence (1,2). NotI sequences that failed to match to any of the above databases were searched again in June and December 2001 (EMBL database releases 67 and 69, SWISSPROT database releases 39 and 40, TREMBL database releases 17 and 19 and the draft human genome sequence).

Construction of a NotI sequence database from the human genome sequencing data

In order to focus on NotI restriction sites within the large body of data from the human genome sequencing project, a NotI sequence database from the human genome sequencing data was constructed. Sequences (1 kb) extending out from NotI sites were taken from the HTGS database for subsequent analysis. We allowed for one mismatch to the NotI target sequence to ensure maximal coverage of NotI sites.

The analysis of 1 kb NotI flanking sequences for nucleosome formation potential was performed as described (28).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

General characteristics of the NotI flanking sequences

In this study 23 574 sequences flanking NotI sites were generated. Among them, 217 (0.9%) matched genomic sequences for Escherichia coli, 296 (1.3%) were from Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) and 131 (0.6%) sequences were most probably of Pseudomonas sp. origin. Escherichia coli DNA contaminated the vector preparation and EBV B95-8 was present in the human genomic DNA (see Materials and Methods). The level of identity in these matches was at least 90% over 100 bp. Therefore, 22 930 sequences were classified as human. However, Pseudomonas sp.-related sequences may be a real component of the human genome, as previously suggested (1). A few sequences related to Synechocystis sp., Bacillus sp. and Streptomyces sp. were also detected. Therefore, these data support the suggestion that the human genome contains sequences related to different bacterial species (1). The origin of such sequences is unclear (1,29).

Within the human subset, 379 (1.7%) redundant sequences were identified. Redundant sequences were defined as sequences sharing at least 99% identity over 360 bp of their length (this safeguard was used so as not to remove unique sequences that nevertheless have partial overlap due to common repeats or localization close to NotI, BamHI or EcoRI restriction sites).

When the stringency for the identification of redundant sequences was reduced to 93% then only 15 702 sequences were classified as unique. However, we have previously found that NotI flanking sequences originating from different chromosomes can have 95–100% identity over >700 bp (6,16,22). Therefore, to exclude the possibility of removing unique flanks we defined the unique human subset to include the 22 551 sequences identified with more stringent criteria.

The sequence set covered a total of 16 213 509 bp with an average sequence length of 720 bp. After sequencing, 0.3% (55 144 cases) of all nucleotides were reported as ambiguous (N). Comparisons between multiple sequencing reactions of the same clones indicated a sequencing accuracy of at least 98.5% over the first 160 bp. The sequence accuracy varied among clones with a negative relation to overall CG content and fluctuated along the sequence length. The achieved sequence fidelity was appropriate for the study as a short length cut-off for matching sequences was used (see Materials and Methods).

The repeat masking procedure (see Materials and Methods) identified 7227 (32.0%) of the NotI sequences as containing known repeats (Table 1). The repeats comprise 1 066 657 bp or 6.6% of the 16.2 Mb total and 20% of the total sequence from the repeat-containing clones. Comparison of these data with the draft human genome sequence revealed striking differences. All interspersed repeats occupied 44.8% of the total human genome sequence but only 4.7% of the NotI flanks. Alu repeats were present 6.6 times less frequently in the NotI sequences, while for LINE repeats this difference was almost 14-fold. Simple sequence repeats were also deficient in the vicinity of NotI sites (0.54 versus 3%). On the other hand, the youngest human LINE1 elements (L1Hs) represented 0.5% of all LINE elements in NotI flanking sequences compared to 0.1% in the total human genome. L1Hs are the only inter spersed repeats that still actively transpose in the human genome (1). One possibility is that NotI flanking sequences are located in actively transcribed chromosomal regions and therefore are available for transposition. However, sequences surrounding NotI sites may not tolerate such insertions and thus the older inserted elements were eliminated during evolution.

Table 1. Summary of repeat content.

| Repeats | Number of elements | Length occupied (bp) | Percentage of sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALUs | 1247 | 259 527 | 1.60 |

| LINEs | 958 | 237 398 | 1.46 |

| Others | 1581 | 260 605 | 1.61 |

| Total interspersed repeats | 757 530 | 4.67 | |

| Simple repeats | 1523 | 88 240 | 0.54 |

| Low complexity repeats | 4310 | 203 219 | 1.25 |

| Total | 1 066 657 | 6.58 |

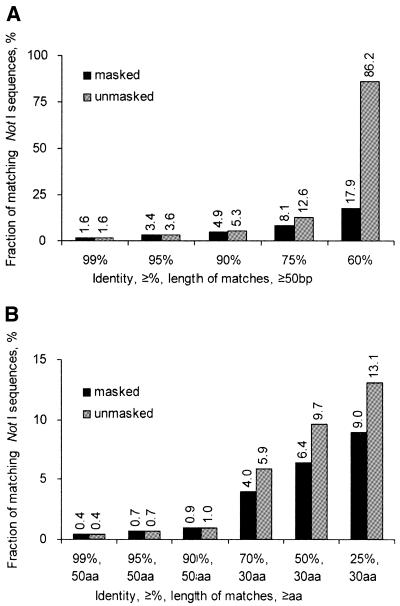

To estimate the influence of repeats on the sequence analysis results, we compared masked and unmasked NotI sequences with the RefSeq nucleotide and protein databases (Fig. 1). The presence of repeats in the NotI flanking sequences does not impact on the analysis results with stringent comparison criteria. In fact, only under the relaxed stringency (e.g. 60% similarity over 50 bp) do repeats influence the results dramatically. All further analyses utilized masked sequences.

Figure 1.

Similarity between unmasked/masked NotI sequences and (A) the RefSeq nucleotide database, (B) the RefSeq protein database.

Using NotI sequences to verify the assembled human genome sequences

Several data collections have been compared against the human genome (euchromatic) assembly to estimate sequence coverage, including the RefSeq cDNA database, the set of STS markers, the set of radiation hybrid markers and randomly produced raw sequences. The public consortium estimated the draft genome sequence covered 88–90% (together with other public databases up to 94%) of the genome and Celera estimated that their draft sequence contained 91–99% (2).

The inclusion of the set of NotI sequences can be used to assess the coverage of the draft sequences. Unmethylated NotI sites from the CBMI-Ral-STO cell line were anticipated to be present in the NotI clone grids, while the HTGS database contains both methylated and unmethylated NotI sites.

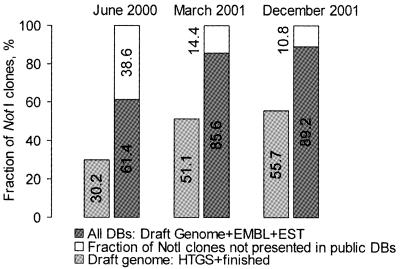

The draft human genome sequence (1,2) contains a significant portion of the NotI sequence collection (Fig. 2). With stringent criteria, 55.7% of the NotI flanking sequences were present in a recent public assembly of the human genome (December 2001, identity ≥90%). Inclusion of the Celera sequences identified an additional 1.5% of NotI flanks. All public databases (EMBL + HTGS + EST) matched 89.2% of the NotI flanking sequences and search stringency is important here: this number increased to 91.1% at identity ≥78% and went down to 84.1% at identity ≥95%. The public draft sequence contained 19 552 NotI sites (i.e. 39 104 NotI flanking sequences). The EMBL coverage is misleading, as the EMBL database contains more than 4500 NotI flanking sequences generated in the previous studies (6,16).

Figure 2.

Fraction of NotI flanking clones present in the EMBL, EST and HTGS databases (similarity ≥90% over 50 bp).

Comparison with the complete chromosome 21 and 22 sequences (3,4) revealed several interesting features. The assembled chromosome 21 sequence contains 122 NotI sites (methylated and unmethylated). Ichikawa et al. (13) cloned 40 NotI sites and it was sufficient to construct the complete NotI restriction map. This map contained 43 NotI fragments but, using incomplete digestion with 40 NotI clones, it was possible to order all NotI fragments. The NotI flanking sequence database contains 49 NotI sites for chromosome 21 (Table 2). Altogether, out of 390 possible NotI sites on chromosomes 21 and 22, the NotI database contains 168 (43%) sites. From our data we can conclude that unmethylated NotI sites represent at least 43%. Eighteen clones that were identified in our work (5%) were present in public sequences with one nucleotide mismatch in the NotI site. Thus these clones either represent polymorphic NotI sites or result from sequencing errors in the public data.

Table 2. Comparison of NotI flanking sequences with finished sequences of chromosomes 21 and 22.

|

NotI sitesa |

Chromosome |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | 22 | 21 + 22 | |

| Total | 122 | 268 | 390 |

| Sites with identityb to NotI flanking sequences | 42 | 108 | 150 |

| Sites (with one substitution) with identityb to NotI flanking sequences | 7 | 11 | 18 |

| Total sites with identityb to NotI flanking sequences | 49 | 119 | 168 |

aSites with surrounding 1 kb were considered.

bSimilarity 90%, length 50 bp, homology region includes NotI sites.

Considering the redundancies in the draft genomic sequences and large differences in methylation status of NotI sites across cell lines (15) it is difficult to estimate the coverage of NotI flanks in this study. Based on the completed chromosome 21 and 22 sequences we can draw some conclusions. First, it was shown that chromosome 22 contains >2-fold more genes than chromosome 21, and we see the same ratio within the NotI flanking sequences. We have demonstrated that nearly all of the NotI clones contained genes (6,9) and suggested that 12.5–20% of all genes contain NotI sites (9). This correlates well with the number of genes on chromosomes 21 and 22 (168/770 = 22%). Second, the two chromosomes contain 390 NotI sites. Therefore, if we assume that each NotI site is associated with a gene (in reality we have shown that sometimes two genes are located close to the same NotI site; 30), then almost half of the genes contain NotI sites. This estimate appears excessive. We suggest that there are two distinct classes of NotI sites. The first group is ‘live’ NotI sites that are unmethylated or, more accurately, are not always methylated. They are located in CpG islands and associated with genes. The ‘dead’ NotI sites comprise the second group and they are (always) methylated and located outside functional CpG islands and genes. Further research is necessary to test this hypothesis.

NotI sequences as a tool for gene identification

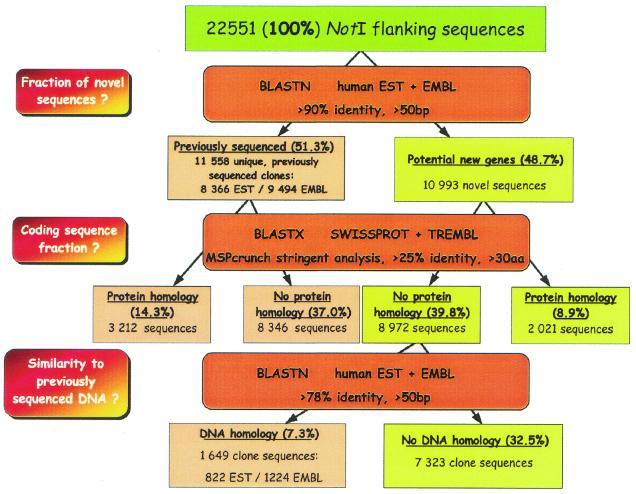

More stringent parameters were applied to the gene discovery pipeline than in the pilot study (Fig. 3; 16) (see Materials and Methods). A check against the SWISSPROT and TREMBL databases indicated that 23.2% of the total NotI flanking sequences were significantly similar to known proteins.

Figure 3.

NotI flanking sequences general analysis scheme.

Of the 22 551 unique NotI flanking sequences 48.7% were novel, as they were not previously present in the EMBL and EST databases. For these novel sequences, potential novel coding sequences were analyzed. Based on the stringent selection criteria 8.9% of the total sequences were identified with similarity to known proteins. Among the remaining 8972 novel clone sequences, 1649 (7.3%) sequences had identity of >78% to sequences in the EMBL and EST databases and 7323 (32.5%) clones were not similar to previously identified sequences.

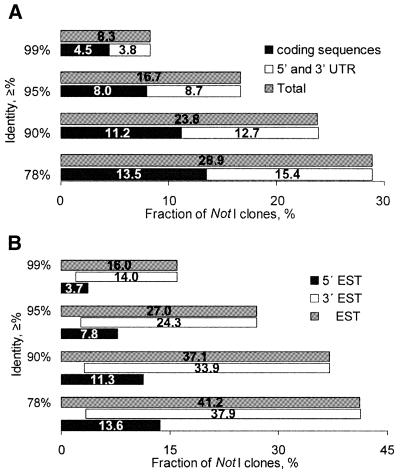

Results of a sequence comparison with full-length human cDNA protein coding sequences from Unigene are shown in Figure 4A. As compared to results obtained in the pilot experiment (16) the portion with significant matches increased ∼2-fold.

Figure 4.

Similarity between NotI and human Unigene mRNA sequences (A) and NotI and expressed sequences (B).

The number of sequences matching 5′ and 3′ ESTs is higher than the total number of NotI sequences that are likely to be expressed, e.g. 11.3% + 33.9% = 45.2% > 37.1% (for 90% similarity; see Fig. 4B). This is because the same NotI sequence can match 5′ as well as 3′ ESTs. These data further support a previous suggestion that many of the matching ‘3′ EST’ sequences are actually situated in the 5′ ends of genes that contain NotI sites in their first exons (6,16). Venter et al. (2) extended these results for the entire genome and demonstrated a strong correlation between CpG islands and first coding exons.

To estimate how many NotI flanking sequences matched genes from other organisms, NotI sequences were compared to ESTs from all organisms. Several hundred additional ESTs (e.g. 661 for identity ≥78%) were similar to NotI flanking sequences. These NotI clones most likely represented human genes evolutionarily related to the genes from other organisms.

It is well known that CpG islands are associated with genes and their most important feature is an absence of cytosine methylation (1,5). The human genome sequence data cannot discriminate between methylated and unmethylated cytosines. There are several algorithms for the identification of CpG islands on the basis of primary sequence. One quantitative definition holds that CpG islands are regions of DNA >200 bp long with a C+G content of >50% and a ratio of ‘observed versus expected’ frequency of CG dinucleotides which exceeds 0.6 (1,31,32). The ratio for the entire genome is approximately 0.2 (1). According to the previous data 82% of NotI sites are located in CpG islands (32,33). It is important to note that these data were obtained using either computational methods or limited experimental data sets. Using the NotI cloning method only unmethylated NotI sites can be isolated. An analysis of CG content for the first 350 bp is shown in Table 3. Comparing these data with Lander et al. (1), two main features are apparent: the fraction of sequences with >80% CG content is nine times higher in the NotI collection, i.e. 142 versus 22 sequences. Another striking finding is that even NotI flanking sequences with a CG content <50% have a very high ratio of observed versus expected frequency of CG dinucleotides (0.71). This suggests that essentially all NotI flanking sequences generated in the study are located in CpG islands and, therefore, the computational method misses at least 8.7% of CpG islands associated with NotI sites.

Table 3. GC content of NotI flanks.

| GC content (%) of NotI flanks | No. of NotI flanks | Percentage of NotI flanks | Ratio between observed and expected CG pairs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 22 551 | 100 | 0.77 |

| >80 | 142 | 0.6 | 0.96 |

| 70–80 | 4005 | 17.8 | 0.87 |

| 60–70 | 9629 | 42.7 | 0.78 |

| 50–60 | 6813 | 30.2 | 0.70 |

| 40–50 | 1751 | 7.8 | 0.70 |

| <40 | 211 | 0.9 | 0.75 |

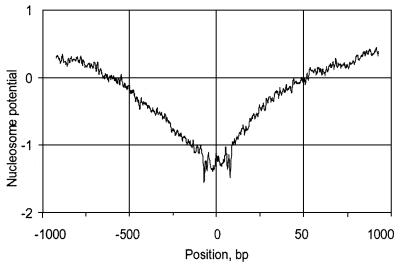

Regulatory regions, especially promoters, are negatively associated with the formation of nucleosomes (28). A total of 142 chromosome 3-specific NotI sequences for which 1 kb flanks were available in the human genome sequence (phase 3 ‘finished’ sequence) were selected for an analysis of nucleosome formation potential (NFP). Positive NFP values indicate sequences that are likely to form nucleosomes efficiently, while negative scores indicate sequences likely to have poor nucleosome stacking ability. The results demonstrate (Fig. 5) that regions flanking NotI sites are less likely to form nucleosomes efficiently as their NFP values are below –1 and therefore resemble promoter regions in this feature.

Figure 5.

The NFP of NotI flanking sequences calculated as in Levitsky et al. (28). NotI sites are located at position 0. Negative scores indicate sequences likely to have poor nucleosome stacking ability.

Conclusions

It should be emphasized that the enormous efforts deployed on sequencing the human genome (1,2) are extremely important, however, there remains a critical role for verified, integrated maps. In sequencing, the short and long repeats spread throughout the genome are sources of numerous errors. These errors are difficult to identify with a shotgun strategy, but they become evident when mapping information is combined with the sequence. Furthermore, difficulties in sequence assembly caused by the existence of large families of recently duplicated genes and pseudogenes are easier to resolve using integrated maps.

In many cases, sequence and mapping information is duplicated, overlapping or contradictory. One must always keep in mind that even absolutely correct and long nucleotide sequences may be localized incorrectly along the chromosomal DNA if the appropriate accompanying mapping information is ignored. For this reason, in spite of the vast amount of information presently available, there is an urgent need to reconcile this information in a unified framework, to generate an integrated non-controversial map for each individual chromosome.

We believe that the NotI flanking sequences generated in this study will be helpful in verifying contig assemblies and in connecting orphan sequence contigs into a final genome assembly. NotI clones can serve as STSs that can be mapped precisely using PFGE and FISH. These flanking sequences have already been helpful in the isolation and mapping of new genes and resolving ambiguities in chromosome 3 maps (6,17–22,34). We think that the NotI clones will also be helpful as probes to close existing gaps in the draft human genome sequence and in estimating the completeness of the human genome sequence due to the independent approach used in this study. The data demonstrate that the draft human genome sequence has a strong bias against NotI flanking sequences, as a significant number of the human NotI sequences were not detected.

Several explanations can be offered to account for the low representation of NotI flanking sequences in the draft human genome sequences. We have cloned all of the NotI sites and constructed a physical map for two chromosome 3 regions containing tumor suppressor genes (6,34,35; A.I.Protopopov, V.I.Kashuba, V.Zabarovska, O.Muravenko, M.I.Lerman, G.Klein and E.R.Zabarovsky, unpublished results). In the course of these studies it became apparent that large-insert vectors from these regions were unstable and sensitive to deletions and rearrangements and that the original map was erroneous (35–37; A.I.Protopopov, V.I.Kashuba, V.Zabarovska, O.Muravenko, M.I.Lerman, G.Klein and E.R.Zabarovsky, unpublished results; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/Entrez/maps.cgi?org=hum&chr=3). Thus one potential explanation is that the cloning of some NotI site-containing regions may be selected against in experiments with large-insert cloning vectors. Our experience has also proven that even in small-insert plasmid vectors some human sequences are more easy to clone than others. In our procedure, we directly selected for clones containing NotI sites, while in a shotgun sequencing approach such sequences could be under-represented. An alternative explanation, based on the observation that some NotI flanking sequences can have 100% identity over long DNA stretches (22), is that some NotI sites were incorrectly fused in the assembly process. Furthermore, our experience demonstrates that sometimes it is very difficult to read NotI flanking sequences because of the extremely high CG content. During human genome assembly such sequences would be eliminated as possessing low quality data. Further experimental analysis is needed to conclusively identify the cause(s) of the bias.

The results of this work show that NotI flanking sequences are a rich source for identification of new genes. A difference in this study compared with the pilot experiment is the lower fraction of NotI sequences with protein similarity (23.2% now versus 51% in the pilot study), resulting from more stringent analysis criteria. The comparatively high level of sequence errors (1.5% for the first 160 bp) is likely to be a consequence of the CG-rich stretches of DNA. In some cases CG content exceeded 95% over 100 bp. However, the sequencing accuracy does not affect the main results of the study, as short matches were used for searches. Moreover, lower stringency criteria for searches (25% for proteins and 75–78% for DNA) did not significantly alter the results.

It is difficult to precisely determine the number of NotI sites in the human genome and the unmethylated portion in any particular cell type. Our rough estimation (based on chromosomes 21 and 22) is that the human genome contains 15 000–20 000 NotI sites, of which 6000–9000 are unmethylated in a subset of cells.

The detection of CpG islands is difficult using only sequence data, as evidenced by existing computational methods missing a significant fraction of functional CpG islands. We conclude that unmethylated DNA stretches with a high frequency of CpG dinucleotides can be found in regions with low CG content. This conclusion is consistent with the surprising deduction made by Venter et al. (2): significantly more genes than expected are located in DNA regions with low CG content. This suggests that computational identification of CpG islands will improve if more weight is placed on the ratio of observed versus expected frequency of CG dinucleotides, rather than overall CG content.

In summary, this work has demonstrated that sequences flanking NotI restriction sites can be used to complement large-scale human genome sequencing. As the organization of the human genome and that of other mammals is similar, this approach will contribute to the success of future sequencing projects.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by research funds from Pharmacia Corp. to the Center for Genomics and Bioinformatics, as well as grants from the Swedish Cancer Society, The Swedish Research Council, the Ingabritt och Arne Lundbergs Foundation, The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Karolinska Institute, The Swedish Foundation for International Cooperation in Research and Higher Education (to A.S.K.) and partly by the Russian National Human Genome Program (grants to O.V.M. and L.L.K.).

DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession nos+ To whom correspondence should be addressed at: Microbiology and Tumor Biology Center, Karolinska Institute, Box 280, 171 77 Stockholm, Sweden. Tel: +46 8 728 6750; Fax: +46 8 319 470; Email: The authors wish it to be known that, in their opinion, the first two authors should be regarded as joint First Authors AQ936570–AQ939834, AJ322533–AJ343893

REFERENCES

- 1.Lander E.S., Linton,L.M., Birren,B., Nusbaum,C., Zody,M.C., Baldwin,J., Devon,K., Dewar,K., Doyle,M., FitzHugh,W. et al. (2001) Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature, 409, 860–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Venter G.J., Adams,M.D., Myers,E.W., Li,P.W., Mural,R.J., Sutton,G.G., Smith,H.O., Yandell,M., Evans,C.A., Holt,R.A. et al. (2001) The sequence of the human genome. Science, 291, 1304–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunham I., Hunt,A.R., Collins,J.E., Bruskiewich,R., Beare,D.M., Clamp,M., Smink,L.J., Ainscough,R., Almeida,J.P., Babbage,A. et al. (1999) The DNA sequence of human chromosome 22. Nature, 402, 489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hattory M., Fujiyama,A., Taylor,T.D., Watanabe,H., Yada,T., Park,H.-S., Toyoda,A., Ishii,K., Totoki,Y., Choi,D.-K. et al. (2000) The DNA sequence of human chromosome 21. Nature, 405, 311–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bird A.P., (1987) CpG islands as gene markers in the vertebrate nucleus. Trends Genet., 3, 342–347. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kashuba V.I., Gizatullin,R.Z., Protopopov,A.I., Li,J., Vorobieva,N.V., Fedorova,L., Zabarovska,V.I., Muravenko,O.V., Kost-Alimova,M., Domninsky,D.A. et al. (1999) Analysis of NotI linking clones isolated from human chromosome 3 specific libraries. Gene, 239, 259–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zabarovsky E.R., Boldog,F., Erlandsson,R., Allikmets,R.L., Kashuba,V.I., Marcsek,Z., Stanbridge,E., Sumegi,J., Klein,G. and Winberg,G. (1991) New strategy for mapping the human genome based on a novel procedure for construction of jumping libraries. Genomics, 11, 1030–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zabarovsky E.R., Kashuba,V.I., Zakharyev,V.M., Petrov,N., Pettersson,B., Lebedeva,T., Gizatullin,R., Pokrovskaya,E.S., Bannikov,V.M., Zabarovska,V.I. et al. (1994) Shot-gun sequencing strategy for long-range genome mapping: a pilot study. Genomics, 21, 495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allikmets R.L., Kashuba,V.I., Pettersson,B., Gizatullin,R., Lebedeva,T., Kholodnyuk,I.D., Bannikov,V.M., Petrov,N., Zakharyev,V.M., Winberg,G. et al. (1994) NotI linking clones as a tool for joining physical and genetic maps of the human genome. Genomics, 19, 303–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zabarovsky E.R., Boldog,F., Thompson,T., Scanlon,D., Winberg,G., Marcsek,Z., Erlandsson,R., Stanbridge,E.J., Klein,G. and Sumegi,J. (1990) Construction of a human chromosome 3 specific NotI linking library using a novel cloning procedure. Nucleic Acids Res., 11, 6319–6324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saito A., Abad,J.P., Wang,D.N., Ohki,M., Cantor,C.R. and Smith,C.L. (1991) Construction and characterization of a NotI linking library of human chromosome 21. Genomics, 10, 618–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arenstorf H.P., Kandpal,R.P., Baskaran,N., Parimoo,S., Tanaka,Y., Kitajima,S., Yasukochi,Y. and Weissman,S.M. (1991) Construction and characterization of a NotI-BsuE linking library from the human X chromosome. Genomics, 11, 115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ichikawa H., Hosoda,F., Arai,Y., Shimizu,K., Ohira,M. and Ohki,M. (1993) A NotI restriction map of the entire long arm of human chromosome 21. Nature Genet., 4, 361–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gemmill R.M., Chumakov,I., Scott,P., Waggoner,B., Rigault,P., Cypser,J., Chen,Q., Weissenbach,J., Gardiner,K., Wang,H. et al. (1995) A second-generation YAC contig map of human chromosome 3. Nature, 28, 299–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hosoda F., Arai,Y., Kitamura,E., Inazawa,J., Fukushima,M., Tokino,T., Nakamura,Y., Jones,C., Kakazu,N., Abe,T. et al. (1997) A complete NotI restriction map covering the entire long arm of human chromosome 11. Genes Cells, 2, 345–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zabarovsky E.R., Gizatullin,R., Podowski,R.M., Zabarovska,V.V., Xie,L., Muravenko,O.V., Kozyrev,S., Petrenko,L., Skobeleva,N., Li,J., Protopopov,A. et al. (2000) NotI clones in the analysis of the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 1635–1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kashuba V., Protopopov,A., Podowski,R., Gizatullin,R., Li,J., Klein,G., Wahlestedt,C. and Zabarovsky,E. (2000) Isolation and chromosomal localization of a new human retinoblastoma binding protein 2 homologue 1a (RBBP2H1A). Eur. J. Hum. Genet., 8, 407–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Protopopov A., Kashuba,V., Podowski,R., Gizatullin,R., Sonnhammer,E., Wahlestedt,C. and Zabarovsky,E.R. (2000) Assignment of the GPR14 gene coding for the G-protein-coupled receptor 14 to human chromosome 17q25.3 by fluorescent in situ hybridization. Cytogenet. Cell Genet., 88, 312–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muravenko O.V., Gizatullin,R.Z., Protopopov,A.I., Kashuba,V.I., Zabarovsky,E.R. and Zelenin,A.V. (2000) Assignment of CDK5R2 coding for the cyclin-dependent kinase 5, regulatory subunit 2 (NCK5AI protein) to human chromosome band 2q35 by fluorescent in situ hybridization. Cytogenet. Cell Genet., 89, 160–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muravenko O.V., Gizatullin,R.Z., Al-Amin,A.N., Protopopov,A.I., Kashuba,V.I., Zabarovsky,E.R. and Zelenin,A.V. (2000) Human SSI3 gene. Map position 17q25.3. Chromosome Res., 8, 561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gizatullin R.Z., Muravenko,O.V., Al-Amin,A.N., Wang,F., Protopopov,A.I., Kashuba,V.I., Zelenin,A.V. and Zabarovsky,E.R. (2000) Human NRG3 gene maps to position 10q22-q23. Chromosome Res., 8, 560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kashuba V.I., Protopopov,A.I., Kvasha,S.M., Gizatullin,R.Z., Wahlestedt,C., Kisselev,L.L., Klein,G. and Zabarovsky,E.R. (2002) hUNC93B1: a novel human gene representing a new gene family and encoding an unc-93-like protein. Gene, 283, 209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sambrook J., Fritsch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd Edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 24.Ernberg I., Falk,K., Minarovits,J., Busson,P., Tursz,T., Masucci,M.G. and Klein,G. (1989) The role of methylation in the phenotype-dependent modulation of Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 2 and latent membrane protein genes in cells latently infected with Epstein-Barr virus. J. Gen. Virol., 11, 2989–3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altschul S.F., Gish,W., Miller,W., Myers,E.W. and Lipman,D.J. (1990) Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol., 215, 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gish W., and States,D.J. (1993) Identification of protein coding regions by database similarity search. Nature Genet., 3, 266–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sonnhammer E.L.L., and Durbin,R. (1997) Analysis of protein domain families in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genomics, 46, 200–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levitsky V.G., Podkolodnaya,O.A., Kolchanov,N.A. and Podkolodny,N.L. (2001) Nucleosome formation potential of eukaryotic DNA: calculation and promoters analysis. Bioinformatics, 17, 998–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stanhope M.J., Lupas,A., Italia,M.J., Koretke,K.K., Volker,C. and Brown,J.R. (2001) Phylogenetic analyses do not support horizontal gene transfers from bacteria to vertebrates. Nature, 411, 940–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y., Corcoran,M., Rasool,O., Ivanova,G., Ibbotson,R., Grander,D., Iyengar,A., Baranova,A., Kashuba,V., Merup,M. et al. (1997) Cloning of two candidate tumor suppressor genes within a 10 kb region on chromosome 13q14, frequently deleted in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Oncogene, 15, 2463–2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gardiner-Garden M., and Frommer,M. (1987) CpG islands in vertebrate genomes. J. Mol. Biol., 196, 261–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larsen F., Gundersen,G., Lopez,R. and Prydz,H. (1992) CpG islands as gene markers in the human genome. Genomics, 13, 1095–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larsen F., Gundersen,G. and Prydz,H. (1992) Choice of enzymes for mapping based on CpG islands in the human genome. Genet. Anal. Tech. Appl., 9, 80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kashuba V.I., Szeles,A., Allikmets,R., Nilsson,A.S., Bergerheim,U.S., Modi,W., Grafodatsky,A., Dean,M., Stanbridge,E.J., Winberg,G. et al. (1995) A group of NotI jumping and linking clones cover 2.5 Mb in the 3p21-p22 region suspected to contain a tumor suppressor gene. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet., 2, 144–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei M.H., Latif,F., Bader,S., Kashuba,V., Chen,J.Y., Duh,F.M., Sekido,Y., Lee,C.C., Geil,L., Kuzmin,I. et al. (1996) Construction of a 600-kilobase cosmid clone contig and generation of a transcriptional map surrounding the lung cancer tumor suppressor gene (TSG) locus on human chromosome 3p21.3: progress toward the isolation of a lung cancer TSG. Cancer Res., 7, 1487–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kok K., van den Berg,A., Veldhuis,P.M., van der Veen,A.Y., Franke,M., Schoenmakers,E.F., Hulsbeek,M.M., van der Hout,A.H., de Leij,L., van de Ven,W. et al. (1994) A homozygous deletion in a small cell lung cancer cell line involving a 3p21 region with a marked instability in yeast artificial chromosomes. Cancer Res., 15, 4183–4187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murata Y., Tamari,M., Takahashi,T., Horio,Y., Hibi,K., Yokoyama,S., Inazawa,J., Yamakawa,K., Ogawa,A., Takahashi,T. et al. (1994) Characterization of an 800 kb region at 3p22-p21.3 that was homozygously deleted in a lung cancer cell line. Hum. Mol. Genet., 8, 1341–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]