Abstract

Objective:

To carry out a systematic appraisal of the current status of the use of metallic endobiliary stents in the treatment of benign biliary strictures.

Methods:

A computerized search of the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases identified 37 studies providing detailed clinical course data on outcome of metallic endobiliary stent placement in 400 patients. Pooled data were examined for etiology of stricture, indications for stent placement, procedure-related complications, and outcome with reference to stent patency.

Results:

The median (range) number of patients per report was 8 (2–54) with a median recruitment period of 44 (9–126) months. The most frequent indications were postoperative biliary strictures in 123 (31%), stenosed biliary-enteric anastomoses in 79 (20%), and biliary strictures following liver transplantation in 88 (22%). During a median follow up of 31 (1–111) months, 139 (35%) stents occluded, and there are little patency data beyond 2 years after deployment, with 99 (25%) known to be patent at 3 years from stent placement.

Conclusions:

These pooled data on 400 patients constitute the largest collective report to date on the use of metallic endobiliary stents for benign biliary strictures. The results show a critical lack of data on long-term patency such that at the present time, metallic endobiliary stents should not be used for benign stricture in those patients with a predicted life expectancy greater than 2 years.

This systematic appraisal on the deployment of metallic endobiliary stents for benign biliary stricture analyses pooled data on a cohort of 400 patients. Although procedure-related complication rates were low, there are limited long-term patency data with 99 (25%) known to be patent at 3 years from stent placement.

Metallic endobiliary stents are well established for the treatment of malignant obstructive jaundice.1–3 When used for palliation of jaundice from unresectable malignancy, the relatively short patient-survival time after diagnosis often means that death intervenes before stent-related complications such as occlusion occur.1 Further, when problems of stent occlusion do intervene, they can be managed by short-term salvage strategies such as stent-within-stent therapy and/or percutaneous drainage.4,5

The increased availability of equipment and expertise has led to a broadening of the described settings for the use of metal stents, and many reports now describe their use for treatment of benign biliary strictures.6–9 However, although the technical process of stent deployment may differ relatively little between benign and malignant strictures, the biomechanics of the stent-bile duct interface are likely to vary considerably between malignant and benign strictures. Further, from a practical clinical perspective, the potential consequences of a metal stent placed across a benign biliary stricture are influenced by the patient's greater expected survival time10–12 and the requirement for longer-term treatment strategies when stent occlusion occurs.

The current evidence-base for the use of metallic endobiliary stents in benign biliary strictures derives almost entirely from small, single-institutional cohort series, which continue to accrue.5,13–17 The aim of this study is to carry out a systematic appraisal of the available evidence with the intention that analysis of pooled data can provide critical insight into the role of metal endobiliary stents in benign biliary strictures. In the absence of an evidence-base from randomized trials, a pooled systematic analysis underpins the current evidence-base and can provide a definitive information source.

METHODS

Literature Search Strategy

A computerized search was made of the MEDLINE database for the period from January 1966 to November 2003 inclusive and of the EMBASE database for the period from January 1980 to November 2003. The OVID search engine (Version 9; Ovid Technologies, New York, NY) was used. In MEDLINE, the MESH headings “cholestasis” and “bile duct obstruction, extrahepatic” yielded 15,439 hits. The keyword “bile duct stricture” yielded 173 and the keyword “biliary stricture” 321. Combination of these biliary stricture searches to exclude duplicates yielded 15,741 hits in MEDLINE and 9017 in EMBASE. Next, the MESH heading “stents” was combined with the keyword “metal stents” to yield 18,197 hits in MEDLINE and 12,084 hits in EMBASE. Finally, the biliary stricture search results were combined (meshed) with the metal stent search results to produce 837 MEDLINE hits and 658 EMBASE hits, respectively. Of the articles identified by the EMBASE search, 650 were also detected in the MEDLINE search. These 845 (837 MEDLINE plus 8 unduplicated EMBASE) abstracts were then downloaded and studied.

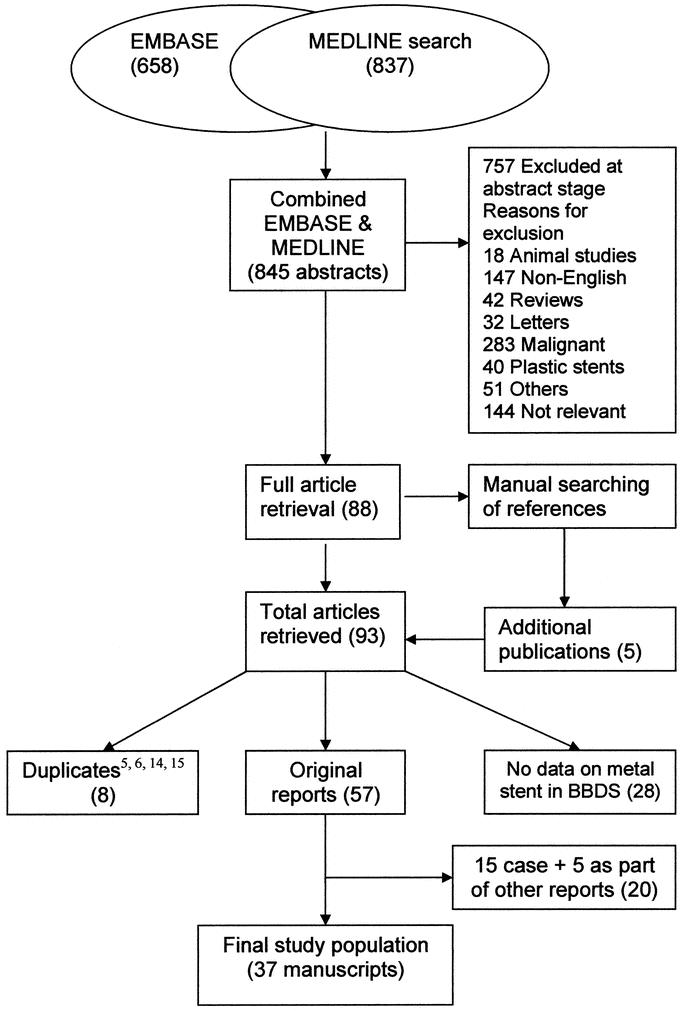

Papers were excluded if they were reviews, letters without original data, non-English, animal studies, reports on patients with strictures due to malignant disease, and studies with plastic stents. If there was any doubt as to the suitability of the article after reading the abstract, the full manuscript was obtained. A total of 757 articles were rejected on the basis of the examination of the downloaded abstract with the rejection criteria outlined in Figure 1. This process of exclusion yielded 88 full articles. Manual searching of the reference lists of these articles identified 5 additional studies (including 2 published abstracts of studies presented at scientific meetings) missed by electronic searching giving a total of 93 studies (Fig. 1). After study of these full manuscripts, further exclusions were necessary as follows: 28 papers without any data pertaining to the use of metal stents in benign disease, 15 case reports; 5 further papers describing a single case each of metallic endobiliary stent deployment for benign disease in studies predominantly reporting outcome in patients with malignant strictures, and 8 sequential publications5,6,18–21 with overlapping patient populations (in these cases only the original report was retained). These exclusions produced a final study population of 37 manuscripts.

FIGURE 1. Flow chart of search history. BBDS indicates benign bile duct stricture.

Data Extraction

Each of the 37 articles was reviewed independently by 2 authors who separately extracted data on the following categories for presentation: number of patients undergoing metal stent placement for benign biliary stricture, recruitment period, etiology of biliary stricture, indication for stenting, number of stents occluded, delay to stent occlusion and annual patency, and management of occluded stents. Extracted data were then crosschecked between authors to rule out discrepancy.

Study Population

The 37 manuscripts yielded information on 908 patients in whom metallic endobiliary stents were placed, with 400 of these undergoing metal stent placement for benign biliary stricture. These 400 patients constitute the principal study population. The use of the term “benign biliary stricture” was applied to all 400 in their original reports.

The median (range) number of patients per report was 8 (2–54). The median (range) recruitment period in the 21 studies providing data on enrollment was 44 months (9–126 months) (these studies encompass 271 [68%] patients). The median age (range) in 24 studies providing data on patient age was 54 years (3 months to 92 years).

Principal Outcomes

For the purposes of this study, the index episode of insertion of a metallic endobiliary stent was regarded as the point of commencement for clinical course and stent patency data regardless of prior management of biliary stricture. Similarly, occlusion of this index metal stent was regarded as the end point for assessment of primary stent patency. Pooled data were examined for information in the following outcome categories:

Etiology and duration of stricture prior to stent placement

Indications for metal stent insertion

Route of stent insertion

Profile of complications

Stent patency

Management of stent occlusion

For the purposes of this study, primary patency was defined as the initial period of patency of the index metal stent. This period was taken to commence at placement and end with any episode of occlusion. Any subsequent period of stent patency obtained by therapeutic intervention was excluded for the purposes of this analysis.

Statistical Analyses

Data are presented as median (range) unless otherwise stated. Interpretative analyses based on pooled as opposed to individual patient data cannot detect censored, missing, and incomplete follow-up; hence, survival analyses cannot be conducted on these data.

RESULTS

Etiology and Duration of Stricture Before Stent Placement

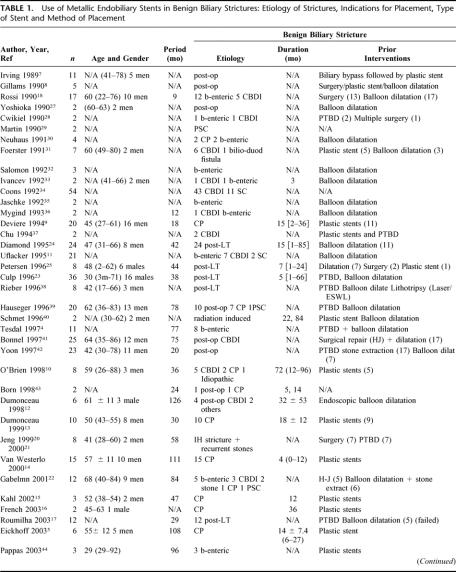

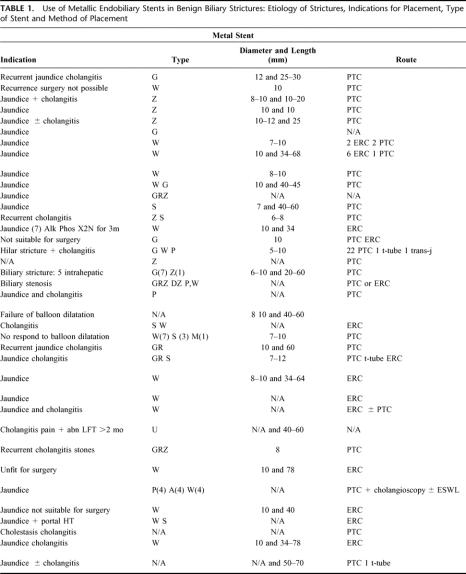

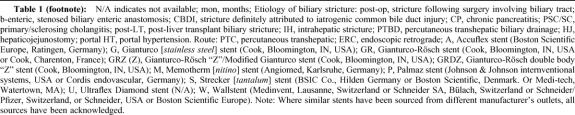

The etiology of benign biliary stricture (Table 1) was postsurgical injury to the common bile duct in 123 (31%). A further 79 (20%) patients had stents placed for postoperative strictures at biliary-enteric anastomoses. Eighty-eight patients (22%) had biliary strictures complicating liver transplantation. Nonsurgical causes included strictures secondary to chronic pancreatitis in 69 (17%), primary sclerosing cholangitis in 21 (5%), and strictures secondary to ductal (both intrahepatic and extrahepatic) stone disease in 8 (2%). Rare causes (in 12 patients) included postradiotherapy stricture, bilio-duodenal fistula, and idiopathic stricture.

TABLE 1. Use of Metallic Endobiliary Stents in Benign Biliary Strictures: Etiology of Strictures, Indications for Placement, Type of Stent and Method of Placement

TABLE 1. Use of Metallic Endobiliary Stents in Benign Biliary Strictures: Etiology of Strictures, Indications for Placement, Type of Stent and Method of Placement

TABLE 1. (footnote):

The median (range) duration of the stricture prior to the insertion of metallic stents in the 14 studies (144 [36%] patients) providing these data was 15 months (1 week to 96 months).

Indications for Metal Stent Insertion

In a majority of reports (where indication was stated), a metal stent was inserted following the failure of other methods of treatment of jaundice/cholangitis (Table 1). Prior surgical repair of biliary stricture had been attempted in 80 (20%). Prior placement of a plastic stent had been attempted in 79 (20%) and percutaneous and/or endoscopic balloon dilatation employed in a total of 206 (52%). Information on interventions prior to placement of metal stent was not available for the remaining 35 patients.

Route of Stent Insertion

Metal stents were inserted via the percutaneous transhepatic route in 199 (50%), via endoscopic retrograde access (ERC) in 69 (17%), and via a combination of PTC and ERC in 42 (11%) (Table 1). In the 25 studies (233 [58%] patients) providing information relating to diameter/length of metal stent, the median stent diameter was 10 mm (5–12 mm) and stent length was 34 mm (10–78 mm).

Profile of Complications

Stent migration or dislodgement was reported in 15 (4%) patients. Other complications reported were hepatic abscess or sepsis (5), bile leak (2), hemobilia (3), and stone formation above the stent (2).

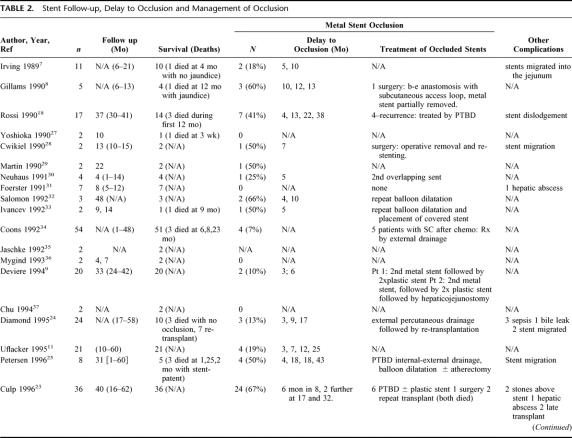

Stent Patency

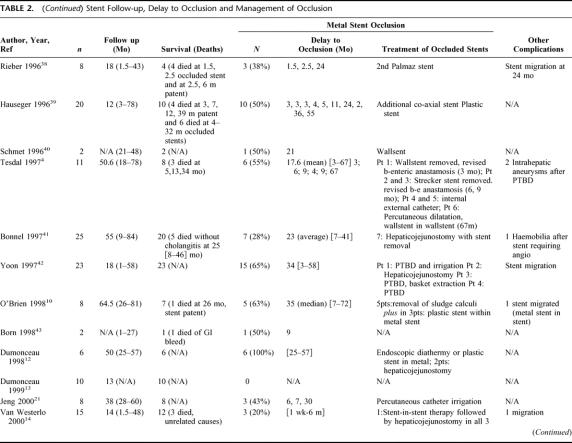

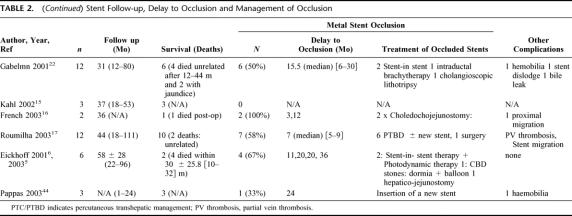

The median follow-up period after insertion of metal stents was 31 months (range, 1–111 months) in the 34 manuscripts (391 [98%] patients) providing these data (Table 2). During follow-up, 139 (35%) patients experienced stent occlusion. The median delay to the first episode of stent occlusion was 9 months (range, 1 week to 67 months). There was no evidence that the etiology of the underlying stricture had any effect on outcome: patency rates at 2 years after stent insertion were 41% for strictures complicating chronic pancreatitis, 44% for postliver transplant strictures, and 38% for strictures complicating cholecystectomy.

TABLE 2. Stent Follow-up, Delay to Occlusion and Management of Occlusion

TABLE 2. (Continued) Stent Follow-up, Delay to Occlusion and Management of Occlusion

TABLE 2. (Continued) Stent Follow-up, Delay to Occlusion and Management of Occlusion

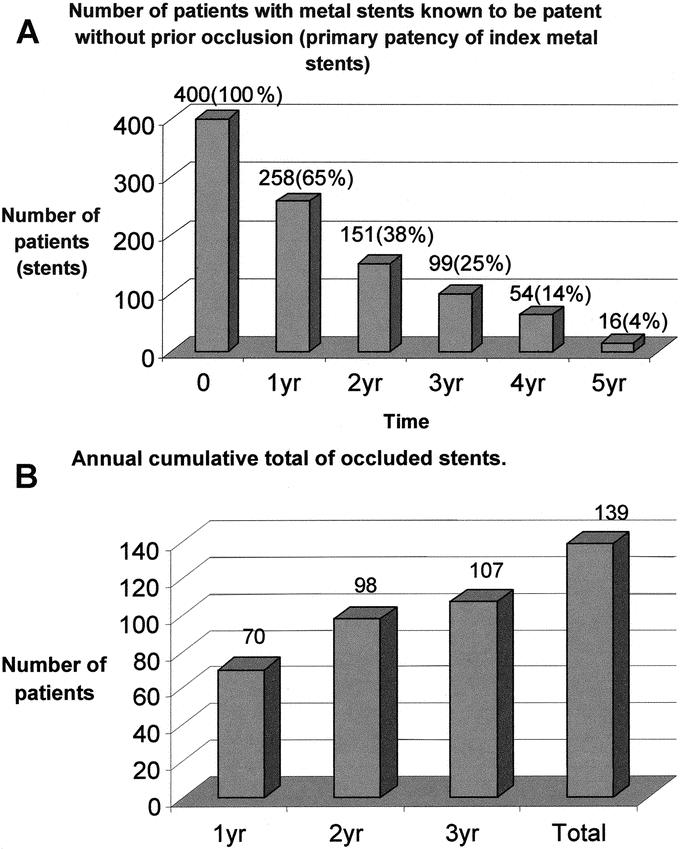

Variation in follow-up periods between studies means that overall annual patency data cannot be derived from pooled data. Pragmatic information is provided on the number of patients with metal stents known not to have occluded (primary patency) on an annual basis after stent deployment (Fig. 2A) and also on the number of stents known to have occluded annually after deployment (Fig. 2B). During this period of primary patency, the number of patients with patent stents and the number of patent stents are equivalent terms.

FIGURE 2. A, Number of stents known to be patent annually after deployment. The data in columns 1 through 6 refer to the number of patients with stents known to be patent without prior occlusion of this index metal stent at annual intervals. B, Annual cumulative total of occluded stents. The columns refer to annual totals of occluded stents. The difference between the number of stents known to have occluded at 3 years and the number known to be patent arises as the time to occlusion is not available for all patients.

Management of Stent Occlusion

The management of occluded metal stents was achieved by a variety of nonsurgical methods such as placement of a new stent (either plastic or a second metal stent) within the lumen of the occluded stent in 34 (24%), percutaneous biliary drainage or irrigation with or without repeat balloon dilatation in 54 (39%), and removal of sludge or calculi with endobiliary basket or balloon/cholangioscopic lithotripsy in 7 (5%). Operative removal of occluded stents was reported in 12 (9%) cases (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Analyses of pooled data are critically influenced by the nature of their constituent reports and by their inclusion and exclusion criteria. More subtle influences can be induced by positive publication bias and variations in available technology and clinical skills and the composition of patient cohorts. In the present study, a further specific issue is that differentiation between benign and malignant strictures can be complex, the 2 conditions can coexist, and the diagnostic rigor applied in distinguishing benign from malignant disease is likely to vary between studies. Bearing these limitations in mind, the present study provides a detailed and readily traced search history, factors for inclusion and exclusion are clearly identified, and the resulting group of 400 represents the largest pooled cohort of patients with benign biliary stricture treated by metal endobiliary stents.

The overview establishes that the median number of patients per report is low and further that the largest single-institutional cohort does not exceed 54. Recruitment periods are lengthy, and it is worth emphasizing that these patients are not elderly as their median age was 54 years.

A key point established by this overview is the lack of consistency in terminology. First, there was considerable variation in the definition of a symptomatic bile duct stricture. Second is the lack of uniformity in the description of stent patency. The term “primary patency” refers to the initial period of stent patency and is thus relatively straightforward. However, an episode of cholangitis occurring during the period of primary stent patency was regarded by some as an adverse event rather than an indicator of stent occlusion.22 Further, recanalization of an occluded stent is referred to by a variety of terms, including secondary patency23 and primary-assisted patency.24,25 The present report highlights the lack of standardization in nomenclature and emphasizes the need for the adoption of agreed descriptors

The principal etiology was postoperative stricture of the common bile duct. In the majority, metal stents were not used as initial intervention: either endoscopic/percutaneous balloon dilatation or plastic stent placement being the preferred initial intervention. A distinct etiologic group are those patients (n = 88) with biliary stricture complicating liver transplantation. Several reports17,23–25 justified the use of metal stents in this subgroup on the basis that patients with biliary stricture complicating the clinical picture of chronic graft rejection would be likely to require retransplantation at some point in their illness. The metal stent therefore served as a bridge for treatment of the biliary stricture with the prospect that if the stent were to occlude, retransplantation including removal of the extrahepatic biliary tree and stent would be a technical option. The third and most heterogeneous subset comprised patients with biliary strictures not due to prior surgery or complicating chronic inflammatory states such as chronic pancreatitis. Key issues here are that strictures secondary to diseases, such as sclerosing cholangitis, may be multifocal and involve both the intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary tree. The practical issues raised are that jaundice may not be related to a dominant stricture and further that access to an occluded metal stent may be complicated by associated strictures. Distal bile duct strictures secondary to chronic pancreatitis were treated by metal stents in 69 patients. Biliary strictures complicating chronic pancreatitis are reported to be more predominant in patients with late-stage disease “end-stage” chronic pancreatitis26 and so may present in patients with considerable comorbidity in the form of diabetes, pancreatic exocrine insufficiency, and portal hypertension. These patients will be a high-risk surgical category and further are likely to have a limited life expectancy.

An important finding is the limited number of stents that are known to be patent more than 3 years after placement (Fig. 2A). At 2 years after placement, 151 (38%) were known to be patent, with this value falling to 99 (25%) at 3 years. As these data are pooled from reports with varying follow-up periods (and a median follow-up period of 31 months), actuarial stent patency rates may be better than depicted in Figure 2A. Indirect evidence suggesting better patency rates comes from the data that only 139 (35%) stents occluded within the 31-month follow-up period (Fig. 2B). It is evident that longer-term follow-up studies are required. Nonetheless, a conclusion based on the follow-up data highlighted in this systematic overview is that the evidence base pertaining to metal stent patency in benign biliary stricture more than 2 years out from initial deployment is extremely limited.

CONCLUSION

This study has carried out a systematic appraisal of the role of metallic endobiliary stents for the treatment of benign extrahepatic biliary stricture. The pooled data on 400 patients constitutes the largest collective report on this technique in this setting to date. The results show that, although stents can be deployed endoscopically or radiologically with relative ease and are associated with a low procedure-related complication rate, there is a critical lack of data on long-term patency. These limitations are brought into focus by these pooled data and lead to the conclusion that at the present time metallic endobiliary stents should not be used for benign stricture in those patients with a predicted life expectancy greater than 2 years.

Footnotes

Posters based on this study have been accepted for presentation at Digestive Disease Week, American Gastroenterology Association, New Orleans, LA May 2004 and at the 6th World Congress of the American Hepatopancreatobiliary Association, Washington DC, June 2004.

Reprints: Ajith K. Siriwardena, MD, FRCS, HPB Unit, Department of Surgery, Manchester Royal Infirmary, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9WL UK. E-mail: ajith.siriwardena@cmmc.nhs.uk.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fletcher DR. Clinical management of carcinoma of the exocrine pancreas: Endoscopic management. In: Howard JM, Idezuki Y, eds. Surgical Diseases of the Pancreas. London: Williams & Wilkins, 1998:515–522. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis PA, Williamson RCN. Pancreatic neoplasia: palliative treatment. In: Garden OJ, eds. A Companion to Specialist Surgical Practice: Hepato-Biliary and Pancreatic Surgery, 2nd ed. London: Saunders, 2001:411–425. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knyrim K, Wagner HJ, Pausch J, et al. A prospective randomised controlled trial of metal stents for malignant obstruction of the common bile duct. Endoscopy. 1993;25:207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tesdal IK, Adamus R, Poeckler C, et al. Therapy for biliary stenoses and occlusions with use of three different metalic stents: single centre experience. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1997;8:869–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eickhoff A, Jakobs R, Leonhardt A, et al. Self-expandable metal mesh stents for common bile duct stenosis in chronic pancreatitis: retrospective evaluation of long-term follow-up and clinical outcome pilot study. Z Gastroenterol. 2003;41:649–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eickhoff A, Jakobs R, Leonhardt A, et al. Endoscopic stenting for common bile duct stenoses in chronic pancreatitis: results and impact on long-term outcome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:1161–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Irving JD, Adam A, Dick R, et al. Gianturco expandable metallic biliary stents: results of a European clinical trial. Radiology. 1989;172:321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillams A, Dick R, Dooley JS, et al. Self-expandable stainless steel braided endoprosthesis for biliary strictures. Radiology. 1990;174:137–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deviere J, Cremer M, Baize M, et al. Management of common bile duct stricture caused by chronic pancreatitis with metal mesh self expandable stents. Gut. 1994;35:122–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Brien SM, Hatfield AR, Craig PI, et al. A 5-year follow-up of self-expanding metal stents in the endoscopic management of patients with benign bile duct strictures. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uflacker R, Vujic I, Chita MA. Benign biliary obstruction: long-term results of metallic Z stents as the definitive treatment. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1995;6:54. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dumonceau JM, Deviere J, Delhaye M, et al. Plastic and metal stents for postoperative benign bile duct strictures: the best and the worst. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:8–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dumonceau JM, Nicaise N, Deviere J. The ultraflex diamond stent for benign biliary obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc Clin North Am. 1999;9:541–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Westerloo DJ, Bruno MJ, Bergman JJ, et al. Self-expandable wall stents for distal common bile duct strictures in chronic pancreatitis: follow-up and clinical outcome of 15 patients. Gastroenterology. 2000;18(suppl 2):A4693. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kahl S, Zimmermann S, Glasbrenner B, et al. Treatment of benign biliary strictures in chronic pancreatitis by self-expandable metal stents. Dig Dis. 2002;20:199–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.French JJ, Charnley RM. Expandable metal stents in chronic pancreatitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2003;5:58–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roumilhac D, Poyet G, Sergent G, et al. Long-term results of percutaneous management for anastomotic biliary stricture after orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Transplantation. 2003;9:394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossi P, Bezzi M, Salvtori FM, et al. Recurrent benign biliary strictures: management with self-expanding metallic stents. Radiology. 1990;175:661–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maccioni F, Rossi M, Salvtori FM, et al. Metallic stents in benign biliary strictures: three-year follow-up. Cardiovasc Interv Radiol. 1992;15:360–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeng K, Sheen I, Yang F. Are expandable metallic stents better than conventional methods for treating difficult intrahepatic biliary strictures with recurrent hepatolithiasis? Arch Surg. 1999;134:267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeng K, Sheen I, Yang F. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopy in the treatment of complicated intrahepatic biliary strictures and hepatolithiasis with internal metallic stent. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2000;10:278–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gabelmann A, Hamid H, Brambs HJ, et al. Metallic stents in benign biliary strictures: long-term effectiveness and interventional management of stent occlusion. Am J Radiol. 2001;177:813–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Culp WC, McCowan TC, Lieberman RP, et al. Biliary strictures in liver transplant recipients: treatment with metal stents. Radiology. 1996;199:339–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diamond NG, Lee SP, Niblett RL, et al. Metallic stents for the treatment of intrahepatic biliary strictures after liver transplantation. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1995;6:755–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petersen BD, Maxfield SR, Ivancev K, et al. Biliary strictures in hepatic transplantation: treatment with self-expandable Z stents. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1996;7:221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siriwardana HPP, Siriwardena AK. End-stage chronic pancreatitis: a practical disease-descriptor. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2001;30:171–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshioka T, Sakaguchi H, Yoshimura H, et al. Expandable metallic biliary endoprosthesis: preliminary clinical evaluation. Radiology. 1990;177:253–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cwikiel W, Ivancev K, Lunderquist A. Metallic stents. Radiol Clin North Am. 1990;28:1203–1210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin EC, Laffey KJ, Bixon R, et al. Gianturco-Rosch biliary stents: preliminary experience. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1990;1:101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neuhaus H, Hagenmüller F, Griebel M, et al. Percutaneous cholangioscopic or transpapillary insertion of self-expanding biliary metal stents. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foerster EC, Hoepffner N, Domschke W. Bridging of benign choledochal stenoses by endoscopic retrograde implantation of metal stents. Endoscopy. 1991;23:133–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salomonowitz EK, Antonucci F, Heer M, et al. Biliary obstruction: treatment with self-expanding metal prosthesis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1992;3:365–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ivancev K, Petersen B, Hall L, et al. Percutaneous hepaticojejunostomy and choledocho-choledochal re-anastomosis using metallic stents [Technical note]. Cardiovasc Interv Radiol. 1992;15:256–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coons H. Metallic stents for the treatment of biliary obstruction: a report of 100 cases. Cardiovasc Interv Radiol. 1992;15:367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaschke W, Klose KJ, Strecker EP. A new balloon-expandable tantalum stent (Strecker-stent) for the biliary system: preliminary experience. Cardiovasc Interv Radiol. 1992;15:356–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mygind T, Hennild V. Expandable metallic endoprostheses for biliary obstruction. Acta Radiol. 1993;34:252–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chu KM, Lai ECS. Expandable metallic biliary stents. Aust N Z J Surg. 1994;64:836–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rieber A, Brambs H, Lauchart W. The radiological management of biliary complications following liver transplantation. Cardiovasc Interv Radiol. 1996;19:242–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hausegger K, Kugler C, Uggowitzer M, et al. Benign biliary stricture: is treatment with the Wallstent advisable? Radiology. 1996;200:437–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmets L, Delhaye M, Azar C, et al. Post radiotherapy benign biliary stricture: successful treatment by self-expandable metallic stent. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:149–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bonnel DH, Liguory CL, Lefebvre JF, et al. Placement of metallic stents for treatment of postoperative biliary strictures: long-term outcome in 25 patients. Am J Radiol. 1997;169:1517–1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoon HK, Sung KB, Song HY, et al. Benign biliary strictures associated with recurrent pyogenic cholangitis: treatment with expandable metallic stents. Am J Radiol. 1997;169:1523–1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Born P, Rosch T, Bruhl K, et al. Long-term results of endoscopic treatment of biliary duct obstruction due to pancreatic disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:833–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pappas P, Leonardou P, Kurkuni A, et al. Percutaneous insertion of metallic endoprosthesis in the biliary tree in 66 patients: relief of the obstruction. Abdom Imaging. 2003;28:678–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]