Abstract

Summary Background Data:

Although extensively studied in animal models, ischemic preconditioning has not yet been studied in clinical transplantation.

Objective:

To compare the results of cadaveric liver transplantation with and without ischemic liver preconditioning in the donor.

Patients and Methods:

Alternate patients were transplanted with liver grafts that had (n = 46, GroupPrecond) or had not (n = 45, GroupControl) been subjected to ischemic preconditioning. Liver ischemia-reperfusion injury, liver and kidney function, morbidity, and in-hospital mortality rates were compared in the 2 groups. Initial poor function was defined as a minimal prothrombin time within 10 days of transplantation <30% of normal and/or bilirubin >200 μmol/L.

Results:

The postoperative peaks of ASAT (IU/L) and ALAT (IU/L) were significantly lower in GroupPrecond (556 ± 968 and 461±495, respectively) than in the GroupControl (1073 ± 1112 and 997±1071, respectively). The rate of technical morbidity and the incidence of acute rejection were similar in both groups. Initial poor function was significantly more frequent in the GroupPrecond (10 of 46 cases) than in the GroupControl (3 of 45 cases). Hospital mortality rates were similar in the 2 groups. In multivariate analysis, body mass index of the donor, graft steatosis, and ischemic preconditioning were significantly predictive of the posttransplant peak of ASAT. In univariate analysis, only preconditioning was significantly associated with initial poor function.

Conclusions:

Compared with standard orthotopic liver transplant, ischemic preconditioning of the liver graft in the donor is associated with better tolerance to ischemia. However, this is at the price of decreased early function. Until further studies are available, the clinical value of preconditioning liver grafts remains uncertain.

Ischemic preconditioning of cadaveric livers significantly improves tolerance to ischemia following transplantation. However, it was also associated with significantly poorer initial graft function.

Ischemia-reperfusion injury is the main cause of liver graft failure.1–3 Several strategies4 have been designed to limit this injury and its consequences. These include discarding grafts with severe steatosis,5,6 optimizing the preservation solution,7 minimizing the ischemia time,8 and matching the quality of the graft to the status of the recipient.4 Several recent animal studies have shown that ischemic preconditioning, during which brief exposure to warm ischemia provides robust protection against injury during long periods of ischemia, increases tolerance to reperfusion injury. This phenomenon was first described for the heart9 and mainly for normothermic ischemia (or warm ischemia) injury in many experimental models.10,11 It has also been described for several tissues and organs including the liver.2,12–17

One preliminary study18 and 2 randomized studies19,20 in humans showed that, when livers were subjected to ischemic preconditioning (by transient portal triad clamping) before partial hepatectomy under continuous portal triad clamping, patients suffered from less postoperative liver injury as indicated by lower transaminase levels and endothelial cell injury. These 3 studies failed to demonstrate any advantage of preconditioning over the respective control groups in terms of postoperative liver function (similar prothrombine time and bilirubin levels), morbidity, or mortality rate. In addition, the protective effect of preconditioning on ischemia-reperfusion injury was lost for the patients that a priori need it most, namely, those >60 years and those with liver steatosis.19 Several experimental studies have reported that ischemic preconditioning has a beneficial effect on cold ischemia-reperfusion injury for different organs, including heart, intestine, lung, and kidney.21,22 The study by Arai et al in a rat model of liver transplantation23 showed that ischemic preconditioning increases survival. This is consistent with other studies24–27 with the exception of one.28 Few studies have tested this concept in humans, and those that have been done gave discordant data. Totsuka et al29 showed that livers from human donors who sustained cardiopulmonary arrest and were resuscitated had similar survival and function to those from other donors. In addition, the serum concentration of transaminases after transplantation appears to be lower in patients who receive organs from donors with prior cardiopulmonary arrest compared with those without. Conversely, Wilson et al30 showed that reversible cardiac arrest prior to graft harvesting did not trigger any preconditioning benefit in liver transplantation. Our aim was to evaluate the effects of ischemic preconditioning of the liver graft in the cadaveric donor on ischemia-reperfusion injury in the recipient. Alternate patients were transplanted with grafts that had or had not been preconditioned in the donor. Preservation injury, early graft function, mortality, morbidity, and patient survival after transplantation were compared in the 2 groups.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Population and Experimental Design

The study was conducted from January 2000 to January 2003. The study population included 91 consecutive patients who underwent a liver transplant: 1) in an elective situation, 2) with a whole cadaveric liver, 3) from a donor without cardiac arrest or severe hemodynamical instability prior to harvesting. Alternate patients were assigned to each of the study groups. Forty-six patients received a graft that had been preconditioned in the donor (10 minutes of portal triad clamping followed by 10 minutes of reperfusion followed by multiorgan harvesting, GroupPrecond) and 45 received a graft that had not been preconditioned (GroupControl). This protocol of preconditioning was the same than the one used in the 3 clinical studies reported so far.18,19 During the study period, 292 transplantations not fulfilling all the abovementioned conditions were not included in the study. The protocol was approved by the investigation and review board of our center and was always accepted by the teams harvesting other organs.

Surgical Procedures

Liver Harvesting

The rapid procurement technique of Starzl et al was used in both groups.8,31 The graft was perfused with cold University of Wisconsin solution.8 A wedge biopsy was performed at the beginning of the harvesting procedure to evaluate steatosis (baseline biopsy). This biopsy was available in 37 of 45 (82%) and 41 of 46 (89%) of GroupControl and GroupPrecond donors, respectively, (P = 0.3). Grafts were classified as steatotic (versus nonsteatotic) when macrovacuolar steatosis was observed in >20% of hepatocytes.

OLT Technique

OLT was performed as reported elsewhere. In brief, the native liver was totally removed with caval preservation.32 Temporary portacaval shunt was performed according to the transplant surgeon's preference.33 The whole liver graft was then implanted. Cold ischemia time was considered as the time elapsed from devascularization in the donor until portalreperfusion in the recipient. A liver biopsy was performed before closure of the abdomen to evaluate ischemia-reperfusion injury (postreperfusion biopsy). This was done in 32 of 45 (71%) and 38 of 46 (83%) of GroupControl and GroupPrecond subjects, respectively (P = 0.2). Ischemia-reperfusion injury was classified as moderate to severe (versus absent) when at least 10% of hepatocytes were necrotic, mainly in the center of the lobule or disseminated throughout.5

Postoperative Management

Transplanted patients received a standard immunosuppression regimen of tacrolimus and methylprednisolone. Early outcome was assessed by measuring ischemia-reperfusion liver injury, measured by the peak ASAT concentration; liver function tests, including the minimum prothombin time; and the peak bilirubin concentration and kidney function measured by the peak creatinine concentration. All peak levels and minimum values were recorded within 10 days of transplantation, primary nonfunction (immediate absence of graft function leading to retransplantation or death), and initial poor function (minimal prothrombin value <30% of normal level and/or maximum bilirubin concentration >200 μmol/L after ruling out hemolysis and biliary obstruction), and clinical outcome. For the latter, the following data were recorded: technical complications including hemoperitoneum needing surgery, arterial, portal, outflow and biliary complications. Histologically proven acute rejection was recorded, provided it occurred within 6 weeks of transplantation and needed increased immunosuppression. Postoperative mortality was defined as death occurring during the primary hospitalization period following transplantation.

Data Analysis

All quantitative data are expressed as mean ± SD. A P value <0.05 was considered significant. To be clinically relevant, only data available before transplantation and potentially predictive of the maximum value of ASAT in the recipient within 10 days of transplantation were assessed by univariate analysis. The assessed data included: age and liver function tests of donors and recipients, the length of donors stay in ICU prior to harvesting, the application of ischemic preconditioning, the presence of graft steatosis, and body mass index of the donors. All the patients had a complete data set. If significantly correlated with the end-point, factors were evaluated by regression multivariate analysis. Likewise, only data available before transplantation and potentially predictive of initial poor function were assessed by univariate analysis. As only one factor was found to be significantly correlated with this end-point (see Results), logistical regression was not carried out. Despite the study design, correlation of end-points to specific perioperative data (namely, cold ischemia time, duration of operation, and transfusion requirements) are reported in Results. Survival rates were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and groups were compared with the log-rank test. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Transplant surgeons, biologists, intensive care specialists, and pathologists were not informed whether the graft had been subjected to ischemic preconditioning in the donor.

RESULTS

Donors, Recipients, and Intraoperative Data

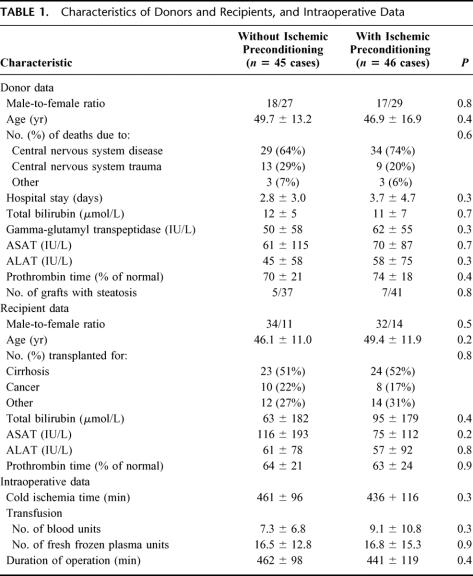

There were no significant differences between the donors, the recipients, and operative data in the 2 groups (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Characteristics of Donors and Recipients, and Intraoperative Data

Analysis of Baseline and Postreperfusion Biopsies

The baseline biopsy revealed steatosis in 5 of 37 (13.5%) and 7 of 41 (17%) available cases in the GroupControl and GroupPrecond, respectively (P = 0.8). The postreperfusion biopsy detected ischemia-reperfusion injury, as defined in the methods section, in 26 of 32 (81%) and 21 of 38 (55%) available cases of GroupControl and GroupPrecond, respectively (P = 0.02).

Analysis of Hospital Mortality, Technical Morbidity, Acute Rejection, and Length of Stay in Intensive Care Unit and Hospital

One of the patients in the GroupControl (2%, due to sepsis) and one of those in the GroupPrecond (2%, due to disseminated toxoplasmosis, P = 0.98) died while in the hospital.

The mean number of technical complications per patient was similar in GroupControl and GroupPrecond (0.2 ± 0.6 versus 0.3 ± 0.6, respectively, P = 0.5). The incidence of hemoperitoneum needing surgery (3 of 45 versus 6 of 46, respectively, P = 0.3), arterial thrombosis (2 of 45 versus 1 of 46, respectively, P = 0.5) and biliary complications (5 of 45 versus 7 of 46, respectively, P = 0.6) were similar in both groups. There were no cases of portal vein thrombosis or outflow block in our series.

Acute rejection rates were similar in the 2 groups (12 of 45 versus 9 of 46 for GroupControl and GroupPrecond, respectively, P = 0.4).

A trend toward a longer hospital stay and a longer stay in intensive care was observed for the GroupPrecond compared with the GroupControl (38 ± 25 versus 31 ± 12 days and 15 ± 14 versus 12 ± 6, respectively); however, this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.1, and P = 0.1, respectively).

Survival

Four patients (2 from each group) died 6, 10, 15, and 21 months after transplantation. No difference in patient survival was found between the groups (98% and 93% at 1 year in GroupControl and GroupPrecond, respectively, P = 0.2, log-rank). The mean follow-up period was 25 ± 13 months; no cases of retransplantation occurred.

Liver Graft Tolerance to Ischemia-Reperfusion

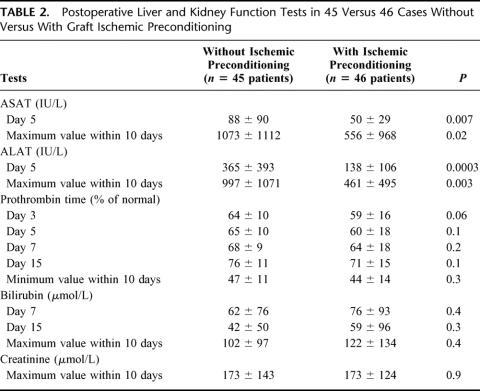

At day 5, patients in GroupPrecond had significantly lower serum ASAT concentrations (50 ± 29 versus 88 ± 90 IU/L, respectively, P = 0.007) and ALAT concentrations (138 ± 106 versus 365 ± 393 IU/L, respectively, P = 0.0003) than those in GroupControl (Table 2). Patients inGroupPrecond had a significantly lower peak ASAT concentration (556 ± 968 versus 1073 ± 1112 IU/L, respectively, P = 0.02) and a significantly lower peak ALAT concentration (461 ± 495 versus 997 ± 1071 IU/L, P = 0.003) than those in GroupControl.

TABLE 2. Postoperative Liver and Kidney Function Tests in 45 Versus 46 Cases Without Versus With Graft Ischemic Preconditioning

Factors Associated With the Maximum ASAT Concentration Within 10 Days of Transplantation

To be clinically relevant, only data available before transplantation were included in univariate and multivariate analyses to identify independent factors affecting the peak ASAT concentration. Three factors were identified in univariate analysis, including ischemic preconditioning (peak value 1073 ± 1112 versus 556 ± 968 IU/L for GroupControl and GroupPrecond, respectively, P = 0.02), presence of graft steatosis (peak value 2132 ± 1716 versus 633 ± 812 IU/L for grafts with and without steatosis respectively, P < 10−3), and the body mass index of the donor (P < 10−3). None of the other factors evaluated were significant; these included age, liver function tests of both the donor and the recipient, and the length of donor's hospital stay prior to harvesting (data not shown). In the multivariate analysis, the same 3 factors remained independently associated with a higher peak of ASAT: preconditioning (P = 0.01), presence of graft steatosis (P <10−3), and the body mass index of the donor (P<10−3).

The peak levels of ASAT and ALAT were not significantly associated with cold ischemia time (P = 0.07, and P= 0.4, respectively), duration of operation (P = 0.09 and P= 0.3, respectively), or intraoperative transfusion need (P= 0.8 and P = 0.6, respectively).

Effect of Liver Graft Preconditioning on Liver and Renal Function

We found no statistically significant difference in serum levels of bilirubin and prothombin time between the 2 groups at any time point (Table 2). However, at all time points, a trend toward a lower prothrombin time and a higher bilirubin level was found in GroupPrecond compared with GroupControl. No cases of primary nonfunction occurred. Initial poor function occurred in 6 (13%) and 15 (33%) patients from GroupControl and GroupPrecond, respectively (P= 0.03).

The maximum creatinine levels within 10 days of transplantation were similar in the 2 groups (P = 0.9).

Factors Associated With Initial Poor Function

Univariate analysis showed that preconditioning was the only pretransplantation factor associated with initial poor function (P = 0.04). None of the other factors tested was significant, including donor's age (P = 0.6), body mass index (P = 0.8), duration of hospital stay (P = 0.5), and liver steatosis (P = 0.3). Likewise, the age (P = 0.7) and creatinine level of the recipient prior to transplantation (P = 0.1) were not significantly associated with initial poor function.

The occurrence of initial poor function was not significantly associated with cold ischemia time (P = 0.7) or duration of operation (P = 0.1). On the contrary, it was significantly associated with intraoperative requirement for transfusion (P = 0.01).

DISCUSSION

This study using the model of cadaveric whole liver transplantation is the first to evaluate the effect of ischemic preconditioning of the graft in humans. In accordance with most animal studies, our results show that ischemic preconditioning protects against ischemia-reperfusion injury as indicated by lower ASAT levels.34 Multivariate analysis showed that ischemic preconditioning was independently predictive of a lower peak ASAT concentration posttransplantation in association with already recognized factors, namely, steatosis of the graft1,5 and the body mass index of the donor.4,35 Ischemic preconditioning did not have the same positive impact on liver function. Indeed, ischemic preconditioning was the only factor significantly associated with initial poor function. There is no universally accepted definition of initial poor function.1,4–6,35–39 Like others, we consider that transaminases reflect the ischemia-reperfusion injury of the liver graft, whereas PT and bilirubin (even though the latter is multifactorial) are the best markers of graft function in clinical practice. The fact that initial poor function was more common in the GroupPrecond than in the GroupControl had no deleterious consequences on patient or graft survival rates in our series. However, it is reasonable to speculate that differences would be found with a much larger sample size as poor initial function is a major pronostic factor following liver transplantation.1,4,8 This is supported by longer stays in intensive care and hospital in GroupPrecond compared with in GroupControl.

The contradictory effect of ischemic preconditioning cannot be confirmed in animal studies as none of them explored the coagulation factors and bilirubin levels after ischemic preconditioning of the liver. However, Adam et al28 showed that preconditioning of the liver graft was associated with altered liver function compared with a control group in a rat model. In the 2 human studies that evaluated the preconditioning-like effect of reversible cardiac arrest in the cadaveric donor, posttransplantation prothrombin time and bilirubin level were similar regardless of whether the donor had sustained temporary cardiac arrest prior to harvesting.29,30 According to the authors, numerous biases, including the duration of cardiac arrest and the delay from cardiac arrest to graft harvesting, preclude the transposition of their observations to the clinical situation of ischemic preconditioning.

It is now established that the occurence of ischemic preconditioning differs between different tissues within a given species and in the same tissue in different species.9,40–43 For example, 2 studies, one using porcine kidneys44 and one using dog kidneys,45 failed to identify renal ischemic preconditioning. These results differ strongly from those obtained in small animal species.40,41,46–48 The many mechanisms of ischemic preconditioning might explain the abovementioned discrepancies;10,11,49 however, this is beyond the scope of our study. We are conscious that biases in our study might explain the negative effect of ischemic preconditioning on liver graft function. These biases include the preconditioning protocol and the choice of study design. Pharmacologic preconditioning protocols that do not include a warm ischemia step (with portal triad clamping) might prevent this negative effect.50,51

Although factors associated with initial poor function have previously been reported, most studies concentrate on donor and perioperative prognostic criteria, including cold ischemia time, duration of operation, and intraoperative transfusion.4 In clinical practice, these data are not available when deciding to transplant a patient with a given liver graft. The objective of this report was to identify factors of prognostic value available at the time when the decision to transplant is taken. Indeed, no correlation was found between the cold ischemia time, the duration of operation, or the transfusion need on the one hand and the peak levels of ASAT and ALAT on the other hand.

In summary, ischemic preconditioning of cadaveric liver grafts protects against ischemia-reperfusion injury. This beneficial effect is counterbalanced by a deleterious effect on the early graft function, with an increased incidence of initial poor function. Our study suggests that warm ischemia triggers the positive effect of preconditioning on ischemia-reperfusion injury but adds its deleterious effect on the liver function to that of cold ischemia.7

CONCLUSION

This first clinical application of ischemic preconditioning of a graft confirms its protective effect against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Preconditioning as performed in our protocol did neither improve nor compromise the outcome of cadaveric liver transpantation. As immediate and sufficient function of the graft is the primary goal of transplantation, the use of ischemic preconditioning, via 10 minutes of warm ischemia, is not appropriate for liver transplantation in clinical practice.

Footnotes

Reprints: Daniel Azoulay, MD, PhD, Centre Hépato-Biliaire, Hôpital Paul Brousse, 94800, Villejuif, France. E-mail: daniel.azoulay@pbr.ap-hop-paris.fr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ploeg RJ, D'Alessandro AM, Knechtle SJ, et al. Risk factors for primary dysfunction after liver transplantation: a multivariate analysis. Transplantation. 1993;55:807–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serracino-Inglott F, Habib NA, Mathie RT. Hepatic-ischemia reperfusion injury. Am J Surg. 2001;181:160–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaeschke H. Mechanism of preservation injury after warm ischemia of the liver. J Hepatol. 1998;21:402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strasberg SM, Howard TK, Molmenti EP, et al. Selecting the donor liver: risk factors for poor function after orthotopic liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1994;20:829–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adam R, Reynes M, Johann M, et al. The outcome of steatotic grafts in liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1991;23:1538–1540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Alessandro AM, Kayaloglu M, Sollinger HW, et al. The predictive value of donor liver biopsies for the development of primary nonfunction after orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1991;51:157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belzer FO, Southard JH. Principles of solid organ preservation by cold storage. Transplantation. 1988;45:673–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adam R, Bismuth H, Diamond T, et al. Effect of extended cold ischemia with UW solution on graft function after liver transplantation. Lancet. 1992;340:1373–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murry CE, Jennings RB, Reimer KA. Preconditioning with ischemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation. 1986;74:1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carini R, Albano E. Recent insights on the mechanisms of liver preconditioning. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1480–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaeschke H. Molecular mechanisms of hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury and preconditioning. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284:G15–G26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pang CY, Yang RZ, Zhong A, et al. Acute ischemia preconditioning protects against skeletal muscle infarction in the pig. Cardiovasc Res. 1995;29:782–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishida T, Yarimizu K, Gute DC, et al. Mechanisms of ischemic preconditioning. Shock. 1997;8:86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonventre JV. Kidney ischemic preconditioning. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2002;11:43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirino T. Ischemic tolerance. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:1283–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Du ZY, Hicks M, Winlaw D, et al. Ischemic preconditioning enhances donor lung preservation in the rat. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1996;15:1258–1267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Selzner N, Rüdiger H, Graf R, et al. Protective strategies against ischemic injury of the liver. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:917–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clavien PA, Yadav S, Sindram D, et al. Protective effects of ischemic preconditioning for liver resection performed under inflow occlusion in humans. Ann Surg 2000;232:155–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clavien PA, Selzner M, Rüdiger HA, et al. A prospective randomized study in 100 consecutive patients undergoing major liver resection with versus without ischemic preconditioning. Ann Surg. 2003;238:843–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nuzzo G, Giugliante F, Vellone M, et al. Pedicle clamping with ischemic preconditioning in liver resection. Liver Transpl. 2004;10(suppl):53–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cleveland JC, Raeburn C, Harken AH. Clinical applications of ischemic preconditioning: from head to toe. Surgery. 2001;129:664–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raeburn CD, Cleveland JC, Zimmerman MA, et al. Organ preconditioning. Arch Surg. 2001;136:1263–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arai M, Thurman RG, Lemasters JJ. Ischemic preconditioning of rat livers against cold storage-reperfusion injury: role of nonparenchymal cells and the phenomenon of heterologous preconditioning. Liver Transplantation. 2001;7:292–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lloris-Carsis JM, Cejalvo D, Toledo-Pereyra LH, et al. Preconditioning: effect upon lesion modulation in warm liver ischemia. Transplant Proc. 1993;25:3303–3304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kume M, Yamamoto Y, Saad S, et al. Ischemic preconditioning of the liver in rats: implications of heat shock protein induction to increase tolerance of ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Lab Clin Med. 1996;128:251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peralta C, Hotter C, Closa D, et al. Protective effect of perconditioning on the injury associated to hepatic ischemia-reperfusion in the rat: role of nitric oxide and adenosine. Hepatology. 1997;25:934–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yin DP, Sankary HN, Chong ASF, et al. Protective effect of ischemic preconditioning on liver preservation-reperfusion injury in rats. Transplantation. 1998;66:152–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adam R, Arnault I, Bao YM, et al. Effect of ischemic preconditioning on hepatic tolerance to cold ischemia in the rat. Transpl Int. 1998;11(suppl):168–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Totsuka E, Fung JJ, Urakami A, et al. Influence of donor cardiopulmonary arrest in human liver transplantation: possible role of ischemic preconditioning. Hepatology. 2000;31:577–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson DJ, Fisher A, Das K, et al. Donors with cardiac arrest: improved organ recovery but no preconditioning benefit in liver allografts. Transplantation. 2003;75:1683–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Starzl TE, Miller C, Broznick B, et al. An improved technique for multiple organ harvesting. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1987;1656:343–348. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Calne RY, William R. Transplantation in man: I. Observations on technique and organization in five cases. Br Med J. 1968;4:535–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belghiti J, Panis Y, Sauvanet A, et al. A new technique of side to side caval anastomosis during orthotopic hepatic transplantation without inferior vena caval occlusion. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1992;175:271–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iu S, Harvey P, Makowka L, et al. Markers of allograft viability in the rat: relationship between transplantation viability and liver function in the isolated perfused rat liver. Transplantation. 1987;45:562–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mor E, Klintmalm GB, Gonwa TA, et al. The use of marginal donors for liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1992;53:383–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strasberg SM. Preservation injury and donor selection: it all starts here. Liver Transpl Surg 1997;5(suppl):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Makowka L, Gordon RD, Todo S, et al. Analysis of donor criteria for the prediction of outcome in clinical liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1987;19:2378–2382. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Howard TK, Goran B, Klintmalm G, et al. The influence of preservation injury on rejection in the hepatic transplant recipient. Transplantation. 1990;49:103–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greig PD, Forster J, Superina RA, et al. Donor-specific factors predict graft function following liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1990;22:2072–2073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park KM, Chen A, Bonventre JV. Prevention of kidney ischemia/reperfusion-induced functional injury and JNK, p38, and MARK kinase activation by remote ischemic pretreatment. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1870–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turman MA, Bates CM. Susceptibility of human proximal tubular cells to hypoxia: effect of hypoxic preconditioning and comparison to glomerular cells. Renal Failure. 1997;19:47–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berhends M, Walz MK, Kribben A, et al. No protection of the porcine kidney by ischaemic preconditioning. Exp Physiol. 2000;85:819–827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jefayri MK, Grace PA, Mathie RT. Attenuation of reperfusion injury by renal ischaemic preconditioning: the role of nitric oxide. Br J Urol Int. 2000;85:1007–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arend LJ, Thompson CI, Spielman WS. Dypiramidol decreases glomerular filtration in the sodium-depleted dog: evidence for mediation by intrarenal adenosine. Circ Res. 1985;56:242–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kosieradzki M, Ametani M, Southard JH, et al. Is ischemic preconditioning of the kidney clinically relevant? Surgery. 2003;133:81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cochrane J, Williams BT, Banerjee A, et al. Ischemic preconditioning attenuates functional, metabolic, and morphologic injury from ischemic renal failure in the rat. Renal Failure. 1999;21:135–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Islam CF, Mathie RT, Dinneen MD, et al. Ischaemia-reperfusion injury in the rat kidney: the effect of preconditioning. Br J Urol. 1997;79:842–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pagliaro P, Gattullo D, Rastaldo R, et al. Ischemic preconditioning: from the first to the second window of protection. Life Sci. 2001;69:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sakon M, Ariyoshi H, Umeshita K, et al. Ischemia-reperfusion injury of the liver with special reference to calcium-dependent mechanisms. Surg Today. 2002;32:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mokuno Y, Berthiaume F, Tompkins RG, et al. Technique for expanding the donor liver pool: heat shock preconditioning in a rat fatty liver model. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:264–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Glanemann M, Strenziok R, Kuntze R, et al. Ischemic preconditioning and methylprednisolone both equally reduce hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury. Surgery. 2004;135:203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]