Abstract

Glycoprotein B (gB) of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), which is considered essential for the viral life cycle, is proteolytically processed during maturation. Since gB homologues of several other herpesviruses remain uncleaved, the relevance of this property of HCMV gB for viral infectivity is unclear. Here we report on the construction of a viral mutant in which the recognition site of gB for the cellular endoprotease furin was destroyed. Because mutagenesis of essential proteins may result in a lethal phenotype, a replication-deficient HCMV gB-null genome encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein was constructed, and complementation by mutant gBs was initially evaluated in transient-cotransfection assays. Cotransfection of plasmids expressing authentic gB or gB with a mutated cleavage site (gB-ΔFur) led to the formation of green fluorescent miniplaques which were considered to result from one cycle of phenotypic complementation of the gB-null genome. To verify these results, two recombinant HCMV genomes were constructed: HCMV-BAC-ΔMhdI, with a deletion of hydrophobic domain 1 of gB that appeared to be essential for viral growth in the cotransfection experiments, and HCMV-BACΔFur, in which the gB cleavage site was mutated by amino acid substitution. Consistent with the results of the cotransfection assays, only the ΔFur mutant replicated in human fibroblasts, showing growth kinetics comparable to that of wild-type virus. gB in mutant-infected cells was uncleaved, whereas glycosylation and transport to the cell surface were not impaired. Extracellular mutant virus contained exclusively uncleaved gB, indicating that proteolytic processing of gB is dispensable for viral replication in cell culture.

Glycoprotein B (gB) homologues are highly conserved within the herpesvirus family. In most herpesviruses they are prominent components of the viral envelope which are involved in virus attachment, penetration, and cell-to-cell spread (12). Structural analyses have revealed common properties of gB homologues: they are type 1 transmembrane glycoproteins with additional internal hydrophobic domains in the lumenal portion (43), they have an extended cytoplasmic tail which may be relevant for fusogenicity (5, 53), and they are dimerized by disulfide bonding (11). On the other hand, there are differences in maturational processing, and it is presently not well understood how the structure of gB molecules is related to their biological function.

Several gB homologues carry the specific cleavage motif RXK/RR, which is the recognition motif for proteolytic processing by the cellular endoprotease furin (11, 22, 26, 32, 35, 44, 48, 50, 51), e.g., the gB homologues of varizella-zoster virus, bovine herpesvirus type 1 (BHV-1), pseudorabies virus (PRV), equine herpesvirus, Marek’s disease virus, and all known betaherpesviruses, including human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) and human herpesvirus 6. In contrast, there are members of the herpesvirus group that harbor gB homologues without this specific furin cleavage site, e.g., Epstein-Barr virus (23), herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2) (16, 19), and simian herpesvirus B.

For gB proteins of the alphaherpesviruses BHV-1 and PRV, it has been shown that virions in which cleavable gB is replaced by an uncleavable homologue maintain the potential to replicate in cell culture (30). Other cross-complementation studies revealed that PRV gB, which is proteolytically processed during viral infection, was able to complement an HSV gB null mutant, but uncleaved HSV gB was not competent to replace PRV gB in the respective null mutant (37). Moreover, by replacement of the gB protein in an alpha- or gammaherpesvirus with homologues from a different subfamily, functional complementation was apparently not achieved (31). These observations indicate that gB homologues, despite their structural conservation, carry out unique functions within their respective viral contexts.

In virus families other than herpesviruses, proteolytic processing of envelope proteins is known to be pivotal for activation of viral infectivity. This has been shown for, e.g., influenza viruses (29) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (33). In these cases the specific cleavage process takes place during maturational cellular transport of the membrane protein through the trans-Golgi network and produces two fragments, a membrane-anchored and a distal lumenal product that usually remain associated, e.g., by disulfide bonds. Characteristically, the processed membrane-anchored fragment exhibits a terminal lumenal domain with hydrophobic properties. After integration of the mature protein into the plasma membrane or the viral envelope, this terminal domain serves as a fusion peptide for interaction with target membranes, while the distal fragment serves as a ligand for host cell receptor binding.

In the case of HCMV gB, the relevance of proteolytic processing for viral infectivity remains to be shown, for there are obvious structural differences compared to influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) and the HIV envelope protein. First, the latter two form a trimeric complex in the plane of the membrane (52, 54), whereas dimers have been found for HCMV gB (10). Second, the hydrophobic domain in the c-terminal gB fragment is slightly longer than the classical fusion peptide described for HA and located at a distance of 255 amino acids from the cleavage site. Third, influenza virus, e.g., enters the host cell via receptor-mediated endocytosis, and fusion processes mediated by HA are a result of conformational changes induced by change of the ionic environment within endocytic vesicles. In contrast, HCMV, like HIV, enters the cell by direct, pH-independent fusion with the plasma membrane. If proteolytic processing plays a role in fusogenic activation of HCMV gB, a different model has to be assumed.

The direct approach to determining the functional role of HCMV gB cleavage for viral infectivity by the use of appropriate viral mutants has now become possible by the achievement of cloning the entire HCMV genome as a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) (7). In this study, a replication-deficient gB-null BAC (BACΔgB) encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein was generated and used for cotransfection with expression constructs encoding gB proteins carrying defined mutations. This approach was taken to screen for transiently expressed gB forms that were competent to complement the viral null mutant and was expected to result in formation of green fluorescent miniplaques if phenotypical complementation occurred. The observation that uncleavable gB supported miniplaque formation in this assay was consecutively verified by introduction of the mutations into the HCMV genome and by partial characterization of the viable viral progeny.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus and cells.

Human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF) and human embryonic lung cells (MRC-5; ATCC CCL-171) were cultivated in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mM l-glutamine, and 50 U each of penicillin and streptomycin per ml. The HCMV strain RVHB5 used in this study as a control for analysis of growth kinetics was obtained after transfection of MRC-5 with recombinant HCMV BAC plasmid pHB5 (7).

For the preparation of virus stocks, HFF or MRC-5 were infected at a multiplicity of infection of <0.01 and incubated in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C for about 7 to 10 days until the cytopathic effect was complete. Supernatants were collected, cleared by centrifugation for 10 min at 2,000 rpm, and stored in aliquots at −80°C. For analysis of growth kinetics of viral mutants, six-well cultures of HFF were infected 24 h after seeding (5 × 105 cells/well) in triplicate at a multiplicity of infection of 0.1. At various time intervals after infection, aliquots were taken from the culture medium for titration of infectious virus by plaque assay on HFF or MRC-5 as described previously (7).

BAC isolation.

Small amounts of BAC plasmid DNA were isolated by standard alkaline lysis procedure (45) from 10-ml overnight cultures. Large-scale BAC plasmid preparations were obtained from 500-ml overnight cultures using Nucleobond PC500 columns (Macherey Nagel, Düren, Germany) according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

gB expression plasmids.

Construction and eukaryotic expression of plasmids pRC/CMVgB (42), pRC/CMVgB(Del1), pRC/CMVgB(Del2), pRC/CMVgB(Del3), pRC/CMVgB(Del4), pRC/CMVgB(Del5) (5), pRC/CMVgB(MhdI), pRC/CMVgB(MhdII) (43), and pRC/CMVgB(sINM) (formerly HCMV gB 885D-A, 886R-A, 889H-E, and 890R-E) (38) were described previously. Plasmid pRC/CMVSigDelgB was constructed by overlapping PCR using pRC/CMVgB as a template. The fragment upstream of the signal peptide sequence was amplified using oligonucleotides SigDelgB1T and SigDelgB2T (for oligonucleotides, see Table 1). The fragment downstream of the signal peptide sequence was amplified with oligonucleotides SigDelgB3T and SigDelgB4T. The oligonucleotides SigDelgB2T and SigDelgB3T contain a 5′ overhanging region of 22 bp that are complementary to each other. A third PCR was performed using the PCR products of the first two reactions as a template and the outer oligonucleotides SigDelgB1T and SigDelgB4T, generating a gB-encoding fragment which lacks the sequences for the signal peptide.

TABLE 1.

Nucleotide sequences of primers used for generation of recombination constructsa

| Primer | Sequence | Genomic position(s) (nt) |

|---|---|---|

| bac2 5′ | 5′-GACTGAATTCCCTGTGTATCGTCTGTCTGGGTGCTGC-3′ | 83428–83454 |

| bac2 3′ | 5′-CTACCTCGAGTTCGAAGACGGACACGTTTCC-3′ | 82227–82247 |

| gB-(Fur)A | 5′-CAGTCTGAATATCACTCATGCGACCCGGGCAAGTACGAGTGAC-3′ | 82104–82146 |

| gB-(Fur)B | 5′-GTCACTCGTACTTGCCCGGGTCGCATGAGTGATATTCAGACTG-3′ | 82104–82146 |

| gB-L.for | 5′-GCGTACGTGATGAGGCTATAAATAAGTTACAGCAGATTTTCAATACT TCATACAATCAAACACTACAAGGACGACGACGACAAGTAA-3′ | 82260–82321 |

| gB-L.rev | 5′-GTCTGACCGTCGAACATGACACCTCGCGGCACGATCTGCAAAAACTG TTTCTGTGGCGGCCGTGACACAGGCACACTTAACGGCTGA-3′ | 80468–80529 |

| HomB XbaI | 5′-CAATCTAGACGCGCACCGAAGCACGCACAAAGC-3′ | 78317–78347 |

| pgB/L | 5′-CGACTTTGATGATGGCCAGCAACA-3′ | 84670–84693 |

| pgB/R | 5′-ATTAGGATCCAGGTTAACGCAGACTACCAGG-3′ | 83451–83472 |

| ResFur3 | 5′-CACTTGAAAGACTCCGACGAAGAAGAGAACGTCTGA-3′ | 80772–80807 |

| RevSigDelgB | 5′-CTGGACAAATGAGTTGTATTATTGTCACTC-3′ | 82081–82110 |

| SigDelgB1T | 5′-CACTATAGGGAGACCCAAGCTTGGTACCG-3′ | 874–902* |

| SigDelgB2T | 5′-GTACTAGAAGACATGTTCGTCGCGGGCCAAATCCAG-3′ | 83410–83420, 83490–83514 |

| SigDelgB3T | 5′-CGACGAACATGTCTTCTAGTACTTCCCATGCAACTTCTTCTACTCAC-3′ | 83386–83420, 83490–83500 |

| SigDelgB4T | 5′-GAGTGATATTCAGACTGGATCGATTGGCC-3′ | 82130–82158 |

Restriction enzyme sites are underlined, sequences that are not present on the HCMV genome are in italics. Genomic position refers to the position in the published sequence of the HCMV AD169 genome (14). *, position in plasmid pRC/CMV.

The resulting PCR product and plasmid pRC/CMVgB were digested with endonucleases HindIII and ClaI, and the original fragment was replaced by the SigDelgB fragment. Plasmid pRC/CMVgBΔFur was constructed using the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Promega, Madison, Wis.) following the instructions of the supplier. The primers used were gB-(Fur)A and gB-(Fur)B, which destroy the furin cleavage site in gB by changing the recognition sequence from Arg-Thr-Arg-Arg (RTRR) to Ala-Thr-Arg-Ala (ATRA). In addition, a new SmaI restriction site was introduced into the gB gene by the mutagenesis reaction.

Plasmids for BAC mutagenesis.

For generation of the replication-deficient BAC plasmid BACΔgB, plasmid bac2_3frt was constructed. To this end, a fragment coding for the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) was isolated from plasmid pEGFP (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.) and inserted between the BamHI and EcoRI sites of vector pIREShyg (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.). Subsequently, a fragment containing the gB promoter was amplified using oligonucleotides pgB/L and pgB/R. The template for PCR amplification was plasmid pUC18 54H56 (47), a pUC18 derivative that contains a 1,350-bp fragment upstream of the gB open reading frame (ORF) (nucleotides [nt] 83455 to 84805) (14). In the resulting amplified fragment, the start codon of the gB ORF was disrupted. The amplified fragment was cut with endonucleases NruI and BamHI, resulting in a 1,251-nt fragment (nt 77299 to 76275) (14) that was inserted between the NruI and BamHI sites of the vector.

Oligonucleotides bac2 5′ and bac2 3′ served for amplification of a DNA fragment corresponding to nt 88454 to 82227 of the HCMV genome (14), and the template for amplification was pCM1029 (22). The amplificate was cut with EcoRI and XhoI and inserted into the vector following digestion with the same enzymes. To complete construction of plasmid bac2_3frt, a fragment coding for kanamycin resistance was excised from plasmid pCP15 (15), in which the resistance marker is flanked by two Flp recombination target sites (FRT) and inserted into the vector that had been linearized by XbaI digestion and refilled by treatment with the Klenow fragment.

The shuttle plasmids for construction of the two-step BAC mutagenesis vectors needed for site-directed deletion of the furin cleavage site and hydrophobic domain one (Mhd1) of gB were generated as follows. Vector pUC18 (Invitrogen, Leek, The Netherlands) was linearized by NdeI digestion, and the single-stranded 5′-overhanging ends were refilled and religated. The fragment between the HindIII and the EcoRI sites of pUC18 was excised and replaced by an oligonucleotide linker (StuI-NruI-NdeI-NotI-XbaI-NheI-StuI). In the following step, a fragment containing nt 84457 to 82259 (14) of the HCMV genome was excised from pRC/CMVgBP by FspI and NdeI digestion and inserted into the NruI and NdeI sites of modified pUC18.

pRC/CMVgBP is a derivative of pRC/CMVgB containing an HCMV genomic fragment comprising ORF UL55 and its promoter sequence (nt 80524 to 84470) (14). It was obtained by amplification of the gB promoter sequence with oligonucleotides pgBL and RevSigDelgB using pCM1029 as a template. The amplificate was cut with endonucleases NruI and HpaI and inserted into the HpaI-digested vector pRC/CMVgB. The second region (nt 80525 to 78317) needed for homologous recombination (14) was amplified using oligonucleotides ResFur3 and HomB XbaI with template pCM1029 and inserted between the NotI and XbaI sites of the polylinker, resulting in plasmid pUC18AB. The two DNA fragments between the restriction sites NdeI and NotI carrying the desired mutations in gB were excised from plasmids pRC/CMVgBΔFur and pRC/CMVgB(MhdI) and inserted into plasmid pUC18AB to generate plasmids pUC18ABΔFur and pUC18ABΔMhdI, respectively.

To facilitate further cloning steps, a tetracycline resistance gene was excised from plasmid pBR322 (Invitrogen, Leek, The Netherlands) by restriction endonucleases HindIII and StyI for insertion into vectors pUC18ABΔFur and pUC18ABΔMhdI. Following linearization of the vectors by NheI digestion and refilling of 5′-overhanging ends of all fragments by Klenow fragment treatment, ligation was carried out to obtain plasmids pUC18ABΔFur-tet and pUC18ABΔMhdI-tet. Fragments of about 7.5 kb carrying the mutations, the regions needed for homologous recombination, and the tetracycline resistance gene were excised by StuI digestion and inserted into shuttle plasmid pST76K_SR (7), a derivative of pST76K (8, 40), following linearization by SmaI treatment. The resulting recombination plasmids pST76K_SRΔFur and pST76K_SRΔMhdI served for subsequent BAC mutagenesis (see below).

BAC mutagenesis.

Replication-deficient HCMV BACΔgB for the cotransfection assay was constructed as follows (Fig. 1A). The linear recombination fragment needed for mutagenesis (8) was excised from plasmid bac2_3frt by DraIII and NspV digestion and electroporated into Escherichia coli JC8679 (recBC sbcA) harboring parental BAC plasmid pHB5 (8). Bacterial clones were selected on agar plates containing kanamycin (25 μg/ml) plus chloramphenicol (17 μg/ml), and recombined HCMV BAC plasmids were analyzed by restriction enzyme analysis and agarose gel electrophoresis as described previously (7). The kanamycin resistance marker was subsequently removed by site-specific recombination in E. coli using Flp recombinase (1, 8, 15).

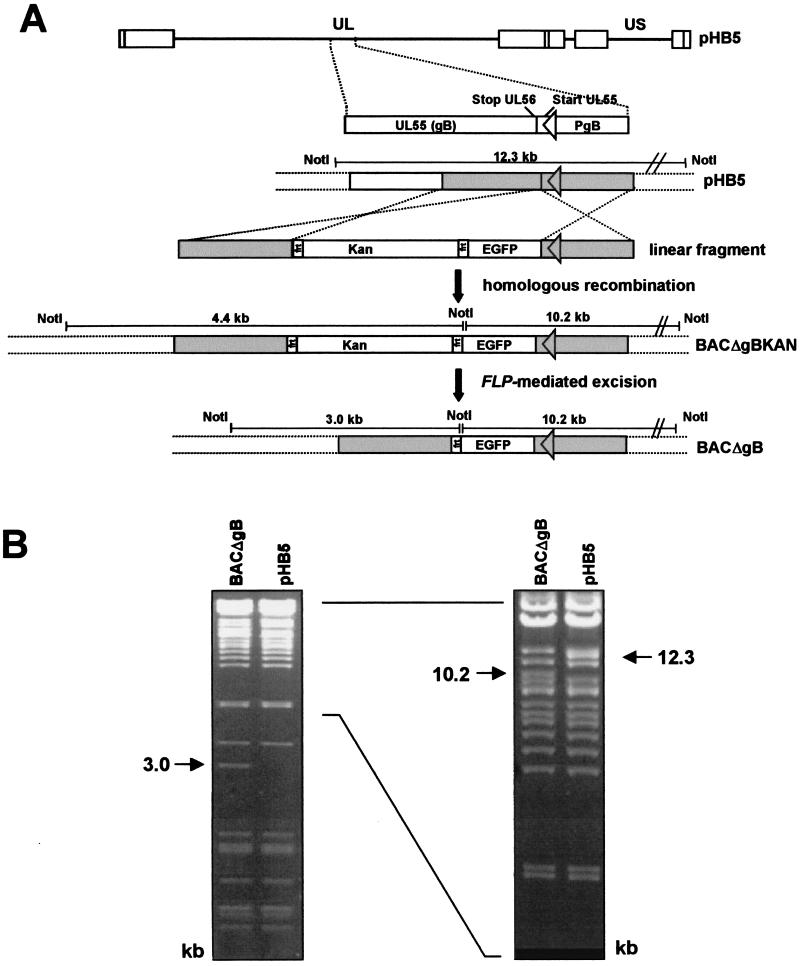

FIG. 1.

Construction and analysis of the replication-deficient BACΔgB. (A) The top line represents the genome structure of parental HCMV BAC pHB5 (pHB5). The region containing ORF UL55 (gB) and its promoter region (PgB) is expanded below. The coding sequences of the EGFP and the kanamycin resistance marker (Kan) provided on a linear NdeI fragment of plasmid bac2_3frt (linear fragment) were inserted immediately downstream of the stop codon of UL56 via homologous recombination as described in Materials and Methods, resulting in BACΔgBKAN. The kanamycin resistance gene was subsequently removed by Flp recombinase-mediated recombination, leading to BAC plasmid BACΔgB. The sizes of the NotI fragments are indicated in kilobase pairs. (B) DNA of BAC plasmids pHB5 and mutant BACΔgB was digested with NotI, separated for 16 h on a 0.8% agarose gel (left panel), and stained with ethidium bromide. To visualize the higher-molecular-weight bands, the identical agarose gel was subjected to electrophoretic separation for an additional 6 h and documented again (right panel). Relevant DNA bands characteristic of BAC plasmids pHB5 and BACΔgB are indicated by arrows, and their sizes are given in kilobase pairs.

HCMV BAC plasmids with mutation of the furin cleavage site or deletion of MhdI were constructed as follows (see Fig. 3). First, the genomic region between the NdeI and NotI sites within the gB ORF (nt 82260 to 80524) was deleted from parental BAC plasmid pHB5. To introduce this mutation, a PCR fragment was generated using the primers gB-L.for and gB-L.rev, which contain about 25 nt, for amplification of the kanamycin resistance gene from vector pACYC177 (13) and an additional 60 nt homologous to the regions flanking the NdeI site and the NotI site of gB, respectively. The resulting fragment was used for mutagenesis with PCR-generated linear fragments (ET mutagenesis) of BAC plasmid pHB5 as described previously (8). Subsequent removal of the kanamycin resistance marker was performed as described above, resulting in BAC plasmid BAC-gBL.

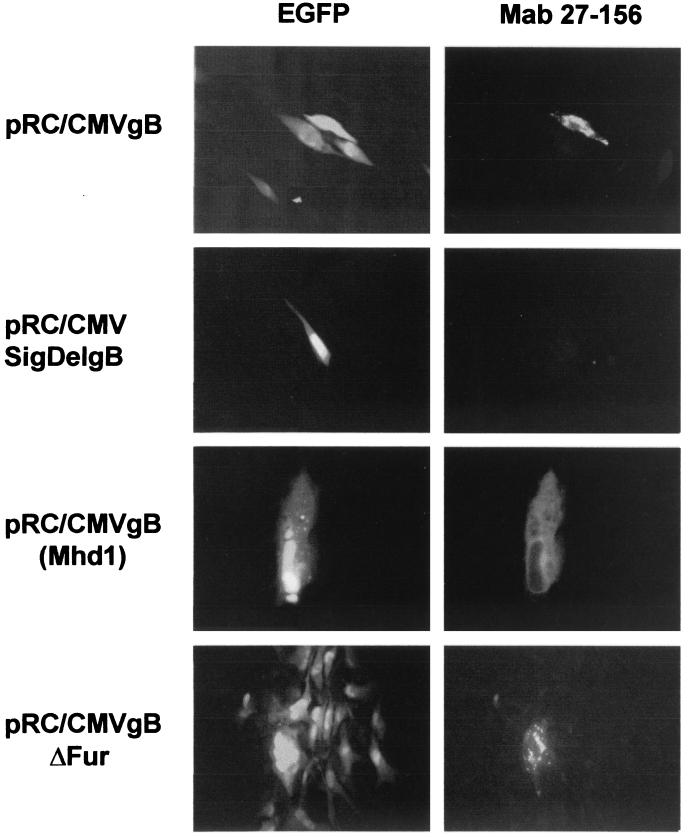

FIG. 3.

Expression of the gB protein in cotransfected cells. Human fibroblast cultures were cotransfected with replication-deficient BACΔgB and gB expression constructs pRC/CMVgB, pRC/CMVSigDelgB, pRC/CMVgB(MhdI), and pRC/CMVgBΔFur. Eight days posttransfection, cells were subjected to indirect immunofluorescence with MAb 27-156 specific for gB (right panel) and examined for expression of EGFP (left panel).

Introduction of the ΔFur and ΔMhdI mutations was performed by a two-step replacement mutagenesis procedure as described previously (7, 36). Briefly, shuttle plasmids pST76K_SRΔFur and pST76K_SRΔMhdI were electroporated into E. coli DH10B containing BAC-gBL. Cointegrates formed between the BAC plasmid and the shuttle plasmid were selected by cultivation on agar plates containing chloramphenicol (17 μg/ml) and kanamycin (30 μg/ml) at 43°C. To allow resolution of the cointegrates, bacteria were streaked onto new plates containing chloramphenicol and incubated at 37°C. Clones that had resolved their cointegrates were selected by incubation on plates containing chloramphenicol plus 5% sucrose and subsequently tested for the resulting sensitivity to kanamycin. Recombined BAC plasmids were further analyzed by endonuclease digestion.

Reconstitution of HCMV BAC virus.

MRC-5 cells were split at a 1:1.2 ratio and seeded into six-well dishes 1 day before transfection. Then 1 μg of BAC DNA and 1 μg of plasmid pCDNA3.1App71tag (2) were cotransfected using a calcium phosphate precipitation technique (MBS mammalian transfection kit; Stratagene, Cedar Creek, Calif.) following the instructions of the manufacturer with slight modifications. The volume of medium added to the cells prior to incubation was reduced to 800 μl/well. After 4 h, the transfection medium was removed and cells were subjected to a glycerol shock (25 mM HEPES, 0.75 mM Na2HPO4, 140 mM NaCl, and 20% [wt/vol] glycerol [pH 7.13], 4°C) for 2 min. Cells were washed twice with DMEM and overlaid with 4 ml of DMEM-10% FCS for incubation at 37°C in a humidified CO2 incubator. Seven days after transfection cells were trypsinized and seeded into 25-cm2 flasks until plaques appeared. The supernatant was used for infection of fresh HFF cultures and preparation of virus stocks.

Cotransfection assay.

For cotransfections, 1 μg of BACΔgB DNA, 1 μg of pcDNApp71tag, and 3 μg of gB expression plasmid were subjected to calcium phosphate transfection as described above. The control consisted of transfections with BACΔgB and plasmid pRC/CMVgB alone, 1 μg pCDNApp71tag was added, and the DNA amount was adjusted to a total of 5 μg by addition of salmon sperm DNA. Transfections were performed in 24-well dishes with cover slips. Each transfection reaction was distributed equally among four wells. Two days after transfection, the cells in one well of each reaction were fixed with ice-cold ethanol-acetone solution (1:1) for 5 min, and the transfection efficiency for the BAC plasmid was determined by indirect immunofluorescence using an HCMV immediate-early antigen (IE)-specific monoclonal antibody (DuPont, Brussels, Belgium). Only samples with >40 IE antigen-positive nuclei/μg of BAC DNA were subjected to further analysis.

Eight days after transfection, another two cover slips were removed, fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 min at room temperature and analyzed with a Zeiss microscope (Axiophot) for the appearance of green fluorescent miniplaques. The fourth cover slip of each reaction was incubated for an additional 3 weeks to examine if genetic rescue had occurred that would give rise to a replication-competent viral rescuant.

All gB expression plasmids were tested at least twice. In some cases an additional immunofluorescence assay for detection of gB was performed. To this end, cells were permeabilized after fixation with 3% PFA for 5 min in 0.2% Triton X-100 and incubated with the gB-specific monoclonal antibody (MAb) 27-156 (kindly provided by W. Britt, Alabama) followed by incubation with a rhodamine-labeled secondary antibody (Dako, Hamburg, Germany).

To demonstrate released phenotypically complemented virus, supernatants of exemplary cotransfections were harvested 2 weeks after transfection, clarified by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 10 min, and distributed onto two parallel cultures of fresh fibroblasts grown in 24-well dishes containing cover slips. One of these cultures was fixed 48 h after transfer of supernatant with ice-cold ethanol-acetone solution and subjected to indirect immunofluorescence using HCMV IE-specific monoclonal antibody. The other infected culture was observed for an additional 2 weeks for possible spread of infectious virus. As a positive control, supernatants derived from parallel transfections of EGFP-encoding wild-type CMV GFP BAC (6) were used.

Immunoblotting and endoglycosidase digestion.

For immunoblotting, extracts of cells or virions were prepared in lysis buffer (3), separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and blotted on nitrocellulose followed by incubation with monoclonal antibody 58-15 (kindly provided by W. Britt, Alabama) and a horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibody (Dako) prior to detection using the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). For the removal of mannose-rich and complex carbohydrate modifications, endoglycosidase H (EndoH) and N-glucosidase F (PNGase F), respectively, were used (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) according to the instructions of the supplier.

RESULTS

Construction of the replication-deficient BACΔgB.

The gB of HCMV was found to be essential for viral growth (28). Accordingly, mutations in domains of the gB protein may easily result in a lethal phenotype. As a first test, we therefore decided to examine the ability of mutant gB proteins to complement an HCMV gB-null mutant in a transient-cotransfection assay. To this end, a replication-deficient HCMV gB-null mutant in which the gB gene was functionally disrupted was constructed on the basis of the parental BAC pHB5.

In order to facilitate monitoring of complementation events by transiently expressed gB proteins, the genome of the gB-null mutant was also supplied with the EGFP marker (Fig. 1A). The ORFs of gB (UL55) and of the neighboring protein p130 (4) (UL56) have an overlapping region of 38 nt, the p130 stop codon being localized within the coding sequence of gB (Fig. 1A). In order to avoid disruption of ORF UL56, the EGFP gene was inserted immediately downstream of the p130 stop codon. To ensure that the EGFP start codon was used for marker expression, the remaining gB start codon was inactivated by mutagenesis (ATG → ACG), thereby simultaneously introducing a silent mutation into the p130 gene. The desired mutations were introduced by homologous recombination in E. coli using plasmid bac2_3frt and BAC plasmid pHB5 as described in Materials and Methods. In the resulting BACΔgB, expression of the EGFP marker is driven by the gB promoter and expression of the gB gene is disrupted (Fig. 1A).

The mutant BACΔgB and parental BAC pHB5 were analyzed by NotI digestion, and the fragment patterns were compared. In BACΔgB the 12.3-kb fragment of pHB5 has disappeared and two new fragments of 10.2 and 3.0 kb were found (Fig. 1B). The restriction patterns showed that the intended modifications had been introduced into the BAC plasmid.

Complementation of BACΔgB by transiently expressed gB forms.

Transfection of the BAC plasmid BACΔgB alone into human fibroblasts led to the formation of single green fluorescent cells only (Fig. 2B, a), indicating that the HCMV genome of BACΔgB allowed expression of the marker gene but did not give rise to infectious particles that can infect neighboring cells. It was expected that after cotransfection with an expression plasmid carrying the authentic gB gene, the transiently expressed gB protein will result in phenotypic complementation. As a consequence, packaging of the BACΔgB DNA, maturation, and release of phenotypically complemented viral progeny would occur in cells that harbor the gB-null genome and the gB expression plasmid.

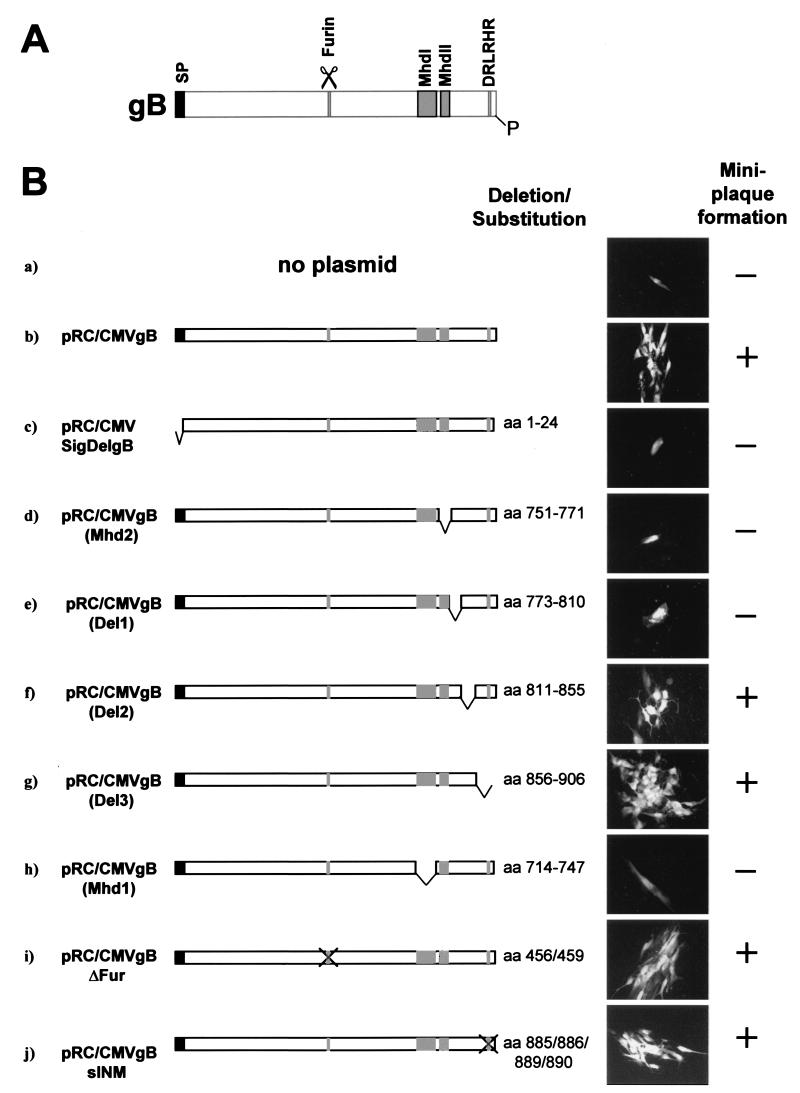

FIG. 2.

Determination of lethal and nonlethal mutations in the gB gene. (A) Schematic presentation of gB. The relative locations of various functional domains are indicated, the signal peptide (SP) by a black bar, the furin cleavage site by scissors, the hydrophobic domains MhdI and MhdII by light grey bars, the localization signal for the inner nuclear membrane by DRLRHR, and the phosphorylation site at amino acid 900 by P. (B) Human fibroblast cultures were cotransfected with replication-deficient BACΔgB and one of the gB expression constructs. The designations of the expression constructs used are given on the left under b to j, and the relative locations of the deletions or substitutions are shown by the schemes. Deleted or substituted amino acids are indicated on the right. On the right panels, micrographs are presented that were taken at 8 to 10 days posttransfection, when cells were examined for the appearance of green fluorescent single cells (miniplaque formation negative, −) or the formation of green fluorescent miniplaques (miniplaque formation positive, +).

Released viral particles should be competent to abortively infect the neighboring cells. Due to the expression of the fluorescent marker, this event could be microscopically monitored by the formation of green fluorescent miniplaques. However, because the abortively infected cells do not contain the gB expression plasmid and do not express gB, no further release of infectious particles and no spread of the infection will occur.

In cells cotransfected with BACΔgB and pRC/CMVgB expressing wild-type gB protein, 8 to 10 days after cotransfection green fluorescent miniplaques appeared (Fig. 2B, b). The plaque numbers in the cotransfection experiments ranged from 2 to 30 per transfection reaction. The miniplaques did not expand and degenerated within 14 to 21 days after appearance. This result is consistent with the expectation that the transiently expressed gB protein complements the gB-null mutant for one cycle of replication.

One portion of each transfection reaction was examined over a 3-week period. Further spread of the infection was never observed. Thus, genetic rescue of the gB-null mutation by reinsertion of the authentic gB gene into the BAC construct is unlikely and cannot be the reason for the miniplaque formation. However, when samples of supernatants of cotransfections that had led to miniplaque formation were harvested and used for the infection of fresh fibroblasts, HCMV IE antigen could be detected in single cells by indirect immunofluorescence (Table 2), indicating that these supernatants contained infectious viral particles. No spread of replication-competent virus was observed, suggesting that the single IE antigen-positive cells recognized were abortively infected with phenotypically complemented virus. The number of IE-positive cells obtained after transfer of supernatants varied for the various identical experimental setups (at least three for each of the cotransfections listed in Table 2) that were performed.

TABLE 2.

Determination of infectious HCMV in supernatants of transfected cultures

| Construct(s) | Single green fluorescent cellsa | Green fluorescent miniplaquesb | IE antigen in single cells after inoculation of HFFc | Multiplication in HFFd |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMV GFP BAC | + | + | + | + |

| HCMV-BACΔgB + pRC/CMVgB | + | + | + | − |

| HCMV-BACΔgB + pRC/CMVSigDelgB | + | − | − | − |

| HCMV-BACΔgB | + | − | − | − |

| pRC/CMVgB | − | − | − | − |

Indicative of successful transfection of replication-deficient HCMV-BACΔgB.

indicative of successful phenotypic complementation of replication-deficient HCMV-BACΔgB for one round of viral replication.

Indicative of release of phenotypically complemented replication-deficient HCMV-BACΔgB competent to abortively infect single cells (10 to 50 HCMV -IE-positive nuclei/ml of supernatant).

Indicative of replication-competent HCMV.

As a negative control for the complementation assay, expression plasmids encoding gB with a deletion of the signal peptide (pRC/CMVSigDelgB) (Fig. 2B, c), or gB with a deletion of the membrane anchor [pRC/CMVgB(MhdII)] (Fig. 2B, d) were used. These gB molecules were expected not to be translocated into the rough endoplasmic reticulum (pRC/CMVSigDelgB) or to result in a soluble form of gB [pRC/CMVgB(MhdII)], which would be most likely incompatible with successful phenotypic complementation. Indeed, only single green fluorescent cells were recognized in these transfections (Fig. 2B, c and d), indicating the incompetence of these gB molecules for complementation. In addition, examination for the presence of released virus in supernatants of these transfected cultures by transfer to fresh HFF remained negative in this case (Table 2).

A number of expression plasmids encoding various gB mutants (Fig. 2B, e to j), several of which have been used before for stable constitutive expression in permissive cells and for characterization of biochemical and biological properties of the gB molecule (5, 31, 34, 35) were then tested for their potential to complement the gB-null genome. Of the expression plasmids encoding gBs with deletions in the cytoplasmic tail (Fig. 2B, e to g), only pRC/CMVgB(Del2) and pRC/CMVgB(Del3) supported formation of green fluorescent miniplaques (Fig. 2B, f and g), suggesting that the respective domains were not essential for viral replication. Deletion of amino acids 773 to 810 [pRC/CMVgB(Del1)] prevented the formation of miniplaques (Fig. 2B, e), suggesting that there might be an essential domain within this portion of the gB cytoplasmic tail.

In plasmid pRC/CMVgB(MhdI), hydrophobic domain 1 (MhdI) of gB is deleted (Fig. 2, h), a region that was discussed to play a role in cell-cell fusion (5). This mutant gB was not competent to induce the formation of miniplaques either (Fig. 2B, h). Cotransfections with pRC/CMVgB(ΔFur), encoding uncleavable gB protein due to a mutation of the furin recognition site (see Materials and Methods), or pRC/CMVgB(sINM), coding for gB in which the localization signal for the inner nuclear membrane (LSINM) is destroyed by a four-amino-acid substitution (38), clearly led to formation of miniplaques (Fig. 2B, i and j). This observation suggested that endoproteolytic processing by furin as well as the signal for the localization of gB to the inner nuclear membrane are possibly dispensable for virus replication in cell culture.

Expression of the gB proteins in the green fluorescent miniplaques.

In order to validate the significance of the transfection assay, the presence of gB within the miniplaques was examined after cotransfection with those gB expression plasmids that were of interest. For this purpose, immunofluorescence with a gB-specific antibody was performed after cotransfections with BACΔgB and expression plasmids encoding wild-type gB (pRC/CMVgB) or gBΔFur (pCR/CMVgBΔFur). The plasmid encoding gB without a signal peptide (pRC/CMVSigDelgB) was used as a negative control. To examine if gB is also present in cells that never developed miniplaques after cotransfection, the construct encoding a gB with a deletion of hydrophobic domain one [pRC/CMVgB(Mhd1)] was cotransfected.

As expected, cotransfections of BACΔgB with wild-type pRC/CMVgB and pRC/CMVgBΔFur again resulted in the formation of miniplaques that displayed a green fluorescence due to the expression of EGFP (Fig. 3, pRC/CMVgB and pRC/CMVgBΔFur, left panel). In both cases, a cell near the periphery of the plaque exhibited clear gB expression (Fig. 3, pRC/CMVgB and pRC/CMVgBΔFur, right panel). No gB-specific antigen was detectable in cells cotransfected with BACΔgB and pRC/CMVSigDelgB (Fig. 3, pRC/CMVSigDelgB, right panel).

In preliminary experiments, solitary expression of this plasmid was found to result in transient appearance in the cytoplasm of transfected cells of reduced amounts of gB protein. This may indicate the relative instability of this mutant gB product as a possible cause for the failure to detect its presence under the conditions of cotransfection. The single green fluorescent cells observed after cotransfection with pRC/CMVgB(Mhd1) however, again showed specific gB expression [Fig. 3, pRC/CMVgB(Mhd1), right panel]. These findings showed that gB is exclusively expressed in the cotransfected cells, i.e., in the case of plaque formation, a single cell only within a miniplaque expressed gB.

Construction of HCMV BAC genomes encoding mutant gB.

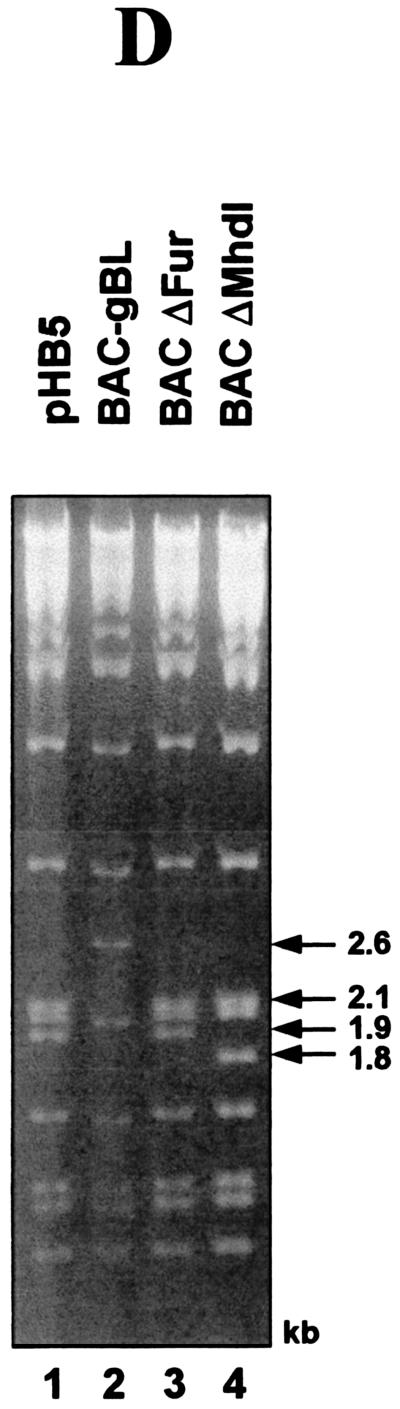

According to the results of the cotransfection assay, an HCMV BAC mutant with a destroyed furin cleavage site of gB should be viable, whereas a mutant with a deletion of the gB hydrophobic domain 1 should not be. To verify this notion in the viral context, two BAC mutants were generated. In a first step, BAC-gBL, which served as a platform for insertion of the gB genes with a deletion of either the furin recognition site or MhdI, was constructed (Fig. 4A). In this BAC, the fragment of the gB gene encoding the domain (amino acids 411 to 906) containing the furin cleavage motif as well as MhdI was deleted as described in Materials and Methods. The deletion removed a BglII site, and two BglII fragments of 2.1 kb and 1.9 kb of pHB5 (Fig. 4A) were replaced by a new 2.6-kb BglII fragment in the restriction pattern of BAC-gBL (Fig. 4D, compare lanes 1 and 2).

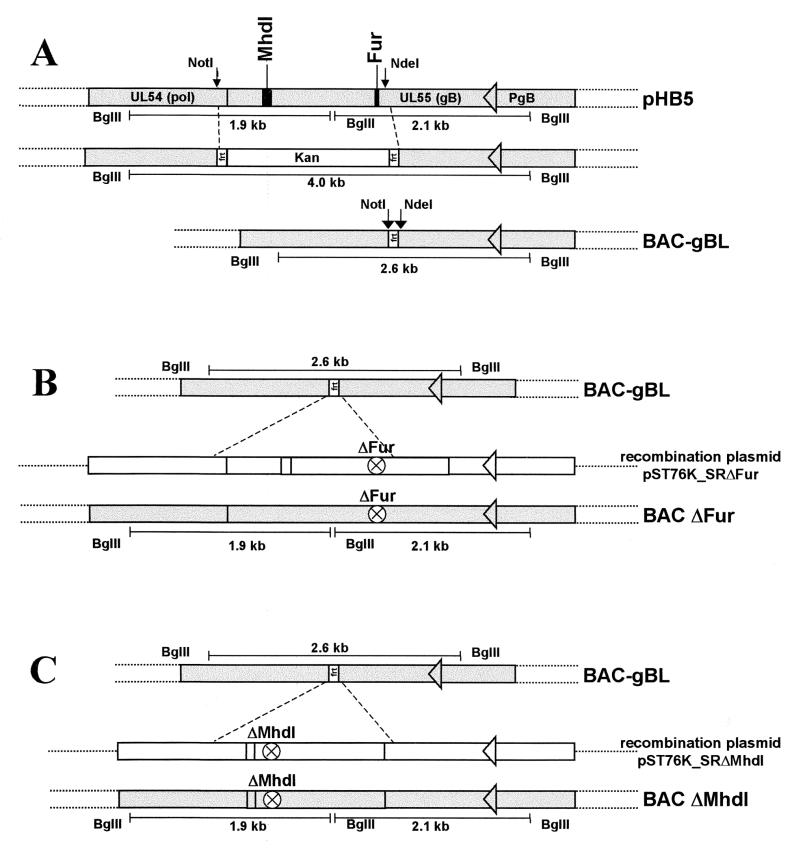

FIG. 4.

Construction and structural analysis of the BAC plasmid BAC-gBL and of the two mutant derivatives BACΔFur and BACΔMhdI. (A) Construction of BAC plasmid BAC-gBL. The top line depicts the fragment of BAC plasmid pHB5 containing gB ORF UL55 and its flanking regions, including the gB promoter (PgB) and part of adjacent ORF UL54. The relative positions of the furin cleavage site (Fur) and of MhdI are marked by black bars. A kanamycin resistance gene (Kan) flanked by two FRT sites was used to replace the fragment between the NotI and NdeI sites by ET recombination as described in Materials and Methods. The Kan gene was subsequently excised by Flp-mediated recombination, resulting in generation of BAC-gBL. (B and C) Modified DNA fragments carrying a deletion of either the furin cleavage site (ΔFur) (B) or MhdI (ΔMhdI) (C) were reinserted into BAC-gBL as described in Materials and Methods to generate BACΔFur and BACΔMhdI, respectively. The deletions are marked by circles. The sizes of the BglII fragments used for characterization are indicated underneath each BAC plasmid. (D) DNA of the BAC plasmids was digested with BglII, separated on a 0.8% agarose gel, and stained with ethidium bromide. The sizes of the characteristic BglII fragments of 2.6 kb (lane BACgBL), 2.1 and 1.9 kb (lanes pHB5 and BACΔFur), and 2.1 and 1.8 kb (lane BACΔMhdI) are indicated.

For the construction of BACΔMhdI and BACΔFur, the mutations were introduced into the BAC-gBL genome by a two-step mutagenesis procedure as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 4B and C). The resulting mutant clones were analyzed by BglII digestion and compared to the parental BAC plasmid BAC-gBL. The reinsertion of the mutant fragments reintroduces the BglII cleavage site. Accordingly, the 2.6-kb BglII fragment of BAC-gBL is missing in the restriction pattern of BACΔFur and BACΔMhdI (Fig. 4B, 4C, and 4D, lanes 3 and 4).

For the BACΔFur mutant, the expected 2.1-kb and 1.9-kb fragments reappeared, as shown by agarose gel electrophoreis (Fig. 4D, compare lanes 1, 2, and 3). A similar restriction pattern was observed for BACΔMhdI, but the 1.9-kb band was shifted to 1.8 kb as a result of the deletion of the coding sequence for Mhdl (Fig. 4D, lanes 1, 2, and 4; compare Fig. 4A and 4C). The relevant mutated regions were amplified by PCR and sequenced for additional confirmation of the introduced mutations. Restriction analysis and sequencing showed that the intended mutations were indeed introduced in the respective BAC plasmids.

Reconstitution of replication-competent virus from BAC plasmids.

To examine replication competence, BACΔMhdI and BACΔFur were transfected into MRC-5 cells. Approximately 1 week after transfection, BACΔFur induced formation of a spreading cytopathic effect. Supernatants of the transfected cells were used for infection of fresh fibroblasts and production of HCMVΔFur virus stocks.

In the case of transfection assays with BACΔMhdI, no cytopathic effect developed. To prove that the introduced mutation was responsible for the lethal phenotype, BACΔMhdI and cosmid pCM1029 (22), which carries the sequence of the HCMV genome spanning the deletion, were cotransfected. By cotransfection of cosmid pCM1029, rescue of BACΔMhdI was achieved, and a replication-competent viral revertant was obtained (data not shown), most likely as a result of repair of the mutation by homologous recombination.

These results corresponded with the predictions of the results obtained in the cotransfection studies that gB cleavage is dispensable for viral replication, whereas deletion of MhdI is lethal under the conditions used.

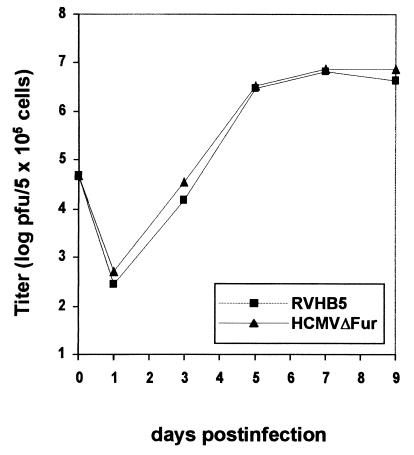

Analysis of replication-competent HCMVΔFur.

For further characterization of the replication-competent HCMVΔFur, multiple-step growth kinetics were performed as described in Materials and Methods. No differences in growth behavior of HCMVΔFur were observed compared to parental virus RVHB5 (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Multiple-step growth curves of HCMVΔFur and parental virus RVHB5. HFF were seeded into six-well dishes at a density of 5 × 105 cells/well and infected at an MOI of 0.1. At the indicated time points, the titer of infectious virus released into the supernatants of three independent infected cultures was determined by plaque assay.

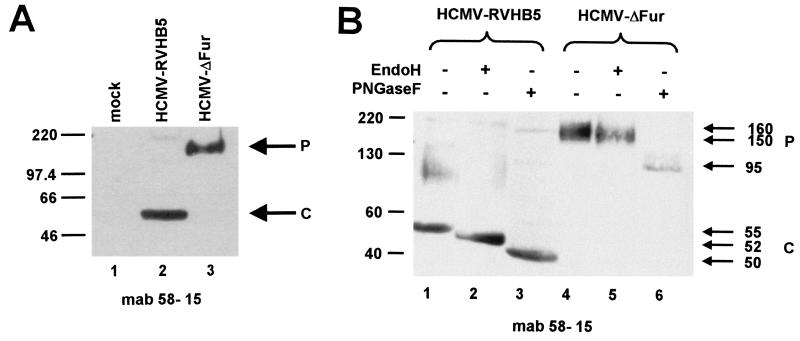

To confirm that gB in HCMVΔFur remains uncleaved, infected cells were examined by Western blot analysis. HCMVΔFur- and RVHB5-infected cells were harvested at 72 h after infection and separated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotting was carried out with monoclonal antibody 58-15 (10), recognizing a carboxy-terminal epitope of gB. In RVHB5-infected cells, the efficiently cleaved gB was observed, whereas in HCMVΔFur-infected cells, only the uncleaved precursor was recognized (Fig. 6A, lanes 2 and 3).

FIG. 6.

Analysis of gB proteins of infected cells and of cell-free virus. (A) Extracts of HFF infected with RVHB5 or HCMVΔFur and of noninfected cells (mock) were separated by SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred onto nitrocellulose, followed by incubation with monoclonal antibody (mab) 58-15. The positions of the uncleaved 150-kDa precursor (P) of gB and the carboxyl-terminal 58-kDa cleavage product (C) are marked by arrows. The positions of the marker proteins are indicated on the left. (B) Cell-free virus preparations of HCMV-RVHB5 and HCMVΔFur were concentrated by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 2 h and resuspended in lysis buffer prior to digestion with EndoH or PNGase F, separation by SDS-PAGE, electrotransfer onto nitrocellulose, and staining with monoclonal antibody 58-15. Treatment of the preparations with the endoglycosidases is indicated by +. The positions of the undigested and endoglycosidase-digested forms of the uncleaved precursor (P) of gB and those of the carboxyl-terminal cleavage product (C) are marked by arrows. The positions of the marker proteins are shown on the left (in kilodaltons).

Extracellular virus released from HCMVΔFur- and RVHB5-infected cells was further subjected to endoglycosidase treatment prior to analysis by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with monoclonal antibody 58-15. In contrast to wild-type gB of RVHB5, gB of HCMVΔFur was exclusively uncleaved (Fig. 6B, lanes 1 and 4). However, like wild-type gB, uncleaved HCMVΔFur gB was partially EndoH resistant as well as PNGase F sensitive, indicating that correct transport along the exocytic pathway through the Golgi apparatus had occurred (Fig. 6B, lanes 2, 3, 5, and 6).

We conclude from these data that endoproteolytic cleavage of gB is not essential for HCMV replication in cell culture.

DISCUSSION

The establishment of the BAC technology for HCMV (7) has greatly facilitated the introduction of any kind of mutation into the viral genome and the rescue of mutants with even strongly attenuated phenotypes. However, complementation of lethal phenotypes, e.g., as a consequence of deletion of a structural component such as the envelope glycoprotein gB, which is essential for viral replication in culture (28), has remained a major experimental obstacle. Due to the strict species and cell type specificity, efficient viral replication can be achieved only in human fibroblasts. Replication is also possible in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (27) and human retina cells (49), although to a lesser extent. All of these cell types exhibit properties, however, that limit their use for the establishment of stably transformed cell clones.

Nevertheless, generation of complementing cells has been achieved by retroviral transduction of primary cells (18, 25, 39, 41). Our attempts to phenotypically rescue an HCMV gB-null mutant in human fibroblast cell populations that were transduced with a retrovirus vector to achieve stable and homogenous expression of HCMV gB failed, however, for reasons that are presently unclear (Strive and Radsak, unpublished observations). Life-extended human fibroblast cell lines seem to be the best candidates for the production of a complementing system (17, 25, 34, 39). It remains to be shown if this cell system may be exploited for complementation of viral glycoproteins, since constitutive overexpression differs from regulated expression in the viral context and may result in transport errors and mislocalization of the recombinant products. Furthermore, constitutive expression of gB and other glycoproteins known to be fusogenic can cause problems, for fusogenic activity might eliminate the cell clones or populations expressing the highest amounts of gB by syncytium formation. One might speculate that in the surviving cell clones selected, the amount of gB protein is insufficient for complementation. Systems with inducible high-level gB expression have not been reported yet and remain to be tested for rescue of a gB-null mutant.

As an alternative to complementation in cell lines constitutively expressing gB molecules, we employed a transient-cotransfection assay to test whether gB mutants were competent for phenotypic complementation of a replication-deficient gB-null mutant. Although we usually obtained a small and variable number of miniplaques only after cotransfection of expression plasmids encoding wild-type gB or gB with a nonessential mutation, the results were highly reproducible. Expression plasmids encoding gB forms that were expected to be incompetent for phenotypic complementation, i.e., pRC/CMVSigDelgB and pRC/CMVgB(MhdII), never led to the formation of miniplaques.

One may argue that gB constructs which failed to complement the gB-null mutant did not express sufficient amounts of gB molecules. We consider this very unlikely for the following reasons. The amount of gB expressed in single cells after transfection probably depends on the number of plasmid copies taken up and is almost certainly different between the transfected cells. We think that this results in the release of a different amount of infectious progeny virions and differing sizes of the miniplaques rather than a failure in plaque formation. Different sizes of miniplaques were indeed observed. Furthermore, we could show by immunofluorescence that gB molecules are expressed in single cells after cotransfection of constructs that never led to miniplaque formation. After cotransfections that resulted in complementation, gB expression was restricted to one cell of the miniplaque only, supporting our view that gB proteins with nonessential mutations lead to one cycle of phenotypic complementation with release of viral progeny that is competent to abortively infect surrounding cells.

Viral particles released into the supernatant were found to be infectious upon transfer to fresh cultures but replication deficient. As expected, the amount of released viral particles was small. It has to be taken into account in this context that the numbers of infectious units observed in the supernatants represent minimum values because a portion of the released complemented virions may be readily readsorbed from the supernatant to noninfected cells of the transfected culture. This may also explain the relative variability of the number of infectious units obtained per milliliter of supernatant from different experiments. The short period of time when viral particles are present in the supernatant prior to readsorbance contributes to the fact that this experimental approach is certainly inadequate for isolation of phenotypically complemented virus.

Genetic rescue as a result of the cotransfections described could be excluded by the appropriate controls.

This assay can thus be used for rapid screening of HCMV gB structural domains that might be essential or nonessential for viral replication in permissive cell cultures. The assay cannot predict whether there is a quantitative impairment of a gB mutant. Thus, once a domain of gB was found to be nonessential for virus growth, the result has to be verified by construction of a corresponding viral mutant.

Mutations in the HCMV gB gene that did not support plaque formation under the conditions used concerned the coding sequences for the signal peptide, the membrane anchor domain, Mhd1, and a carboxyl-terminal domain of the molecule between amino acids 773 and 810. In the case of the hydrophobic domains, this result was expected, for the functional relevance of this portion of the molecule has been described (5, 43). Dispensable for viral growth in culture were the furin cleavage site in the luminal domain and defined deletions in the cytoplasmic tail of the gB molecule.

Regarding previous reports on functional domains of the gB molecule, the observation was intriguing that deletion of the carboxyl-terminal 50 amino acids of HCMV gB were apparently compatible with production of viable viral progeny. It has been reported that phosphorylation at Ser900 within this region is important for the retrieval of the molecule from the cell surface (21). Furthermore, it has been shown that this HCMV gB domain harbors a hexameric signal for targeting of the solitary gB molecule to the inner nuclear membrane, indicating that gB may be involved in budding at the inner nuclear membrane (38). To elucidate this obvious discrepancy to the observations in this study, the appropriate viral mutants have to be generated by means of the BAC technique described and subcellular translocation of the mutant gB proteins has to be examined in the context of mutant-virus-infected cells.

The results regarding the potential internal fusion domain and the furin cleavage motif were verified by construction of HCMV BAC mutants, BACΔMhdI as an example of a putative essential and BACΔFur as an example of a likely nonessential mutation in the gB protein. Both mutants exhibited the expected phenotype after transfection of the BAC constructs into permissive human fibroblasts and led only in the case of BACΔFur to a replication-competent virus. The gB protein in this mutant was correctly transported along the exocytic pathway, and the absence of its proteolytic cleavage by furin was compatible with unimpaired viral growth.

This was not unexpected for two reasons. (i) In some herpesvirus species, cleavable and uncleavable gB homologues appear to be functionally equivalent. Previous reports demonstrated that, e.g., replacement of cleavable gB protein of PRV by an uncleavable homologue of BHV-1 (30) remained without effect on viral viability. (ii) During the herpesvirus infectious cycle, gB homologues are translocated in an uncleaved form (independently of the presence of a furin cleavage motif) to the inner nuclear membrane (20), where they are thought to participate in budding of enveloped particles into the nuclear cisterna (24). It is feasible to assume that functional, i.e., fusogenic, envelope glycoproteins are involved in consecutive exit from the cisterna by fusion of the viral envelope with the outer nuclear membrane. These observations also support the view that furin cleavage of herpesvirus gB homologues with the respective motif is not a process needed for functional activation of an endogenous fusion potential, as in the case of influenza virus hemagglutinin (29) or HIV gp160.

Regarding that herpesvirus gB cleavability, if present, has been conserved during evolution of the herpesvirus species, it may be of relevance for viral survival in environments other than the artificial cell culture systems. It remains to be shown if uncleaved gB protein results in altered receptor binding properties in different cell types. It is conceivable that distribution of proteases in different host cells and organs plays a role in determination of tissue tropism and pathogenicity of herpesvirus infections. Recently an interesting additional function of the HCMV gB homologue has been reported; its binding to an as yet unidentified cellular receptor appears to induce the signal cascade of the interferon-responsive pathway in primary human fibroblasts (9, 46). It may be of interest to evaluate the biological competence of the gB cleavage-deficient mutant in this context.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Sonderforschungsbereich 286, Marburg, Teilprojekt A3) and by the Bundesministerium für Bildung and Forschung (BMBF), project 01GE9918. T.S. is a recipient of a Ph.D. scholarship of the Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes.

We are indebted to William Britt (Birmingham, Ala.) for providing monoclonal antibodies 58-15 and 27-156 and to Dorothee Gicklhorn and Beate Sodeik for helpful discussions during preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler, H., M. Messerle, M. Wagner, and U. H. Koszinowski. 2000. Cloning and mutagenesis of the murine gammaherpesvirus 68 genome as an infectious bacterial artificial chromosome. J. Virol. 74:6964–6974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldick, C. J., Jr., A. Marchini, C. E. Patterson, and T. Shenk. 1997. Human cytomegalovirus tegument protein pp71 (ppUL82) enhances the infectivity of viral DNA and accelerates the infectious cycle. J. Virol. 71:4400–4408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanton, R. A., and M. J. Tevethia. 1981. Immunoprecipitation of virus-specific immediate-early and early polypeptides from cells lytically infected with human cytomegalovirus strain AD 169. Virology 112:262–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bogner, E., K. Radsak, and M. F. Stinski. 1998. The gene product of human cytomegalovirus open reading frame UL56 binds the pac motif and has specific nuclease activity. J. Virol. 72:2259–2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bold, S., M. Ohlin, W. Garten, and K. Radsak. 1996. Structural domains involved in human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B-mediated cell-cell fusion. J. Gen. Virol. 77:2297–2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borst, E., and M. Messerle. 2000. Development of a cytomegalovirus vector for somatic gene therapy. Bone Marrow Transplant. 25:S80–S82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borst, E. M., G. Hahn, U. H. Koszinowski, and M. Messerle. 1999. Cloning of the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) genome as an infectious bacterial artificial chromosome in Escherichia coli: a new approach for construction of HCMV mutants. J. Virol. 73:8320–8329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borst, E. M., S. Mathys, M. Wagner, W. Muranyi, and M. Messerle. 2001. Genetic evidence of an essential role for cytomegalovirus small capsid protein in viral growth. J. Virol. 75:1450–1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyle, K. A., R. L. Pietropaolo, and T. Compton. 1999. Engagement of the cellular receptor for glycoprotein B of human cytomegalovirus activates the interferon-responsive pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:3607–3613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Britt, W. J., and L. G. Vugler. 1992. Oligomerization of the human cytomegalovirus major envelope glycoprotein complex gB (gp55–116). J. Virol. 66:6747–6754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Britt, W. J., and L. G. Vugler. 1989. Processing of the gp55–116 envelope glycoprotein complex (gB) of human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 63:403–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Britt, W. S., and C. A. Alford. 1996. Cytomegalovirus, p.2493–2523. In B. Fields et al. (ed.), Fields virology, 3rd ed. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 13.Chang, A. C., and S. N. Cohen. 1978. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15.A cryptic miniplasmid. J. Bacteriol. 134:1141–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chee, M. S., A. T. Bankier, S. Beck, R. Bohni, C. M. Brown, R. Cerny, T. Horsnell, C. A. Hutchison III, T. Kouzarides, J. A. Martignetti, et al. 1990. Analysis of the protein-coding content of the sequence of human cytomegalovirus strain AD169. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 154:125–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cherepanov, P. P., and W. Wackernagel. 1995. Gene disruption in Escherichia coli: TcR and KmR cassettes with the option of Flp-catalyzed excision of the antibiotic-resistance determinant. Gene 158:9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Claesson-Welsh, L., and P. G. Spear. 1986. Oligomerization of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein B. J. Virol. 60:803–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Compton, T. 1993. An immortalized human fibroblast cell line is permissive for human cytomegalovirus infection. J. Virol. 67:3644–3648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Courcelle, C. T., J. Courcelle, M. N. Prichard, and E. S. Mocarski. 2001. Requirement for uracil-DNA glycosylase during the transition to late-phase cytomegalovirus DNA replication. J. Virol. 75:7592–7601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eberle, R., and R. J. Courtney. 1982. Multimeric forms of herpes simplex virus type 2 glycoproteins. J. Virol. 41:348–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eggers, M., E. Bogner, B. Agricola, H. F. Kern, and K. Radsak. 1992. Inhibition of human cytomegalovirus maturation by brefeldin A. J. Gen. Virol. 73:2679–2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fish, K. N., C. Soderberg-Naucler, and J. A. Nelson. 1998. Steady-state plasma membrane expression of human cytomegalovirus gB is determined by the phosphorylation state of Ser900. J. Virol. 72:6657–6664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleckenstein, B., I. Muller, and J. Collins. 1982. Cloning of the complete human cytomegalovirus genome in cosmids. Gene 18:39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gong, M., T. Ooka, T. Matsuo, and E. Kieff. 1987. Epstein-Barr virus glycoprotein homologous to herpes simplex virus gB. J. Virol. 61:499–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Granzow, H., B. G. Klupp, W. Fuchs, J. Veits, N. Osterrieder, and T. C. Mettenleiter. 2001. Egress of alphaherpesviruses: comparative ultrastructural study. J. Virol. 75:3675–3684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greaves, R. F., and E. S. Mocarski. 1998. Defective growth correlates with reduced accumulation of a viral DNA replication protein after low-multiplicity infection by a human cytomegalovirus ie1 mutant. J. Virol. 72:366–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hampl, H., T. Ben-Porat, L. Ehrlicher, K. O. Habermehl, and A. S. Kaplan. 1984. Characterization of the envelope proteins of pseudorabies virus. J. Virol. 52:583–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ho, D. D., T. R. Rota, C. A. Andrews, and M. S. Hirsch. 1984. Replication of human cytomegalovirus in endothelial cells. J. Infect. Dis. 150:956–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hobom, U., W. Brune, M. Messerle, G. Hahn, and U. H. Koszinowski. 2000. Fast screening procedures for random transposon libraries of cloned herpesvirus genomes: mutational analysis of human cytomegalovirus envelope glycoprotein genes. J. Virol. 74:7720–7729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klenk, H. D., and R. Rott. 1988. The molecular biology of influenza virus pathogenicity. Adv. Virus Res. 34:247–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kopp, A., E. Blewett, V. Misra, and T. C. Mettenleiter. 1994. Proteolytic cleavage of bovine herpesvirus 1 (BHV-1) glycoprotein gB is not necessary for its function in BHV-1 or pseudorabies virus. J. Virol. 68:1667–1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee, S. K., T. Compton, and R. Longnecker. 1997. Failure to complement infectivity of EBV and HSV-1 glycoprotein B (gB) deletion mutants with gBs from different human herpesvirus subfamilies. Virology 237:170–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loh, L. C. 1991. Synthesis and processing of the major envelope glycoprotein of murine cytomegalovirus. Virology 180:239–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCune, J. M., L. B. Rabin, M. B. Feinberg, M. Lieberman, J. C. Kosek, G. R. Reyes, and I. L. Weissman. 1988. Endoproteolytic cleavage of gp160 is required for the activation of human immunodeficiency virus. Cell 53:55–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McSharry, B. P., C. J. Jones, J. W. Skinner, D. Kipling, and G. W. Wilkinson. 2001. Human telomerase reverse transcriptase-immortalized MRC-5 and HCA2 human fibroblasts are fully permissive for human cytomegalovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 82:855–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meredith, D. M., J. M. Stocks, G. R. Whittaker, I. W. Halliburton, B. W. Snowden, and R. A. Killington. 1989. Identification of the gB homologues of equine herpesvirus types 1 and 4 as disulphide-linked heterodimers and their characterization using monoclonal antibodies. J. Gen. Virol. 70:1161–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Messerle, M., I. Crnkovic, W. Hammerschmidt, H. Ziegler, and U. H. Koszinowski. 1997. Cloning and mutagenesis of a herpesvirus genome as an infectious bacterial artificial chromosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:14759–14763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mettenleiter, T. C., and P. G. Spear. 1994. Glycoprotein gB (gII) of pseudorabies virus can functionally substitute for glycoprotein gB in herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 68:500–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meyer, G. A., and K. D. Radsak. 2000. Identification of a novel signal sequence that targets transmembrane proteins to the nuclear envelope inner membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 275:3857–3866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mocarski, E. S., Jr., and G. W. Kemble. 1996. Recombinant cytomegaloviruses for study of replication and pathogenesis. Intervirology 39:320–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Posfai, G., M. D. Koob, H. A. Kirkpatrick, and F. R. Blattner. 1997. Versatile insertion plasmids for targeted genome manipulations in bacteria: isolation, deletion, and rescue of the pathogenicity island LEE of the Escherichia coli O157:H7 genome. J. Bacteriol. 179:4426–4428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prichard, M. N., N. Gao, S. Jairath, G. Mulamba, P. Krosky, D. M. Coen, B. O. Parker, and G. S. Pari. 1999. A recombinant human cytomegalovirus with a large deletion in UL97 has a severe replication deficiency. J. Virol. 73:5663–5670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reis, B., E. Bogner, M. Reschke, A. Richter, T. Mockenhaupt, and K. Radsak. 1993. Stable constitutive expression of glycoprotein B (gpUL55) of human cytomegalovirus in permissive astrocytoma cells. J. Gen. Virol. 74:1371–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reschke, M., B. Reis, K. Noding, D. Rohsiepe, A. Richter, T. Mockenhaupt, W. Garten, and K. Radsak. 1995. Constitutive expression of human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B (gpUL55) with mutagenized carboxy-terminal hydrophobic domains. J. Gen. Virol. 76:113–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ross, L. J., M. Sanderson, S. D. Scott, M. M. Binns, T. Doel, and B. Milne. 1989. Nucleotide sequence and characterization of the Marek’s disease virus homologue of glycoprotein B of herpes simplex virus. J. Gen. Virol. 70:1789–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sambrook, J., E. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 46.Simmen, K. A., J. Singh, B. G. Luukkonen, M. Lopper, A. Bittner, N. E. Miller, M. R. Jackson, T. Compton, and K. Fruh. 2001. Global modulation of cellular transcription by human cytomegalovirus is initiated by viral glycoprotein B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:7140–7145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strive, T. 1997. Graduate thesis. Faculty of Biology, University of Marburg, Marburg, Germany.

- 48.Sullivan, D. C., G. P. Allen, and D. J. O’Callaghan. 1989. Synthesis and processing of equine herpesvirus type 1 glycoprotein 14. Virology 173:638–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tugizov, S., E. Maidji, and L. Pereira. 1996. Role of apical and basolateral membranes in replication of human cytomegalovirus in polarized retinal pigment epithelial cells. J. Gen. Virol. 77:61–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Drunen Littel-van den Hurk, S., and L. A. Babiuk. 1986. Synthesis and processing of bovine herpesvirus 1 glycoproteins. J. Virol. 59:401–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vey, M., W. Schafer, B. Reis, R. Ohuchi, W. Britt, W. Garten, H. D. Klenk, and K. Radsak. 1995. Proteolytic processing of human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B (gpUL55) is mediated by the human endoprotease furin. Virology 206:746–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weissenhorn, W., A. Dessen, S. C. Harrison, J. J. Skehel, and D. C. Wiley. 1997. Atomic structure of the ectodomain from HIV-1 gp41. Nature 387:426–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilson, D. W., N. Davis-Poynter, and A. C. Minson. 1994. Mutations in the cytoplasmic tail of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein H suppress cell fusion by a syncytial strain. J. Virol. 68:6985–6993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilson, I. A., J. J. Skehel, and D. C. Wiley. 1981. Structure of the haemagglutinin membrane glycoprotein of influenza virus at 3 A resolution. Nature 289:366–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]