Abstract

The immunodominant epitopes on the hemagglutinin protein of rinderpest virus (RPV-H) were determined by analyzing selected monoclonal antibody (MAb)-resistant mutants and estimating the level of antibody against each epitope in five RPV-infected rabbits with the competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (c-ELISA). Six neutralizing epitopes were identified, at residues 474 (epitope A), 243 (B), 548 to 551 (D), 587 to 592 (E), 310 to 313 (G), and 383 to 387 (H), from the data on the amino acid substitutions of hemagglutinin protein of MAb-resistant mutants and the reactivities of MAbs against RPV-H to the other morbilliviruses. The epitopes identified in this study are all positioned on the loop of the propeller-like structure in a hypothetical three-dimensional model of RPV-H (J. P. M. Langedijk et al., J. Virol. 71:6155-6167, 1997). Polyclonal sera obtained from five rabbits infected experimentally with RPV were examined by c-ELISA using a biotinylated MAb against each epitope as a competitor. Although these rabbit sera hardly blocked binding of each MAb to epitopes A and B, they moderately blocked binding of each MAb to epitopes G and D and strongly blocked binding of each MAb to epitopes E and H. These results suggest that epitopes at residues 383 to 387 and 587 to 592 may be immunodominant in humoral immunity to RPV infection.

Rinderpest virus (RPV) causes an acute, febrile, and highly contagious disease in cattle and wild bovines in Africa, the Middle East, the Near East, and south Asia. RPV belongs to the Morbillivirus genus of the family Paramyxoviridae and shares this group with measles virus (MV), canine distemper virus (CDV), phocine distemper virus, and peste-des-petits-ruminants virus. The morbilliviruses possess a single-stranded, negative RNA with the genome containing six genes, encoding the hemagglutinin (H) and fusion (F) surface glycoproteins, the nucleocapsid protein (NP), the envelope matrix protein, the polymerase or large protein, and the polymerase-associated protein.

The surface glycoproteins mediate virus attachment and penetration to host cells and play a vital role in induction of protective immunity. Although the F protein can be the target of neutralizing antibodies (13), most of the protective immunity to MV is directed against the H protein (4). Similarly, the neutralizing antibodies have been induced with much higher titers in cattle by immunization with vaccinia virus recombinant encoding the H protein of RPV (RPV-H) than with that encoding the F protein (21). The B-cell epitopes on the H protein of MV (MV-H) have been analyzed by several groups by using monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) and synthetic peptides. These studies have revealed that seven neutralizing antigenic sites are mapped on MV-H (3, 5, 7, 10-12, 22). However, the immunodominant neutralizing epitope on H protein remains unclear, while a major antigenic epitope, recognized by acute postinfection human sera, has been identified using synthetic peptides of MV-F protein (1). It is generally difficult to apply peptide scanning to identify the conformational epitopes because it has led to the identification of mainly linear epitopes. A previous study using competitive binding assays with MAbs has shown that the neutralizing epitopes on RPV-H are predominantly dependent on a conformational structure and that at least seven neutralizing antigenic sites are located on it (16).

In this study, we used a panel of neutralizing MAbs against RPV-H (16) to select a series of escape mutants. We determined the sequence of the H gene of each mutant to map the neutralizing epitopes of RPV-H. In the case of RPV, the rabbit, which shows symptoms similar to those seen in natural hosts when infected, provides an ideal small-animal model (8, 20). Finally, the immunogenicity of each epitope was assessed by the competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (c-ELISA) with MAbs in rabbits immunized with RPV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, virus, and MAbs.

Vero and NA cells, a mouse neuroblastoma cell line C-1300, were cultured in a growth medium consisting of Eagle's minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, tryptose phosphate broth, and antibiotics. NA cells were kindly supplied by F. A. McMorris, The Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, Pa. The lapinized (L) strain of RPV (8), at the 37th passage in Vero cells, was used for the production of MAb-resistant (MR) mutants. The L strain was propagated in NA cells to prepare the antigen for c-ELISA. Nineteen MAbs against the H protein of the L strain, which were established previously (16), were used for production of MR mutants.

Production of MR mutants.

Vero cells infected with a wild-type L strain were cultured in a 24-well plate in growth medium containing 10% mouse ascites fluid of each MAb and passaged until the monolayer showed a cytopathic effect caused by MR mutants. When about 80% of an RPV-infected Vero cell monolayer showed cytopathic change, the culture supernatant was collected. The MR mutants in this culture supernatant were cloned by plaque formation as described previously (15). The reactivities of these clones to 19 MAbs against RPV-H were investigated by immunofluorescent antibody (IFA) tests as described previously (15).

Sequence determination of H genes from wild-type and MR RPV mutants.

To sequence H genes of wild-type and MR mutants, total RNA was prepared from Vero cells infected with each mutant with Isogen (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan) according to the instructions of the supplier. cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using Ready-To-Go You-Prime First-Strand beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) and the primer URP1 (5"-CGACGTTGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTAGGATGCAAGATCATCCACC-3"), which has an additional M13 universal sequence for sequencing (underlined). Three overlapped fragments covering the whole RPV-H gene were amplified by PCR on the cDNA template using the following three sets of primers: upstream URP1 and downstream RRP1, 5"-TTTCACACAGGAAACAGCTATGACCTGAAATATTGTAGCCACGACC-3", which has an additional M13 reversal sequence for sequencing (double underlined); upstream URP2, 5"-CGACGTTGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTAAGGTCAATTCTCTAACATGTC-3", and downstream RRP2, 5"-TTTCACACAGGAAACAGCTATGACCGAGGAATAGTCAGCCAGTAC-3"; and upstream URP3, 5"-CGACGTTGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTACTCAGGGATGGACTTATACA-3", and downstream RRP3, 5"-TTTCACACAGGAAACAGCTATGACCTGCAGCGCGGTGCCTGG-3". After the primers had been removed from PCR products by ultrafiltration (Suprec-02; Takara, Shiga, Japan), the nucleotide sequence of the resulting cDNA was determined by the thermal cycle sequencing method with an AutoCycle Sequencing kit and an ALFred DNA sequencer (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Four Cy5-labeled primers, 5"-GCTCGGTGGAGTCTGATACC-3", 5"-TAACTGGTGCATCAGTCCCC-3", 5"-CCACTCTTTCAGCAGTAGATCC-3", and 5"-TGATGGGGAGAGTAAGGATGTTAGG-3", were also used to confirm the ambiguous sequences of RPV-H genes. Sequences were analyzed using Genetyx software for the Macintosh, version 6.0.1.

Immunization of RPV in rabbits and sampling.

Five male New Zealand White rabbits (Japan SLC, Shizuoka, Japan) with an average body weight of 2.0 kg were intravenously inoculated with a 50% tissue culture infective dose of 104 of the L strain at the 39th passage in Vero cells. Sera were collected intravenously from rabbits 4 weeks after inoculation. The serum samples were stored at −20°C until use.

c-ELISA.

c-ELISA was performed essentially as described previously (18). Briefly, the RPV-infected NA cell lysate with a lysis buffer containing 20 mM 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS)(Dojin-kagaku, Kumamoto, Japan) was clarified by centrifugation. The crude extract was used as an antigen for c-ELISA. The MAbs were purified and biotinylated as described previously (16). Each well of a 96-well microtiter plate was coated with the antigen at 4°C overnight and treated with 5% skimmed milk at 37°C for 1 h to block the nonspecific reaction. A series of twofold dilutions of rabbit sera was put in the antigen-coated wells and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. After being washed five times with phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20, the assay was followed by appropriate dilutions of biotinylated anti-H MAbs 50 (to epitope group A), 30 (to B), 59 (to D), 47 (to E), 31 (to G), and E-1 (to H) using a VECTASTAIN Elite ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.). After the reaction mixture had been visualized with o-phenylenediamine and the reaction was stopped with H2SO4, the resulting optical density at 490 nm was measured with an ELISA reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). The serum titer was defined as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution that reduced the specific absorbency by more than 50%.

RESULTS

Reactivities of MAbs to MR mutants.

Fifteen MR mutants showed cytopathic change on the 3rd to 24th passages of RPV-infected Vero cells under the pressure of each MAb. However, even after 37 passages, no cytopathic effects of RPV-infected Vero cells were observed in culture media containing MAbs S-1 (to antigenic site II), 20 (to IV), B-1 (to V), or 80 (to VII). After these mutants had been cloned by the plaque purification method, the antigenic and genetic properties of the clones were analyzed.

The pattern of reactivity of MR mutants to MAbs in the IFA test indicates that there are eight individual epitopes (A to H) on RPV-H (Table 1). These epitopes are basically in accordance with those (antigenic sites I to VII) determined by the competitive binding assay described previously (16). Although MAbs S-1 (to antigenic site II) and 20 (to IV) reacted to all of these mutants, MAbs B-1 and 80 did not react to the MAb 41-resistant mutant (MR 41) in the epitope F group and to four mutants in the epitope H group, respectively. The reactivity of MAbs was nonreciprocal between the mutant clones in the same epitope E and G groups.

TABLE 1.

Reactivities of anti-H MAbs to MR clones in IFA testsa

| MR mutant | Epitope [antigenic site(s)b] | Reactivity with MAb

|

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 30 | S-1 | 29 | 59 | 1d | 53 | 19 | 47 | 20 | 41 | B-1 | 71 | 31 | E-1 | 32 | 39 | 61 | 80 | ||

| 50 | A (I) | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 30 | B (II) | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 29 | C (III) | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 59 | D (III + IV) | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 1d | E (III + IV) | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 53 | E (IV) | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 19 | E (IV) | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 47 | E (IV) | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 41 | F (V) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 71 | G (VI) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 31 | G (VI) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| E-1 | H (VII) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 32 | H (VII) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 39 | H (VII) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 61 | H (VII) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

The IFA test was performed with a MAb dilution of 1:500 with methanol-fixed cells infected with each MR mutant. +, positive; −, negative

Antigenic sites were identified on the basis of competitive binding assays with MAbs (16).

Epitope mapping of RPV-H by sequencing H genes of MR mutants.

Direct sequencing of H genes of RPV mutants was performed using reverse transcription-PCR and the thermal cycle sequencing method for comparison of H genes in MR mutants and the wild-type L strain. The amino acid substitutions of MR mutants selected by MAbs are shown in Table 2. A single-point mutation responsible for each of the neutralizing epitopes was found in each of the mutants selected by using MAbs 50 (from Pro-474 to His [Pro-474-His]), 30 (Arg-243-Trp), 1d (Lys-592-Asn), 53 (Asp-587-Tyr), 19 (Gly-589-Glu), 41 (Lys-556-Glu), 31 (Gly-312-Arg), E-1 (Arg-387-Gln), 32 (Arg-387-Gln), and 61 (Arg-383-Gln). Double or triple substitutions were observed in MRs 29 (epitope C), 59 (epitope D), 47 (epitope E), 71 (epitope G), and 39 (epitope H).

TABLE 2.

Predicted coding changes in the H proteins of MR clones compared with the H protein of their progenitor, strain L

| MR clone | Epitope | Position | Amino acid change |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | A | 474 | Pro→His |

| 30 | B | 243 | Arg→Trp |

| 29 | C | 483 | Leu→Pro |

| 508 | Val→Ala | ||

| 59 | D | 342 | Val→Ala |

| 548 | Leu→Pro | ||

| 551 | Tyr→His | ||

| 1d | E | 592 | Lys→Asn |

| 53 | E | 587 | Asp→Tyr |

| 19 | E | 589 | Gly→Glu |

| 47 | E | 96 | Phe→Val |

| 589 | Gly→Glu | ||

| 41 | F | 556 | Lys→Glu |

| 71 | G | 310 | Tyr→His |

| 313 | Leu→Ser | ||

| 31 | G | 312 | Gly→Arg |

| E-1 | H | 387 | Arg→Gln |

| 32 | H | 387 | Arg→Gln |

| 39 | H | 96 | Phe→Val |

| 387 | Arg→Gln | ||

| 61 | H | 383 | Arg→Gln |

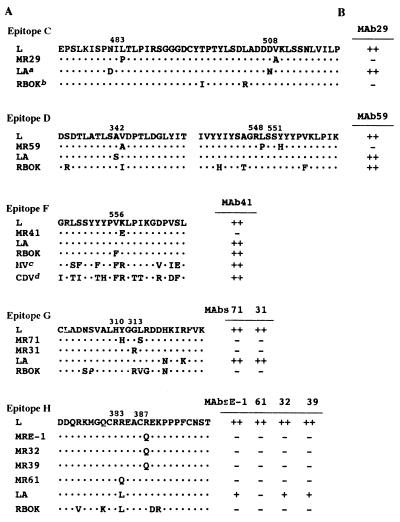

To determine whether those substitutions were effective for the destruction of each epitope, the deduced amino acid sequences on the positions associated with the substitutions were compared with those of other morbilliviruses (Fig. 1). Although the amino acids Leu-483 and Val-508 were conserved among L, LA, and RBOK strains, MAb 29, which led to the substitutions on these positions, failed to react with the RBOK strain. Therefore, the position of epitope C on RPV-H could not be identified.

FIG. 1.

Relationships of diversity of amino acid sequences among morbilliviruses to positions associated with amino acid changes in MR mutants and conservation of those epitopes. (A) Deduced amino acid sequence alignment of the wild-type L strain, MR mutants, and other morbilliviruses. Dots indicate positions of sequence identity with the wild-type L strain. Sequences for comparison with L strains were from the following sources (GenBank accession number): LA (D82982), RBOK (Z30699), MV, Edmonston strain (K01711), and CDV, Onderstepoort strain (D00758). (B) Reactivities of MAbs to those viruses in IFA tests (16). Results of IFA tests are shown as the following ascitic fluid dilution endpoints: ++, ≧1:1000; +, <1:1000 to ≧1:100; −, <1;100.

Three substitutions, Val-342-Ala, Leu-548-Pro, and Tyr-551-His, were shown in alignment with the wild-type L strain and MR 59 in the epitope D group. The sequence around amino acids (aa) 548 to 551 was well conserved among L, LA, and RBOK strains, while the sequence around aa 342 was not. Since MAb 59 was commonly reactive with RPV strains, epitope D was mapped on aa 548 to 551.

In the epitope G group, MR 71 showed the substitutions Tyr-310-His and Leu-313-Ser, while MR 31 showed the Gly-312-Arg substitution. The sequence around those substitutions was conserved between the L and LA strains, while it was varied between the L and RBOK strains. MAbs 71 and 31, used for selection of those MR mutants, reacted to the LA strain but not to the RBOK strain. The results of the alignment analysis are in accordance with those of reactivities of MAbs. Therefore, epitope G was identified on aa 310 to 313 of RPV-H.

The same substitution, Arg-387-Gln, appeared in MRs E-1, 32, and 39; a single substitution, Arg-383-Gln, appeared in MR 61. It has been shown that the reactive pattern of MAb 61 to the LA strain was different from that of the other MAbs to epitope H; namely, MAb 61 failed to react to the LA strain, but MAbs E-1, 32, and 39 reacted to it weakly. These results indicated that a single substitution in MR 61, Arg-383-Gln, caused a dramatic alteration of the epitope H structure, while the substitution Arg-383-Leu in the LA strain caused mild alteration. Since another substitution, Phe-96-Val, was observed only with MR 39 of these mutants, this substitution seemed to be ineffective for construction of epitope H. Epitope H was mapped on aa 383 to 387.

Epitopes A, B, and E were mapped at 474-Pro, 243-Arg, and residues 587 to 592, respectively, since the antigenic characterization of MR mutants and wild-type L, LA, and RBOK strains using MAbs against A, B, and E agrees with sequencing analysis of those strains around each substitution caused by those MAbs (data not shown).

A single amino acid change, Lys-556-Glu, was observed in the MR 41 clone. MAb 41 has been shown to react across a range of morbilliviruses (16), suggesting that the epitope against MAb 41 will be in a conserved region. However, the amino acid corresponding to this position (aa 556) was Arg, not Lys, in both MV and CDV strains. Moreover, this position was hydrophobic, while the other predicted epitope regions, A, B, D, E, G, and H, were hydrophilic (Fig. 2A). Based on this evidence, we assume that the region at aa 556 is not an epitope for MAb 41, although this position is important for the structure of epitope F.

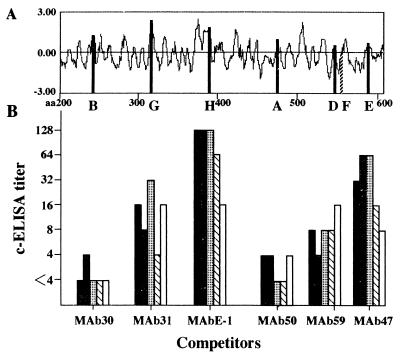

FIG. 2.

The predicted positions of neutralizing epitopes on the H protein of L strain by hydropathy plots (A) and comparison of c-ELISA titers in five rabbits infected with RPV (B). The relative hydropathic index was calculated by the method of Chou and Fasman (2). Sera collected from five rabbits 4 weeks after infection with RPV were tested by c-ELISA with biotinylated anti-H MAbs 50 (to epitope group A), 30 (to B), 59 (to D), 47 (to E), 31 (to G), or E-1 (to H) as competitors. The serum titer was defined as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution that reduced the specific absorbency by more than 50%. Columns indicate the titers of the individual rabbit samples. Results shown are representative of two experiments.

Identification of an immunodominant epitope(s) on RPV-H.

To determine the immunodominant epitope(s) on RPV-H, we estimated the antibody level against each epitope for five rabbits infected experimentally with RPV by c-ELISA (Fig. 2B). MAbs 50, 30, 59, 47, 31, and E-1 against epitope A, B, D, E, G, or H, respectively, mapped on RPV-H as described above and were purified and biotinylated to be used as competitors in c-ELISA. The quality of biotinylated MAbs was checked by measuring the c-ELISA antibody titer of mouse ascites fluid containing the same or anti-NP MAbs. The ascites containing the same MAbs as competitors used in c-ELISA had titers of over 5,120, while anti-NP MAb (Y13)-rich ascites fluid (16) had a titer of less than 4 by c-ELISA analysis with those biotinylated MAbs. When biotinylated MAb E-1 against the epitope H was used as a competitor in c-ELISA, the highest titer, 128, was detected in three of five rabbits infected with RPV. The remaining two rabbits also had high titers, 64 and 16, against epitope H. RPV-infected rabbits had a c-ELISA antibody against epitope E with comparatively high titers, 8 to 64, and had antibodies against epitopes D and G with moderate titers, 4 to 32. The lowest titers, below 4, were shown in those rabbits in c-ELISA with biotinylated MAbs 50 and 30 to epitopes A and B, respectively. The geometric mean values of c-ELISA titers using anti-G MAb 31, anti-H MAb E-1, anti-D MAb 59, and anti-E MAb 47 as competitors are 12.1, 73.5, 8.0, and 27.9, respectively. Moreover, MAbs E-1 and 59 have strong neutralizing activity (16). Taken together, these results suggest that epitopes H at aa 383 to 387 and E at aa 587 to 592 are immunodominant neutralizing epitopes.

DISCUSSION

Vaccinia virus recombinants expressing the H gene of RPV have been shown to induce virus-neutralizing antibodies and to completely protect against cattle and rabbit plague (19, 21). We demonstrated that anti-H MAbs against RPV are dominant in eliciting neutralizing activity (16). Knowledge of the localization of immunodominant epitopes and functional domains in RPV-H is important for evaluating a vaccine strain or designing a new type of vaccine such as a polyvalent recombinant.

MV was estimated to have a mutation rate of 9 × 10−5 per base per replication and a genomic mutation rate of 1.43 per replication (14). It has also been shown that MR mutants were present in the stock at a rate of approximately 1 per 3,000 PFU (14). Since the titer of the RPV stock used in this study was too low (104 PFU/ml) to obtain MR mutants from it, we attempted to select resistant mutants during the serial culture of RPV-infected cells under the pressure of each MAb. Finally, 15 kinds of MR mutants were established, and no mutants were generated by using four MAbs (B-1, 80, S-1, and 20). Although two MAbs, B-1 and 80, failed to react to these mutants in epitope F and H groups, respectively, the remaining MAbs, S-1 and 20, reacted to all MR mutants (Table 1). These results show that MAbs B-1 and 80 recognize epitopes F and H, respectively, and that MAbs S-1 and 20 recognize epitopes distinct from those that have been identified in this study.

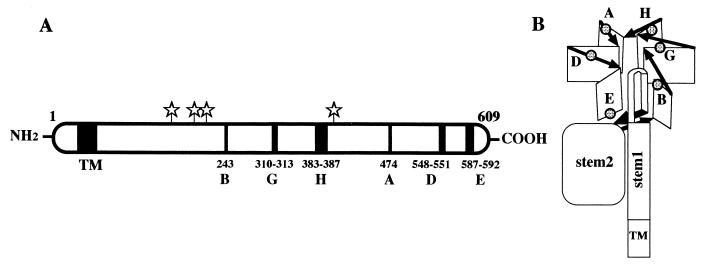

A three-dimensional (3D) structure model of morbillivirus H protein has been proposed on the basis of homology modeling using crystal structures of neuraminidases of influenza viruses A and B, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2, and Vibrio cholerae (9). The model is a superbarrel comprising six similarly folded antiparallel β-sheets of four strands each. In the superbarrel, the six sheets (β1 to -6) are arranged cyclically around an axis through the center of the molecule like the blades of a propeller (Fig. 3B). Loop structures, designated L01, L12, L23, and L34, exist between strands 4 and 1, 1 and 2, 2 and 3, and 3 and 4, respectively, on each β sheet. Loops L01 and L23 protrude from the top surface, and loops L12 and L34 are on the bottom surface. All of the six neutralizing epitopes identified in this study are positioned on the loop of each propeller-like structure. Our results reveal that epitopes B, G, H, A, and D are located on β1L23, β2L23, β3L23, β5L01, and β6L01 on the top surface of the propeller-like structure, respectively, while epitope E is located on β6L34 on the bottom surface. Hu et al. (6) demonstrated that carbohydrate side chains have a great effect on the antigenicity of MV-H. For RPV, three potential glycosylation sites are located on the postulated stem 2 region, and one potential glycosylation site is located on loop β3L23. Although epitope H is located near this glycosylation site on β3L23, there was no alteration in the potential glycosylation of any of the MR mutants in this study (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

Locations of the neutralizing epitopes of RPV-H in a schematic illustration (A) and in the 3D structure model proposed by Langedijk et al. (9) (B). Stars indicate the predicted N-linked glycosylation sites. The six sheets in the β-propeller structure are shown as rectangles. Stem and transmembrane (TM) regions and the direction of the polypeptide chain (arrows) are indicated.

We were unable to determine the epitope recognized by MAbs 41 and B-1, which reacted to all morbilliviruses, although we succeeded in establishing an escape mutant against MAb 41. The epitope against these MAbs was predicted to exist in a highly conserved region, because these MAbs showed the same affinities to MV and CDV as to homologous RPV (16). However, the single substitution at aa 556 of MR 41 is located in a variable region in morbilliviruses, a hydrophobic region and a β-sheet structure of β6, but not a loop. These results imply that the domain at aa 556 is not a genuine epitope and that this substitution influences the antigenicity of the epitope against these MAbs. In the alignment of amino acid sequences of HA protein, there is only one long identical amino acid sequence of 13-mer (aa 90 to 102) in all morbilliviruses. This region seems to be a candidate for the conserved epitope. The 3D model of HA protein of morbillivirus shows that this domain is sterically located near aa 556. If the domain at aa 90 to 102 is a genuine epitope for these MAbs, these results suggest that this substitution causes an alteration in the structure of the C-terminal region of RPV-H and the steric hindrance for an epitope against these MAbs.

The epitopes B on β1L23 and A on β5L01 may be minor antigenic sites for induction of the neutralizing antibody to RPV because few of the RPV-infected rabbits had antibodies against these epitopes (Fig. 2B). However, both antigenic sites of MV-H were determined by some investigators. Fournier et al. (3) demonstrated a linear neutralizing epitope, aa 244 to 250, on MV-H from the reactivity of MAbs to a synthetic peptide, while we identified the conformational epitope B at aa 243 next to this sequence on the same β1L23 of RPV. Although MAb 50 to epitope A at aa 474 showed a neutralizing antibody titer of less than 100 (16), it exhibited inhibition of the cytopathic effect by the wild-type L strain in a high concentration (10%) of MAb 50-rich ascitic fluid by blocking the spread of the virus from cell to cell. In the same β5L01, it has been reported that the domain between aa 451 and 505 of MV-H seems to be the antigenic site required for neutralization, hemadsorption, and hemagglutination activities based on the reactivities of MAbs and chimeric MV-H (12). Also, neutralizing antigenic site II was determined at aa 491 by sequencing a MAb-selected MR mutant (5).

The antibodies to epitopes G on β2L23 and D on β6L01 were moderately detectable in RPV-infected rabbit sera, with geometric means of their c-ELISA titers of 12.1 and 8.0, respectively. On epitope G at aa 310 to 313 of β2L23, aa 313 and 314 have been mapped as neutralizing site I by analysis of selected MR mutants (5). This epitope was also identified by peptide-binding studies (aa 309 to 318) (11, 12). We determined epitope D at aa 548 to 551 next to neutralizing site III mapped on aa 552 by sequencing an MR mutant gene (5).

In the present study, we identified two major neutralizing epitopes, epitope H at aa 383 to 387 and epitope E at aa 587 to 592 on RPV-H. The isolation rates of hybridomas secreting MAbs against these epitopes were higher than those against the other epitopes, since we established four MAbs (1d, 53, 19, and 47) that recognized epitope H and five MAbs (E-1, 32, 39, 61, and 80) that recognized epitope E (16). The isolation rate of hybridomas may reflect the immunogenicity of the antigenic sites. Epitope E near the C terminus of RPV-H is located on the same epitope (aa 587 to 596) of MV-H, which has been previously identified from data on reactivity of a synthetic peptide and MAb (11). According to Liebert et al. (10), the major antigenic site of MV-H is located between residues 368 and 396, which corresponds exactly to the large insertion at β3L23. It has also been reported that a small cysteine cluster region (Cys-381, Cys-386, and Cys-394) at β3L23 of MV was identified as a linear neutralizing and protective epitope (22). We identified the most immunodominant epitope, epitope H at aa 383 to 387, on the same loop in RPV. These results suggest that the loop structure β3L23 formed by disulfide bonds between two β-sheets is a major neutralizing antigenic site in morbilliviruses.

These results indicate that the overall antigenic structures of the H protein in morbilliviruses are similar. Our data also support the hypothetical 3D model of the H protein of morbillivirus (9). In this study, we identified six neutralizing epitopes which are exposed on the surface of the distinct loop structures of RPV-H. Moreover, we demonstrated that two of six epitopes are immunodominant for the induction of neutralizing antibodies in RPV-infected rabbits.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (no. 09660338) from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atabani, S. F., O. E. Obeid, D. Chargelegue, P. Aaby, H. Whittle, and M. W. Steward. 1997. Identification of an immunodominant neutralizing and protective epitope from measles virus fusion protein by using human sera from acute infection. J. Virol. 71:7240-7245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chou, P. Y., and G. D. Fasman. 1974. Prediction of protein conformation. Biochemistry 13:222-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fournier, P., N. H. Brons, G. A. Berbers, K. H. Wiesmuller, B. T. Fleckenstein, F. Schneider, G. Jung, and C. P. Muller. 1997. Antibodies to a new linear site at the topographical or functional interface between the haemagglutinin and fusion proteins protect against measles encephalitis. J. Gen. Virol. 78:1295-1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giraudon, P., and T. F. Wild. 1985. Correlation between epitopes on hemagglutinin of measles virus and biological activities: passive protection by monoclonal antibodies is related to their hemagglutination inhibiting activity. Virology 144:46-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu, A., H. Sheshberadaran, E. Norrby, and J. Kovamees. 1993. Molecular characterization of epitopes on the measles virus hemagglutinin protein. Virology 192:351-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu, A., R. Cattaneo, S. Schwartz, and E. Norrby. 1994. Role of N-linked oligosaccharide chains in the processing and antigenicity of measles virus haemagglutinin protein. J. Gen. Virol. 75:1043-1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hummel, K. B., and W. J. Bellini. 1995. Localization of monoclonal antibody epitopes and functional domains in the hemagglutinin protein of measles virus. J. Virol. 69:1913-1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishii, H., Y. Yoshikawa, and K. Yamanouchi. 1986. Adaptation of the lapinized rinderpest virus to in vitro growth and attenuation of its virulence in rabbits. J. Gen. Virol. 67:275-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langedijk, J. P. M., F. J. Daus, and J. T. van Oirschot. 1997. Sequence and structure alignment of Paramyxoviridae attachment proteins and discovery of enzymatic activity for a morbillivirus hemagglutinin. J. Virol. 71:6155-6167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liebert, U. G., S. G. Flanagan, S. Loffler, K. Baczko, V. ter Meulen, and B. K. Rima. 1994. Antigenic determinants of measles virus hemagglutinin associated with neurovirulence. J. Virol. 68:1486-1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mäkelä, M. J., A. A. Salmi, E. Norrby, and T. F. Wild. 1989. Monoclonal antibodies against measles virus haemagglutinin react with synthetic peptides. Scand. J. Immunol. 30:225-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mäkelä, M. J., G. A. Lund, and A. A. Salmi. 1989. Antigenicity of the measles virus haemagglutinin studied by using synthetic peptides. J. Gen. Virol. 70:603-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malvoisin, E., and F. Wild. 1990. Contribution of measles virus fusion protein in protective immunity: anti-F monoclonal antibodies neutralize virus infectivity and protect mice against challenge. J. Virol. 64:5160-5162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schrag, S. J., P. A. Rota, and W. J. Bellini. 1999. Spontaneous mutation rate of measles virus: direct estimation based on mutations conferring monoclonal antibody resistance. J. Virol. 73:51-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugiyama, M., N. Minamoto, T. Kinjo, N. Hirayama, H. Sasaki, Y. Yoshikawa, and K. Yamanouchi. 1989. Characterization of monoclonal antibodies against four structural proteins of rinderpest virus. J. Gen. Virol. 70:2605-2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugiyama, M., N. Minamoto, T. Kinjo, N. Hirayama, K. Asano, K. Tsukiyama-Kohara, Y. Yoshikawa, and K. Yamanouchi. 1991. Antigenic and functional characterization of rinderpest virus envelope proteins using monoclonal antibodies. J. Gen. Virol. 72:1863-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sugiyama, M., N. Minamoto, T. Kinjo, H. Ito, and K. Yamanouchi. 1996. The nucleotide sequence of the hemagglutinin gene of the LA strain of rinderpest virus, a seed virus strain used for vaccine production in Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 58:769-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sugiyama, M., R. Yoshiki, Y. Tatsuno, S. Hiraga, O. Itoh, K. Gamoh, and N. Minamoto. 1997. A new competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay demonstrates adequate immune levels to rabies virus in compulsorily vaccinated Japanese domestic dogs. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 4:727-730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsukiyama, K., Y. Yoshikawa, H. Kamata, K. Imaoka, K. Asano, S. Funahashi, T. Maruyama, H. Shida, M. Sugimoto, and K. Yamanouchi. 1989. Development of heat-stable recombinant rinderpest vaccine. Arch. Virol. 107:225-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamanouchi, K. 1980. Comparative aspects of pathogenicity of measles, canine distemper, and rinderpest viruses. Jpn. J. Med. Sci. Biol. 33:41-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yilma, T., D. Hsu, L. Jones, S. Owens, M. Grubman, C. Mebus, M. Yamanaka, and B. Dale. 1988. Protection of cattle against rinderpest with vaccinia virus recombinants expressing the HA or F gene. Science 242:1058-1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ziegler, D., P. Fournier, G. A. Berbers, H. Steuer, K. H. Wiesmuller, B. Fleckenstein, F. Schneider, G. Jung, C. C. King, and C. P. Muller. 1996. Protection against measles virus encephalitis by monoclonal antibodies binding to a cystine loop domain of the H protein mimicked by peptides which are not recognized by maternal antibodies. J. Gen. Virol. 77:2479-2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]