Abstract

Dendritic cells are susceptible to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and may transmit the virus to T cells in vivo. Scarce information is available about drug efficacy in dendritic cells because preclinical testing of antiretroviral drugs has been limited predominantly to T cells and macrophages. We compared the antiviral activities of hydroxyurea and two protease inhibitors (indinavir and ritonavir) in monocyte-derived dendritic cells and in lymphocytes. At therapeutic concentrations (50 to 100 μM), hydroxyurea inhibited supernatant virus production from monocyte-derived dendritic cells in vitro but the drug was ineffective in activated lymphocytes. Concentrations of hydroxyurea insufficient to be effective in activated lymphocytes cultured alone strongly inhibited supernatant virus production from cocultures of uninfected, activated lymphocytes with previously infected monocyte-derived dendritic cells in vitro. In contrast, protease inhibitors were up to 30-fold less efficient in dendritic cells than in activated lymphocytes. Our data support the rationale for testing of the combination of hydroxyurea and protease inhibitors, since these drugs may have complementary antiviral efficacies in different cell compartments. A new criterion for combining drugs for the treatment of HIV infection could be to include at least one drug that selectively targets HIV in viral reservoirs.

A growing body of evidence suggests that dendritic cells (DC) are involved in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) propagation to T cells and play a key role in the pathogenesis of HIV infection (5, 8, 9, 22, 23). In vitro, HIV can infect immature monocyte-derived DC; once they have matured, they loose the ability to replicate the virus, but they transmit HIV to T cells very efficiently by coculture (8). A recently described DC-specific membrane protein (DC-SIGN) efficiently promotes infection in trans to CD4 T cells during the antigen presentation process (7). In vivo infection of DC has been demonstrated by isolation of a subset of HIV-infected DC from peripheral blood derived from HIV-infected individuals (22). HIV replication can be detected in DC-derived syncytia at the surface mucosa of the adenoids (5). Finally, the number of DC present in the peripheral blood of HIV-infected patients inversely correlates with the plasma viral load and highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) partially restores the number of peripheral blood DC (9).

Antiretroviral drug efficacy may differ between cell types. For example, protease inhibitors, the most potent anti-HIV drugs in lymphocytes, are severalfold less effective in macrophages (25). On the contrary, hydroxyurea, a ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor, inhibits HIV poorly in activated lymphocytes but is potent in macrophages (20). Inhibition of HIV in terminally differentiated cells, such as DC and macrophages, may be important because these cells are thought to act as viral reservoirs and may be responsible for the failure of HIV eradication attempts (4, 29). Furthermore, these cells probably represent the route of initial infection during sexual, parental, or vertical transmission (3, 30). Among the available antiretroviral drugs, only the efficacy of azidothymidine has been tested on DC (2). In this study, we compared the antiretroviral activity of protease inhibitors and hydroxyurea in DC and in lymphocytes. In addition, we examined the ability of these drugs to limit virus transmission from infected DC to activated lymphocytes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Gaithersburg, Md.) containing 10% heat-inactivated calf serum (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) was used as the culture medium (CM). Immature monocyte-derived DC were obtained as previously described (8), with minor modifications. Monocytes were obtained by 1-h plastic adhesion of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from normal subjects and cultured in CM supplemented with interleukin-4 (Biosource, Camarillo, Calif.) and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (Schering-Plough, Milan, Italy), both at 1,000 IU/ml. After 1 week, floating cells (most of them dendrite shaped) were harvested and an aliquot was used for immunophenotyping by flow cytometry. Cells were stained with fluoresceinated or tri-color-labeled anti-CD11c, -CD80, -CD83, -CD86, and -HLA-DR (Caltag) and anti-CD3, -CD4, and -CD14 (Becton Dickinson) antibodies and analyzed with a FACScalibur (Becton Dickinson) flow cytometer. Cells that were FSChigh, HLA-DR+, CD14−, CD11c+, CD80−, CD83low, and CD86low or CD86− were identified as immature DC. The purity of our preparations was always greater than 80%. CD3+, CD4+, doubly positive, or CD14+ cell contamination was less than 2%. PBMC from normal human subjects were isolated by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation and activated for 48 h with phytohemagglutinin (PHA; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) at 5 μg/ml. For lymphocyte-DC coculture experiments, aliquots of monocyte-depleted PBMC were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium containing 40% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide during DC differentiation and stored in liquid nitrogen. Cocultures were performed with RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum and 50% of the supernatant harvested from DC at the end of differentiation.

Viruses and infection of cells.

PHA-activated PBMC and immature monocyte-derived DC were infected for 90 min with R5X4 (dual-tropic) strain HIVLW (17) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.02 or with R5 (macrophage-tropic) strain HIVBaL at an MOI of 0.002 in 100 μl of RPMI 1640 medium at 37°C. DC were trypsinized for 5 min at 37°C to remove cell-adherent virus. After extensive washes with CM, both cell types were plated at 50,000 cells/well in flat-bottom 96-well plates in 250 μl of CM in the presence of each test drug. Hydroxyurea was obtained from Sigma. Ritonavir and indinavir were generous gifts from Abbott (Campoverde di Aprilia, Latina, Italy) and Merck Sharp & Dohme (Rome, Italy), respectively. DC were cultured with CM containing 50% of the supernatant medium harvested at the end of DC differentiation; activated PBMC medium was supplemented with interleukin-2 at 20 IU/ml (kind gift of Hoffmann-La Roche, Inc., Nutley, N.J.). Identical triplicate wells were set for each experimental condition. At the times indicated in Results, half of the supernatant was collected to determine the p24 concentration and replaced with the same medium containing the various drug concentrations. We performed three separate experiments with HIVLW-infected DC and two separate experiments with HIVBaL-infected DC and HIVLW-infected PBMC.

In DC-lymphocyte coculture experiments, DC were infected with HIVLW and seeded in 96-well plates as described above. Autologous, cryopreserved, monocyte-depleted PBMC were activated with PHA for 48 h and added at a 1:1 ratio to DC 24 h after DC infection. Test drugs were added at the beginning of the coculture.

HIV type 1 p24 antigen was measured in the supernatants by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Coulter, Miami, Fla.). To reduce interexperiment variability in the absolute values of p24 released, the data are presented as percentages of p24 release compared with that of the untreated control. The effects of the drugs on DC maturation were evaluated by incubating 800,000 infected DC in 12-well plates with drugs for 1 week. At the end of the incubation period, cells were harvested and the immunophenotype was characterized by flow cytometry as described previously (15a).

Cell viability at the end of 1 week of incubation was evaluated by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) reduction method (24); the MTT assay results were confirmed by a trypan blue exclusion test. To calculate the antiviral activity of the drugs after the 1-week incubation period, p24 production was normalized to the number of viable cells and presented as a percentage of that of the control (sample without drugs). Drug concentrations inhibiting viral release by 50% (IC50) were calculated by linear regression of p24 production (as a percentage of the control) versus the drug concentration (both on logarithmic scales).

RESULTS

Time course of the antiviral effects of hydroxyurea and indinavir in DC.

First, we analyzed whether HIV-infected DC were productively infected. Evidence that HIV was produced in DC cultures derives from the comparison of the total amount of p24 detected just after infection (virus input) with the p24 amount detected 1 week later (virus output). The total p24 input represents the sum of cell-associated (measured in the cell lysate) plus cell-free (measured in the supernatant) p24 at time zero after infection and washings. In two experiments, the total p24 input amounts were 0.44 and 0.27 ng/106 cells for HIVLW and HIVBaL infections, respectively. After 7 days of culture, the total amounts of p24 released in the supernatant were 1.69 and 1.51 ng/106 cells for HIVLW and HIVBaL infections, respectively. In both cases, the p24 output was greater than the total p24 input, indicating that HIV was newly replicating under our experimental conditions. The low percentage of CD4+ cells (always less than 2%) in the DC preparations and the absence of specific stimuli in the DC cultures able to activate these lymphocytes support the idea that the virus production in these experiments originated from DC and not from contaminating lymphocytes.

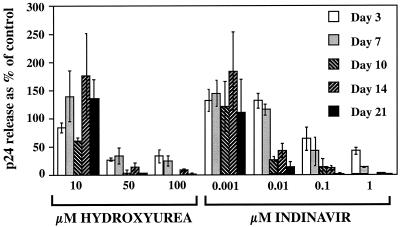

We then examined, in separate, consecutive experiments, the abilities of hydroxyurea and indinavir to inhibit the release of virus from HIVLW-infected DC during a 3-week period. In the experiment whose results are illustrated in Fig. 1, the mean concentration (nanograms per well) of p24 measured in the supernatant of untreated DC increased during the whole time course: 0.03 at day 3, 0.093 at day 7, 0.124 at day 10, 0.503 at day 14, and 3.195 at day 21 after infection. Drugs were used at concentrations corresponding to the plasma therapeutic range (12, 13, 28): hydroxyurea from 10 to 100 μM and indinavir from 0.001 to 1 μM. As shown in Fig. 1, hydroxyurea at 10 μM had little or no antiviral effect, but at 50 and 100 μM, it was able to inhibit virus release from DC. The inhibition was potent from the first week (20 to 30% residual virus release as a percentage of the control) and almost complete thereafter.

FIG. 1.

Time-dependent antiviral effects of hydroxyurea and indinavir in DC. HIVLW-infected DC were incubated in the presence of hydroxyurea or indinavir. The results are presented as percentages of the p24 release of the control (infected cells without drugs). The data represent the means ± the standard deviations of three replicate wells.

The antiviral effect of indinavir was also dose dependent. The drug had no efficacy at a 0.001 μM concentration, but at concentrations of 0.01 to 1 μM, it inhibited virus release from DC.

Comparison of antiviral activity of protease inhibitors and hydroxyurea in DC and lymphocytes.

Based on the previous results, we directly compared the antiviral activity of hydroxyurea and protease inhibitors in parallel experiments. We measured p24 release from both DC and activated lymphocytes on day 7 after infection in order to obtain a consistent comparison between the antiviral efficacy of hydroxyurea and protease inhibitors. We also evaluated the viability of the cells and normalized p24 release to the number of viable cells.

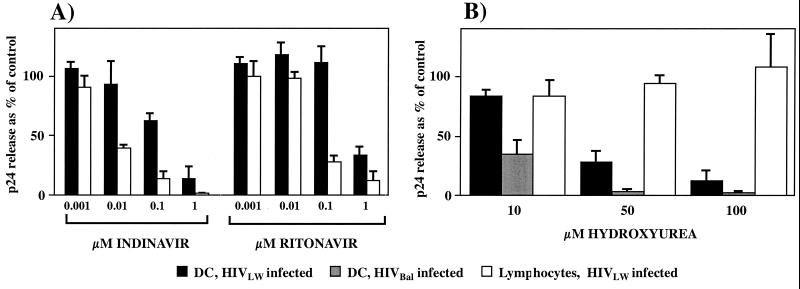

Figure 2A shows the antiviral efficacy of the protease inhibitors indinavir and ritonavir at therapeutic (12, 13) concentrations ranging from 0.001 to 1 μM in HIVLW-infected DC and lymphocytes. The mean amounts of p24 released into the supernatant of DC and lymphocytes in the absence of drugs were 0.315 and 8.59 ng per well, respectively. Both indinavir and ritonavir inhibited HIV in a dose-dependent manner. Virus release in lymphocytes (open bars) was completely inhibited at the maximal concentration of indinavir (1 μM) and almost completely at a similar concentration of ritonavir. In contrast, HIV release was not totally inhibited in DC (black bars) by similar drug concentrations (Fig. 2A). The IC50 for both protease inhibitors was severalfold higher in DC than in lymphocytes (>30-fold and >15-fold for indinavir and ritonavir, respectively) (Table 1). Indinavir appeared to be a more potent HIV inhibitor than ritonavir in DC. In contrast, the calculated IC50 for hydroxyurea in DC (37 μM) was well within the therapeutic range, whereas it was out of the therapeutic range in lymphocytes (Table 1).

FIG. 2.

Antiretroviral efficacy of protease inhibitors indinavir and ritonavir (A) and hydroxyurea (B) in activated lymphocytes and DC. HIV replication was measured by p24 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and normalized to the number of viable cells. The results are presented as percentages of the p24 release of the control (infected cells without drugs). The data represent the means ± the standard deviations of three separate experiments for DC (HIVLW infection) and two separate experiments for lymphocytes and DC (HIVBaL infection).

TABLE 1.

Antiviral drug activity in DC and in lymphocytesa

| Drug | IC50 (μM)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| DC | Lymphocytes | Plasmab | |

| Hydroxyurea | 37 | 100 | 10-100 |

| Indinavir | 0.210 | 0.006 | 0.1-5 |

| Ritonavir | 0.620 | 0.038 | 0.06-0.2 |

We infected DC with R5 strain HIVBaL in an independent experiment to confirm the ability of hydroxyurea to block virus release from DC. HIVBaL replicated at higher levels in DC than did HIVLW (0.775 and 0.315 ng of p24 per well, respectively), even when a lower MOI (0.02 for HIVLW and 0.002 for HIVBaL strain) was used. Although HIVBaL was a more infectious strain, hydroxyurea inhibited it very efficiently, as shown in Fig. 2B. HIVBaL replication was inhibited almost completely by 50 μM hydroxyurea.

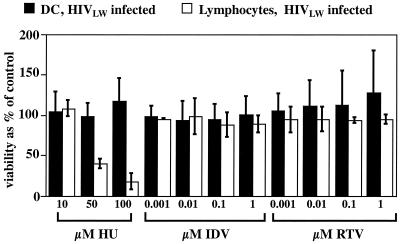

The viability of HIVLW-infected DC and lymphocytes was examined after 1 week of culture in the presence of the test drug to exclude the possibility that the antiviral drugs were inhibiting viral release due to cytotoxic effects. The results presented in Fig. 3 show no decrease in DC or lymphocyte viability after a 1-week incubation in the presence of up to 1 μM indinavir or ritonavir. The viability of HIV-infected DC was also unaffected by hydroxyurea, even at high concentrations, as already observed in macrophages (20). This suggests that the observed differences in the inhibition of virus release were not mediated by toxic effects but possibly due to different antiviral activities of the drugs. In contrast, hydroxyurea significantly reduced the viability of infected lymphocytes. After 1 week of hydroxyurea treatment, only 39% (hydroxyurea at 50 μM) and 17% (hydroxyurea at 100 μM) of the lymphocytes were still viable, compared to the control cells incubated without the drug. When p24 release was normalized with the number of viable cells, hydroxyurea did not appear to affect the amount of p24 release from lymphocytes (Fig. 2B, open bars).

FIG. 3.

Viability of HIVLW-infected DC and lymphocytes after a 1-week incubation in the presence of hydroxyurea (HU), indinavir (IDV), or ritonavir (RTV). Cell viability was measured by the MTT method. The results presented are percentages of the control (infected cells without drugs). The data represent the means ± the standard deviations of three separate experiments for DC and two separate experiments for lymphocytes.

Effects of hydroxyurea and indinavir on DC maturation.

Since infected, mature DC replicate HIV less efficiently than immature DC (8), one could hypothesize that the drugs may reduce virus release from DC by inducing maturation in these cells. To exclude this possibility, we quantified the expression of CD11c, CD80, CD83, CD86, and HLA-DR molecules of HIVLW-infected DC incubated in the presence of hydroxyurea at 100 μM or indinavir at 1 μM (both drug concentrations were able to maximally inhibit virus release from DC). In two separate experiments, we demonstrated that the immunophenotype of DC incubated with the drugs was similar to that of the control incubated without drugs (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Percentage of HIVLW-infected DC expressing the indicated surface markers after 1 week of culture in the presence of the given druga

| Marker | % of cells expressing marker in:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Medium | Hydroxurea at 100 μM | Indinavir at 1 μM | |

| None (isotype control) | 0.99 | 0.63 | 0.81 |

| CD11c | 66.40 | 69.47 | 70.04 |

| CD80 | 15.39 | 14.69 | 15.67 |

| CD83 | 6.46 | 4.72 | 4.28 |

| CD86 | 44.58 | 40.34 | 40.58 |

| HLA-DR | 70.71 | 69.60 | 69.78 |

The data are the means of values from two separate experiments.

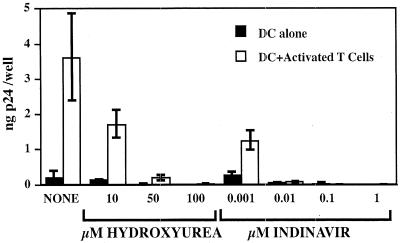

Abilities of hydroxyurea and indinavir to inhibit virus transmission from infected DC to uninfected lymphocytes.

DC transmit HIV infection efficiently to T cells, and this phenomenon may be critical for the spread of HIV in vivo (5, 8, 9, 22, 23). Therefore, we examined whether protease inhibitors and hydroxyurea can affect virus release in cocultures of HIVLW-infected DC and autologous uninfected lymphocytes. Infected DC were preincubated for 24 h in the presence of drugs, and then activated lymphocytes were added at a 1:1 ratio to DC. p24 content in the supernatant was measured 10 days later. In the absence of drugs, p24 release from activated T-cell-DC cocultures was significantly higher than p24 release from DC alone, consistent with efficient virus transmission from infected DC to T lymphocytes (Fig. 4). Hydroxyurea, which had been incapable of blocking virus replication in activated T lymphocytes, strongly inhibited virus transmission from infected DC to T lymphocytes.

FIG. 4.

Antiviral effects of hydroxyurea and indinavir on HIVLW-infected DC cocultured with activated autologous lymphocytes. The amount of p24 released per well in the supernatants was measured 10 days after coculture. The data represent the means ± the standard deviations of three replicate wells.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we provide evidence that hydroxyurea and protease inhibitors have complementary anti-HIV efficacy in DC and lymphocytes. This observation extends our previous demonstration that hydroxyurea is a very potent HIV inhibitor in human macrophages. Inhibition of HIV in DC and macrophages may be quite relevant. Although only a small fraction of the virus is thought to replicate in macrophages and DC, these cells have been determined to be responsible for spreading the initial infection (3, 5, 30). These cells are also suspected to be long-term viral reservoirs (10, 26) capable of rekindling the infection. Hydroxyurea inhibited HIV replication in DC with an IC50 of 37 μM. This value is similar to the mean therapeutic concentration (ca. 45 ± 6 μM) of the drug in plasma (28). In contrast, the IC50 of ritonavir in DC was threefold higher than the peak concentration of the unbound form of this drug in plasma (1).

We can only offer a hypothesis to explain the cell-dependent anti-HIV activity of hydroxyurea and protease inhibitors. Hydroxyurea inhibits ribonucleotide reductase and therefore lowers the intracellular concentration of deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTP). Consequently, DNA synthesis by HIV reverse transcriptase is impaired (6). DC are nonproliferating cells and therefore are expected to have dNTP concentrations lower than those found in activated lymphocytes. Therefore, hydroxyurea might be able to decrease dNTP concentrations in DC to a level sufficient to block reverse transcriptase. Since DC, unlike activated lymphocytes, do not need dNTP for cell division, hydroxyurea would have little or no toxic effect in DC, as observed in our experiments. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the efficiency of hydroxyurea and protease inhibitors in DC is similar to that described in macrophages (20, 25), another class of nondividing cells.

The mechanism underlying the differences in protease inhibitor efficacy in DC and lymphocytes is less clear. It is possible that DC are less permeable to protease inhibitors or more efficient than lymphocytes at transporting protease inhibitors outside the cells, since these drugs are actively transported outside the cell by the P glycoprotein (14, 27), a multidrug resistance protein expressed at a different level in all leukocyte types (15).

Drugs inhibiting HIV in reservoir compartments that are difficult to target by currently used regimens might represent a novel class of antiretrovirals. It might be worthwhile to include these drugs in HAART combinations. HAART combinations comprising hydroxyurea, didanosine, and protease inhibitors have been successfully administered to HIV-infected patients (16, 18, 19, 21); however, the toxicity profile of the combination of hydroxyurea and protease inhibitors is unclear (9a). Although the results of the present study support the concept that the combination of hydroxyurea and protease inhibitors, able to inhibit HIV replication in all susceptible cell compartments, might be most effective at controlling HIV replication, further in vitro research and controlled in vivo studies are required to prove the concept and to study the toxicity of this novel combination.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Jianqing Xu and Georg Varga for their helpful advice on dendritic cell preparation. We also thank Paola Villani for technical support and Sylva Petrocchi for editorial assistance.

This work was supported in part by the Istituto Superiore di Sanità (grant no. 30C.44).

REFERENCES

- 1.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 1998. Antiretroviral agents: American hospital formulary service drug information, p. 543-572. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Bethesda, Md.

- 2.Blauvelt, A., H. Asada, M. W. Saville, V. Klaus-Kovtun, D. J. Altman, R. Yarchoan, and S. I. Katz. 1997. Productive infection of dendritic cells by HIV-1 and their ability to capture virus are mediated through separate pathways. J. Clin. Investig. 100:2043-2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cameron, P. U., M. G. Lowe, F. Sotzik, A. F. Coughlan, S. M. Crowe, and K. Shortman. 1996. The interaction of macrophage and non-macrophage tropic isolates of HIV-1 with thymic and tonsillar dendritic cells in vitro. J. Exp Med. 183:1851-1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finzi, D., J. Blankson, J. D. Siliciano, J. B. Margolick, K. Chadwick, T. Pierson, K. Smith, J. Lisziewicz, F. Lori, C. Flexner, T. C. Quinn, R. E. Chaisson, E. Rosenberg, B. Walker, S. Gange, J. Gallant, and R. F. Siliciano. 1999. Latent infection of CD4+ T cells provides a mechanism for lifelong persistence of HIV-1, even in patients on effective combination therapy. Nat. Med. 5:512-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frankel, S. S., B. M. Wenig, A. P. Burke, P. Mannan, L. D. Thompson, S. L. Abbondanzo, A. M. Nelson, M. Pope, and R. M. Steinman. 1996. Replication of HIV-1 in dendritic cell-derived syncytia at the mucosal surface of the adenoid. Science 272:115-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao, W. Y., A. Cara, R. C. Gallo, and F. Lori. 1993. Low levels of deoxynucleotides in peripheral blood lymphocytes: a strategy to inhibit human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:8925-8928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geijtenbeek, T. B., D. J. Krooshoop, D. A. Bleijs, S. J. van Vliet, G. C. van Duijnhoven, V. Grabovsky, R. Alon, C. G. Figdor, and Y. van Kooyk. 2000. DC-SIGN-ICAM-2 interaction mediates dendritic cell trafficking. Nat. Immunol. 1:353-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Granelli-Piperno, A., E. Delgado, V. Finkel, W. Paxton, and R. M. Steinman. 1998. Immature dendritic cells selectively replicate macrophage-tropic (M-tropic) human immunodeficiency virus type 1, while mature cells efficiently transmit both M- and T-tropic virus to T cells. J. Virol. 72:2733-2737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grassi, F., A. Hosmalin, D. McIlroy, V. Calvez, P. Debre, and B. Autran. 1999. Depletion in blood CD11c-positive dendritic cells from HIV-infected patients. AIDS 13:759-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9a.Havlir, D., P. Gilbert, K. Bennett, A. Collier, M. Hirsch, P. Tebas, E. Adams, D. Goodwin, S. Schnittman, M. K. Holohan, and D. Richman. 2000. Randomized trial of continued indinavir (IDV)/ZDV/3TC v. switch to IDV/ddI/d4T or IDV/ddI/d4T + hydroxyurea in patients with viral suppression. 7th Conf. Retrovir. Opportunistic Infect.

- 11.Ho, D. D., A. U. Neumann, A. S. Perelson, W. Chen, J. M. Leonard, and M. Markowitz. 1995. Rapid turnover of plasma virions and CD4 lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection. Nature 373:123-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu, A., G. R. Granneman, G. Cao, L. Carothers, A. Japour, T. El-Shourbagy, S. Dennis, J. Berg, K. Erdman, J. M. Leonard, and E. Sun. 1998. Pharmacokinetic interaction between ritonavir and indinavir in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2784-2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu, A., G. R. Granneman, G. Witt, C. Locke, J. Denissen, A. Molla, J. Valdes, J. Smith, K. Erdman, N. Lyons, P. Niu, J. P. Decourt, J. B. Fourtillan, J. Girault, and J. M. Leonard. 1997. Multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of ritonavir in human immunodeficiency virus-infected subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:898-905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim, A. E., J. M. Dintaman, D. S. Waddell, and J. A. Silverman. 1998. Saquinavir, an HIV protease inhibitor, is transported by P-glycoprotein. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 286:1439-1445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laupeze, B., L. Amiot, L. Payen, B. Drenou, J. M. Grosset, G. Lehne, R. Fauchet, and O. Fardel. 2001. Multidrug resistance protein (MRP) activity in normal mature leukocytes and CD34-positive hematopoietic cells from peripheral blood. Life Sci. 68:1323-1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15a.Lisziewicz, J., D. I. Gabrilovich, G. Varga, J. Xu, P. D. Greenberg, S. K. Arya, M. Bosch, J. Behr, and F. Lori. 2001. Induction of potent human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific T-cell-restricted immunity by genetically modified dendritic cells. J. Virol. 75:7621-7628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lisziewicz, J., H. Jessen, D. Finzi, R. F. Siliciano, and F. Lori. 1998. HIV-1 suppression by early treatment with hydroxyurea, didanosine, and a protease inhibitor. Lancet 352:199-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lori, F., L. Hall, P. Lusso, M. Popovic, P. Markham, G. Franchini, and M. S. Reitz, Jr. 1992. Effect of reciprocal complementation of two defective human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) molecular clones on HIV-1 cell tropism and virulence. J. Virol. 66:5553-5560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lori, F., H. Jessen, J. Lieberman, D. Finzi, E. Rosenberg, C. Tinelli, B. Walker, R. F. Siliciano, and J. Lisziewicz. 1999. Treatment of human immunodeficiency virus infection with hydroxyurea, didanosine, and a protease inhibitor before seroconversion is associated with normalized immune parameters and limited viral reservoir. J. Infect. Dis. 180:1827-1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lori, F., M. G. Lewis, J. Xu, G. Varga, D. E. Zinn, C. Crabbs, W. Wagner, J. Greenhouse, P. Silvera, J. Yalley-Ogunro, C. Tinelli, and J. Lisziewicz. 2000. Control of SIV rebound through structured treatment interruptions during early infection. Science 290:1591-1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lori, F., A. Malykh, A. Cara, D. Sun, J. N. Weinstein, J. Lisziewicz, and R. C. Gallo. 1994. Hydroxyurea as an inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus-type 1 replication. Science 266:801-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lori, F., E. Rosenberg, J. Lieberman, A. Foli, R. Maserati, E. Seminari, F. Alberici, D. Padrini, B. Walker, and J. Lisziewicz. 1999. Hydroxyurea and didanosine long-term treatment prevents HIV breakthrough and normalizes immune parameters. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 15:1333-1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patterson, S., M. S. Roberts, N. R. English, S. E. Macatonia, M. N. Gompels, A. J. Pinching, and S. C. Knight. 1994. Detection of HIV DNA in peripheral blood dendritic cells of HIV-infected individuals. Res. Virol. 145:171-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patterson, S., S. P. Robinson, N. R. English, and S. C. Knight. 1999. Subpopulations of peripheral blood dendritic cells show differential susceptibility to infection with a lymphotropic strain of HIV-1. Immunol. Lett. 66:111-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pauwels, R., J. Balzarini, M. Baba, R. Snoeck, D. Schols, P. Herdewijn, J. Desmyter, and E. De Clercq. 1988. Rapid and automated tetrazolium-based colorimetric assay for the detection of anti-HIV compounds. J. Virol. Methods 20:309-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perno, C. F., F. M. Newcomb, D. A. Davis, S. Aquaro, R. W. Humphrey, R. Calio, and R. Yarchoan. 1998. Relative potency of protease inhibitors in monocytes/macrophages acutely and chronically infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J. Infect. Dis. 178:413-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tacchetti, C., A. Favre, L. Moresco, P. Meszaros, P. Luzzi, M. Truini, F. Rizzo, C. E. Grossi, and E. Ciccone. 1997. HIV is trapped and masked in the cytoplasm of lymph node follicular dendritic cells. Am. J. Pathol. 150:533-542. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Sandt, I. C., C. M. Vos, L. Nabulsi, M. C. Blom-Roosemalen, H. H. Voorwinden, A. G. de Boer, and D. D. Breimer. 2001. Assessment of active transport of HIV protease inhibitors in various cell lines and the in vitro blood-brain barrier. AIDS 15:483-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Villani, P., R. Maserati, M. B. Regazzi, R. Giacchino, and F. Lori. 1996. Pharmacokinetics of hydroxyurea in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type I. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 36:117-121. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Zhang, L., B. Ramratnam, K. Tenner-Racz, Y. He, M. Vesanen, S. Lewin, A. Talal, P. Racz, A. S. Perelson, B. T. Korber, M. Markowitz, and D. D. Ho. 1999. Quantifying residual HIV-1 replication in patients receiving combination antiretroviral therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 340:1605-1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu, T., H. Mo, N. Wang, D. S. Nam, Y. Cao, R. A. Koup, and D. D. Ho. 1993. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of HIV-1 patients with primary infection. Science 261:1179-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]