Abstract

Mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) is transcribed at high levels in the lactating mammary gland to ensure transmission of virus from the milk of infected female mice to susceptible offspring. We previously have shown that the transcription factor CCAAT displacement protein (CDP) is expressed in high amounts in virgin mammary gland, yet DNA-binding activity for the MMTV long terminal repeat (LTR) disappears as mammary tissue differentiates during lactation. CDP is a repressor of MMTV expression and, therefore, MMTV expression is suppressed during early mammary gland development. In this study, we have shown using DNase I footprinting and electrophoretic mobility shift assays that there are at least five CDP-binding sites in the MMTV LTR upstream of those previously described in the promoter-proximal negative regulatory element (NRE). Single mutations in two of these upstream sites (+691 or +692 and +735 relative to the first base of the LTR) reduced CDP binding to the cognate sites and elevated reporter gene expression from the full-length MMTV LTR. Combination of a mutation in the promoter-distal NRE with a mutation in the proximal NRE gave approximately additive increases in LTR-reporter gene activity, suggesting that these binding sites act independently. Mutations in several different CDP-binding sites allowed elevation of reporter gene activity from the MMTV promoter in the absence and presence of glucocorticoids, hormones that contribute to high levels of MMTV transcription during lactation by activation of hormone receptor binding to the LTR. In addition, overexpression of CDP in transient-transfection assays suppressed both basal and glucocorticoid-induced LTR-mediated transcription in a dose-dependent manner. These data suggest that multiple CDP-binding sites contribute independently to regulate binding of positive factors, including glucocorticoid receptor, to the MMTV LTR during mammary gland development.

Mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) is transmitted from the milk of virus-infected female mice to susceptible offspring (20). Ingested MMTV infects gut-associated B cells, which subsequently produce a virally encoded superantigen (Sag) at the cell surface in conjunction with major histocompatibility type II protein (28, 31). Sag-presenting B cells interact with T cells carrying specific variable regions on the β-chain of the T-cell receptor (1, 45). Sag stimulation through the T-cell receptor elicits the production of cytokines that result in the amplification in the number of infected lymphocytes that traffic the virus to the mammary glands during puberty (26, 58). Amplification of MMTV expression within the mammary gland is dependent on elevated levels of hormones during pregnancy and lactation, and steroid hormones are known to activate virus transcription from the hormone response element (43, 51, 56). Therefore, the MMTV life cycle requires transcriptional control of virus expression in at least three cell types: B cells, T cells, and mammary gland cells.

MMTV induces mammary carcinomas and, at a lower frequency, T-cell lymphomas in mice (6, 19, 35, 48). MMTV variants that induce exclusively T-cell lymphomas have a deletion of 350 to 500 bp in the U3 region of the long terminal repeat (LTR) (7, 30, 35, 47) that negatively regulates viral transcription (12, 30). At least two transcriptional repressors, special AT-rich binding protein 1 (SATB1) and CCAAT displacement protein (CDP), bind to this negative regulatory element (NRE) (40). SATB1 is most abundant in thymus, but it also is expressed in a number of tissues that are semipermissive or nonpermissive for MMTV expression (17, 40). CDP (also known as Cux in mice, Clox in dogs, and Cut in Drosophila) (4, 9, 11, 64) is expressed in most undifferentiated tissues, yet during differentiation CDP expression is greatly diminished (3, 4, 60, 64). CDP downregulation also is observed during mammary gland development, and both CDP and SATB1 binding activities for the MMTV LTR are undetectable in lactating mammary gland (72). Since MMTV expression is highest during lactation for optimal viral transmission (27, 59), virus expression in the mammary gland appears to be reciprocally related to the expression of the repressors SATB1 and CDP.

Recently, we mapped two CDP-binding sites within the promoter-proximal region of the MMTV NRE (72). Mutations at either of these sites was sufficient to elevate basal expression of an MMTV LTR-reporter gene, although mutations in the more distal site (+837 relative to the first base of the LTR or −358 upstream of the transcriptional start site) appeared to elicit a greater effect than those at +916 (−279). Reporter plasmids containing a combination of these two mutations showed similar expression to those with a single mutation at +837 (72). Additional CDP-binding sites in the MMTV LTR (previously called UBP) have been proposed in the distal NRE (12). Functional studies in transgenic mice (40) and transfection experiments in tissue culture (30) suggested that the proximal and distal NREs contribute independently to MMTV transcriptional suppression, yet elimination of the distal NRE appeared to have a greater effect than removal of the proximal NRE (30). Also, previous experiments indicated that CDP repression was still active in the mammary gland during pregnancy, when positive regulators, such as glucocorticoid receptor (GR), upregulate MMTV transcription (57, 59, 72).

In the present study, we have mapped at least five additional binding sites within the negative regulatory region of the MMTV LTR (Fig. 1). Four of these binding sites mapped to the region previously described as the promoter-distal NRE and one site mapped to the region between the distal and proximal NREs (12, 30). Substitution mutations in two of these sites were shown to elevate both basal and glucocorticoid-induced reporter gene expression from the MMTV LTR in stable transfection assays, and CDP overexpression could partially reduce hormone induction from the MMTV promoter. These data suggest that CDP blocks the action of positively acting transcriptional factors, including GR, to tightly limit MMTV expression during early developmental stages of the mammary gland.

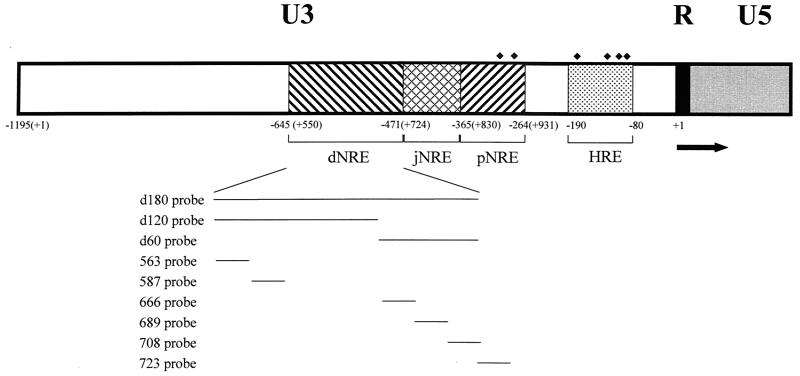

FIG. 1.

Diagram of the MMTV LTR. The LTR is divided into U3, R, and U5 regions, and the arrow indicates the start of transcription at the first base of the R region. The promoter-proximal NRE (pNRE), promoter-distal NRE (dNRE), the junction between pNRE and dNRE (jNRE), and the hormone response element (HRE; containing four GR-binding sites) are shown by boxes with different hatch marks. There also are two GR-binding sites (GRE 5 and 6) within the pNRE (22). GR-binding sites are shown by small black diamonds. The first base of the LTR is shown as +1 (−1195 from the start of transcription). The relative positions of probes used in this study are shown below the LTR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Nuclear extract preparation and electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs).

Large-scale preparations of nuclear extracts from cell lines were obtained essentially as described by Dignam et al. (18) and modified by Liu et al. (40). Small-scale preparations of nuclear extracts were obtained using the method of Olnes and Kurl (50) with some modifications. Cells from one confluent plate (107 cells) were harvested and washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline. The washed cells were transferred to a microcentrifuge tube and incubated in 400 μl of buffer I (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 10 mM KCl, 0.01 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 0.2 μg of pepstatin A/ml) at 4°C for 15 min to induce swelling. Nonidet P-40 (Sigma) was added to 0.6% (260 μl of a 2% solution) to lyse the cells. Nuclei were then collected by centrifugation in a microcentrifuge at 200 × g for 10 min at room temperature. The nuclear pellet was washed with buffer I to remove the remaining detergent prior to addition of 200 μl of buffer II (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 0.4 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF, 0.2 μg of pepstatin A/ml) to extract the nuclear proteins. Finally, the extract was separated from nuclear debris by centrifugation at 9,500 × g for 10 min at 4°C and quick-frozen in aliquots using liquid nitrogen.

EMSAs were performed as described by Liu et al. (40), except that labeled oligomers were bound to CDP in buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 25 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 ng of bovine serum albumin per μl, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.1 μg of poly(dI-dC) per μl, 5% glycerol, and protease inhibitors. Competition assays were conducted as described for EMSAs, except that excess amounts of unlabeled DNA fragments were incubated with the reaction mixture at 4°C for 10 min before the addition of labeled probes. Prior to the addition of labeled probes, 1 μl (1:10 dilution) of rabbit anti-CDP sera was incubated with an EMSA reaction mixture at 4°C for 25 min. The preparation of rabbit antisera specific for CDP has been described previously (39). The oligomers used as probes in EMSAs were as follows: 5" GAA GTA AAA AAG GGA AAA AAG AG 3" and its complement (563); 5" GTT TTT GTC AAA ATA GGA GAC AG 3" and its complement (587); 5" CCT TAC CAT ATA CAG GAA GAT AT 3" and its complement (666); 5" GAC TTA AAT TGG GAT AGG TGG GT 3" and its complement (689); 5" GGG TTA CAG TCA ATG GCT ATA AA 3" and its complement (708); 5" GCT ATA AAG TGT TAT ATA GAT CC 3" and its complement (723). Annealing of the complementary oligomers gave a 1-bp overhang.

DNase I footprinting assays.

Binding conditions for DNase I footprinting experiments were the same as those described for EMSAs, except that samples contained purified bacterially expressed CDP representing the C-terminal two-thirds of the protein (CR2-Cterm) (38). The bacterially expressed full-length CDP protein is not soluble (72). Procedures for purification of the CDP recombinant protein, which have been described elsewhere (39), were performed according to standard methods (33, 61). Briefly, bacterial cultures were induced with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 4 h, pelleted, and lysed by sonication in phosphate-buffered saline, 1% Triton X-100, 100 mM EDTA, 10 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 0.32 μg of pepstatin A per ml, 10 μg of leupeptin per ml, and 2 μg of aprotinin per ml. After sonication, insoluble material was removed by centrifugation and the supernatant was mixed with a 50% slurry of glutathione-agarose beads (Sigma) on a rotating wheel. The beads were washed twice in wash buffer (phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% Triton X-100, 10 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 0.32 μg of pepstatin A per ml, 10 μg leupeptin per ml, and 2 μg of aprotinin per ml) and once in cleavage buffer I (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 0.32 μg of pepstatin A per ml, 10 μg leupeptin per ml, and 2 μg of aprotinin per ml). Beads were resuspended in cleavage buffer II (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2), and 20 U of thrombin (Sigma) was added. After incubation for 1 h at room temperature, the beads were washed in cleavage buffer I (1 ml) and analyzed on sodium dodecyl sulfate-containing polyacrylamide gels. EMSAs with the recombinant purified protein have been described previously (39). Conditions for footprinting assays have been described elsewhere (72).

Plasmid constructs.

The CDP expression vector pRc/CMV-CDP was described previously (38, 72). The substitution mutations 735 and 837 were introduced into the MMTV C3H LTR in the pC3H-LUC vector (previously called pLC-LUC) by PCR-based mutagenesis as described by Higuchi (29) and modified by Bramblett et al. (12). The nomenclature system used here corresponds to numbering from the first base of the MMTV LTR as reported by Majors and Varmus (44). In plasmids that contain two mutations, for example, p735/837-LUC, the p837-LUC plasmid previously described as containing a mutation at +835 (72), was used as the template to introduce the second mutation. The substitution mutations 691 and 692 were introduced by inverse PCR. The reactions were performed in 50-μl volumes using the Expand Long-Template PCR system (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany). To remove the parental plasmid DNA, the PCR mixtures were incubated with 2 μl of DpnI at 37°C for at least 4 h. The correct PCR product was recovered from agarose gels, the ends of the purified fragment were phosphorylated using T4 polynucleotide kinase (NEB), and then a ligation was performed. The substitution mutation 838S4 was introduced into the target site of the plasmid using a pair of complementary oligonucleotides as adapted from Stratagene's QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit. PCRs with mixtures containing 125 ng of each oligonucleotide and 10 to 50 ng of parental plasmid in 50-μl volumes were performed to generate double-stranded circular DNA that contained the mutations. PfuTurbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) (2.5 U) was used in PCR as follows: 15 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 55°C for 1 min, and extension at 68°C for 12 min, followed by a final extension step at 68°C for 10 min. To remove the parental plasmid DNA, the reaction mixture was incubated with 2 μl of DpnI at 37°C for at least 4 h and then used for bacterial transformation. The following primers were used in the construction of mutant CDP-binding sites: 5" GCT ATA AAG TGT GCT CGA GAT CC 3" and its complement (m735); 5" ACC TTG GGA TAG GTG GG 3" and a reverse primer that extends in the opposite direction, 5" ACC TCA TAT CTT CCT GTA TAT GG 3" (m691); 5" AAC TGG GAT AGG TGG GTT ACA G 3" and a reverse primer that extends in the opposite direction; 5" CAG GTC ATA TCT TCC TGT ATA TGG 3" (m692); and 5" CAA CAG GTA CAT GAC TAC ATC TAT CTA GGA ATG CAC 3" and its complement (m838S4).

Cell lines and transfections.

The culture of XC cells has been described by Wrona et al. (69). Culture of NMuMG and HC11 mammary cells was performed according to the methods described by Zhu et al. (72). The day prior to transfection, cells were treated with trypsin and replated in growth medium at approximately 2 × 105 cells/35-mm well and incubated overnight until the cells were ca. 50% confluent. Subsequently, 4 μg of the test plasmid and 1 μg of pcDNA3 containing the Geneticin resistance gene in 0.5 ml of RPMI medium without serum were added to 12 μl of DMRIE-C reagent (Life Technologies) in an equal amount of medium, mixed, and incubated at room temperature for 45 min. The cells were washed with RPMI, and then the DNA solution was incubated with the cells for 7 h at 37°C prior to adding 1 ml of complete RPMI with 20% fetal bovine serum. After further incubation for 48 h, cells were selected in 1 mg of Geneticin (Life Technologies) per ml for 3 weeks. Each of the six wells containing ca. 70 colonies was pooled and assayed for luciferase activity. The luciferase readings were normalized for DNA uptake in each pool by using a quantitative PCR assay with primers specific for the C3H MMTV LTR (+155, 5" GGC ATA GCT CTG CTT TGC 3"; and −548, 5" TAC TTC TAG GCC TGT GGT CA 3") (70, 71). For transient-transfection assays, 5-μg aliquots of the test plasmids were added to plates in triplicate and cells were harvested for reporter activity after 48 h.

Reporter gene assays.

Luciferase assays were performed using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, tissue culture cells were harvested 48 h after transfection and washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline. The pellets were resuspended in 1× passive lysis buffer followed by three rounds of freeze-thaw cycles using dry ice-ethanol and 37°C baths. The cell lysate was separated from insoluble debris by centrifugation at 9,500 × g for 5 min at 4°C in a microcentrifuge. The protein concentration of the supernatant was determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay system by comparing samples to a standard of bovine serum albumin (Bio-Rad). The firefly luciferase activity is reported in relative light units. Such values were normalized for DNA uptake as determined by the activity of a cotransfected reporter gene.

Western blotting.

Conditions for Western blot analysis and antibody to CDP (CR2-Cterm) have been described previously (39, 72). Antibody specific for actin was obtained from Sigma.

RESULTS

Multiple CDP-binding sites upstream of the proximal NRE in the MMTV LTR.

Our previous results have shown that there are two CDP-binding sites in the proximal NRE (72). Disruption of CDP binding to the proximal NRE elevated reporter gene expression from the MMTV LTR. However, MMTV variants that cause T-cell lymphomas invariably lose the entire NRE region, including the distal NRE (7, 30, 35, 47), suggesting that loss of the distal elements is critical for acquisition of lymphomagenic capacity. Therefore, we used DNase I footprinting assays to determine the number and location of additional CDP-binding sites in the MMTV LTR (Fig. 1). DNase I footprinting experiments were performed using bacterially expressed, purified CDP (CR2-Cterm) (38) and an end-labeled 180-bp fragment from the distal NRE (data not shown). Three CDP-protected regions (+679 to +685, +692 to +704, and +714 to +721) were detected using the upper-strand probe, and two additional protected regions (+565 to +584 and +620 to +634) were detected using the lower-strand probe. These regions did not overlap due to the resolution of the gels. Thus, the 180-bp fragment was further divided (5" to 3") into 120- and 60-bp fragments.

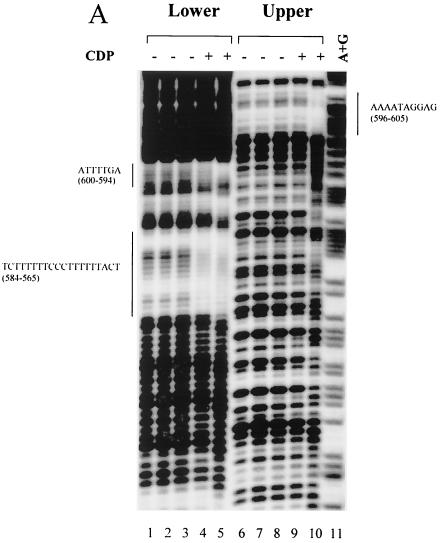

Using the 120-bp fragment, one region (+596 to +605) was protected on both strands (Fig. 2A). A second protected region (+565 to +584) was detected on the lower strand of both the 120-bp and 180-bp probes. DNase I footprinting of the 60-bp fragment showed two protected regions (+692 to +702 and +716 to +722) on the upper strand and two protected regions (+691 to +702 and +682 to +688) on the lower strand (Fig. 2B). The region +692 to +702 was protected using both strands of the 60-bp probe as well as the 180-bp probe, whereas the region +682 to +688 was protected using the lower strand of the 60-bp probe and protected partially on the upper strand of the 180-bp probe. Similarly, the region +716 to +722 was protected on the upper strand of the 60-bp probe and the upper strand of the 180-bp probe. Using EMSAs with nuclear extracts, CDP binding to the 60-bp, but not the 120-bp, fragment was detectable (data not shown). This result suggests that the 120-bp distal NRE fragment contains weaker sites that do not bind CDP when the concentration of the protein is limiting. Together, these results suggest that there is a strong CDP-binding site in the region from +691 to +702 among four weaker CDP-binding sites in the distal NRE (summarized in Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

DNase I footprinting of the dNRE in the MMTV LTR. (A) Footprinting with the 120-bp dNRE fragment. The 120-bp fragment was end labeled on the lower strand (lanes 1 to 5) or the upper strand (lanes 6 to 10). Lane 11 shows Maxim-Gilbert sequencing reactions of the 120-bp fragment. Bacterially produced and purified CDP (CR2-Cterm) was used in reactions shown in lanes 4 and 9 (4 μg) and in lanes 5 and 10 (8 μg) with 0.8 U of DNase I/ml. The amount of DNase I was titrated in lanes without CDP (lanes 1 and 6, 0.2 U/ml; lanes 2 and 7, 0.4 U/ml; lanes 3 and 8, 0.6 U/ml). Reactions were analyzed on an 8% polyacrylamide gel under denaturing conditions. The protected regions are shown on each side of the gel; the numbers in parentheses indicate the location of the protected regions relative to the first base of the C3H MMTV LTR. (B) Footprinting with the 60-bp dNRE fragment. The 60-bp fragment was end labeled on the lower strand (lanes 2 to 6) or the upper strand (lanes 7 to 10). Lane 1 shows Maxim-Gilbert sequencing reactions of the 60-bp fragment. Bacterially produced and purified CDP (CR2-Cterm) was used in reactions shown in lane 8 (4 μg), lanes 5 and 9 (8 μg), and lanes 6 and 10 (16 μg) with 0.8 U of DNase I/ml. The amount of DNase I was titrated in lanes without CDP (lane 2, 0.2 U/ml; lane 3, 0.4 U/ml; lanes 4 and 7, 0.6 U/ml). (C) Summary of CDP-protected sequences from panels A and B. The brackets above the sequence indicate the protected regions using the upper strand probes, and brackets below the sequence are for the lower strand probes. The numbers indicate the location of the protected regions relative to the first base of the C3H MMTV LTR.

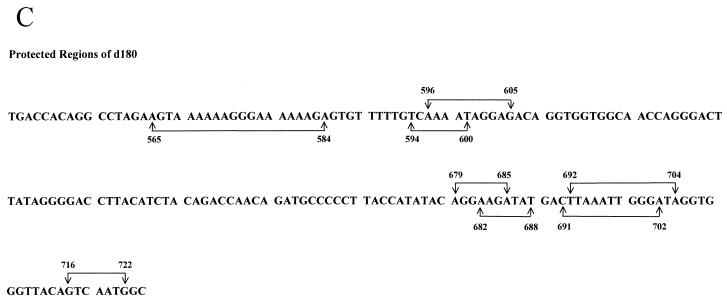

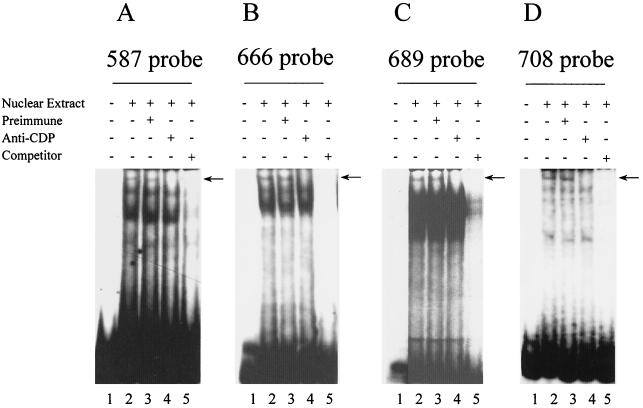

To confirm these mapping results with full-length CDP, NMuMg cell extract was used to perform EMSAs (Fig. 3 and data not shown) with labeled 24-bp oligomers spanning different CDP protected regions as probes (for location, see Fig. 1). A high-molecular-mass band was detected with oligomers 587 (Fig. 3A), 666 (Fig. 3B), 689 (Fig. 3C), and 708 (Fig. 3D). Anti-CDP sera (lane 4) and unlabeled homologous competitors (lane 5) abrogated the complex near the top of the gel, consistent with specific CDP binding. However, the intensity of the CDP-specific band was weak. CDP is an unusual transcription factor of ≈200 kDa with four different, independent DNA-binding domains, and we have observed previously that CDP binds poorly to small oligomers in the proximal NRE (40). The observed binding is much stronger when probes are longer and contain multiple binding sites that may foster cooperative binding (see Fig. 5). Full-length CDP binding to the 563 probe was not detected under the same binding conditions (data not shown), suggesting that this protected region is a weak binding site that requires the higher concentrations of CDP protein found in purified preparations or cooperativity with adjacent sites for binding of endogenous CDP protein. Alternatively, this site may be recognized only by the purified bacterially expressed CR2-Cterm protein. Other binding complexes observed with these probes were not pursued in this study.

FIG. 3.

CDP binding to different oligomers in the dNRE. Nuclear extracts from NMuMg mammary cells (8 μg) were used in EMSAs prior to analysis on 4% polyacrylamide nondenaturing gels. Reactions were incubated without nuclear extracts (lane 1) or with nuclear extracts (lanes 2 to 5) prior to the addition of preimmune serum (lane 3 only), anti-CDP serum (lane 4 only), or a 100-fold excess of unlabeled homologous competitors (lane 5 only). Four 24-bp oligomers containing individual CDP sites which start at positions +587 (A), +666 (B), +689 (C), and +708 (D) were end labeled (ca. 105 cpm or 100 fmole) and added to reaction mixtures prior to gel analysis. The arrows give the position of CDP-specific complexes.

FIG. 5.

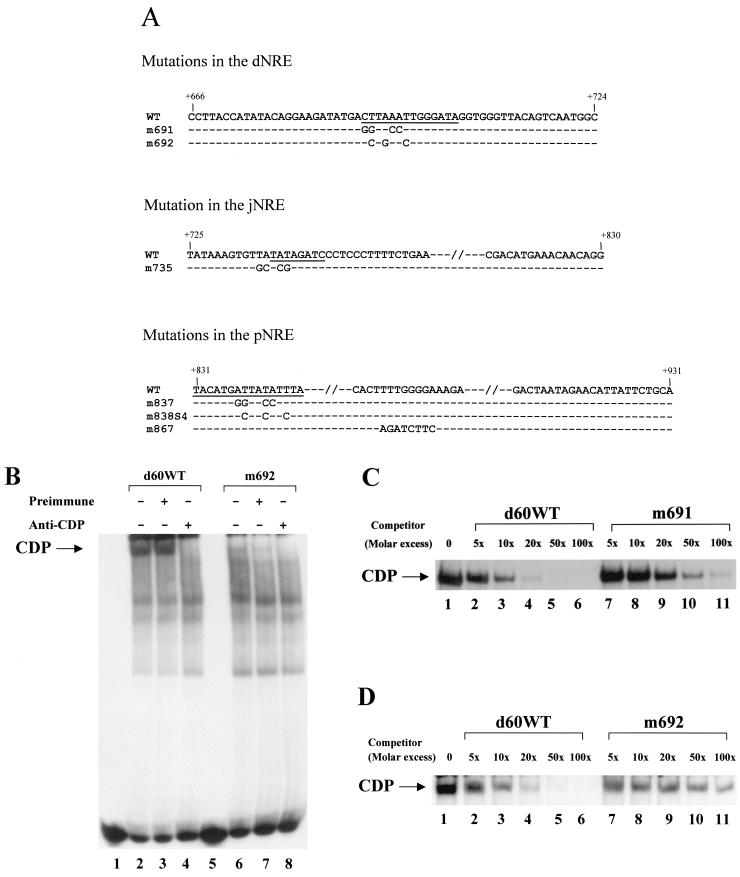

Analysis of CDP binding to mutant dNRE probes. (A) CDP-binding-site mutations in the MMTV LTR. The sequences of the wild-type C3H MMTV in the 60-bp fragment in the dNRE (+666 to +724), the junction between the pNRE and dNRE (+725 to +830), and the pNRE (shown from +831 to +931 relative to the start of the LTR) are shown. In some cases, only a partial sequence is given (indicated by parallel hatch marks). The sequence changes introduced by mutagenesis have been indicated, and unaltered bases are shown by dashes. The underlined sequences indicate the regions protected from DNase I digestion. (B) Binding of CDP to mutant or wild-type probes from the dNRE. Nuclear extracts from HC11 mammary cells (400 ng) were incubated with wild-type (d60WT) or mutant (m692) d60 probes (2 × 104 cpm) prior to analysis on nondenaturing 4% polyacrylamide gels.The wild-type 60-bp fragment or mutant fragments (ca. 5.0 fmole) from the same region were end labeled and analyzed on gels without nuclear extract (lanes 1 and 5) or with nuclear extracts (all other lanes). In some reactions, extracts were incubated with preimmune (lanes 3 and 7) or anti-CDP (lanes 4 and 8) sera. (C and D) Competition of mutant oligomers containing a mutation at +691 (C), or +692 (D) for CDP binding to wild-type probe. Wild-type labeled oligomer was incubated in reaction mixtures containing the indicated amounts of unlabeled wild-type (lanes 2 to 6) or mutant (lanes 7 to 11) oligomers.

An additional CDP-binding site between the distal and proximal NREs (TATAGATC) was predicted using the TransFac software (68). Binding to the region between the distal and proximal NREs was also determined by EMSAs (Fig. 4A). A high-molecular-mass complex was detected after incubation of the 24-bp probe with HC11 mammary cell extract (lane 2). This complex was abolished by the addition of antisera specific for CDP (lane 4), but not by preimmune serum (lane 3). Thus, CDP also binds to a site, designated the junction NRE (jNRE), between the distal and proximal NREs. The diversity of CDP-binding sites has been previously noted (5).

FIG. 4.

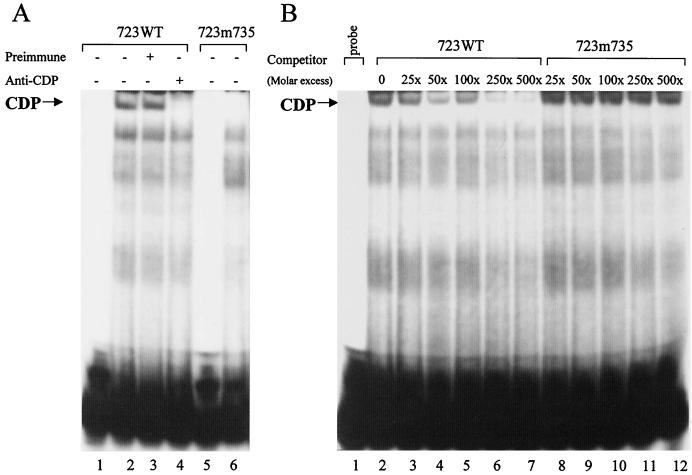

A CDP-binding site between the dNRE and pNRE in the MMTV LTR. Nuclear extract (7 μg) from HC11 mammary cells was used in EMSAs prior to analysis on 4% polyacrylamide nondenaturing gels. (A) EMSA using oligomer probes with or without a CDP-binding site mutation. Oligomers spanning the wild-type (723WT) or mutant (723m735) CDP-binding site were labeled, and ca. 100 fmole of probe was incubated with nuclear extract prior to gel analysis. In some cases, preimmune or CDP-specific sera were added to the nuclear extract prior to addition of the probe. Reactions without added protein are shown for the 723WT and 723m735 probes in lanes 1 and 5, respectively. (B) Competition of unlabeled wild-type or mutant oligomers for CDP binding to the labeled wild-type probe. Approximately 105 cpm (ca. 100 fmole) of wild-type double-stranded oligomer (723WT) was used in an EMSA with a 25- to 500-fold excess of unlabeled homologous (lanes 3 to 7) or heterologous (723m735; lanes 8 to 12) double-stranded oligomer (plus strand, 5" GCT ATA AAG TGT TAT ATA GAT CC 3").

Mutational analysis of CDP-binding sites upstream of the proximal NRE.

We next performed mutational analysis based on the information derived from DNase I footprinting and EMSAs to investigate the function of CDP binding to the distal NRE. Mutagenesis of CDP-binding sites in the proximal NRE suggested that disruption of a single binding site was sufficient to elevate reporter gene expression from the MMTV LTR (72). Because extensive mutagenesis has the potential disadvantage of introducing novel binding sites, we first introduced mutations into a binding site in the distal NRE with apparent high affinity for CDP. To determine the relative affinities among the binding sites in the distal NRE, competition experiments were performed (data not shown), and a site spanning the sequence from +691 to +702 was chosen as the target site.

Two different mutations (for sequence, see Fig. 5A) starting at positions +691 and +692 were introduced into the 60-bp distal NRE probe (d60) (for location, see Fig. 1). Nuclear extract from HC11 mammary cells contained CDP that bound to the wild-type (WT) d60 probe, and this binding was abolished in the presence of CDP-specific antibody (Fig. 5B, compare lanes 2 and 3 with lane 4). Both mutations greatly reduced binding to the 60-bp dNRE probe (Fig. 5B, lane 6, and data not shown). The residual band was shown to be CDP, as demonstrated by ablation with specific antibody (lane 8). To determine the relative affinities of CDP for mutant dNRE-binding sites, we performed EMSAs with the labeled wild-type 60-bp dNRE fragment in the presence of increasing amounts of unlabeled wild-type or mutant fragments (Fig. 5C and D). Phosphorimager analysis showed that a sevenfold excess of wild-type competitor was necessary to reduce CDP binding by 50%, whereas a ca. 50-fold excess of mutant competitor was required to achieve the same amount of competition. This result confirmed that substitution mutations in this region greatly reduced CDP binding to the 3" end of the distal NRE.

A mutation was introduced into the CDP-binding site in the jNRE (for sequence, see Fig. 5A). Using a wild-type 24-bp probe (723 WT), we confirmed that the 4-bp mutation at position +735 virtually eliminated CDP binding (Fig. 4A, lane 6). Competition assays were used to estimate relative affinity of the mutant sites for CDP (Fig. 4B). Phosphorimager analysis with the 4-bp mutation showed that 90% of CDP binding was observed with a 500-fold excess of mutant competitor, whereas 50% binding was obtained with a 30-fold excess of wild-type competitor.

Effect of mutant CDP-binding sites on basal MMTV transcription in mammary cells.

Our previous results indicated that mutation of either CDP-binding site in the proximal NRE was sufficient to elevate reporter gene transcription from the MMTV LTR in HC11 mammary cells (72). CDP mutations in the dNRE and jNRE were introduced into the entire LTR sequence upstream of firefly luciferase and then transfected into HC11 cells in the presence of a coselected marker plasmid. Following drug selection, a large pool of transfectants was then assayed for luciferase activity and normalized to the value obtained with wild-type LTR reporter transfectants (Fig. 6).

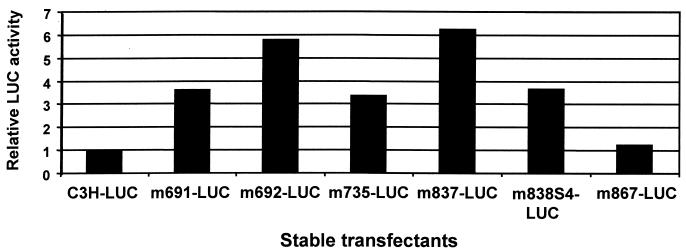

FIG. 6.

Effect of substitution mutations on MMTV LTR-reporter activity in stable transfection assays in HC11 mammary cells. Transfections were performed using DMRIE-C reagent. Pooled colonies obtained for each plasmid construct were assayed for luciferase activity, and the results were normalized for the amount of transfected DNA. Results for mutants are reported relative to those obtained with wild-type LTR constructs in the same assay (assigned a value of 1.0). The results shown represent the average of two independent experiments.

These experiments revealed that mutations in the CDP-binding site at +691 and +692 elevated basal expression from the MMTV LTR from three- to sixfold, whereas the 4-bp mutation at position +735 elevated expression approximately threefold. Comparisons with previously described mutations in the proximal NRE showed that a mutation in the CDP-binding site at +837 elevated reporter activity by sixfold, and a similar mutation at +838 elevated expression three- to fourfold. A nearby mutation at +867 that did not affect CDP binding had no effect. Therefore, like CDP mutations in the proximal NRE, disruption of a single binding site in the distal NRE (+691/692) or between the distal and proximal NREs (+735) was sufficient to (at least partially) relieve suppression of basal level MMTV transcription, even in the presence of multiple wild-type CDP- binding sites.

Effect of CDP-binding site mutations on basal and glucocorticoid-induced MMTV expression in XC fibroblasts.

Although our data have shown that CDP affects basal levels of MMTV expression, we could not determine CDP effects on hormone-inducible transcription because many normal mammary cell lines (including HC11 and NMuMG) have a minimal response to glucocorticoids (unpublished data). Thus, we determined whether CDP-mediated repression was demonstrable in XC rat cells, a line that shows good glucocorticoid induction of MMTV transcription (46).

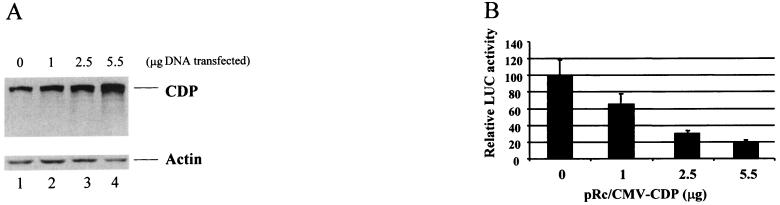

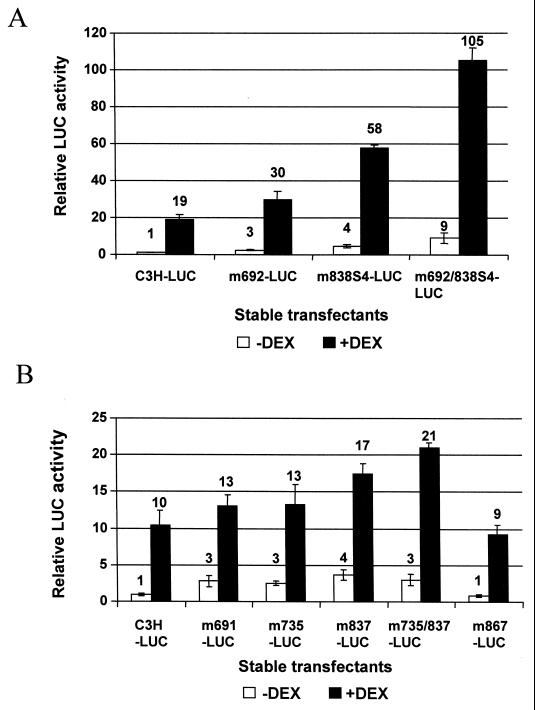

XC cells were cotransfected with various amounts of CDP expression vector or the empty vector and the MMTV LTR-reporter plasmid in transient assays (Fig. 7). Western blotting showed that XC cells have detectable CDP protein levels that were elevated 2.5-fold, as measured by densitometry, after transfection with CDP expression vectors (Fig. 7A). These experiments also showed that CDP overexpression repressed LTR-directed reporter activity up to fivefold, relative to cells that were transfected with the empty vector alone, in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7B). Subsequently, CDP overexpression experiments were repeated in the presence or absence of 10−6 M dexamethasone, a synthetic glucocorticoid hormone (Fig. 7C). These transfections showed that CDP suppressed expression from the wild-type MMTV LTR 5-fold in the presence of and 10-fold in the absence of hormone.

FIG. 7.

CDP overexpression suppresses MMTV LTR-reporter gene expression in XC cells. Rat fibroblast (XC) cells were transiently transfected using DMRIE-C with the reporter gene construct pC3H-LUC (1.5 μg) and increasing amounts of a CDP expression vector or a vector control lacking CDP sequences. Cytoplasmic extracts were prepared after 48 h. (A) Western blot analysis of XC cells after CDP overexpression. The cytoplasmic extract (30 μg of protein in each lane) was subjected to electrophoresis on an 8% polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and incubated with antiserum specific for CDP (top) or actin (bottom). (B) Relative luciferase activity of pC3H-LUC in the presence of increasing CDP concentrations. Cytoplasmic extract also was used for luciferase assays, and the results are expressed relative to the MMTV LTR activity in the absence of CDP overexpression (assigned a value of 100). Transfections were performed in triplicate for each experiment. Standard deviations from the means are indicated by error bars. (C) XC cells were transiently transfected with 0, 2, or 5.5 μg of CDP expression vectors (pRc/CMV-CDP) using DMRIE-C reagent in six-well plates. The total amount of DNA was kept constant using the cloning vector lacking CDP sequences. The wild-type C3H LTR-reporter plasmid pC3H-LUC (1.5 μg) was transfected as a reporter gene, and RL-TK (Promega) (100 ng) was cotransfected to normalize for DNA uptake. After 24 h, cells were treated with 10−6 M dexamethasone (DEX) and cultured for another 24 h prior to protein extractions. All luciferase activities are reported relative to that of pC3H-LUC in the absence of CDP overexpression and hormone treatment (assigned a luciferase activity of 1.0). The data shown represent three independent experiments, and transfections were performed in triplicate for each experiment. Standard deviations from the means are indicated by error bars.

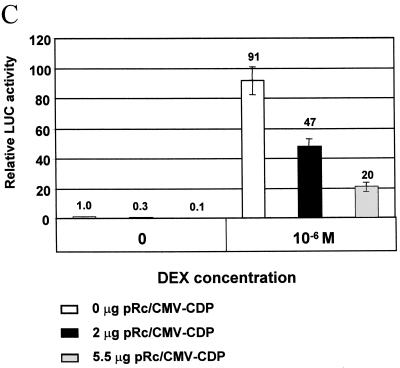

We also determined the effect of CDP-binding site mutations on the glucocorticoid responsiveness of the MMTV LTR (Fig. 8). XC cells were stably transfected with MMTV LTR-reporter gene constructs containing single CDP-binding site mutations. The wild-type MMTV LTR induced reporter gene activity 10- to 20-fold over the activity observed in the absence of hormone (Fig. 8). Such experiments revealed that single mutations in each of the tested CDP-binding sites (+837/838, +735, and +691/692) enhanced basal levels of MMTV expression, similar to results obtained in HC11 mammary cells, but also enhanced glucocorticoid-induced levels above those observed for the wild-type LTR reporter. Basal transcription increased ca. 4-fold in the +838 mutant over that seen with the wild-type LTR reporter plasmid, whereas the presence of glucocorticoids induced reporter activity 60-fold compared to basal wild-type activity. A combination of two mutations, one in the proximal NRE (+838) and one in the distal NRE (+692), showed approximately additive effects on basal transcription, whereas reporter gene activity of the double mutant was increased ca. 105-fold in the presence of hormone relative to basal wild-type activity (Fig. 8A). This additive effect was not detectable when the +735 mutation was combined with the +837 mutation. (However, effects of glucocorticoids were diminished in later experiments [Fig. 8B], presumably due to progressive loss of hormone receptors.) These experiments indicated that CDP suppresses MMTV expression both in the presence and absence of glucocorticoids.

FIG. 8.

Effect of CDP-binding site mutations on the response to glucocorticoids. XC cells were stably transfected LTR reporter gene constructs, pC3H-LUC (wild-type C3H MMTV LTR), or LTRs containing one or more CDP-binding-site mutations in the NREs. Cells were treated with 10−6 M DEX for 24 h prior to extractions for luciferase assays. Transfections shown in panels A and B were performed in different experiments. Results are reported relative to the wild-type C3H LTR reporter plasmid (pC3H-LUC) without DEX treatment in the same assay (assigned a value of 1). Error bars show standard deviations from the means.

DISCUSSION

Multiple CDP binding sites in the MMTV LTR.

Our previous experiments have shown that there are at least two NREs within the MMTV LTR U3 region (12, 30). The promoter-proximal NRE has two binding sites with different apparent affinities for the homeodomain-containing transcription factor, CDP (72). In this study, DNase I footprinting experiments suggested that there are five additional CDP-binding sites within the distal NRE. Four of these sites were confirmed by direct binding experiments with nonoverlapping oligonucleotides (Fig. 3). Moreover, software analysis indicated that there was a CDP-binding sequence between the proximal and distal NREs, and binding was confirmed by gel shift experiments (Fig. 4). This site appears to be different from another NRE identified in this region (32, 34). Therefore, we have detected at least seven CDP-binding sites in the MMTV LTR. An eighth site detected by DNase I footprinting (starting at +565) may be a weak site that requires the presence of high concentrations of CDP or cooperative binding with adjacent sites.

The presence of multiple CDP-binding sites is a common feature among promoters that are regulated by CDP. For example, the proximal promoter for the phagocyte cytochrome oxidase (phox) gene contains at least four binding sites for CDP (41), the immunoglobulin heavy chain intronic enhancer has six consensus sites (66, 67), and papilloma virus has at least three sites in the early promoter regulatory region (3, 49, 52). A common feature is that all of these viral and cellular genes, including those regulated by the MMTV LTR, are expressed in highly differentiated cell types. Although MMTV is expressed at low levels in a number of tissues, including kidney, lung, salivary gland, and reproductive and lymphoid organs, expression is at least 100-fold higher in the highly differentiated cells of the lactating mammary gland (15, 59). Several reports have indicated that CDP levels decline during differentiation of phagocytes, keratinocytes, and B cells (38, 52, 66, 67), and we recently have shown that CDP is regulated similarly in the mammary gland (72). High levels of CDP DNA-binding activity for the MMTV LTR are apparent in nuclear extracts of virgin mammary glands, whereas DNA-binding activity is undetectable in nuclear extracts of lactating glands (72). CDP has been shown to be a transcriptional repressor of MMTV and other promoters (4, 8, 13, 21, 37, 49, 60, 62, 64, 66, 72), suggesting that specialized gene products of terminally differentiated cells are expressed, in part, because of the lack of CDP DNA-binding activity.

Why are there so many CDP-binding sites within the MMTV LTR? One explanation is that CDP has a weak affinity for all binding sites in the LTR, and the presence of multiple binding sites is essential to promote cooperative binding for optimal repression of MMTV transcription in undifferentiated cells. Some of the binding sites, particularly those in the distal NRE, appear to be quite weak and were only observed in binding assays at high CDP concentrations. Each of the independent mutations that we have prepared (at least three different sites) elevates basal MMTV transcription. However, LTRs that combined two mutations (+692 and +838) gave approximately additive effects on relief of repression compared to each mutation alone, whereas another two mutations (+735 and +837) did not (Fig. 8). These results suggest that CDP binding to the MMTV LTR is not strictly cooperative and that different CDP-binding sites may use alternative mechanisms to induce repression.

MMTV is expressed in B cells, T cells, and mammary cells during viral transmission in mice (2, 20). Cell-type-specific transcription is likely to be controlled by the binding of positive factors to several different regulatory elements. We suggest that CDP binds to key positions in the LTR to block binding of positive regulatory factors essential for optimal MMTV expression in highly differentiated cells. Thus, in undifferentiated cells, MMTV RNA levels are suppressed. However, as CDP DNA-binding activity declines during differentiation, the presence of positive factors will determine the final level of transcription, depending on the affinity of CDP for the same site. On the other hand, it is possible that closely spaced CDP-binding sites (e.g., those in the distal NRE) (Fig. 2C) also act cooperatively to block the binding of transcriptional activators at specific points during mammary development.

CDP regulation of the glucocorticoid response.

Two pieces of evidence argue that CDP can modulate the transcriptional response of the MMTV LTR to at least one positive regulatory factor, GR. First, CDP can repress hormone-induced reporter gene expression from the MMTV promoter in XC cells (Fig. 7C). Second, mutation of CDP-binding sites in the MMTV LTR elevates glucocorticoid-induced reporter gene expression (Fig. 8). Together, these results indicate that CDP binding directly interferes with GR-mediated transcription from the MMTV promoter.

How does CDP affect GR function? Fletcher et al. (22) have previously shown that GR binds to at least six sites upstream of the MMTV transcriptional start site (Fig. 1). One of these sites (GRE5, starting at −274) maps to a position that contains a CDP-binding site in the promoter-proximal NRE (72). This site also overlaps with a strong binding site for the matrix-associated region binding protein, SATB1 (40). SATB1 DNA-binding activity for the MMTV LTR is not detectable in XC fibroblasts or mammary cells and, therefore, it is unlikely that SATB1 had an effect in the experiments performed here. Nevertheless, we have shown that increasing levels of CDP repress glucocorticoid-induced MMTV expression, a result that may be due to competition for binding of receptor to the GRE5 site. CDP initially was described as a factor that could repress transcription of the sperm histone H2B-1 gene by competition with the CCAAT-binding protein for binding to DNA (9).

GR also is believed to function in the remodeling of the nucleosomal structure 5" to the MMTV promoter prior to the binding of NF1 (14, 16). Like other genes, the MMTV promoter has a distinct nucleosomal arrangement that is believed to be responsible for general transcriptional repression (23, 55). Chromatin remodeling has been frequently associated with the recruitment of histone acetylases (HATs) followed by recruitment of factors that allow interaction with the basal transcription machinery (54, 65). In particular, GR and other members of the nuclear receptor family have been shown to interact with the LXXLL motif of the p160 family of coactivators (10, 24). The p160 proteins have intrinsic HAT activity, and they interact with other proteins, such as CBP (also called p300) that also have HAT function (10, 53). Both CBP and the p160 proteins have LXXLL motifs that can interact with the ligand-binding domain of nuclear receptors (10, 63). CDP has at least two LXXLL domains located between the N-terminal coiled-coil domain (64) and the first Cut repeat and, therefore, it is possible that CDP would function by competing with coactivators for binding to GR (i.e., by squelching) (25). Since the transcriptional repressor CDP has been shown to associate with histone deacetylases (HDACs) (37), the interaction between CDP and GR may neutralize any GR-recruited HAT activity.

Transcriptional suppression by CDP has been shown to occur simultaneously by competition for binding site occupancy as well as by “active repression” (42). It also has been reported that CDP interacts with CBP and p300/CBP-associated factors and that critical lysines near the C-terminal end of CDP can be modified by the HAT activity of PCAF, resulting in decreased CDP DNA-binding activity (36). Our preliminary data have shown that MMTV LTR-reporter gene expression was elevated sixfold in the presence of trichostatin A, an inhibitor of HDAC, compared to expression in the absence of the drug. On the other hand, reporter activities from MMTV LTRs containing CDP-binding site mutations were elevated only approximately twofold in the presence of trichostatin A, suggesting that less HDAC is recruited by mutant LTRs (data not shown). Thus, the ability of CDP to recruit HDAC appears to be affected by its DNA-binding activity, and DNA binding is affected by acetylation.

Data from this study clearly show that CDP can antagonize the transcriptional activation of the MMTV promoter mediated by glucocorticoids (Fig. 7 and 8). We also detected multiple CDP-binding sites upstream of the receptor-binding region in the MMTV LTR that may serve to interfere with the binding of other positive factors. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that CDP-binding activity for the MMTV LTR is downregulated in early stages of mammary development, suggesting that CDP may serve to repress the function of a number of transcriptional activators in the undifferentiated mammary gland. Thus, CDP may ensure maximal production of MMTV during lactation for efficient milk-borne transmission.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants R01 CA34780 and P01 CA77760 from the National Institutes of Health.

We are grateful to members of the Dudley laboratory and Keqin Gregg for helpful discussions and suggestions on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acha-Orbea, H. 1992. Retroviral superantigens. Chem. Immunol. 55:65-86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acha-Orbea, H. 1996. Mouse mammary tumor virus: the basics of an oncogenic retrovirus. Int. J. Cancer 66:285-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ai, W., E. Toussaint, and A. Roman. 1999. CCAAT displacement protein binds to and negatively regulates human papillomavirus type 6 E6, E7, and E1 promoters. J. Virol. 73:4220-4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andres, V., B. Nadal-Ginard, and V. Mahdavi. 1992. Clox, a mammalian homeobox gene related to Drosophila cut, encodes DNA-binding regulatory proteins differentially expressed during development. Development 116:321-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aufiero, B., E. J. Neufeld, and S. H. Orkin. 1994. Sequence-specific DNA binding of individual cut repeats of the human CCAAT displacement/cut homeodomain protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:7757-7761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ball, J. K., L. O. Arthur, and G. A. Dekaban. 1985. The involvement of a type-B retrovirus in the induction of thymic lymphomas. Virology 140:159-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ball, J. K., H. Diggelmann, G. A. Dekaban, G. F. Grossi, R. Semmler, P. A. Waight, and R. F. Fletcher. 1988. Alterations in the U3 region of the long terminal repeat of an infectious thymotropic type B retrovirus. J. Virol. 62:2985-2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banan, M., I. C. Rojas, W. H. Lee, H. L. King, J. V. Harriss, R. Kobayashi, C. F. Webb, and P. D. Gottlieb. 1997. Interaction of the nuclear matrix-associated region (MAR)-binding proteins, SATB1 and CDP/Cux, with a MAR element (L2a) in an upstream regulatory region of the mouse CD8α gene. J. Biol. Chem. 272:18440-18452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barberis, A., G. Superti-Furga, and M. Busslinger. 1987. Mutually exclusive interaction of the CCAAT-binding factor and of a displacement protein with overlapping sequences of a histone gene promoter. Cell 50:347-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bevan, C., and M. Parker. 1999. The role of coactivators in steroid hormone action. Exp. Cell Res. 253:349-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blochlinger, K., R. Bodmer, J. Jack, L. Y. Jan, and Y. N. Jan. 1988. Primary structure and expression of a product from cut, a locus involved in specifying sensory organ identity in Drosophila. Nature 333:629-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bramblett, D., C. L. Hsu, M. Lozano, K. Earnest, C. Fabritius, and J. Dudley. 1995. A redundant nuclear protein binding site contributes to negative regulation of the mouse mammary tumor virus long terminal repeat. J. Virol. 69:7868-7876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chattopadhyay, S., C. E. Whitehurst, and J. Chen. 1998. A nuclear matrix attachment region upstream of the T cell receptor beta gene enhancer binds Cux/CDP and SATB1 and modulates enhancer-dependent reporter gene expression but not endogenous gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 273:29838-29846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chavez, S., and M. Beato. 1997. Nucleosome-mediated synergism between transcription factors on the mouse mammary tumor virus promoter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:2885-2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi, Y. W., D. Henrard, I. Lee, and S. R. Ross. 1987. The mouse mammary tumor virus long terminal repeat directs expression in epithelial and lymphoid cells of different tissues in transgenic mice. J. Virol. 61:3013-3019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cordingley, M. G., A. T. Riegel, and G. L. Hager. 1987. Steroid-dependent interaction of transcription factors with the inducible promoter of mouse mammary tumor virus in vivo. Cell 48:261-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dickinson, L. A., T. Joh, Y. Kohwi, and T. Kohwi-Shigematsu. 1992. A tissue-specific MAR/SAR DNA-binding protein with unusual binding site recognition. Cell 70:631-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dignam, J. D., P. L. Martin, B. S. Shastry, and R. G. Roeder. 1983. Eukaryotic gene transcription with purified components. Methods Enzymol. 101:582-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dudley, J., and R. Risser. 1984. Amplification and novel locations of endogenous mouse mammary tumor virus genomes in mouse T-cell lymphomas. J. Virol. 49:92-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dudley, J. P. 1999. Mouse mammary tumor virus, p. 965-972. In R. G. Webster and A. Granoff (ed.), Encyclopedia of virology. Academic Press Ltd., London, United Kingdom.

- 21.Dufort, D., and A. Nepveu. 1994. The human cut homeodomain protein represses transcription from the c -myc promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:4251-4257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fletcher, T. M., B. W. Ryu, C. T. Baumann, B. S. Warren, G. Fragoso, S. John, and G. L. Hager. 2000. Structure and dynamic properties of a glucocorticoid receptor-induced chromatin transition. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:6466-6475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fragoso, G., S. John, M. S. Roberts, and G. L. Hager. 1995. Nucleosome positioning on the MMTV LTR results from the frequency-biased occupancy of multiple frames. Genes Dev. 9:1933-1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freedman, L. P. 1999. Strategies for transcriptional activation by steroid/nuclear receptors. J. Cell. Biochem. Suppl. 32-33:103-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gill, G., and M. Ptashne. 1988. Negative effect of the transcriptional activator GAL4. Nature 334:721-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Golovkina, T. V., J. P. Dudley, and S. R. Ross. 1998. B and T cells are required for mouse mammary tumor virus spread within the mammary gland. J. Immunol. 161:2375-2382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henrard, D., and S. R. Ross. 1988. Endogenous mouse mammary tumor virus is expressed in several organs in addition to the lactating mammary gland. J. Virol. 62:3046-3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herman, A., J. W. Kappler, P. Marrack, and A. M. Pullen. 1991. Superantigens: mechanism of T-cell stimulation and role in immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 9:745-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higuchi, R. 1990. Recombinant PCR, p. 177-183. In M. A. Innis, D. H. Gelfand, J. J. Sninsky, and T. J. White (ed.), PCR protocols, a guide to methods and applications. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, Calif.

- 30.Hsu, C. L., C. Fabritius, and J. Dudley. 1988. Mouse mammary tumor virus proviruses in T-cell lymphomas lack a negative regulatory element in the long terminal repeat. J. Virol. 62:4644-4652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janeway, C. A., Jr. 1991. Selective elements for the Vβ region of the T cell receptor: Mls and the bacterial toxic mitogens. Adv. Immunol. 50:1-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang, C. J., and D. O. Peterson. 1999. Identification of a protein that recognizes a distal negative regulatory element within the mouse mammary tumor virus long terminal repeat. Virology 264:211-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lavallie, E. R., J. M. McCoy, D. B. Smith, and P. Riggs. 1994. Enzymatic and chemical cleavage of fusion proteins, p. 16.4.5-16.4.17. In F. M. Ausubel, R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.), Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Lee, J. W., P. G. Moffitt, K. L. Morley, and D. O. Peterson. 1991. Multipartite structure of a negative regulatory element associated with a steroid hormone-inducible promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 266:24101-24108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee, W. T., O. Prakash, D. Klein, and N. H. Sarkar. 1987. Structural alterations in the long terminal repeat of an acquired mouse mammary tumor virus provirus in a T-cell leukemia of DBA/2 mice. Virology 159:39-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li, S., B. Aufiero, R. L. Schiltz, and M. J. Walsh. 2000. Regulation of the homeodomain CCAAT displacement/cut protein function by histone acetyltransferases p300/CREB-binding protein (CBP)-associated factor and CBP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:7166-7171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li, S., L. Moy, N. Pittman, G. Shue, B. Aufiero, E. J. Neufeld, N. S. LeLeiko, and M. J. Walsh. 1999. Transcriptional repression of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene, mediated by CCAAT displacement protein/cut homolog, is associated with histone deacetylation. J. Biol. Chem. 274:7803-7815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lievens, P. M., J. J. Donady, C. Tufarelli, and E. J. Neufeld. 1995. Repressor activity of CCAAT displacement protein in HL-60 myeloid leukemia cells. J. Biol. Chem. 270:12745-12750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu, J., A. Barnett, E. J. Neufeld, and J. P. Dudley. 1999. Homeoproteins CDP and SATB1 interact: potential for tissue-specific regulation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:4918-4926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu, J., D. Bramblett, Q. Zhu, M. Lozano, R. Kobayashi, S. R. Ross, and J. P. Dudley. 1997. The matrix attachment region-binding protein SATB1 participates in negative regulation of tissue-specific gene expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:5275-5287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luo, W., and D. G. Skalnik. 1996. CCAAT displacement protein competes with multiple transcriptional activators for binding to four sites in the proximal gp91 phox promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 271:18203-18210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mailly, F., G. Berube, R. Harada, P. L. Mao, S. Phillips, and A. Nepveu. 1996. The human cut homeodomain protein can repress gene expression by two distinct mechanisms: active repression and competition for binding site occupancy. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:5346-5357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Majors, J., and H. E. Varmus. 1983. A small region of the mouse mammary tumor virus long terminal repeat confers glucocorticoid hormone regulation on a linked heterologous gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80:5866-5870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Majors, J. E., and H. E. Varmus. 1983. Nucleotide sequencing of an apparent proviral copy of env mRNA defines determinants of expression of the mouse mammary tumor virus env gene. J. Virol. 47:495-504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marrack, P., G. M. Winslow, Y. Choi, M. Scherer, A. Pullen, J. White, and J. W. Kappler. 1993. The bacterial and mouse mammary tumor virus superantigens; two different families of proteins with the same functions. Immunol. Rev. 131:79-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mertz, J. A., F. Mustafa, S. Meyers, and J. P. Dudley. 2001. Type B leukemogenic virus has a T-cell-specific enhancer that binds AML-1. J. Virol. 75:2174-2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Michalides, R., and E. Wagenaar. 1986. Site-specific rearrangements in the long terminal repeat of extra mouse mammary tumor proviruses in murine T-cell leukemias. Virology 154:76-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Michalides, R., E. Wagenaar, J. Hilkens, J. Hilgers, B. Groner, and N. E. Hynes. 1982. Acquisition of proviral DNA of mouse mammary tumor virus in thymic leukemia cells from GR mice. J. Virol. 43:819-829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O'Connor, M. J., W. Stunkel, C. H. Koh, H. Zimmermann, and H. U. Bernard. 2000. The differentiation-specific factor CDP/Cut represses transcription and replication of human papillomaviruses through a conserved silencing element. J. Virol. 74:401-410. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Olnes, M. I., and R. N. Kurl. 1994. Isolation of nuclear extracts from fragile cells: a simplified procedure applied to thymocytes. BioTechniques 17:828-829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parks, W. P., J. C. Ransom, H. A. Young, and E. M. Scolnick. 1975. Mammary tumor virus induction by glucocorticoids. Characterization of specific transcriptional regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 250:3330-3336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pattison, S., D. G. Skalnik, and A. Roman. 1997. CCAAT displacement protein, a regulator of differentiation-specific gene expression, binds a negative regulatory element within the 5" end of the human papillomavirus type 6 long control region. J. Virol. 71:2013-2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perissi, V., J. S. Dasen, R. Kurokawa, Z. Wang, E. Korzus, D. W. Rose, C. K. Glass, and M. G. Rosenfeld. 1999. Factor-specific modulation of CREB-binding protein acetyltransferase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:3652-3657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peterson, C. L., and C. Logie. 2000. Recruitment of chromatin remodeling machines. J. Cell. Biochem. 78:179-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Richard-Foy, H., and G. L. Hager. 1987. Sequence-specific positioning of nucleosomes over the steroid-inducible MMTV promoter. EMBO J. 6:2321-2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ringold, G. M., K. R. Yamamoto, J. M. Bishop, and H. E. Varmus. 1977. Glucocorticoid-stimulated accumulation of mouse mammary tumor virus RNA: increased rate of synthesis of viral RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:2879-2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rosen, J. M., S. L. Wyszomierski, and D. Hadsell. 1999. Regulation of milk protein gene expression. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 19:407-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ross, S. R. 1998. Mouse mammary tumor virus and its interaction with the immune system. Immunol. Res. 17:209-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ross, S. R., C. L. Hsu, Y. Choi, E. Mok, and J. P. Dudley. 1990. Negative regulation in correct tissue-specific expression of mouse mammary tumor virus in transgenic mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:5822-5829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Skalnik, D. G., E. C. Strauss, and S. H. Orkin. 1991. CCAAT displacement protein as a repressor of the myelomonocytic-specific gp91-phox gene promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 266:16736-16744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith, D. B. 1993. Purification of glutathione-S-transferase fusion proteins. Methods Mol. Cell. Biol. 4:220-229. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Superti-Furga, G., A. Barberis, G. Schaffner, and M. Busslinger. 1988. The −117 mutation in Greek HPFH affects the binding of three nuclear factors to the CCAAT region of the γ-globin gene. EMBO J. 7:3099-3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Torchia, J., D. W. Rose, J. Inostroza, Y. Kamei, S. Westin, C. K. Glass, and M. G. Rosenfeld. 1997. The transcriptional co-activator p/CIP binds CBP and mediates nuclear-receptor function. Nature 387:677-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Valarche, I., J. P. Tissier-Seta, M. R. Hirsch, S. Martinez, C. Goridis, and J. F. Brunet. 1993. The mouse homeodomain protein Phox2 regulates Ncam promoter activity in concert with Cux/CDP and is a putative determinant of neurotransmitter phenotype. Development 119:881-896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wallberg, A. E., K. E. Neely, J. A. Gustafsson, J. L. Workman, A. P. Wright, and P. A. Grant. 1999. Histone acetyltransferase complexes can mediate transcriptional activation by the major glucocorticoid receptor activation domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:5952-5959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang, Z., A. Goldstein, R. T. Zong, D. Lin, E. J. Neufeld, R. H. Scheuermann, and P. W. Tucker. 1999. Cux/CDP homeoprotein is a component of NF-μNR and represses the immunoglobulin heavy chain intronic enhancer by antagonizing the bright transcription activator. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:284-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Webb, C., R.-T. Zong, D. Lin, Z. Wang, M. Kaplan, Y. Paulin, E. Smith, L. Probst, J. Bryant, A. Goldstein. R. Scheuermann, and P. Tucker. 1999. Differential regulation of immunoglobulin gene transcription via nuclear matrix-associated regions. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 64:109-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wingender, E., X. Chen, R. Hehl, H. Karas, I. Liebich, V. Matys, T. Meinhardt, M. Pruss, I. Reuter, and F. Schacherer. 2000. TRANSFAC: an integrated system for gene expression regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:316-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wrona, T. J., M. Lozano, A. A. Binhazim, and J. P. Dudley. 1998. Mutational and functional analysis of the C-terminal region of the C3H mouse mammary tumor virus superantigen. J. Virol. 72:4746-4755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xu, L., T. J. Wrona, and J. P. Dudley. 1996. Exogenous mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) infection induces endogenous MMTV sag expression. Virology 215:113-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xu, L., T. J. Wrona, and J. P. Dudley. 1997. Strain-specific expression of spliced MMTV RNAs containing the superantigen gene. Virology 236:54-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhu, Q., K. Gregg, M. Lozano, J. Liu, and J. P. Dudley. 2000. CDP is a repressor of mouse mammary tumor virus expression in the mammary gland. J. Virol. 74:6348-6357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]