Abstract

Background:

The surgical management of Hirschsprung's disease (HD) has evolved from the original 3-stage approach to the recent introduction of minimal-access single-stage techniques. We reviewed the early results of the transanal Soave pullthrough from 6 of the original centers to use it.

Methods:

The clinical course of all children with HD undergoing a 1-stage transanal Soave pullthrough between 1995 and 2002 were reviewed. Children with a preliminary stoma or total colonic disease were excluded.

Results:

There were 141 patients. Mean time between diagnosis and surgery was 32 days, and mean age at surgery was 146 days. Sixty-six (47%) underwent surgery in the first month of life. Forty-seven (33%) had the pathologic transition zone documented laparoscopically or through a small umbilical incision before beginning the anal dissection. Mean blood loss was 16 mL, and no patients required transfusion. Mean time to full feeding was 36 hours, mean postoperative hospital stay was 3.4 days, and 87 patients (62%) required only acetaminophen for pain. Early postoperative complications included perianal excoriation (11%), enterocolitis (6%), and stricture (4%). One patient died of congenital cardiac disease. Mean follow-up was 20 months; 81% had normal bowel function for age, 18% had minor problems, and 1% had major problems. Two patients required a second operation (twisted pullthrough, and residual aganglionosis). One patient developed postoperative adhesive bowel obstruction.

Conclusion:

To date, this report represents the largest series of patients undergoing the 1-stage transanal Soave pullthrough. This approach is safe, permits early feeding, causes minimal pain, facilitates early discharge, and presents a low rate of complications.

One-hundred forty-one children with Hirschsprung disease underwent a transanal Soave pullthrough at 6 pediatric surgical centers. Complication rates were comparable to that reported for the open Soave procedure, but the transanal approach was associated with a short hospital stay, minimal pain, and absence of a visible abdominal scar.

Hirschsprung disease is a congenital disorder characterized by the absence of ganglion cells in the distal bowel, which results in functional obstruction, most commonly in the newborn period. Traditionally, surgical therapy for Hirschsprung disease has consisted of a proximal defunctioning colostomy, followed months later by a definitive reconstructive “pullthrough” procedure in which the aganglionic colon is resected and the normally innervated bowel is brought down and sutured to the area just above the anal sphincter. Although many types of pullthrough procedures have been described, the most commonly performed operations in North America have been the Swenson, Duhamel, and Soave (or endorectal pullthrough) procedures. In the past several decades, increasing numbers of pediatric surgeons have abandoned the routine use of a colostomy in favor of a 1-stage pullthrough, with multiple studies suggesting that this approach is safe and efficacious.1-3

Over the past few years, the popularity of minimal-access surgical techniques has led to a number of modifications to the standard 1-stage operations. Georgeson described a laparoscopic approach that has been adopted by many surgeons and that is associated with less pain and a shorter hospitalization than standard open procedures.4 Subsequently, a number of authors described a solely transanal approach, which appears to be associated with the same advantages without the need for any intraabdominal dissection.5-9 However, the results from this approach have been limited to single-center or small multicenter series with relatively short follow-up.10-14 The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the early results of the transanal Soave pullthrough. To optimize the number of patients and the length of follow-up, we combined data from 6 of the initial centers to perform the procedure.

METHODS

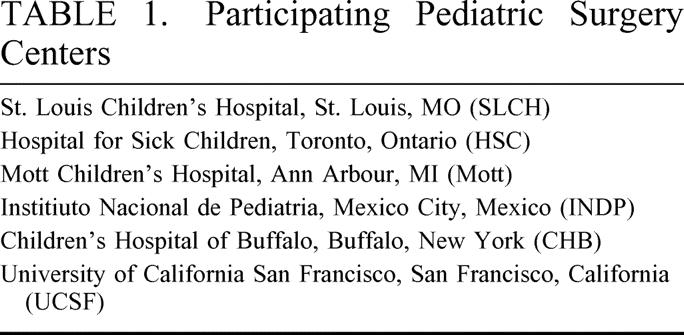

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of all children who had a 1-stage transanal Soave pullthrough procedure for the repair of Hirschsprung's disease between 1995 and 2002 in 6 North American pediatric surgery centers (Table 1). The study was approved by each institution's Ethics Review Board. Patients with a previous colostomy, those with total colonic disease, and those who had undergone surgery at another center were excluded. The following data were collected: sex, gestational age at birth, birth weight, age at diagnosis, clinical presentation, level of aganglionosis, preoperative management, operative technique, intraoperative complications, time to full oral feeding, use of narcotics, early (within 30 days) and late postoperative complications and follow-up data, including complications, ongoing requirements for oral gastrointestinal medications, and effectiveness of potty training.

TABLE 1. Participating Pediatric Surgery Centers

The technique used was basically the same in each center, although minor variations were present between centers and over time at individual centers. The mucosa was incised circumferentially just above the dentate line and a submucosal dissection was carried proximally. The muscle was then incised circumferentially and the dissection carried proximally along the outer wall of the rectal muscle. When the transition zone was reached, a biopsy was conducted to confirm ganglion cells by frozen section. In some cases the pathologic transition zone was identified laparoscopically or through a small umbilical incision before beginning the anal dissection. The bowel was then transected and an anastomosis was performed. In most cases the muscular rectal cuff was divided before performing the anastomosis. Results were expressed as the mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using either a paired or an unpaired t test or χ2 analysis, with a P value less than 0.05 being considered significant.

RESULTS

One-hundred forty-one neonates, infants, and children were included in the study analysis. There were 113 boys (80.1%) and 28 girls (19.9%). Four children had Trisomy 21, 3 had major cardiac defects, and 1 child had congenital central hypoventilation syndrome. None of the other children had significant associated abnormalities. The average gestational age at birth was 39 ± 0.78 weeks, with a mean birth weight of 3.27 ± 0.19 kg. The age at diagnosis was 30 days or less in 84 children (59.6%), 1 month to 1 year in 24 (17%), and greater than 1 year in 15 (10.6%), with the mean age at diagnosis being 108.5 ± 100.2 days (range, 1 day to 12 years). There was no significant difference between participating centers regarding gender differences. However, the mean birth weight of the children enrolled in the study from INDP was statistically smaller than the group average (P < 0.05), and the mean age at diagnosis was significantly younger than the group average for SLCH and CHB (11.5 and 20.7, P < 0.05).

Clinical presentation included neonatal bowel obstruction in 85 cases (60.3%), constipation in 69 cases (48.9%) and enterocolitis in 20 cases (14.2%); some children had more than 1 presenting symptom. Of the 117 children in whom the contrast study was available for review, the radiologic transition zone was in the rectum or rectosigmoid in 80 cases (68.4%), the more proximal colon in 5 cases (4.3%), and did not demonstrate a transition zone in 32 cases (27.3%). To confirm the diagnosis, patients underwent rectal biopsy using a suction technique in 83 cases, full thickness in 34 cases, or punch biopsy in 1 case; the technique was not reported in the other cases.

Preoperatively, 129 children received some form of bowel preparation, including digital rectal stimulations (18%), bowel irrigations (54%) or a combination of both (28%). Nutrition was maintained with breast milk (47%), elemental feeds (14%), or regular formula (39%).

The mean time from diagnosis to definitive surgery was 31.9 ± 19.8 days (range, 0 to 300 days). Mean age at the time of surgery was 145.9 ± 81.1 day (range, 1 to 4380 days), and 66 of the children (46.8%) were within the first 30 days of life. Children at HSC and CHB were significantly younger than the group mean (56.7 and 87.7 days of life, P < 0.05). Mean weight at the time of surgery was 5.47 ± 0.77 kg (range, 2.6 to 33.18 kg), and was significantly lower than the group mean only for HSC (4.3 kg, P < 0.05).

The average operating time was 204.4 ± 38.2 minutes, (range, 60 to 490 minutes). Mean intraoperative blood loss was estimated to be 14.5 ± 12.1 mL. No patient required a blood transfusion. The pathologic transition zone was confined to the rectosigmoid in 77% of the children, and was in the more proximal colon in the other 23%. There was a discrepancy between the radiologic and pathologic transition zone in 5 cases; in 3 the pathologic transition zone was more proximal than the radiologic transition zone, and in 2 it was more distal. In the 32 cases where no transition zone was seen on barium enema, the pathologic transition zone was found at the splenic flexure in two, rectosigmoid in 24, and rectum in 6.

In 47 cases, the pathologic transition zone was identified before initiating the anal dissection. This was performed laparoscopically in 16 and using a small umbilical incision in 31. The decision was based on surgeon preference. Nine cases were converted to an open procedure to mobilize the splenic flexure in longer segment disease. None of the patients required the formation of a colostomy.

Intraoperative complications were reported in 4 cases. One child developed cardiac tamponade secondary to an internal jugular line during the colon biopsy prior to beginning the anal dissection. She came back to the operating room and had an uneventful transanal Soave done several weeks later. Two cases required refashioning of the anastomosis because of tearing or tissue friability. One patient had an intraoperative injury to the left vas deferens.

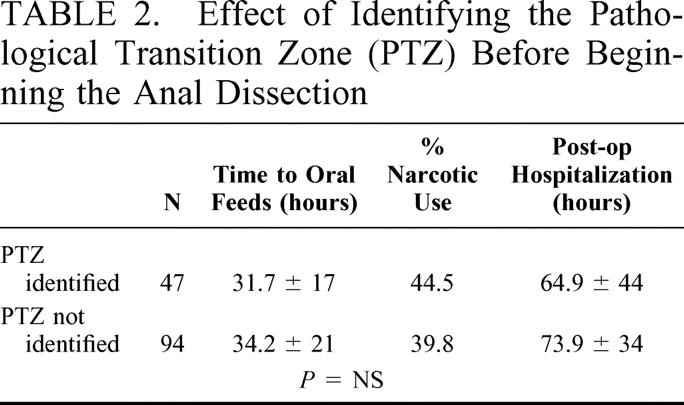

Postoperatively, the mean time to oral feeding was 36 ± 19.3 hours (range, 2–216 hours). A significant difference from the group average was noted for SLCH, HSC, and CHB (19.1, 14.8 and 22.9 hours, P < 0.05). Sixty-three patients (44.7%) had a caudal block before or at the end of the operation. Only 55 patients (39%) received narcotics, with the average duration of consumption being less than 24 hours (range, 0.95 ± 1.1 day). No patients were discharged home on narcotic analgesics. Narcotic use was significantly shorter at SLCH, CHB, and INDP (0.03, 0.46, and 0 days, P < 0.05. Mean postoperative hospital stay was 81.3 ± 30.8 hours and was significantly shorter at SLCH and CHB (38.9 and 52.5 hours, P < 0.05). When the patients undergoing preliminary identification of the pathologic transition zone using a laparoscopic or umbilical approach were compared with those having a straight transanal approach, no significant differences in postoperative feeding, narcotic use, or hospital stay were found (Table 2).

TABLE 2. Effect of Identifying the Pathological Transition Zone (PTZ) Before Beginning the Anal Dissection

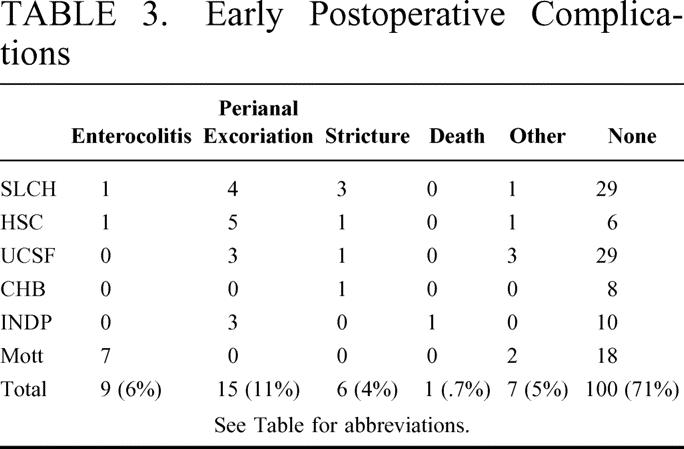

Early postoperative complications occurred in 38 patients (27%) and are summarized in Table 3. There was no significant difference in early postoperative complication rates among centers. Postoperative enterocolitis developed in 9 children, of which only 1 patient had a preoperative history of enterocolitis. Significant perianal excoriation and stricture occurred uncommonly, and no patient had a postoperative anastomotic leak. One death occurred in the early postoperative period secondary to the patient's associated cardiac abnormality. This child had normal stools with no gastrointestinal problems before his death, and there was no evidence of gastrointestinal pathology on autopsy.

TABLE 3. Early Postoperative Complications

Twenty-three patients were lost to follow-up. Mean length of follow-up in the remaining 118 children was 20.2 ± 9.2 months. Of these, 95 (80.5%) were reported by their parents and caregivers as having normal bowel function, 21 had ongoing minor problems such as loose stools, mild-to-moderate constipation, or perianal excoriation, and 2 had ongoing major problems (severe vomiting in 1 child and persistent severe constipation in another). Eleven patients were taking chronic medication for their intestinal problems, including stool softeners, enemas, or antibiotics. At the time of follow-up only 13 patients had been successfully potty trained, at an average of 15.3 ±16.2 months of age.

Four patients required additional surgery. Two had narrowing of the muscular rectal cuff resulting in obstructive symptoms (one of whom also had a twisted pullthrough). Both were managed by repeat Soave pullthrough within a month of the transanal pullthrough using an open technique. One child had residual aganglionosis that required a second pullthrough using the Duhamel technique15 6 months after the transanal procedure. The fourth patient developed a bowel obstruction and required adhesiolysis. Two late deaths were reported, both of which were unrelated to the patient's surgery. One died of respiratory failure secondary to congenital central hypoventilation syndrome, and the second died of congenital cardiac disease.

DISCUSSION

The transanal Soave pullthrough is essentially the same operation that has been performed open for decades, but it avoids the need for a laparotomy and intraabdominal mobilization of the rectum. For this reason it theoretically should not be associated with a higher complication or failure rate. Because the anal dissection is above the anoderm, and therefore no somatic pain fibers are cut, the operation should not be accompanied by pain. The lack of intraabdominal dissection should result in a shorter time to feeds and to discharge and possibly a lower incidence of intraabdominal adhesion formation, and the lack of large abdominal incisions should produce a superior cosmetic result. Our data suggest that these theoretical assumptions are in fact true, since our rate of complications was similar or lower than those reported in the literature for the open Soave procedure, and at the same time our patients benefited from minimal pain, a short time to feeding and discharge, and a scarless or nearly scarless abdomen. This was true whether or not a laparoscopic or umbilical incision biopsy to identify the transition zone was done. In comparison to the laparoscopic pullthrough described by Georgeson,4 the transanal approach may be superior because it avoids the need for intraabdominal mobilization of the rectum, and it can be performed by any experienced pediatric surgeon, even one who is not skilled in laparoscopic surgery.

This study suffers from some of the weaknesses of a multicenter study. The technique used, although similar, was not identical in each center, and the patient populations and patient care routines may have been variable among centers. The outcome measures may also have been interpreted differently from one center to another. However, these weaknesses are compensated for by the benefits of having created the largest series to date undergoing this procedure, with the longest follow-up reported so far. The data clearly suggest the safety and efficacy of this operation in the hands of a variety of surgeons and centers.

There was a wide range of ages at diagnosis, and a range of times between the diagnosis and the pullthrough in our series. Although we did not have an accurate way of quantifying the effect of proximal colonic dilatation, it is clear that this approach can be used even in children presenting beyond the neonatal period. It is possible in many cases to reduce the size of the distended colon using colonic irrigations, and to avoid the need for a colostomy. There was no discernable difference in outcome between those presenting early and those presenting later.

There have also been a number of ongoing changes in technique as each surgeon has learned from his/her experience. There has been a tendency to make the submucosal dissection shorter, and to always divide the muscular cuff to avoid the cuff narrowing seen in some of the early patients. Many surgeons visualized the anal dissection laparoscopically, but stopped doing this once they felt more comfortable with the dissection.6 Various types of anal retractors, cautery techniques, and suture materials have been used.

One controversy which continues to be pertinent is whether the transanal dissection should be initiated before confirming the location of the pathologic transition zone. This decision is particularly important for those surgeons who believe that the Soave pullthrough is not optimal for patients with long-segment disease in the proximal colon, who might be better served with a Duhamel or colon patch procedure.16 It is being increasingly recognized that the preoperative contrast study is inaccurate in a small proportion of infants; a recent series demonstrated that 8% of infants with a radiologic transition zone in the rectosigmoid had a pathologic transition zone that was significantly more proximal.17 Thus, many surgeons believe that the transition zone should be confirmed using laparoscopy or a small umbilical incision prior to beginning the anal dissection.18 Our data suggest that the use of a preliminary biopsy does not diminish the benefits of the transanal approach.

In summary, our data suggest that the transanal Soave procedure offers an improved approach to the child with Hirschsprung disease, and may be used by any experienced pediatric surgeon. Further studies documenting the long term results of this approach, particularly with respect to continence and stool frequency, will be needed as these children grow and develop.

Discussion

Dr. Orvar Swenson (Charleston, South Carolina): I rise to commend the authors for exploring a different surgical approach for treating Hirschsprung’s disease. I have had little experience with this. We have used a combined abdominal transanal approach in resecting impermeable strictures, and it has worked very well.

Over one-half century ago, our investigations convinced us that the distal segment of colon in this disease contained a physiological obstruction, and we have tested our hypothesis by resecting all the obstructive segment in a sick child. Here is a picture of the patient 55 years later. He has normal intestinal function, has served in the United States Navy, is married and has 3 children.

The problem with the Soave modification, which was used in this presentation, is that it leaves a considerable amount of obstructive tissue in place and makes a peculiar telescoping anastomosis that leads to considerable obstruction according to Kimura and others who have shown that it increases the anal canal resistance to a point where severe constipation may follow and may require additional surgery.

Now, it is perfectly true that with this Soave modification you can have immediate good results. However, if you follow these patients for a period of 15 or 20 years, as Fortuna and others have done, they have found that one-quarter of the patients require laxatives, collates, or enemas to maintain intestinal function. More disturbing, Tariq and others have found that the problem of distension and constipation increase with time in patients treated with the Soave.

Sherman, in 1986 reported a study of 880 patients followed for 40 years. And in that group, all the defective tissue was removed, 96% had normal intestinal function and did not require laxatives of any kind. Furthermore, there were no reports of urinary or sexual dysfunction. That study has been corroborated by Puri and Nixon, Nielson and Maxen, and more recently by Madonna and Luck.

I would like to ask, Dr. Langer, what does a patient gain by having obstructive lesion left in place which studies have shown in the long run prevents a patient from having complete relief of their symptoms? Waldhausen, using the transanal approach, removes all the obstructive, muscular coat as well as the mucosa and makes a simple end-to end anastomosis. I know ease of performing an operation should be given some consideration, but from the patient’s point of view, long-term end results are of paramount importance. Thank you.

Dr. Jacob C. Langer (Toronto, Ontario, Canada): First of all, I just want to say it is a great honor for me to have Dr. Swenson comment on this paper. It humbles me to recognize the work that he did and the contributions that he made in the management of Hirschsprung’s disease.

I would answer the question by saying that the evolution of this transanal Soave procedure has involved shortening the remaining muscles that we leave behind.

Most of us started by doing our submucosal dissection all the way up above the peritoneal reflection just so that we knew for sure that we weren’t going to hurt anything doing it blindly from below. As we became more comfortable with the operation, we began shortening that more and more. Now my practice is to go up only 2 or 3 cm so that we are leaving a very, very short rectal cuff. And largely the reason for that was because of Dr. Swenson’s point, that we don’t want to leave any more of that aganglionic rectal muscle behind than we have to.

Also, I think it would be interesting for Dr. Swenson to know that a number of groups have actually shortened the rectal cuff right down to just above the dentate line and are in fact doing a transanal Swenson operation. The group in Hamilton, Ontario has been doing that for a number of years and there several other groups now that are beginning to report this. So I think the difference between a Swenson and a Soave is starting to blur a little bit as we use shorter and shorter cuffs.

The final thing is that for many of the patients who have ongoing obstructive symptoms and ongoing constipation, it is not because of the rectal cuff that is left behind, it is because the anal sphincter in patients with Hirschsprung’s disease does not relax. It is part of the disease that they are lacking their recto-anal inhibitory reflex. I think that is the reason that many of them have ongoing constipation. And despite the excellent results that have been reported with the Swenson operation, there are still a group of patients who have had a Swenson who do have ongoing obstructive symptoms.

I just want to thank Dr. Swenson again for his comments.

Dr. George W. Holcomb, iii (Kansas City, Missouri): It is obviously very difficult to add any significant comments to Dr. Swenson’s thoughts. But I do appreciate the opportunity to comment on this paper and certainly congratulate the authors on their results.

The authors have shown many advantages that occur with the primary pullthrough technique for correction of Hirschsprung’s disease including reduced postoperative hospitalization, early initiation of feedings, a marked diminution in the need for narcotics, and the lack of a colostomy. And these same advantages have been seen with the laparoscopic pullthrough as well.

The major problem that I am concerned about this technique is perhaps – and I underline the word ‘perhaps‘ – undue tension on the pullthrough colon and potential vascular compromise if the root of the rectosigmoid mesentery is not mobilized from above. As you know, Dr. Keith Georgeson described the laparoscopic pullthrough in the mid 1990s. In his multicenter series, which he reported in the late 1990s, the mean operating time for his operation was 149 minutes compared with 202 minutes in your series. I wonder if the shorter operating time that he reported may be a reflection of mobilizing the rectosigmoid colon from above which may allow for an easier transanal dissection. Would you comment on that?

There are 3 other questions that I have.

The first is that the mean time between diagnosis and operative correction was 32 days. I question why that delay was so long. In my experience, we usually wait 3 to 7 days to clean out the colon and prepare the patient for a primary pullthrough. I wish you would comment on why the delay was approximately 1 month.

Next, there was no transition zone seen on the barium enema in 27% of the patients in the manuscript. In my mind, if I don’t see a transition zone, I worry that the patient may not be an appropriate candidate for a primary pullthrough. I wonder how many of these patients without a transition zone on a barium enema actually have long segment disease and required something else such as open or laparoscopic colonic mobilization or perhaps even an initial ostomy.

Finally, is a patient presenting initially with enterocolitis – and we seem to be seeing a lot more of these patients in the last few years – still a reasonable candidate for a primary pullthrough procedure? If so, how long do you treat that patient with antibiotics prior to performing the primary pullthrough procedure? Some pediatric surgeons feel that these children may be better served with an initial colostomy to allow the enterocolitis to ‘cool down.‘ Would you comment on this problem?

Again, thank you very much for the opportunity to discuss your paper.

Dr. Jacob C. Langer (Toronto, Ontario, Canada): I appreciate your comments.

The first point that you made had to do with the potential for tension on the anastomosis if you haven’t mobilized the colonic mesentery. It was actually very surprising to me how seldom we have had a problem with tension. If you look at the results, we have a very low rate of stricture. And usually tension causes stricture.

I think once you get up into the proximal sigmoid colon you cannot do a transanal pullthrough safely without mobilizing the mesentery and/or mobilizing the splenic flexure. And in those patients we did have to do something either laparoscopically or through an incision. We had 9 patients in which that was the case. That answers, I think, your third question, which was how often did we find longer segment disease than we expected and have to open. Most of the time I find that you can do that mobilization either laparoscopically or through that small umbilical incision that I showed you, which doesn’t result in any prolongation of their hospital stay or their time to full feeds.

You asked about the one-month gap between the diagnosis and the pullthrough. That was actually quite variable among the centers. I think there is still a lot of variability in practice. I didn’t have time to go into the details of the variability, but many of the things I showed you in terms of the way the operation is done are different from 1 center to another.

There are some surgeons who feel a little more comfortable doing the operation on a child who is a little bit bigger, and that was probably the main reason for waiting. I started off by waiting until they were all 4 kilos, but as I have gotten more comfortable the age and the size that I am willing to do the operation has become smaller. During that period of time most of us will keep the babies on some kind of elemental feeding like elemental formula or breast milk, and we almost always will send them home on rectal stimulations or on irrigations to prevent obstruction.

Your last question had to do with a child who presents with Hirschsprung’s enterocolitis, which can be a very fulminant and very severe infection. I think it is clear that a child who presents extremely sick with enterocolitis should have a defunctioning stoma.

Not every baby is a good candidate for a primary pullthrough. However, we do see a lot of children who present with relatively mild enterocolitis. We usually treat them with antibiotics and irrigations, settle it down, and then go ahead and do a primary pullthrough. And my experience and the experience of most of my colleagues has been very good. We have had a very low postoperative rate of enterocolitis. So I think that not every baby with enterocolitis needs a colostomy.

Dr. Hartley S. Stern (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada): Dr. Langer, a very interesting paper, and I enjoyed it very much. I recognize that the patient population you are dealing with has not yet reached adolescence, but could you comment on the potential or theoretical benefits for sexual dysfunction over the other approaches?

Dr. Jacob C. Langer (Toronto, Ontario, Canada): Dr. Swenson actually alluded to that. I think 1 of the main rationales for the Soave operation in the first place was to avoid dissecting around the rectum, deep in the pelvis, and causing some kind of problem with sexual dysfunction later in life.

As Dr. Swenson has pointed out, there isn’t any evidence in the long-term follow-up studies that the Swenson operation results in an increased incidence of sexual dysfunction. So I don’t think that this approach has any proven benefit with respect to sexual dysfunction. The reason that I continue to do that little short submucosal dissection is just to avoid injury to the prostate or to the vagina when I am coming at it from below.

Dr. Arnold G. Coran (Ann Arbor, Michigan): Dr. Langer, a very nice presentation. Ann Arbor is happy to be part of this presentation. I have 1 question relating to the issue of enterocolitis.

Your incidence of 6%, as you know, is quite low. If 1 looks at a number of other large series that have been reported, it can range anywhere from 16 to as high as 30%. The problem is how you define enterocolitis.

Our impression in Michigan has been that, even though we have switched almost completely from the transabdominal endorectal pullthrough to the transanal, in fact enterocolitis has not really changed. I don’t know what our real numbers are, but it doesn’t appear to have changed in incidence. So I would like to know why you think it is so low and what your definition of enterocolitis is postoperative.

Dr. Jacob C. Langer (Toronto, Ontario, Canada): Thank you. That is a very important question. Unfortunately, there is no universally accepted definition of enterocolitis. It is like people say about pornography, you don’t know how to define it but you know it when you see it.

The problem with this study is that it was all based on self-reporting. This was basically surgeons at 6 centers sending me their results, and it was up to the surgeon to decide whether he or she thought that the patient had enterocolitis. So I have a feeling that this may be falsely low because of that deficiency in the study design. But Dan Teitelbaum and Mike Caty and I have actually embarked on a project to try and pin down a little bit better what the definition of enterocolitis is and to try and develop some kind of consensus so that people in the future when they are reporting results can compare 1 study to another and know that they are talking about the same thing.

Dr. Philip L. Glick (Buffalo, New York): Dr. Langer, I would like to congratulate you on your presentation and on the discussion. It is wonderful being here today.

You left out a group of patients, the ones with total colonic Hirschsprung’s disease. And we know these children do not do well with an ileoanal pullthrough, especially in the newborn period.

Are you advocating now that we do a laparoscopic biopsy before we start the ileoanal dissection to avoid the false positives and false negatives transition zones on the barium enemas to avoid getting into a situation where you have done your dissection and you wind up having a baby with total colonic Hirschsprung’s? Have you excluded those patients from this study?

Dr. Jacob C. Langer (Toronto, Ontario, Canada): The answer is yes, I am advocating that. However, I am not sure that I have universal agreement with that from all of my colleagues. My own personal opinion now that I have started to do this is routinely is that we should be identifying the transition zone pathologically before we start the anal dissection.

I would also say that not everybody agrees that an ileoanal pullthrough has poor results in patients with total colonic disease. The Ann Arbor Group, for example, prefers that operation for total colonic disease. And anytime you have multiple operations for a single disease you know that none of them are particularly good. I think that that is the case for total colonic Hirschsprung’s disease.

Dr. Fabrizio Michelassi (Chicago, Illinois): Dr. Langer, I rise to congratulate you on a clear and stimulating presentation. I perform adult surgery, and to me it is mind-boggling to think that you can remove the rectum and part of the sigmoid colon transanally; also it is somewhat concerning that this procedure may induce trauma to the anal sphincter which may manifest itself immediately or later in the life of the patient.

To this extent, I notice that 11% of your patients have perineal excoriation in the immediate postoperative period, which may speak to the existence of some perioperative incontinence. It is obviously difficult to evaluate incontinence in a newborn; but your data go back to 1995 and I would be interested in knowing the rate of incontinence in the now 7- or 8-year-old patients.

Obviously, long-term follow-up is important for any procedure, but even more so for procedures where functional results are part of the long-term outcomes. This will be important for patients as they age and especially in the girls that you operated on who may have other adverse events in life, such as childbirth, affecting their ultimate anal continence. Thank you very much.

Dr. Jacob C. Langer (Toronto, Ontario, Canada): Thank you for that question. It is very clear that we need long-term follow up. But it is going to take a long time to get it.

There is really no reason to think that the incontinence rates after this operation would be any different than the incontinence rates after a standard abdominal approach to any 1 of the pullthroughs. We are doing essentially the same operation. When you do an open Swenson or open Soave the anastomosis is done from below and there is a lot of retraction on the anal sphincter, so we wouldn’t expect any difference in incontinence rates. If you look at long-term follow-up studies, most of them, whatever operation you do, quote a long-term rate of incontinence of somewhere in the range of 10%. When we have looked at our small group that are now 3 or 4 or 5-year-old, we only have a couple of kids where the surgeon reported incontinence as a problem. And it was mild incontinence, which is why those children fell into the mild symptom group that I showed you.

It is an excellent question and we are going to have to follow it much longer, but we don’t have any apparent reason to believe that the incontinence rate will be any higher.

Dr. Murray F. Brennan (New York, New York): One of the things we did not compliment you on was the 14 mL blood loss. Many of the people in this audience work in institutions where initial access cannot be done with a 14 mL blood loss.

Footnotes

Reprints: Jacob C. Langer, MD, Chief, Pediatric General Surgery, Rm 1526, Hospital for Sick Children, 555 University Ave, Toronto, ON M5G 1X8 Canada. E-mail: jacob.langer@sickkids.ca.

REFERENCES

- 1.Langer JC, Fitzgerald PG, Winthrop AL, et al. One vs two stage Soave pull-through for Hirschsprung's disease in the first year of life. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:33-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teitelbaum DH, Cilley RE, Sherman NJ, et al. A decade of experience with the primary pull-through for Hirschsprung disease in the newborn period: a multicenter analysis of outcomes. Ann Surg. 2000;232:372-380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pierro A, Fasoli L, Kiely EM, et al. Staged pull-through for rectosigmoid Hirschsprung's disease is not safer than primary pull-through. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:505-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Georgeson KE, Cohen RD, Hebra A, et al. Primary laparoscopic-assisted endorectal colon pull-through for Hirschsprung's disease: a new gold standard. Ann Surg. 1999;229:678-683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langer JC, Minkes RK, Mazziotti MV, et al. Transanal one-stage Soave procedure for infants with Hirschsprung disease. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:148-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langer JC, Seifert M, Minkes RK. One-stage Soave pullthrough for Hirschsprung disease: a comparison of the transanal vs open approaches. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:820-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De la Torre-Mondragon L, Ortega-Salgado JA. Transanal endorectal pull-through for Hirschsprung's disease. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:1283-1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De la Torre L, Ortega A. Transanal versus open endorectal pull-through for Hirschsprung's disease. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:1630-1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albanese CT, Jennings RW, Smith B, et al. Perineal one-stage pull-through for Hirschsprung's disease. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:377-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hollwarth ME, Rivosecchi M, Schleef J, et al. The role of transanal endorectal pull-through in the treatment of Hirschsrpung's disease—a multicenter experience. Pediatr Surg Int. 2002;18:344-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shankar KR, Losty PD, Lamont GL, et al. Transanal endorectal coloanal surgery for Hirschsprung's disease: experience in two centers. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:1209-1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teeraratkul S. Transanal one-stage endorectal pull-through for Hirschsprung's disease in infants and children. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:184-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao Y, Li G, Zhang X, et al. Primary transanal rectosigmoidectomy for Hirschsprung's disease: preliminary results in the initial 33 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:1816-1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vijaykumar Chattopadhyay A, Patra R, et al. Soave procedure for infants with Hirschsprung's disease. Indian J Pediatr. 2002;69:571-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langer JC. Repeat pullthrough surgery for complicated Hirschsprung disease: indications, techniques, and results. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:1136-1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoehner JC, Ein SH, Shandling B, Kim PCW. Long-term morbidity in total colonic aganglionosis. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:961-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Proctor ML, Traubici J, Langer JC, et al. Correlation between radiographic transition zone and level of aganglionosis in Hirschsprung's disease: implications for surgical approach. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:775-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamataka A, Yoshida R, Kobayashi H, et al. Laparoscopy-assisted suction colonic biopsy and intraoperative rapid acetylcholinesterase staining during transanal pull-through for Hirschsprung's disease. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:1661-1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]