Abstract

Objective:

To identify risk factors associated with ileal pouch failure and to develop a multifactorial model for quantifying the risk of failure in individual patients.

Summary Background Data:

Ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) has become the treatment choice for most patients with ulcerative colitis and familial adenomatous polyposis who require surgery. At present, there are no published studies that investigate collectively the interrelation of factors related to ileal pouch failure, nor are there any predictive indices for risk stratification of patients undergoing IPAA surgery.

Methods:

Data from 23 preoperative, 7 intraoperative, and 10 postoperative risk factors were recorded from 1,965 patients undergoing restorative proctocolectomy in a single center between 1983 and 2001. Primary end point was ileal pouch failure during the follow-up period of up to 19 years. The “CCF ileal pouch failure” model was developed using a parametric survival analysis and a 70%:30% split-sample validation technique for model training and testing.

Results:

The median patient follow-up was 4.1 year (range, 0–19 years). Five-year ileal pouch survival was 95.6% (95% CI, 94.4–96.7). The following risk factors were found to be independent predictors of pouch survival and were used in the final multivariate model: patient diagnosis, prior anal pathology, abnormal anal manometry, patient comorbidity, pouch-perineal or pouch-vaginal fistulae, pelvic sepsis, anastomotic stricture and separation. The model accurately predicted the risk of ileal pouch failure with adequate calibration statistics (Hosmer Lemeshow χ2 = 3.001; P = 0.557) and an area under the receiver operating characteristics curve of 82.0%.

Conclusions:

The CCF ileal pouch failure model is a simple and accurate way of predicting the risk of ileal pouch failure in clinical practice on a longitudinal basis. It may play an important role in providing risk estimates for patients wishing to make informed choices on the type of treatment offered to them.

The present study describes the development of a multifactorial model for quantifying the risk of ileal pouch failure (IPF) for patients undergoing restorative proctocolectomy. Eight independent risk factors were used in the development of the CCF-IPF model, which accurately predicted the risk of ileal pouch failure on a longitudinal basis.

Restorative proctocolectomy (RPC) and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) was first introduced by Parks and Nicholls in 1978.1,2 Since its inception, the technique has gained acceptance as the treatment of choice for most patients with ulcerative colitis and for patients with familial adenomatous polyposis who require surgery. RPC removes the diseased bowel, reduces the risk of cancer, and preserves the natural route of defecation while maintaining fecal continence, thus avoiding the need for a permanent stoma. Although patients can enjoy high quality of life with good functional outcomes, IPAA surgery can be associated with significant complications, leading to pouch excision or permanent diversion in 3.5–10% of cases in large series.3–5 Numerous studies have examined the reasons for ileal pouch failure and have advocated that unrecognized Crohn disease,6,7 fistula formation,8 pelvic sepsis,9 and mucosal proctectomy10 may contribute to poor functional outcomes requiring rediversion or ileal pouch excision. Although Crohn disease and its associated manifestations represent the most important determinants of ileal pouch failure, there are no studies that describe a definitive index for quantifying the risk of ileal pouch failure after RPC.

The aims of the present study were to identify the important risk factors associated with ileal pelvic pouch failure and to develop a predictive model for quantifying the risk of ileal pouch failure in individual patients on a longitudinal basis. In conjunction with the multidisciplinary approach to patient management, the model should be readily applicable in everyday practice for perioperative counseling of patients and their caregivers.

METHODS

Data Sources

Patients undergoing primary restorative proctocolectomy with IPAA for all indications between February 1983 and December 2001 were identified through the Cleveland Clinic Ileal Pouch Database in the Department of Colorectal Surgery. The database provided a comprehensive data set comprising patient demographic characteristics, preoperative assessment, surgical treatment, postoperative course, pathology section, long-term complications, and functional outcomes. Data validation was performed by a single investigator by requesting duplicate information from patient charts. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

End Point and Risk Factors

The primary outcome was ileoanal pouch failure, defined as excision of the ileoanal pouch, formation of a permanent ileostomy, or pouch-related mortality any time during the follow-up period. The risk factors studied included the presence of prior anal pathology (perianal abscesses, fistula-in-ano, fissure-in-ano, or significant hemorrhoids/skin tags), extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease, patient comorbidity (cardiac, respiratory, renal impairment, diabetes, or morbid obesity), preoperative diagnosis, anal sphincter manometry (mean resting pressure and squeeze pressure measured in mm Hg), previous abdominal operations, details on surgical procedures, postoperative pathologic diagnoses along with the early (within 30-days after surgery) and late complications. Pelvic sepsis was defined as the presence of parapouchal abscesses and excluded anastomotic leak and pouch-related fistulae, which were also recorded as separate complications. Chronic pouchitis was defined as 4 or more episodes of pouchitis per year or the need for chronic antibiotic, immunosuppressive therapy to control symptoms, in addition to endoscopic evidence of pouch inflammation (Table 1).

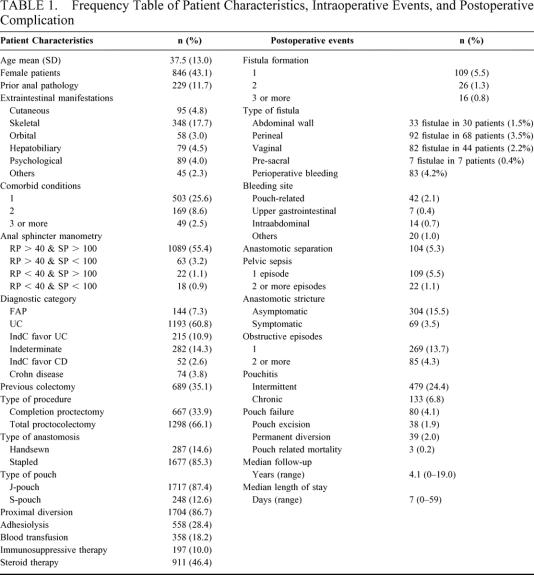

TABLE 1. Frequency Table of Patient Characteristics, Intraoperative Events, and Postoperative Complication

Statistical Analysis and Model Development

The ileal pouch failure rate was regarded as a time-dependent variable, and unifactorial survival analysis based on the Cox proportional hazards regression methodology was undertaken to identify individual risk factors related to IPAA failure. Adjustment was made for time-dependent variables and censored data, ie, patients lost on follow-up, or whose ileal pouch was in situ and functioning at the time of the analysis (last follow-up visit). Risk factors with a univariate P < 0.25 were included in the multivariate analysis. To maximize the information extracted from the predictor and response variables the technique of median imputation was used to substitute for incomplete data.11 Multivariate Cox-regression analysis was used to provide the β-coefficients for each independent risk-factor. These were subsequently used as weights in the derivation of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation ileal pouch failure (CCF-IPF) score. The individual patient probability of ileal pouch failure (Ft) at a particular point in time measured in years from the time of surgery (t) was then calculated by entering the CCF-IPF score as a single independent predictor into a survival parametric model based on the Weibull distribution using the following equation:

Model Validation

The model was internally validated by dividing the data set into 2 distinct sets. The model was generated on 70% of the study population and the remaining 30% of patients used for testing the performance of the model. This split-sample validation procedure was repeated 10,000 times using a resampling method called “bootstrapping” to calculate standard errors and to correct bias in the parameter estimation.12 The model estimates were adjusted for the clustering of adverse outcomes between surgeons. The performance of the model was evaluated by measures of calibration, discrimination, and subgroup analysis. Calibration or goodness-of-fit refers to the ability of the model to assign the correct probabilities of outcome to individual patients and was measured by the Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2 statistic.13 Smaller values represent better model calibration. Model discrimination refers to the ability of the model to assign higher probabilities of pouch failure to patients who actually did not retain their pelvic pouch compared with those who did. This was measured by the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Values ranging from 70% to 80% represent reasonable discrimination and value exceeding 80% represent good discrimination.14 Subgroup analysis was performed by comparing the observed and model-predicted IPAA failure rate on a random sample of 1000 patients drawn from the original population.

Software

The following statistical software packages were used to develop the risk model: Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 11 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL) and Intercooled STATA 6.0 for Windows (STATA Corporation).

RESULTS

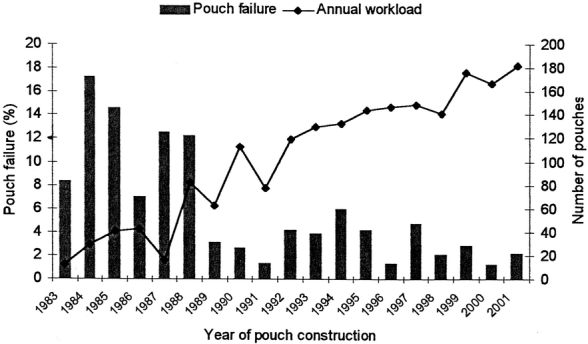

A total of 2591 primary pelvic pouch surgeries have been performed at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation by twelve surgeons from February 1983 to April 2003. A total of 1965 patients with well-validated outcomes and risk factors were identified for the purposes of the present study. The patients’ preoperative characteristics, operative details, and postoperative complications are shown in Table 1. The study population comprised 144 (0.7%) patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP); 1,193 (60.7%) patients with ulcerative colitis (UC); 549 (27.9%) patients with indeterminate colitis; and 74 (3.8%) patients with Crohn disease (CD). The median patient follow-up was 4.1 year (ranging between 0 and 19 years). The annual workload of RCP increased from an average of 40 cases per year before 1990 to 160 cases per year after 1995. Prior to 1987, the majority of pelvic pouches (99%; n = 125) were handsewn in contrast to the period from 1987 to 2001 whereby 91.1% (1,676 of 1,839) of ileal pouches were stapled.

Of the 1,965 patients who had RPC, 38 patients (1.9%) required pouch excision, 39 patients (2.0%) underwent permanent diversion, and a further 3 patients (0.2%) died within the early postoperative period, for a total of 80 patients (4.1%) classified as having pouch failure. There were 11 early failures (13.8%) within 6 months of the operation, and the remaining 69 failures occurred between 7 months and 15 years (median, 3.3 years) after surgery. The number of pouches failing decreased significantly over time, from 12 of 82 pouches (14.6%) failing during the first 3 years of the study (1983–1985) to 11 of 525 pouches (2.1%) failing during the last 3 years (1999–2001), P < 0.001. The overall cumulative 3-year (n = 1241), 5-year (n = 906), and 10-year (n = 372) IPAA survival was 96.5% (95% CI, 95.5–97.4%), 95.7% (95% CI, 94.6–96.8%), and 93.4% (95% CI, 92.2–95.3%), respectively.

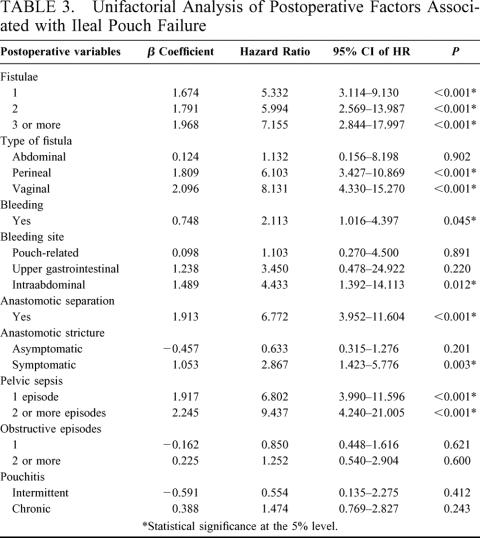

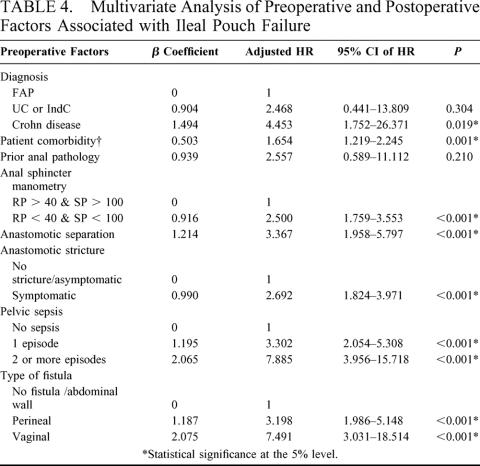

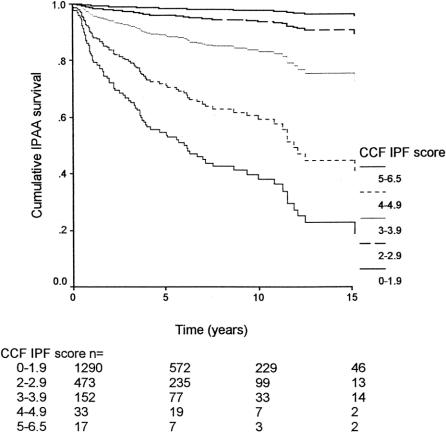

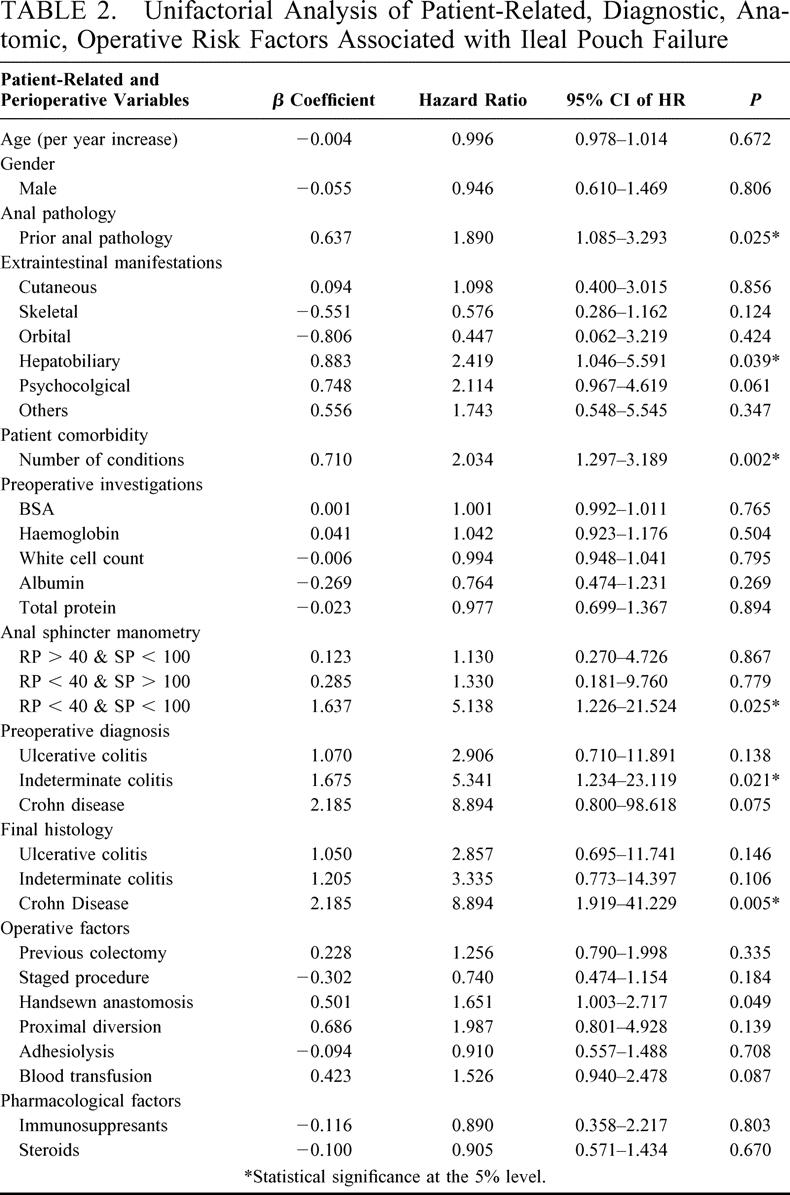

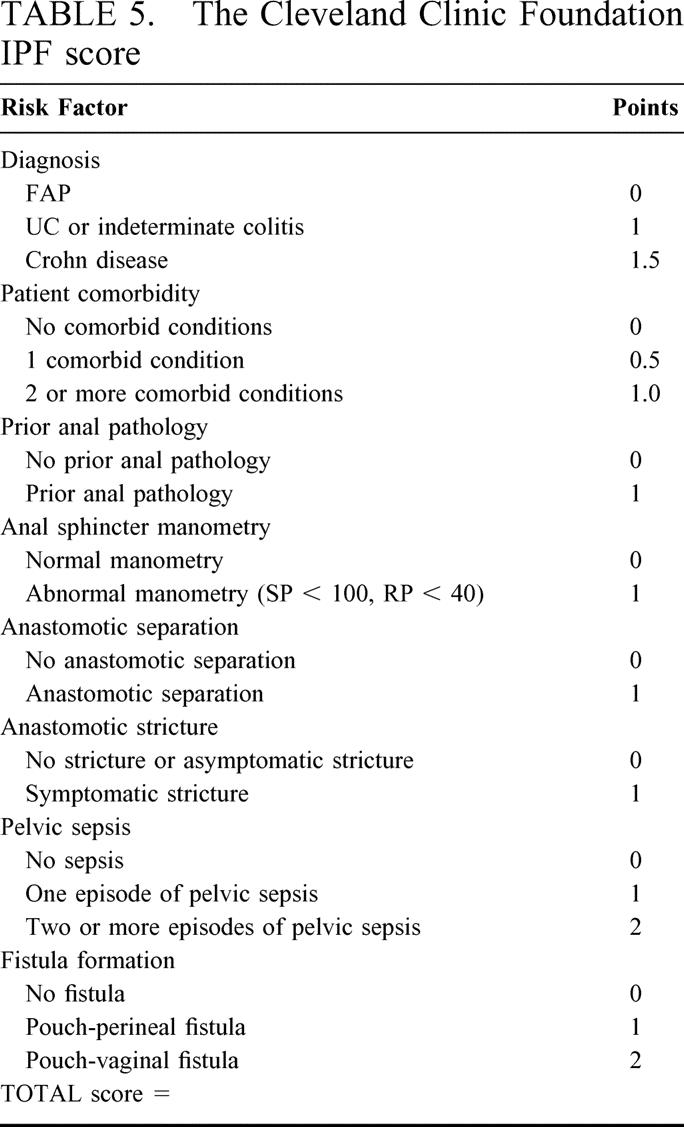

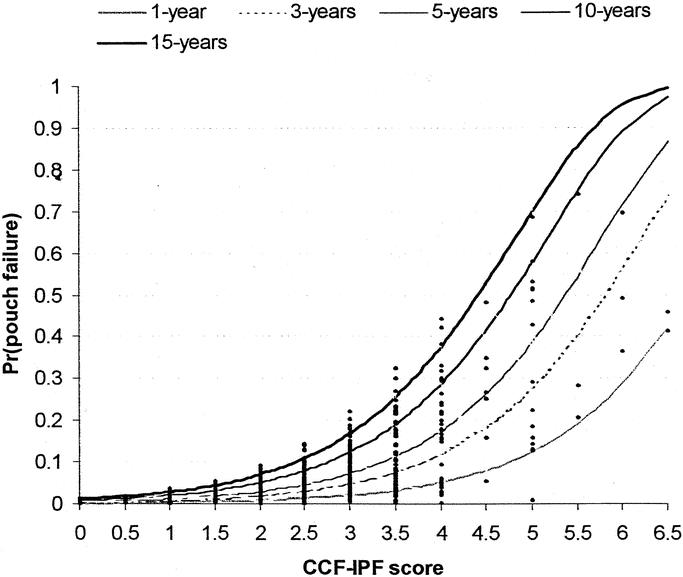

A total of 23 preoperative, 7 intraoperative, and 10 postoperative risk factors were considered in the univariate analysis, the results of which are shown in Tables 2 and 3. On multivariate analysis, 8 factors were found to be independent predictors of ileal pouch failure. These variables together with the β-coefficients of the Cox model, the hazard ratios, and the 95% CI are shown in Table 4. In generating the multifactorial model, first-order interactions between these independent risk factors were also considered, but none of these exceeded the significance threshold for inclusion into the model. The Cleveland Clinic Foundation ileal pouch failure score is shown in Table 5. Each risk factor was categorized into relevant subgroups, with values derived from the β-coefficients of the Cox-regression analysis as shown in Tables 3 and 4. Patients with ulcerative colitis and indeterminate colitis were grouped together, as on multifactorial analysis similar hazard ratios were obtained. The probability of ileal pouch failure at 1, 2, 5, 10, and 15 years follow-up, based on the CCF-IPF score, are shown as individual prediction curves in Figure 2. In addition, the probability of ileal pouch failure as calculated by the Weibull survival equation (CCF-IPF model) for each patient in the study was plotted against the CCF-IPF score on the same graph.

TABLE 2. Unifactorial Analysis of Patient-Related, Diagnostic, Anatomic, Operative Risk Factors Associated with Ileal Pouch Failure

TABLE 3. Unifactorial Analysis of Postoperative Factors Associated with Ileal Pouch Failure

TABLE 4. Multivariate Analysis of Preoperative and Postoperative Factors Associated with Ileal Pouch Failure

TABLE 5. The Cleveland Clinic Foundation IPF score

FIGURE 2. Probability of ileal pouch failure at 1, 2, 5, 10, and 15 years follow-up based on the CCF-IPF score as calculated by the Weibull survival model (CCF-IPF model). The individual patient probabilities are shown (diamonds).

Model Performance

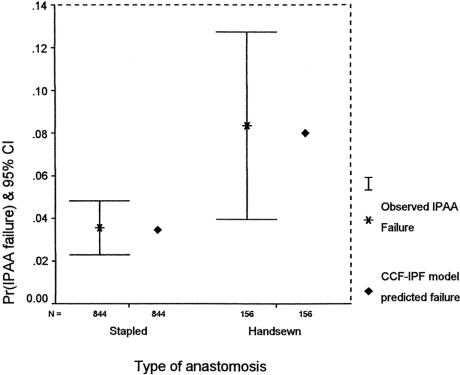

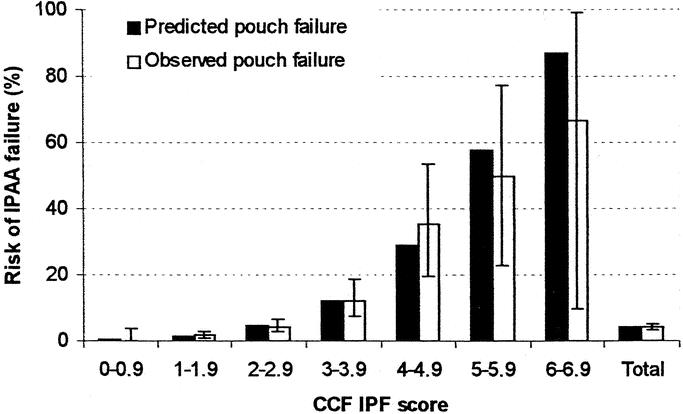

The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve obtained by the CCF-IPF score and model was 82.0% (95% CI, 77.5–86.5%). Model calibration was evaluated by comparing the estimated risk of pouch failure calculated by the CCF-IPF model with the observed pouch failure rate (Fig. 3). There was very good agreement between the observed and expected pouch failure rate (Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2 = 3.007; 5 degrees of freedom; P = 0.557). At 1-year follow-up, no significant difference was evident between observed and expected ileal pouch failure (Fisher exact test, P = 0.540). On subgroup analysis, the predicted risk of ileal pouch failure as calculated by the CCF-IPF model for the 2 types of IPAA anastomoses was well within the confidence intervals of the observed outcome as shown in Figure 4 (P = 0.847). Survival curves for IPAA surgery have been constructed for various groups of CCF-IPF scores, as shown in Figure 5. At high and low CCF-IPF scores, the cases numbers were too small for individual scores to be meaningful; these have been grouped together, and actuarial survival curves have been constructed for illustrative purposes for the very low (<2) and the very high (≥5) scores, respectively.

FIGURE 3. Calibration chart of the CCF-IPF score. The observed and predicted ileal pouch failure rates are displayed along with the 95% CI around the observed outcome.

FIGURE 4. Comparison of observed and model-predicted ileal pouch failure rate by type of anastomosis on a random sample of 1000 patients.

FIGURE 5. Cumulative ileal pouch survival by CCF-IPF score.

DISCUSSION

Restorative proctocolectomy has been shown to be an effective and safe surgical therapy for patients with UC or FAP. It is associated with a low perioperative mortality and satisfactory functional results. Despite its wide acceptance, the characteristics of patients with pouch failure are known to vary between institutions: Körsgen7 reported a failure rate of 12.7% resulting from pouch ischemia (19.3%), pelvic sepsis/fistulae (35.5%), Crohn disease (12.9%), anastomotic stricture (16.1%), and poor function including pouchitis (16.1%). A different rate of pouch failure (3.8%) was reported by Galandiuk et al15 in a series of 982 cases whereby anastomotic strictures (19%), pelvic sepsis/fistulae (73%), and poor function (8%) resulted in IPAA failure. In a recent study of 1005 patients by our group, recurrent pouch-vaginal fistulae (17.6%), perianal sepsis (19.4%), pelvic sepsis (17.4%), recurrent pouchitis (20.5%), and poor function (8.8%) were the main causes of pouch failure.3 The variation in the preoperative investigations, operative techniques, and mode of follow-up also limits the comparison of results between centers. As surgery is moving rapidly into an era of public and professional accountability for clinical outcomes,16 predictive indexes are required for quantifying operative risk following IPAA surgery on the basis of the patient’s comorbid condition and the complexity of the proposed treatment. Patients may then be able to make better-informed choices on the basis of an objective estimate of risk, guided by the clinicians responsible for the patient’s care.

Our study design has a number of advantages. It provided extensive preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative data obtained from direct contact with patients at each of the preoperative and follow-up consultations. Follow-up was of adequate duration (median, 4.1 year), with a focus on pouch failure among other complications. The present report describes a relatively simple additive scoring system for calculating the risk of ileal pouch failure at particular time intervals for patients undergoing RPC. Pouch failure was regarded as a time-dependent outcome, and a semiparametric Cox survival model was initially used for the construction of the CCF-IPF score. As the Cox model merely provided adjusted hazard ratios for groups of patients, a parametric survival model based on the Weibull distribution was subsequently used to convert the CCF-IPF score into individual probabilities of ileal pouch failure (CCF-IPF model). This methodology has several advantages over other known techniques such as logistic regression analysis, as it accounts for variable duration of follow-up, censoring of subjects, and proportionality of event occurrence. Predictive models based on nonlinear methods of analysis such as artificial neural networks and expert systems17 are attractive alternatives for modeling IPAA survival; however, the use of conventional survival analysis may offer similar results with better construct and face validity and acceptability by clinicians.18

The final CCF-IPF score comprised 8 risk factors that were selected on the basis of statistical significance and clinical relevance. Consistent with previous reports, the most important determinant for pouch failure was the formation of pouch-perineal or pouch-vaginal fistulae, often preceded by pelvic or perineal sepsis.7–9 In our study, the diagnosis of Crohn disease was associated with a 9-fold increase in the likelihood of pouch failure, an effect that was diminished on multivariate analysis to 4-fold as additional factors (such as fistula formation or perianal sepsis) were introduced into the model that in themselves are more likely to be associated with Crohn disease rather than UC or FAP (ie, confounding variables). Other series have also highlighted the importance of unsuspected Crohn disease as an independent predictor of pouch failure.19,20 In our study, prior anal pathology was also associated with pouch failure; however, this did not reach statistical significance on multivariate analysis. This was in line with the study of 753 patients by Richard et al,21 who reported a 1.5-fold increase in pouch failure rate in patients with prior anal pathology, a difference that was not statistically significant. In the same study, prior anal disease significantly increased the risk of developing ileoanal anastomotic separation or perianal complications; we therefore elected to retain this risk factor in the CCF-IPF score, as it was considered to be clinically relevant and was found to enhance the predictive ability of the model. In contrast to previous reports,22 the present study demonstrated a 2.5-fold increase in the likelihood of pouch failure for patients with abnormal preoperative anal manometric findings (squeeze pressure ≤ 100 mm Hg; resting pressure ≤ 40 mm Hg). The effect of comorbid disease on long-term pouch outcome was also considered. In agreement with other studies on multivariate analysis, we did not demonstrate an association between pouch failure and pouchitis.9 The 4 preoperative risk factors may be used prior to surgery for providing the best possible information to patients and their caregivers as part of the process of informed consent. Information relating to postoperative adverse events can be used by the predictive model during the follow-up period to provide additional information relating to the patient’s prognosis.

In the present study, failure rates were higher during the early years of pouch construction, possibly reflecting the effect of the learning curve, the use of handsewn anastomosis,23 and as one might expect, a greater number of pouch failures would occur with a longer period of follow-up. Ileal pouch failure following IPAA surgery depends on a multitude of risk factors, some of which have not been measured in the present study such as functional outcomes, many of which interact in a “nonlineal” fashion. Early pouch failure is usually rare8 and, although possibly related to technically difficult operations with increased tension in the anastomosis and possible pouch ischemia,7 it is difficult to quantify or incorporate such factors in a multifactorial model as a result of their subjective nature.

CONCLUSION

The Cleveland Clinic Foundation IPF model was developed from a large, well-validated database, it is simple to use, and it can be readily applied in everyday surgical practice. The model was internally validated for the study population and was found to be accurate in predicting the risk of pouch failure on a longitudinal basis. Although the CCF-IPF model would require external validation by testing the model on data from other centers, it represents the first attempt in providing risk estimates for patients wishing to make informed choices on the type of treatment offered to them.

FIGURE 1. Variation of pouch failure rate by year of pouch construction (bar chart). The annual workload of ileal pouch procedures at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation is also shown (line chart).

Discussion

Dr. James M. Becker (Boston, Massachusetts): Our recently completed meta-analysis of over 8500 patients that have undergone ileoanal surgery over the last 20 years in 20 major centers around the country suggested that the overall worldwide pouch failure rate was relatively high, about 6%. However, if 1 focuses on those reports from the last 5 years, the failure rate has dropped considerably, down closer to 2%. This is undoubtedly due to more careful patient selection, more definitive preoperative diagnosis, more experienced surgeons with better surgical techniques, improved postoperative care, and patient follow-up and education. The study today presented from the Cleveland Clinic provides very elegant statistical indications that that is the case.

It is interesting in reviewing all of these series that the major causes of failure were associated either directly with Crohn’s disease or with suspected Crohn’s-associated complications, including fistulas, perianal sepsis, sinus tracts, etc. My own experience of over 660 of these operations confirms that as well. The failure rate has been about 2%, and virtually all those patients who failed had either proven Crohn’s or strongly suspected Crohn’s-associated problems. Incidentally, all 663 patients had mucosal proctectomy with a hand-sewn ileoanal J-pouch-anal anastomosis.

The Cleveland Clinic series presented today suggested an overall failure rate over this 20-year period of about 4%, although they stratified the failures by time during the overall study period. In the 1980s the failure rate was around 15%. In the 1990s it dropped down to about 4%. In the last 5 years it has been approximately 2%. Again, the main contributor to failure was Crohn’s disease or suspected Crohn’s-related complications.

So I understand that to generate a comprehensive multifactorial model for a complex multivariate analysis such as this, one must include all the potential independent risk factors associated with long-term failure of the pouch; however, it appears that the majority of pre and postoperative risk factors used to develop, validate, and test the model demonstrated were all associated directly with Crohn’s disease or suspected Crohn’s-like manifestations. Do the authors feel that these determinants are truly independent of each other, or is there a unifying theme?

As was reported, 12 surgeons contributed to this study at the Cleveland Clinic. I wonder if the authors could comment on the impact of individual surgeon experience within that single institution on pouch survival?

I am wondering about the median four-year follow-up. Is that truly representative of a patient population that spans a 20-year period? Could the authors comment on why their failure rate has dropped so low in the last 5 years?

I am unclear about the issue of indeterminate colitis. This was demonstrated to be a strong preoperative determinant of subsequent pouch failure, yet in a multivariate analysis indeterminate colitis and ulcerative colitis were combined, and in the weighted scoring system they were given the same weight. Thus, do the authors think that patients that have indeterminate colitis should not undergo ileal pouch-anal anastomosis? If so, that would tend to contradict their recent publication that suggested that indeterminate colitis patients do as well long term as patients with classic ulcerative colitis. Have the authors used the biochemical markers pANCA and pASCA to try to clarify the diagnosis?

Finally, could the authors comment on the issue of mucosectomy and handsewn ileoanal anastomosis as a true indicator of pouch failure?

Dr. Paris Tekkis (Cleveland, Ohio): I would like to thank the discussant for the most valuable comments.

In relation to the first question the majority of patients with adverse outcomes could well be related to suspected or unrecognized Crohn’s disease. In the present study, Crohn’s disease was an independent predictor of ileal pouch failure, as well as other preoperative factors possibly related to Crohn’s disease. In particular, prior anal pathology in the form of perianal sepsis, or fistula-in-ano could represent unrecognized Crohn’s disease in the preoperative setting. A total of 80 patients underwent pouch excision or permanent diversion. As a rule of thumb a predictive model should comprise 1 risk factor per 10 adverse outcomes, therefore a maximum of 8 variables could be included in the multivariate analysis thus maintaining adequate power to detect the independence of each risk factor. We have not entered any interaction terms within the CCF-ileal pouch failure model as none of these exceeded the significance threshold for inclusion into the model. In the future, as more patients are entered into the model, we may be able to evaluate and possibly include interaction terms such as the product of Crohn’s disease and postoperative fistula formation.

It would be virtually impossible to evaluate the impact of individual surgeons or institutions on ileal pouch failure at present. The analysis was done by taking into account the clustering of patients within the practice of individual surgeons. The hazard ratios for each factor were adjusted for what we call the “surgeon effect.” We did not demonstrate a significant difference in ileal pouch failure rate between surgeons, although we did identify an initial learning curve in half of all staff undertaking IPAA surgery. This initial learning phase can be incorporated into the model if indicated.

With regards to the adequacy of the follow-up period in the study, the maximum follow-up was 19 years and the median follow-up was 4.1 year. One-quarter of all patients had a follow-up period of 10 or more years. As ileal pouch failure is a time dependent variable we were able to prove risk estimates for ileal pouch failure up to a period of 15 years following IPAA surgery.

We have all seen a reduction in the ileal pouch failure rate over the past 5 years. One possible factor for the apparent improvement in ileal pouch outcomes is the surgeon experience and familiarity in the techniques of IPAA surgery. More importantly is the length of follow-up. Patients who are monitored over a longer time period, are more likely to have an adverse event although this effect plateaus off after 10 to 15 years. What we have seen in the last couple of years, are pouch failure rates in the order of 2% possibly representing a shorter patient follow-up period.

With regards to the question on indeterminate colitis 27.6% of the total study population were classed as indeterminate colitics. Forty percent of these patients favored mucosal ulcerative colitis and rather than classifying them as a separate group we have incorporated them into the diagnostic category of indeterminate colitis. On multivariate analysis we have not shown any significant differences in pouch failure rate between these 2 groups. A recent publication by Delaney et al in the Annals of Surgery (2002; 246: 43–8) evaluated the quality of life and pouch survival in patients with MUC and indeterminate colitis. The authors demonstrated differences in septic complications between the 2 groups but did not show any differences in pouch survival. Similar results were also obtained in the present study.

With regards to the usage of pANCA and ASCA serology as a diagnostic modality for Crohn’s disease, we are unsure of its cost-effectiveness. At present these tests do not form part of our routine preoperative workup of patients undergoing IPAA surgery and I am unable to comment to that effect.

Finally, with regards to the choice of mucosectomy versus handsewn anastomosis we need to be sensible and selective in the choice of patients. Mucosectomy and hand-sewn anastomosis is indicated in redo ileal pouch surgery, in patients presenting with rectal cancers and in patients with high grade dysplasia in the lower rectum. A previous study by Remzi et al (Diseases of the Colon and Rectum; 2001; 40: 1590–6) demonstrated better functional outcomes in patients with stapled ileoanal anastomosis. In the present study having adjusted for the various risk factors, we have not shown a significant difference in the pouch failure rates between the 2 anastomotic techniques. We know that there are possible differences in the incidence of pelvic sepsis and other complications between the 2 techniques, but this is not the issue or theme of this meeting.

Dr. Eric W. Fonkalsrud (Santa Monica, California): I would like to congratulate the authors for calling to our attention the risk factors which should be taken into consideration in deciding which operation to perform for colitis and polyposis based on your large clinical experience at the Cleveland Clinic.

There are a few other factors that we have found in our experience that increase the risk for complications and pouch failure, such as obesity with a BMI over 30, use of long-term steroids, and use of long-term immunosuppressive medications. In addition, children who had the diagnosis of colitis made before the age of 16 years with the operation performed at an early age are also at a high risk for complications. Children are more likely to have pancolitis than are the adults who come to surgery. Could you indicate what you recommend for your patients who have pouch failure; ie, do you do a Kock pouch, a permanent ileostomy, or some type of reconstruction?

Lastly, there are a group of patients who underwent operation many years ago using S-pouches, W-pouches, or lateral pouches, all with spouts. We have found that patients with these pouches have a higher failure rate than those with the J-pouch and often benefit from pouch reconstruction. Perhaps you could make some comments.

Dr. Paris Tekkis (Cleveland, Ohio): I thank the discussants for their valuable comments. I would like to respond to the first 3 questions and with reference to Dr. Rothenberger’s remarks, there are technical and philosophical issues which I would defer to Dr. Fazio.

With regards to the body mass index, steroid and immunosuppressive therapy, we have investigated the relationship of these factors and were not found to be independent predictors of ileal pouch failure. Although, we are aware that these factors can be associated with a higher incidence of postoperative complications we have not demonstrated a significant relationship with ileal pouch failure.

With regards to children below the age of 16, we have not evaluated whether this particular group of patients might be at a higher risk of ileal pouch failure. This is an issue that we would look into it in future studies.

With regards to the type of pouch construction, this was not found to be an independent predictor of outcome. The number of S-pouches were possibly too few to detect a significant difference pouch failure rate.

Dr. Victor W. Fazio (Cleveland, Ohio): I want to thank Dr. Fonkalsrud for his remarks. He is, of course, 1 of [b]the authorities with this particular type of operation.

As to what to do when a pouch fails depends on a number of factors. These include adequacy of anal sphincters; rigidity of the anorectum; the likelihood that the diagnosis is in fact ulcerative colitis versus Crohn’s disease; presence of comorbidity; whether the patient is aged, and, above all, that the patient is fully informed and consents to surgery. We can give patients some idea, depending on presence of specific features, what the success rate of reoperative and particularly redo pelvic pouch surgery is.

For example, if you perform a redo pouch anal anastomosis for a firmly established diagnosis of ulcerative colitis, you can tell that patient that they will have about a 90% chance of keeping that pouch at 3 years and about a 75% chance of keeping it over 5 years. Whereas with Crohn’s disease fewer than half will keep their pouch if you redo it at 5 years. That allows the patient to participate in that decision making.

I would agree about the issue of the spout and the type of pouch that is used. Certainly, the long-exit conduits which were so much used in the ’80s associated with the S-pouch had a very high revision rate. And indeed unless the exit conduit is kept less than 3 cm, then one can expect the obstructive defecation to occur, mandating further surgery. We will reoperate on such patients when the above exclusions have been made.

And then to make the decision as to whether or not to do a continent ileostomy by preference in the event that the anorectum is no longer usable, I think that requires a whole new set of discussions and philosophies. Because after all, if you have lost the pouch there and you make a new continent ileostomy, you always have to, I think, anticipate that that may be lost in turn in the course of time. And how can that patient suffer through 2 pouch losses? We have plenty of data on the effect of 1 pouch loss and patients can get by all right, but 2 is another matter.

Dr. David A. Rothenberger (Minneapolis, Minnesota): The authors from Cleveland certainly have presented a benchmark paper for us to try to match in our clinics. Just 1 quick question for Dr. Fazio.

You commented that pouch failure in your series was most correlated with pouch perineal or pouch vaginal fistulas often preceded by pelvic or perineal sepsis. What can we do to further decrease the incidence of sepsis? How do you manage the patient if you start to sense that sepsis is developing in the postoperative period? What are your steps to intervene before a fistula develops?

Thank you for providing me your manuscript in advance of the meeting. I enjoyed reviewing your work.

Dr. Victor W. Fazio (Cleveland, Ohio): Thank you, Dr. Rothenberger. I think that a number of things can be done to reduce the chance of sepsis.

The first is to stop doing the operation. And that may not be as silly as it sounds. Because I think there is a learning curve that is associated with this operation that perhaps it should be done by those who have been trained in how to do it to the start with. There are preparation antibiotics. Avoidance of using the operation in patients with Crohn’s disease will lessen the rate. Even indeterminate colitis surgery will lessen the rate.

But this begs the philosophical question of what percentage risk is a patient prepared to take for getting a complication as opposed to staying with an ileostomy? And that now allows to us do quantifiable risk assessment.

Technical aspects include the use of a temporary ileostomy, minimizing tension, I believe a staple anastomosis certainly in the short term provides less complication rates, and there are techniques to provide lengthening of the bowel with a tension-free anastomosis. So these are the main things—and pouch vaginal fistula, the big thing, of course, is to use stapled operations to make sure that the stapled head and cartridge don’t incorporate the posterior vaginal wall.

As far as the management of the sepsis is concerned, to take a leaf from the pages of Gilbert and Sullivan: You let the punishment fit the crime. In this case this means that minimal sepsis or local perianal associated with low fistulas, that things like tree tongs or even localized patch advancements can be performed. For the more complex ones, especially those associated with anastomotic leak and rigidity of the pouch that precludes the advancement of the pouch, then transabdominoanal operation I think is the procedure of choice with pouch advancement. Thank you.

Footnotes

Reprints: Victor W. Fazio, MB, MS, Department of Colorectal Surgery/A30, The Cleveland Clinic Foundation, 9500 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, OH 44195. Email: faziov@ccg.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Parks AG, Nicholls RJ. Proctocolectomy without ileostomy for ulcerative colitis. Br Med J. 1978;2:85–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Setti-Carraro P, Ritchie JK, Wilkinson KH, et al. The first 10 years’ experience of restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1994;35:1070–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fazio VW, Ziv Y, Church JM, et al. Ileal pouch-anal anastomoses complications and function in 1005 patients. Ann Surg. 1995;222:120–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belliveau P, Trudel J, Vasilevsky CA, et al. Ileoanal anastomosis with reservoirs: complications and long-term results. Can J Surg. 1999;42:345–352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meagher AP, Farouk R, Dozois RR, et al. Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis: complications and long-term outcome in 1310 patients. Br J Surg. 1998;85:800–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foley EF, Schoetz DJ Jr, Roberts PL, et al. Rediversion after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Causes of failures and predictors of subsequent pouch salvage. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:793–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korsgen S, Keighley MR. Causes of failure and life expectancy of the ileoanal pouch. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1997;12:4–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lepisto A, Luukkonen P, Jarvinen HJ. Cumulative failure rate of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis and quality of life after failure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1289–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacRae HM, McLeod RS, Cohen Z, et al. Risk factors for pelvic pouch failure. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:257–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becker JM, LaMorte W, St Marie G, et al. Extent of smooth muscle resection during mucosectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis affects anorectal physiology and functional outcome. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:653–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrell FE, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med. 1996;15:361–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Efron B, Tibshirani R. An introduction to the bootstrap. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143:29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galandiuk S, Scott NA, Dozois RR, et al. Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Reoperation for pouch-related complications. Ann Surg. 1990;212:446–452; discussion 52–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Spiegelhalter DJ, Aylin P, Best NG, et al. Commissioned analysis of surgical performance by using routine data: lessons from Bristol inquiry. J R Statist Soc A. 2002;165:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sangent DJ. Comparison of artificial neural networks with other statistical approches. Cancer. 2001;91:1636–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bostwick DG, Burke HB. Prediction of individual patient outcome in cancer: comparison of artificial neural networks and Kaplan–Meier methods. Cancer. 2001;91:1643–1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peyregne V, Francois Y, Gilly FN, et al. Outcome of ileal pouch after secondary diagnosis of Crohn’s disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2000;15:49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sagar PM, Dozois RR, Wolff BG. Long-term results of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:893–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richard CS, Cohen Z, Stern HS, et al. Outcome of the pelvic pouch procedure in patients with prior perianal disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:647–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgado PJ Jr, Wexner SD, James K, et al. Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: is preoperative anal manometry predictive of postoperative functional outcome? Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:224–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ziv Y, Fazio VW, Church JM, et al. Stapled ileal pouch anal anastomoses are safer than handsewn anastomoses in patients with ulcerative colitis. Am J Surg. 1996;171:320–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]