Abstract

Immune suppression associated with morbillivirus infections may influence the mortality rate by allowing secondary bacterial infections that are lethal to the host to flourish. Using an in vitro proliferation assay, we have shown that all members of the genus Morbillivirus inhibit the proliferation of a human B-lymphoblast cell line (BJAB). Proliferation of freshly isolated, stimulated bovine and caprine peripheral blood lymphocytes is also inhibited by UV-inactivated rinderpest (RPV) and peste-des-petits ruminants viruses. As for measles virus, coexpression of both the fusion and the hemagglutinin proteins of RPV is necessary and sufficient to induce immune suppression in vitro.

Morbillivirus infections induce severe disease in their natural hosts, causing high morbidity and mortality. The genus Morbillivirus and the genera Rubulavirus and Respirovirus comprise the subfamily Paramyxovirinae within the family Paramyxoviridae. Known members of the genus Morbillivirus include Measles virus (MV), Rinderpest virus (RPV), Peste-des-petits ruminants virus (PPRV), Canine distemper virus (CDV), Phocine distemper virus, Porpoise morbillivirus, and Dolphin morbillivirus (DMV) (3, 4). These morbilliviruses infect mammalian hosts, and disease is generally confined to one order of mammals; e.g., MV infects solely primates, while RPV and PPRV naturally infect only Artiodactyla (cloven-hoofed animals), and CDV naturally infects Carnivora (2).

Despite widespread use of an effective live attenuated vaccine, MV remains a major killer disease of infants in developing countries, accounting for over 1 million deaths per annum. The main cause of death is secondary bacterial infections that flourish due to MV-induced immunosuppression. Although MV is rapidly cleared from the host, lymphoproliferative responses to mitogens and recall antigens are suppressed for up to several months postinfection. Both B and T subsets of leukocytes are affected, but not the CD4+/CD8+ ratio (1). MV infection interferes with the differentiation and specialization of lymphocyte functions but does not alter those already established (11). In the case of RPV, lymphodepletion in the thymus, Peyer's patches, spleen, and pulmonary lymph nodes indicates that these infections also induce immunosuppression in infected hosts (27). Recently, we showed that cattle infected with a virulent strain of RPV also show reduced responses of leukocytes to mitogens ex vivo (15). As for MV, lung infections with bacterial secondary infection are common features of PPRV (12, 19), and morbillivirus infections in marine mammals result in a severe pulmonary distress with increased levels of opportunistic bacteria, evidence of immunosuppression in these animals (5, 6).

Many theories have been proposed to account for MV-induced nonresponsiveness of the immune system, although there is little agreement about the mechanisms involved (7, 14, 22, 23, 26). It is likely that there are many factors that contribute to immunosuppression in vivo. During the course of acute MV infection, only a small proportion of peripheral blood leukocytes are infected, indicating that indirect mechanisms, rather than the direct infection and destruction of lymphoid cells, are involved in the widespread immune unresponsiveness. Using a two-cell system, Schlender and colleagues showed that small numbers of MV-infected, UV-irradiated, lymphocyte presenter cells (PC) could inhibit the proliferation of a responder cell population (RC), either mitogen-stimulated naïve lymphocytes or human lymphocytic or monocytic cell lines, even after a short contact period (22). The effect was abolished when the two cell populations were physically separated by a semipermeable membrane, showing that soluble factors do not influence immunosuppression in this model. Coexpression of a cleaved form of the fusion (F) protein and the hemagglutinin (H) proteins of MV on the PC surface was necessary and sufficient to induce the effect, both in vitro and in a cotton rat model (17, 22). It was further shown that immune suppression in these models was due to cell cycle arrest, not apoptosis of the RC (18, 24). Over 50% of the RC were arrested between G0 and G1 of the cell cycle following cocultivation with MV-infected PC (16, 23). The remaining lymphocytes did progress through the cell cycle but at a lower rate. A study at the molecular level revealed that levels of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 remained high in nonproliferating cell populations (8). Further, there was decreased expression of cyclins D3 and E, which phosphorylate retinoblastoma protein, allowing entry of cells into the S phase of the cell cycle. Furthermore, normal upregulation of retinoblastoma protein did not occur (16).

In this paper we show that all members of the genus Morbillivirus can inhibit the in vitro proliferation of a human B-lymphoblast cell line (BJAB) following inactivation by UV-irradiation. Proliferation of freshly isolated, mitogen-stimulated bovine and caprine peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) was also inhibited by UV-inactivated RPV and PPRV. Further, using recombinant adenovirus- and capripoxvirus-expressed RPV glycoproteins, we found that coexpression of both the F and the H proteins on the PC surface was necessary and sufficient to induce immunosuppression.

All strains of morbillivirus inhibit lymphoid-cell proliferation in vitro.

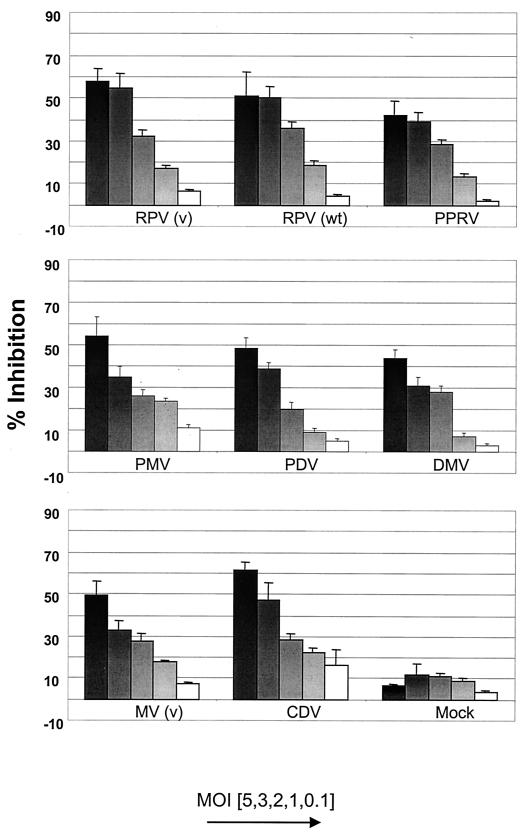

To determine whether all known morbilliviruses inhibit proliferation of lymphoid cells, an in vitro proliferation assay was carried out based on one previously described by Schlender and colleagues (22). Different amounts of UV-inactivated virus, corresponding to original multiplicities of infection (MOIs) ranging from 0.1 to 5, were mixed with BJAB cells, the RC population. All morbilliviruses used, MV (human 2), RPV wild type (Saudi/81), RPV vaccine (RBOK), PPRV vaccine (Nigeria/75/1), phocine distemper virus, porpoise morbillivirus, DMV, and CDV (Onderstepoort), were grown and titrated on Vero cells. Virus was harvested from total cell preparations by freeze-thawing and centrifugation to remove cellular debris. Viruses were then inactivated by UV-irradiation, typically for between 5 and 10 min depending on the virus. Inactivation was confirmed either by performing up to three passages on Vero cells and observing the cells for cytopathic effects for up to 7 days or by indirect immunofluorescence after 48 h (25). Inactivated virus and the RC population were incubated for 72 h, and the proliferative response was determined with a 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (13). All assays were performed in triplicate, and the results shown are the means of three independent experiments with the standard errors.

Inhibition of proliferation of the RC population increased as higher doses of UV-irradiated morbillivirus were added, from approximately 10% inhibition at an MOI of 0.1 to approximately 60% inhibition at an MOI of 5 (Fig. 1). It was previously reported that little difference could be detected in the in vitro immunosuppressive ability of wild-type and vaccine strains of MV (22). In the case of RPV, little difference was observed in the immunosuppressive ability of a wild-type (Saudi/81) and a vaccine strain (RBOK) of the virus. However, a difference cannot be totally ruled out, as only the infectious dose of each virus was standardized between preparations and not the number of virus particles or concentration of virus proteins. As a control, RC were also incubated with a Vero cell homogenate prepared and treated in the same manner as the viruses used in each assay. No significant effect on RC proliferation was observed with this control preparation. As shown for MV (22), the inhibition produced by RPV was specific to cells of lymphoid origin and not a nonspecific growth arrest due to contact with other cells, such as HeLa and Vero cells (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Effect of morbilliviruses on BJAB cell proliferation. Various amounts of UV-inactivated morbilliviruses, corresponding to original MOIs from 0.1 to 5, were mixed with BJAB cells (RC) for 72 h. Proliferation of the RC was determined by the MTT assay, and inhibition induced by the inactive virus was calculated according to the formula [(optical density at 550 nm of control cells − optical density at 550 nm of inactive virus and cells)/optical density at 550 nm of control cells] × 100.

The immunosuppressive abilities of related enveloped RNA viruses and empty capsids of foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) were also studied. Mumps virus (SBL), SV5, and vesicular stomatitis virus (New Jersey) were also grown and titrated on Vero cells and UV irradiated, as for the morbilliviruses. Virus preparations were mixed with RC at an MOI of 5, and the effects of each virus on RC proliferation were determined with the MTT assay. Whereas the vaccine strains of both RPV and MV inhibited the proliferation of BJAB cells by approximately 50%, none of the other viruses tested had a significant effect on BJAB proliferation. Reduction of proliferation was approximately 12% or less, equivalent to that seen with control Vero cell homogenate (Fig. 2A). Therefore, other RNA viruses, including other members of the Paramyxoviridae, do not produce any immunosuppression in this system. That is not to say that in vivo they do not alter immune function, but we postulate that they do not share this mechanism with the genus Morbillivirus.

FIG. 2.

Effect of other viruses and soluble factors on BJAB cell proliferation. (A) Virus preparations, excluding FMDV empty capsids, were UV inactivated and mixed at an MOI of 5 with BJAB cells for 72 h. The empty capsids of FMDV A10 were prepared in a suspension of storage buffer (0.75% ammonium persulfate, 50 mM phosphate, 20 mM Tris [pH 7.5]) at a concentration of 0.73 mg/ml. (B) A PC population was generated by infecting BJAB cells with MV (v) or RPV (v) at an MOI of 3 for 48 h. PC and uninfected BJAB cells (RC) were either mixed (−) or separated by a porous membrane (+) and incubated for 72 h. In each case, proliferation of the RC was determined as described for Fig. 1.

Soluble factors released from PC do not cause inhibition of proliferation of RC.

To determine if direct contact between the two cell populations was required to induce inhibition of proliferation or if soluble factors play a significant role, PC were generated by infecting BJAB cells with RPV (RBOK) or MV at an MOI of 5 and were separated from the RC with a 0.2-μm-pore-size semipermeable anopore membrane (Nunc). The RC were plated and the PC were added over the membrane at a 1:1 ratio so that media, but not the cell populations, could mix. After a 72-h coculture period, the proliferative response of the RC population was determined with the MTT assay. Separating the RC from the PC population decreased the inhibitory effect on proliferation from approximately 50 to 10% for vaccine strains of both MV and RPV (Fig. 2B). Our data indicate that soluble factors released from PC do not play a role in immunosuppression but rather direct contact between the two cell populations is required in this in vitro system. However, it is possible that soluble factors are released from RC after initial contact with PC, and these could also have effects on RC proliferation.

RPV and PPRV inhibit proliferation of host PBL.

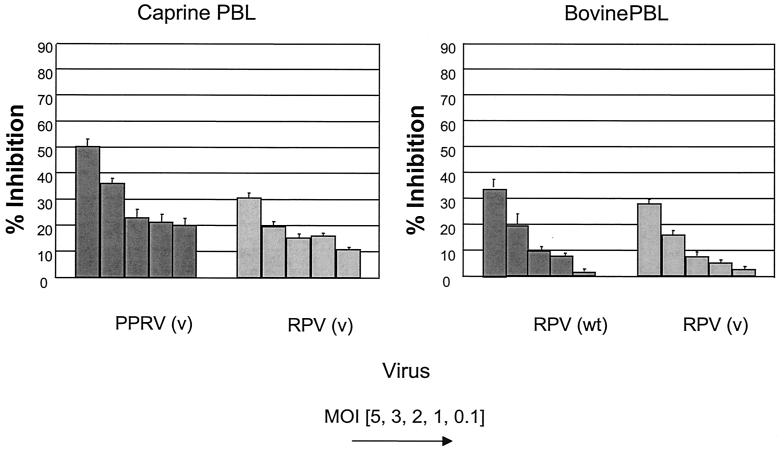

We then studied the effect of UV-inactivated virus on cells derived from the natural host of the virus. Caprine and bovine PBL were isolated and stimulated with phytohemagglutinin before being mixed with inactivated PPRV or RPV. Both PPRV and RPV inhibited proliferation of stimulated caprine PBL, and both a wild-type (Saudi/81) and a vaccine (RBOK) strain of RPV could inhibit the proliferation of stimulated bovine PBL. PPRV had a stronger immunosuppressive effect on caprine PBL than RPV, approximately 50% compared with 30% at an MOI of 5. The inhibition of bovine and caprine PBL by RPV was approximately the same (30%). There was also no significant difference between vaccine and wild-type strains of RPV in their ability to inhibit bovine PBL (Fig. 3). The degree of inhibition of PBL was not as marked as that found with BJAB cells. This may reflect the innate proliferative nature of the latter compared to mitogen-stimulated PBL. It is well documented that only a small proportion of leukocytes are infected during the course of acute measles infection (10). This mechanism of inhibition, by direct and transient contact with an infected cell, may account for the widespread nonresponsiveness of the immune system when only relatively few cells are infected.

FIG. 3.

Effect of RPV and PPRV on host PBL proliferation. Freshly isolated caprine and bovine PBL were stimulated with phytohemagglutinin and cultured with UV-inactivated PPRV and RPV vaccine strains (v) or wild-type (wt) RPV and vaccine RPV strains, respectively, at an MOI from 0.1 to 5 for 72 h. In each case, proliferation of the RC was determined with the MTT assay and inhibition was calculated as described for Fig. 1.

Coexpression of H and F glycoproteins of RPV inhibit RC proliferation.

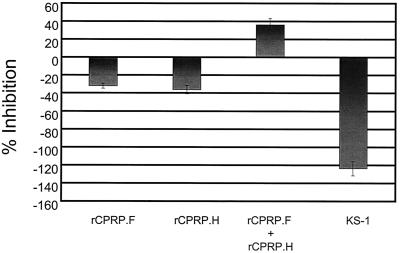

Recombinant capripoxvirus and adenovirus vectors expressing RPV proteins were used to determine the effect of individual RPV glycoproteins, or combinations of proteins, on the proliferation of the RC population. A PC population was generated by infecting BJAB cells (at MOIs of 1 for the capripoxviruses and 500 for adenoviruses) for 48 h. PC and RC (at a ratio of 1:1) were then cocultured for 72 h before inhibition of proliferation of the RC was determined. Recombinant capripoxviruses expressing RPV H (rCPRP.H) and F (rCPRP.F) proteins and the parental Kenya sheep capripoxvirus (KS-1) were grown on lamb testis cells (20, 21). PC infected with either KS-1 alone or KS-1 recombinants expressing a RPV glycoprotein on their surface had a mitogenic effect on the responder cell population. However, when the PC were coinfected with rCPRP.H and rCPRP.F, so that both RPV proteins were expressed on the cell surface, an inhibitory effect on the proliferative response of the responder cell population was observed (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Effect of capripoxvirus recombinants expressing RPV H and F proteins on BJAB cell proliferation. PC were generated by infecting BJAB cells at an MOI of 1 with RPV protein expressing recombinant capripoxviruses for 48 h. Cells were either infected singly or with both recombinant viruses. PC were mixed with uninfected BJAB cells (RC) for 72 h; then RC proliferation determined as described for Fig. 1.

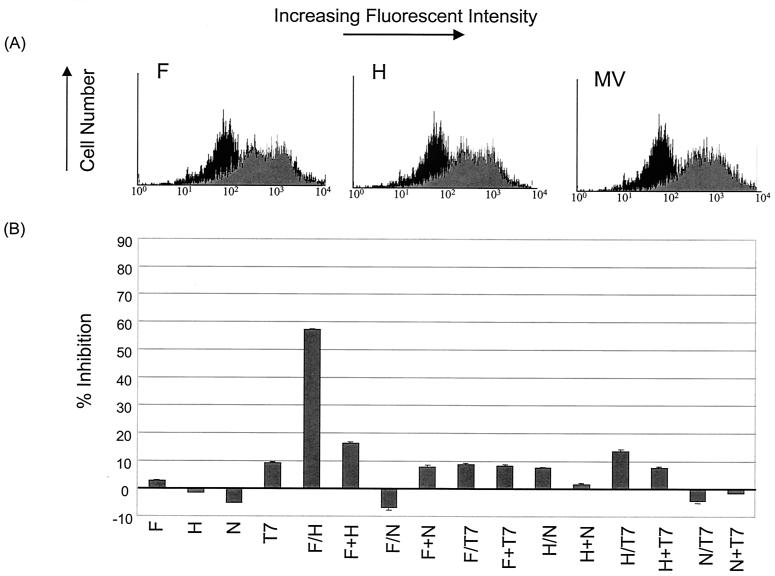

We further confirmed the role of RPV glycoproteins in immunosuppression by using recombinant adenoviruses expressing RPV proteins. Recombinant adenoviruses expressing the F, H, or N protein of RPV or the nonviral T7 protein were grown on 293 cells (15). High levels of RPV proteins, comparable to MV-infected BJAB cells, could be detected on the adenovirus-infected-cell surface by FACScan analysis (Fig. 5A). MV was used as a positive control, as it replicates to a high level in BJAB cells (this has not been established for RPV), and the polyclonal anti-RPV serum used is known to cross-react with MV. Approximately 80% of cells infected with the single H and F adenovirus constructs expressed antigen on their surface. Double expression of both H and F in cells infected with both constructs could not be absolutely determined, as a monoclonal antibody to the F protein was not available. However, at an MOI of 500, all infected cells would be expected to express both proteins. When the RPV proteins (F, H, and N) or a nonviral protein (T7) was expressed alone, inhibition was at background levels. When the PC were infected with two adenovirus recombinants, only the F and H combination of proteins showed a significant inhibitory effect on the RC proliferation. There was no evidence of fusion in this combined infection (this was also the case for the recombinant capripoxvirus system). When a PC population was generated by mixing equal numbers of cells separately expressing the different proteins, little effect on the RC proliferation was observed (Fig. 5B). These data indicated that, as for MV (22), coexpression of both RPV glycoproteins was necessary and sufficient to induce suppression of proliferation. It has been shown for MV that proliferation inhibition is independent of the presence or absence of both known virus binding receptors, SLAM and CD46 (9). Therefore, the interaction of morbillivirus H and F proteins involves some conformational change that is required to bind the as-yet-unidentified ligand responsible for initiating the process.

FIG. 5.

Effect of adenovirus recombinants expressing RPV proteins on BJAB cell proliferation. (A) The levels of expression of RPV H and F proteins were determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis using a rabbit anti-RPV hyperimmune serum. For staining, cells were first washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% fetal calf serum and 0.1% sodium azide (PBA). They were then incubated with the antibody for 45 min at 4°C, washed twice with PBA, and then incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Molecular Probes) for 45 min at 4°C. The cells were then washed and resuspended in PBA for FACScan (Becton Dickinson) analysis with Cell Quest software. (B) PC were generated by infecting BJAB cells at an MOI of 500 with RPV protein expressing recombinant adenovirus vectors for 48 h. The recombinant proteins were either expressed alone or coexpressed in pairs; e.g., where H and F were coexpressed in the same cell, the designation is H/F. Where a heterologous PC population was generated by mixing equal numbers of cells expressing only one protein, the designation is H+F. PC were mixed with uninfected BJAB cells (RC) for 72 h; then the RC proliferation was determined as described for Fig. 1.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. E. Randall (University of St. Andrews, Fife, Scotland) for providing SV5, W. Blakemore for providing the FMDV empty capsids, and A. Osterhaus (Erasmus University, Rotterdam, The Netherlands) for providing DMV. We also thank S. Schneider-Schaulies (University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany) for critically reading the manuscript and providing helpful comments.

J. Heaney was the recipient of a Department of Education for Northern Ireland studentship under the Co-operative Awards in Science and Technology scheme.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arneborn, P., and G. Biberfeld. 1983. T-lymphocyte subpopulations in relation to immunosuppression in measles and varicella. Infect. Immun. 39:29-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrett, T. 2001. Morbilliviruses: dangers old and new, p. 155-178. In G. L. Smith, J. W. McCauley, and D. J. Rowlands (ed.), New challenges to health: the threat of virus infection. Society for General Microbiology, Symposium 60. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 3.Barrett, T., I. K. G. Visser, L. Mamaev, L. Goatley, M. F. van Bressem, and A. D. M. E. Osterhaus. 1993. Dolphin and porpoise morbilliviruses are genetically distinct from phocine distemper virus. Virology 193:1010-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cosby, S. L., S. McQuaid, N. Duffy, C. Lyons, B. K. Rima, G. M. Allen, S. J. McCullough, S. Kennedy, J. A. Smyth, F. McNeilly, C. Craig, and C. Örvell. 1988. Characterisation of a seal morbillivirus. Nature 336:115-116.3185731 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Domingo, M., M. Vilafranca, J. Visa, N. Prats, A. Trudgett, and I. Visser. 1995. Evidence for chronic morbillivirus infection in the Mediterranean striped dolphin (Stenella coeruleoalba). Vet. Microbiol. 44:229-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duignan, P. J., N. Duffy, B. K. Rima, and J. R. Geraci. 1997. Comparative antibody response in harbour and grey seals naturally infected by a morbillivirus. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 55:341-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisenstein, T. K., D. Huang, J. J. Meissler, and B. Al-Ramadi. 1994. Macrophage nitric oxide mediates immunosuppression in infectious inflammation. Immunobiology 191:493-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engelking, O., L. M. Fedorov, R. Lilischkis, V. ter Meulen, and S. Schneider-Schaulies. 1999. Measles virus-induced immunosuppression in vitro is associated with deregulation of G1 cell cycle control proteins. J. Gen. Virol. 80:1599-1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erlenhoefer, C., W. J. Wurzer, S. Loffler, S. Schneider-Schaulies, V. ter Meulen, and J. Schneider-Schaulies. 2001. CD150 (SLAM) is a receptor for measles virus but is not involved in viral contact-mediated proliferation inhibition. J. Virol. 75:4499-4505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esolen, L. M., B. J. Ward, T. R. Moench, and D. E. Griffin. 1993. Infection of monocytes during measles. J. Infect. Dis. 168:47-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fugier-Vivier, I., C. Servet-Delprat, P. Rivailler, M. Rissoan, Y. Liu, and C. Rabourdin-Combe. 1997. Measles virus suppresses cell-mediated immunity by interfering with the survival and functions of dendritic and T cells. J. Exp. Med. 186:813-823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffin, D. E., and W. J. Bellini. 1996. Measles virus. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 3rd ed. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 13.Hansen, M. B., S. E. Neilsen, and K. Berg. 1989. Re-examination and further development of a precise and rapid dye method for measuring cell growth/cell kill. J. Immunol. Methods 119:203-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karp, C. L., M. Wysocka, L. M. Wahl, J. M. Ahearn, P. J. Cuomo, B. Sherry, G. Trinchieri, and D. E. Griffin. 1996. Mechanism of suppression of cell-mediated immunity by measles virus. Science 273:228-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lund, B. T., A. Tiwari, S. Galbraith, M. D. Baron, W. I. Morrison, and T. Barrett. 2000. Vaccination of cattle with attenuated rinderpest virus stimulates CD4+ T cell responses with broad viral antigen specificity. J. Gen. Virol. 81:2137-2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naniche, D., S. I. Reed, and M. B. A. Oldstone. 1999. Cell cycle arrest during measles virus infection: a Go-like block leads to suppression of retinoblastoma protein. J. Virol. 73:1894-1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niewiesk, S., I. Eisenhuth, A. Fooks, J. Christopher, S. Clegg, J. Schnorr, S. Schneider-Schaulies, and V. ter Meulen. 1997. Measles virus-induced immune suppression in the cotton rat (Sigmodon hispidus) model depends on viral glycoproteins. J. Virol. 71:7214-7219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niewiesk, S., H. Ohnimus, J. Schnorr, M. Gotzelmann, S. Schneider-Schaulies, C. Jassoy, and V. ter Meulen. 1999. Measles virus-induced immunosuppression in cotton rats is associated with cell cycle retardation in uninfected lymphocytes. J. Gen. Virol. 80:2023-2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roeder, P. L., and T. U. Obi. 1999. Recognising peste-des-petits ruminants: a field manual. FAO animal health manual 5. Food and Agriculture Organization, Rome, Italy.

- 20.Romero, C. H., T. Barrett, S. A. Evans, R. P. Kitching, P. D. Gershon, C. Bostock, and D. N. Black. 1993. Single capripoxvirus recombinant vaccine for the protection of cattle against rinderpest and lumpy skin disease. Vaccine 11:737-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Romero, C. H., T. Barrett, R. W. Chamberlain, R. P. Kitching, M. Fleming, and D. N. Black. 1994. Recombinant capripoxvirus expressing the haemagglutinin protein gene of rinderpest virus: protection of cattle against rinderpest and lumpy skin disease. Virology 204:425-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schlender, J., J. Schnorr, P. Spielhofer, T. Cathomen, R. Cattaneo, M. A. Billeter, V. ter Meulen, and S. Schneider-Schaulies. 1996. Interaction of measles virus glycoproteins with the surface of uninfected peripheral blood lymphocytes induces immunosuppression in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:13194-13199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneider-Schaulies, S., S. Niewiesk, J. Schneider-Schaulies, and V. ter Meulen. 2001. Measles virus induced immunosuppression: targets and effector mechanisms. Curr. Mol. Med. 1:163-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schnorr, J., M. Seufert, J. Schlender, J. Borst, I. C. D. Johnston, V. ter Meulen, and S. Schneider-Schaulies. 1997. Cell cycle arrest rather than apoptosis is associated with measles virus contact-mediated immunosuppression in vitro. J. Gen. Virol. 78:3217-3226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Timm, B., C. Kondor-Koch, H. Lehrach, H. Riedel, J. E. Edstrom, and H. Garoff. 1983. Expression of viral membrane proteins from cDNA by microinjection into eukaryotic cell nuclei. Methods Enzymol. 96:496-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tishon, A., M. Manchester, F. Scheiflinger, and M. B. A. Oldstone. 1996. A model of measles virus-induced immunosuppression: enhanced susceptibility of neonatal human PBLs. Nat. Med. 2:1250-1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wohlsein, P., H. M. Wamwayi, G. Trautwein, J. Pohlenz, B. Liess, and T. Barrett. 1995. Pathomorphological and immunohistological findings in cattle experimentally infected with rinderpest virus isolates of different pathogenicity. Vet. Microbiol. 44:141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]