Abstract

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), which constitute the largest and structurally best conserved family of signaling molecules, are involved in virtually all physiological processes. Crystal structures are available only for the detergent-solubilized light receptor rhodopsin. In addition, this receptor is the only GPCR for which the presumed higher order oligomeric state in native membranes has been demonstrated (Fotiadis, D., Liang, Y., Filipek, S., Saperstein, D. A., Engel, A., and Palczewski, K. (2003) Nature 421, 127–128). Here, we have determined by atomic force microscopy the organization of rhodopsin in native membranes obtained from wild-type mouse photoreceptors and opsin isolated from photoreceptors of Rpe65−/− mutant mice, which do not produce the chromophore 11-cis-retinal. The higher order organization of rhodopsin was present irrespective of the support on which the membranes were adsorbed for imaging. Rhodopsin and opsin form structural dimers that are organized in paracrystal-line arrays. The intradimeric contact is likely to involve helices IV and V, whereas contacts mainly between helices I and II and the cytoplasmic loop connecting helices V and VI facilitate the formation of rhodopsin dimer rows. Contacts between rows are on the extracellular side and involve helix I. This is the first semi-empirical model of a higher order structure of a GPCR in native membranes, and it has profound implications for the understanding of how this receptor interacts with partner proteins.

Vision is essential for the survival of many organisms ranging from unicellular dinoflagellates to man (1). Rhodopsin, the primary molecule in the visual signaling cascade, is activated by a single photon and induces subunit dissociation of transducin (Gt)1 molecules, the cognate G proteins, amplifying the light signal (2). Rhodopsin is also a prototypical G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) and a member of subfamily A, which comprises ∼90% of all GPCRs (3). GPCRs are essential proteins in signal transduction across cellular membranes (4). The first crystal structure of a GPCR, rhodopsin, has been determined (5), and two refined models have subsequently been reported (6, 7).

In vertebrate retinal photoreceptors, rod outer segment (ROS) disk membranes are tightly stacked (8). The stacking of these internal cellular membrane structures ensures a dense packing of light-absorbing rhodopsins, which constitute >90% of all disk membrane proteins, and in turn, a high probability of single photon absorption (9). In ROS disk membranes, rhodopsin occupies ∼50% of the space within the disks (8). Knockout mice lacking rhodopsin do not develop ROS, which indicates a structural role for this protein (10, 11). The organization of rhodopsin and other GPCRs in their native membranes is of paramount importance because the physiological properties of these receptors may depend on their oligomeric state (reviewed in Refs. 4 and 12-14). In native disk membranes, the existence of distinct, densely packed rows of rhodopsin dimers has been demonstrated by AFM (15).

To obtain further insight into the native molecular organization of GPCRs, we have used AFM to visualize the organization of rhodopsin and opsin in their native membranes. Finally, we produced a model of rhodopsin oligomers that accounts for all geometrical constraints imposed by AFM and crystallo-graphic data. This model shows, for the first time, the higher order organization of a GPCR in its native environment. The contact sites identified in the model, which are responsible for the oligomerization of rhodopsin, are likely to be crucial for the self-assembly of other GPCRs (4, 12-14).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of ROS and Disk Membranes—All animal experiments employed procedures approved by the University of Washington Animal Care Committee. Rpe65-deficient mice and wild-type C57BL/6 mice were obtained from M. Redmond (National Eye Institute) (16) and The Jackson Laboratory, respectively. All animals (4 – 8 weeks old) were maintained in complete darkness for >120 min before they were sacrificed. The eyes were removed and the retinas isolated in complete darkness with the aid of night vision goggles (Lambda 9, ITT Industries).

Twelve mouse retinas were placed in a tube with 120 μl of 8% OptiPrep (Nycomed, Oslo, Norway) in Ringer's buffer (130 mm NaCl, 3.6 mm KCl, 2.4 mm MgCl2, 1.2 mm CaCl2,10mm Hepes, pH 7.4, containing 0.02 mm EDTA) and vortexed for 1 min. The samples were centrifuged at 200 × g for 1 min, and the supernatant containing the ROS was removed gently. The pellet was dissolved in 120 μl of 8% OptiPrep, vortexed, and centrifuged again. The vortexing and sedimentation sequence was repeated six times. The collected ROS supernatants (∼1.5 ml) were combined, overlaid on a 10–30% continuous gradient of Opti-Prep in Ringer's buffer, and centrifuged for 50 min at 26,500 × g. ROS were harvested as a second band (about two-thirds of the way from the top), diluted three times with Ringer's buffer, and centrifuged for 3 min at 500 × g to remove the cell nuclei. The supernatant containing ROS was transferred to a new tube and centrifuged for 30 min at 26,500 × g. The pelleted material contained pure, osmotically intact ROS.

ROS were burst in 2 ml of 2 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, at 0 °C for 15 h. Disks were overlaid on a 15–40% continuous gradient of OptiPrep in Ringer's buffer. The sample was centrifuged for 50 min at 26,500 × g, and the disks were collected from a faint band located about two-thirds of the way from the top of the gradient. The harvested intact disks were then diluted three times with Ringer's solution and pelleted for 30 min at 26,500 × g.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting were performed as described previously (17).

Phosphorylation and Reduction Reactions—Phosphorylation of rhodopsin and reduction of all-trans-retinal were carried out as described previously (18). The indicated samples were sonicated for 30 s in a Bransonic 220 sonicator (Fisher).

Atomic Force Microscopy—Washed disk membranes were adsorbed to mica in 2 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, for 15–20 min and washed with 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 150 mm KCl, 25 mm MgCl2 (recording buffer). AFM experiments were performed using a Nanoscope Multimode microscope (Digital Instruments) equipped with an infrared laser head, a fluid cell, and oxide-sharpened silicon nitride cantilevers (OMCL-TR400PSA, Olympus), calibrated as described previously (19). Topographs were acquired in contact mode at minimal loading forces (≤100 piconewtons). Trace and retrace signals were recorded simultaneously at line frequencies ranging between 4.1 and 5.1 Hz. The power spectrum displayed in the inset in Fig. 4a was calculated with the SEMPER image processing system (20).

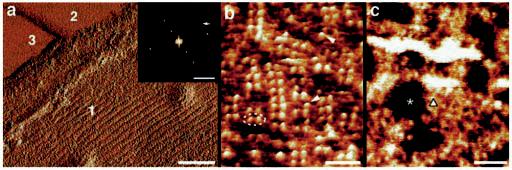

Fig. 4.

Organization of opsin in native Rpe65−/− disk membranes. a, three different surface types are discerned in the deflection image of a single-layered Rpe65−/− disk membrane: the paracrystalline, cytoplasmic surface of opsin (type 1), lipid (type 2), and mica (type 3). a, inset, calculated power spectrum of the paracrystalline region displayed in a. The first-order diffraction spot at (3.8 nm)−1 is marked by an arrow. b, the paracrystalline arrangement of opsin dimers (broken ellipse) in the native membrane. Occasional single opsin monomers are marked by arrowheads. c, the corrugated and flexible extracellular surface of opsin. The height between the lipid bilayer surface (asterisk) and clusters of opsin (triangle) is 2.8 ± 0.2 nm (n = 60). Scale bars: 50 nm (a), 5 nm−1 (a, inset), 15 nm (b), and 50 nm (c). Vertical brightness ranges: 0.3 nm (a), 1.6 nm (b), and 3.3 nm (c).

Scanning EM—The retinas without retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 0.1m cacodylate buffer, 2% sucrose, pH 7.4, for 6 h. Fixed disks were allowed to settle on the coated (1% poly-l-lysine-coated) coverslip and washed with water. All samples were washed in 0.1m cacodylate buffer, 2% sucrose, fixed with 1% OsO4 in washing buffer, dehydrated with ethanol, dried using a critical point drying method, sputter-coated with a 5–10-nm thick gold layer, and analyzed employing a JSF-6300F or an XL SFEG scanning electron microscope (FEI Sirion, Philips).

Light and Transmission EM—ROS and disks were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 1% OsO4, 0.13m sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, for 1 h, washed three times using EM rinsing buffer (0.13m NaH2PO4, 0.05% MgCl2, pH 7.4) and collected by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 3 min. ROS and disk pellets were suspended in molten 5% phosphate-buffered low-temperature gelling agarose solution, collected by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 3 min, and cooled. The ROS and disk pellets were secondarily fixed with 1% OsO4 in 0.1m phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, dehydrated with ethanol, and embedded in Eponate12 resin (Ted Pella, Inc., Redding, CA). Thin sections (1.0 μm) were cut, stained with 10% Richardson's blue solution, and subjected to light microscopy. Ultrathin sections (0.07 μm) were cut and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate solution. Samples were recorded with a Philips CM-10 EM.

Electron Microscopy of Immunogold-labeled and Negatively Stained Disk Membranes—Isolated disks were adsorbed to carbon support films mounted on electron microscopy grids, blocked with 0.5% bovine serum albumin in 150 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris, pH 7.4, and incubated for 1.5 h with 1D4 (C-terminal specificity, R. Molday) (21), 4D2 (N-terminal specificity, R. Molday) (22), C7 (C-terminal specificity, K. Palczewski), or B6-30N (N-terminal specificity, P. Hargrave) (23) anti-rhodopsin antibody at dilutions of 1:10, 1:10, 1:1000, and 1:10, respectively. A secondary antibody, goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with 15 nm gold, was used at a dilution of 1:100. Antibody-labeled and unlabeled disk membranes were stained with Nano-W negative stain (Nanoprobes, Stony Brook, NY) or 0.75% uranyl acetate, respectively. Electron micrographs were recorded with a Philips CM-10 or a Hitachi H-7000 electron microscope. The power spectra displayed in Fig. 5 were calculated with the SEMPER image processing system (20).

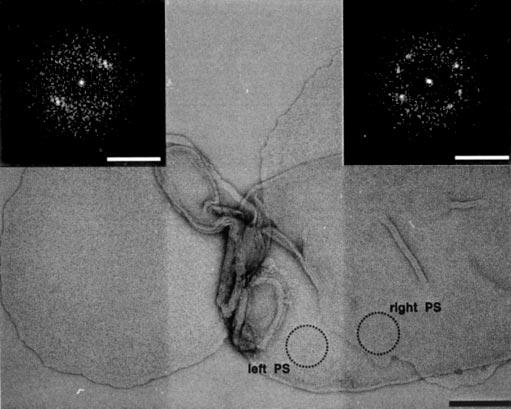

Fig. 5.

Electron microscopy of negatively stained native disk membranes adsorbed on carbon film. Power spectra were calculated from a circular region adsorbed directly to the carbon film (left inset) and from another one lying on a disk membrane (right inset). Both diffraction patterns document crystallinity irrespective of the support. Scale bars: 150 and 2.5 nm−1 (left and right insets, respectively).

Modeling—A monomer of the rhodopsin crystal structure (Protein Data Bank code 1HZH) (6) was used to build an oligomeric model of rhodopsin in the lipid membrane. The loops not present in the rhodopsin crystal structure were created using the Modeler module (24) of Insight II (Insight II, version 2000, Accelrys, San Diego). Verification of the created loops and of the whole structure was accomplished with the Profile-3D module (25) by evaluating the compatibility between sequence and structure. The MOLMOL program was used to analyze the modeled macromolecular structures (26). This theoretical model of the native rhodopsin organization was deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession number 1N3M.

RESULTS

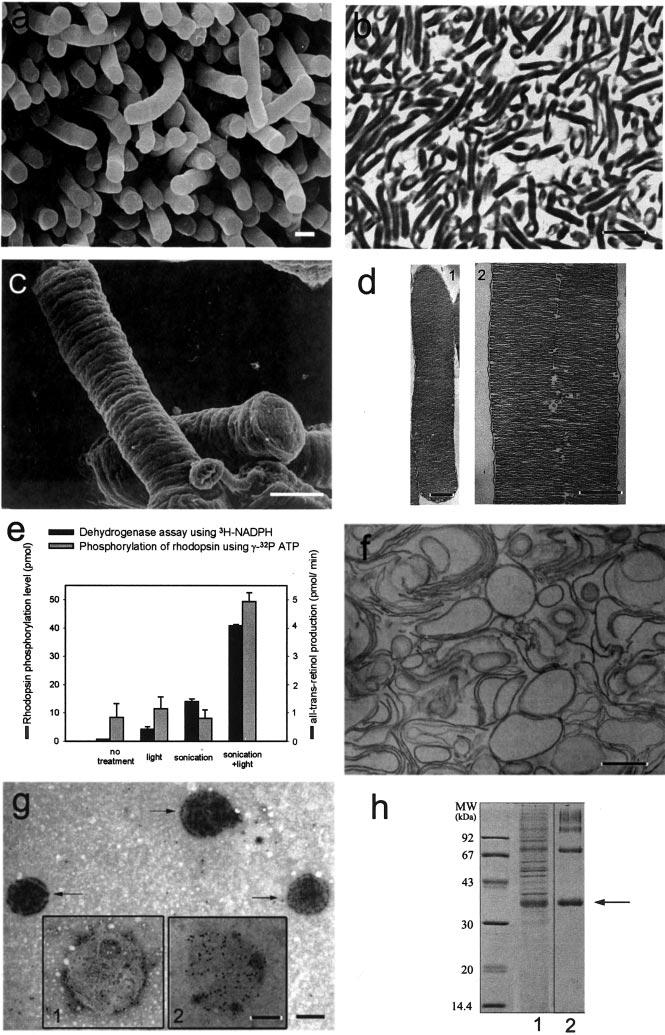

Isolation and Characterization of ROS and Disk Membranes—ROS were isolated from mouse retinae. As demonstrated by transmission EM, scanning electron, and light microscopy, the protocol employed yielded highly enriched and structurally preserved ROS with a diameter of 0.85–1.4 μm and a length of 6–10 μm (Fig. 1). Thus, the diameters of ROS still attached to the retina (Fig. 1a) and isolated ROS (Fig. 1, b–d) were comparable, suggesting structural integrity. Moreover, to check the quality of our preparations, we employed UV-visible spectroscopy and enzymatic assays of rhodopsin phosphorylation using intracellular endogenous rhodopsin kinase (18) and reduction of the photoisomerized chromophore of rhodopsin (27), all-trans-retinal, using membrane impermeable [γ-32P]ATP and [C4-3H]NADPH, respectively (Fig. 1e). The phosphorylation level was low (8.40 pmol) in untreated samples. Samples that were irradiated by light and subsequently sonicated expressed low quantities of phosphorylated rhodopsin as well. In contrast, the phosphorylation was the highest (49.40 pmol) in samples that were sonicated during light irradiation. The amount of [3H]retinol was lowest in untreated samples and remained low in samples that were sonicated after light irradiation. In samples sonicated under light irradiation, the quantity of [3H]retinol was the highest (Fig. 1e). Thus, the results indicated that the isolated ROS were osmotically intact and that the rhodopsin molecules were fully active.

Fig. 1.

Isolation and characterization of mouse ROS. a, scanning electron micrograph of mouse ROS attached to the retina. b, light micrograph of isolated ROS indicating the purity of the preparation. c, scanning electron micrograph of isolated ROS. d, transmission electron micrographs of lower and higher magnifications of isolated sectioned ROS. Disks are arranged in a stack and are surrounded by the plasma membrane (panel 1). An incisure running through the ROS can be discerned at a higher magnification (panel 2). Each disk has cytoplasmic and extracellular (intradiscal) surfaces and a rim region that joins the two layers of the bilayer. e, permeability of ROS as tested using phosphorylation of rhodopsin and redox reactions. The gray bars show the assays of rhodopsin phosphorylation of intact ROS under different conditions. The black bars represent the dehydrogenase assays using [C4-3H]NADPH under different conditions. f, electron micrograph of isolated disks prepared by thin sectioning. Isolated disks appeared as vesicles. g, electron microscopy of immunogold-labeled and negatively stained isolated disks. The arrows indicate native disks exposing the cytoplasmic surface, which is labeled with the 1D4 antibody specific toward the C terminus of rhodopsin. Inset 1, membrane from burst disk exposing the extracellular surface and incubated with antibody 1D4. Gold particles are observed at the periphery of the disk. Inset 2, same as inset 1 but incubated with antibody 4D2 against the N terminus of rhodopsin. Gold particles are evenly distributed on the extracellular surface of the disk. h, Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel of isolated ROS (lane 1) and isolated disks (lane 2). Rhodopsin is found predominantly as a monomer (arrow) but also as a multimer (lane 2). Scale bars: 1 μm (a), 6 μm (b), 1 μm (c), 0.5 μm (d, 1), 0.3 μm (d, 2), 0.6 μm (f and g), and 0.3 μm (insets in g).

Disks isolated after osmotic bursting of the ROS and prepared by thin sectioning appeared as vesicles in the EM, compatible with the high osmotic pressure expected to inflate the structurally preserved disks (Fig. 1f). Immunogold labeling of disks was performed using antibodies directed against the N-terminal (4D2 antibody) and C-terminal (1D4 antibody) ends of rhodopsin. More than 90% of the disks bound the C-terminal anti-rhodopsin antibody throughout the disk surface (Fig. 1g, arrows). Less than 10% were labeled around their rim (Fig. 1g, inset 1), suggesting that disrupted disks expose their extracellular surface. In agreement, about 10% of the disks were labeled when using the antibody directed against the rhodopsin N terminus (Fig. 1g, inset 2). Taken together, the antibody labeling experiments strongly support the structural preservation of the disk membranes during their isolation. SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1h) revealed that the disk preparation did not contain significant amounts of soluble proteins normally present in ROS and was enriched in rhodopsin (>95%). The latter finding was identified by immunoblotting using the 4D2 and C7 antibodies (data not shown).

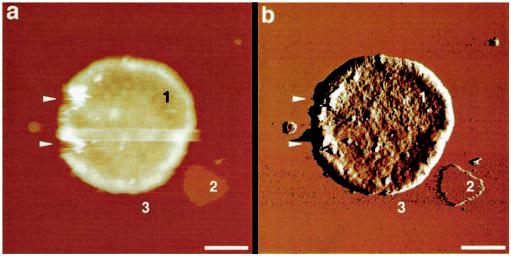

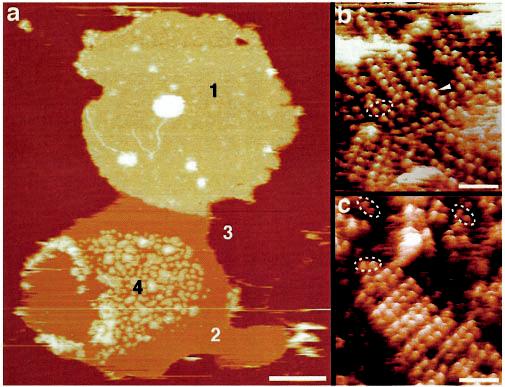

AFM Imaging of Rhodopsin in Native Disk Membranes—To unveil the native supramolecular arrangement of rhodopsin, isolated disk membranes were adsorbed to freshly cleaved mica and imaged by AFM in buffer solution. The AFM was equipped with an infrared laser to avoid the formation of opsin, the retinal-depleted form of rhodopsin (28). The morphology of an intact native disk adsorbed to mica is revealed in Fig. 2. Three different surface types are evident: the cytoplasmic side of the disk (type 1), co-isolated lipid (type 2), and mica (type 3). Bare lipid bilayers had a thickness of 3.7 ± 0.2 nm (n = 86) and an unstructured topography (Fig. 2, type 2). Compared with the topography of the lipid, the cytoplasmic surface (type 1) of the disk was highly corrugated, indicating the presence of densely packed proteins (see deflection image in Fig. 2b). Well adsorbed, single- and double-layered disk membranes had a thickness of 7–8 nm and 16–17 nm, respectively, a circular shape, and diameters between 0.9 and 1.5 μm. These disk diameters, determined by AFM, are in excellent agreement with those obtained from ROS by scanning electron microscopy (Fig. 1, a and c) and light and electron microscopy (Fig. 1, b–d). Open, spread-flattened disks adsorbed as round-shaped single-layered membranes to mica and exhibited four different surface types (Fig. 3). The first surface type (Fig. 3a, type 1) was characterized by a highly textured topography consisting of densely packed double rows of protrusions forming paracrystals (Fig. 3b). SDS-PAGE revealed that rhodopsin was present at a high concentration in such disk membrane preparations (Fig. 1h), suggesting that the visualized densely packed rows and paracrystals are related to this major protein. The second and third surface types were the same as in Fig. 2, i.e. lipid and mica. The fourth surface type (Fig. 3a, type 4, and Fig. 3c) had the same morphology as the first except that the paracrystals formed rafts of rhodopsin separated by lipid. At higher magnification, rhodopsin dimers from densely packed regions (Fig. 3b, broken ellipses) or raft-like cluster (Fig. 3c, broken ellipses) to break off the rows were seen, identifying them as the building blocks of the paracrystals. Occasionally, single rhodopsin monomers (Fig. 3b, arrowhead) were detected on such topographs. The packing density in surface type 1 areas ranged between 30,000 and 55,000 rhodopsin monomers/μm2 (15), similar to the packing density within the rhodopsin islands in surface type 4 areas (in Fig. 3c the packing density is about 34,000 rhodopsin monomers/μm2). Obviously, the overall packing density of rhodopsin measured by AFM on tightly packed regions (Fig. 3b) or within rhodopsin rafts (Fig. 3c) is higher than that measured by optical methods (29).

Fig. 2.

Morphology of intact native disks adsorbed to mica and imaged in buffer solution. Shown are height (a) and deflection (b) images of an intact disk membrane having a typical thickness of 16–17 nm. Three different surface types are evident: the cytoplasmic surface of the disk (type 1), co-isolated lipid (type 2), and mica (type 3). The deflection image (b) reveals that surface type 1 is rough compared with bare lipid (type 2), indicating the presence of densely packed proteins. The arrowheads mark defects introduced by the AFM tip during scanning. Scale bars: 250 nm (a and b). Vertical brightness ranges: 60 nm (a) and 0.6 nm (b).

Fig. 3.

Topography of an open, spread-flattened disk adsorbed to mica and imaged in buffer solution. a, height image of the open, spread-flattened disk. Four different surface types are evident: the cytoplasmic surface of the disk (types 1 and 4), lipid (type 2), and mica (type 3). The topographies of regions 1 (b) and 4 (c) at higher magnification reveal densely packed rows of rhodopsin dimers. Besides paracrystals, single rhodopsin dimers (broken ellipses) and occasional rhodopsin monomers (arrowhead) are discerned floating in the lipid bilayer. Scale bars: 250 nm (a) and 15 nm (b and c). Vertical brightness ranges: 22 nm (a) and 2.0 nm (b and c).

AFM Imaging of Opsin in Native Disk Membranes—The 65-kDa protein RPE65 is highly expressed in RPE cells and is one of the proteins involved in retinoid processing (reviewed in Ref. 28). In Rpe65−/− mice, retinoid analyses revealed no detectable 11-cis-products in any of the ester, aldehyde, or alcohol forms (16). Although these mice are able to develop ROS, the ROS contain opsin instead of rhodopsin. We used preparations of disks from Rpe65−/− mice to compare the structure and the native supramolecular arrangement of opsin with that of rhodopsin.

In general, the morphology of the Rpe65−/− disk membranes was similar to that of the wild-type membranes (see Fig. 3), but occasionally, even better ordered paracrystals could be found in Rpe65−/− preparations (Fig. 4a). From such areas, power spectra (Fig. 4a, inset) were calculated and the unit cell parameters determined (a = 8.4 ± 0.3 nm, b = 3.8 ± 0.2 nm, γ = 85 ± 2° (n = 9)), these values being the same as those found for wild-type paracrystals (15). At higher magnification, rows of opsin dimers forming the paracrystal (Fig. 4b, broken ellipse) were visualized, indicating the same oligomeric state as rhodopsin in its native environment (compare Fig. 4b with Fig. 3, b and c, and with Ref. 15). Occasionally, single-opsin monomers (Fig. 4b, arrowheads) were seen in such topographs. As with rhodopsin (15), opsin protruded by 1.4 ± 0.2 nm (n = 32) out of the lipid moiety on the cytoplasmic surface.

On the extracellular surface, no opsin paracrystals were evident (Fig. 4c). The surface was corrugated, irregular, and flexible, preventing the acquisition of highly resolved AFM topographs such as required to reveal the paracrystalline packing. Opsin clusters (Fig. 4c, triangle) protruded 2.8 ± 0.2 nm (n = 60) out of the lipid bilayer (Fig. 4c, asterisk) on the extracellular side, which is twice the height of the cytoplasmic protrusions. The latter finding is also in line with the atomic structure of rhodopsin determined by x-ray crystallography (6). Irregular and flexible surfaces are typical for glycosylated proteins and proteins with long, flexible termini or loops. This observation, along with the fact that opsin has a long N terminus and is glycosylated on the extracellular surface, strengthens the assignment of this surface as the extracellular side of disk membranes. Similar difficulties were encountered with the glycosylated aquaporin-1 and the His-tagged AqpZ proteins where oligosaccharides or long termini impeded the acquisition of highly resolved surface topographs by AFM (30, 31). Similar observations were also made for the membranes containing rhodopsin instead of opsin (data not shown).

EM of Native Disk Membranes—To exclude the possibility of rhodopsin paracrystal formation upon adsorption on mica, native disk membranes were adsorbed on carbon-coated electron microscopy grids, negatively stained, and investigated by EM (Fig. 5). Power spectra were calculated from different regions of the adsorbed disks. Both the power spectra from a circular region adsorbed directly to the carbon film (Fig. 5, left PS) and from another region lying on disk membranes (Fig. 5, right PS) indicated diffraction patterns documenting the crystallinity of the disks irrespective of the support.

Higher Order Organization of Rhodopsin in Native Membranes—The topographic information from AFM suggests a different packing arrangement of native rhodopsin dimers than of dimers observed in the three-dimensional crystal (5). The thickness of single-layered disk membranes, 7.8 nm (15), is compatible with the long axis, 7.5 nm, of the rhodopsin envelope derived from the 2.8-Å x-ray structure (6). This indicates that all rhodopsin molecules are integrated with their long axes perpendicular to the bilayer. The extracellular protrusion measured by AFM, 2.8 nm, is compatible with that estimated from the x-ray structure, 2.7 nm. However, the measured cytoplasmic protrusions of rhodopsin and of opsin, 1.4 nm, are significantly smaller than the 1.8 nm estimated from the atomic model.

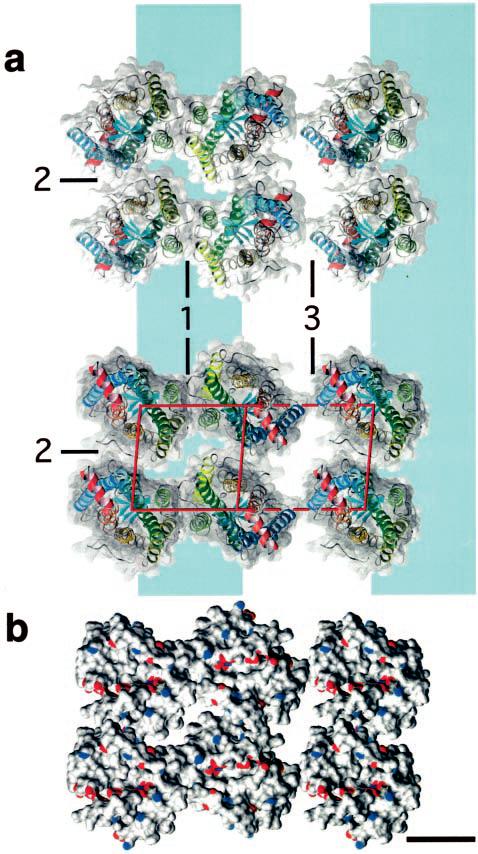

Unit cell dimensions (a = 8.4 nm, b = 3.8 nm, γ = 85°) of native rhodopsin and opsin paracrystals impose stringent boundary conditions for the packing arrangement of the rhodopsin/opsin dimers. The corresponding surface area (31.8 nm2) barely suffices to house two rhodopsin molecules whose cross-section fits in a rectangle of 4.8 × 3.7 nm2 (6). Thus, a small number of packing models emerged that were thoroughly tested for steric clashes and natures of contacts. The best model revealing the different intra- and interdimeric contacts is shown in Fig. 6a. The largest area of contact is 578 Å2 and intuitively represents the strongest interaction between rhodopsin molecules. It is found between helices IV and V, indicating this as the intradimeric contact (Fig. 6a, contact 1). Contacts involving helices I and II and the cytoplasmic loop between helices V and VI exhibit an area of 333 Å2 (Fig. 6a, contact 2) and represent the intra-row contacts. Finally, rows are weakly held together by interactions between regions of helix I close to the extracellular surface (Fig. 6a, contact 3) with a contact area of 146 Å2.

Fig. 6.

Model for the packing arrangement of rhodopsin molecules within the paracrystalline arrays in native disk membranes. a, rhodopsin assembles into dimers through a contact provided by helices IV and V (contact 1). Dimers form rows (highlighted by a blue band) as a result of contacts between the cytoplasmic loop connecting helices V and VI and helices I and II from the adjacent dimer (contact 2). Rows assemble into paracrystals through extracellular contacts formed by helix I (contact 3). Only half of the second row is shown. Views: extracellular (top panel) and cytoplasmic (bottom panel) sides of rhodopsin. Helices of rhodopsin are colored as shown: helix I in blue, helix II in light blue, helix III in green, helix IV in light green, helix V in yellow, helix VI in orange, and helix VII and cytoplasmic helix 8 in red. b, surface of rhodopsin molecules showing the locations of charged Glu and Asp (red) and Arg and Lys (blue) residues. A single line of negative charges is located close to the long groove on the cytoplasmic surface of the rhodopsin dimer. Scale bar = 2.5 nm.

Interactions within the Rho1–Rho2 dimer structure are located on both the cytoplasmic and the extracellular side. In the cytoplasmic part, hydrogen bonds dominate. These interactions include (Rho1 Arg147)–(Rho2)Asn145 and, symmetrically, (Rho1)Asn145–(Rho2)Arg147, which are located in the cytoplasmic loop between helices III and IV (C-II). Steric clashes are observed neither between the flat walls formed by helices IV and V nor between the C-II loops. In the extracellular region, the two Asn199 located at the end of helix V are within an appropriate distance from each other to form a hydrogen bond (atomic coordinates were deposited with Protein Data Bank accession number 1N3M). There is also one strong hydrophobic interaction near this site between the two Trp175 residues located in the loop between helices IV and V (E-II) in Rho1 and Rho2.

Interactions between dimers are formed only on the cytoplasmic side. They are mainly hydrophilic with hydrogen bonds between Lys339 (C-terminal) and Gln236 (C-III) and between Thr340 (C-terminal) and Gln238 (C-III). There is also a potential ionic bond in the membrane between Glu150 (C-II) and Lys231 (C-III). Interestingly, a line of positive residues spanning rhodopsin molecules as well as another line of negative side chains running across the rhodopsin oligomer are observed at the cytoplasmic surface (Fig. 6b).

DISCUSSION

For the first time, native ROS disk membranes from wild-type (this work and Ref. 15) and Rpe65-deficient mice have been imaged at sufficient resolution to reveal individual rhodopsin and opsin molecules. The distinct, densely packed double rows clearly demonstrate the dimeric nature of the native rhodopsin and opsin protein, supporting previous biochemical and pharmacological analyses that proposed GPCR dimerization and higher oligomerization (14). In contrast to indirect evidence (14) and evolutionary trace analysis (32), the AFM topographs presented here show the rhodopsin and opsin dimers directly.

A major challenge in all these experiments is the proof that the disk membranes are indeed in their native state. We have used freshly isolated, fully functional intact murine disks (Fig. 2) that were characterized by biophysical and biochemical methods (illustrated by Fig. 1). The size and shape of single-layered disk membranes (Fig. 3) adsorbed to mica after osmotic bursting were compatible with those of double-layered, intact disks (Fig. 2) imaged with the AFM. Often, single-layered disks exposing their cytoplasmic surface reveal densely packed rows of rhodopsin or opsin dimers. Interestingly, raft-like clusters of rhodopsin dimer rows floating freely in the bilayer were also observed (Fig. 3a, region 4, and Fig. 3c), compatible with recent reports on the localization of rhodopsin in lipid rafts (33, 34).

Native disk membranes adsorb similarly to EM grids or mica, both preparations revealing paracrystalline packing of rhodopsin (Figs. 3-5). Thus, the paracrystalline packing was independent of the support, i.e. mica, carbon film, and another disk membrane, which excludes the possibility that mica may induce crystallization of rhodopsin. Finally, it is important to note that grid and mica preparations and AFM observations were performed at room temperature, which precludes a possible induction of paracrystals by lipid phase transitions.

Molecular Model of Rhodopsin in Native Disks—The AFM is a remarkable instrument; it not only allows imaging of biomolecules in buffer solutions, but it also provides images of superb clarity exhibiting a vertical resolution of ±2 Å or better. When calibrated with the EM, lateral dimensions measured in AFM topographs are accurate to ±2 Å as well. Therefore, the unit cell dimensions reported by us impose stringent boundary conditions for the packing arrangement of the rhodopsin dimers.

The packing model of rhodopsin dimers and higher oligomers shown in Fig. 6a is compatible with all data currently available. In particular, a similar packing of rhodopsin has been observed in two-dimensional crystals produced by detergent treatment of native frog disk membranes (35). The general configuration of higher order rhodopsin oligomers is also in excellent agreement with the contact areas derived from the packing model. The weakest interactions are between dimer rows (Fig. 6a, contact 3), which occur at different azimuthal orientations (Fig. 3b and Ref. 15). This interaction is the result of a small contact area (146 Å2) at the extracellular end of helix I (Fig. 6a, contact 3). Rows often accommodate 10 –30 dimers and are rather straight, indicating an inherent stiffness, which is compatible with the extended contacts formed between rhodopsin dimers assembled into a row. This contact exhibits a surface area of 333 Å2 (Fig. 6a, contact 2) and involves helices I and II as well as the cytoplasmic loop between helices V and VI. The putative stiffness of rhodopsin dimer rows may explain the planar configuration and stability of disk membranes. The strongest interaction, encompassing a contact area of 578 Å2 formed by helices IV and V (Fig. 6a, contact 1), is between the monomers of the rhodopsin dimer. This is documented by dimers that are broken off from rows (Fig. 3c, broken ellipses, and Ref. 15). Additional support for this model is given by the recent finding of Guo et al. (36), who reported that helix IV is involved in the interface of dopamine D2 receptor homodimers; this is a receptor from the same GPCR subfamily as rhodopsin.

Interestingly, the contact area within the rhodopsin dimer in the asymmetric unit of the three-dimensional crystal is 1697 Å2, suggesting a much stronger intradimeric interaction than in the native case. However, the rhodopsin molecules are flipped by ∼170° in relation to each other, and their interaction is stabilized by the palmitoyl moieties. Yet this nonphysiological conformation (37) is not stable because irradiation by light induces immediate disassembly of the three-dimensional crystal (38), whereas the morphology of native disk membranes does not change after irradiation.

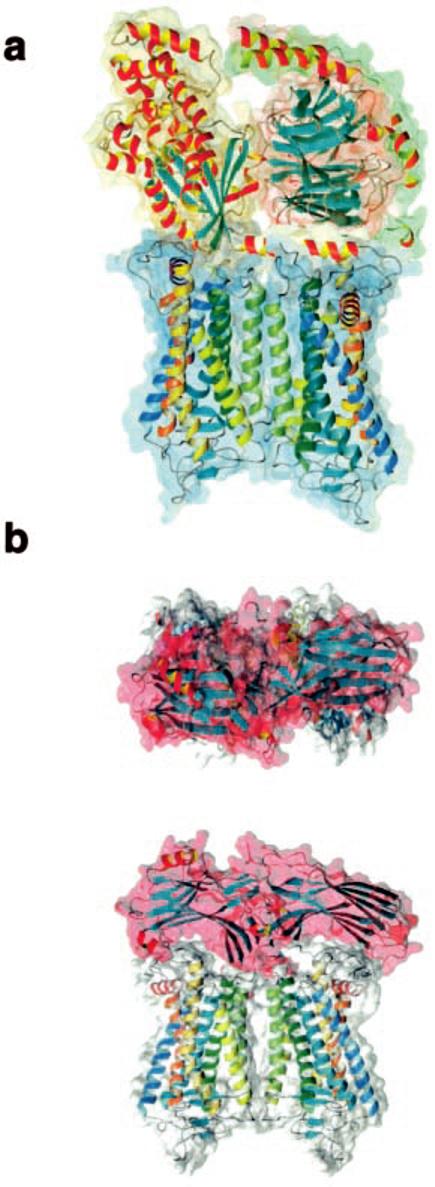

Interaction of Rhodopsin with Arrestin and Gt—The interaction of photoactivated rhodopsin with Gt encounters two conceptual problems: (i) the size of the cytoplasmic surface of rhodopsin is too small to anchor both the α- and βγ-subunits (39), and (ii) cooperativity for this interaction has been observed (40). A simple model of a 1:1 rhodopsin-Gt interaction is not compatible with these observations, whereas the dimer provides a platform (Fig. 7a) that can anchor both the α- and βγ-subunits of transducin (41), compatible with the cooperativity of this interaction, which exhibits a Hill coefficient of ∼2 (40, 42).

Fig. 7.

Model of the Gt- and arrestin-rhodopsin dimer complexes. a, theoretical model of the Gt-rhodopsin dimer complex. Helices of rhodopsin are colored as in Fig. 6. Gt is represented in a yellow space-filled background for the α-subunit, in red for the β-subunit, and in green for the γ-subunit. No optimization of the structure was carried out. b, the theoretical model reflects the interaction of one arrestin molecule with the rhodopsin dimer. The rhodopsin dimer is shown as in a, and the complex is shown from a top and side view. The secondary structures of Gt and arrestin are shown in the default colors of MolMol (26), with helices in yellow-red and β-strands in cyan.

Arrestin, another GPCR-binding protein, has a bipartite structure of two structurally homologous seven-stranded β-sandwiches, forming two putative rhodopsin binding grooves that are also separated by 3.8 nm (43, 44). The positive charge arrangement on the surface of the rhodopsin dimer matches the negative charges on arrestin. Thus, one arrestin monomer is likely to bind one rhodopsin dimer, desensitizing two rhodopsin molecules by preventing them from interacting with G proteins (Fig. 7b). This would lower the efficiency of ROS in Gt activation at higher bleaches, where bleaching of a fraction of rhodopsin would inactivate twice as many rhodopsin molecules, therefore contributing to light/dark adaptation by hindering a fraction of rhodopsin from activating Gt. At low bleaches, this mechanism would be irrelevant, because the probability of capturing photons by already capped rhodopsin would be exceedingly low.

Rhodopsin Density and Mobility—Recent observations suggest that the regulation of GPCRs and their interaction with G proteins depend on their oligomeric state (4, 12-14). Notwithstanding the reported propensity of rhodopsin (45, 46) or cone pigment (47) to oligomerize, lateral (29, 48) and rotational (49) diffusion measurements suggesting the monomeric state of rhodopsin have remained hallmarks for many decades of vision research (50). Progress in the use of the AFM has encouraged us to re-inspect the arrangement of rhodopsin molecules in native disk membranes.

Previous measurements on amphibian rod outer segments indicated a density of 25,000–30,000 rhodopsin molecules/μm2 (29). We have counted 30,000–55,000 rhodopsin molecules/μm2 in murine disk membranes visualized by AFM (15). As illustrated in Fig. 3, rhodopsin is also found in the paracrystalline rafts that float freely in the lipid bilayer. This packing form of rhodopsin exhibits a significantly lower average density than that measured on sheets of the surface type 1 shown in Fig. 3a. Therefore, our packing density data are indeed compatible with previous optical measurements (29). In contrast, the clear picture of rhodopsin dimers provided by AFM contradicts the translational and rotational diffusion measurements (48, 49). These experiments were accomplished early in the structural analysis of the disk membranes and were not designed to answer the question of the oligomeric state of rhodopsin. Also, low angle x-ray (51, 52) and neutron scattering experiments (53, 54) have not revealed the presence of rhodopsin dimers.

It has been suggested that the visual response requires a high lateral mobility of rhodopsin. This would not be achieved with the packing arrangements observed, i.e. densely packed paracrystalline arrays or paracrystalline rafts floating in the bilayer. However, the diffusion constant of transducin has been measured indirectly to be at least 0.8 μm2/s (55). This, together with the high amounts of transducin in photoreceptor cells (50, 56), suffices to explain the experimentally determined response time to a visual stimulus. Therefore, it might be appropriate to reconsider early models describing the visual signaling cascade.

Rhodopsin Density and Visual Perception—From the average packing density (15) and the molar extinction coefficient of rhodopsin (40,600 m−1 cm−1 (57)), the number of disks required in a ROS to ensure the certain capture of a photon is ∼1,200. Mature mouse ROS exhibit a length of 6–10 μm and contain 300–500 disks, suggesting that almost 40% of all photons arriving at the retina are absorbed. As the cis to trans photoisomerization of 11-cis-retinal occurs with a quantum yield of 0.67 (reviewed in Ref. 37), and because each photoisomerization event generates a detectable electric signal (9), the mouse is able to detect single photons with a probability of 25%. Animals living at low light levels, such as deep-sea fish, have optimized light detection by growing either several photoreceptor cells with short ROS or a single layer of cells with long ROS capable of capturing all incident photons (58). Thus, photodetectors designed by nature have been optimized through evolution to enhance vision and to allow a high density packing of the receptor in the disk membranes to ensure highly efficient photon absorption (59). The combined sensitivity, resolution, and adaptation range of these systems far exceeds those of the best man-made devices.

Rhodopsin Packing and Retinal Diseases—More than a hundred mutations of rhodopsin have been identified that are associated with an autosomal dominant form of retinitis pigmentosa (see the positions of mutations in Ref. 59). Some of these mutations display gain of function, such as constitutive activity, or are deficient in vectorial transport. We postulate that many of the remaining mutations (∼20% of the total amino acid substitutions) may induce disruption of the paracrystalline organization of rhodopsin and opsin, leading to malformation of the disk membrane. With the possibility of genetic manipulation in mouse models of retinitis pigmentosa, AFM analysis lends itself to many important assays to be considered in future studies. In addition, our analysis reveals that the organization of opsin in native disk membranes isolated from Rpe65−/− mice are similar, if not identical, to those from wild-type mice, therefore raising the hope that pharmacological intervention may restore proper function of defects associated with this form of Leber congenital amaurosis (60).

In summary, our study underscores the importance of rhodopsin and opsin packing and the formation of a higher order organization of these molecules in disk membranes. Dimerization has been shown to critically influence the efficacy of agonists and antagonists (4, 12-14). Because rhodopsin is the best studied member of the physiologically and pharmacologically important GPCR family, the observed organization of rhodopsin and opsin has multiple implications not only for vision but also for other signal transduction systems.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. P. Hargrave and R. Molday for the anti-rhodopsin antibody and Dr. M. Redmond for the Rpe65−/− mice. We also thank Dr. G.-F. Jang for carrying out the dehydrogenase assay and Dr. T. Maeda for the kinase assay. We are indebted to Dr. S. A. Müller for inspiring discussions and to Yunie Kim for help with the manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

This research was supported in part by United States Public Health Service Grants EY13726, EY01730, and EY08061 from NEI, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, a Foundation Fighting Blindness career development award, an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc., New York, NY, to the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Washington, a grant from James and Jayne Lea, and a grant from the E. K. Bishop Foundation. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 1N3M) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

The abbreviations used are: Gt, transducin (rod photoreceptor G-protein); AFM, atomic force microscope/microscopy; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor; ROS, rod outer segment(s); EM, electron microscopy; RPE cells, retinal pigment epithelial cells.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gehring WJ. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2002;46:65–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stryer L. Biopolymers. 1985;24:29–47. doi: 10.1002/bip.360240105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballesteros J, Palczewski K. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Dev. 2001;4:561–574. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierce KL, Premont RT, Lefkowitz RJ. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;3:639–650. doi: 10.1038/nrm908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palczewski K, Kumasaka T, Hori T, Behnke CA, Motoshima H, Fox BA, Le Trong I, Teller DC, Okada T, Stenkamp RE, Yamamoto M, Miyano M. Science. 2000;289:739–745. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teller DC, Okada T, Behnke CA, Palczewski K, Stenkamp RE. Biochemistry. 2001;40:7761–7772. doi: 10.1021/bi0155091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okada T, Fujiyoshi Y, Silow M, Navarro J, Landau EM, Shichida Y. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:5982–5987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082666399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molday RS. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1998;39:2491–2513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baylor DA, Lamb TD, Yau KW. J. Physiol. 1979;288:613–634. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lem J, Krasnoperova NV, Calvert PD, Kosaras B, Cameron DA, Nicolo M, Makino CL, Sidman RL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:736–741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Humphries MM, Rancourt D, Farrar GJ, Kenna P, Hazel M, Bush RA, Sieving PA, Sheils DM, McNally N, Creighton P, Erven A, Boros A, Gulya K, Capecchi MR, Humphries P. Nat. Genet. 1997;15:216–219. doi: 10.1038/ng0297-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.George SR, O'Dowd BF, Lee SP. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2002;1:808–820. doi: 10.1038/nrd913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bouvier M. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;2:274–286. doi: 10.1038/35067575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rios CD, Jordan BA, Gomes I, Devi LA. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001;92:71–87. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fotiadis D, Liang Y, Filipek S, Saperstein DA, Engel A, Palczewski K. Nature. 2003;421:127–128. doi: 10.1038/421127a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Redmond TM, Yu S, Lee E, Bok D, Hamasaki D, Chen N, Goletz P, Ma JX, Crouch RK, Pfeifer K. Nat. Genet. 1998;20:344–351. doi: 10.1038/3813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohguro H, Chiba S, Igarashi Y, Matsumoto H, Akino T, Palczewski K. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:3241–3245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palczewski K, McDowell JH, Hargrave PA. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:14067–14073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Müller DJ, Engel A. Biophys. J. 1997;73:1633–1644. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78195-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saxton WO. J. Struct. Biol. 1996;116:230–236. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacKenzie D, Arendt A, Hargrave P, McDowell JH, Molday RS. Biochemistry. 1984;23:6544–6549. doi: 10.1021/bi00321a041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laird DW, Molday RS. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1988;29:419–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adamus G, Zam ZS, Arendt A, Palczewski K, McDowell JH, Hargrave PA. Vision Res. 1991;31:17–31. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(91)90069-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sali A, Potterton L, Yuan F, van Vlijmen H, Karplus M. Proteins. 1995;23:318–326. doi: 10.1002/prot.340230306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bowie JU, Luthy R, Eisenberg D. Science. 1991;253:164–170. doi: 10.1126/science.1853201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koradi R, Billeter M, Wuthrich K.J. Mol. Graph 19961451–55.29–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palczewski K, Jager S, Buczylko J, Crouch RK, Bredberg DL, Hofmann KP, Asson-Batres MA, Saari JC. Biochemistry. 1994;33:13741–13750. doi: 10.1021/bi00250a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McBee JK, Palczewski K, Baehr W, Pepperberg DR. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2001;20:469–529. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(01)00002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liebman PA, Entine G. Science. 1974;185:457–459. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4149.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scheuring S, Ringler P, Borgnia M, Stahlberg H, Muller DJ, Agre P, Engel A. EMBO J. 1999;18:4981–4987. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.18.4981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walz T, Tittmann P, Fuchs KH, Muller DJ, Smith BL, Agre P, Gross H, Engel A. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;264:907–918. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dean MK, Higgs C, Smith RE, Bywater RP, Snell CR, Scott PD, Upton GJ, Howe TJ, Reynolds CA. J. Med. Chem. 2001;44:4595–4614. doi: 10.1021/jm010290+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nair KS, Balasubramanian N, Slepak VZ. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:421–425. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00691-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seno K, Kishimoto M, Abe M, Higuchi Y, Mieda M, Owada Y, Yoshiyama W, Liu H, Hayashi F. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:20813–20816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100032200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schertler GF, Hargrave PA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995;92:11578–11582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guo W, Shi L, Javitch JA. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:4385–4388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200679200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Filipek S, Stenkamp RE, Teller DC, Palczewski K. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003;65:851–879. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okada T, Palczewski K. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001;11:420–426. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00227-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marshall GR. Biopolymers. 2001;60:246–277. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2001)60:3<246::AID-BIP10044>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wessling-Resnick M, Johnson GL. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:3697–3705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arimoto R, Kisselev OG, Makara GM, Marshall GR. Biophys J. 2001;81:3285–3293. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75962-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Min KC, Gravina SA, Sakmar TP. Protein Expression Purif. 2000;20:514–526. doi: 10.1006/prep.2000.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Granzin J, Wilden U, Choe HW, Labahn J, Krafft B, Buldt G. Nature. 1998;391:918–921. doi: 10.1038/36147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schubert C, Hirsch JA, Gurevich VV, Engelman DM, Sigler PB, Fleming KG. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:21186–21190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.30.21186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henderson R, Schertler GF. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1990;326:379–389. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1990.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dratz EA, Van Breemen JF, Kamps KM, Keegstra W, Van Bruggen EF. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1985;832:337–342. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(85)90268-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Corless JM, McCaslin DR, Scott BL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1982;79:1116–1120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.4.1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liebman PA, Weiner HL, Drzymala RE. Methods Enzymol. 1982;81:660–668. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(82)81091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cone RA. Nat. New Biol. 1972;236:39–43. doi: 10.1038/newbio236039a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liebman PA, Parker KR, Dratz EA. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1987;49:765–791. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.49.030187.004001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blasie JK, Worthington CR. J. Mol. Biol. 1969;39:417–439. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blasie JK, Dewey MM, Blaurock AE, Worthington CR. J. Mol. Biol. 1965;14:143–152. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saibil H, Chabre M, Worcester D. Nature. 1976;262:266–270. doi: 10.1038/262266a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yeager MJ. Brookhaven Symp. Biol. 1976:III3–III36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bruckert F, Chabre M, Vuong TM. Biophys. J. 1992;63:616–629. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81650-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hamm HE, Bownds MD. Biochemistry. 1986;25:4512–4523. doi: 10.1021/bi00364a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matthews RG, Hubbard R, Brown KP, Wold G. J. Gen. Physiol. 1963;47:215–240. doi: 10.1085/jgp.47.2.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wagner HJ, Frohlich E, Negishi K, Collin SP. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 1998;17:637–685. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(98)00003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Okada T, Ernst OP, Palczewski K, Hofmann KP. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2001;26:318–324. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01799-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van Hooser JP, Aleman TS, He YG, Cideciyan AV, Kuksa V, Pittler SJ, Stone EM, Jacobson SG, Palczewski K. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:8623–8628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.150236297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]