Abstract

Lipopolysaccharides (LPS), otherwise termed ‘endotoxins’, are an integral part of the outer leaflet of the outer-membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. Lipopolysaccharides play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of ‘Septic Shock’, a major cause of mortality in the critically ill patient, worldwide. The sequestration of circulatory endotoxin may be a viable therapeutic strategy for the prophylaxis and treatment of Gram-negative sepsis. We have earlier shown that the pharmacophore necessary for small molecules to bind LPS is simple, comprising of two protonatable cationic functions separated by about 15Å, permitting the simultaneous interaction with the negatively charged phosphates on lipid A, the toxically active center of endotoxin. In this report, we employ high-throughput screening methods, using a novel fluorescent probe displacement method. Searches in three-dimensional structure databases yielded about ~ 4000 commercially available small molecules, each possessing two cationic functions spaced approximately 15Å apart. Approximately 400 such compounds have been screened in an effort to validate the method by which high-affinity endotoxin binders can be identified. We show that the IC50 values that are obtained from the fluorescence-based primary screen are correlated both to the enthalpy of binding, as measured by isothermal titration calorimetry, as well as to biological potency in vitro assays. By performing rapid toxicity screens in tandem with the bioassays, lead compounds of interest can be easily identified for further systematic structural modifications and SAR studies.

Keywords: Endotoxin, Lipopolysaccharide, Sepsis, shock, Fluorescence, High-throughput screening

Abbreviations: BC: BODIPY TR cadaverine; (5-(((4-(4,4-difluoro-5-(2-thienyl)-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene-3-yl) phenoxy)acetyl)amino)pentylamine, hydrochloride, BC); DC: Monodansylcadaverine; HTS: High-throughput screening; ITC: Isothermal titration calorimetry; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; NED: N-1-napthylenediamine; PBS: Phosphate-buffered saline; PMB: Polymyxin B; PMS: Phenazine methosulfate; XTT: 2,3-Bis(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide 2,3-Bis(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide inner salt

Introduction

The incidence and mortality due to Gram-negative sepsis continues to rise unabated worldwide, despite new advances in antimicrobial chemotherapy [1–4], emphasizing a clear, unmet need to develop therapeutic options specifically targeting the pathophysiology of sepsis. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), or ‘endotoxin’, the principal constituent of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria [5–7], play a key role in the pathogenesis of Gram-negative sepsis via the activation of systemic inflammatory cascades [8–11]. The toxically active moiety of LPS is a negatively charged, amphipathic glycolipid termed Lipid A [12], which is composed of a hydrophilic, bis-phosphorylated (bis-anionic) diglucosamine backbone, and a hydrophobic domain of six (E. coli) or seven (Salmonella) acyl chains in amide and ester linkages [13–15]. For the reasons that lipid A is the toxic moiety of LPS specifically recognized by receptors on LPS-responsive cells [16–23], and is highly structurally conserved amongst all Gram-negative bacteria [24], it represents a logical molecular target for purposes of developing therapeutic strategies for the therapy and prophylaxis of Gram-negative sepsis.

The anionic and amphiphilic nature of lipid A enables it to bind to numerous substances which are positively charged and also possess amphipathic character, including proteins [25, 26], peptides [27–31], pharmaceutical compounds [32, 33], and other synthetic polycationic amphiphiles [34–37]. Importantly, from these and currently ongoing studies, we have determined the pharmacophore necessary for optimal recognition and neutralization of lipid A [33] by small molecules, exemplified by the lipopolyamines (for a recent review, see Ref. [38]). Our identification of the lipopolyamines as potential endotoxin sequestering molecules was based on two simple heuristics which have been experimentally tested and validated: (1) An optimal distance of ~14 Å is necessary between protonatable functions in bis-cationic molecules for simultaneous ionic interactions with the glycosidic phosphates on lipid A; it is the bis-cationic scaffold that is the principal determinant of binding affinity. (2) Binding is necessary, but not sufficient for activity, and an additional, appropriately positioned hydrophobic group is obligatory for the interaction to manifest in neutralization of endotoxicity. We now ask the questions: What are the structural features of the bis-cationic scaffold that govern binding affinity? Can one choose or design scaffolds of small molecules such that they possess those features that enhance binding affinity?

While definitive answers will have to await the careful analyses of experimental data, much information can be gleaned from already available structural data on oligosaccharide-protein interactions, given that the geometry of binding of small molecules to LPS is such that the scaffold overlies the bis-d-glucosamine backbone of lipid A [38]. About a hundred high-resolution crystal structures on protein-carbohydrate complexes exist [39] in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [40]. Of these, 20 complexes contain disaccharides, 14 contain a trisaccharide, and 24 contain tetrasaccharides or longer oligosaccharides. Particularly instructive are complexes between innate immune response proteins from the horse-shoe crab, and their cognate carbohydrate ligands. These phylogenetically ancient invertebrates altogether lack an adaptive immune system, and rely solely on innate mechanisms for host defense. Currently, the only FDA-approved in vitro method for testing parenteral solutions for endotoxin contaminantion uses the lysate from hemocytes of Limulus polyphemus or Tachypleus tridentatus (the American and Japanese horse-shoe crab, respectively) [41]. A 1.5Å crystal structure of a Limulus-derived endotoxin-binding protein [42] currently undergoing Phase-I clinical trials [43–46], reveals a well-demarcated hydrophobic patch and two clusters of cationic Lys/Arg residues, but is unliganded. The tachylectins are a family of lectins found in Tachypleus hemocyte granules that behave like carbohydrate pattern-recognition receptors, binding to core sugar sequences in LPS, lipoteichoic acid, and fungal (1,3)-β-d-glucan, and activating downstream coagulation cascades. The crystal structures of Tachylectin-2 (1TL2) and Tachylectin-5A (1JC9) bound to carbohydrate ligands have recently become available. A common theme that emerges upon a close examination of these structures as well as lectin-oligosaccharide complexes (e.g., 1SLC, 2KMB, 1HGG, 1TEI, 1JPC, 1VPS) is that the complexes are stabilized primarily via a combination of polar H-bonds with the sugar hydroxyls and weak van der Waals forces.

We hypothesize, therefore, that a judicious pre-selection of bis-cationic compounds fulfilling the primary pharmacophore criterion of an inter-nitrogen distance of ~14 Å, and bearing multiple H-bond donor/acceptor atoms on the scaffold would increase the probability of generating high-affinity binders (“hits”). Searches in three-dimensional structure databases yielded about ~ 4000 commercially available compounds, each possessing two protonatable cationic functions [42] spaced approximately 15Å apart. In this report, we employ high-throughput screening methods, using a novel fluorescent probe displacement method described in the accompanying paper. Approximately 400 such compounds have been screened in an effort to validate the method by which high-affinity endotoxin binders can be identified. We show that the IC50 values that were obtained from the fluorescence-based primary screen are correlated both to the enthalpy of binding, as measured by isothermal titration calorimetry, as well as to biological potency in vitro assays. By performing rapid toxicity screens in tandem with the bioassays, lead compounds of interest can be easily identified for further systematic structural modifications and SAR studies, by appending suitably positioned long-chain acyl or alkyl substituents to convert high-affinity binders to high-potency LPS sequestrants.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

BODIPY TR cadaverine (5-(((4-(4,4-difluoro-5-(2-thienyl)-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene-3-yl) phenoxy)acetyl)amino)pentylamine, hydrochloride, BC) was purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA). LPS from E. coli serotype 0111:B4 was from List Biological Labs, Inc., CA, USA. RPMI-1640 cell-culture medium, polymyxin B Sulfate, NED (N-1-napthylenediamine), sulfanilamide, fetal bovine serum, and XTT (2,3-Bis(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide) sodium salt were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). J774.A1 cells (a gift from Dr. P. Silverstein, Univ. of Kansas) were originally obtained from the American Type Tissue Collection (Manassas, VA). In implementing the fluorescence assay in high throughput format, we compared 384 well, flat bottom, black polystyrene/polypropylene plates from a variety of vendors. 96-well microtiter plates used for the bioassays were from Corning Costar.

Construction of Focused Virtual Library

We have implemented the following strategies in generating our focused library: (a) Maximize chemical diversity; (b) Select for fulfilment of Lipinski’s criteria [47]; (c) Eliminate molecules with chemically reactive functionalities prone to generate false-positives [48]; (d) Choose bis-cationic molecules with an N↔N distance of ~14 Å with a bias for structures with multiple H-bond donor/atoms on the scaffold. A 2D chemical database comprising of a collated superset of commercially available chemical structures was obtained from ChemNavigator, Inc. (San Diego, CA). The October 2003 release of the ChemNavigator database comprises of 16.3 million total chemical entities from 110 international vendors, of which 9.3 million are unique compounds. First, all molecules possessing reactive functionalities such as epoxides, aziridines, perhalo ketones, alkyl/acyl halides, anhydrides, halopyrimidines etc., that might yield false-positives [48] were eliminated. Next, those molecules falling outside +2 standard deviations (of the sample) from Lipinski requirements [47]were deleted. 3D coordinates were generated for this master-set using the Concord [49] module in Tripos (Tripos, Inc., St. Louis, MO) on a Silicon Graphics Octane machine. A 3D-substructure search was performed in order to select for bis-cationic molecules. A search criterion of NH2↔NH2 distance of 15 Å with a tolerance of 3 Å was applied. This search algorithm also identifies bis-amidinium and -guanidium compounds, which we have shown also to bind LPS. Approximately 6,000 compounds were identified which were then parsed to enrich for scaffolds with suitable H-bond donor/acceptor groups. The compounds comprising the final focused library were optimized for chemical diversity employing the Tanimoto metric [50] as implemented in the DiverseSolutions module of the Tripos software, and have the following properties: n=2485, molecular weight: 391±96 [mean±sd], cLogP: 3.196±1.703, and cLogD:2.016±1.395 with median H-bond donor and acceptor numbers of 4 and 7.

Compound Acquisition

We have started acquiring compounds incrementally from various vendors. As of yet, we have examined ~ 400 compounds obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), Asinex (Moscow, Russia), Nanosyn (Menlo Park, CA), and the National Cancer Institute Open Compound Collection (Bethesda, MD). The Asinex, Nanosyn, and NCI compounds are referred to in this paper with BAS, NS and NCI prefixes, respectively, while the Sigma-Aldrich compounds have numeric-only identifiers. 5 mM stock solutions were prepared in either 50 mM Tris buffer, or buffer containing 50% DMSO. The presence of DMSO was verified not to interfere with the BC:LPS displacement assay.

Pilot High-throughput Primary Screen

The Bodipy-cadaverine (BC) displacement assay to quantify the affinities of binding of compounds to LPS has been described in detail in the preceding paper. This assay was adapted to the HTS format as follows. The first column (16 wells) of a 384-well plate contained 15 test compounds plus polymyxin B, all at 5 mM, and were serially two-fold diluted across the remaining 23 columns, achieving a final dilution of 0.596 nM in a volume of 40 μl. PMB served as the positive control and reference compound for every plate, enabling the quantitative assessment of repeatability and reproducibility (CV and Z’ factors) for the assay. Robotic liquid handling was performed on a Precision 2000 automated microplate pipetting system, programmed using the Precision Power software, Bio-Tek Instruments Inc., VT, USA. Stock solutions of LPS (5 mg/ml) and BC (500 μM) were prepared in Tris buffer (pH 7.4, 50 mM). 1 ml each of the LPS and BC stocks were mixed and diluted in Tris buffer to a final volume of 100 ml, yielding final concentrations of 50 μg/ml of LPS and 5 μM BC. 40 μl of this BC:LPS mixture was added to each well of the plate using the Precision 2000. Fluorescence measurements were made at 25 °C on a Fluoromax-3 with Micromax Microwell 384-well plate reader, using DataMax software, Jobin Yvon Inc., NJ. The BC excitation wavelength was 580 nm, emission spectra were taken at 620 nm with both emission and excitation monochromator bandpasses set at 5 nm. We compared the performance of 384-well, flat bottom, black polystyrene/polypropylene plates from a variety of vendors. Effective displacements (ED50) were computed at the midpoint of the fluorescence signal versus compound concentration displacement curve, determined using an automated four-parameter sigmoidal fit utility of the Origin plotting software (Origin Lab Corp., MA), as described in the preceding paper. Z’ factors [51] were computed using the equation: 1-[3(SD+SD’)/(A-A’)] where SD and SD’, A and A’ are standard deviations for the signal and noise, and means of signal and noise, respectively. The fluorescence of BC is quenched upon binding to LPS, and the displacement of BC by PMB, the prototype LPS sequestrant, results in de-quenching (intensity enhancement) of BC fluorescence. Since PMB was included as a positive control/reference compound in every plate, it was convenient to index Z’ factor calculations to PMB displacements. The maximum fluorescence intensity (PMB at high concentration) was taken to be the signal and the minimum BC emission (PMB at high dilution) was taken to be the noise. Z’ factors were computed from 15 independent PMB displacement curves obtained from separate experiments.

Nitric Oxide Assay

Nitric oxide production was measured as total nitrite in murine macrophage J774.A1 cells using the Griess reagent system [52, 53]. J774.A1 cells were grown in RPMI-1640 cell-culture medium containing l-glutamine and sodium bicarbonate and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% l-glutamine-penicillin-streptomycin solution, and 200 μg/ml l-arginine at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were plated at ~105/ml in a volume of 100 μl/well, in 96 well, flat-bottomed, cell culture treated microtiter plates until confluency and subsequently stimulated with 10 ng/ml lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Concurrent to LPS stimulation, serially diluted concentrations of test compounds were added to the cell medium and left to incubate overnight for 16h. Polymyxin B was used as reference compound in each plate. Positive- (LPS stimulation only) and negative-controls (J774.A1 medium only) were included in each experiment. Nitrite concentrations were measured adding 50 μl of supernatant to equal volumes of Griess reagents (50 μl/well; 0.1% NED solution in ddH2O and 1% sulfanilamide, 5% phosphoric acid solution in ddH2O) and incubating for 15 minutes at room temperature in the dark. Absorbance at 535 nm was measured using a Molecular Devices Spectramax M2 multifunction plate reader (Sunnyvale, CA). Nitrite concentrations were interpolated from standard curves obtained from serially diluted sodium nitrite standards.

In vitro XTT cytotoxicity Assay

The determination of cell viability was accomplished by the addition of an XTT solution to J774.A1 cultures [54, 55] treated with graded concentrations of the test compounds. Cell culture and plating procedures were performed as described previously for nitric oxide measurement. J774.A1 cells in 96 well plates were treated with serially diluted concentrations of PMB, or test compounds to a final volume of 200 μl/well and left to incubate at 37°C for 16h. Wells containing J774.A1 medium only served as the negative control. Cytotoxicity was measured the following day by the addition of 80 μl/well XTT/Phenazine methosulfate (PMS) solution (XTT solution, 2 mM in PBS, pH 7.4, pH adjusted to 6.0-6.5; PMS solution, 0.92 mg/ml in PBS, pH 7.4; solutions mixed at a ratio of 8 ml XTT solution to 200 μl PMS solution) followed by an incubation time of 1.5h at 37°C. Absorbance was read at 490 nm with scatter correction at 690 nm..

Isothermal Calorimetry (ITC)

All ITC experiments were performed using a VP-ITC Microcalorimeter (Microcal Inc., MA, USA). A typical titration experiment involved 35 consecutive injections at 360 s intervals consisting of 3 μl injections of LPS into the sample cell (cell volume: 1.4119 ml) containing the ligand, at 37 °C in Tris buffer (pH 7.4, 50 mM). The titration cell was stirred continuously at 310 rpm. Care was taken to ensure that both LPS and ligand were dissolved in the same buffer, and appropriate control experiments (LPS injected into buffer, BC injected into buffer) were performed. The resulting data were then analyzed using Microcal’s ITC data analysis package, VP Viewer 2000, which uses the scientific plotting software, Origin 7 (Origin Lab. Corp., MA, USA).

Results and Discussion

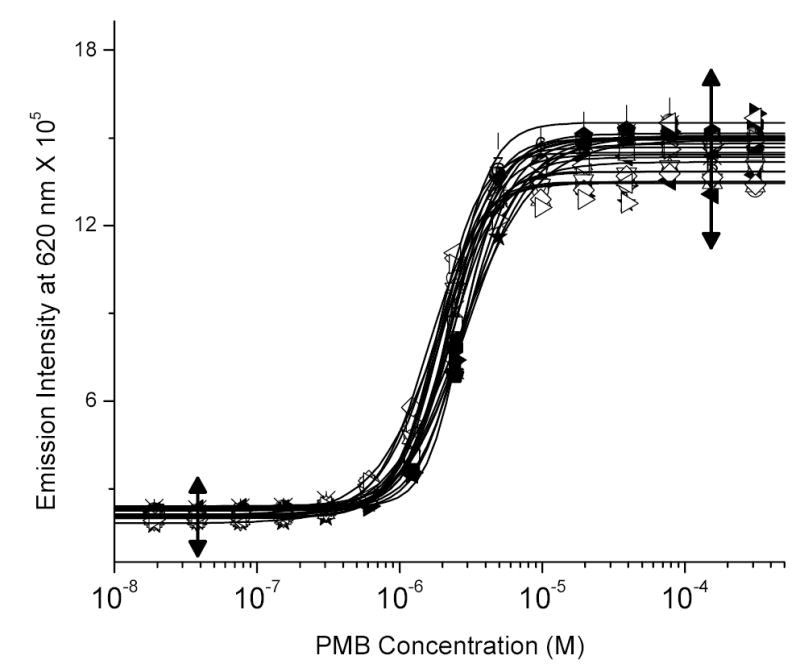

The fluorescence displacement assay described in the preceding paper was easily and robustly adapted to a high-throughput format, yielding excellent S/N ratios. The assay, in its entirety, consists of three steps: (i) in-plate serial dilution of compounds; (ii) addition of a mixture of LPS and BC; and (iii) recording end-point fluorescence intensity at a fixed wavelength plate in a fluorometer. With polymyxin B used as the reference compound, we obtained inter-plate CVs of 5.2% and a Z’ factor of 0.821 (Fig (1)). The choice of the 384-well black polystyrene plates used for the HTS assay was crucial. Most commercially available plates have untreated surfaces and are designated “high bind”. These plates rapidly adsorb the LPS:BC mixtures, leading to a time-dependent loss of fluorescence signal, with a 50% signal loss occurring within an hour, and were therefore not optimal. In evaluating about eight brands of plates, we found that Corning Nonbinding Surface microplates (Fisher Catalog 07-201-104), which have a nonionic polyethyleneoxide-type polymer coating obviated adsorption-induced losses of the fluorophore. Fluorescent readouts obtained from these plates were stable essentially indefinitely, and were used for all the experiments reported in this paper.

Fig. (1).

Displacement of LPS-bound BC by polymyxin B obtained from 17 independent experiments. The data points were fit by an automated four-parameter logistic fitting function as implemented in Origin 7.0. The left and right arrows indicate, respectively, the “negative” and “positive” data points for computing Z’ factor (0.82117). The CVs for the negative and positive data points were, respectively, 4.115% and 6.26%.

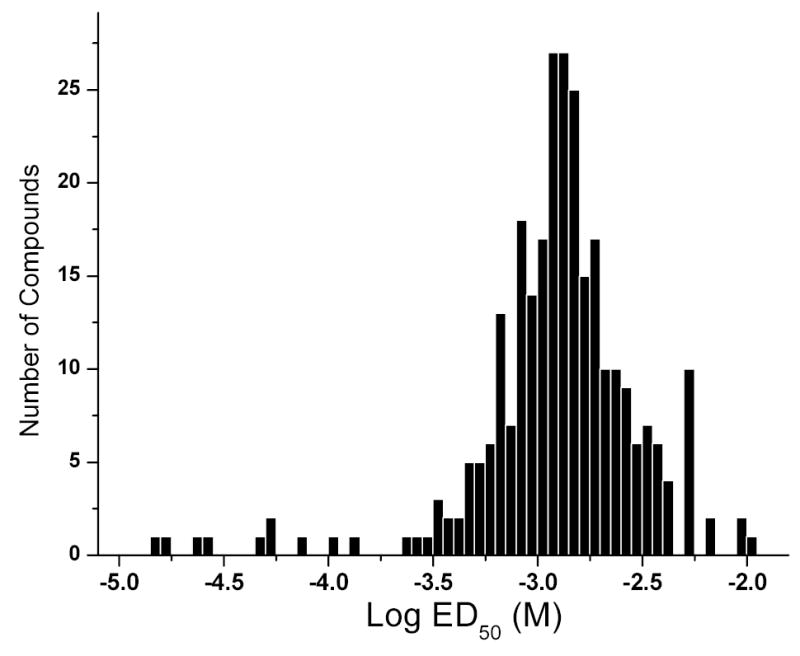

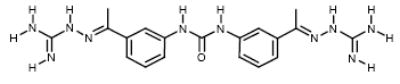

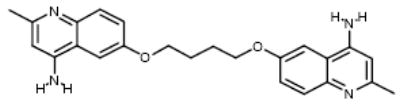

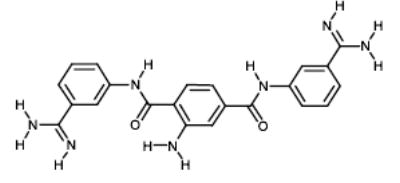

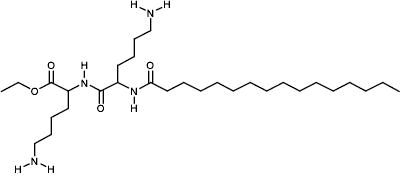

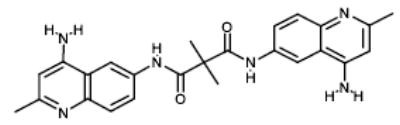

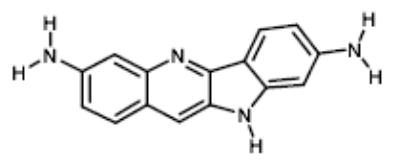

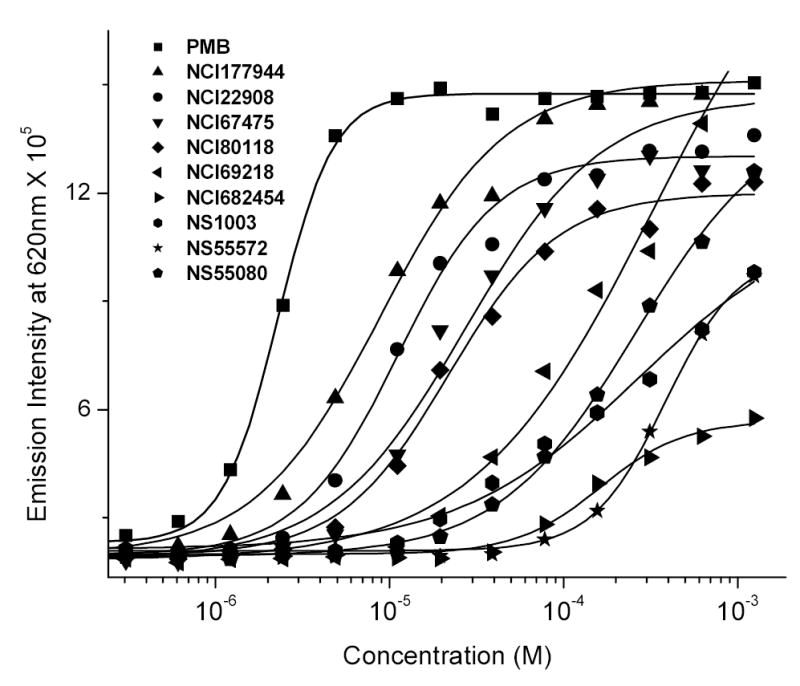

Fig. (2) depicts the distribution of ED50 values for the ~400 compounds obtained from the pilot HTS screen. Most compounds are of millimolar affinity. This was as expected since these compounds lack a terminal long-chain alkyl chain which greatly enhances binding affinity via additional hydrophobic interactions with the polyacyl domain of lipid A [32, 33, 38], as exemplified, for instance, by the relative affinities of polymyxin B and its nonapeptide derivative (see preceding paper). The structures of the “top ten” higher affinity compounds with ED50 values ranging from 15 μM to 135 μM are depicted in Table (1) and the raw data of the BC displacement profiles of representative compounds with a broad range of relative affinities are shown in Fig. (3). As is evident from Fig. (3), the BC displacement assay has a large dynamic range, enabling the facile determination of reliable ED50 values from nanomolar to millimolar range. The simplicity and robustness of this high-throughput method renders it an ideal primary screen for the rapid identification of high-affinity LPS binders.

Fig. (2).

Distribution of ED50 values (relative affinities) of ~400 compounds as determined by the BC:LPS displacement assay in the high-throughput format. The structures of the top-ten ranked compounds are shown in Table (1).

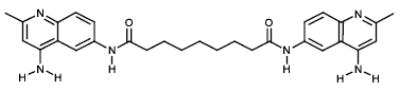

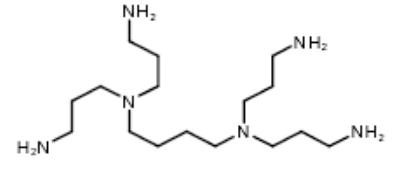

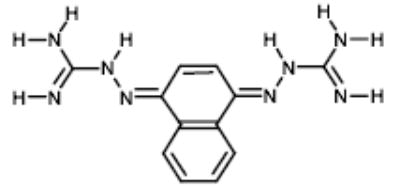

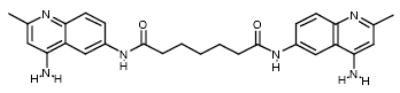

Table 1.

| No. | STRUCTURE | Compound ID | ED50 (μM) | IC50 (mM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

PMB | 2.29 | 0.98 |

| 2 |

|

NCI177944 | 14.91 | 11.79 |

| 3 |

|

NCI22905 | 17.29 | 36.5 |

| 4 |

|

NCI22908 | 22.87 | 39.19 |

| 5 |

|

4,6069-9 | 27.89 | 6.57 |

| 6 |

|

NCI67475 | 47.74 | 31.95 |

| 7 |

|

NCI22904 | 50.67 | 75.69 |

| 8 |

|

NCI80118 | 51.68 | 25.59 |

| 9 |

|

NCI282192 | 74.53 | 7.19 |

| 10 |

|

NCI12156 | 101.5 | 83.33 |

| 11 |

|

NCI682454 | 135.08 | ND |

Fig. (3).

Displacement of LPS-bound BC by polymyxin B (reference compound) and representative test compounds. The ED50 values (in μM) are as follows. PMB: 2.2; NCI177944: 14.91; NCI22908: 22.97; NCI67475: 47.74; NCI80118: 51.68; NCI69218: 76.23; NCI682454: 135.08; Nanosyn1003: 311.03; Nanosyn55572: 325.59; Nanosyn55080: 449.81.

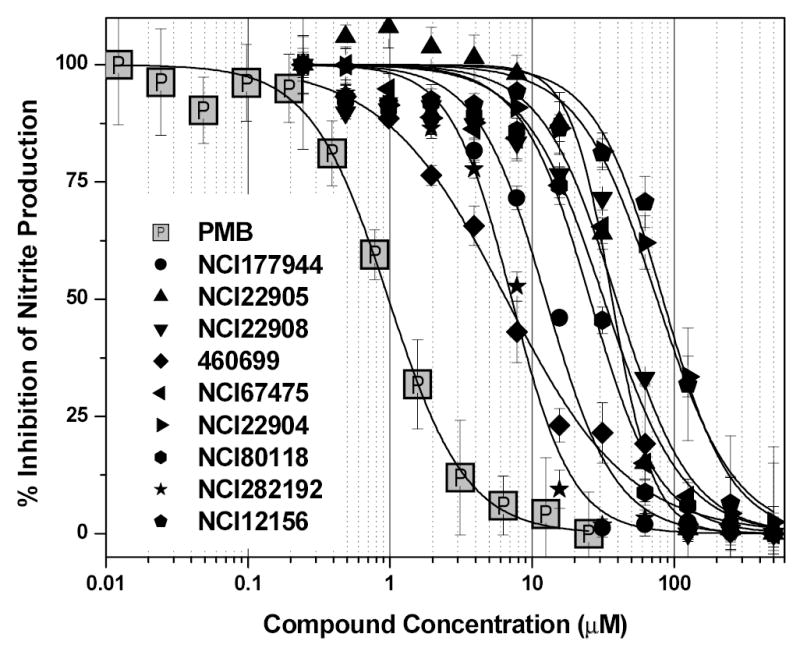

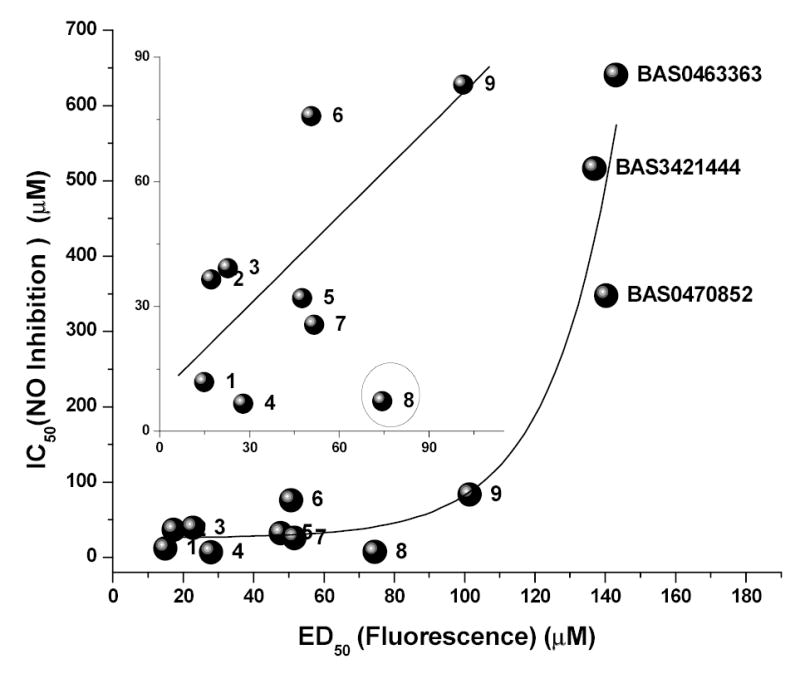

Having identified high-affinity LPS binders in the pilot HTS screen, it was important to verify that the binding affinity corresponded to biological potency. From our earlier work [31, 35–37, 56, 57], we have shown that the inhibition of nitric oxide (NO) production (measured as nitrite in a HTS-scalable, homogeneous, colorimetric assay) in LPS-stimulated murine J774 cells is a cost-effective primary biological screen that rivals far costlier and non-HTS scalable cytokine immunoassays in accuracy and predictive value. We have therefore used the NO assay as our first-tier biological screen, the results of which are shown in Fig. (4), and Table (1). To a first approximation, there is an exponential relationship between the ED50 (determined by the HTS fluorescence assay) and the IC50 (NO inhibition assay) values (Fig. (5)). However, a closer inspection of a subset of the high-affinity compounds reveals a linear relationship (r = 0.825) with Compound #8 (4,6069-9) being a prominent outlier (Fig. (5 inset)). The biological potency of this compound is considerably higher than that would be predicted from its affinity. Of the approximately 400 compounds examined in this study, only the 4,6069-9 bears a long-chain aliphatic acyl group, which we have earlier shown to be a key structural determinant in ascribing LPS-neutralizing activity [32, 36–38, 56]. This polyamidoamine-type monondendron acylated compound [58] has indeed been found previously to be a lead in biological assays [38]. This finding is most encouraging since it not only independently confirms the validity of a lead obtained previously, but also suggests that high-potency LPS sequestrants can be generated if a promising scaffold (NCI177944, for instance) were to be appropriately modified so as to incorporate sterically optimal long-chain aliphatic hydrocarbon substituents. This is presently being tested.

Fig. (4).

Nitric oxide inhibition by the top-ranked compounds shown in Table 1. Murine J774.A1 cells were stimulated for 14 h with 10 ng/ml E. coli 0111:B4 LPS, mixed with graded concentrations of compounds. Nitric oxide was measured as total nitrite using the Griess assay. % Inhibition (Y-axis) was computed from positive (Rmax; LPS only) and negative (R0; cell-culture medium only) controls using the formula (Rmax-R0)/(Rmax-Rcompound). Inhibition constant (IC50) values, determined from the four-parameter logistic fits, are presented in Table 1. The IC50 for Polymyxin B is 0.977 μM.

Fig. (5).

The relationship between ED50, determined by the primary HTS fluorescence assay and IC50 values, measured by inhibition of NO production in J774 cells. Numerals represent the ranking by ED50 as given in Table (1). To a first approximation, a exponential growth curve can be fit to the data points. Inset: Plot of the top-nine high-affinity compounds showing a linear relationship. Compound 8 (encircled) is an outlier.

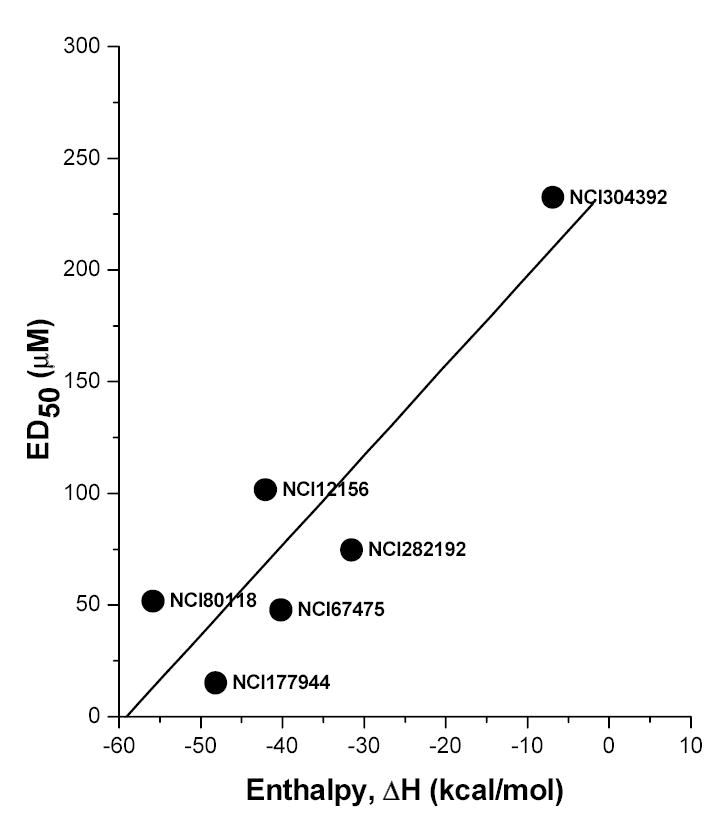

Starting from a hit, the rational design and development of second-generation lead compounds involves the optimization of the binding affinity. This is most directly addressed using thermodynamic principles, given that the association constant, Ka, equals e-ΔG/RT, where ΔG, the Gibbs energy is the sum of ΔH, the enthalpy and –TΔS, where ΔS is the entropic term. It follows that a gain in binding affinity may be accomplished by either increasing the enthalpic term, or by decreasing the entropic offsets. An excellent example whereby this strategy has been employed systematically and successfully is in the design of novel HIV-1 protease inhibitors [59]. It is of interest that the driving force of interaction of most HIV protease inhibitors in current clinical use is a large positive entropic change originating from the burial of hydrophobic surface upon binding to the protease [60]. Preparatory to structure-based ligand design that would follow future large-scale screening campaigns, we were interested first in examining whether a relationship could be established between the observed ED50 values derived from the HTS screening and the thermodynamic parameters from isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments, and whether the binding of the compounds to LPS were enthalpically or entropically driven. The ITC thermograms of all the compounds tested were exothermic and saturable (data not shown). As shown in Fig. (6), the ED50 values of a subset of the compounds are highly correlated (r = 0.892) with enthalpy, but not with the entropy (r = —0.126) of binding (data not shown). This is consistent not only with our previous observations over the years that the binding is driven primarily by electrostatic forces, but further suggests that affinity may be augmented by additional H-bond interactions between the backbone of the compound, and that of lipid A [38]. These observations would also suggest that once a strongly enthalpically-driven high-affinity lead is found, further improvements in binding affinity may be achieved by minimizing entropic losses by limiting the conformational flexibility of the scaffold.

Fig. (6).

Relationship of enthalpy of binding to ED50 values of a subset of test compounds. ΔH (and ΔS) were determined by ITC and ED50 values were derived from HTS screening. The binding of the compounds is primarily enthalpy driven (r = 0.892). There was no correlation (r = −0.126) between ΔS and ED50 (not shown).

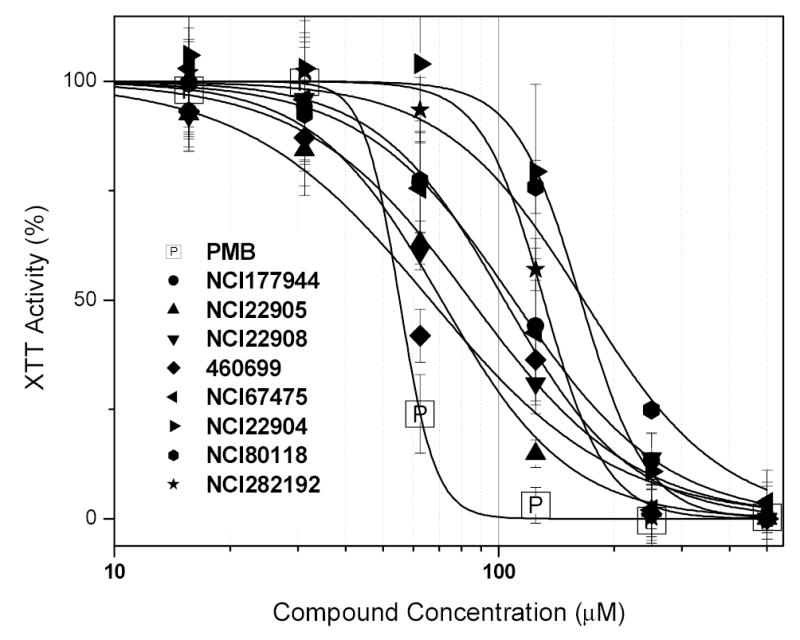

It is to be emphasized that no matter how efficacious a compound, it is unlikely to be ultimately of clinical value unless it has an acceptable safety profile, and it is important to take into account toxicity issues alongside efficacy in the rational design and development of LPS-sequestering drug candidates. A survey of TOXLINE and other toxicological databases indicate that, for the vast majority of cationic amphiphilic compounds such as the ones we are interested in screening, the chief toxicity in vertebrate animals appears to be nonspecific cytotoxicity, a consequence of membranophilic and membrane-destabilizing properties. We have therefore screened the top-ten compounds in an in vitro cytotoxicity panel using a variety of cell lines, and different assays, each probing specific organelle functions. Shown in Fig. (7) are the results of a representative cytotoxicity (XTT) assay in J774 cells, which reports on mitochondrial function [54, 55]. Polymyxin B, as expected, is the most toxic with an IC50 value of 55 μM, while that of most of the test compounds are between 100 and 200 μM. While these are not yet ‘ideal’ leads with which to pursue extensive SAR studies, we feel it important to winnow out problematic scaffolds early on in the process of identifying novel anti-endotoxin candidates.

Fig. (7).

In vitro toxicity screen of high-affinity compounds using the XTT assay in murine J774 cells.

In conclusion, we present a novel and robust high-throughput screening method for the rapid identification of endotoxin-neutralizing agents amongst a focused library comprising of preselected candidates, each of which possess the pharmacophore for LPS recognition. The readouts of the primary fluorescence-based HTS screen are correlated with both the biological potency and the enthalpy of interaction. By performing in vitro toxicity screens in tandem with the bioassays, lead compounds of interest can be easily identified for further systematic structural modifications and SAR studies. Detailed SAR studies will be reported elsewhere upon screening the entire focused library.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported from NIH grants 1R01 AI50107, 1U01 AI54785, and 1U01 AI056476, and a First Award Grant from P20 RR015563 from the COBRE Program of the National Center for Research Resources and matching support from the State of Kansas, and the University of Kansas or Kansas State University.

References

- 1.Gelfand JA, Shapiro L. New Horizons. 1993;1:13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gasche,Y., Pittet,D., and Sutter,P. (1995). Outcome and prognostic factors in bacteremic sepsis. In Clinical trials for treatment of sepsis, W.J.Sibbald and J.L.Vincent, eds. (Berlin: Springer-Verlag), pp. 35–51.

- 3.MMWR,1990, 39, 31.

- 4.Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, Moss M. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1546. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lüderitz O, Galanos C, Rietschel ET. Pharmacol Ther. 1982;15:383. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(81)90051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rietschel ET, Kirikae T, Schade FU, Mamat U, Schmidt G, Loppnow H, Ulmer AJ, Zähringer U, Seydel U, Di Padova F, et al. FASEB J. 1994;8:217. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.2.8119492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rietschel,E.T., Brade,L., Lindner,B., and Zähringer,U. (1992). Biochemistry of lipopolysaccharides. In Bacterial endotoxic lipopolysaccharides, vol.I. Molecular biochemistry and cellular biology, D.C.Morrison and J.L.Ryan, eds. (Boca Raton: CRC Press), pp. 1–41.

- 8.Hoffman WD, Natanson C. Anesth Analg. 1993;77:613. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199309000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bone RC, Sprung CL, Sibbald WJ. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:724. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, Schein RM, Sibbald WJ. Chest. 1992;101:1644. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bone RC. Clin Chest Med. 1996;17:175. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(05)70307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galanos C, Lüderitz O, Rietschel ET, Westphal O, Brade H, Brade L, Freudenberg MA, Schade UF, Imoto M, Yoshimura S, Kusumoto S, Shiba T. Eur J Biochem. 1985;148:1. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb08798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferguson AD, Hofmann E, Coulton J, Diedrichs K, Welte W. Science. 1998:2215. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirikae T, Schade FU, Zähringer U, Kirikae F, Brade H, Kusumoto S, Kusama T, Rietschel ET. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1994;8:13. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1994.tb00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kusumoto,S., Inage,M., Chaki,H., Imoto,M., Shimamoto,T., and Shiba,T. (1983). Chemical synthesis of lipid A for the elucidation of structure-activity relationships. In Bacterial lipopolysaccharides: structure, synthesis, and biological activities, L.Anderson and F.M.Unger, eds. American Chemical Society), pp. 237–254.

- 16.Beutler B, Poltorak A. Drug Metab Dispos. 2001;29:474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ingalls RR, Heine H, Lien E, Yoshimura A, Golenbock D. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1999;13:341. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70078-7. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lien E, Means TK, Heine H, Yoshimura A, Kusumoto S, Fukase K, Fenton MJ, Oikawa M, Qureshi N, Monks B, Finberg RW, Ingalls RR, Golenbock DT. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:497. doi: 10.1172/JCI8541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu MY, Huffel CV, Du X, Birdwell D, Alejos E, Silva M, Galanos C, Freudenberg M, Ricciardi CP, Layton B, Beutler B. Science. 1998;282:2085. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ulevitch RJ, Tobias PS. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:437. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.002253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ulevitch RJ. Adv Immunol. 1993;53:267. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60502-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall JC. Nature Rev Drug Disc. 2003;2:391. doi: 10.1038/nrd1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeni F, Freeman B, Natanson C. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:1097. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199707000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holst,O., Ulmer,A.J., Brade,H., and Rietschel,E.T. (1994). On the chemistry and biology of bacterial endotoxic lipopolysaccharides. In Immunotherapy of infections, N.Masihi, ed. (New York, Basel, Hong Kong: Marcel Dekker, Inc.), pp. 281–308.

- 25.David SA, Balaram P, Mathan VI. J Endotoxin Res. 1995;2:99. [Google Scholar]

- 26.David,S.A. (1999). The interaction of lipid A and lipopolysaccharide with human serum albumin. In Endotoxins in health and disease, H.Brade, S.M.Opal, S.N.Vogel, and D.C.Morrison, eds. (New York: Marcel Dekker), pp. 413–422.

- 27.Bhattacharjya S, David SA, Mathan VI, Balaram P. Biopolymers. 1997;41:251. [Google Scholar]

- 28.David SA, Bhattacharjya S, Mathan VI, Balaram P. J Endotoxin Res. 1994;1(suppl):A60. [Google Scholar]

- 29.David SA, Balaram P, Mathan VI. Med Microbiol Lett. 1993;2:42. [Google Scholar]

- 30.David SA, Mathan VI, Balaram P. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1123:269. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(92)90006-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.David SA, Awasthi SK, Balaram P. J Endotoxin Res. 2000;6:249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.David SA, Bechtel B, Annaiah C, Mathan VI, Balaram P. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1212:167. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(94)90250-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.David SA, Mathan VI, Balaram P. J Endotoxin Res. 1995;2:325. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vaara M. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1983;18:117. [Google Scholar]

- 35.David SA, Awasthi SK, Wiese A, Ulmer AJ, Lindner B, Brandenburg K, Seydel U, Rietschel ET, Sonesson A, Balaram P. J Endotoxin Res. 1996;3:369. [Google Scholar]

- 36.David SA, Perez L, Infante MR. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2002;12:357. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00749-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.David SA, Silverstein R, Amura CR, Kielian T, Morrison DC. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:912. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.4.912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.David SA. J Molec Recognition. 2001;14:370. doi: 10.1002/jmr.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bush CA, Martin-Pastor M, Imberty A. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1999;28:269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.28.1.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berman HM, Battistuz T, Bhat TN, Bluhm WF, Bourne PE, Burkhardt K, Feng Z, Gilliland GL, Iype L, Jain S, Fagan P, Marvin J, Padilla D, Ravichandran V, Schneider B, Thanki N, Weissig H, Westbrook JD, Zardecki C. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58:899. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902003451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roth RI, Tobias PS. Infect Immun. 1993;61(3):1033. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.3.1033-1039.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoess A, Watson S, Siber GR, Liddington R. EMBO J. 1993;12:3351. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06008.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuppermann N, Nelson DS, Saladino RA, Thompson CM, Sattler F, Novitsky TJ, Fleisher GR, Siber GR. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:630. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.3.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nelson D, Kuppermann N, Fleisher GR, Hammer BK, Thompson CM, Garcia CT, Novitsky TJ, Parsonnet J, Onderdonk A, Siber GR, Saladino RA. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:92. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199501000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garcia C, Saladino R, Thompson C, Hammer B, Parsonnet J, Wainwright N, Novitsky T, Fleisher GR, Siber G. Crit Care Med. 1994;22:1211. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199408000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saladino R, Garcia C, Thompson C, Hammer B, Parsonnet J, Novitsky T, Siber G, Fleisher G. Circ Shock. 1994;42:104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46:3. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rishton GM. Drug Discovery Today. 1997;2:382. doi: 10.1016/s1359644602025722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taylor R, Mullier GW, Sexton GJ. J Mol Graph. 1992;10:152. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(92)80049-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patterson,D.E., Ferguson,A.M., Cramer,R.D., Garr,C.D., Underiner,T.L., and Peterson,J.R. (1997). Design of a Diverse Screening Library. In: High Throughput Screening - The Discovery of Bioactive Substances. In High Throughput Screening - The Discovery of Bioactive Substances, J.P.Devlin, ed. (New York: Marcel-Dekker), pp. 243–250.

- 51.Zhang JH, Chung TD, Oldenburg KR. J Biomol Screen. 1999;4:67. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Green LC, Wagner DA, Glogowski J, Skipper PL, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR. Anal Biochem. 1982;126:131. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Greiss P. Chem Ber. 1879;12:426. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scudiero DA, Shoemaker RH, Paull KD, Monks A, Tierney S, Nofziger TH, Currens MJ, Seniff D, Boyd MR. Cancer Res. 1988;48:4827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roehm NW, Rodgers GH, Hatfield SM, Glasebrook AL. J Immunol Methods. 1991;142:257. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90114-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blagbrough IS, Geall AJ, David SA. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2000;10:1959. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00380-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.David, S. A. and Morrison, D. C. US Patent: Use of synthetic polycationic amphiphilic substances with fatty acid or hydrocarbon substituents as anti-sepsis agents. [5,998,482]. 1999. 11–10–1998.

- 58.Tomalia DA, Naylor AM, Goddard WAII. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1990;29:138. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Velaquez-Campoy A, Todd MJ, Freire E. Biochemistry. 2000;39:2207. doi: 10.1021/bi992399d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Todd MJ, Luque I, Velaquez-Campoy A, Freire E. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11876. doi: 10.1021/bi001013s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]