Abstract

Genomic DNA sequence analysis of the uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain CFT073 revealed that besides the fimB and fimE recombinase genes that control the type 1 pilus fim phase switch, there are three additional fimB- and fimE-like genes: ipuA, ipuB, and ipbA. Alignment of the predicted amino acid sequences showed that the five recombinases range in sequence similarity from 63 to 70%. An epidemiological survey indicates that ipuA and ipuB are present and linked next to the dsdCXA locus in 24 of 67 uropathogenic E. coli strains but are found in only 1 of 15 normal human fecal isolates. The ipbA sequence located next to the betABIT locus was found in 42 of 67 uropathogenic isolates and 8 of 15 of the commensal strains. We show that two of these recombinases, those encoded by ipuA and ipbA, can function at the type 1 pilus fim switch. In a CFT073 deletion mutant lacking all five recombinase genes, recombinant ipuA or ipbA provided in trans inverted the fim element from the off state to the on state. When a fim OFF CFT073 ΔfimBE mutant was used to infect the urinary tracts of mice, a switch to the fim on state was detected within 24 h in bacteria recovered from urine, the bladder, and the kidneys. A fim OFF CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuB ipbA mutant also demonstrated the ability to switch from the fim off state to the on state during mouse infection. CFT073 recombinase mutants derived from isolates in either the fim on or off state showed a reciprocal relationship for motility. Switches from a nonmotile to a motile phenotype and from a fim on to off genotype were observed in fim ON CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA mutants when ipuA or fimB was provided in trans. Together these results indicate that ipuA has fimB-like on-to-off and off-to-on fim switching activity and that ipbA has the ability to switch fim from the off to the on orientation.

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are one of the most common causes of physician visits in the United States. Over 7 million cases of acute cystitis and 250,000 cases of pyelonephritis occur annually, accounting for over 100,000 hospitalizations and an estimated cost of $1.6 billion (8, 19, 20, 32, 49). More than 80% of all UTIs are due to Escherichia coli, causing substantial morbidity and mortality, particularly from the risk of sepsis during pyelonephritis (19, 32, 75). Adherence is generally considered one of the first steps in the initiation of infection, and for uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) that is generally accomplished by type 1 fimbriae (37). Adhesin mutants along with a few mutants of other critical gene products (CNF-1, hemolysin, IrgA, Sat, TonB, DegS, and capsule and full-length lipopolysaccharide) show attenuation in murine models of UTI (6, 14, 28, 35a, 39, 50, 57, 58, 72, 76).

Type 1 fimbriae, which are common to nearly all UPEC strains, bind to mannose-containing glycoproteins on a variety of host cells, including the bladder epithelium, via the fimbrial adhesin (38, 41, 44, 52). While being important for adhesion, the fimbriae may also have a specific role in binding to and invading uroepithelial cells (7, 11, 48, 51, 52). The fimbriae undergo phase variation by the inversion of a 314-bp DNA element (fim switch), which contains the promoter for the main structural subunit, fimA (1, 18, 40, 55). This allows (“on” orientation) or prevents (“off” orientation) transcription of the structural genes. The orientation of the invertible element is controlled by at least two site-specific recombinases, FimB and FimE (40). FimB has the ability to turn the switch in either direction, while FimE can only turn the switch from the on to the off orientation (23, 40, 42).

The FimBE site-specific recombinases are 48% identical in amino acid sequence and are classified as tyrosine or lambda site-specific integrases. There is a tetrad of conserved residues (Arg-47, His-141, Arg-144, and Tyr-176 in FimB of E. coli K-12) that are thought to be the catalytic amino acids (2, 5, 10, 12, 65). FimBE is grouped as a subfamily of recombinases with Mrp of Proteus mirabilis and similar Fim recombinases of other species (46, 54). The closest related subfamily of the tyrosine recombinases is that of the Xer resolvases, which are important for the stable maintenance of some plasmids and chromosomes by resolving multimers to monomers (18, 73). Other lambda integrases are important for phage life cycle, transposition, or other functions within both prokaryotes and yeast (43, 45, 54, 74, 79). Because of their role in phages and other mobile genetic elements, the integrases also play an important role in lateral gene transfer, such as in the she pathogenicity island of Shigella flexneri (61).

The regulation of fimE and fimB is controlled by a variety of regulatory factors (10). Integration host factor, Leucine-responsive protein (Lrp), H-NS, RpoS, the nucleotide sequence of the invertible element, and other factors play a role in the regulation of the fim switch recombinases or the specificity for the on or off orientation (for a review and references, see reference 10). Furthermore, FimBE recombination is influenced by temperature (17, 22, 24); isoleucine, valine, leucine, and alanine (22, 59); osmolarity and pH (64); and culture conditions (63).

There is a report of an off-to-on inversion of the fim switch not mediated by FimE in a natural fimB null strain; however, this observation has not been described further nor have any E. coli recombinases besides FimBE been shown to invert the fim switch (69). When the genome of the pyelonephritis and sepsis isolate CFT073 was sequenced, it was noted that there were three additional fim-like recombinases, in addition to fimB and fimE (76). Relative to the MG1655 K-12 genome map, two of these genes are located in tandem at the 53′ position, and the third is at 7′. Although located at a site distant from the additional CFT073 recombinase genes, the fim switch (98′) provided a starting point for our functional analyses to see whether the three additional recombinases could invert the fim switch. We demonstrate by both in vitro methods and the murine model of ascending urinary tract infection that at least one of these recombinases is capable of inverting the fim switch from the off to the on orientation. We also demonstrate that isolates of E. coli strain CFT073 that originate when fim is in the on position are nonmotile, whereas the fim OFF isolates are motile. In the CFT073 fim ON recombinase deletion mutant, fimB, fimE, and one of the newly described fimBE-like genes mediate a change from a nonmotile to a motile phenotype associated with an on-to-off switch in the fim state. In furtherance of a possible role in E. coli uropathogenesis, the two recombinases near 53′ are shown in an epidemiological survey to occur more frequently among uropathogenic E. coli isolates than among commensal fecal isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Acquisition and naming of recombinase sequences.

Sequencing and annotation of the genome of CFT073 was described previously by Welch et al. (76). In brief, GLIMMER was used to define open reading frames (62), and predicted proteins were searched against the database by using BLAST (4). A total of five fimBE-like recombinase genes were found in the genome of CFT073 (GenBank accession no. AEO14075). Aside from fimB and fimE, two were found at the region corresponding to 53′ of the E. coli K-12 genome near argW and were named ipuA and ipuB for integrase-like proteins in uropathogenic E. coli. The third is at the 7′ region next to the betABIT genes and was named ipbA for integrase-like protein at the betaine locus. Percent identity and similarity to the known fimBE recombinase genes of E. coli K12 (GenBank accession no. U00096) were determined by using BLASTp (4, 9). Predicted protein sequences were aligned with the known sequences of FimB and FimE in E. coli K-12 (9) using the ClustalW program in MacVector 7.2.2 (Accelrys Inc.) to identify the presence of the four catalytic amino acids known to be important for the lambda family of site-specific recombinases (10).

Strains.

Table 1 provides a summary of the strains and plasmids used in this study. Uropathogenic E. coli strain CFT073 was isolated from the blood and urine of a woman admitted to the University of Maryland Medical System for acute pyelonephritis (50). Deletion mutants were made using the λ-red method of recombination described by Datsenko and Wanner (16). The annotated coding sequence of each gene was replaced with either a kanamycin (pKD4) or chloramphenical (pKD3) resistance cassette, which was subsequently eliminated. Further rounds of mutagenesis were used to generate the multiple-deletion constructs. In the construction of one mutant (WAM2901), the standard technique was modified by increasing the length of the homologous sequence. An ipuAB::cam strain was used to generate a DNA fragment with several hundred base pairs of homologous sequence and integrated into the fimBE strain to generate the double mutant. In each construct where fimBE was deleted, colonies were isolated and screened by PCR and asymmetrically digested by SnaBI to determine the orientation of the fim switch, as described previously by Lim et al. (47). The expression of type 1 fimbriae was confirmed by guinea pig erythrocyte agglutination (60). In order to construct strains with the individual recombinases provided in trans, PCR products corresponding to full-length fimB, fimE, ipuB, and ipbA, including their Shine-Dalgarno sites were cloned into the PstI-BamHI sites of pACYC177 (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA). A PCR product corresponding to ipuA was cloned into the KpnI-XbaI sites of pBAD30 (29). TripleMaster (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) and ExTaq (Mirus, Madison, WI) polymerases were used throughout the study. The DNA sequence for each recombinant recombinase was determined to confirm its identity. Restriction enzymes were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI) or New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| WAM2266 | CFT073 Nal; urosepsis isolate | 46 |

| WAM2727 | fim switch locked on | 22 |

| WAM2728 | fim switch locked off | 22 |

| WAM2763 | CFT073 Nal ipuA | This study |

| WAM2764 | CFT073 Nal ipuB | This study |

| WAM2848 | CFT073 Nal ipbA | This study |

| WAM2849 | CFT073 Nal fimBE (type 1 fimbriae on) | This study |

| WAM2958 | CFT073 Nal fimBE (type 1 fimbriae off) | This study |

| WAM2921 | CFT073 Nal fimBE ipbA ipuAB (type 1 fimbriae on) | This study |

| WAM2920 | CFT073 Nal fimBE ipbA ipuAB (type 1 fimbriae off) | This study |

| WAM3038 | CFT073 Nal fimBE ipbA ipuB (type 1 fimbriae on) | This study |

| WAM2986 | CFT073 Nal fimBE ipbA ipuB (type 1 fimbriae off) | This study |

| WAM2925 | CFT073 Nal fimBE ipbA ipuA (type 1 fimbriae on) | This study |

| WAM2924 | CFT073 Nal fimBE ipbA ipuA (type 1 fimbriae off) | This study |

| WAM2901 | CFT073 Nal fimBE ipuAB (type 1 fimbriae on) | This study |

| WAM2959 | CFT073 Nal fimBE ipuAB (type 1 fimbriae off) | This study |

| WAM3122 | WAM2920 with pWAM2770 | This study |

| WAM3123 | WAM2920 with pWAM2775 | This study |

| WAM3124 | WAM2920 with pWAM2961 | This study |

| WAM3125 | WAM2920 with pWAM2801 | This study |

| WAM3126 | WAM2920 with pWAM2957 | This study |

| WAM3127 | WAM2921 with pWAM2770 | This study |

| WAM3128 | WAM2921 with pWAM2775 | This study |

| WAM3129 | WAM2921 with pWAM2961 | This study |

| WAM3130 | WAM2921 with pWAM2801 | This study |

| WAM3131 | WAM2921 with pWAM2957 | This study |

| WAM3608 | WAM2920 with pWAM3579 | |

| WAM3609 | WAM2920 with pWAM3580 | |

| WAM3610 | WAM2921 with pWAM3579 | |

| WAM3611 | WAM2921 with pWAM3580 | |

| Plasmids | ||

| pKD46 | Lambda-Red recombinase helper plasmid | 16 |

| pKD3 | cat+ template plasmid | 16 |

| pKD4 | kan+ template plasmid | 16 |

| pCP20 | FLP helper plasmid | 16 |

| pACYC177 | Low-copy-number cloning plasmid | New England Biolabs |

| pBAD30 | Arabinose-inducible low-copy-number cloning plasmid | 29 |

| pWAM2801 | pACYC177, fimB; Knr | This study |

| pWAM2957 | pACYC177, fimE; Knr | This study |

| pWAM2770 | pBAD30, ipuA; Carr | This study |

| pWAM2775 | pACYC177, ipuB; Knr | This study |

| pWAM2961 | pACYC177, ipbA; Knr | This study |

| pWAM3579 | pACYC184, ipuA; Cmr | This study |

| pWAM3580 | PACYC184, ipuB; Cmr | This study |

Media and growth conditions.

Cultures were routinely grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth with shaking or on LB agar (Difco, Sparks, MD) at 37°C. Kanamycin (50 μg/ml), chloramphenical (20 μg/ml), carbenicillin (250 μg/ml), or l-arabinose (0.02%) were added as appropriate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The in vitro growth conditions for complementation studies or for PCR-based fim switch assays were growth in LB agar and broth without shaking. The orientation of the fim switch was examined for each recombinase mutant after growth in various media which included LB broth, LB agar, MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) minimal agar or broth medium [3-(N-morpholino)propanesulphonic acid supplemented with 0.4% glycerol or glucose] (53), or human urine. MOPS glycerol broth and agar medium were also supplemented with 500 μg/ml d-serine; 50 mM mannose; isoleucine (0.4 mM), leucine (0.8 mM), and valine (0.6 mM); 1 mM choline chloride; 1 mM betaine monohydrate; and 0.6 M NaCl with and without 1 mM choline or betaine (all from Sigma, St. Louis, MO). In addition, the following conditions for LB broth growth were examined: aeration, room temperature, and 42°C, all with or without 500 μg/ml d-serine.

Southern hybridizations.

Chromosomal DNA was prepared from 67 uropathogenic isolates by using the Promega genomic DNA isolation kit (Madison, WI), and 15 normal fecal E. coli isolates were obtained as generous gifts from James R. Johnson (34-36) and Ann Stapleton (26, 61), respectively. DNA was digested with PshAI and SacI blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane using standard techniques. Probes were prepared from the predicted full-length coding sequences of ipuA, ipuB, and ipbA and labeled with [α-P32] using the Prime-It Rm T random primer labeling kit (Stratagene). Blots were visualized on a Typhoon Imager 8600 phosphoimager.

Assays for fim switch orientation.

The assay described by Lim et al. was used to determine the orientation of the fim switch (47). Briefly, chromosomal DNA was prepared and used as template for PCR around the invertible element using primers 5′-CAGTAATGCTGCTCGTTTTGCCG-3′ and 5′-GACAGAGCCGACAGA ACAACG-3′ to generate a 601-bp product. It was digested with SnaBI to yield asymmetric products that differ between the on (403 and 198 bp) and off (440 and 161 bp) fim orientations. After separation in 2% agarose electrophoretic gels, products were visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Lim et al. previously reported that for this assay, the lower limit of sensitivity to detect both on and off orientations is approximately 2% of the minority orientation (47).

Inverse PCR was also used to examine the orientation of the fim switch. Chromosomal DNA was prepared as described above. The template was standardized by adding 100 ng of genomic DNA to a 25-μl reaction mixture. The concentration of the genomic DNA was determined by taking the average of triplicate measurements made using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Rockland, DE). Two reactions were carried out for each DNA sample. The outside primer was 5′-CGACAGCAGAGCTGGTCGCTC-3′, and the two inside primers were 5′-GTAAATTATTTCTCTTGTAAATTAATTTCACATCACCTCCGC-3 (detects fim in the off orientation) and its reverse complement (detects fim in the on orientation). Conditions for PCR were 94°C for 2 min and 25 cycles of 94°C for 20 seconds, 62.5°C for 20 seconds, and 72°C for 1 min. Ten twofold dilutions from 1 ng to approximately 0.002 ng of genomic DNA in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, isolated from WAM2920 (recombinase negative, fim off) and WAM2921 (recombinase negative, fim on) were used to determine the limit of detection for the assay.

Mouse infections.

Swiss-Webster female mice, 6 to 8 weeks old (Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI), were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation and transurethrally inoculated with a catheter and syringe. The inocula were prepared from LB broth cultures grown at 37°C for 18 h without shaking. The cells were centrifuged at 7,500 rpm for 2 min, and pelleted cells were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Each mouse was inoculated with 50 μl of the suspension containing approximately 108 bacteria. In any individual experiment, five or six mice per strain were inoculated. Urine was pooled from those infected with the same strain at approximately 6, 24, and 48 h postinoculation into 500 μl of PBS. Samples were plated for enumeration. The remaining portion of the samples was centrifuged in a microfuge for 2 min, and pelleted cells were suspended in 20 μl of 10 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.0 (Sigma), and frozen at −80°C. These preparations were used as a template for PCR directly from the urine. The orientation of the fim switch was determined by the SnaBI assay.

Following enumeration of the colony-forming units from urine, colonies were swabbed and cells were suspended in 1 ml of PBS. Chromosomal DNA was isolated from these cells, and the orientation of the fim switch was determined by the SnaBI assay. All mouse infections were performed from two to four times per strain investigated.

Motility assay.

An adaptation of the swimming-in-agar assay described by Wolfe and Berg was used to study the motility of CFT073 and its mutant derivatives (77). The medium consists of 1% tryptone, 0.5% NaCl, and 0.3% agar. The different strains were grown to mid-log phase in static LB broth, at which point 1.0 μl of the bacterial suspension was removed and used to inoculate the soft agar medium. The inoculation was accomplished by puncturing the agar surface with the tip of a micropipette. The plates were then incubated at 37°C for 8 to 10 h. Digital pictures of the rings of motile cells were made with the plate sitting on a black fabric background that was illuminated with oblique incandescent light.

RESULTS

Identification of five fimBE-like recombinase genes in CFT073.

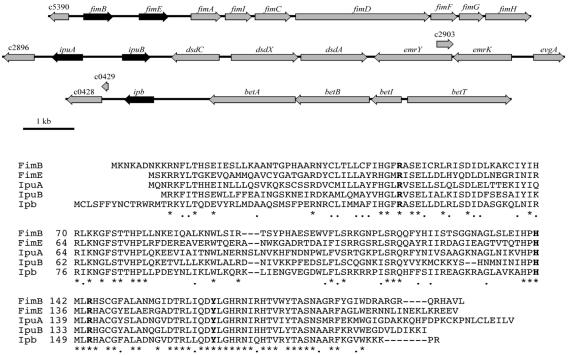

Analysis of the genome of urosepsis isolate CFT073 led to the identification of three additional fimBE-like site-specific recombinase genes that were found based on amino acid sequence similarity to the two known fimBE recombinase genes of E. coli K-12 (9, 76). Two divergently transcribed recombinase gene homologues with a large 758-nucleotide intergenic region are adjacent to the d-serine deaminase locus (dsdCXA) (Fig. 1). They have been designated IpuA (48% identical, 66% similar to FimB) and IpuB (49% identical, 63% similar to FimB) (60). The remaining recombinase is adjacent to the choline-glycine betaine locus (betABIT) (Fig. 1). It has been designated IpbA (55% identical, 70% similar to FimB). For comparison, FimB is 48% identical and 68% similar to FimE. Alignments of the amino acid sequences from the three recombinase homologues were compared to the known sequences of FimB and FimE (Fig. 1). It was determined that all four of the catalytic residues known to be important for the lambda family of site-specific recombinases (i.e., Arg-47, His-141, Arg-144, and Tyr-171 for FimB) were conserved in all of the recombinases found in CFT073 (2, 5, 10, 21, 30, 56).

FIG. 1.

The CFT073 genetic maps (top) and predicted protein alignments (bottom) of fimBE and the three fimBE-like recombinases, ipuA, ipuB, and ipbA. Boldface residues in the alignment represent the four catalytic amino acids for tyrosine recombinases. Asterisks represent identical amino acids, while periods represent similar amino acids. Dashes within a sequence indicate gaps used to maximize alignment.

Southern analysis.

The prevalence of the three fimBE-like recombinase genes was investigated by DNA-DNA hybridization analysis of uropathogenic (34-36) and commensal (68) strains of E. coli. ipuA and ipuB were always found associated with each other and linked to the dsdCXA locus (data not shown). They occurred in 24 of 67 (36%) uropathogenic strains and in only 1 of 15 (7%) commensal strains. The remaining recombinase, ipbA, was more frequently found in the survey and not necessarily associated with the presence of ipuAB. It occurred in 42 of 67 (63%) uropathogenic strains and 8 of 15 (53%) commensal strains. E. coli K-12 strain MG1655 has only fimB and fimE. Under the conditions used for hybridization, no cross-hybridization of specific recombinase probes to the other recombinase genes was evident.

fim switching in vitro.

The ability of ipuA, ipuB, and ipbA to invert the fim switch was evaluated by several approaches. The first method provided each of the five recombinase genes (including fimB and fimE) in trans in a background strain that had all five recombinases deleted and where the fim switch was in either the off or on orientation (WAM2920 and WAM2921, respectively). This approach would determine whether the recombinases were able to invert the fim switch when constitutively overexpressed. With the exception of ipuA, there was no difficulty cloning the recombinase genes downstream of the kanamycin resistance gene in pACYC177. Cells harboring ipuA cloned into that site on pACYC177 grew as long filaments in broth medium. To avoid this complication in our studies ipuA was cloned in two additional forms. First, ipuA was cloned into pBAD30 to make pWAM2770 in order to put ipuA expression under inducible transcriptional control via the arabinose promoter. Second, ipuA and ipuB were independently cloned with their large, 758-nucleotide upstream portions intact into the HindIII site of pACYC184 (pWAM3579 and pWAM3580, respectively). Such constructions would preclude involvement of the vector tetracycline resistance promoter in recombinase expression. Strains harboring pWAM3597 grew as normal rod-shaped cells in broth culture.

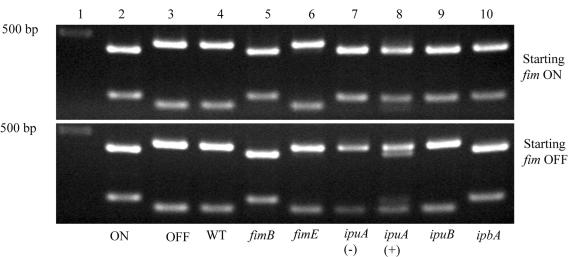

The various strains with fim in the off orientation were assayed for the orientation of their invertible element using the SnaBI digest assay after overnight growth in LB broth. The strains with all five recombinases deleted (WAM2920 and WAM 2921) did not have any detectable change in the starting orientation of the fim switch. When ipuA, ipbA, or fimB was provided in trans, switching from the off to the on orientation was observed (Fig. 2). No such switching from the off to the on orientation was observed when ipuB or fimE alone was provided in trans.

FIG. 2.

The ipuA and ipbA genes function in trans at the fim switch. Ethidium bromide-stained agarose electrophoretic gels containing various SnaBI-digested fim switch PCR products are shown. Lanes 1 to 4 contain the DNA size standard and PCR products from CFT073 fim locked on (WAM2727) (labeled ON), CFT073 fim locked off (WAM2728) (labeled OFF), and CFT073 (WAM2266) (labeled WT) strains, respectively. Lanes 5 to 10 contain PCR products from the CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA fim ON (top panel) and CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA fim OFF (bottom panel) backgrounds transformed with recombinant plasmids carrying the respective recombinase genes listed along the bottom panel. The ipuA(−) and ipuA (+) designations refer to absence or presence of arabinose induction for the ipuA recombinant plasmid pWAM2770 based on the pBAD30 vector. Not shown, but where no switching was observed, are fim OFF WAM2920 and fim ON WAM2921, controls in which all five recombinases are deleted.

Asymmetrical restriction analysis with SnaBI was also used to screen various growth conditions for induction of the fim inversion in strains with the recombinase genes at their native cis sites. The wild type (WAM2266), the fim ON CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA and fim OFF CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA mutants (WAM2921 and WAM2920, respectively), and the fim ON CFT073 ΔfimBE and fim OFF CFT073 ΔfimBE mutants (WAM2849 and WAM2958, respectively) were investigated. Conditions that have been previously documented to influence the orientation of the invertible element under fimBE control in E. coli K-12 were tested. These include variations in temperature (room temperature, 37°, and 42°) (17, 22), growth on liquid and solid media (22, 63), presence of aliphatic amino acids (isoleucine, valine, and leucine) (22), growth in rich and minimal media (22), and variations in osmotic conditions (64). In addition, conditions relevant to UTIs or that were of particular interest due to the chromosomal context of the recombinase genes were investigated. These include growth in human urine, minimal and rich media supplemented with d-serine, minimal media with glycine betaine, and choline chloride; and at high-osmolarity conditions with and without glycine betaine and choline. Within the detection limits of the SnaBI assay, none of these conditions were found to induce inversion of the fim switch from its starting position in a fimBE-independent manner.

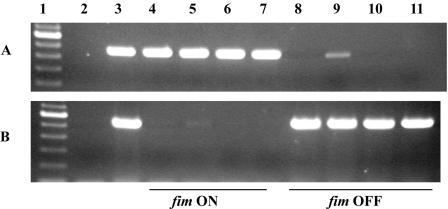

Because of the limited sensitivity of the SnaBI assay, an inverse PCR technique was then used to detect possible inversion at lower frequencies in strains where fimBE was deleted. In two separate reactions, one of two primers inside the invertible element and one outside were used. To estimate the lower limit of detection, twofold dilutions of chromosomal DNA from strains with all recombinases deleted in the on (WAM2921) or off (WAM2920) fim orientation were used as templates. The limit of detection for the off orientation was 0.125 ng of template DNA, while the limit for the on orientation was 0.008 ng of template DNA (data not shown). Strains with four out of the five recombinases deleted were evaluated for fim switching using this method. For the strain that had only ipuA remaining and started in the fim off orientation (WAM2986), we observed bands in the PCRs representing both fim off and fim on orientations (Fig. 3, lane 9). This was not observed with the other strains where just ipuB or ipbA remained at the cis position. Therefore, ipuA, in its native location in the CFT073 chromosome, appears to have the ability to invert the fim switch from off to on during in vitro growth in broth.

FIG. 3.

Inverse PCR detection of the on and off orientations of the CFT073 fim switch. A picture of an ethidium bromide-stained agarose electrophoretic gel containing PCR products is shown. Lanes: 1, the DNA size standard; 2, a nontemplate PCR control; 3, CFT073 (WAM2266); 4, fim ON CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA (WAM2921); 5, fim ON CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuB ipbA (WAM3038); 6, fim ON CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuA ipbA (WAM2925); 7, fim ON CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB (WAM2901); 8, fim OFF CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA (WAM2920); 9, fim OFF CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuB ipbA (WAM2986); 10, fim OFF CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuA ipbA (WAM2924); 11, fim OFF CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB (WAM2959).

fim switching in murine UTI.

To investigate whether CFT073 can invert the fim switch in vivo in a fimBE-independent manner, fim OFF CFT073 ΔfimBE (WAM2958) was used to infect mice in the ascending UTI model. Bacteria harvested from relevant tissues and urine were analyzed for the physical state of the fim switch by the SnaBI digest assay. At 6 and 12 h hrs postinfection, bacteria isolated from the urine of the infected mice remained in the fim off phase, but at 24 h they were comprised of a mixture of on and off fim states (Fig. 4). By 36 h postinoculation, all bacteria isolated from the urine were in the fim on orientation. Bacteria recovered from bladders of infected mice at 72 h (Fig. 4) were in the fim switch on orientation while those from the kidneys were a mixture of fim on and off states. We observed the same fim state pattern in these tissues as early as 48 h (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

In vivo off-to-on switching of fim OFF CFT073 ΔfimBE. Shown in the three panels are ethidium bromide-stained agarose electrophoretic gels containing various SnaBI-digested fim switch PCR products derived from DNA harvested from urine, bladders, and kidneys of infected mice. The first three lanes from left to right contain the DNA size marker and the SnaBI digest of the fim switch PCR product derived from CFT073 fim locked on (WAM2727) and CFT073 fim locked off (WAM2728). The remaining lanes contain the SnaBI digests from the three strains listed to the right: fim ON CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA (WAM2921), fim OFF CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA (recombinase-negative controls), and fim OFF CFT073 ΔfimBE (WAM2958). DNA was extracted from urine, bladders, or kidney samples that were pooled from four to six infected mice. Along the bottom are the postinfection times at which urine was harvested, including the input inocula labeled as INOC. At the far right are SnaBI-digested fim switch PCR products taken from DNA extracted from bladders (B) and kidneys (K) at 72 h postinfection.

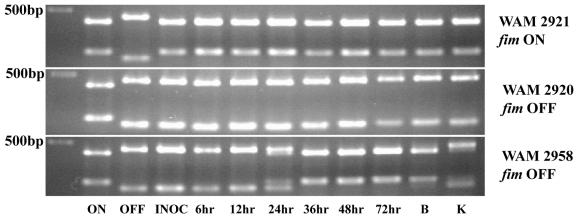

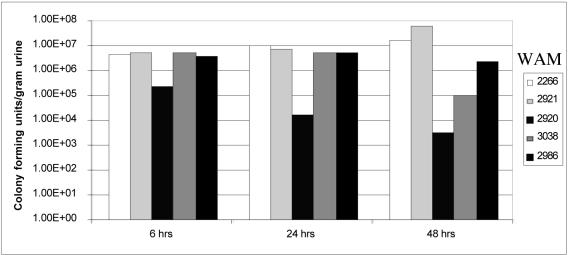

Mutant strains with four of the five recombinases deleted in the fim on and off backgrounds were then examined in the mouse UTI model to determine which of the fimBE-like recombinases are responsible for the in vivo off-to-on fim switch. Urine was collected, and bacteria were enumerated at 6, 24, and 48 h postinoculation. Bacteria direct from the urine, in addition to the bacteria plated for enumeration, were evaluated for the orientation of the fim switch using the SnaBI digest assay. Although plating of bacteria after collection in urine may provide selection for the fim off state, CFT073 strains deleted for fimBE in the fim on state do not undergo inversion to the fim off state as measured by the SnaBI digest assay after overnight growth on LB agar plates (data not shown). Infection of mice with wild-type CFT073 resulted in a sustained level of bacterial shedding of approximately 107 CFU/g urine at 6, 24, and 48 h postinoculation (Fig. 5). When inoculated with various fim ON strains where fimBE are deleted, the mice shed bacteria in numbers equal to or greater than the wild-type strain. However, when all five recombinase genes were deleted and the fim switch was in the off orientation (WAM2920), the number of bacteria shed in the urine decreased approximately 10-fold compared to strains in the fim on orientation at 6 h and approximately 1,000-fold at 48 h after challenge. In infections with WAM2986, the fim OFF CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuB ipbA mutant where ipuA alone remains, bacteria are shed in numbers 100 to 1,000 times greater than fim OFF CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA (WAM2920). The ability of ipuA to cause a fim off-to-on switch in mice was observed in two independent experiments (Fig. 5). Similar results were not observed for fim OFF strains where either ipuB (WAM2924) or ipbA (WAM2959) remained alone in the chromosome.

FIG. 5.

Quantification of bacteria from urine of infected mice. Urine samples were pooled from four to six mice infected with CFT073 (WAM2266), fim ON and OFF controls of recombinase-negative CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA (respectively WAM2921 and WAM2920), and fim ON and OFF CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuB ipbA strains with ipuA alone (WAM3038 and WAM2986). Urine was collected in preweighed tubes with 500 μl of PBS and enumerated on LB plates. Histogram bars represent numbers of colony-forming units per gram of urine. This graph is from a single experiment but is representative of two to four experiments for each of these strains.

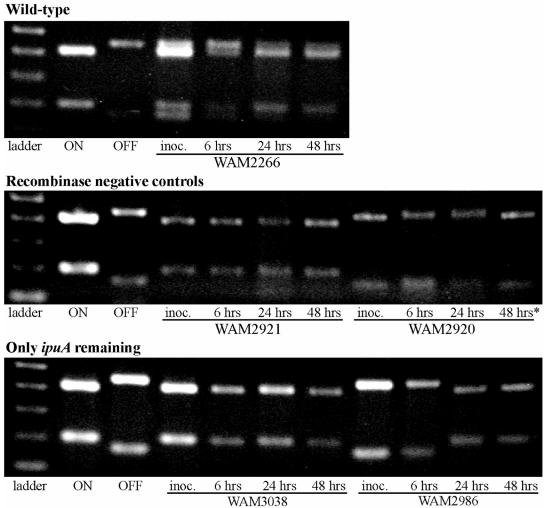

The inocula, as well as the bacteria shed at 6, 24, and 48 h postinoculation in these experiments, were assayed by the SnaBI digest assay for the orientation of the fim switch (Fig. 6). In all cases, the inocula and the bacteria collected at 6 h were shown to have the same fim orientation as the starting strain. Also, for strains with fimBE deleted that started with fim in the on orientation, no switching to the off orientation was observed at any time, whether when the bacteria were taken directly from the urine or after the urine was plated onto LB plates and bacteria were grown overnight. Wild-type CFT073 appeared to be a mixed fim ON/OFF population at all time points during the infection, including the inoculum, but switched to fim OFF if plated onto LB agar (data not shown). Strain WAM 2986, where only ipuA remains and the fim switch is in the off orientation, changed to the fim on orientation at 24 and 48 h postinoculation in two independent experiments (Fig. 6C).

FIG. 6.

ipuA alone can mediate the fim off-to-on switch in vivo. Shown in the three panels are ethidium bromide-stained agarose electrophoretic gels containing various SnaBI-digested fim switch PCR products derived from DNA extracted from infected mouse urine. The first three lanes from left to right contain the DNA size marker and the SnaBI digest of the fim switch PCR product derived from digest controls of CFT073 fim locked on (WAM2727) and CFT073 fim locked off (WAM2728). The orientation of the fim switch in bacteria in pooled urine from mice infected with CFT073 (WAM2266) (top panel), CFT073 recombinase negative fim ON and OFF controls (WAM2921 and WAM2920) (middle panel), and CFT073 strains where only ipuA remains in backgrounds of fim on and off orientations (WAM3038 and WAM2986) (bottom panel). The figure is representative of the results from at least two separate experiments. In one experiment, WAM2986 was observed to be a mixed ON/OFF population at 24 h postinoculation. The experiment with WAM2920 was conducted four times. For this strain alone, a PCR product was not obtained directly from DNA in the urine at 48 h postinoculation, although bacteria were detected by growth in the urine on LB plates. Therefore, the WAM2920 PCR product at 48 h was obtained from DNA taken from colonies on the LB agar.

fim switching and motility.

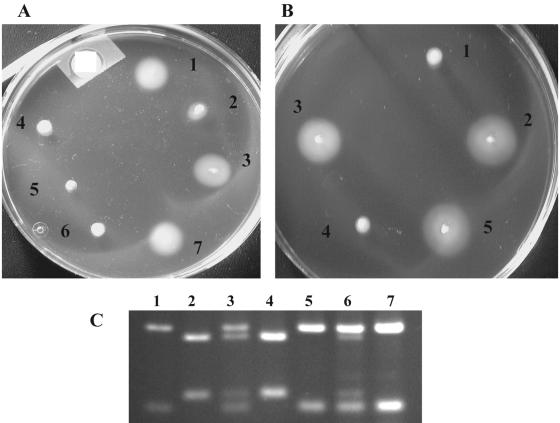

A reciprocal relationship between motility and expression of fimbriae or adherence phenotypes has been observed for Vibrio cholerae, Bordetella pertussis, Proteus mirabilis, and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (3, 13, 25, 46). We examined motility for the various CFT073 recombinase mutants in both the fim switch on and off orientations. CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA (WAM2921) and CFT073 ΔfimBE (WAM2849) are nonmotile in a soft agar swimming motility assay when the fim switch is on (Fig. 7A), whereas the same deletion mutants in the fim switch off state are motile in the assay. In this study we also used the CFT073 fim switch “locked-on” and “locked-off” mutants previously isolated by Gunther et al. (27). The motility phenotypes of these two mutants were similar to their fim on and off counterparts derived here although the fim locked-off mutant shows a smaller zone of motile cells than that typically seen with the other fim OFF strains (Fig. 7A). The ability of the different recombinases in trans to switch the phenotype of a nonmotile, fim switch on to a motile fim off state was investigated. The motility assay revealed that ipuA but not ipuB or ipbA (data not shown) can mediate the change in motility phenotype associated with the fim switch on-to-off inversion. The change to the motile phenotype was also associated with an on-to-off change in the orientation of the fim element (Fig. 7C).

FIG. 7.

Reciprocal status of motility and type 1 pilus expression in CFT073. Shown in the top two photographs (A and B) are zones of swimming motility in 0.3% agar tryptone plates. Plate A contains fim OFF CFT073 ΔfimBE (WAM2958) (1); CFT073 fim locked OFF (WAM2728) (2); fim OFF CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA(WAM2920) (3); fim ON CFT073 ΔfimBE (WAM2849) (4); CFT073 fim locked ON (WAM2727) (5); fim ON CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA (WAM2921) (6); CFT073 (WAM2266) (7). Plate B contains fim ON CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA (WAM2921) (1); fim OFF CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA (WAM2920) (2); fim ON CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA/pWAM3579, which encodes ipuA (WAM3610) (3); fim ON CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA/pWAM3580, which encodes ipuB (WAM3611) (4); CFT073 (WAM2266) (5). The bottom photograph (C) shows an ethidium bromide-stained agarose electrophoretic gel containing SnaBI-digested fim switch PCR products from bacterial DNA extracted from cells on motility plates shown in panels A and B. Lanes: 1, CFT073 (WAM2266); 2, fim ON CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA (WAM2921); 3, fim ON CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA/pWAM3579, which encodes ipuA (WAM3610); 4, fim ON CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA/pWAM3580, which encodes ipuB (WAM3611); 5, fim OFF CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA (WAM2920); 6, fim OFF CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA/pWAM3579; 6, fim OFF CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA/pWAM3580.

DISCUSSION

The type 1 fimbriae are a preeminent virulence factor for uropathogenic E. coli, and the genes necessary for fimbria production are among the most highly expressed genes during infection of the mouse urinary tract (67). We have characterized the activity of three previously unrecognized recombinases in E. coli CFT073 that are homologues of the FimBE recombinases that regulate expression of type 1 fimbriae. In this study, we demonstrate that at least one of these recombinase genes, ipuA, is transcriptionally active at its native chromosomal location and has the ability to invert the fim switch in both directions. It has been previously suggested by Gunther et al. that not only is the expression of the fimbriae important for pathogenesis, but its mechanism of control through the orientation of the fim switch also contributes to virulence (27). Due to the importance of the type 1 fimbriae in pathogenesis and the similarity of putative integrases to FimBE, we utilized the fim switch as a model system to investigate the activity of the newly identified recombinases.

The three potential recombinases IpuA, IpuB, and IpbA, share a significant amount of amino acid sequence similarity among themselves as well as to FimB and FimE. The genes probably arose by duplications, as has been hypothesized for fimB and fimE (10, 40). Similarity among the recombinases is highest at the C-terminal region, which contains the catalytic domain (18, 54). This has been observed for all members of the lambda integrase family (54). All three possess the conserved tetrad of residues necessary for activity of the lambda family of site-specific recombinases, which suggests that they possess regulatory roles for gene expression in strain CFT073. The epidemiological survey showed that ipbA was ubiquitous, being found approximately half the time in both commensal fecal and uropathogenic isolates of E. coli. ipuA and ipuB, however, tended to occur more frequently among UPEC strains than in commensal fecal isolates. This observation would be consistent with the hypothesis that they play a role in the regulation of E. coli uropathogenesis.

The ipuA, ipuB, and ipbA genes were used in complementation studies in order to assess their activity at the fim switch. To ensure expression, the CFT073 recombinases were cloned into low-copy plasmids and used to transform CFT073 mutant strains where all five recombinase genes were deleted. ipuA and ipbA, but not ipuB, were able to invert the fim switch from off to on. To determine whether these three genes could function in their native chromosomal configuration, a fim OFF CFT073 ΔfimBE strain was grown under various growth conditions and then assessed for fim off-to-on switching. No environmental condition tested was identified that induced new or more frequent switching by the three genes. ipuA was the only recombinase gene aside from fimB able to invert the fim switch from off to on when at its native location in the chromosome. It is possible that ipuB is not a functional fim recombinase gene and that ipbA only has fim switching ability when overexpressed. We are currently constructing different fim switch reporter and selection systems to futher address the issues of functionality and relative rates of recombinase activity.

A CFT073 fim off-to-on phase switch in the mouse urinary tract was readily mediated in a fimBE-independent manner. Interestingly, bacteria shed in the urine were principally in the fim off phase at 12 h, in a mixture of orientations at 24 h, and mostly in the fim on state at 36 through 72 h. The SnaBI assay revealed that more than 98% of the E. coli cells isolated from the bladder are in the fim on state but concomitantly that a mixture of fim ON and OFF bacteria were isolated from the kidney at the later time points. Our experiments indicate that ipuA probably mediates the fimBE-independent off-to-on fim inversion during infection of the mouse urinary tract. When the fim OFF CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuB ipbA mutant is used as a challenge strain, there is no significant difference between it and wild-type CFT073 with respect to the levels of bacteria recovered from mouse urine over 48 h. IpuA mediates an adequate amount of fim off-to-on switching, such that the selection pressure in the urinary tract probably favors the fim ON cells. While in vivo induction of ipuA expression is a possibility, the experiments cannot distinguish between it and simple in vivo selection of the fim ON strains present in the inoculum. Perhaps IpuA helps tip the balance in favor of the fim on orientation under some unknown condition. At present we do not know how ipuA relates to fimB in terms of mediating the fim off-to-on switch in the CFT073 background. Studies investigating the transcriptional control of ipuA and the relative in vivo induction of expression of all five recombinases are under way.

The expression of type 1 fimbriae during infection has been investigated extensively, including studies that compared differences in fim expression between cystitis- and pyelonephritis-related E. coli isolates (26, 27, 33, 47, 70). We observed over the span of the mouse infection that the orientation of the fim switch in wild-type CFT073 differed from that found in previous studies by another laboratory (27, 47). In our experiments, the broth-grown wild-type CFT073 inoculum was a mixture of fim on and off orientations and remained a mixture in infected urine collected at 6, 24, and 48 h postinoculation. The CFT073 inoculum in the Gunther et al. study was prepared from agar plates and primarily in the fim off orientation with a peak of 33.6% of cells appearing in the fim on orientation at 24 h postinoculation (27). For fim OFF strains with the functional recombinase FimB or IpuA, there is a switch and selection to the fim on state within the bladder by 24 h. However, similar to our results, Gunther et al. observed that bacteria that were recovered from the kidneys of the infected mice appeared to be a mixture of on or off fim phases at 48 h postinoculation. It is known from previous studies and shown again here as well that expression of type 1 fimbriae is not necessary for UPEC infection of the bladder and subsequent infection of the kidneys (27). It is unclear whether the mixed fim expression states we observed represent a switch from fim on to off phases for bacteria while in the kidney or whether bacteria in the fim off state got to that site during the infection by actively ascending the ureter or by vesicoureteral reflux.

Previous observations of an inverse relationship between bacterial motility and expression of adhesins led to our examination of motility among the CFT073 fim ON and OFF recombinase mutants (7, 71). It is known that when CFT073 constitutively expresses type 1 fimbriae there is a decrease in motility but that mutants involved in motility (e.g., fliC, motB, and cheW) do not necessarily upregulate expression of type 1 fimbriae (M. C. Lane, C. V. Lockatell, D. Lamphier, J. Weinert, J. R. Hebel, D. E. Johnson, and H. L. T. Mobley, Abstr. 105th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. B-269, p. 79, 2005). We observed that all of the mutant isolates in the fim off orientation were at least as motile as the wild type with the exception of the CFT073 fim locked-off mutant, which was slightly less motile than the others and the wild type. Conversely, CFT073 isolates in the fim on orientation were nonmotile over the 8- to 10-h incubation time used in our studies. It was also shown by this approach that ipuA is functionally similar to fimB because besides being able to change the fim element from off to on, it can mediate the fim switch from on to off, which was observed here with the gain in motility. Recently, together with the members of the Mobley laboratory, we demonstrated that there is a reciprocal relationship between expression of type 1 fimbriae and the pap fimbriae during CFT073 infections of the mouse urinary tract (66). This relationship among E. coli adhesins in vitro had previously been described by others (31, 78). Our results indicate that the fim switch also controls the inverse expression of type 1 fimbriae and motility. It is possible that while expression of type 1 fimbriae is important in the early stages of infection for UPEC, it is down-regulated as the infection progresses, allowing the expression of motility and P fimbriae for ascension to and colonization of the kidneys. Thismay explain our mouse infection results where at 48 h postinfection, there is an approximately 100-fold reduced but persistent bladder and kidney colonization by the recombinase-negative, fim OFF CFT073 ΔfimBE ipuAB ipbA mutant (WAM2920) compared to wild-type CFT073 or any of the fim ON recombinase mutants. The mechanism whereby motility and P fimbriae are up-regulated with the fim switch in the off orientation is unknown.

In this study, we investigated the activity of three previously unrecognized recombinases by monitoring their ability to invert the type 1 fimbrial phase switch. IpuA clearly behaves like FimB because it can invert the fim switch in either orientation. To our knowledge, this represents the first identification of an E. coli recombinase which causes type 1 fimbrial phase switching in a fimBE-independent manner. Although our results indicate that ipbA has fim off-to-on switching activity, it was only demonstrated in the context of a multicopy recombinant plasmid. Perhaps ipuB or ipbA is functional at the fim switch under conditions different than those studied here. The newly described E. coli recombinases may function at unknown DNA sites within the genome, raising the possibility that many UPEC strains may have additional phase states besides those controlling expression of type 1 and the pap fimbriae. The extra complexity may provide this pathogen with the ability to carry out a cellular diffentiation program compatible with its multistage ascension of the urinary tract. The genetic linkage of these recombinases to and possible regulation of the genes for d-serine utilization (dsdCXA) and choline-glycine betaine metabolism (betABIT) is intriguing because of the previous associations of those E. coli loci with uropathogenesis (15, 61). Specifically, the loss of expression of d-serine deaminase in CFT073 is associated with the gain of a hypermotile state, a change in cellular morphology, and increased ability to colonize the murine urinary tract (60).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Heath Service grants DK63250 and AI01583 (to P.R.) and the Hilldale Undergraduate Research Fellowship and American Society of Microbiology Undergraduate Research Fellowships (to A.B.).

We thank Peter Redford and Brian Haugan for their assistance with the mouse experiments.

Editor: A. D. O'Brien

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham, J. M., C. S. Freitag, R. M. Gander, J. R. Clements, V. L. Thomas, and B. I. Eisenstein. 1986. Fimbrial phase variation and DNA rearrangements in uropathogenic isolates of Escherichia coli. Mol. Biol. Med. 3:495-508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abremski, K. E., and R. H. Hoess. 1992. Evidence for a second conserved arginine residue in the integrase family of recombination proteins. Prot. Eng. 5:87-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akerley, B. J., P. A. Cotter, and J. F. Miller. 1995. Ectopic expression of the flagellar regulon alters development of the Bordetella-host interaction. Cell 80:611-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Argos, P., A. Landy, K. Abremski, J. B. Egan, E. Haggard-Ljungquist, R. H. Hoess, M. L. Kahn, B. Kalionis, S. V. Narayana, L. S. Pierson III, et al. 1986. The integrase family of site-specific recombinases: regional similarities and global diversity. EMBO J. 5:433-440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bahrani-Mougeot, F. K., E. L. Buckles, C. V. Lockatell, J. R. Hebel, D. E. Johnson, C. M. Tang, and M. S. Donnenberg. 2002. Type 1 fimbriae and extracellular polysaccharides are preeminent uropathogenic Escherichia coli virulence determinants in the murine urinary tract. Mol. Microbiol. 45:1079-1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnich, N., J. Boudeau, L. Claret, and A. Darfeuille-Michaud. 2003. Regulatory and functional co-operation of flagella and type 1 pili in adhesive and invasive abilities of AIEC strain LF82 isolated from a patient with Crohn's disease. Mol. Microbiol. 48:781-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergeron, M. G. 1995. Treatment of pyelonephritis in adults. Med. Clin. N. Am. 79:619-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blattner, F. R., G. Plunkett III, C. A. Bloch, N. T. Perna, V. Burland, M. Riley, J. Collado-Vides, J. D. Glasner, C. K. Rode, G. F. Mayhew, J. Gregor, N. W. Davis, H. A. Kirkpatrick, M. A. Goeden, D. J. Rose, B. Mau, and Y. Shao. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blomfield, I. C. 2001. The regulation of pap and type 1 fimbriation in Escherichia coli. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 45:1-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boudeau, J., N. Barnich, and A. Darfeuille-Michaud. 2001. Type 1 pili-mediated adherence of Escherichia coli strain LF82 isolated from Crohn's disease is involved in bacterial invasion of intestinal epithelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1272-1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burns, L. S., S. G. Smith, and C. J. Dorman. 2000. Interaction of the FimB integrase with the fimS invertible DNA element in Escherichia coli in vivo and in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 182:2953-2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clegg, S., and K. T. Hughes. 2002. FimZ is a molecular link between sticking and swimming in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 184:1209-1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connell, I., W. Agace, P. Klemm, M. Schembri, S. Marild, and C. Svanborg. 1996. Type 1 fimbrial expression enhances Escherichia coli virulence for the urinary tract. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:9827-9832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Culham, D. E., C. Dalgado, C. L. Gyles, D. Mamelak, S. MacLellan, and J. M. Wood. 1998. Osmoregulatory transporter ProP influences colonization of the urinary tract by Escherichia coli. Microbiology 144:91-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dorman, C. J., and N. N. Bhriain. 1992. Thermal regulation of fimA, the Escherichia coli gene coding for the type 1 fimbrial subunit protein. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 78:125-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esposito, D., and J. J. Scocca. 1997. The integrase family of tyrosine recombinases: evolution of a conserved active site domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3605-3614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foxman, B., K. L. Klemstine, and P. D. Brown. 2003. Acute pyelonephritis in US hospitals in 1997: hospitalization and in-hospital mortality. Ann. Epidemiol. 13:144-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foxman, B., R. Barlow, H. D'Arcy, B. Gillespie, and J. D. Sobel. 2000. Urinary tract infection: self-reported incidence and associated costs. Ann. Epidemiol. 10:509-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friesen, H., and P. D. Sadowski. 1992. Mutagenesis of a conserved region of the gene encoding the FLP recombinase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. A role for arginine 191 in binding and ligation. J. Mol. Biol. 225:313-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gally, D. L., J. A. Bogan, B. I. Eisenstein, and I. C. Blomfield. 1993. Environmental regulation of the fim switch controlling type 1 fimbrial phase variation in Escherichia coli K-12: effects of temperature and media. J. Bacteriol. 175:6186-6193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gally, D. L., J. Leathart, and I. C. Blomfield. 1996. Interaction of FimB and FimE with the fim switch that controls the phase variation of type 1 fimbriae in Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Microbiol. 21:725-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gally, D. L., T. J. Rucker, and I. C. Blomfield. 1994. The leucine-responsive regulatory protein binds to the fim switch to control phase variation of type 1 fimbrial expression in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 176:5665-5672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gardel, C. L., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1996. Alterations in Vibrio cholerae motility phenotypes correlate with changes in virulence factor expression. Infect. Immun. 64:2246-2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gunther, N. W., IV, J. A. Snyder, V. Lockatell, I. Blomfield, D. E. Johnson, and H. L. T. Mobley. 2002. Assessment of virulence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli type 1 fimbrial mutants in which the invertible element is phase-locked on or off. Infect. Immun. 70:3344-3354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gunther, N. W., IV, V. Lockatell, D. E. Johnson, and H. L. T. Mobley. 2001. In vivo dynamics of type 1 fimbria regulation in uropathogenic Escherichia coli during experimental urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 69:2838-2846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guyer, D. M., S. Radulovic, F. E. Jones, and H. L. T. Mobley. 2002. Sat, the secreted autotransporter toxin of uropathogenic Escherichia coli, is a vacuolating cytotoxin for bladder and kidney epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 70:4539-4546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guzman, L. M., D. Belin, M. J. Carson, and J. Beckwith. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:4121-4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han, Y. W., R. I. Gumport, and J. F. Gardner. 1994. Mapping the functional domains of bacteriophage lambda integrase protein. J. Mol. Biol. 235:908-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holden, N. J., B. E. Uhlin, and D. L. Gally. 2001. PapB paralogues and their effect on the phase variation of type 1 fimbriae in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 42:319-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hooton, T. M., and W. E. Stamm. 1997. Diagnosis and treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infection. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 11:551-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson, D. E., C. V. Lockatell, R. G. Russell, J. R. Hebel, M. D. Island, A. Stapleton, W. E. Stamm, and J. W. Warren. 1998. Comparison of Escherichia coli strains recovered from human cystitis and pyelonephritis infections in transurethrally challenged mice. Infect. Immun. 66:3059-3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson, J. R., I. Orskov, F. Orskov, P. Goullet, B. Picard, S. L. Moseley, P. L. Roberts, and W. E. Stamm. 1994. O, K, and H antigens predict virulence factors, carboxylesterase B pattern, antimicrobial resistance, and host compromise among Escherichia coli strains causing urosepsis. J. Infect. Dis. 169:119-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson, J. R., P. Goullet, B. Picard, S. L. Moseley, P. L. Roberts, and W. E. Stamm. 1991. Association of carboxylesterase B electrophoretic pattern with presence and expression of urovirulence factor determinants and antimicrobial resistance among strains of Escherichia coli that cause urosepsis. Infect. Immun. 59:2311-2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35a.Johnson, J. R., S. Jelacic, L. M. Schoening, C. Clabots, N. Shaikh, H. L. T. Mobley, and P. I. Tarr. 2005. The IrgA homologue adhesin Iha is an Escherichia coli virulence factor in murine urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 73:965-971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson, J. R., P. L. Roberts, and W. E. Stamm. 1987. P fimbriae and other virulence factors in Escherichia coli urosepsis: association with patients' characteristics. J. Infect. Dis. 156:225-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson, J. R. 1991. Virulence factors in Escherichia coli urinary tract infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 4:80-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones, C. H., J. S. Pinkner, R. Roth, J. Heuser, A. V. Nicholes, S. N. Abraham, and S. J. Hultgren. 1995. FimH adhesin of type 1 pili is assembled into a fibrillar tip structure in the Enterobacteriaceae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:2081-2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keith, B. R., L. Maurer, P. A. Spears, and P. E. Orndorff. 1986. Receptor-binding function of type 1 pili effects bladder colonization by a clinical isolate of Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 53:693-696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klemm, P. 1986. Two regulatory fim genes, fimB and fimE, control the phase variation of type 1 fimbriae in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 5:1389-1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krogfelt, K. A., H. Bergmans, and P. Klemm. 1990. Direct evidence that the FimH protein is the mannose-specific adhesin of Escherichia coli type 1 fimbriae. Infect. Immun. 58:1995-1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kulasekara, H. D., and I. C. Blomfield. 1999. The molecular basis for the specificity of fimE in the phase variation of type 1 fimbriae of Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1171-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Landy, A. 1989. Dynamic, structural, and regulatory aspects of lambda site-specific recombination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 58:913-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Langermann, S., S. Palaszynski, M. Barnhart, G. Auguste, J. S. Pinkner, J. Burlein, P. Barren, S. Koenig, S. Leath, C. H. Jones, and S. J. Hultgren. 1997. Prevention of mucosal Escherichia coli infection by FimH-adhesin-based systemic vaccination. Science 276:607-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee, M. H., and G. F. Hatfull. 1993. Mycobacteriophage L5 integrase-mediated site-specific integration in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 175:6836-6841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li, X., C. V. Lockatell, D. E. Johnson, and H. L. T. Mobley. 2002. Identification of MrpI as the sole recombinase that regulates the phase variation of MR/P fimbria, a bladder colonization factor of uropathogenic Proteus mirabilis. Mol. Microbiol. 45:865-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lim, J. K., N. W. T. Gunther, H. Zhao, D. E. Johnson, S. K. Keay, and H. L. Mobley. 1998. In vivo phase variation of Escherichia coli type 1 fimbrial genes in women with urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 66:3303-3310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martinez, J. J., M. A. Mulvey, J. D. Schilling, J. S. Pinkner, and S. J. Hultgren. 2000. Type 1 pilus-mediated bacterial invasion of bladder epithelial cells. EMBO J. 19:2803-2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McCarthy, E. 1982. Inpatient utilization of short-stay hospitals, by diagnosis. Vital Health Stat. 13:1-82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mobley, H. L. T., D. M. Green, A. L. Trifillis, D. E. Johnson, G. R. Chippendale, C. V. Lockatell, B. D. Jones, and J. W. Warren. 1990. Pyelonephritogenic Escherichia coli and killing of cultured human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells: role of hemolysin in some strains. Infect. Immun. 58:1281-1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mulvey, M. A., J. D. Schilling, and S. J. Hultgren. 2001. Establishment of a persistent Escherichia coli reservoir during the acute phase of a bladder infection. Infect. Immun. 69:4572-4579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mulvey, M. A., Y. S. Lopez-Boado, C. L. Wilson, R. Roth, W. C. Parks, J. Heuser, and S. J. Hultgren. 1998. Induction and evasion of host defenses by type 1-piliated uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Science 282:1494-1497. (Erratum, 283:795, 1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Neidhardt, F. C., P. L. Bloch, and D. F. Smith. 1974. Culture medium for enterobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 119:736-747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nunes-Duby, S. E., H. J. Kwon, R. S. Tirumalai, T. Ellenberger, and A. Landy. 1998. Similarities and differences among 105 members of the Int family of site-specific recombinases. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:391-406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Olsen, P. B., and P. Klemm. 1994. Localization of promoters in the fim gene cluster and the effect of H-NS on the transcription of fimB and fimE. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 116:95-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parsons, R. L., P. V. Prasad, R. M. Harshey, and M. Jayaram. 1988. Step-arrest mutants of FLP recombinase: implications for the catalytic mechanism of DNA recombination. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:3303-3310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Redford, P., P. L. Roesch, and R. A. Welch. 2003. DegS is necessary for virulence and is among extraintestinal Escherichia coli genes induced in murine peritonitis. Infect. Immun. 71:3088-3096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rippere-Lampe, K. E., A. D. O'Brien, R. Conran, and H. A. Lockman. 2001. Mutation of the gene encoding cytotoxic necrotizing factor type 1 (cnf1) attenuates the virulence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 69:3954-3964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roesch, P. L., and I. C. Blomfield. 1998. Leucine alters the interaction of the leucine-responsive regulatory protein (Lrp) with the fim switch to stimulate site-specific recombination in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 27:751-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roesch, P. L., P. Redford, S. Batchelet, R. L. Moritz, S. Pellett, B. J. Haugen, F. R. Blattner, and R. A. Welch. 2003. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli use d-serine deaminase to modulate infection of the murine urinary tract. Mol. Microbiol. 49:55-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sakellaris, H., S. N. Luck, K. Al-Hasani, K. Rajakumar, S. A. Turner, and B. Adler. 2004. Regulated site-specific recombination of the she pathogenicity island of Shigella flexneri. Mol. Microbiol. 52:1329-1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Salzberg, S. L., A. L. Delcher, S. Kasif, and O. White. 1998. Microbial gene identification using interpolated Markov models. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:544-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schwan, W. R., H. S. Seifert, and J. L. Duncan. 1992. Growth conditions mediate differential transcription of fim genes involved in phase variation of type 1 pili. J. Bacteriol. 174:2367-2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schwan, W. R., J. L. Lee, F. A. Lenard, B. T. Matthews, and M. T. Beck. 2002. Osmolarity and pH growth conditions regulate fim gene transcription and type 1 pilus expression in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 70:1391-1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smith, S. G., and C. J. Dorman. 1999. Functional analysis of the FimE integrase of Escherichia coli K-12: isolation of mutant derivatives with altered DNA inversion preferences. Mol. Microbiol. 34:965-979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Snyder, J. A., B. J. Haugen, C. V. Lockatell, N. Maroncle, E. C. Hagan, D. E. Johnson, R. A. Welch, and H. L. T. Mobley. 2005. Coordinate expression of fimbriae in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 73:7588-7596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Snyder, J. A., B. J. Haugen, E. L. Buckles, C. V. Lockatell, D. E. Johnson, M. S. Donnenberg, R. A. Welch, and H. L. T. Mobley. 2004. Transcriptome of uropathogenic Escherichia coli during urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 72:6373-6381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stapleton, A., S. Moseley, and W. E. Stamm. 1991. Urovirulence determinants in Escherichia coli isolates causing first-episode and recurrent cystitis in women. J. Infect. Dis. 163:773-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stentebjerg-Olesen, B., T. Chakraborty, and P. Klemm. 1999. Type 1 fimbriation and phase switching in a natural Escherichia coli fimB null strain, Nissle 1917. J. Bacteriol. 181:7470-7478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Struve, C., and K. A. Krogfelt. 1999. In vivo detection of Escherichia coli type 1 fimbrial expression and phase variation during experimental urinary tract infection. Microbiology 145:2683-2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tisa, L. S., and J. Adler. 1995. Chemotactic properties of Escherichia coli mutants having abnormal Ca2+ content. J. Bacteriol. 177:7112-7118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Torres, A. G., P. Redford, R. A. Welch, and S. M. Payne. 2001. TonB-dependent systems of uropathogenic Escherichia coli: aerobactin and heme transport and TonB are required for virulence in the mouse. Infect. Immun. 69:6179-6185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Villion, M., and G. Szatmari. 2003. The XerC recombinase of Proteus mirabilis: characterization and interaction with other tyrosine recombinases. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 226:65-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Waldman, A. S., W. P. Fitzmaurice, and J. J. Scocca. 1986. Integration of the bacteriophage HP1c1 genome into the Haemophilus influenzae Rd chromosome in the lysogenic state. J. Bacteriol. 165:297-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Warren, J. W. 1996. Clinical presentations and epidemiology of urinary tract infections, p. 3-27. In H. L. T. Mobley and J. W. Warren (ed.), Urinary tract infections: molecular pathogenesis and clinical management. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 76.Welch, R. A., V. Burland, G. Plunkett III, P. Redford, P. Roesch, D. Rasko, E. L. Buckles, S. R. Liou, A. Boutin, J. Hackett, D. Stroud, G. F. Mayhew, D. J. Rose, S. Zhou, D. C. Schwartz, N. T. Perna, H. L. T. Mobley, M. S. Donnenberg, and F. R. Blattner. 2002. Extensive mosaic structure revealed by the complete genome sequence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:17020-17024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wolfe, A. J., and H. C. Berg. 1989. Migration of bacteria in semisolid agar. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:6973-6977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xia, Y., D. Gally, K. Forsman-Semb, and B. E. Uhlin. 2000. Regulatory cross-talk between adhesin operons in Escherichia coli: inhibition of type 1 fimbriae expression by the PapB protein. EMBO J. 19:1450-1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yu, A., L. E. Bertani, and E. Haggard-Ljungquist. 1989. Control of prophage integration and excision in bacteriophage P2: nucleotide sequences of the int gene and att sites. Gene 80:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]