Abstract

Saccharomyces cerevisiae protoplasts exposed to bovine papillomavirus type 1 (BPV-1) virions demonstrated uptake of virions on electron microscopy. S. cerevisiae cells looked larger after exposure to BPV-1 virions, and cell wall regeneration was delayed. Southern blot hybridization of Hirt DNA from cells exposed to BPV-1 virions demonstrated BPV-1 DNA, which could be detected over 80 days of culture and at least 13 rounds of division. Two-dimensional gel analysis of Hirt DNA showed replicative intermediates, confirming that the BPV-1 genome was replicating within S. cerevisiae. Nicked circle, linear, and supercoiled BPV-1 DNA species were observed in Hirt DNA preparations from S. cerevisiae cells infected for over 50 days, and restriction digestion showed fragments hybridizing to BPV-1 in accord with the predicted restriction map for circular BPV-1 episomes. These data suggest that BPV-1 can infect S. cerevisiae and that BPV-1 episomes can replicate in the infected S. cerevisiae cells.

Papillomaviruses are a family of more than 130 genotypes of 8-kb double-stranded DNA viruses which utilize the host cell DNA replication machinery, together with at least two virally encoded nonstructural proteins (E1 and E2), to replicate their DNA episomally in squamous epithelium. Efforts to study the virus life cycle and infection pathway have been hampered by the small amounts of virus produced in clinical lesions. Additionally, no in vitro conventional cell culture system is permissive for vegetative reproduction of human papillomavirus (HPV), although viral replication can be achieved with low efficiency for some virus types in epithelial raft culture. Furthermore, no small laboratory animal is host to a characterized papillomavirus infection. Thus, a simple system for studying papillomavirus replication and for production of infectious virions would assist studies on this oncogenic virus.

Papillomavirus-infected tissues display a characteristic papillomavirus gene transcription pattern in individual epithelial layers when examined by in situ hybridization with subgenomic RNA probes (3, 10, 18). Raft culture systems have confirmed that the papillomavirus vegetative life cycle is linked to epithelial differentiation and have shown viral amplification, late-gene expression, and virion production only in differentiated cells (4, 9, 17), though the basis of the restriction on late gene expression and viral replication remains uncertain.

Codon usage in papillomavirus genes more closely resembles that of the yeasts than of the mammalian consensus (26). Considering this, we hypothesized that S. cerevisiae might be a permissive host for at least some part of the papillomavirus life cycle in vitro, as membrane proteins of yeast cells include integrinlike molecules (11), and thus virus uptake via integrins might be expected. Replication of genetic elements in S. cerevisiae is dependent on ARS sequences (13), and there is a 10 of 11 nucleotide match to the consensus ARS sequence within the BPV-1 genome at nucleotide 7097.

To test whether papillomaviruses could be taken up by S. cerevisiae cells, and particularly whether the papillomavirus episome could replicate in S. cerevisiae, we used BPV-1 virions derived from warts. As the S. cerevisiae cell wall might inhibit papillomavirus infection, we studied infection of protoplasts. We report here that S. cerevisiae protoplasts can take up BPV-1 virions and that the BPV-1 genome replicates episomally in S. cerevisiae through many cell divisions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

S. cerevisiae protoplast cultures.

S. cerevisiae strains Y303 and M2915 used in the present experiments were kindly provided by Xin Jie Chen (Research School of Biological Sciences, The Australian National University). S. cerevisiae was cultured in liquid medium with vigorous shaking overnight, and 20 ml of S. cerevisiae culture, at 108 cells/ml, was harvested by centrifugation at 2,500 rpm for 10 min. The pellets, after washing in sterile distilled water and then in 1 M sorbitol, were resuspended and incubated in 20 ml of SCE buffer (1 M sorbitol, 0.1 M sodium citrate, and 10 mM EDTA, pH 6.8) containing 20,000 U of lyticase and 0.2 mM β-mercaptoethanol in the dark at 30°C for 3 h with gentle agitation. The enzyme-S. cerevisiae mixture was checked microscopically to determine when the enzyme digestion was sufficient to produce S. cerevisiae protoplasts.

S. cerevisiae protoplast suspension was pelleted by centrifugation at 2,800 rpm for 15 min. Protoplast pellets, after washing with STC (1 M sorbitol, 10 mM CaCl2, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) twice, were resuspended in S. cerevisiae medium containing 0.8 M sorbitol and 0.2 M glucose, and the density was adjusted to 5 × 107 cells/ml for virus infection. Infected and uninfected protoplast cultures were placed on a shaker with gentle agitation at 28°C in the dark. Fresh medium without sorbitol was added to the S. cerevisiae cultures once a day at the beginning of culture and then based on the experimental requirements.

Virus infection.

BPV-1 virus was prepared from bovine papillomas as described previously (15). Virus suspensions were dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min, and the dialyzed virus was then added to S. cerevisiae protoplasts in culture. For infection, 1 ml of S. cerevisiae protoplasts at 5 × 107 cells/ml was exposed to 1 μl of a suspension of purified BPV-1 virions at an optical density at 595 nm (OD595) of 0.12, an OD equivalent to that observed with bovine serum albumin (60 μg/ml). Thus, 5 × 107 S. cerevisiae cells were exposed to 60 ng of BPV-1 virions or 1.5 × 109 virion particles, given a size for BPV-1 virions of ∼2 × 107 Da, for an approximate multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 30:1.

Hirt DNA preparation.

BPV-1-exposed S. cerevisiae cultures were harvested for preparation of Hirt DNA as described (25). Digestion of S. cerevisiae cells with enzyme was the same as that for S. cerevisiae protoplast preparation. The digested S. cerevisiae cells were washed with 1 M sorbitol and lysed in 400 μl of lysate buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM EDTA, and 0.2% Triton X-100) at room temperature for 10 min. Then 100 μl of 5 M NaCl was added to the lysate, and the mixture was frozen at −20°C for 40 min. The frozen lysates were thawed at room temperature for 20 min. The resultant supernatants containing viral DNA were incubated with 100 μg of proteinase K at 37°C for 1 h. The DNA was extracted with Tris-buffered phenol twice and chloroform once and then ethanol precipitated. The DNA was digested with various restriction enzymes, electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel, then blotted onto nylon membranes, and hybridized with a 32P-labeled BPV-1 DNA probe.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis of Hirt DNA.

Hirt DNA was separated on a neutral/alkaline two-dimensional gel (19). Hirt DNA was partially digested with HindIII for 2 h and then electrophoresed on a first-dimension agarose gel (0.4%) in TAE buffer (40 mM Tris-acetate, 2 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) at 1.5 V/cm for 20 h. The DNA lanes were run on a second-dimension agarose gel (1.0% agarose in sterile distilled H2O) in alkaline electrophoresis buffer (40 mM NaOH, 2 mM EDTA) at 1.5 V/cm for 24 h and then blotted onto nylon membranes. The DNA blots were hybridized with a 32P-labeled BPV-1 DNA probe.

RESULTS

S. cerevisiae protoplasts are permissive for uptake of BPV-1 virions.

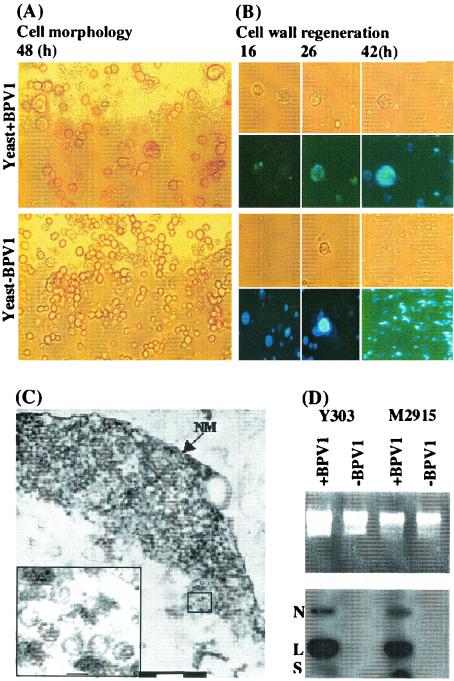

Protoplasts of S. cerevisiae were exposed to BPV-1 virions purified from bovine papillomas, and differences in the morphological appearance of S. cerevisiae protoplasts were observed several hours after exposure to virions that were not observed in unexposed protoplasts. In particular, many of the cells exposed to virions were observed to be larger than unexposed cells (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Morphological observations and Southern blot analysis of BPV-1-infected S. cerevisiae culture. (A) Morphology of S. cerevisiae protoplasts after 2 days in culture without and with BPV-1 virus exposure. (B) Cell wall regeneration of S. cerevisiae protoplasts with and without exposure to BPV-1 virions at various time points in culture as indicated, demonstrated in the lower panels by staining with Calcofluor. Upper panels in each case show light microscopy of the same field. (C) Transmission electron micrograph of a nuclear section of S. cerevisiae exposed to BPV-1 virus. NM indicates the nuclear membrane. Bars, 200 nm. The inset shows an enlargement of a selected part (small square) of the main picture, and bar represents 50 nm. (D) Southern blot analysis of two S. cerevisiae strains, exposed as shown to BPV-1 virus 48 h previously. S. cerevisiae (5 ml; 5 × 107cells/ml) was infected with 0.2 μg of BPV-1 virus and cultured with gentle shaking at 28°C in the dark. At 24 h, 5 ml of fresh medium was added. S. cerevisiae was collected for Hirt DNA preparation at 48 h, and 10 μg of DNA was used for Southern blot analysis. N, nicked circle; L, linear; S, supercoiled DNA.

Calcofluor White (4,4′-bis[4-anilino-6-bis[2-hydroxyethyl] amino-s-triazin-2-ylamino]-2,2′-stilbenedisulfonic acid) was used to examine cell wall regeneration of BPV-1-exposed and unexposed S. cerevisiae protoplasts in culture (Fig. 1B), and BPV-1-infected S. cerevisiae cells were much slower than uninfected S. cerevisiae cells to regenerate their cell wall. Based on the observed morphological changes, we looked for evidence of uptake of BPV-1 virus into the S. cerevisiae cells by thin-section electron microscopy and observed intact virions within S. cerevisiae cells (Fig. 1C). We also used immunofluorescence microscopy of BPV-1-infected S. cerevisiae cells to demonstrate BPV-1 L1 protein within S. cerevisiae nuclei, and over 40% of S. cerevisiae cells showed significant L1 staining 20 h postinfection following exposure of S. cerevisiae to virus at an MOI of 30:1.

To further confirm uptake of BPV-1 virions by S. cerevisiae protoplasts, we prepared Hirt supernatant DNA (Hirt DNA) from two S. cerevisiae lines (Y303 and M2915) before and after exposure to BPV-1 virions and examined the Hirt DNA for BPV-1 DNA by Southern blot. DNA hybridizing with BPV-1 DNA was detected in Hirt DNA prepared from both S. cerevisiae cell lines after exposure to BPV-1 virus, but not in the same cell lines prior to exposure (Fig. 1D). Moreover, no BPV-1 DNA was detected in Hirt DNA prepared from S. cerevisiae cell lines after exposure to an equivalent amount of viral DNA extracted from BPV-1 virions, suggesting that naked episomal HPV DNA is not taken up by S. cerevisiae cells.

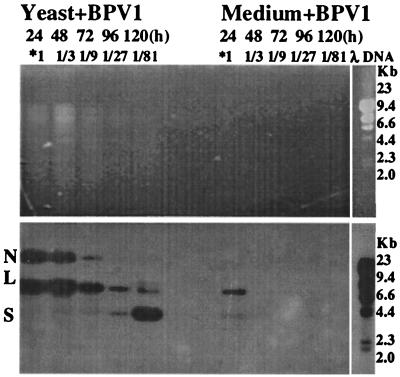

We then examined BPV-1 DNA in Hirt DNA samples prepared from one S. cerevisiae strain, Y303, exposed to a lesser quantity of BPV-1 virions at various time points after infection (Fig. 2). BPV-1-infected cultures were split every 24 h, and one third was used to prepare Hirt DNA, which was subjected to partial digestion with HindIII, which should cut BPV-1 DNA at a single site. Hirt DNA from BPV-1-infected S. cerevisiae cultures showed specific hybridization to bands corresponding to nicked circular, linear, and supercoiled monomeric BPV-1 DNA. The proportion of supercoiled BPV-1 DNA increased with time in culture, while the signals of the nicked circle and linear monomeric forms decreased over the same period (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

BPV-1 DNA detected by Southern blot in a BPV-infected S. cerevisiae culture over 5 days. S. cerevisiae (15 ml; 5 × 107cells/ml) was infected with 0.9 μg of BPV-1 virus. At 24 h, 10 ml of S. cerevisiae was collected, with 5 ml each being used for Hirt DNA and RNA preparation. Then 10 ml of fresh medium was added for continuing culture. Thereafter, 10 ml of S. cerevisiae was collected for Hirt DNA preparation and 10 ml of fresh medium was added every 24 h until 120 h. A total of 15 ml of medium was added to 0.9 μg of BPV-1 virus and similarly sampled and diluted. Hirt DNA prepared from 5 ml of S. cerevisiae cultures for each time point was resuspended in 200 μl of TE buffer. Then 20 μl of Hirt DNA, after digesting partially with HindIII for about 2 h, was electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel and blotted onto a nylon membrane. DNA blots were hybridized with whole BPV-1 DNA probe. As controls, 5 ml of medium infected with BPV-1 virus was pelleted for viral DNA extraction at high speed (10,000 rpm) for 30 min. The pellets were resuspended in 400 μl of lysate buffer and incubated with 100 μg of proteinase K at 37°C for 1 h. The DNA was extracted with Tris-buffered phenol and chloroform. The extracted DNA was also resuspended in 200 μl of TE buffer. Then 20 μl of the DNA suspensions was run on an agarose gel and blotted onto nylon membrane for BPV-1 DNA hybridization. The time point and effective culture dilution are shown above each lane. *1 indicates that the Hirt DNA contained the viral DNA from 0.03 μg of BPV-1 virions. The viral DNA dilution at the different time point is shown above each lane.

S. cerevisiae broth to which BPV-1 virions was added was similarly diluted every 24 h and used to prepare Hirt DNA, and the partially digested DNA prepared from the S. cerevisiae broth showed BPV-1-specific hybridization at 24 h, with no detectable signal by 120 h (Fig. 2). These results confirmed that intact BPV-1 virions were taken up by S. cerevisiae protoplasts and suggested that the BPV-1 genome could replicate in S. cerevisiae cells infected with natural virions.

BPV-1 DNA persists as an episome in BPV-1-infected S. cerevisiae.

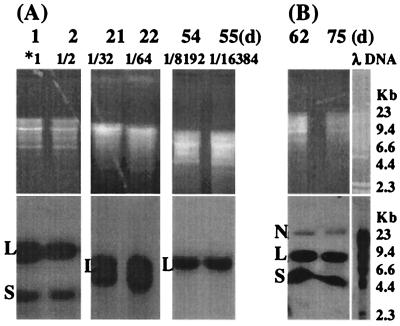

To determine whether the BPV-1 genome could persist and replicate at least as frequently as the S. cerevisiae genome in BPV-1-infected S. cerevisiae in long-term culture, we examined BPV-1 DNA in BPV-1-infected S. cerevisiae cultured over a prolonged period. S. cerevisiae was grown at 28°C for 5 days and subcultured daily and then held at 4°C for 15 days. A subculture was grown at 28°C and passaged daily for a further 5 days. From this subculture, another subculture was taken, held at 4°C for 25 days, and passaged daily at 28°C for a further 5 days. Samples taken at various time points were used to prepare Hirt DNA, which was tested for the BPV-1 genome as before (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

(A) BPV-1 DNA detected by Southern blot in a BPV-infected S. cerevisiae culture over 55 days. S. cerevisiae cells (10 ml; 5 × 107cells/ml) infected with 0.6 μg of BPV-1 was cultured at 28°C in the dark. At 1 day, 5 ml of S. cerevisiae cells was collected for Hirt DNA preparation, with 5 ml of fresh medium added for continuous culture. This was repeated every day until 5 days. At 5 days, 5 ml of S. cerevisiae cells was held at 4°C for 15 days. Then 5 ml of fresh medium was added, and cells were cultured at 28°C. From day 21 to day 25, 5 ml of S. cerevisiae culture was collected for Hirt DNA and 5 ml of fresh medium was added every day. A total of 5 ml of the 25-day S. cerevisiae culture was held at 4°C for 25 days. Fresh medium (5 ml) was added, and cells were cultured at 28°C, diluted, and sampled as previously from 51 days to 55 days. Hirt DNA (20 μl) was resuspended in 200 μl of TE buffer, partially (days 1, 2, 21, and 22) or completely (days 54 and 55) digested with HindIII, electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel, and blotted onto a nylon membrane. *1 indicates that the Hirt DNA contained the viral DNA from 0.03 μg of BPV-1 virus. Viral DNA dilution at the different time points is shown above each lane. The time point and effective culture dilution are shown above each lane. (B) BPV-1 DNA detected by Southern blot in a BPV-infected S. cerevisiae culture over 75 days. A total of 2 ml of S. cerevisiae cells (5 × 107cells/ml) infected with 0.06 μg of BPV-1 was cultured at 28°C in the dark. Then 2 ml of fresh medium was added once a week for continuous culture. Hirt DNA prepared from S. cerevisiae infected with BPV-1 virus 62 and 75 days postinfection was electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel without enzyme digestion. All blots were hybridized with BPV-1 DNA using [α-32P]dCTP at 3,000 Ci/mmol and exposed using Kodak BioMax film at −70°C for 24 h.

Incompletely HindIII-digested DNA hybridized with BPV-1, showing a linear form at 7.9 kb and a supercoiled band at 4.5 kb in all cultures tested (Fig. 3). After complete HindIII digestion, only a single band corresponding to linearized genome was seen. The persisting high-intensity BPV-1 hybridization signal over at least 13 population doublings, together with the persistence of a single DNA fragment of 7.9 kb after HindIII digestion, was strongly suggestive of efficient replication of BPV-1 episomal DNA in the S. cerevisiae cultures. In a separate long-term culture, we observed that S. cerevisiae infected with BPV-1 virions could maintain episomal BPV-1 DNA for over 75 days of continuous passage at 28°C (Fig. 3B).

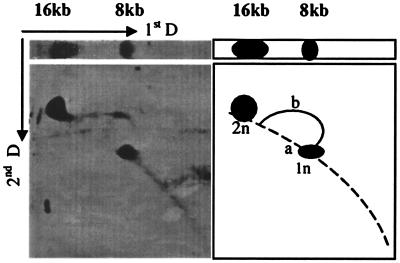

BPV-1 DNA is replicating in S. cerevisiae.

To confirm that DNA was replicating in S. cerevisiae, we analyzed the Hirt DNA prepared from BPV-1-infected S. cerevisiae cultures in neutral and alkaline two-dimensional gels. A typical replication pattern of BPV-1 DNA was observed, including 8-kb and 16-kb species and a single replication bubble (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis of Hirt DNA from BPV-1-infected S. cerevisiae cultures. A total of 10 μg of Hirt DNA was electrophoresed as described in the text, blotted onto nylon, and hybridized with a BPV-1 DNA probe. The left panel shows the hybridization results of the first- and second-dimensional blots, and the right panel shows the diagrammed pattern of the replication intermediates.

Episomal replication format of BPV-1 DNA in S. cerevisiae cultures.

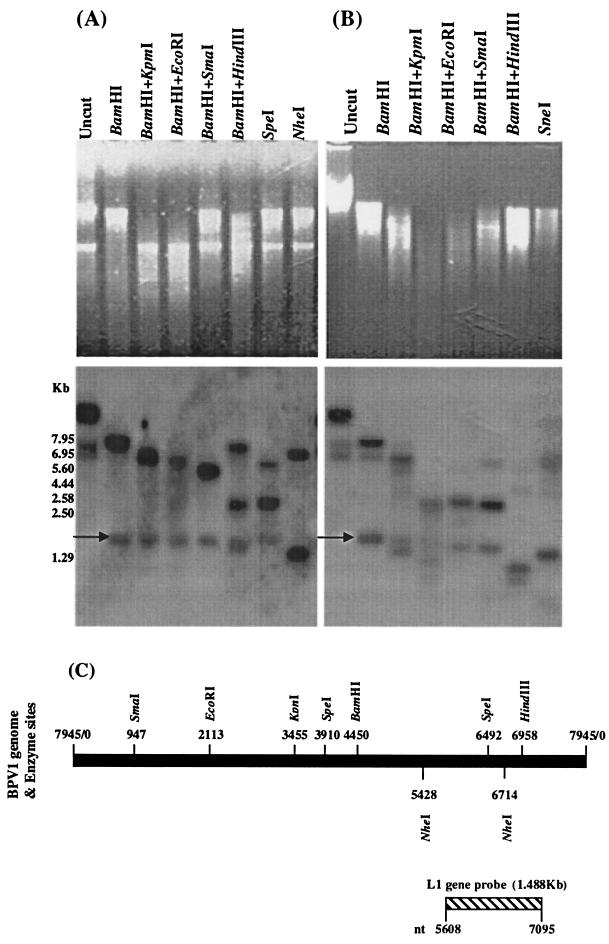

To characterize the amplified BPV-1 DNA, we used different combinations of enzymes to restrict the Hirt DNA samples prepared from BPV-1-infected S. cerevisiae cultures (Fig. 5). Uncut DNA from short-term and long-term cultures showed specific hybridization to three bands. The nicked circle form was much stronger than the other two forms in all three Hirt DNA samples. In Hirt DNA prepared from short-term BPV-1-infected S. cerevisiae culture (5 days), seven enzyme restriction treatments gave the expected fragments of BPV-1 DNA when the blot was probed using the BPV-1 L1 gene (Fig. 5A and C). In Hirt DNA prepared from long-term BPV-1-infected S. cerevisiae cultures (55 days), enzyme restrictions produced similar fragments hybridizing with BPV-1 DNA to those from short-term culture. A discrete band at 1.5 kb (arrow) of uncertain significance was also observed (Fig. 5A and B). These results confirm that BPV-1 DNA in short- and long-term S. cerevisiae cultures is maintained as a circular episome.

FIG. 5.

Restriction enzyme analysis of Hirt DNA prepared from BPV-1-infected S. cerevisiae cells in a 5-day culture (A) and a 55-day culture (B). A total of 10 μg of Hirt DNA, after overnight digestion with enzymes as shown, was electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel (upper panels), blotted onto nylon, and hybridized with the 32P-labeled BPV-1 L1 gene (lower panels). (C) Schema showing the restriction sites of seven enzymes for the BPV-1 genome and the location of the L1 probe.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we demonstrate that S. cerevisiae cells can take up BPV-1 virions and that the viral episome can replicate in the BPV-1-infected S. cerevisiae cells. This finding demonstrates two unexpected observations: uptake of papillomavirus by S. cerevisiae cells, and replication of the papillomavirus episome in S. cerevisiae.

Uptake of papillomaviruses into epithelial cells is assisted by receptors on the cell surface, including α6-integrin (5) and glycosaminoglycans (14). α6-Integrin is necessary for uptake of HPV-6 by some cells in vitro (16), while heparinlike glycosaminoglycans (syndecans) are essential for uptake in others (8). The proteoglycans of S. cerevisiae are not known to include syndecans. Saprophytic yeasts, however, expresses integrinlike molecules which allow the cells to adhere to cell surface structures (2), and S. cerevisiae also expresses an integrinlike protein on the cell membrane (12). Thus, there is a possible mechanism for papillomavirus binding and uptake by S. cerevisiae protoplasts, using an identified viral receptor protein.

We chose to conduct our experiments using S. cerevisiae protoplasts to maximize the possibility of demonstrating infection with BPV-1, as we wished to study the replication of papillomavirus within S. cerevisiae rather than the uptake process. Whether binding and uptake of papillomavirus could occur with intact S. cerevisiae is unknown, although the cell membrane of S. cerevisiae is available to the environment during fission.

Stable maintenance through replication of extrachromosomal DNA in S. cerevisiae requires autonomous replication sequences (ARS) (13, 23), and centromeric elements (CEN) (6, 7). There is a 10 of 11 nucleotide match to the consensus core ARS sequence (5′-[A/T]TTTAT[A/G]TTT[A/T]-3′) in the BPV-1 genome (accession no. J-02044) at nucleotides 7097 to 7087. Other AT-rich sequences can provide a similar function (27), and there are over 50 AT-rich 12-nucleotide sequences within the BPV-1 genome, which itself is relatively AT rich.

Both fission and budding yeasts can replicate plasmids containing the complete genome of BPV-1 together with ARS and CEN sequences (22), irrespective of whether they are introduced as a circular or linear structure. Furthermore, linearized BPV-1 genome, without ARS and CEN sequences but decorated with (T2G4)n “telomere” repeats, were maintained in the same study as an extrachromosomal structure in S. cerevisiae cells. Thus, our studies confirm this earlier observation that the BPV-1 genome can substitute for ARS and CEN in S. cerevisiae and demonstrate that circular episomal replication of the BPV-1 genome can occur in the absence of exogenous telomere repeats.

In keeping with our current observations, it has been observed that the full-length HPV16 genome when linked in cis to a selectable S. cerevisiae marker gene, either trp or ura, can replicate stably as an episome in S. cerevisiae (1). In our system, stability of the virus plasmid was also high in the absence of a selectable marker, with no loss of virus plasmids detected over 13 population doublings.

Papillomaviruses replicate in stratified squamous epithelial tissues in which the viral genome is found as a nuclear plasmid. The viral elements required for the initiation of replication of BPV-1 DNA include the origin region (20) and two trans-acting factors, the E1 and E2 proteins (21, 24). In the present study, we have not examined specific requirements for papillomavirus gene products in the replication of the papillomavirus genome, though we have observed expression of early- and late-gene mRNA species and protein in infected S. cerevisiae cells (unpublished data). Angeletti et al. (1) observed that the HPV-16 genome can replicate in S. cerevisiae without the capacity to transcribe any of its open reading frames. The E2 gene expressed in trans nevertheless increased the copy number of the HPV-16 genome. Further experiments are therefore required to establish the role of virus-encoded proteins acting in cis or in trans in the replication of the BPV-1 episome in S. cerevisiae.

In conclusion, our study, together with that by Angeletti et al. (1), offers further insights into the minimal requirements for replication of extrachromosomal DNA in S. cerevisiae and raises the possibility that S. cerevisiae might act as a permissive host for at least some part of the papillomavirus replicative cycle. Preliminary data (unpublished) suggest that BPV-1 proteins are effectively expressed in S. cerevisiae after BPV-1 infection, producing virions containing episomal BPV-1 DNA, and that the yield of virions is at least equivalent to the input virus.

Acknowledgments

This work was initiated in collaboration with the late Jian Zhou, who made seminal contributions to the design of the initial experimental work. We thank Xin Jie Chen and Wen Jun Liu for helpful discussions.

This work was funded in part by the Queensland Cancer Fund, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, and the Princess Alexandra Hospital Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angeletti, P. C., K. Kim, F. J. Fernandez, and P. F. Lambert. 2002. Stable replication of papillomavirus genomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Virol. 76:3350-3358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bendel, C. M., J. St Sauver, S. Carlson, and M. K. Hostetter. 1995. Epithelial adhesion in yeast species: correlation with surface expression of the integrin analog. J. Infect. Dis. 171:1660-1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng, S., D. C. Schmidt-Grimminger, T. Murant, T. R. Broker, and L. T. Chow. 1995. Differentiation-dependent up-regulation of the human papillomavirus E7 gene reactivates cellular DNA replication in suprabasal differentiated keratinocytes. Genes Dev. 9:2335-2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dollard, S. C., J. L. Wilson, L. M. Demeter, W. Bonnez, R. C. Reichman, T. R. Broker, and L. T. Chow. 1992. Production of human papillomavirus and modulation of the infectious program in epithelial raft cultures. Genes Dev. 6:1131-1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evander, M., I. H. Frazer, E. Payne, Y. M. Qi, K. Hengst, and N. A. McMillan. 1997. Identification of the α6 integrin as a candidate receptor for papillomaviruses. J. Virol. 71:2449-2456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fangman, W. L., R. H. Hice, and E. Chlebowicz-Sledziewska. 1983. ARS replication during the yeast S phase. Cell 32:831-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fitzgerald-Hayes, M., J. M. Buhler, T. G. Cooper, and J. Carbon. 1982. Isolation and subcloning analysis of functional centromere DNA (CEN11) from Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosome XI. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2:82-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giroglou, T., L. Florin, F. Schäfer, R. E. Streeck, and M. Sapp. 2001. Human papillomavirus infection requires cell surface heparan sulfate. J. Virol. 75:1565-1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grassmann, K., B. Rapp, H. Maschek, K. U. Petry, and T. Iftner. 1996. Identification of a differentiation-inducible promoter in the E7 open reading frame of human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV-16) in raft cultures of a new cell line containing high copy numbers of episomal HPV-16 DNA. J. Virol. 70:2339-2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins, G. D., D. M. Uzelin, G. E. Phillips, P. McEvoy, R. Marin, and C. J. Burrell. 1992. Transcription patterns of human papillomavirus type 16 in genital intraepithelial neoplasia: evidence for promoter usage within the E7 open reading frame during epithelial differentiation. J. Gen. Virol. 73:2047-2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hostetter, M. K. 1999. Integrin-like proteins in Candida spp. and other microorganisms. Fungal Genet. Biol. 28:135-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hostetter, M. K., N. J. Tao, C. Gale, D. J. Herman, M. McClellan, R. L. Sharp, and K. E. Kendrick. 1995. Antigenic and functional conservation of an integrin I-domain in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. Mol. Med. 55:122-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsiao, C. L., and J. Carbon. 1979. High-frequency transformation of yeast by plasmids containing the cloned yeast ARG4 gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:3829-3833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joyce, J. G., J. S. Tung, C. T. Przysiecki, J. C. Cook, E. D. Lehman, J. A. Sands, K. U. Jansens, and P. M. Keller. 1999. The L1 major capsid protein of human papillomavirus type 11 recombinant virus-like particles interacts with heparin and cell-surface glycosaminoglycans on human keratinocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 274:5810-5822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu, W. J., Y. M. Qi, K. N. Zhao, Y. H. Liu, X. S. Liu, and I. H. Frazer. 2001. Association of bovine papillomavirus type 1 with microtubules. Virology 282:237-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McMillan, N. A. J., E. Payne, I. H. Frazer, and M. Evander. 1999. Expression of the α6 integrin confers papillomavirus binding upon receptor-negative B-cells. Virology 261:271-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyers, C., and L. A. Laimins. 1994. In vitro systems for the study and propagation of human papillomaviruses. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 186:199-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitao, M., N. Nagai, R. U. Levine, S. J. Silverstein, and C. P. Crum. 1986. Human papillomavirus type 16 infection: a morphological spectrum with evidence for late gene expression. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 5:287-296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nawotka, K. A., and J. A. Huberman. 1988. Two-dimensional gel electrophoretic method for mapping DNA replicons. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:1408-1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pierrefite, V., and F. Cuzin. 1995. Replication efficiency of bovine papillomavirus type 1 DNA depends on cis-acting sequences distinct from the replication origin. J. Virol. 69:7682-7687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanders, C. M., and A. Stenlund. 2001. Mechanism and requirements for bovine papillomavirus, type 1, E1 initiator complex assembly promoted by the E2 transcription factor bound to distal sites. J. Biol. Chem. 276:23689-23699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shervington, A. A., J. A. Sparey, and C. J. Bostock. 1993. Behaviour of plasmid containing C4A2 repeats in S. cerevisiae and S. pombe. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int. 29:673-685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stinchcomb, D. T., K. Struhl, and R. W. Davis. 1979. Isolation and characterisation of a yeast chromosomal replicator. Nature 282:39-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ustav, M., and A. Stenlund. 1991. Transient replication of BPV-1 requires two viral polypeptides encoded by the E1 and E2 open reading frames. EMBO J. 10:449-457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao, K. N., X. Y. Sun, I. H. Frazer, and J. Zhou. 1998. DNA packaging by L1 and L2 capsid proteins of bovine papillomavirus type 1. Virology 243:482-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou, J., W. J. Liu, S. W. Peng, X. Y. Sun, and I. H. Frazer. 1999. Papillomavirus capsid protein expression level depends on the match between codon usage and tRNA availability. J. Virol. 73:4972-4982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zweifel, S. G., and W. L. Fangman. 1990. Creation of ARS activity in yeast through iteration of nonfunctional sequences. Yeast 6:179-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]