Abstract

Cellular and molecular pathways underlying ischemic neurotoxicity are multifaceted and complex. Although many potentially neuroprotective agents have been investigated, the simplicity of their protective mechanisms has often resulted in insufficient clinical utility. We describe a previously uncharacterized class of potent neuroprotective compounds, represented by PAN-811, that effectively block both ischemic and hypoxic neurotoxicity. PAN-811 disrupts neurotoxic pathways by at least two modes of action. It causes a reduction of intracellular-free calcium as well as free radical scavenging resulting in a significant decrease in necrotic and apoptotic cell death. In a rat model of ischemic stroke, administration of PAN-811 i.c.v. 1 h after middle cerebral artery occlusion resulted in a 59% reduction in the volume of infarction. Human trials of PAN-811 for an unrelated indication have established a favorable safety and pharmacodynamic profile within the dose range required for neuroprotection warranting its clinical trial as a neuroprotective drug.

Keywords: hypoglycemia/hypoxia, neuroprotection, PAN-811/Triapine, oxidative, calcium

Hypoxia and ischemia, the combination of hypoxia and hypoglycemia (H/H), are significant contributors to cell death and dysfunction typifying neurodegenerative diseases. One example is ischemic stroke in which the transport of oxygen and glucose is impaired by blockage of a cerebral artery causing neurological deficits (1). Pathologically, a stroke results in rapid cellular necrosis in the central core of the infarcted region and delayed neuronal cell death in the surrounding area (penumbra). Neurodegeneration may continue for several days despite tissue reperfusion. Serious ischemia and mild temporary ischemia (or hypoxia alone) seem to be responsible for the neuronal cell death in the central core and penumbra, respectively. By way of example, during 2-h middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAo) in the rat, the concentration of glucose is greatly reduced in the central core of the infarct, but only mildly in the penumbra. Restoration of glucose to a normal level occurs in both areas ≈1 h after reperfusion (2). Reperfusion also restores interstitial oxygen tension (pO2) in the central core to its preischemic value, but penumbral pO2 is recovered only partially (3). The effects of ischemia and hypoxia are primarily due to the initiation of a neurodegenerative signaling cascade involving release of glutamate and glutamate receptor activation, accumulation of free calcium ([Ca2+]i) intracellularly, free radical formation, and subsequent necrosis and apoptosis (4). The increase of [Ca2+]i plays a key role in cellular necrosis, which is reflected by a rapid and long-term decrease of extracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]e) in the central core. In contrast, the [Ca2+]e in the penumbra decreases only transiently (5). The quantity of free radicals increases significantly in the central core during both ischemia and reperfusion, whereas they increase in the penumbra only during reperfusion (6). Thus, it is clear that the intracellular mediators of the neurodegenerative cascade for ischemia-induced necrosis and hypoxia-induced apoptosis are, at least partially, different.

Inhibition of the neurodegenerative signaling cascade has been recognized as an important target for the treatment of both acute and delayed (chronic) neurodegenerative diseases. To date, drug development has generally focused on single-function agents such as antagonists of glutamate, Ca2+ channel blockers, scavengers of free radicals, and/or inhibitors of apoptosis. Unfortunately, many of these compounds either lack clinical efficacy or are hampered by dose-limiting adverse side effects (7-9). Therefore, there is much interest in the identification of new classes of compounds that may serve to inhibit the ischemic neuronal injury cascade, particularly those that can inhibit at multiple sites.

PAN-811, also known as 3-aminopyridine-2-carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazone or Triapine, is a small (molecular mass 195 Da) lipophilic compound belonging to the (N)-heterocyclic carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazone (HCT) class of molecules developed for the treatment of cancer (10). PAN-811 itself is currently under investigation in several phase II clinical trials for cancer therapy (11). HCTs are efficient chelators of metal ions and are known as potent ribonucleotide reductase inhibitors that function via quenching a tyrosyl free radical required for enzymatic function (12). We hypothesized that HCTs might protect neurons from the hypoxia- and/or ischemia-induced accumulation of [Ca2+]i by serving as metal chelators as well as the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) via free radical scavenging, both of which play major roles in the neurodegenerative cascade.

Results

PAN-811 Blocks both Ischemic and Hypoxic Neurotoxicity. Cocultured striatal and cortical neurons were used for this study because ischemic neuronal damage predominantly occurs in striatal and cortical regions of the cerebrum. Initial determination of the neuroprotective capacity of PAN-811 was accomplished via pretreatment of neurons 24 h before H/H or hypoxia at a dose of 2 μM. This concentration was maintained during the period of the stress and, in the case of hypoxia, during the subsequent recovery period as well. Efficacy was compared to that of several known neuroprotectants, including the high- and low-affinity NMDA receptor antagonists, MK-801 and memantine, and an extract of green tea (GT), which is known to contain several antioxidant compounds (13). As previously demonstrated, 5-10 μM MK-801 and memantine were chosen to protect excitatory neurotoxicity (14, 15). GT extract was used at a final dilution of 1:200 in the culture medium based on a dose-response test against H2O2 stress (unpublished data). Neuroprotection was quantified via the 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) assay, which measures mitochondrial function directly and indirectly reflects cell viability (Fig. 1). Five micomolar MK-801 suppressed H/H-induced neurotoxicity by 83%, whereas an equivalent dose of memantine and GT had little effect. In contrast, MK-801 at 5 μM only slightly affected hypoxia-induced neuronal cell death, whereas memantine achieved 50% protection. GT at a dilution of 1:200 fully rescued hypoxic neurotoxicity. These variations in the effects of these compounds indicate that different signaling mechanisms underlie neurodegeneration induced by H/H and hypoxia (delayed) and that each of the above compounds exerts its function via a distinct signaling mechanism. Interestingly, PAN-811 at dose 2.5-fold lower than the NMDA receptor antagonists completely blocked both H/H- and hypoxia-induced neurotoxicities. Under normoxic conditions, neurons morphologically display phase-brilliant cell soma and extend branched neurites. Incubation under conditions of H/H results in collapse of the neuronal cell body and shriveling of the neurites. Neurons treated with 2 μM PAN-811 remained healthy in both of these respects (Fig. 7a, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Hypoxia also caused shrinkage of cells and neuritic disruption, which also was inhibited by treatment with PAN-811 (Fig. 7b).

Fig. 1.

PAN-811 protects neurons from both ischemic and hypoxic stress. (a) Neurons were subjected to H/H for 6 h and allowed to recover for 24 h. Drug treatment, as indicated, was initiated 24 h before the stress and maintained during the period of ischemia. (b) Neurons were subjected to hypoxia for 18 h and allowed to recover for 24 h. Drug treatment, as indicated, was initiated 24 h before stressing and maintained during the periods of hypoxia and recovery. Cell viability/mitochondrial function was determined via the MTS assay. The gray and black bars indicate treatment under normoxic (control) and stressed conditions, respectively. MTS data are expressed as % protection = (compound treated - stressed)/(normoxia - stressed) × 100%. Figure symbols are ##, P < 0.01 compared with control; **, P < 0.01 compared with stressed. Veh, 1:12,500 PEG:EtOH; PAN, 2 μM PAN-811; GT, 1:200 GT; MK, 5 μM MK-801; Mem, 5 μM memantine.

Neuroprotective Efficacy, Therapeutic Window, and Toxic Dose of PAN-811. We next examined the effective dose range of PAN-811. As above, treatment of neurons with PAN-811 was initiated 24 h before H/H or hypoxic assault. Neuroprotection was evaluated via both MTS and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assays. The latter procedure measures leakage from cell membranes and is an indirect indication of neuronal cell death. PAN-811 at doses of 0.45 μM and 0.63 μM (EC50: 0.35 μM), efficiently blocked H/H-induced LDH release and mitochondrial dysfunction (Fig. 2 a and c). In contrast, PAN-811 at doses of 1.2 μM and 1.5 μM (EC50: 0.75 μM) inhibited hypoxia-induced LDH release and mitochondrial dysfunction (Fig. 2 b and d). PAN-811 was also examined at doses between 2 to 50 μM under normoxic, H/H, and hypoxic conditions to evaluate potential toxicity (Fig. 2 e and f). At doses up to 50 μM, PAN-811 did not elicit any neurotoxicity and efficiently protected against an H/H stress (30 h of total exposure). However, in longer experiments that included a 66-h exposure to the drug, PAN-811 at a dose of 50 μM resulted in neuronal cell death (Fig. 2f).

Fig. 2.

Determination of the efficacy, toxicity, and treatment window for PAN-811 neuroprotection. (a and b) Efficacy of PAN-811 vis-à-vis prevention of mitochondrial dysfunction induced by H/H and hypoxia, respectively. (c and d) Efficacy of PAN-811 in suppressing H/H- and hypoxia-induced cell membrane leakage, respectively. (e and f) Neurons treated with a broad dose range of PAN-811 were quantitatively examined with the MTS assay after H/H and hypoxia, respectively. (g) Effect of administration of PAN-811 at various treatment windows on H/H-induced cell membrane leakage (Before, 24-h pretreatment before H/H; During, the 6-h period during H/H; After, for a 48-h period after H/H). (h) Posttreatment window. Two micromolar PAN-811 or 1:12,500 PEG:EtOH was administered at varying times after termination of H/H. Mitochondrial function was measured with MTS assay 24 h after termination of H/H. MTS data in a, b, e, f, and h is expressed as % protection = (treated - stressed)/(normoxia - stressed) × 100%. LDH data in (c, d, and g) are expressed as % protection = (stressed - treated)/(stressed - normoxia) × 100%. Open (or gray) and filled bars indicate vehicle (control) and stressed groups, respectively. Figure symbols are ##, P < 0.01 compared with control; **, P < 0.01 compared with stressed.

We also explored the therapeutic window for administration of PAN-811 as a neuroprotectant. In contrast to the above regime, here we compared the efficacy of treatment against H/H stress when the drug was present only during the 24-h pretreatment period, for the 6 h during the H/H insult, or for a 48-hour recovery period subsequent to H/H. Results were quantified with the LDH assay (Fig. 2g), and cells were also evaluated morphologically (Fig. 7c). Pretreatment with PAN-811 showed minimal protection, whereas neurons that received PAN-811 during or especially after H/H stress were well protected. Complete protection was obtained even when PAN-811 was administered 6 h after the termination of H/H (Fig. 2h).

PAN-811 Blocks both Necrosis and Apoptosis. To understand the neuroprotective mechanism of PAN-811, we examined the process of neuronal cell death under both H/H and hypoxic conditions. Cellular necrosis and/or apoptosis of neurons were followed by staining with both Annexin V and 6-carboxyfluorescein diacetate. H/H predominately elicited necrosis, whereas hypoxia mainly induced apoptotic cell death (Fig. 8a, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 (10 μM) protected neurons from the H/H-induced necrosis but was ineffective in inhibiting hypoxia-induced neuronal apoptosis. In contrast, PAN-811 at the same dose was able to block both hypoxia- and H/H-induced apoptotic and necrotic cell death. DNA fragmentation analysis for H/H-stressed neurons supported the above results, showing predominately a smear pattern, an indication of necrosis, with only a weak DNA ladder, a sign of apoptosis (Fig. 8b). PAN-811 prevented the appearance of both the DNA smear and ladder. Because apoptosis dominates hypoxic cell death and is also involved in H/H-induced cell death, we examined the expressions of several apoptosis-related proteins, including Bax (proapoptotic), Bcl-2, and Bcl-XL (antiapoptotic) by using Western blot analysis (Fig. 3 a and b; refs. 16 and 17). Both hypoxia and H/H down-regulated Bcl-XL expression and H/H resulted in Bcl-2 reduction with a slight elevation of Bax expression. After H/H stress, both PAN-811 and MK-801 preserved the Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL levels significantly but failed to suppress the Bax signal. PAN-811 also inhibited hypoxia-induced down-regulation of Bcl-XL. Thus, PAN-811 functions, in part, by blocking the down-regulation of antiapoptotic proteins.

Fig. 3.

Effects of PAN-811 on the expressions of proapoptotic and antiapoptotic proteins. (a and b) Measurement of pro- and antiapoptotic proteins by Western blotting after H/H and hypoxic stresses, respectively. Band densities in the Western blots were analyzed with imagej (National Institutes of Health) and normalized against α-tubulin. Veh, 1:5,000 PEG:EtOH; PAN, 5 μM PAN-811; MK, 5 μM MK-801, Norm, normoxia, Hypo, hypoxia.

PAN-811 Chelates [Ca2+]i. [Ca2+]i plays an important role in mediating H/H-induced, necrosis-dominated cell death as is evident from the efficient block of ischemic cell death by the high-affinity NMDA receptor antagonist, MK-801. We used the fluorescent dye, Fura Red, to measure [Ca2+]i levels in hypoxia- or H/H-stressed neurons (Fig. 4). In a cell-free system, the fluorescence intensity of Fura Red gradually decreases after the binding of free Ca2+ (Fig. 9a, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). This binding can be monitored by evaluating an increase in the ratio of emitted light at 620 nm after excitation at 450 nm and 492 nm, respectively (Fig. 4a) Hypoxic stress induced only a marginal, statistically insignificant reduction in the Fura Red signal (Figs. 4c and 9b), which does not correlate to the 3.8-fold increase in LDH release (Fig. 4d), indicating that hypoxic cell death is less related to intracellular Ca2+ accumulation than that of ROS (vide in fra). Consistent with this finding, MK-801 only marginally reversed hypoxic neurodegeneration (Fig. 4d). PAN-811, however, completely blocked the hypoxic cell death presumably due to a non-Ca2+-related mechanism. Intracellular Ca2+ levels increased 19-fold because of H/H stress. PAN-811 at a dose of 5 μM reduced this elevated level by 72%. MK-801 at the same dose showed a similar protection, decreasing the H/H-induced [Ca2+]i by 80% (Figs. 4e and 9c). Accordingly, both PAN-811 and MK-801 completely blocked cell membrane leakage in the H/H condition (Fig. 4f). MK-801 elicits its effects on [Ca2+]i via antagonism of the NMDA receptor. PAN-811 would be expected to reduce free Ca2+ by ion chelation. To investigate whether PAN-811, in fact, can chelate free calcium in a similar fashion as it does with iron, we examined the capability of PAN-811 to directly bind to Ca2+ in a cell-free system, taking EDTA as a positive control (Fig. 4b). PAN-811 decreased Fura Red-available Ca2+ as efficiently as EDTA indicating its ability to chelate-free Ca2+.

Fig. 4.

Neuroprotection by PAN-811 occurs via chelation of [Ca2+]i in H/H. (a) Fura Red dye is responsive to changes in free Ca2+ concentration. Different concentrations of CaCl2 were coincubated with 15.3 μM Fura Red at 37°C for 30 min and measured at Ex450/Em620 and Ex492/Em620 nm, respectively. The Ca2+-bound dye was determined by taking the ratio of emitted fluorescence after excitation at 450/492 nm, which increased after the binding of Ca2+. (b) Chelation of Ca2+ by PAN-811 is shown by the dose-dependent reduction in intensity of Ca2+-bound Fura Red when incubated at various concentrations of PAN-811 with 1 μM CaCl2 in a cell-free system for 30 min at 37°C. EDTA was taken as a positive control. (c and e) The [Ca2+]i levels in hypoxic and H/H stressed neurons were quantified by determination of the ratio of emitted fluorescence at 620 nm after excitation at 450/492 nm after Fura Red staining. (d and f) LDH assay for hypoxia and H/H treated neurons, respectively. In b-f, the gray and black bars indicate treatment under normoxic (control) and stressed conditions, respectively. Figure symbols are ##, P < 0.01 compared with control; **, P < 0.01 compared with stressed. Veh, 1:5,000 PEG:EtOH; PAN, 5 μM PAN-811; MK, 5 μM MK-801.

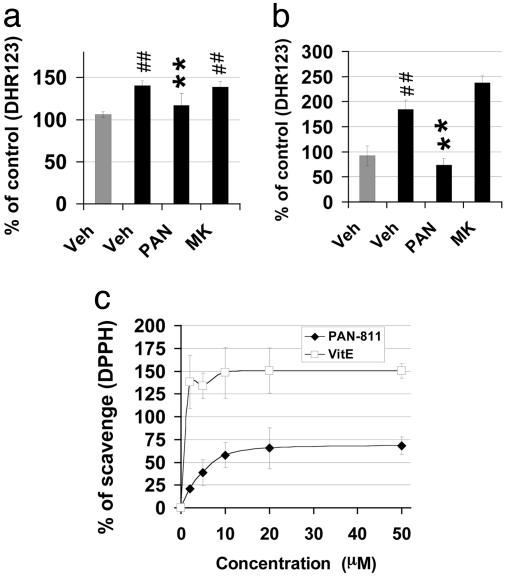

PAN-811 Significantly Reduces Cellular ROS and Acts as a Free Radical Scavenger. ROS may be the dominant cause of hypoxic cell death as indicated by the efficient neuroprotection of GT (containing antioxidants) but not MK-801. As indicated above, increases in [Ca2+]i are less relevant to hypoxic cell death. We further examined the intracellular level of ROS with the dye dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR123). Hypoxia causes a 1.4-fold enhancement in the intensity of DHR123 fluorescence (Figs. 5a and 9d). PAN-811 reduces the increased level of ROS to normal and blocks neuronal cell death, whereas MK-801 displays only a marginal effect (Fig. 4d). H/H induced a 1.8-fold enhancement in DHR123 intensity (Fig. 5b and 9e). MK-801 efficiently blocks H/H-induced neuronal cell death (Fig. 4f) but does not display a significant effect in reducing the fluorescence intensity of DHR123 (Fig. 5b and 9e). In contrast, PAN-811 fully suppressed the DHR123 signal to the normal level and efficiently blocked H/H-induced neuronal cell death (Figs. 4f and 5b). The lack of suppression of ROS levels by MK-801 in the case of H/H-induced neurotoxicity despite its ability to block the increase in [Ca2+]i suggests that the signals of ROS and [Ca2+]i are not tightly coupled and that PAN-811 reduces ROS accumulation via a mechanism distinct from Ca2+ chelation. We therefore investigated whether PAN-811 could act as a free radical scavenger. PAN-811 was coincubated with a stable free radical diphenylpicrylhydrazyl (DPPH) in a cell-free and metal-free system by using vitamin E, a known free radical scavenger, as a positive control (Fig. 5c). PAN-811 scavenged DPPH in a dose-dependent manner, maximally scavenging ≈70% of 500 μM DPPH. In contrast, MK-801 did not display a significant scavenging effect (data not shown). Thus, PAN-811 can function as a free radical scavenger.

Fig. 5.

Neuroprotection by PAN-811 occurs via free radical scavenging. (a and b) Quantification of DHR123 fluorescence for hypoxia and H/H stressed neurons, respectively. PAN-811, but not MK-801, at a dose of 5 μM inhibited ROS accumulation in hypoxia- or H/H-stressed neurons. (c) Direct free radical scavenging function of PAN-811. % of scavenging = (DPPH - DPPH with compound)/(DPPH × 100%). Gray and black bars indicates treatment under normoxic (control) and stressed conditions, respectively. Figure symbols are ##, P < 0.01 compared with control; **, P < 0.01 compared with stressed. Veh, 1:5000 PEG:EtOH; PAN, 5 μM PAN-811; MK, 5 μM MK-801.

PAN-811 Significantly Reduces Infarct Volume in an Animal Model of Stroke. The superior neuroprotective effect and multifunctional mechanism of action of PAN-811 prompted us to extend our research to an in vivo study. To understand the direct effect of this compound on the ischemic brain of the rat subjected to MCAo, PAN-811 was administered i.c.v. at a dose of 50 μg per rat 1 h after arterial occlusion. Staining of consecutive brain sections demonstrated that PAN-811 greatly reduced the size of the infarct (Fig. 6a). Computer-assisted quantitative analysis revealed a 59% (P = 0.004) reduction in total infarct volume for PAN-811-treated rats (Fig. 6b). Thus, PAN-811 can reduce ischemic neurodegeneration in vivo.

Fig. 6.

PAN-811 significantly reduces infarct volume in an animal model of stroke. PAN-811 was administered i.c.v. (50 μg per rat) 1 h after initiation of ischemia (1 h before reperfusion). (a) Rats were killed 22 h after reperfusion and consecutive coronal sections (2 mm thick) were stained with 2,3,5-triphyltetrazolium chloride. Unstained areas indicate the infarcted tissue (see arrow). (b) Infarct volumes were quantified by computer-assisted image analysis and evaluated statistically at a significance level of 5% with the Student t test (**, P < 0.005).

Discussion

The cell death that is seen in both acute and chronic neurodegenerative diseases is complex, and depending on its physical location, a neuron may be exposed to varying levels of both ischemia and hypoxia (2, 3, 5, 6). NMDA receptor antagonists, such as MK-801, primarily protect against ischemic cell death, whereas antioxidants, such as those found in extracts of GT, block only hypoxic cell death. These results indicate that neuronal cell death is controlled by several different signaling pathways (18). Intracellular Ca2+ is a key mediator of H/H-induced cell death predominantly via necrosis (19). Although ROS levels increase significantly under ischemic stress, its effects are evidently secondary to [Ca2+]i accumulation, as a reduction of [Ca2+]i alone is sufficient to reduce H/H-induced neurodegeneration. In comparison, [Ca2+]i is only marginally increased in hypoxia-stressed neurons, and ROS plays the key role as intracellular mediator for hypoxia-induced cell death, predominantly via apoptosis (3, 20). Our findings demonstrate that PAN-811 is a potent neuroprotectant that fully blocks both H/H- and hypoxia-induced neurotoxicities in vitro, indicating its dual effects on the neurotoxic pathways. This mechanism is further evidenced by the ability of PAN-811 to reduce free calcium by direct ion chelation and to decrease ROS via free radical scavenging. Down-regulation of Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL after H/H or hypoxic insult is likely via a Ca2+-dependent mechanism, because MK-801 also maintains the levels of these proteins.

The effective dose of PAN-811 (≈1 μM) is well below its maximal tolerated dose (50 μM), which bodes well for its potential clinical use. It is important to note that PAN-811 has already been investigated clinically for the treatment of cancer, where much higher doses are used (10, 21). The use of PAN-811 in the treatment of cancer to block cellular proliferation is in stark contrast to its function in neuroprotection, where it promotes cellular survival. This discrepancy must be viewed in light of two important points: the difference in the efficacious and toxic doses and the difference in the state of differentiation of neoplastic cells versus mature neurons. PAN-811 is an inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase, which is essential for actively proliferating tumor cells but likely not vital for terminally differentiated neurons.

Administration of PAN-811 i.c.v. into the brain of rats subjected to MCAo at 1 h after occlusion reduced the infarct volume by an average of 59%. It is especially important to note that PAN-811 was effective when administered well after the initiation of arterial occlusion. This finding is consonant with experiments in vitro indicating greater efficacy when administered during and/or after ischemic stress.

PAN-811 is a previously uncharacterized neuroprotective compound distinguished by its dual mode of action; direct chelation of Ca2+ and free radical scavenging. Other neuroprotectants generally display only a single function. Those that control Ca2+ influx, either via receptor antagonism or channel blocking, commonly effect only one pathway for Ca2+ influx but allow accumulation of [Ca2+]i by another type of receptor or channel (22-24). In contrast, PAN-811 chelates [Ca2+]i down-stream of the receptor or channel regardless of its mode of influx. Although inhibitors of ROS and free radical scavengers have been investigated, they generally lack efficacy in clinical trials (7-9, 25) likely due to the lesser role of ROS in H/H-induced neuronal cell death. On the other hand, hypoxia is likely to play an important role in neuronal death, especially at the periphery of the infarct. The in vivo neuroprotective efficacy of PAN-811 is now clearly established, and its ability to be used subsequent to arterial occlusion distinguishes it from many other neuroprotectants such as antioxidants, ginkgo biloba extract, and α-lipoic acid (26). It is also superior to the manganese superoxide dismutase mimetic M40401, which is reported to reduce MCAo-induced infarct volume by 73% when animals are pretreated but fails to reduce lesion volume significantly when administered subsequent to MCAo (27). The superior efficacy of PAN-811 in blocking both acute and delayed neurodegeneration, its low neural toxicity, dual functions of calcium chelation and free radical scavenging, potent neuroprotection in vivo, known human safety profile (10, 11, 21), and favorable therapeutic window suggest a significant potential for PAN-811 as a neuroprotective agent for use in stroke and certain chronic neurodegenerative disorders.

Materials and Methods

Neuronal Culture and in Vitro Neurotoxicity Models. Neurons were isolated from the cortex and striatum of embryonic day 17 male Sprague-Dawley rats and seeded at 5 × 104 cells per well in 96-well plates. To obtain highly enriched neurons (≈95%), neurons were cultured in Neurobasal medium containing B27 supplement without AO (Invitrogen) for 2 weeks before H/H and 3 weeks for stressing with hypoxia only (14).

H/H was produced in vitro by reducing the concentration of glucose to 1.2 mM by diluting the culture medium with degassed balanced salt solution (BSS) (28) and O2 to 0% in a sealed container filled with 5% CO2 and 95% N2. Control specimens were treated with nondegassed BSS containing 25 mM glucose and ambient air with 5% CO2. After 6 h, the solutions in both hypoxic and normoxic cultures were diluted with a termination solution (28) and further cultured in 5% CO2 and 95% ambient air for another 24 or 48 h. In the hypoxia-only study, the plates were incubated in 95% N2 and 5% CO2 at 37°C for 18 h in normal culture medium. Control (normoxic) plates were incubated in ambient air with 5% CO2 for the same time period. Neurons were treated with the PAN-811 solvent, 7:3 polyethylene glycol: ethanol (PEG:EtOH), PAN-811 in PEG:EtOH, extract of GT (GT prepared by mixing 200 mg of tea with 1 ml of deionized water, boiling for 10 min, centrifuging at 100 × g for 10 min to sediment particulate matter, and harvesting the supernatant solution), Memantine, or MK-801.

MTS and LDH Assays and Morphological Monitoring. Ten microliters of MTS reagent (Promega) was added to a covered culture well containing neurons in 50 μl of medium. The preparations were incubated at 37°C for 1 h, and absorbance was recorded at 490 nm by using a 96-well plate reader (Model 550, Bio-Rad). For the LDH assay, a mixture of a 35-μl aliquot of culture medium and 17.5 μl of substrate, enzyme, and dye solutions (Sigma) was incubated at room temperature for 30 min, and absorbance was measured at 490 nm by using a plate reader. Neuronal cell death was determined morphologically based on the integrity of the cell soma and continuity of neuronal processes and photographed under an inverted phase-contrast microscope (IX 70, Olympus).

Determination of Necrosis and Apoptosis with AnnCy3/6-Carboxy-fluorescein Diacetate and DNA Fragmentation. Apoptosis Detection Kit (catalog no. APO-AC1) was purchased from Sigma, and the assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Photography was carried out at ×300 magnification under an inverted microscope (IX 70, Olympus) equipped with fluorescent light source (BH2-RFL-T3) and a digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI). DNA was extracted with the DNeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). DNA samples were loaded onto a 1.2% agarose gel, and electrophoresed in 1× Tris-Acetate-EDTA buffer at room temperature at 110V for 1.5 h and compared to a 5-kb DNA ladder.

Calcium Determination. Fluorescence intensity of Fura Red was photographed under the fluorescent microscope. Ca2+-bound and unbound Fura Red was measured at excitation wavelength of 450 nm and 492 nm, respectively, and an emission of 620 nm with a fluorescent microplate reader (POLARStar, BMG LABTECH, Offenburg, Germany). The ratio of the readings at 450/492 was calculated and normalized against the MTS value of each well.

ROS Examination. Neurons were incubated in 15 μM DHR123 (Molecular Probes) for 30 min at 37°C to determine intramitochondrial ROS levels. Fluorescence was photographed by using a fluorescent microscope and quantified by excitation at 492 nm and emission at 590 nm. DPPH was determined by incubating varying amounts of PAN-811 with 500 μM DPPH for 90 min at room temperature. Vitamin E was taken as positive control. Optical density was measured at 520 nm by using a 96-well plate reader.

Western Blotting. After normalization and denaturation, proteins were separated in 4-15% Tris·HCl gel (Bio-Rad) at 170 V for 50 min, and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Pierce) at 0.17 A at room temperature for 1 h. After a blocking step, the membrane was treated with 1:100 or 1:200 primary antibody in 2% milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST) at room temperature for 1 h, washed and treated with 1:5,000 anti-mouse IgG in TBST at room temperature for 1 h.

Mouse mAbs against α-Tubulin (sc-8035), Bax (sc-7480), Bcl-XL (H-5) (sc-8392), and Bcl-2 (sc-7382) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and anti-mouse IgG (31432) from Pierce.

Evaluation in MCAo Model. The procedure was performed as described in ref. 29. Temporary (2-h) cerebral ischemia was induced by occluding the middle cerebral artery of anesthetized male Sprague-Dawley rats (270-330 g) with a 3-0 nylon suture. PAN-811 at a dose of 50 μg per rat was delivered i.c.v. 1 h after MCAo (n = 10). Control rats (n = 11) received vehicle only. At 22 h after reperfusion, rats were deeply anesthetized and killed by decapitation, and their brains were removed for quantification of the volume of infarction by staining 2-mm thick coronal sections with 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (29) by using a computer-assisted image analysis system (Inquiry Digital Analysis System; Loats Associates, Westminster, MD).

Data Analysis. The data were generated from 4-6 replicate wells, expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and statistically evaluated at a significance level of 1% with one- or two-factor ANOVA by using software vassarstats (http://faculty.vassar.edu/lowry/VassarStats.html) followed by the Tukey HSD test. Figure symbols are as follows: ##, P < 0.01 compared with control; **, P < 0.01 compared with the stressed group. In vivo data were statistically evaluated at a significance level of 5% with Student's t test and expressed as mean ± SEM. Figure symbol ** is P < 0.005.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Claudia Gerwin at National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke for supplying us with embryonic rat brain tissue and Vion Pharmaceuticals (New Haven, CT) for PAN-811. Z.-G.J. was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant 1 R43 NS048694-01.

Author contributions: Z.-G.J. designed research; Z.-G.J., X.-C.M.L., V.N., and X.Y. performed research; W.P. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; Z.-G.J., R.-w.C., M.S.L., B.A., F.C.T., R.O.B., and H.A.G. analyzed data; and Z.-G.J., M.S.L., and R.O.B. wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest statement: Z.-G.J., V.N., M.S.L., and H.A.G. are employees of and H.A.G. owns stock in Panacea Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Abbreviations: DHR123, dihydrorhodamine 123; DPPH, diphenylpicrylhydrazyl; GT, green tea; H/H, hypoxia and hypoglycemia; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MCAo, middle cerebral artery occlusion; MTS, 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium; PEG:EtOH, polyethylene glycol:ethanol; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

References

- 1.Zerwic, J. J., Ennen, K. & DeVon, H. A. (2002) AAOHN J. 50, 354-359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Folbergrova, J., Zhao, Q., Katsura, K. & Siesjo, B. K. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 5057-5061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu, S., Shi, H., Liu, W., Furuichi, T., Timmins, G. S. & Liu, K. J. (2004) J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 24, 343-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacGregor, D. G., Avshalumov, M. V. & Rice, M. E. (2003) J. Neurochem. 85, 1402-1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kristian, T., Gido, G., Kuroda, S., Schutz, A. & Siesjo, B. K. (1998) Exp. Brain Res. 120, 503-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu, S., Liu, M., Peterson, S., Miyake, M., Vallyathan, V. & Liu, K. J. (2003) J. Neurosci. Res. 71, 882-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Legos, J. J., Tuma, R. F. & Barone, F. C. (2002) Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 11, 603-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandercock, P., Berge, E., Dennis, M., Forbes, J., Hand, P., Kwan, J., Lewis, S., Lindley, R., Neilson, A., Thomas, B. & Wardlaw, J. (2002) Health Technol. Assess. 6, 1-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sareen, D. (2002) J. Assoc. Physicians India 50, 250-258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giles, F. J., Fracasso, P. M., Kantarjian, H. M., Cortes, J. E., Brown, R. A., Verstovsek, S., Alvarado, Y., Thomas, D. A., Faderl, S., Garcia-Manero, G., et al. (2003) Leuk. Res. 27, 1077-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tam, T. F., Leung-Toung, R., Li, W., Wang, Y., Karimian, K. & Spino, M. (2003) Curr. Med. Chem. 10, 983-995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richardson, D. R. (2002) Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 42, 267-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kakuda, T. (2002) Biol. Pharm. Bull. 25, 1513-1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang, Z. G., Piggee, C., Heyes, M. P., Murphy, C., Quearry, B., Bauer, M., Zheng, J., Gendelman, H. E. & Markey, S. P. (2001) J. Neuroimmunol. 117, 97-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pringle, A.K., Self, J., Eshak, M. & Iannotti, F. (2000) Eur. J. Neurosci. 12, 3833-3842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitamura, Y., Shimohama, S., Kamoshima, W., Ota, T., Matsuoka, Y., Nomura, Y., Smith, M. A., Perry, G., Whitehouse, P. J. & Taniguchi, T. (1998) Brain Res. 780, 260-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raghupathi, R., Graham, D. I. & McIntosh, T. K. (2000) J. Neurotrauma 17, 927-938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hou, S. T. & MacManus, J. P. (2002) Int. Rev. Cytol. 221, 93-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Urushitani, M., Nakamizo, T., Inoue, R., Sawada, H., Kihara, T., Honda, K., Akaike, A. & Shimohama, S. (2001) J. Neurosci. Res. 63, 377-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beridze, M. Z., Urushadze, I. T. & Shakarishvili, R. R. (2001) Zh. Nevrol. Psikhiatr. Im. S.S. Korsakova Suppl. 3, 35-40. [PubMed]

- 21.Murren, J., Modiano, M., Clairmont, C., Lambert, P., Savaraj, N., Doyle, T. & Sznol, M. (2003) Clin. Cancer Res. 9, 4092-4100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller, R. J. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 1403-1406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mori, Y., Niidome, T., Fujita, Y., Mynlieff, M., Dirksen, R. T., Beam, K. G., Iwabe, N., Miyata, T., Furutama, D., Furuichi, T., et al. (1993). Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 707, 87-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsien, R. W., Ellinor, P. T. & Horne, W. A. (1991) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 12, 349-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wahlgren, N. G. & Ahmed, N. (2004) Cerebrovasc. Dis. 17, Suppl. 1, 153-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark, W. M., Rinker, L. G., Lessov, N. S., Lowery, S. L. & Cipolla, M. J. (2001) Stroke 32, 1000-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimizu, K., Rajapakse, N., Horiguchi, T., Payne, R. M. & Busija, D. W. (2003) Brain Res. 963, 8-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meloni, B. P., Majda, B. T. & Knuckey, N. W. (2001) Neuroscience 108, 17-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams, A. J., Dave, J. R., Phillips, J. B., Lin, Y., McCabe, R. T. & Tortella, F. C. (2000) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 294, 378-386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.