Abstract

Nur77 is a nuclear orphan receptor that is able to activate transcription independently of exogenous ligand, and has also been shown to promote apoptosis on its localization to mitochondria. Phosphorylation of Nur77 on Ser354 has been suggested to reduce ability of Nur77 to bind DNA; however, the kinase responsible for this phosphorylation in cells has not been clearly established. In the present study, we show that Nur77 is phosphorylated on this site by RSK (ribosomal S6 kinase) and MSK (mitogen- and stress-activated kinase), but not by PKB (protein kinase B) or PKA (protein kinase A), in vitro. In cells, phosphorylation of Nur77 in vivo is catalysed by RSK, which is activated downstream of the classical MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) cascade. Phosphorylation of Nur77 by RSK is able to promote the binding of Nur77 to 14-3-3 proteins in vitro, however, no evidence could be seen for this interaction in cells. We have established that two related proteins, Nurr1 and Nor1, are also phosphorylated on the equivalent site by RSK in cells in response to mitogenic stimulation.

Keywords: apoptosis, nuclear orphan receptor, Nur77, phosphorylation, protein kinase B (PKB), ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK)

Abbreviations: bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; CREB, cAMP-response-element-binding protein; DIG, digoxigenin; DMEM, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium; EGF, epidermal growth factor; ERK, extracellular-signal-regulated kinase; ES, embryonic stem; EST, expressed sequence tag; HA, haemagglutinin; HEK-293 cells, human embryonic kidney 293 cells; HRP, horseradish peroxidase; IGF, insulin-like growth factor; GSK3, glycogen synthase kinase-3; GST, glutathione S-transferase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MSK, mitogen- and stress-activated kinase; NGF, nerve growth factor; NBRE, NGF-induced B factor response element; NurRE, Nur response element; ORF, open reading frame; PDK1, phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PKA, protein kinase A; PKB, protein kinase B; RSK, ribosomal S6 kinase; RXR, retinoid X receptor

INTRODUCTION

Nuclear orphan receptors form part of the nuclear receptor family of transcription factors, which also includes retinoid, steroid and thyroid receptors. Nuclear orphan receptors are proteins for which no ligand is currently described, either because the ligand has not yet been identified or because they act in a ligand-independent manner [1]. The immediate early gene Nur77 (also referred to as NR4A1, NGFI-B or TR3) along with the related proteins Nurr1 (NR4A2) and Nor1 (NR4A3) make up one such group of nuclear orphan receptors referred to as the NR4A group. Nur77 is expressed in a variety of cell types, and has been implicated in both the regulation of genes in the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis associated with inflammation and steroidogenesis and also in the regulation of apoptosis. In T-cells, Nur77 is suggested to promote the apoptosis of immature self-reactive T-cells in the thymus [2–5], while, in other cell types, Nur77 has been reported to both promote or inhibit apoptosis [6–9].

Nur77, and also Nurr1 and Nor1, are able to bind as monomers to NBREs [NGF (nerve growth factor)-induced B factor response element) (AAAGGTCA) and as homodimers to NurREs (Nur response elements) (TGATATTTX6AAATGCCA) in DNA [10]. At present, no physiological ligand has been described for Nur77, although recently it has been suggested that 1,1-bis-(3′-indolyl)-1-(p-substituted phenyl) methanes may be able to activate Nur77 [11]. In most circumstances, Nur77 is thought to regulate transcription independently of ligand binding and, consistent with this, expression of Nur77 protein has been shown to be sufficient to activate transcription from Nur77-dependent reporter genes without the need for ligand stimulation [10,12]. The recent crystal structure of the ligand-binding domains of Nurr1 and Nur77 shows that these domains exist in a closed confirmation with the ligand-binding cleft inaccessible [13,14], consistent with a ligand-independent mechanism of action for these proteins. Given that regulation of NR4A transcriptional activity does not require ligand binding, it seems likely that NR4A regulation must occur via different mechanisms. Two possible ways this could occur are via the control of Nur77 protein levels in the cell, or by post-translational modifications of Nur77, such as phosphorylation, and evidence exists that both of these mechanisms may play a role. The Nur77, Nurr1 and Nor1 genes are immediate early genes, and can be up-regulated in cells via a variety of stimuli, including NGF, depolarization, serum, PMA, EGF (epidermal growth factor) and anisomycin [15–17]. Nur77 protein has also been shown to be a phospho-protein in cells, suggesting that its activity may be controlled by protein kinase signalling cascades, a mechanism common to other nuclear receptors as well as unrelated transcription factors such as FOXOs (forkhead box Os), CREB (cAMP-response-element-binding protein) and Ets factors [18–20].

Nur77 has been reported to be phosphorylated at several sites, including Ser142, Thr145 [21,22] and Ser354 (amino acid numbers are for murine Nur77). Ser354 lies in the A box of the DNA-binding domain of Nur77, a region of the protein adjacent to the zinc-finger domain. The phosphorylation of Ser354 is potentially important in Nur77 regulation, as phosphorylation of this site has been suggested to inhibit the DNA binding of Nur77 [23]. Consistent with this, the crystal structure of the Nur77 DNA-binding domain has shown that Ser354 forms a hydrogen bond to the phosphate backbone of the DNA [24]. Based on the crystal structure, the introduction of a negative charge by phosphorylation of this residue would be expected to interfere with the binding of the A box to DNA.

While there is evidence that phosphorylation of this site can have functional significance in cells, the pathways and kinases which control phosphorylation of this site are less well understood. In PC12 cells (derived from rat pheochromocytoma) stimulated with NGF or bFGF (basic fibroblast growth factor) Nur77 was reported to be phosphorylated on multiple sites. PMA or EGF stimulation was also reported to stimulate the phosphorylation of Nur77, but on fewer sites than NGF or bFGF [25], although the phosphorylated sites were not identified in these studies. Using phospho-specific antibodies against Ser354, NGF but not membrane depolarization [26] was found to promote phosphorylation of this site in PC12 cells. In NGF-stimulated PC12 cells, the kinase responsible for the phosphorylation of Ser354 of Nur77 was initially described as being distinct from RSK (ribosomal S6 kinase), but identical with the kinase responsible for the phosphorylation of CREB [23]. The kinases that phosphorylate CREB have since been identified as MSK1 (mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase 1) and MSK2 [27,28], which are known to be able to phosphorylate similar targets to RSK in vitro [29]. In contrast, other studies have reported that RSK is able to phosphorylate Nur77 in vitro [30,31], and also in cells [32]. These studies made use of biochemical purification and characterization of the Nur77 kinase in order to identify it; however, this can give rise to misleading results as partially purified kinases which phosphorylate a substrate in in vitro assays are not always the physiological kinases for the substrate. It is therefore necessary to also use other approaches to confirm that the correct kinase has been identified. More recently, PKB (protein kinase B)/Akt has been suggested as the kinase responsible for phosphorylation of Ser354 in Nur77. PKB has been shown to be able to phosphorylate the DNA-binding domain of Nur77 in vitro, and overexpression of PKB was found to stimulate the phosphorylation of Nur77 in both HEK-293 cells (human embryonic kidney 293 cells) and T-cells [2,33]. The phosphorylation of Nur77 in response to platelet-derived growth factor was reported to be inhibited by the PI3K (phosphoinositide 3-kinase) inhibitor wortmannin, which blocks the activation of PKB [33]. PKA (protein kinase A) has also been shown to phosphorylate the DNA-binding domain of Nur77 in vitro [26]. PKA, however, appears unlikely to phosphorylate Nur77 as agents that elevate cAMP in cells, and therefore activate PKA, have been shown in vivo to stimulate DNA binding of Nur77 and promote its dephosphorylation at Ser354 [34,35].

In the present paper, we have re-examined the phosphorylation of Nur77 on Ser354. Using a combination of cell-permeable kinase inhibitors and mouse knockin mutations, we show that Nur77 is phosphorylated by RSK in response to mitogenic stimulation of cells. We also find that RSK phosphorylates the equivalent site in both Nurr1 and Nor1. Phosphorylation of Nur77 on Ser354 did not, however, appear to affect the transcriptional activity of Nur77, or its ability to bind 14-3-3 proteins in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids

To produce GST (glutathione S-transferase)-tagged Nur77 expression vectors, the murine Nur77 ORF (open reading frame) was PCR amplified from IMAGE EST (expressed sequence tag) 3156434 with the primers gcggatccCCCTGTATTCAAGCTCAATATGGAACACC and gcggatccTCAGAAAGACAATGTGTCCATAAAGATCTTGTCC using the Expand HiFidelity PCR system (Roche). The PCR product was subcloned into pCR2.1 (Invitrogen) and sequenced. The resulting plasmid pCR2.1-Nur77 was digested with BamHI and subcloned into the same site in pGEX6P-1 or EBG2T, resulting in pGEX6P-1-Nur77 and EBG2T-Nur77. pCMV5-FLAG-Nur77 was produced in a similar fashion but the ORF was amplified using primers which added a FLAG epitope to the 5′-end of the fragment. This was subcloned into pCR2.1, sequenced and finally cloned into pCMV5 to produce pCMV5-FLAG-Nur77.

Nor1 was PCR amplified from IMAGE EST 30643330 using the primers gcggatccCCCTGCGTGCAAGCCCAGTATAG and gcggatccTCAGAAAGGCAGGGTGTCAAGGAAGA, which added BamHI restriction sites to both ends. The resulting fragment was cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen) and sequenced to completion. The EST was found to contain a F438S mutation which was corrected using the QuickChange Site Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The insert was then ligated into the BamHI site in EBG6P to produce EBG6P-Nor1. An N-terminal FLAG tag was added via PCR following the above procedure and ligated into the BamHI site of pCMV5 to produce pCMV5-FLAG-Nor1.

Murine Nurr1 was cloned from cDNA made from PMA-stimulated fibroblasts using the primers ATGCCTTGTGTTCAGGCGCAGTATGG and TTCTTTGACGTGCTTGGGAGAAGGTC. The PCR product was cloned into TOPO and sequenced. A FLAG tag was added by PCR and the insert was cloned into pCMV5 to generate pCMV5-FLAG-Nurr1.

DNA sequencing was carried out by the sequencing service (School of Life Sciences, University of Dundee, Scotland, U.K; www.dnaseq.co.uk) using Applied Biosystems Big-Dye Ver3.1 chemistry on a capillary sequencer.

Expression and purification of GST–Nur77 in Escherichia coli

GST–Nur77 was expressed in BL21 DE3 plysS E. coli from the plasmid pGEX6P-1-Nur77. Expression was induced by the addition of 100 mg/ml isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside, and the culture was then incubated for a further 4 h at 20 °C. Cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mm Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM PMSF and 1 mM benzamidine). Cells were then lysed by sonication and insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 20000 g for 15 min. GST–Nur77 was then bound to glutathione–Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences), then washed 4 times in lysis buffer, 4 times in 50 mm Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM PMSF and 1 mM benzamidine and once in 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5) and 0.27 M sucrose. GST–Nur77 was then eluted with 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 0.27 M sucrose and 20mM glutathione.

Phosphorylation reactions and phospho site mapping

One unit of activity (unit) was the amount which catalysed the phosphorylation of 1 nmol of peptide substrate (GRPRTSSFAEG for RSK, MSK1 and PKB or LRRASLG for PKA) in 1 min. Proteins were phosphorylated using 20 m-units of kinase in 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 0.1 mM EGTA, 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM magnesium acetate and 0.1 mM [32P]ATP at 30 °C for the times indicated. Reactions were stopped by the addition of SDS to a final concentration of 1% (w/v). Samples were run on a 4–12% (w/v) polyacrylamide gel, and the substrate band was excised and the amount of 32P incorporated was measured by Cerenkov counting. For phospho site mapping, the protein was reduced with dithiothreitol, alkylated with 4-vinylpyridine and digested with trypsin. The resulting peptides were applied to a Vydac 218TP5215 C18 column equilibrated in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and the column was developed with a linear gradient of acetonitrile/0.1% trifluoroacetic acid at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min while collecting 0.1 ml fractions. 32P radioactivity was recorded with an on-line monitor. Phosphorylation site mapping was performed essentially as described previously [36]. Identification of 32P-labelled peptides was performed by MALDI–TOF (matrix-assisted laser-desorption ionization–time-of-flight) MS on a PerSeptive Biosystems Elite STR using a matrix of 10 mg/ml α-cyanocinnamic acid in 50% (v/v) acetonitrile/0.1% trifluoroacetic acid/2 mM diammonium citrate. Analyses were also carried out by electrospray on a Waters QToF II. Sites of phosphorylation within the peptides were determined by solid phase Edman sequencing on an Applied Biosystems Procise 494C after coupling the peptide covalently with a Sequelon-arylamine membrane and measuring by Cerenkov counting the 32P radioactivity released after each cycle.

Cell culture and lysis

HEK-293 cells were cultured in DMEM (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium) containing 10% (v/v) foetal bovine serum (Sigma), 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 units/ml penicillin G and 50 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen). HEK-293 cells were transfected using a modified poly(ethyleneimine)-based method as described in [37]. ES cells (embryonic stem cells) were cultured on gelatinized plates in DMEM containing 15% (v/v) serum (Hyclone), 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 50 units/ml penicillin G, 50 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen) and 1000 units/ml LIF (leukaemia inhibitory factor) as described in [38] and transfected using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen).

Before stimulation, cells were serum starved in DMEM containing L-glutamine, penicillin and streptomycin for 16 h (HEK-293 cells), 24 h (PC12 cells) or 4 h (ES cells). Where indicated, cells were then incubated for an additional hour in the presence of cell-permeable kinase inhibitors, except for wortmannin when a 10 min incubation was used, before stimulations were started. Cells were then stimulated with PMA (400 ng/ml), EGF (100 ng/ml), anisomycin (10 μg/ml), IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor 1; 100 ng/ml) or NGF (50 ng/ml) for the times indicated. Cells were then lysed in 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 50 mM sodium fluoride, 1 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 0.27 M sucrose, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol and complete proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Roche, East Sussex, U.K.). The lysates were centrifuged at 18000 g for 5 min at 4 °C and the supernatants were removed, quick frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until use.

Nur77 antibodies

Antibodies were raised in sheep against phospho-Ser354 Nur77 using the peptide CGRLP(phospho-S)KPKQP (corresponding to the phosphorylated Ser354 site of mouse Nur77), total Nur77 using the peptide RDHLTGDPLALEFGK (residues 18–32 of mouse Nur77), total Nurr1 using the peptide SGEYSSDFLTPEFVK (27–41 of mouse Nurr1) and total Nor1 using the peptide CPRPLIKMEEGREHG (84–97 of mouse Nor1). Antibodies were purified on columns corresponding to the immunogenizing peptide. These antibodies were used at final concentrations of 1 μg/ml for immunoblotting. The phospho-Ser354 antibody was preincubated in the presence of 10 μg/ml of the dephospho-peptide in 5% milk TBS-T [Tris buffered saline +0.1 % (v/v) Tween] for 30 min before use.

Immunoprecipitation of Nur77

Nur77 was immunoprecipitated from the indicated amount of cell lysate using either 5 μg of an antibody raised against Nur77 or 1 μg of an antibody against the FLAG tag coupled with Protein G–Sepharose for 2 h at 4 °C. Immunoprecipitates were pelleted by centrifugation for 1 min at 13000 g and washed twice in 50 mm Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EGTA and 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol and once in 50 mm Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 0.1 mM EGTA and 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol. Protein was eluted in 1×SDS sample buffer (Invitrogen).

Immunoblotting

Samples were run on 4–12% polyacrylamide gels (Novex, Invitrogen) and transferred on to nitrocellulose membranes. Antibodies that recognize ERK (extracellular-signal-regulated kinase), phospho-ERK, phospho-Thr308 PKB, phospho-GSK3 (glycogen synthase kinase-3), phospho-Thr359 RSK, SAPK2, and phospho-SAPK2/p38 were from New England Biolabs (Hitchin, U.K.). HRP (horseradish peroxidase)-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Pierce (Cheshire, U.K.), and detection was performed using the enhanced chemiluminescence reagent from Amersham Biosciences (Little Chalfont, Bucks., U.K.).

14-3-3 overlay

Proteins were separated on 4–12% polyacrylamide gels (Novex, Invitrogen) and transferred on to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were then treated as for immunoblots; however, DIG (digoxigenin)-labelled 14-3-3 proteins were used in place of primary antibody, followed by a secondary anti-DIG–HRP antibody.

Luciferase assays

Cells were transfected with the appropriate NurRE or NBRE promoter vectors [10] and NR4A expression vector along with a Renilla luciferase vector as a transfection control. Cells were serum starved for 16 h, 24 h after transfection. Cells were then left untreated or stimulated with 400 ng/ml PMA for the times indicated. Cells were then lysed and the activities of firefly and Renilla luciferase were measured using the Dual-Glo system (Promega). Luciferase activities were then normalized to the appropriate Renilla control.

RESULTS

Nur77 is phosphorylated on Ser354 by RSK and MSK1 in vitro

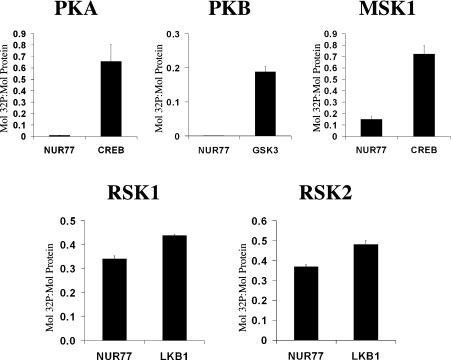

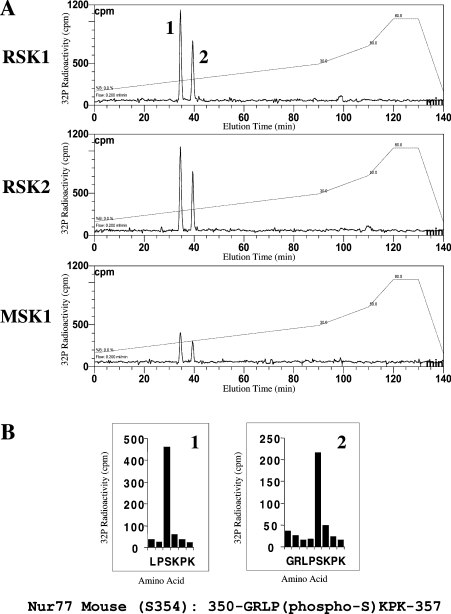

The ability of PKB, PKA, RSK1, RSK2 and MSK1 to phosphorylate Nur77 in vitro was examined using GST-tagged full-length Nur77 expressed in E. coli (Figure 1). PKB and PKA failed to phosphorylate Nur77 in vitro, although they were able to efficiently phosphorylate other known substrates [GSK3 or CREB (cyclic AMP response element binding protein) respectively]. MSK1 was able to weakly phosphorylate Nur77; however, the rate of phosphorylation of Nur77 by MSK1 was much less than the rate for the phosphorylation of CREB, a known substrate of MSK1. Both RSK1 and RSK2 were able to efficiently phosphorylate Nur77 in vitro (Figure 1). To map the phosphorylation site in Nur77, GST-tagged Nur77 was phosphorylated with 32P-labelled ATP by RSK1, RSK2 or MSK1. The GST–Nur77 was then digested with trypsin and the peptides were then run on reverse phase HPLC. The phospho-peptide HPLC traces for Nur77 phosphorylated by RSK, RSK2 or MSK were identical, all showing two peaks of radioactivity, consistent with all three kinases phosphorylating the same sites (Figure 2A). Analysis of these peptides by MS showed that they corresponded to the peptides LPSKPK and GRLPSKPK, residues 352–358 and 351–358 of murine Nur77 respectively. The second peptide was the result of trypsin failing to cleave at Arg351. Solid phase sequencing of the peptides phosphorylated by RSK1 and RSK2 confirmed the phosphorylated residue as Ser354 of mouse Nur77 (Figure 2B).

Figure 1. In vitro phosphorylation of Nur77.

Recombinant GST–Nur77 (2 μg) was phosphorylated using 20 m-units of PKA, MSK1, PKB, RSK1 or RSK2 for 40 min. In parallel experiments, to confirm the activity of the kinase, 2 μg of CREB was phosphorylated by PKA or MSK1, 2 μg of LKB1 was phosphorylated by RSK1 or RSK2 and 2 μg of GSK3 was phosphorylated by PKB. Reactions were then run on SDS/polyacrylamide gels, and bands corresponding to Nur77, CREB, LKB1 and GSK3 were excised and the incorporation of 32P was measured by Cerenkov counting and expressed as mol of 32P incorporated per mol of protein. Error bars represent the S.D. for three points.

Figure 2. Mapping of RSK and MSK1 phosphorylation sites on Nur77.

Purified E. coli-expressed GST–Nur77 was phosphorylated by MSK1, RSK1 or RSK2 as in Figure 1. Samples were run on a 4–12% polyacrylamide gel, and the band corresponding to Nur77 was excised and the protein was reduced with dithiothreitol, alkylated with 4-vinylpyridine and digested with trypsin. The resulting peptides were applied to a Vydac 218TP5215 C18 column equilibrated in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and the column was developed with a linear gradient (A, broken line) of acetonitrile/0.1% trifluoroacetic acid at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min while collecting 0.1 ml fractions. 32P radioactivity (A, continuous line) was recorded with an on-line monitor. Solid phase sequencing data from the phosphorylation of Nur77 by RSK2 are shown in (B); identical results were obtained for the phosphorylation of Nur77 by RSK1.

To allow analysis of the phosphorylation state of this residue in vivo, a phospho-specific antibody was raised against the peptide CGRLP(phospho-S)KPKQP. The antibody was found to be specific for the phosphorylated form of this peptide (Supplementary Figure 1 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/393/bj3930715add.htm).

NR4A proteins are phosphorylated by RSK but not MSK1 or PKB in vivo

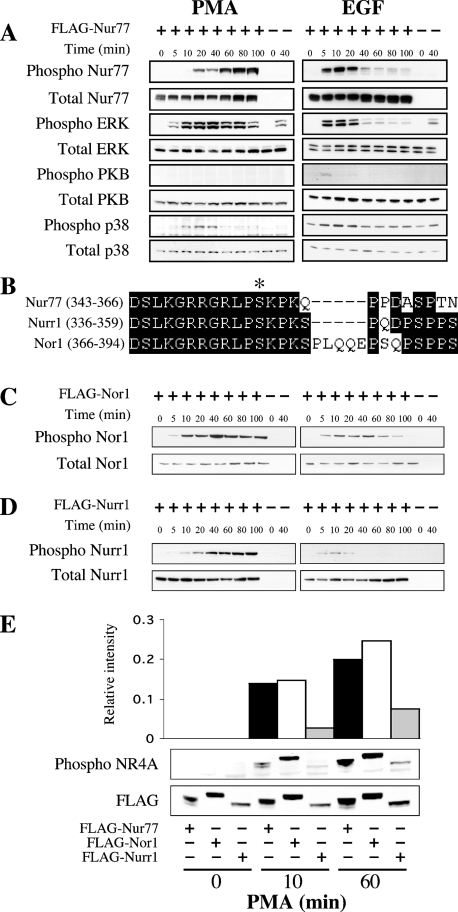

To analyse the phosphorylation of Nur77 in cells, FLAG-tagged full-length Nur77 was expressed in HEK-293 cells by transient transfection. Various stimuli were then used to examine the role of RSK (which is activated in vivo via the ERK1/2 pathway), MSK (which is activated in vivo by ERK1/2 and/or p38α), PKA and PKB in the phosphorylation of Nur77 in vivo. Stimulation of cells with IGF-1 was found to strongly activate PKB; however, it did not stimulate phosphorylation of Nur77 on Ser354 (Supplementary Figure 2 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/393/bj3930715add.htm). Anisomycin is a strong activator of the p38 MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) cascade that results in the activation of MSK1; however, anisomycin does not activate the ERK1/2 cascade and is therefore unable to activate RSK [29]. Anisomycin was however unable to stimulate Nur77 Ser354 phosphorylation (Supplementary Figure 2). PMA strongly activates the ERK1/2 cascade, and is known to activate both MSK and RSK downstream of ERK1/2 in HEK-293 cells [29]. PMA treatment did result in a weak activation of the p38 cascade, but did not significantly activate PKB (Figure 3A). PMA was found to stimulate phosphorylation of Nur77 on Ser354 as judged by blotting with a Ser354 phospho-specific antibody. The kinetics of phosphorylation of Nur77 Ser354 did not exactly mirror ERK1/2 activation, as although ERK1/2 was activated quickly after PMA stimulation and then remained high, Nur77 phosphorylation was found to accumulate over the time course of the stimulation. EGF also activates ERK1/2 in HEK-293 cells, although the stimulation was faster but more transient than with PMA. EGF was also seen to weakly activate PKB but did not significantly activate p38 in these cells. EGF was found to stimulate phosphorylation of Nur77 on Ser354 with similar kinetics to that of ERK1/2 activation (Figure 3A). The sequence around Ser354 in Nur77 is highly conserved in the related nuclear orphan receptors, Nurr1 (Ser347) and Nor1 (Ser377; Figure 3B). We therefore tested these proteins to see if they were phosphorylated on the equivalent site in cells. Similar to Nur77, when FLAG–Nor1 was expressed in HEK-293 cells, its phosphorylation on Ser377 was stimulated by both PMA and EGF (Figure 3C). FLAG–Nurr1 was phosphorylated on Ser347 after PMA or EGF stimulation as judged by immunoblotting, although the level of phosphorylation appeared to be lower than for Nur77 or Nor1 (Figure 3D). To test this, samples from PMA-stimulated HEK-293 cells transfected with FLAG–Nur77, FLAG–Nor1 or FLAG–Nurr1 were run on the same gels and blotted with either the phospho-specific antibody or an antibody against the FLAG peptide. The blots were analysed on a Licor Odyssey system and the phospho signal was quantified relative to the signal for the FLAG tag. This suggested that Nur77 and Nor1 were phosphorylated to similar levels, but that Nurr1 was phosphorylated at approx. 4-fold lower levels (Figure 3E). As the phospho-peptide antibody was raised against the sequence CGRLP(phospho-S)KPKQP, which is highly conserved in Nur77, Nurr1 and Nor1, it would be expected to recognize all three isoforms with a similar affinity. However, the possibility that Nurr1 may be recognized with a lower affinity by the antibody than the other isoforms cannot be excluded.

Figure 3. Nur77 Ser354 phosphorylation is stimulated in vivo by PMA and EGF.

(A) HEK-293 cells were transfected with an expression plasmid for FLAG–Nur77. Cells were then starved for 16 h and stimulated with either 400 ng/ml PMA or 100 ng/ml EGF for the times indicated. Cells were then lysed and 30 μg of soluble protein lysate was run on 4–12% gradient polyacrylamide gels. The levels of phospho-Ser354 Nur77, total Nur77, phospho-ERK1/2, total ERK1/2, phospho-Thr308 PKB, total PKB, phospho p38 and total p38 were then examined by immunoblotting. (B) Sequence alignment of murine Nur77 (GenBank® accession no. P12813), Nurr1 (GenBank® accession no. A46225) and Nor1 (Genbank® accession no. Q9QZB6) around the RSK phosphorylation site. (C) HEK-293 cells were transfected with an expression plasmid for FLAG–Nor1. Cells were then starved for 16 h and stimulated with either 400 ng/ml PMA or 100 ng/ml EGF for the times indicated. Cells were then lysed and 30 μg of soluble protein lysate was run on 4–12% gradient polyacrylamide gels. The levels of phospho-Ser377 Nor1 and total Nor1 were determined by immunoblotting. (D) HEK-293 cells were transfected with an expression plasmid for FLAG–Nurr1. Cells were then starved for 16 h and stimulated with either 400 ng/ml PMA or 100 ng/ml EGF for the times indicated. Cells were then lysed and 30 μg of soluble protein lysate was run on 4–12% gradient polyacrylamide gels. The levels of phospho-Ser347 Nurr1 and total Nurr1 were determined by immunoblotting. (E) Samples from unstimulated or PMA-stimulated cells transfected with FLAG–Nur77, FLAG–Nor1 or FLAG–Nurr1 were run on 4–12% gradient polyacrylamide gels and immunoblotted using either an anti-FLAG antibody or the anti phospho-Ser354 Nur77 antibody. Blots were visualized using fluorescent labelled secondary antibodies and the signal was quantified using a Licor Odyssey scanner. The level of the phospho signal was then calculated relative to the signal for FLAG.

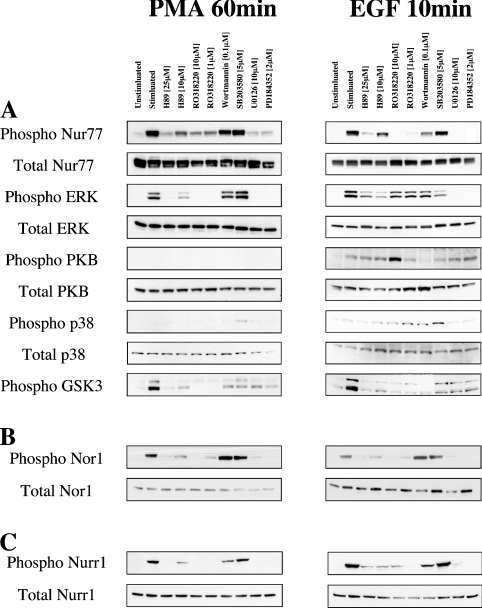

To confirm which pathway was for these phosphorylations. Consistent with this, Ro 318220, a compound originally developed as a PKC inhibitor but which has also been shown to be a potent inhibitor of both RSK and MSK1 [39], was also able to block Nur77 Ser354 phosphorylation in response to EGF. Ro 318220 also inhibited this phosphorylation in response to PMA; however, in this case, Ro 318220 also blocked the activation of ERK1/2, presumably due to the requirement for PKC to mediate PMA-induced activation of the classical MAPK cascade. H89 (an inhibitor of PKA which can also inhibit both MSK1 and RSK at the concentrations used) at 25 mM, and to a lesser extent at 10 mM, was also able to inhibit the phosphorylation of Nur77 on Ser354 in response to EGF. These concentrations of H89 were also able to inhibit the RSK-dependent phosphorylation of GSK3 in response to PMA and EGF, confirming that RSK was inhibited under these conditions. H89 also inhibited PMA-induced Nur77 phosphorylation, but in this case activation of ERK1/2 was also inhibited. SB203580, an inhibitor of p38α/β, did not block the phosphorylation of Nur77 on Ser354 in response to PMA or EGF. Wortmannin, an inhibitor of PI3K that blocks the activation of PKB, did not affect the phosphorylation of Nur77 on Ser354 in response to PMA, although it did slightly inhibit Nur77 phosphorylation in response to EGF (Figure 4A). This may be because wortmannin also slightly reduced the activation of the ERK1/2 cascade in response to EGF. Similar results were also obtained for Nor1 (Figure 4B) and Nurr1 (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Inhibition of Nur77 Ser354 phosphorylation.

(A) HEK-293 cells were transfected with an expression plasmid for FLAG–Nur77. Cells were then starved for 16 h and incubated with H89, Ro 318220, wortmannin, SB 203580, U0126 or PD 184352 at the concentrations indicated. Cells were then stimulated with either 400 ng/ml PMA for 60 min or 100 ng/ml EGF for 10 min. Cells were then lysed and 30 μg of soluble protein lysate was run on 4–12% gradient polyacrylamide gels. The levels of phospho-Ser354 Nur77, total Nur77, phospho-ERK1/2, total ERK1/2, phospho-Thr308 PKB, total PKB, phospho-p38 and total p38 were then examined by immunoblotting. (B) Experiments were performed as described in (A) except that FLAG–Nor1 was transfected instead of Nur77 and levels of phosphorylated and total Nor1 were measured by immunoblotting. (C) Experiments were performed as described in (A) except that FLAG–Nurr1 was transfected instead of Nur77 and levels of phosphorylated and total Nurr1 were measured by immunoblotting.

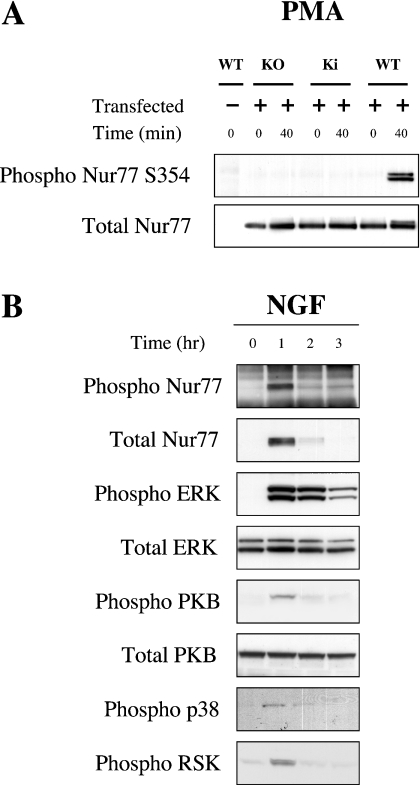

To distinguish between MSK and RSK activity, mouse ES cells that expressed a mutated form of PDK1 (phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1) were used [40]. PDK1 knockout ES cells have previously been shown to be unable to activate RSK or PKB. In contrast, activation of MSK1 is unaffected by the knockout of PDK1. A targeted mutation of the PDK1 gene, L155E, has been shown to interfere with the binding of PDK1 to RSK. In ES cells homozygous for this mutation, it has been shown that RSK is inactive but that the activation of PKB is normal [41]. Wild-type ES cells were able to phosphorylate expressed Nur77 on Ser354 in response to PMA. In contrast, PDK1 knockout or L155E PDK1 mutant cells were unable to phosphorylate Ser354 of Nur77 (Figure 5A), confirming a role for RSK in this phosphorylation.

Figure 5. Phosphorylation of Nur77 in ES and PC12 cells.

(A) Wild-type, PDK1 knockout and PDK1 L155E knockin ES cells were transfected with FLAG–Nur77. Cell were starved for 4 h and then stimulated with 400 ng/ml PMA for 0 or 40 min. Cells were then lysed and Nur77 was immunoprecipitated from 2 mg of cell lysate using an antibody against the FLAG tag. Immunoprecipitates were then run on 4–12% gradient polyacrylamide gels, and the levels of phospho-Ser354 Nur77 and total Nur77 were determined by immunoblotting. (B) PC12 cells were serum starved for 24 h and then either left unstimulated or stimulated with 50 ng/ml NGF for the times indicated; cells were then lysed and the levels of phospho- and total ERK1/2, phospho-p38, phospho-RSK, and phospho- and total PKB were determined by immunoblotting. Endogenous Nur77 was immunoprecipitated from 3 mg of lysate and immunoblotted for total and phospho-Ser354 Nur77.

To determine if endogenous Nur77 was phosphorylated on Ser354, PC12 cells were treated with NGF to induce production of Nur77 protein. After 1 h of NGF stimulation, endogenous Nur77 protein had been induced, and this endogenous protein was phosphorylated as judged by immunoblotting with the phospho-specific Nur77 antibody. PMA and NGF were also able to activate ERK1/2 and RSK, phosphorylation of Nur77 at Ser354, consistent with phosphorylation of this site by RSK (Figure 5B). As inhibitors such as PD 184352, which block the activation of RSK, also block the production of endogenous Nur77 protein by these stimuli, they could not be used to examine the role of RSK in endogenous Nur77 phosphorylation.

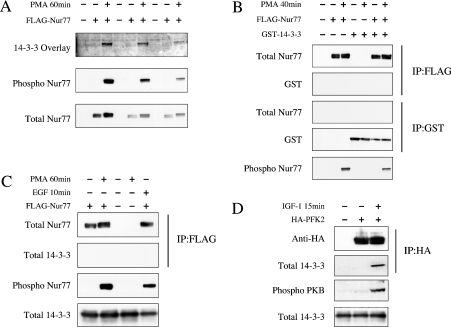

RSK promotes the association of Nur77 with 14-3-3 proteins in vitro

Ser354 in Nur77 lies within a potential binding site for 14-3-3 proteins, so the ability of RSK to promote the interaction of Nur77 with 14-3-3 proteins was tested. FLAG–Nur77 expressed in HEK-293 cells was immunoprecipitated and used in a 14-3-3 overlay experiment. FLAG–Nur77 from unstimulated cells, which was not phosphorylated on Ser354 as judged by immunoblotting with the phospho-Ser354-specific antibody, did not interact with 14-3-3 proteins in the overlay experiment. In contrast, FLAG–Nur77 from PMA-stimulated cells was phosphorylated on Ser354, and was able to bind 14-3-3 protein in the overlay experiment (Figure 6A). Despite this, we were unable to detect an association of Nur77 and 14-3-3 proteins in cells. FLAG–Nur77 was co-transfected into HEK-293 cells with GST–14-3-3ζ. After stimulation and lysis, FLAG–Nur77 was immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG antibody, or the GST–14-3-3 was pulled down with glutathione–Sepharose from the cell lysates. No co-precipitation of Nur77 and 14-3-3 was observed before or after stimulation with PMA (Figure 6B). We could also not detect any co-immunoprecipitation of FLAG–Nur77 with endogenous 14-3-3 proteins in either unstimulated or PMA- or EGF-stimulated cells, even though both these stimuli clearly induced Nur77 phosphorylation (Figure 6C). Parallel experiments co-transfecting PFK2 (a known 14-3-3-binding protein [42]) showed that this protein immunoprecipitated with endogenous 14-3-3 proteins after IGF treatment (Figure 6D).

Figure 6. Phosphorylation of Nur77 promotes 14-3-3 binding.

(A) FLAG–Nur77 was transfected into HEK-293 cells, which were then serum starved for 16 h. The cells were then left unstimulated or stimulated with 400 ng/ml PMA for 60 min. FLAG–Nur77 was immunoprecipitated from 0.5 mg of lysate and immunoprecipitates were blotted for total and phospho-Ser354 Nur77. 14-3-3 overlays were performed as described in the Materials and methods section. (B) HEK-293 cells were transfected with FLAG–Nur77 and/or GST–14-3-3 as indicated. After transfection, cells were serum starved for 16 h and either treated with 400 ng/ml PMA for 40 min or left unstimulated. Cells were lysed and Nur77 immunoprecipitated using anti-FLAG antibodies or 14-3-3 pulled down using glutathione–Sepharose as indicated, and precipitates were immunoblotted for Nur77 or GST. Total cell lysates was immunoblotted for phospho-Ser354 Nur77. (C) FLAG–Nur77 was transfected into HEK-293 cells, which were then serum starved for 16 h. The cells were then left unstimulated or stimulated with 400 ng/ml PMA for 60 min. FLAG–Nur77 was immunoprecipitated from 0.5 mg of lysate and immunoprecipitates were blotted for either total Nur77 or 14-3-3 (using a pan 14-3-3). Cell lysates were also blotted for phospho-Ser354 Nur77 and total 14-3-3. (D) HA–PFK was transfected into HEK-293 cells, which were then starved for 16 h and then stimulated with IGF (10 ng/ml) for 15 min. HA–PFK2 was immunoprecipitated using an HA antibody and the immunoprecipitates were blotted using a pan 14-3-3 or HA antibody. Cell lysates were also blotted for phospho-PKB and total 14-3-3.

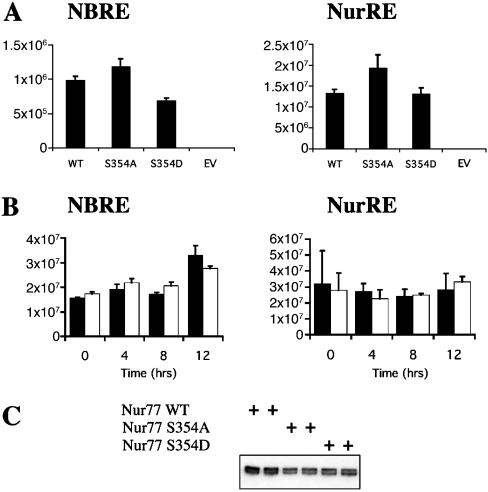

Ser354 modification does not affect protein stability or transcriptional activity

To further examine a role for Ser354 phosphorylation, this residue was mutated either to alanine (to block phosphorylation) or aspartic acid (to mimic phosphorylation). As Nur77 is a short-lived protein in cells, the possibility that modification of Ser354 may stabilize the Nur77 protein was investigated. Ser354 was mutated to either an alanine or aspartic acid, and the mutated proteins were expressed in HEK-293 cells. Cells were then treated with cyclohexamide to block protein synthesis, and the levels of Nur77 were monitored over time. Wild-type mutated Nur77 was found to have a half-life of 2 h after cyclohexamide addition and this was not significantly changed by mutation of Ser354 (Supplementary Figure 3 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/393/bj3930715add.htm).

To determine the role of Ser354 in controlling the transcriptional activity of nut77, the proteins were co-transfected into HEK-293 cells with luciferase reporter vectors whose promoters contained either NBREs or NurREs. The basal activity of both these vectors in the absence of co-transfected Nur77 was low (Figure 7A). The basal activity of the NBRE reporter was slightly stimulated by PMA or EGF (∼2-fold); however, the basal activity of the NurRE was unaffected (results not shown). Co-transfection of a wild-type Nur77 expression vector was able to significantly promote transcription from both these reporter vectors compared with co-transfection of an empty vector (Figure 7A). Mutation of Ser354 to alanine slightly increased the transcriptional activity of Nur77, while mutation of Ser354 to aspartic acid resulted in a slightly lower transcriptional activity than the S354A mutant Nur77 (Figure 7A). Analysis of the expression levels of the different Nur77 mutants showed that they had similar expression levels, although the wild-type Nur77 was expressed at slightly higher levels. PMA stimulation of cells co-transfected with the NurRE luciferase reporter with either wild-type Nur77 or S354A Nur77 did not affect the activity of the reporter vectors (Figure 7B). For the NBRE reporter co-transfected with Nur77, PMA stimulation did, however, result in a slight increase in activity at later time points. This effect was still, however, seen with the S354A mutant Nur77, and is therefore unlikely to reflect a role for phosphorylation of this site.

Figure 7. Activation of NBRE and NurRE reporter plasmids.

(A) HEK-293 cells were transfected with a Renilla luciferase (to control for transfection efficiency) and NBRE or NurRE luciferase reporters along with either empty vector or expression vectors for wild-type (WT), S354A or S354D or an empty vector (EV) as indicated. Cells were lysed and luciferase activity was measured and normalized for the Renilla control. Error bars represent the S.E.M. for 16 (NBRE) or 20 (NurRE) replicates. (B) Experiments were performed as described in (A) except that cells were serum starved for 16 h and then stimulated with PMA (400 ng/ml) for 0–8 h as indicated. Black bars represent wild-type Nur77 and white bars represent S354A Nur77. Error bars represent the S.E.M. for 16 (NBRE) or 20 (NurRE) replicates. (C) Anti-FLAG immunoblot showing the relative expression levels of the Nur77 wild-type and Ser354 mutant constructs in HEK-293 cells.

DISCUSSION

Several previous studies have shown that Nur77 can be phosphorylated on multiple sites and that one of these sites is Ser354. Several kinases have been suggested as potential Nur77 kinases; however, the physiological kinase responsible for this phosphorylation has yet to be clearly established. In the present study, we show that two kinases, RSK and MSK1, can phosphorylate Nur77 in vitro. Mapping of the phosphorylation sites in Nur77 showed that RSK phosphorylated Nur77 at Ser354 and did not cause significant phosphorylation of any other site. In contrast with previous reports [2,26,33], we were unable to show phosphorylation of Nur77 by PKA or PKB, although both these kinases efficiently phosphorylated known substrates, CREB or GSK3 respectively, in parallel assays. One explanation for this may be that both previous studies used only the DNA-binding domain of Nur77 as an in vitro substrate, and did not report the degree of phosphorylation. In the present study, we used the full-length Nur77 protein and 32P labelling to allow us to determine the extent of Nur77 phosphorylation.

We also examined how Nur77 phosphorylation could occur in vivo. Consistent with our in vitro findings, IGF1 (Supplementary Figure 2) and forskolin (results not shown), strong activating stimuli for PKB and PKA respectively, were unable to stimulate phosphorylation of Nur77 in vivo. Anisomycin, which activates MSK1 via the p38 MAPK cascade, was also unable to stimulate Nur77 phosphorylation, arguing against MSK1 being a physiological Nur77 kinase. PMA and EGF were able to stimulate Nur77 Ser354 phosphorylation, and this could be blocked by inhibitors of the ERK1/2 cascade. Using a combination of inhibitors, and ES cell lines that activate PKB and MSK but not RSK, we were able to show that RSK is the kinase responsible for the phosphorylation of Nur77 on Ser354 (Figures 4 and 5).

Previous studies on the DNA binding domain have shown that phosphorylation of Ser354 inhibits DNA binding in vitro [43], possibly due to the introduction of a negative charge which would be close to the DNA backbone in a Nur77/DNA complex. Surprisingly however, phosphorylation of Ser354, or its mutation to an acidic residue, did not greatly affect the ability of Nur77 to drive transcription from NurRE- or NBRE-dependent reporter vectors. The reason for this is not clear; however, it could be that even weak or more transient DNA binding by Nur77 is sufficient to drive expression from these vectors when Nur77 is overexpressed and that the overexpression system is not sensitive enough to detect these changes. It is also possible that phosphorylation of Nur77 by RSK could affect other aspects of Nur77 function which would not necessarily show an effect on transcription of a synthetic reporter. Phosphorylation of Nur77 on Ser354 creates a consensus 14-3-3-binding site, and this is able to bind 14-3-3 in vitro. We were unable to co-immunoprecipitate phospho Nur77 and 14-3-3 from lysates, suggesting that these proteins may not interact in cells. The interaction of 14-3-3 proteins with their targets can, however, be weak and, as a result, hard to detect by co-immunoprecipitation. As a result, the possibility that RSK may promote the interaction of Nur77 and 14-3-3 proteins in cells cannot be completely excluded. Phosphorylation of Nur77 on Ser354 may also affect the ability of Nur77 to interact with other proteins. For instance, Nur77 has been reported to interact with other transcription factors including NF-κB (nuclear factor κB) and glucocorticoid receptors, and in both cases Nur77 is proposed to repress the activity of these transcription factors [44,45]. Nur77 has also been shown to interact with RXR (retinoid X receptor) nuclear receptors; however, in this case, the interaction with RXR appears to cause the cytoplasmic translocation of Nur77 and promote apoptosis [46,47]. Another possibility is that in addition to phosphorylation of Nur77, the binding of RSK to Nur77 may be able to allosterically activate Nur77. A similar mechanism has been suggested for the oestrogen receptor. Binding of RSK to the hormone-binding domain of the oestrogen receptor has been shown to activate the oestrogen receptor independently of its phosphorylation by RSK, although in this case phosphorylation was found to enhance this effect [48].

The NR4A genes are all immediate early genes that can be induced by MAPK signalling, and can be phosphorylated by the ERK1/2-activated kinase p90RSK in cells. For phosphorylation of endogenous Nur77, Nor1 or Nurr1, it is possible that prolonged activation of ERK is required, in order for RSK still to be active by the time NR4A proteins are translated. A similar situation has been described for another RSK substrate, c-fos. Like the NR4A genes, c-fos is a MAPK-controlled immediate early gene and it has been found that transient activation of ERK is sufficient to induce c-Fos protein, but prolonged ERK1/2 activation is required for its phosphorylation by p90Rsk [49]. This has been proposed as a possible explanation for why transient or prolonged ERK1/2 activation can have different cellular outcomes. In the case of c-Fos, phosphorylation stabilizes the protein; however, the function of NR4A phosphorylation is still unclear.

Online Data

Acknowledgments

We thank Dario Alessi and Barry Collins (University of Dundee) for the PDK1 ES cell lines, Nick Morrice for assistance with MS, Joanne McIlrath for help with antibody characterization and Rachael Toth for help with DNA cloning. The NurRE and NBRE vectors were a gift from Jacques Drouin (Institut de Recherches Cliniques de Montreal, Quebec, Canada). Antibodies were purified by the DSTT antibody production team. This research was supported by grants from the U.K. Medical Research Council, Astra-Zeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Merk and Co, Merk KGaA and Pfizer.

References

- 1.Winoto A., Littman D. R. Nuclear hormone receptors in T lymphocytes. Cell (Cambridge, Mass.) 2002;109:S57–S66. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00710-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masuyama N., Oishi K., Mori Y., Ueno T., Takahama Y., Gotoh Y. Akt inhibits the orphan nuclear receptor Nur77 and T-cell apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:32799–32805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105431200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winoto A. Molecular characterization of the Nur77 orphan steroid receptor in apoptosis. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 1994;105:344–346. doi: 10.1159/000236780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Youn H. D., Liu J. O. Cabin1 represses MEF2-dependent Nur77 expression and T cell apoptosis by controlling association of histone deacetylases and acetylases with MEF2. Immunity. 2000;13:85–94. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng L. E., Chan F. K., Cado D., Winoto A. Functional redundancy of the Nur77 and Nor-1 orphan steroid receptors in T-cell apoptosis. EMBO J. 1997;16:1865–1875. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li H., Kolluri S. K., Gu J., Dawson M. I., Cao X., Hobbs P. D., Lin B., Chen G., Lu J., Lin F., et al. Cytochrome c release and apoptosis induced by mitochondrial targeting of nuclear orphan receptor TR3. Science. 2000;289:1159–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5482.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin B., Kolluri S. K., Lin F., Liu W., Han Y. H., Cao X., Dawson M. I., Reed J. C., Zhang X. K. Conversion of Bcl-2 from protector to killer by interaction with nuclear orphan receptor Nur77/TR3. Cell (Cambridge, Mass.) 2004;116:527–540. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00162-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suzuki S., Suzuki N., Mirtsos C., Horacek T., Lye E., Noh S. K., Ho A., Bouchard D., Mak T. W., Yeh W. C. Nur77 as a survival factor in tumor necrosis factor signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:8276–8280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932598100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolluri S. K., Bruey-Sedano N., Cao X., Lin B., Lin F., Han Y. H., Dawson M. I., Zhang X. K. Mitogenic effect of orphan receptor TR3 and its regulation by MEKK1 in lung cancer cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:8651–8667. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.23.8651-8667.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Philips A., Lesage S., Gingras R., Maira M. H., Gauthier Y., Hugo P., Drouin J. Novel dimeric Nur77 signaling mechanism in endocrine and lymphoid cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:5946–5951. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.10.5946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chintharlapalli S., Burghardt R., Papineni S., Ramaiah S., Yoon K., Safe S. Activation of Nur77 by selected 1,1-bis(3′-indolyl)-1-(p-substitutedphenyl) methanes induces apoptosis through nuclear pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:24903–24914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paulsen R. F., Granas K., Johnsen H., Rolseth V., Sterri S. Three related brain nuclear receptors, NGFI-B, Nurr1, and NOR-1, as transcriptional activators. J. Mol. Neurosci. 1995;6:249–255. doi: 10.1007/BF02736784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Z., Benoit G., Liu J., Prasad S., Aarnisalo P., Liu X., Xu H., Walker N. P., Perlmann T. Structure and function of Nurr1 identifies a class of ligand-independent nuclear receptors. Nature (London) 2003;423:555–560. doi: 10.1038/nature01645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flaig R., Greschik H., Peluso-Iltis C., Moras D. Structural basis for the cell-specific activities of the NGFI-B and the Nurr1 ligand-binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:19250–19258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413175200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoon J. K., Lau L. F. Transcriptional activation of the inducible nuclear receptor gene nur77 by nerve growth factor and membrane depolarization in PC12 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:9148–9155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams G. T., Lau L. F. Activation of the inducible orphan receptor gene nur77 by serum growth factors: dissociation of immediate-early and delayed-early responses. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1993;13:6124–6136. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.6124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darragh J., Soloaga A., Beardmore V. A., Wingate A., Wiggin G. R., Peggie M., Arthur J. S. MSKs are required for the transcription of the nuclear orphan receptors Nur77, Nurr1 and Nor1 downstream of MAP kinase signalling. Biochem. J. 2005;390:749–759. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Der Heide L. P., Hoekman M. F., Smidt M. P. The ins and outs of FoxO shuttling: mechanisms of FoxO translocation and transcriptional regulation. Biochem. J. 2004;380:297–309. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayr B., Montminy M. Transcriptional regulation by the phosphorylation-dependent factor CREB. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:599–609. doi: 10.1038/35085068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharrocks A. D. The ETS-domain transcription factor family. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:827–837. doi: 10.1038/35099076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katagiri Y., Takeda K., Yu Z. X., Ferrans V. J., Ozato K., Guroff G. Modulation of retinoid signalling through NGF-induced nuclear export of NGFI-B. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:435–440. doi: 10.1038/35017072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slagsvold H. H., Ostvold A. C., Fallgren A. B., Paulsen R. E. Nuclear receptor and apoptosis initiator NGFI-B is a substrate for kinase ERK2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;291:1146–1150. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirata Y., Whalin M., Ginty D. D., Xing J., Greenberg M. E., Guroff G. Induction of a nerve growth factor-sensitive kinase that phosphorylates the DNA-binding domain of the orphan nuclear receptor NGFI-B. J. Neurochem. 1995;65:1780–1788. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65041780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meinke G., Sigler P. B. DNA-binding mechanism of the monomeric orphan nuclear receptor NGFI-B. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1999;6:471–477. doi: 10.1038/8276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fahrner T. J., Carroll S. L., Milbrandt J. The NGFI-B protein, an inducible member of the thyroid/steroid receptor family, is rapidly modified posttranslationally. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1990;10:6454–6459. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.12.6454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katagiri Y., Hirata Y., Milbrandt J., Guroff G. Differential regulation of the transcriptional activity of the orphan nuclear receptor NGFI-B by membrane depolarization and nerve growth factor. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:31278–31284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arthur J. S., Cohen P. MSK1 is required for CREB phosphorylation in response to mitogens in mouse embryonic stem cells. FEBS Lett. 2000;482:44–48. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiggin G. R., Soloaga A., Foster J. M., Murray-Tait V., Cohen P., Arthur J. S. MSK1 and MSK2 are required for the mitogen- and stress-induced phosphorylation of CREB and ATF1 in fibroblasts. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:2871–2881. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.8.2871-2881.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deak M., Clifton A. D., Lucocq L. M., Alessi D. R. Mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase-1 (MSK1) is directly activated by MAPK and SAPK2/p38, and may mediate activation of CREB. EMBO J. 1998;17:4426–4441. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.15.4426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fisher T. L., Blenis J. Evidence for two catalytically active kinase domains in pp90rsk. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:1212–1219. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis I. J., Hazel T. G., Chen R. H., Blenis J., Lau L. F. Functional domains and phosphorylation of the orphan receptor Nur77. Mol. Endocrinol. 1993;7:953–964. doi: 10.1210/mend.7.8.8232315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swanson K. D., Taylor L. K., Haung L., Burlingame A. L., Landreth G. E. Transcription factor phosphorylation by pp90(rsk2). Identification of Fos kinase and NGFI-B kinase I as pp90(rsk2) J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:3385–3395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pekarsky Y., Hallas C., Palamarchuk A., Koval A., Bullrich F., Hirata Y., Bichi R., Letofsky J., Croce C. M. Akt phosphorylates and regulates the orphan nuclear receptor Nur77. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:3690–3694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051003198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis I. J., Lau L. F. Endocrine and neurogenic regulation of the orphan nuclear receptors Nur77 and Nurr-1 in the adrenal glands. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:3469–3483. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.5.3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maira M., Martens C., Batsche E., Gauthier Y., Drouin J. Dimer-specific potentiation of NGFI-B (Nur77) transcriptional activity by the protein kinase A pathway and AF-1-dependent coactivator recruitment. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:763–776. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.3.763-776.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell D. G., Morrice N. Identification of protein phosphorylation sites by a combination of mass spectrometry and solid phase Edman sequencing. J. Biomed. Technol. 2002;13:119–130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCoy C. E., Campbell D. G., Deak M., Bloomberg G. B., Arthur J. S. MSK1 activity is controlled by multiple phosphorylation sites. Biochem. J. 2005;387:507–517. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arthur J. S., Elce J. S., Hegadorn C., Williams K., Greer P. A. Disruption of the murine calpain small subunit gene, Capn4: calpain is essential for embryonic development but not for cell growth and division. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:4474–4481. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.12.4474-4481.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davies S. P., Reddy H., Caivano M., Cohen P. Specificity and mechanism of action of some commonly used protein kinase inhibitors. Biochem. J. 2000;351:95–105. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3510095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams M. R., Arthur J. S., Balendran A., van der Kaay J., Poli V., Cohen P., Alessi D. R. The role of 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 in activating AGC kinases defined in embryonic stem cells. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:439–448. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00441-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Collins B. J., Deak M., Arthur J. S., Armit L. J., Alessi D. R. In vivo role of the PIF-binding docking site of PDK1 defined by knock-in mutation. EMBO J. 2003;22:4202–4211. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pozuelo Rubio M., Peggie M., Wong B. H., Morrice N., MacKintosh C. 14-3-3s regulate fructose-2,6-bisphosphate levels by binding to PKB-phosphorylated cardiac fructose-2,6-bisphosphate kinase/phosphatase. EMBO J. 2003;22:3514–3523. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hirata Y., Kiuchi K., Chen H. C., Milbrandt J., Guroff G. The phosphorylation and DNA binding of the DNA-binding domain of the orphan nuclear receptor NGFI-B. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:24808–24812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harant H., Lindley I. J. Negative cross-talk between the human orphan nuclear receptor Nur77/NAK-1/TR3 and nuclear factor-kappaB. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5280–5290. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martens C., Bilodeau S., Maira M., Gauthier Y., Drouin J. Protein-protein interactions and transcriptional antagonism between the subfamily of NGFI-B/Nur77 orphan nuclear receptors and glucocorticoid receptor. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005;19:885–897. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee K. W., Ma L., Yan X., Liu B., Zhang X. K., Cohen P. Rapid apoptosis induction by IGFBP-3 involves an insulin-like growth factor-independent nucleomitochondrial translocation of RXRalpha/Nur77. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:16942–16948. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412757200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cao X., Liu W., Lin F., Li H., Kolluri S. K., Lin B., Han Y. H., Dawson M. I., Zhang X. K. Retinoid X receptor regulates Nur77/TR3-dependent apoptosis by modulating its nuclear export and mitochondrial targeting. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:9705–9725. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.22.9705-9725.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clark D. E., Poteet-Smith C. E., Smith J. A., Lannigan D. A. Rsk2 allosterically activates estrogen receptor alpha by docking to the hormone-binding domain. EMBO J. 2001;20:3484–3494. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.13.3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murphy L. O., Smith S., Chen R. H., Fingar D. C., Blenis J. Molecular interpretation of ERK signal duration by immediate early gene products. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:556–564. doi: 10.1038/ncb822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.