Abstract

PPARγ (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ) is a nuclear receptor that is activated by natural lipid metabolites, including 15d-PGJ2 (15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2). We previously reported that several oxidized lipid metabolites covalently bind to PPARγ through a Michael-addition to activate transcription. To separate the ligand-entering (dock) and covalent-binding (lock) steps in PPARγ activation, we investigated the binding kinetics of 15d-PGJ2 to the PPARγ LBD (ligand-binding domain) by stopped-flow spectroscopy. We analysed the spectral changes of 15d-PGJ2 by multi-wavelength global fitting based on a two-step chemical reaction model, in which an intermediate state represents the 15d-PGJ2–PPARγ complex without covalent binding. The extracted spectrum of the intermediate state in wild-type PPARγ was quite similar to the observed spectrum of 15d-PGJ2 in the C285S mutant, which cannot be activated by 15d-PGJ2, indicating that the complex remains in the inactive, intermediate state in the mutant. Thus ‘lock’ rather than ‘dock’ is one of the critical steps in PPARγ activation by 15d-PGJ2.

Keywords: covalent binding; 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 (15d-PGJ2); Michael-addition; multi-wavelength global fitting analysis; peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ); stopped-flow spectroscopy

Abbreviations: DBD, DNA-binding domain; 15d-PGJ2, 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2; LBD, ligand-binding domain; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ; WT, wild-type

INTRODUCTION

PPARγ (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ) is a nuclear receptor that plays important roles in lipid homoeostasis, glucose metabolism and macrophage functions [1–3]. PPARγ is activated by several lipid metabolites, as well as their oxidized products [4–8]. Among them, 15d-PGJ2 (15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2) was the first endogenous molecule shown to activate PPARγ [4,5].

Generally, nuclear receptors are considered to undergo large conformational rearrangements in the LBD (ligand-binding domain) upon ligand binding, which leads to the recruitment of co-activators to regulate transcription [9,10]. This idea is supported by determination of the crystal structure of nuclear receptor LBDs, which revealed distinct conformations in the crystals. For example, PPARα when bound with an antagonist shifts its helix 12 to a repressed form which allows the binding of a corepressor peptide [11]. By contrast, PPARα when bound with an agonist was shown to be in an active form that allows for the binding of a co-activator peptide [12]. As in the PPARγ crystal structures, the apo- and agonist-bound forms have been solved but an antagonist-bound form is not yet available. In the apo-form, PPARγ forms a homodimer, and the individual protomers adopt two distinct conformations: in one protomer, helix 12 is in an active position, while in the other protomer, helix 12 is shifted slightly [13]. The active protomer in the apo-form of PPARγ displayed few differences from the active form bound to BRL49653, a synthetic ligand [13–15]. In addition, PPARγ complexed with partial agonists, GW0072 and AZ242, showed structures similar to the apo-form described above [16,17]. As PPARγ apparently does not undergo a drastic conformational change as shown in the crystal structures, another view of PPARγ activation has been provided from studies using NMR spectroscopy and fluorescence anisotropy [18,19]. In this model, the PPARγ LBD displays its dynamic nature, and ligand-binding stabilizes the receptor in a certain conformation. These structural studies have basically compared two states of the receptor when in the steady state. However, the precise dynamic events that occur during the ligand-binding and receptor-activation processes are unknown.

We previously reported that several oxidized fatty acids, which commonly have an α,β-unsaturated ketone as a core structural moiety, bind covalently to a cysteine residue in the PPARγ LBD, and that this covalent binding was required for PPARγ activation by these ligands [20]. The irreversible binding of the ligands may help the low-affinity ligands to exert their activities by a cumulative effect, even when the ligand concentrations are not high. On the other hand, the chemical reactions and/or structural changes of the ligands associated with covalent binding may have a passive role in the PPARγ activation process. In the present study, we thoroughly investigated the functional significance of the covalent-binding of the ligands. To capture the events occurring in the ligand-binding processes, we constructed a novel stopped-flow absorption spectrophotometric system with improvements to decrease photo-bleaching of the ligand. Using this system, we observed a two-step reaction that employed a ‘dock and lock’ mechanism of ligand binding, in which 15d-PGJ2 first enters into the ligand-binding pocket (dock), and then the covalent binding of the ligand occurs at a relatively low rate (lock). Mutation analyses revealed that the first (docking) step, from the free to the non-covalently bound form, was not sufficient to activate PPARγ, but the second (locking) step, from the non-covalent to the covalent bound form, was the critical step for activation.

EXPERIMENTAL

Chemicals

15d-PGJ2 was obtained from CAYMAN Chemical Co. All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich Japan or Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd.

Protein preparation

The His-tagged PPARγ LBD (aa 195–477) was expressed and purified from Escherichia coli as described previously [20]. We omitted the reducing agent from all buffers. The C285S mutation was introduced into pET28-PPARγ as described previously [20].

Steady state spectroscopic measurements

15d-PGJ2 was mixed with the PPARγ LBD for 20 min and the UV spectrum was measured with a DU640 spectrophotometer (Beckman).

Stopped-flow system for spectroscopic recording

To protect the ligand from photo-bleaching, we developed a system for spectroscopic recording with a stopped-flow apparatus (Figure 1A). The system consists of a stopped-flow apparatus and a spectrometer, RSP-1000 (UNISOKU, Co. Ltd.), a pulse generator, DG535 (Stanford Research Systems, Inc. CA, U.S.A.), a high-speed shutter, LS6T2 and its controller, VMM-D3 (Vincent Associates, NY, U.S.A.).

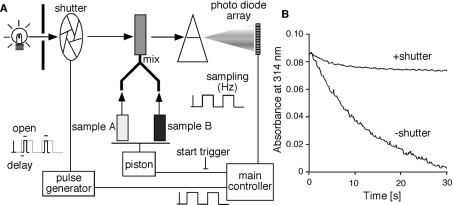

Figure 1. Schematic drawing of the experimental apparatus used in this study.

(A) The main controller generates a start trigger, by which the two samples are immediately mixed. The main controller also generates pulses for sampling signals from the photo-diode array. The same pulses are transmitted to a pulse generator, which controls a shutter. The pulse generator is triggered by the onset of each pulse, and generates pulses with a specific delay and on-time. The shutter opens during the on-time of each pulse. By this system, the light exposure of the samples is minimized, and the photo-bleaching of the samples can be prevented. (B) Monochromatic traces at 314 nm were recorded with (+shutter) or without (−shutter) the shutter. 15d-PGJ2 (10 μM) and 59 μM PPARγ LBD protein were mixed at a 1:1 ratio and then spectra were recorded. To simplify the traces, absorbance of 15d-PGJ2 at 314 nm only is shown.

Multi-wavelength global fitting of spectral kinetics by SPECTRAC

The one-step reaction model (A+B→D) was defined as follows,

|

where NR and NR:ligand refer to a nuclear receptor and a ligand-conjugated nuclear receptor respectively. The initial concentrations of NR and a ligand are defined as [NR]=A0, [ligand]=B0. The concentrations of NR, a ligand and NR:ligand at a certain time point are defined as [NR]=A(t), [ligand]=B(t) and [NR:ligand]=D(t) respectively. The reaction speed is described by the equation:

|

(1) |

A(t) and B(t) are calculated as A0−D(t) and B0−D(t), respectively. Then equation (1) can be converted to:

|

(2) |

If A0 is equal to B0, then (2) can be solved in terms of D(t):

|

(3) |

If A0 is not equal to B0, then (2) can be solved in terms of D(t):

|

(4) |

In addition, the absorbance observed (Obs) at a certain wavelength (λ) at certain time point (t) can be defined by the following:

|

(5) |

where ϵA(λ), ϵB(λ), and ϵD(λ) represent the molar absorption coefficients of each molecule. We obtained the k value, ϵA(λ), ϵB(λ), and ϵD(λ) after nonlinear least-square fittings of the data using equations (3), (4) and (5) by quasi-Newton methods. The two-step reaction model (A+B↔C→D) is defined as follows:

|

where NR/ligand means a non-covalent complex between a nuclear receptor and a ligand. The initial concentrations of NR and ligand are defined as [NR]=A0, [ligand]=B0. The concentrations of NR, ligand, NR/ligand and NR:ligand at a certain time point are defined as [NR]=A(t), [ligand]=B(t), [NR/ligand]=C(t), and [NR:ligand]=D(t), respectively. Assuming a rapid equilibrium, the reaction speed is described by the following equation:

|

(6) |

Here, A(t) and B(t) are obtained by A0−C(t)−D(t) and B0−C(t)−D(t), respectively. Then, equation (6) can be changed to:

|

(7) |

Equation (7) can be changed to:

|

(8) |

Equation (8) can be solved in terms of C(t):

|

(9) |

The rate of the production of [NR:ligand] can be expressed by the following equation:

|

(10) |

The differential equation in terms of the rate of the production of D(t) can be obtained from equations (9) and (10). Here, D(0)=0. Then, the differential equation can be solved by the Runge–Kutta method. C(t) is obtained from equation (9), using the obtained D(t). A(t) and B(t) are calculated by A0−C(t)−D(t) and B0−C(t)−D(t) respectively. In addition, the absorbance observed at a certain wavelength (λ) at a certain time point (t) can be defined by following equation:

|

(11) |

Then, we obtain the Ka, k, ϵA(λ), ϵB(λ), ϵC(λ), and ϵD(λ) values after nonlinear least-squares fitting of the data by quasi-Newton methods.

Trypsin sensitivity assay

Purified PPARγ proteins (typically 0.1 μg/10 μl of reaction volume) were incubated with 10 μM ligands for 20 min at room temperature. Then 30 ng of trypsin was added to the reaction. Every 10 min, an aliquot of the reaction mixture was removed, and the reaction was stopped by adding SDS/PAGE sample buffer, and boiling. Samples were separated by SDS/PAGE and visualized by silver staining. The residual PPARγ proteins were quantified using NIH (National Institutes of Health) Image software version 1.63.

Cell culture and luciferase assay

Cell culture, transient transfection and luciferase assay were described previously [20]. Notably, we used a GAL4 DNA-binding domain (DBD)-fused PPARγ LBD as a model system of PPARγ activation by ligand binding.

RESULTS

Overview of the spectroscopic recording system

When we recorded the spectrum of 15d-PGJ2 using a conventional stopped-flow system, we encountered the problem that 15d-PGJ2 was photo-bleached during recording (Figure 1B). This occurred because the sample was continuously exposed to light even when a spectrum was not being recorded. Therefore we developed an improved system, in which the light was exposed to the sample only when the spectrum was being recorded (Figure 1A). The main controller generates a start trigger and sampling pulses, and thus the system is basically the same as a conventional stopped-flow apparatus. The major difference is the manipulation of the light-exposure time and the sampling time. Using a pulse generator, a high-speed shutter placed between the light source and the sample cuvette was opened with a specific time-delay relative to the onset of each sampling pulse. The sampling time in this system was determined by the opening time of the shutter, and thus the total light exposure was greatly decreased. Using this system, we have successfully prevented the sample photo-bleaching (Figure 1B).

Monochromatic analysis of the binding kinetics

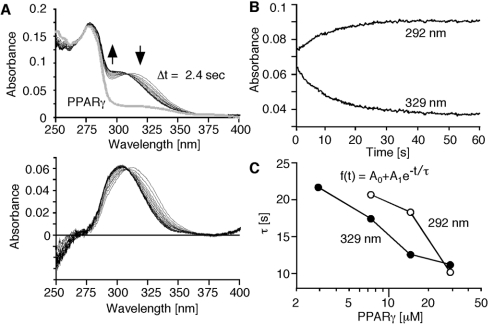

We analysed the binding kinetics using monochromatic traces extracted from the spectra. By mixing 15d-PGJ2 (final concentration 5 μM) with the PPARγ LBD (final concentration 29.5 μM), spectra were measured every 1.2 s, and the spectra at every 2.4 s were superimposed (Figure 2A, upper panel, black lines). The spectrum of PPARγ without 15d-PGJ2 was also recorded at a single time-point (Figure 2A, upper panel, thick grey line). The PPARγ spectrum was subtracted from all spectra (Figure 2A, lower panel). The peak absorbance of 15d-PGJ2 was shifted from 320 to 300 nm. Maximum upward and downward shifts of the spectra were observed at 329 and 292 nm respectively (Figure 2A, arrows). Time-dependent changes at 329 and 292 nm were fit by the single exponential equation, represented as f(t)=A0+A1e−t/τ, where f is absorbance, A0 is the value at t=0, A1 is the magnitude of the change, and τ is the relaxation time of the change. We calculated the relaxation times with four different concentrations of PPARγ (Figure 2C), which showed the concentration dependence at each wavelength. However, the relaxation time obtained at 292 nm was significantly larger than that at 329 nm, indicating that the reaction was not a simple two-state transition. Using 2.9 μM PPARγ, the change in the signal was minimal, and the signal-to-noise ratio decreased. As a result, we only observed the decrease in the 329 nm peak, and did not observe the appearance of the 292 nm peak. Therefore we proposed that this ligand-binding reaction is mediated by an intermediate state.

Figure 2. Time-dependent changes of spectra and monochromatic analysis of the binding kinetics.

(A) Spectral changes of 15d-PGJ2 after mixing with the PPARγ LBD. Arrows indicate the spectral changes of the mixture (upper panel). Traces at every 2.4 s are shown. A spectrum of PPARγ alone is also superimposed (upper panel, thick grey line) on to the trace. Net spectral changes of 15d-PGJ2 were obtained by subtracting the spectrum of PPARγ LBD from all spectra of the mixture (lower panel). Peak absorbance of 15d-PGJ2 was shifted from 320 to 300 nm. Maximum change was observed at 292 and 329 nm. (B) Time course of absorbance changes at 292 and 329 nm which showed maximum changes. (C) Concentration dependency of relaxation time at 292 and 329 nm. The traces at 292 and 329 nm were fitted to a single exponential equation, f(t)=A0+A1e−t/τ (inset). A0 is the value at t=0, A1 means the magnitude of a change, and τ is the relaxation time of a change. The values of τ obtained with four different concentrations of PPARγ LBD are plotted. The concentration of 15d-PGJ2 is fixed at 5 μM.

Multi-wavelength global fitting analysis of the stopped-flow spectroscopy data

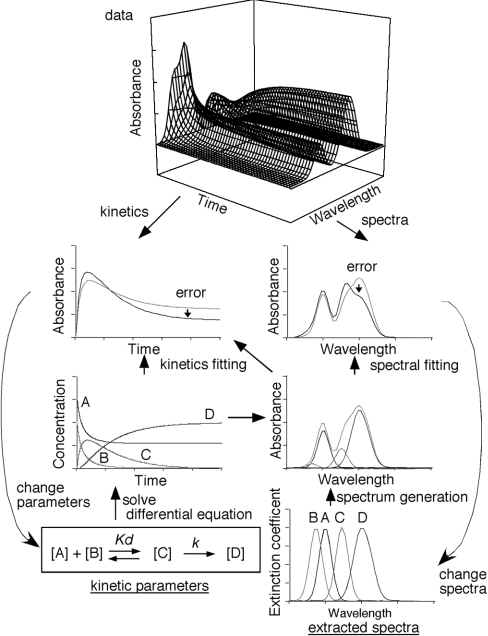

Since we lacked any information about the spectrum of the intermediate form, we developed an analysis tool (named SPECTRAC, spectral extractor) to obtain the spectra and the binding constants by analysing multi-wavelength kinetics (Figure 3). Once the chemical reaction and the initial sample concentrations are defined, SPECTRAC simulates the expected concentration changes by solving the differential equation based on the chemical reaction. In this analysis, the binding constant of the reaction and spectra for 15d-PGJ2, PPARγ and the product are arbitrary at the beginning. Using the calculated concentrations and the spectra of the molecules, SPECTRAC generates the spectral changes. Then the binding-constant of the reaction and the spectra for 15d-PGJ2, PPARγ and the complexes are improved by nonlinear least-squares fitting of the real data with the calculated data. When we defined a one-step reaction model, in which 15d-PGJ2 enters the PPARγ ligand-binding pocket and simultaneously reacts with the cysteine residue of the PPARγ LBD, we obtained spectra of PPARγ, 15d-PGJ2, and the covalently bound 15d-PGJ2–PPARγ complex similar to those observed in the steady state experiments (results not shown). The rate constant (1.6×103 s−1·M−1) of the reaction calculated by SPECTRAC was similar to that calculated from the blocking rate (7.9×102 s−1·M−1) of the free cysteine residue in the PPARγ LBD, detected by rhodamine-maleimide reactivity using the same reaction model [20]. These two assays, assessing the modification of either the ligand or the receptor, yielded similar reaction-rate constants, indicating the accuracy of this analysis.

Figure 3. Schematic drawing of kinetics and the SPECTRAC method.

The stopped-flow data consist of kinetic and spectral information, which are both simultaneously analysed by SPECTRAC. Before starting the analysis, the chemical reaction must be defined (lower left), in which the initial binding constant and each spectrum can be arbitrary (bottom left and right graphs). Initial concentrations of samples ([A] and [B]) must be defined. First, the differential equation based on the reaction kinetics is solved by the Lunge–Kutta method, which gives the concentration of each molecule at a certain time ([A], [B], [C] and [D] in the third left graph). Using the obtained concentration and spectra of each molecule, the expected spectrum at a specific time can be calculated (third right graph). At the same time, the expected kinetics curve can be calculated (grey line in second left graph). Nonlinear least-squares fitting of the data with the spectra obtained by the above procedures improves the dissociation and rate constants (Kd and k) and each spectrum. At the end, kinetic parameters and extracted spectra can be obtained. The error is represented as the root mean square deviation (R.M.S.D.) of the entire spectra.

Details of the ligand-binding kinetics

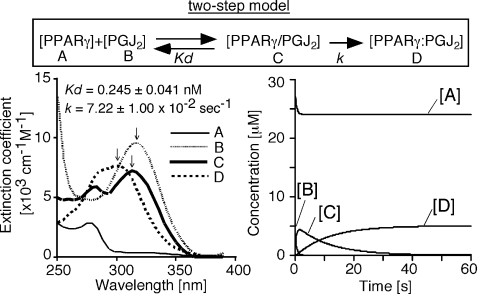

We defined a two-step reaction model, in which 15d-PGJ2 first binds non-covalently to PPARγ, and then a Michael addition produces the final complex (Figure 4, upper panel). The spectrum and the concentration change of each molecule were extracted from 60 s duration data analysis by SPECTRAC (Figure 4). We used molar absorption coefficients to represent the spectrum of each molecule, because a spectrum shown as absorbance changes depending on a time. The extracted spectra revealed that the peak absorbance of 15d-PGJ2 at 320 nm (Figure 4; lower left panel, line B) was first reduced and shifted slightly to a shorter wavelength at 315 nm (Figure 4; lower left panel, line C), and then it shifted to the final peak at 300 nm (Figure 4; lower left panel, line D). The concentrations of each molecule represent the rapid transition of the first step, followed by the slow covalent-binding step (Figure 4, lower right panel). Using the data from four independent experiments with various PPARγ concentrations, we calculated the Kd and k values as 0.245±0.041 nM and (7.22±1.00)×102 s−1 (mean±S.E.M. for n=5) respectively. Although we hypothesized that the first step would achieve equilibrium rapidly, the dissociation rate at a very early stage tends to be underestimated, because a vast empty pocket is available for ligand binding without displacement. As a result, the apparent dissociation constant may be low.

Figure 4. Spectral analysis of the binding kinetics by multi-wavelength global fitting, based on a two-step model.

An example of the result of SPECTRAC analysis of 15d-PGJ2 binding kinetics to PPARγ LBD. The chemical reaction is represented as A+B↔C→D, where the dissociation constant of the first step is Kd, and the rate constant of the second step is k. In this figure, PGJ2 indicates 15d-PGJ2. PPARγ/PGJ2 means PPARγ LBD non-covalently bound by 15d-PGJ2. We used molar absorption coefficients to represent the spectrum of each molecule, because the spectrum shown as absorbance changes depending on a time. The spectra of 15d-PGJ2, PPARγ/PGJ2 and PPARγ:PGJ2 are indicated by dashed line (line B, peak absorbance at 320 nm), thick line (line C, peak absorbance at 315 nm), and dotted line (line D, peak absorbance at 300 nm), respectively. The dissociation constant (Kd) of the first step, 0.245±0.041 nM, and the rate constant (k) of the second step, 7.22×102 s−1, were calculated from five independent experiments. The root mean square deviation (R.M.S.D.) of the entire spectra was 0.001377 in this example.

The intermediate state is stalled in a C285S PPARγ mutant

To confirm that the intermediate state was actually derived from the non-covalently bound PPARγ–15d-PGJ2 complex, we used a C285S PPARγ mutant that showed no activation by 15d-PGJ2 in cells [20]. The steady-state absorbance spectrum of 15d-PGJ2 in the absence or in the presence of WT (wild-type) or C285S protein was recorded for 30 min after mixing. 15d-PGJ2 alone showed a peak absorbance at 320 nm (Figure 5A, fine dashed line). By mixing it with the WT PPARγ, the spectrum of 15d-PGJ2 displayed a blue-shifted peak absorbance at 300 nm in the steady state reaction (Figure 5A, dashed line). By contrast, 15d-PGJ2 mixed with the recombinant C285S PPARγ protein showed a smaller blue-shift in the peak absorbance at 315 nm (Figure 5A, thick line). The shifted peak absorbance of 15d-PGJ2 on addition of the C285S mutant was similar to that observed for the intermediate state in the WT stopped-flow experiment (Figure 4, line C). To confirm that 15d-PGJ2 actually binds to the C285S mutant, we next measured the dissociation constant of 15d-PGJ2 bound to the C285S mutant in the steady state. To separate the spectra derived from the bound and free 15d-PGJ2, we used SPECTRAC without a kinetic analysis, in which the dissociation constant (Kd) and the spectra of PPARγ and of bound and free 15d-PGJ2 were calculated by nonlinear least-squares fitting with the data (Figure 3, right-panel). Increasing the amounts of the proteins produced more 15d-PGJ2–PPARγ complexes in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 5B). The Kd value obtained from this steady-state experiment using the C285S mutant was 3.05±0.21 μM (n=5).

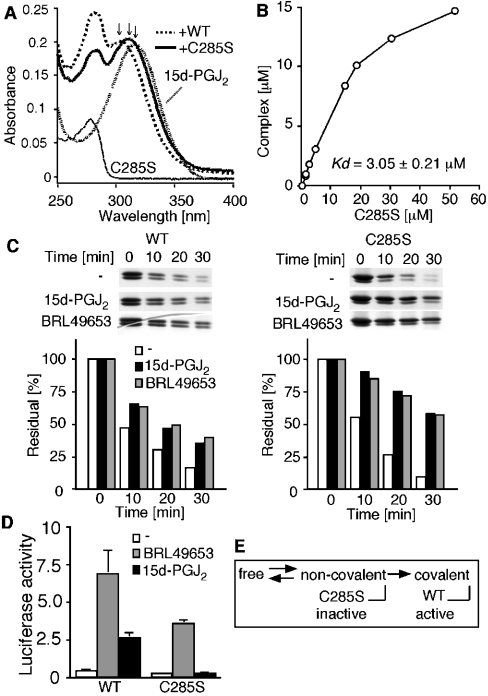

Figure 5. Capturing the intermediate state of the C285S PPARγ mutant.

(A) Spectral changes of 15d-PGJ2 in the presence of the WT or C285S mutant PPARγ LBD. The spectra represent 20 μM C285S protein (thin line), 10 μM 15d-PGJ2 (fine dashed line), the mixture of 10 μM 15d-PGJ2 and 25 μM WT protein (dashed line), and the mixture of 10 μM 15d-PGJ2 and 20 μM C285S protein (thick line). Arrows indicate the peak absorbance of 15d-PGJ2 alone (320 nm), 15d-PGJ2 after mixing with the C285S protein (315 nm) and 15d-PGJ2 mixed with the WT protein (300 nm). (B) Dose-dependent formation of the 15d-PGJ2–C285S complex. Different amounts of the C285S protein were incubated with 15 μM 15d-PGJ2, and the concentration of the complex was calculated by SPECTRAC. A Kd value of 3.05±0.21 μM was obtained (n=5). (C) Ligand-induced partial resistance to trypsin digestion in the WT and C285S proteins (left and right panels respectively). The WT and C285S proteins were incubated with or without indicated ligands (10 μM) and then digested with trypsin. At the indicated time points, the reaction was terminated and the residual proteins were visualized by silver staining. The density of the residual protein was quantified and plotted as the percentage of the undigested protein. (D) Activity of WT and C285S mutant in culture cells. COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with the reporter vector (pUASG-luc), internal control vector (pEYFP-N1) and the GAL4 DBD-fused PPARγ LBD vector. After transfection, cells were treated with indicated ligands (10 μM), and 24 h later, luciferase activity was determined. Yellow fluorescent protein was used as an internal control to calculate transfection efficiency. (E) Summary of the relationship between the binding kinetics and activity. 15d-PGJ2 first binds non-covalently to the PPARγ, and subsequently the Michael addition between them leads to the activation of PPARγ. By contrast, 15d-PGJ2 binds non-covalently to the C285S mutant, but the complex stays in the inactive intermediate state. Thus this covalent binding is a critical step for PPARγ activation by 15d-PGJ2.

Furthermore, to confirm that the spectral changes of 15d-PGJ2 observed above were not induced by a non-specific effect from the C285S mutant, we analysed the changes that occurred on the receptor in the presence of 15d-PGJ2. It is known that the LBDs of nuclear receptors undergo conformational and/or dynamic changes, resulting in a partial resistance to trypsin digestion [21]. When incubated with 15d-PGJ2 or BRL49653, the WT PPARγ protein indeed showed partial resistance to trypsin digestion (Figure 5C, left panel). In the C285S mutant, the resistance to trypsin digestion by ligand addition was more obvious (Figure 5C, right panel). In both the WT and C285S mutant, 15d-PGJ2 induced a similar effect on the receptor proteins in terms of trypsin sensitivity. This result indicates that 15d-PGJ2 binds to the C285S mutant. On the other hand, we showed that the C285S mutation totally abolished the activation of a GAL4 DBD-fused-PPARγ LBD by 15d-PGJ2 as determined by a culture cell system (Figure 5D). Then we concluded that the complex between the C285S mutant and 15d-PGJ2 corresponded to the intermediate state observed in the WT complex (Figure 5E).

DISCUSSION

To understand the role of covalent binding in the 15d-PGJ2-induced PPARγ activation, we analysed the relationship between binding kinetics and activity. In previous reports, the PPARγ antagonists, GW9662 and T0070907, and a PPARγ agonist, L-764406, were shown to bind covalently to the cysteine residue of the PPARγ LBD [22–24]. The cysteine residue is required for these compounds to bind to the receptor [23,24], suggesting that covalent bond formation helps these synthetic ligands to bind to the receptor. In a similar way, it is also conceivable that the covalent binding of 15d-PGJ2 may exert a cumulative effect through irreversible activation. On the other hand, we observed that 15d-PGJ2 can bind to the C285S PPARγ mutant non-covalently without receptor activation (Figure 5), indicating that covalent binding is required for the PPARγ activation, rather than for assisting in the ligand binding. We noticed that the Kd value of 15d-PGJ2 binding to the C285S mutant (Figure 5B) was similar to the EC50 of 15d-PGJ2 (2 μM) in PPARγ-mediated transcription assays using cultured cells [4,5]. The second covalent-binding step itself in WT PPARγ is a concentration-independent reaction; thus the EC50 may reflect the Kd value of the docking step. The reason why the synthetic ligands require the cysteine residue for ligand binding, whereas 15d-PGJ2 requires it for receptor activation rather than ligand binding, is currently unknown; however, it might be derived from the difference in their chemical reactions (the nucleophilic aromatic substitution of a chlorine versus the Michael addition reaction of an α,β-unsaturated ketone) or the difference in their resultant structures.

What is happening at the covalent-binding step? In addition to the static structural information from crystals, the dynamics of ligand binding to the PPARγ LBD have been determined by NMR [18] and fluorescent anisotropy using fluorescently-labelled PPARγ [19]. These studies basically measured the events that occurred on the receptor as a result of their ligands in a steady state, and represented another view of the receptor activation mechanism, in which a dynamic ensemble of conformations shift in response to ligand binding. On the other hand, we measured the spectral changes that occurred on the ligand after binding to the receptor, and revealed that the intermediate state, where 15d-PGJ2 associates with but does not bind covalently to the receptor, is inactive. As far as we know, this is the first presentation of an intermediate state in a nuclear-receptor–ligand interaction. Our data for the kinetics of the ligand complement the previous results regarding the structure and dynamics of the receptor. That is, the dynamic movement of the unbound receptor might allow the ligand to migrate into the deep ligand-binding pocket. When the ligand adapts to a certain conformation in the ligand-binding pocket, a Michael addition may occur. Then the covalent binding leads to receptor activation. It will be interesting in the future to determine whether covalent binding causes the receptor to change its conformation or fixes its dynamic movement.

It is tempting to speculate that a functional role for covalent binding is to decrease the signal-to-noise ratio in receptor activation. That is, the ligand-binding pocket of PPARγ is large enough to accommodate a variety of lipid metabolites with low specificities and affinities [25–27], and thus, PPARγ has many opportunities to encounter pseudo-ligands. To discriminate true ligands from the pseudo-ligands, PPARγ needs to recognize the difference between them. It is generally considered that ligand-receptor specificity is achieved by a ‘key and keyhole’ mechanism, involving a number of electrostatic contacts and hydrophobic interactions between them. In fact, synthetic PPARγ agonists seem to be rigid and to obtain their selectivity by their specific contacts with the receptor [12]. By contrast, lipid metabolites are quite flexible, and their positions in the large ligand-binding pocket cannot be fixed, as seen in the crystal structure of PPARδ LBD bound with eicosapentaenoic acid [25]. The ‘dock and lock’ mechanism proposed here may explain how PPARγ copes with the low selectivities and affinities of such flexible ligands.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Kosuke Morikawa and Mr Takuma Sugi for helpful comments and discussions. This work was supported by a research grant endorsed by the NEDO (New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization). The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Evans R. M., Barish G. D., Wang Y.-X. PPARs and the complex journey to obesity. Nat. Med. 2004;10:1–7. doi: 10.1038/nm1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Willson T. M., Lambert M. H., Kliewer S. A. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ and metabolic disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2001;70:341–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kliewer S. A., Lehmann J. M., Willson T. M. Orphan nuclear receptors: Shifting endocrinology into reverse. Science (Washington, D.C.) 1999;284:757–760. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forman B. M., Tontonoz P., Chen J., Brun R. P., Spiegelman B. M., Evans R. M. 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 is a ligand for the adipocyte determination factor PPARγ. Cell. 1995;83:803–812. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kliewer S. A., Lenhard J. M., Willson T. M., Patel I., Morris D. C., Lehmann J. M. A prostagrandin J2 metabolite binds peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ and promotes adipocyte differentiation. Cell. 1995;83:813–819. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagy L., Tontonoz P., Alvarez J. G. A., Chen H., Evans R. M. Oxidized LDL regulates macrophage gene expression through ligand activation of PPARγ. Cell. 1998;93:229–240. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McIntyre T. M., Pontsler A. V., Silva A. R., Hilaire A. S., Xu Y., Hinshaw J. C., Zimmerman G. A., Hama K., Aoki J., Arai H., Prestwich G. D. Identification of an intracellular receptor for lysophosphatidic acid (LPA): LPA is a transcellular PPARγ agonist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:131–136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0135855100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schopfer F. J., Lin Y., Baker P. R. S., Cui T., Garcia-Barrio M., Zhang J., Chen K., Chen Y. E., Freeman B. A. Nitrolinoleic acid: An endogenous peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor γ ligand. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:2340–2345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408384102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glass C. K., Rosenfeld M. G. The coregulator exchange in transcriptional functions of nuclear receptors. Genes Dev. 2000;14:121–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y., Lambert M. H., Xu H. E. Activation of nuclear receptors: A perspective from structural genomics. Structure. 2003;11:741–746. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu H. E., Stanley T. B., Montana V. G., Lambert M. H., Shearer B. G., Cobb J. E., McKee D. D., Galardi C. M., Plunket K. D., Nolte R. T., et al. Structural basis for antagonist-mediated recruitment of nuclear co-repressors by PPARα. Nature. 2002;415:813–817. doi: 10.1038/415813a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu H. E., Lambert M. H., Montana V. G., Plunket K. D., Moore L. B., Collins J. L., Oplinger J. A., Kliewer S. A., Gampe R. T., Jr, McKee D. D., et al. Structural determinants of ligand binding selectivity between the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:13919–13924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241410198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nolte R. T., Wisely G. B., Westin S., Cobb J. E., Lambert M. H., Kurokawa R., Rosenfeld M. G., Willson T. M., Glass C. K., Milburn M. V. Ligand binding and co-activator assembly of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ. Nature (London) 1998;395:137–143. doi: 10.1038/25931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uppenberg J., Svensson C., Jaki M., Bertilsson G., Jendeberg L., Berkenstam A. Crystal structure of the ligand binding domain of the human nuclear receptor PPARγ. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:31108–31112. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.47.31108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gampe R. T., Jr, Montana V. G., Lambert M. H., Miller A. B., Bledsoe R. K., Milburn M. V., Kliewer S. A., Willson T. M., Xu H. E. Asymmetry in the PPARγ/RXRα crystal structure reveals the molecular basis of heterodimerization among nuclear receptors. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:545–555. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80448-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oberfield J. L., Collins J. L., Holmes C. P., Goreham D. M., Cooper J. P., Cobb J. E., Lenhard J. M., Hull-Ryde E. A., Mohr C. P., Blanchard S. G., et al. A peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ ligand inhibits adipocyte differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:6102–6106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cronet P., Petersen J. F. W., Folmer R., Blomberg N., Sjoblom K., Karlsson U., Lindstedt E.-L., Bamberg K. Structure of the PPARα and -γ ligand binding domain in complex with AZ 242; ligand selectivity and agonist activation in the PPAR family. Structure. 2001;9:699–706. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00634-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson B. A., Wilson E. M., Li Y., Moller D. E., Smith R. G., Zhou G. Ligand-induced stabilization of PPARγ monitored by NMR spectroscopy: Implications for nuclear receptor activation. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;298:187–194. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kallenberger B. C., Love J. D., Chatterjee V. K. K., Schwabe J. W. R. A dynamic mechanism of nuclear receptor activation and its perturbation in a human disease. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003;10:136–140. doi: 10.1038/nsb892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shiraki T., Kamiya N., Shiki S., Kodama T. S., Jingami H. α,β-unsaturated ketone is a core moiety of natural ligands for covalent binding to peroxisome proliferaor-activated receptor γ. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:14145–14153. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500901200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamrazi A., Carlson K. E., Katzenellenbogen J. A. Molecular sensors of estrogen receptor conformations and dynamics. Mol. Endocrinol. 2003;17:2593–2603. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leesnitzer L. M., Parks D. J., Bledsoe R. K., Cobb J. E., Collins J. L., Consler T. G., Davis R. G., Hull-Ryde E. A., Lenhard J. M., Patel L., et al. Functional consequence of cysteine modification in the ligand binding sites of peroxisome proliferator activated recetpors by GW9662. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6640–6650. doi: 10.1021/bi0159581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee G., Elwood F., McNally J., Weiszmann J., Lindstrom M., Amaral K., Nakamura M., Miao S., Cao P., Learned R. M., et al. T0070907, a selective ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, functions as an antagonist of biochemical and cellular activities. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:19649–19657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200743200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elbrecht A., Chen Y., Adams A., Berger J., Griffin P., Klatt T., Zhang B., Menke J., Zhou G., Smith R. G., Moller D. E. L-764406 is a partial agonist of human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:7913–7922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.7913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu E. H., Lambert M. H., Montana V. G., Parks D. J., Blanchard S. G., Brown P. J., Sternbach D. D., Lehmann J. M., Wisely G. B., Willson T. M., et al. Molecular recognition of fatty acids by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Mol. Cell. 1999;3:397–403. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80467-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krey G., Braissant O., L'Horset F., Kalkhoven E., Perroud M., Parker M. G., Wahli W. Fatty acids, eicosanoids, and hypolipidemic agents identified as ligands of peroxisome proliferators-activated receptors by coactivator-dependent receptor ligand assay. Mol. Endocrinol. 1997;11:779–791. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.6.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kliewer S. A., Sundseth S. S., Jones S. A., Brown P. J., Wisely G. B., Koble C. S., Devchand P., Wahli W., Willson T. M., Lenhard J. M., Lehmann J. M. Fatty acids and eicosanoids regulate gene expression through direct interactions with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α and γ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:4318–4323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]