Abstract

Foamy virus (FV) vectors that have minimal cis-acting sequences and are devoid of residual viral gene expression were constructed and analyzed by using a packaging system based on transient cotransfection of vector and different packaging plasmids. Previous studies indicated (i) that FV gag gene expression requires the presence of the R region of the long terminal repeat and (ii) that RNA from packaging constructs is efficiently incorporated into vector particles. Mutants with changes in major 5′ splice donor (SD) site located in the R region identified this sequence element as responsible for regulating gag gene expression by an unidentified mechanism. Replacement of the FV 5′ SD with heterologous splice sites enabled expression of the gag and pol genes. The incorporation of nonvector RNA into vector particles could be reduced to barely detectable levels with constructs in which the human immunodeficiency virus 5′ SD or an unrelated intron sequence was substituted for the FV 5′ untranslated region and in which gag expression and pol expression were separated on two different plasmids. By this strategy, efficient vector transfer was achieved with constructs that have minimal genetic overlap.

There is increasing interest in gene transfer using vectors derived from foamy viruses (FVs) (19, 43). In particular, their nonpathogenic nature, even in cases of accidental human infection, is a major feature that makes FVs attractive candidates for the development of a retroviral vector system (26). Such systems consist of two components, (i) the vector proper, harboring in cis the genetic elements required for RNA (pre-)genome dimerization and packaging, reverse transcription, provirus integration, and transgene expression, and (ii) a packaging cell line supplying the viral Gag, Pol, and Env proteins in trans (27, 28). However, since the replication strategy of FVs differs from the conventional replication pathway common to all non-FV retroviruses (orthoretroviruses) (24) and is still poorly characterized, FV vector development is in its infancy.

In previous studies, two cis-acting sequences (CASI and CASII) have been identified that are required for transfer of FV vectors (8, 14, 45). A further sequence element located in the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) was found to be essential for expression and processing of the Gag and Pol proteins (15, 35). The situation is further complicated by the fact that vector particles that were produced from constructs with large deletions in the 5′ UTR packaged as much pregenomic RNA as did constructs without deletions (15). Although the practical consequences as far as safety issues and vector titers are concerned may be minor or even nonexistent in the FV system, expression of the Gag and Pol proteins independently of RNA packaging would allow better characterization of FV capsid assembly and Pol incorporation.

Therefore, we set out to improve current FV vectors and packaging systems. To do this, we used derivatives of the virus isolate previously called human FV. Large-scale surveys did not identify natural human FVs (2, 41), and the sequencing of a chimpanzee virus demonstrated that the two isolates are almost identical (17). Thus, the so-called human FV likely represents a chimpanzee virus accidentally transmitted to a human (16, 40). Since the true origin of this reference virus will probably never be disclosed (1), we designated this isolate primate FV type 1 (PFV-1).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

Human fibrosarcoma (HT1080) and 293T (5) cells were cultivated in Eagle's minimal essential medium or in Dulbecco's modified minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and antibiotics.

Recombinant DNA.

All of the FV constructs used in this study are based on infectious PFV-1 molecular clone pHSRV2 (39). PFV-1 sequence positions are given with respect to the start of transcription (position 1 corresponds to the first nucleotide of the R region of the 5′ long terminal repeat [LTR]). All constructs were made by established molecular cloning techniques (3, 36). All point mutations generated by recombinant PCR (18) were verified by automated DNA sequence analysis of amplimers using AmpliTaqFS and the ABI 310 sequence analysis system (Perkin-Elmer). Other recombinant clones were characterized by multiple restriction enzyme digestions.

(i) Vector constructs.

The pMD9 vector was derived from pMH25 (14). It harbors a human cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate-early gene enhancer/promoter, the 5′ PFV-1 sequences up to nucleotide (nt) 645 (covering CASI), 3′ pol sequences from nt 3871 to nt 5885 (covering CASII), an enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) expression cassette under control of the spleen focus-forming virus U3 promoter downstream of CASII, the polypurine tract (ppt), and the 3′ LTR. The initiation sequence of the gag gene in pMD9 was changed from ATG GCT TCA to CTG GCT TAA (mutated nucleotides are in boldface) by recombinant PCR, and the 3′ U3 region from nt 10262 to nt 10820 was deleted. Note that this internal 558-bp U3 deletion from the BstEII site to the XbaI site in the HSRV2 LTR comes to a 1,204-bp deletion compared with the wild-type PFV-1 U3 region, since the HSRV2 U3 region is already a deletion variant (37). The vector pMD11 deviates from pMD9 in that the egfp marker gene was replaced with a lacZ marker with a nuclear localization signal (nlsLacZ) derived from the SFG NLS-lacZ retroviral vector (34). The vectors pMD12 and pMD15 are equivalent to pMD9 and MD11, respectively, but the marker gene cassettes were placed between CASI and CASII. The vector pMH32 has already been described (14).

(ii) Packaging constructs.

Expression of all packaging constructs is under the transcriptional control of the CMV enhancer/promoter. Plasmids pCgp-1 (no deletion in the 5′ UTR) and pCgp-10 (with a deletion in the 5′ UTR from position 151 to position 444), both directing expression of the PFV-1 Gag and Pol proteins; pCgp-8 (with a deletion in the 5′ UTR from position 10 to position 345), which fails to express the Gag and Pol proteins; and pCpol-2 and pCenv-1, which direct expression of the Pol and Env proteins, respectively, have been described previously (11, 14, 15). In pCgp-14, the PFV-1 major 5′ SD sequence (underlined) was changed from 5′-GGTTTGGTAAG-3′ to 5′-GGTTTGGGAAG-3′ by recombinant PCR on a 0.41-kb NdeI/SspI fragment. In a similar fashion, the sequence just upstream of the SD site was changed to 5′-GATTTGGTAAG-3′ in pCgp-15. Plasmid pCZgag-2 was obtained by inserting the PFV-1 gag sequences from the ATG start codon up to a HincII site at position 2617, which is located in the pol gene, into the pcDNA3.1zeo+ expression vector (Invitrogen). In addition, this plasmid contains the M54 mutation inactivating the pol ATG start codon (7). In pCZgp-1, the gag/pol coding sequences from the gag ATG start codon up to the EcoRV site at position 5884 located in env were inserted into pcDNA3.1zeo+. Plasmids pCIgag-2 and pCIgp-2 harbor the gag and gag/pol sequences, respectively, which were inserted downstream of the chimeric β-globin-immunoglobulin G (IgG) intron of the pCI expression vector (Promega). The pCZI expression vector was generated by inserting the CMV enhancer/promoter and CMV intron A, excised as a 2.35-kb EcoRI fragment from plasmid pHit60 (42), via blunt-end ligation into MfeI/NheI-cut pcDNA3.1zeo+. pCZIgag-2 and pCZIgp-2 were derived by inserting the PFV-1 gag and gag/pol sequences, respectively, into pCZI. In pCZgag-5 and pCZgp-5, two self-annealed oligonucleotides, representing the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) molecular clone HXB2 sequence from nt 728 to nt 773 (GenBank accession number K03455), were inserted between the CMV promoter and the PFV-1 gag and gag/pol genes. This insertion corresponds to the sequence from position 274 to position 319 after the HIV-1 start of transcription, and therefore, the major 5′ SD at position 289 is contained (30). pCZgag-6 and pCZgp-6 were derived by insertion of PCR-amplified murine leukemia virus (MuLV) SFG vector (34) sequences from nt 1 to nt 616 (GenBank accession number J02255) into the PFV-1 gag and gag/pol expression plasmids to replace the PFV-1 leader. In these plasmids, the PFV-1 gag ATG is in the same position relative to the start of transcription as the original MuLV gag ATG. The CTG used to initiate translation of glycosylated MuLV Gag is still present in this construct (32). However, a stop codon was introduced 18 amino acids downstream of the CTG and, consequently, N-terminally elongated PFV-1 Gag was prevented. For the gag/pol-encoding gp plasmids, the respective pol ATG initiation codon mutations to CTG were obtained by exchange of a 1.83-kb SwaI/PacI fragment with the M54 mutant (7).

(iii) Vectors used to generate cRNA probes.

pSP/HFV-3 contains a 1.6-kbp NcoI/SacI fragment of pHSRV2 in plasmid pSP65 (Roche) (15). A gag gene-related in vitro antisense RNA transcript stretching from nt 1593 to nt 1258 was generated after linearization of pSP/HFV-3 with XbaI. pSP/HFV-4 contains nt 5551 to nt 5884 between the MscI and EcoRV sites of PFV-1 inserted in the antisense direction downstream of the SP6 promoter in pSP65. Following linearization with AflII, it was used to generate an in vitro RNA transcript stretching from nt 5884 to nt 5624 that covers the overlap of the pol and env genomic regions.

(iv) Bacterial expression of PFV-1 Gag protein.

The pET15b vector (Novagen) was modified to contain an SmaI restriction site in its polylinker by oligonucleotide insertion as previously described (20). In a subgenomic plasmid covering the gag open reading frame, the ATG initiation site was modified to contain an NdeI restriction site. pETgag was derived by inserting a 2.17-kb NdeI/HincII fragment ranging from the gag ATG to a HincII restriction site in pol into NdeI/SmaI-cut pET15b in frame to the N-terminal histidine tag.

DNA transfections and analysis of vector transfer efficiency.

All transfections were carried out by using a calcium phosphate cotransfection protocol essentially as previously described (14, 15), with up to 21 μg of plasmid DNA per 1.8 × 106 293T cells seeded in 6-cm-diameter dishes the day before. Vector transduction efficiencies were determined as previously described (14, 15), with slight modifications. Briefly, 48 h following transfection, 3 ml of cell-free supernatant (0.45 μM filtrate) was added to HT1080 recipient cells, which were seeded at a density of 104 per well in 12-well plates 1 day before transduction. The cells were monitored for EGFP expression 3 days after transduction by flow cytometry on a FACScan using the LysisII and CellQuest software packages (Becton Dickinson). Transduction efficiency was expressed as the percentage of EGFP-positive cells in relation to the total number of cells assayed (usually 104). To analyze the titer of LacZ-expressing vectors, the cell-free supernatants were serially diluted 10-fold and added to 104 HT1080 recipient cells seeded the day before. β-Galactosidase expression was assayed 2 days after transduction by counting blue cells under a light microscope following fixation with 0.5% glutaraldehyde and staining with freshly prepared staining solution (4 mM K-ferricyanide, 4 mM K-ferrocyanide, 2 mM MgCl2, 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside [X-Gal] at 0.4 mg/ml ) as described previously (39). All vector transfer experiments were done in quadruplicate with at least two independent preparations of plasmid DNAs.

Protein analysis and MAbs.

Lysates from transfected cells or from cell-free virus were prepared by resuspension in detergent-containing buffer (12, 14, 15). Cell-free virus from transfected cells was obtained by filtration of supernatant through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter (Schleicher & Schüll) and subsequent sedimentation through a 20% sucrose cushion in TNE (100 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) in an SW41 rotor (Beckman) at 25,000 rpm and 4°C for 3 h. The samples were subjected to electrophoresis through sodium dodecyl sulfate-containing 8% polyacrylamide gels and blotted semidry onto nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schüll). The blots were incubated with rabbit antisera raised against recombinant PFV-1 Gag (12) or with mouse monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) directed against the PFV-1 Gag and Pol proteins (20). The blots were developed with the ECL detection system (Amersham) after incubation with horseradish-coupled secondary antibodies directed against rabbit or mouse IgG (Dako).

Anti-Gag MAbs were generated from C57BL/6 mice infected with PFV-1 (38), boosted by infection with a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing PFV-1 Gag protein (10), and then boosted again with Gag protein expressed in and purified from bacteria to approximately 95% purity via nickel chelate chromatography as instructed by the supplier (Novagen). MAbs were generated essentially as described recently (20), and the supernatants of the hybridomas were screened by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with the bacterium-expressed, purified Gag protein. Following several subcloning steps, MAb SGG1 showed an almost background-free reaction in immunoblot and immunofluorescence assays and was used in this study.

RPAs.

All RNase protection analyses (RPAs) were performed with Direct Protect Detection kits from Ambion, essentially as described by the manufacturer. For detection of RNA in virions, virus was produced as described previously (14, 15). For detection of cellular RNA by RPA, total RNA was prepared 48 h following transfection with the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) and 5 μg of RNA was used per assay. In some experiments, extracted virion RNA was treated with 0.5 U of RQ1 DNase (Promega) at 37°C for 25 min. Antisense RNA probes were generated in vitro from XbaI-linearized pSP/HFV-3 and AflII-linearized pSP/HFV-4, respectively. RPAs of individual constructs were performed at least three times and quantitated with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

RESULTS

Improved PFV-1 vectors.

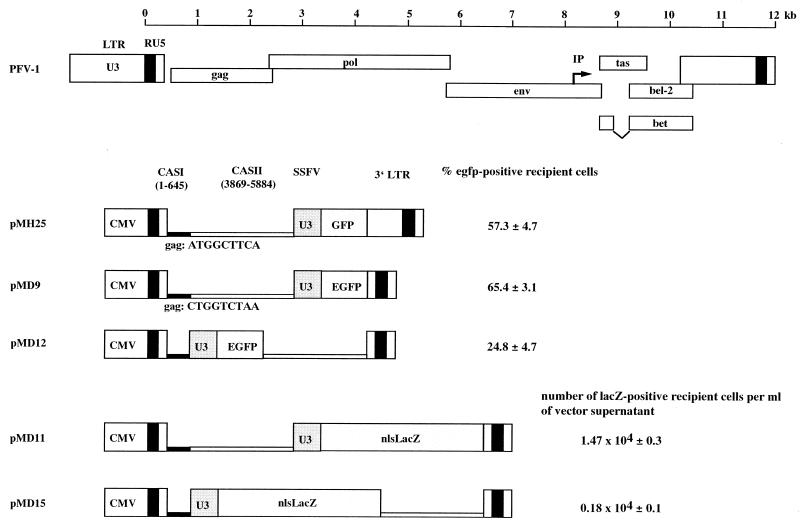

It has been demonstrated recently that, for efficient transfer, PFV vectors essentially require two genetic elements that are located in the 5′ UTR and extend into gag (CASI) and in the 3′ pol region (CASII) (14). Since a truncated Gag protein can be expressed from CASI-harboring vectors and dominantly interfere with Gag expressed from the packaging construct (14), we generated the pMD series of vectors, in which the Gag initiation sequence was down-mutated (Fig. 1). In addition, internal sequences were deleted from the 3′ U3 region of the LTR. FV gene expression depends on the presence of the viral Tas protein (33), which acts as a transcriptional trans activator via direct binding to proviral DNA in FV promoters (13, 22, 23). Although Tas is absent from most FV vectors, deletion of the Tas-responsive elements and the TATA box from the U3 promoter represents a further safety feature of the pMD vectors. Comparison of the vector transfer efficiency of pMD9 with that of the parental pMH25 vector revealed no decrease in the transduction rate of recipient cells that may have been caused by the introduced mutations (Fig. 1). To allow direct determination of vector titers, we constructed LacZ-expressing pMD11. As shown in Fig. 1, approximately 1.5 × 104 vector transducing units per ml of cell-free supernatant were obtained upon transient cotransfection of cells with vector, gag/pol (pCgp-1), and env (pCenv-1) expression plasmids under the assay conditions used.

FIG. 1.

PFV-1 proviral genome organization and new FV pMD vectors. The scale bar's left end corresponds to the start of transcription at the U3-R border. The pMH25 reference vector has been described previously (14). It harbors both of the cis-acting elements (CASI and CASII) required for vector transfer. The vectors contain an internal indicator gene cassette. Expression of an EGFP-encoding or nlsLacZ marker gene is directed by the spleen focus-forming virus U3 region. The cassette was inserted either downstream of CASII (pMH25, pMD9, and pMD11) or between CASI and CASII (pMD12 and pMD15). The percentage of EGFP-positive recipient HT1080 cells or the number of LacZ-positive recipient HT1080 cells obtained with supernatant from 293T cells after transient transfection with the vector genome, together with the pCgp-1 and pCenv-1 packaging constructs, is indicated. Mean values ± standard errors are shown. IP is the FV internal promoter (25).

The size of CASII and the relative location and size of the indicator gene cassette in FV vectors are matters of dispute (8, 14, 45). We therefore placed the indicator gene cassette between CASI and CASII and, in addition, created a variety of deletion mutants targeting CASII in either position. With EGFP as a marker, the introduction of the indicator gene cassette in place of the gag gene led to a greater than 50% reduction in marker gene-expressing recipient cells (Fig. 1). With LacZ as a marker, the reduction reached 90% (Fig. 1). Successive deletions of CASII between positions 4284 and 5624 in an egfp-transferring vector resulted in significant losses of transduction efficiency irrespective of whether egfp was placed up- or downstream of CASII (data not shown).

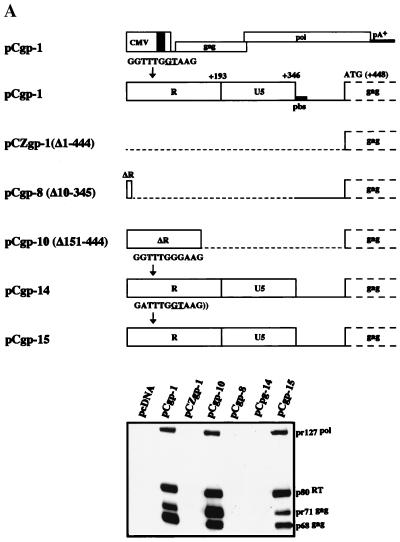

5′ PFV-1 gag expression constructs essentially require a 5′ splice donor sequence.

We previously showed that the PFV-1 5′ LTR R region is critical for expression of the Gag protein (15). Although the effect was described as mainly posttranscriptional, the mechanism of action remains obscure (35). The most prominent feature in the R region is the presence of the main 5′ SD at position +53 (15, 31). To get a better understanding on the regulation of PFV-1 Gag protein expression and to eventually minimize the 5′ UTR sequences needed in packaging constructs, we first generated a series of gag/pol expression constructs in which the 5′ SD sequence was mutated and analyzed them by immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 2A, a single point mutation of the 5′ SD site (pCgp-14; GT to GG) completely abrogated Gag protein expression while the mutation to AT of a GT motif 5 nt upstream of the SD site (in pCgp-15) did not at all alter the Gag protein expression level. Note that the lack of Pol protein expression in pCgp-14 is not surprising, since it is the consequence of the PFV-1 Pol protein being expressed from a spliced mRNA using the 5′ SD site (21, 46).

FIG. 2.

Analysis of the Gag and Pol protein expression levels of different FV packaging constructs. (A) Detail of the gag/pol expression constructs with either deletion or mutation of the 5′ leader sequence and analysis of Gag and Pol protein expression following transfection of 293T cells and immunoblotting with mouse anti-Gag and anti-Pol MAbs (20). pbs is the primer binding site. (B) Detail of gag/pol expression constructs with heterologous 5′ splice sites and analysis of Gag and Pol protein levels after transfection. (C) Vector transfer using packaging constructs with heterologous leader sequences. Determination of the abilities of different gag/pol expression constructs to transfer the pMD9 vector following cotransfection of 293T cells with pCenv-1 and transduction of HT1080 recipient cells. Mean values ± standard errors as, determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis, are shown.

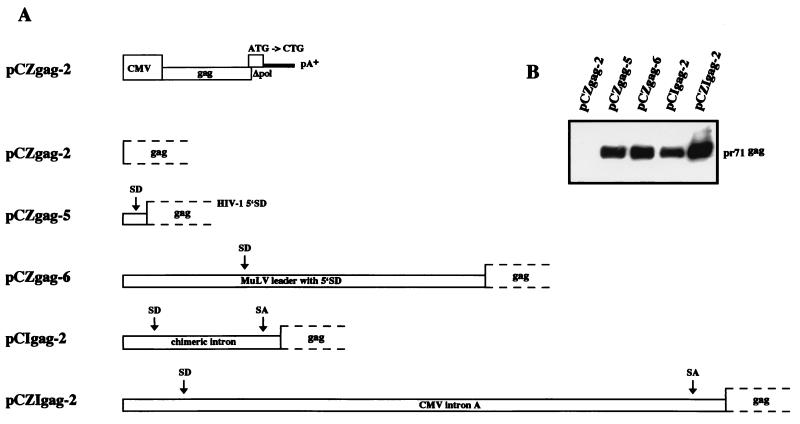

Replacement of the FV SD with heterologous splice sites.

We next asked whether an authentic PFV-1 5′ SD sequence has to be present in gag/pol expression constructs or whether it can be replaced with heterologous splice sites. To this end, plasmids pCZgp-5 and -6 containing the HIV-1 and MuLV major 5′ SD sequences, respectively, and plasmids pCIgp-2 and pCZIgp-2 harboring a chimeric β-globin IgG intron (pCIgp-2) and CMV intron A (pCZIgp-2), respectively, were analyzed for expression of the Gag and Pol proteins. As shown in Fig. 2B, the introduction of heterologous SD and splice acceptor (SA) sites or the introduction of only a heterologous SD site 5′ of the gag open reading frame restored PFV-1 Gag, as well as Pol, expression even in the absence of residual PFV-1 5′ UTR sequences. Note the weak intracellular presence of the cleaved p68 Gag protein in pCIgp-2-, pCZIgp-2-, pCZgp-5-, and pCZgp-6-transfected cells despite the expression of the pol-encoded protease, which is able to cleave the Pol precursor protein. This resulted from the absence in these expression constructs of a short U5 sequence, which has been found to be required for Gag cleavage (15). This cis-acting sequence is present in the parental pCgp-1 construct and can be supplied by the PFV-1 vector genome (15). Furthermore, it is noteworthy that expression of the Pol protein from the constructs harboring heterologous 5′ splice sites was detected regardless of whether additional SA sites were present in the constructs in addition to a 5′ SD site, i.e., complete heterologous intron sequences (Fig. 2B). Since expression of PFV-1 Pol proteins requires the generation of a spliced mRNA that uses an SA sequence in the gag gene (4, 21, 46), this implies the generation of a spliced mRNA from the heterologous 5′ SD to this FV SA site. To determine whether the presence of the FV pol SA site has any influence on Gag protein generation, we analyzed gag expression constructs harboring heterologous SD elements. We used constructs that have the pol mRNA SA and their M67 derivatives (21), which lack this SA site, and analyzed cell lysates for Gag protein by immunoblotting. The result revealed the independence of Gag protein generation from the presence of the pol SA (data not shown).

Analysis of vector transfer by using FV gag/pol packaging constructs with the 5′ UTR deleted.

The efficiency with which the newly established gag/pol packaging constructs incorporate the pMD9 vector was analyzed by triple transfection of 293T cells together with pCenv-1 and determination of transduction efficiency on HT1080 fibroblastoid cells. As shown in Fig. 2C, the abilities of the different packaging constructs to give rise to vector particles that transduce recipient cells correlated roughly with their protein expression levels observed in the previous experiment (Fig. 2B). Even with constructs pCZgp-6 and pCZIgp-2, which gave rise to the highest Gag levels and the best vector transfer rates, we obtained only 30 to 50% of the transduction rates achieved with the previously constructed packaging constructs containing wild-type PFV-1 5′ UTR sequences.

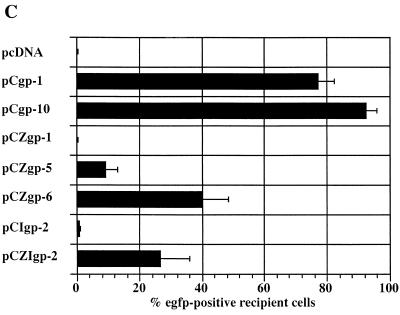

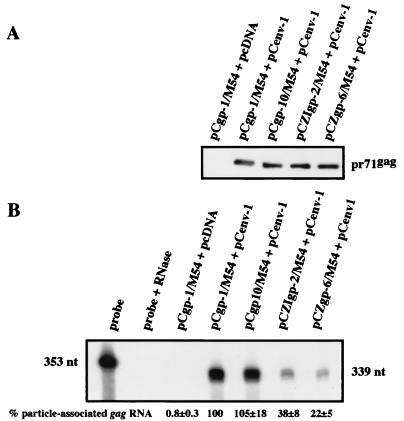

Packaging of RNA transcribed from gag/pol expression constructs.

To allow quantification of the RNA content of extracellular particles, thereby avoiding its degradation by particle-associated reverse transcription in the vector-producing cell (29), we used derivatives of the gag/pol-encoding packaging constructs in which the pol gene ATG was down-mutated to CTG. The packaging constructs were cotransfected with an env-expressing plasmid, and particles were prepared after centrifugation of the cell-free supernatant through a sucrose cushion. One-half of the particles were analyzed for the amount of Gag capsid protein by Western blotting (Fig. 3A). In parallel, RNA was extracted from the other half of the particle preparation and analyzed by RPA with a gag-derived probe (Fig. 3B). In these experiments, we specifically analyzed the packaging constructs pCZgp-6 and pCZIgp-2 (Fig. 3) because these yielded the best vector transfer among the newly created constructs. As expected, control experiments revealed that no viral particles were produced when pCgp-1/M54 was transfected in the absence of Env (11). Quantification of three independent RPAs revealed that the pCgp-1/M54 construct with the 5′ UTR not deleted, as well as the pCgp-10/M54 (Δ151-444) construct with the 5′ UTR partially deleted, gave rise to particles that package relatively large amounts of gag RNA (15). In contrast, both of the constructs with heterologous splice sites, pCZgp-6/M54 and pCZIgp-2/M54, showed approximately 80 and 60% reduced amounts of PFV-1 gag RNA, respectively (Fig. 3B). Still, packaging of some gag-related RNA was clearly detectable. Treatment of nucleic acids extracted from virions with DNase prior to RPA did not change the outcome of the experiment (data not shown), which indicated that potential contamination of the particles by transfected plasmid DNA was of no concern.

FIG. 3.

Determination of RNA incorporation from the gag/pol packaging constructs into FV vector particles. 293T cells were transfected with the M54 derivatives of the indicated gag/pol expression constructs together with an env expression plasmid. Viral particles were concentrated from cell-free supernatant by centrifugation through a sucrose cushion. Gag protein was detected by immunoblotting (A). Particles were analyzed for the gag RNA content derived from the packaging construct by RPA (B). Three independent RPAs were quantified by PhosphorImager analysis. The value obtained with reference plasmid pCgp-1/M54 was arbitrarily set to 100%, and means ± standard errors are shown for the other constructs (B).

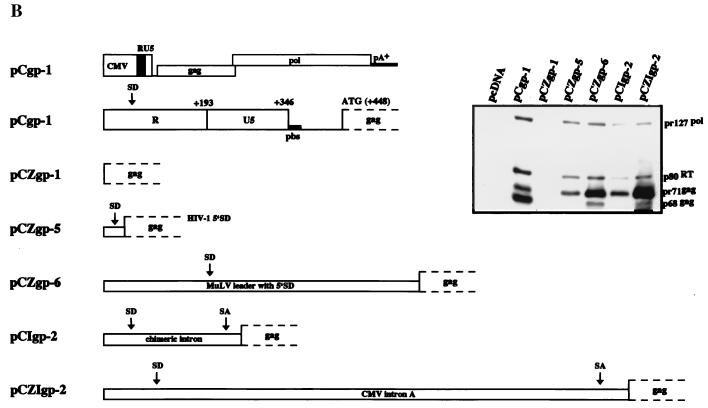

Analysis of vector transfer with separate Gag and Pol packaging plasmids.

We next separated the PFV-1 gag and pol expression constructs. To this aim, gag expression constructs with the FV 5′ UTR deleted were designed by inserting heterologous splice sites as described above. As depicted in Fig. 4, sole transfection of the four gag expression constructs in question gave rise to high levels of p71 Gag precursor protein. For analysis of vector transfer, we cotransfected 293T cells with the gag expression plasmids together with pCpol-2, pCenv-1, and the pMD9 vector. As shown in Fig. 4C, the vector transfer rate obtained with pCZgag-6 was similar to that obtained with the pCgp-1 reference packaging construct. In general, expression of the Gag and Pol proteins from two separate plasmids gave higher rates of transduction, likely due to higher protein production rates than those achieved by expression from a single plasmid that uses a non-PFV-1 5′ SD sequence to generate Gag and Pol (compare Fig. 2C and 4C, the results of which are from the same set of experiments). With separated gag and pol packaging constructs, titers in excess of 104/ml were achieved with lacZ-transducing vector pMD11 (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Analysis of the level of protein expression and the abilities of different gag expression constructs to package an FV vector. In panel A, the expression constructs used in this assay are shown in detail. Panel B shows a representative immunoblot analysis of Gag protein expression levels. In the experiment shown in panel C, 293T cells were cotransfected with the gag expression constructs, pCpol-2 and pCenv-1, and the vector pMD9, except for cells that were transfected with pCgp-1, pCenv-1, and pMD9. The efficiency with which the different gag expression constructs packaged the vector was determined by analyzing the transduction rate of EGFP marker-positive HT1080 recipient cells. The means ± standard errors of four independent experiments are shown.

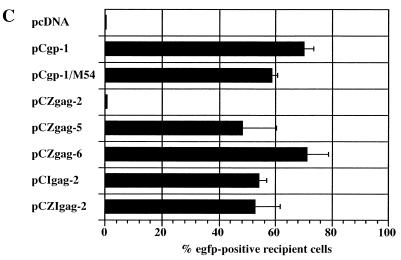

Packaging of RNA transcribed from Gag expression constructs.

We then analyzed the amount of packaging construct RNA in vector particles generated by cotransfection of cells with the Gag protein expression constructs and pCenv-1 by RPA (Fig. 5). Similar amounts of cell-free capsid proteins were prepared from all Gag expression constructs when cotransfected with an Env-expressing plasmid (Fig. 5A). In virions produced by cells cotransfected with pCgp-1/M54, which contains CASI and -II, and pCenv-1, gag RNA was prominent. In virions generated by cotransfection of pCenv-1 together with pCZgag-6 or pCZIgag-2, which both lack the 5′ part of CASI and all of CASII, the amount of particle-associated gag RNA was largely reduced but still detectable. Viral particles produced by cotransfection of pCIgag-2 or pCZgag-5 together with pCenv-1, however, contained barely visible amounts of gag RNA, as judged by RPA (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, quantification of three independent experiments by PhosphorImager analysis revealed a reduction of measurable radioactivity to less that 5%. The reduced levels of gag RNA packaged into particles generated with these expression constructs was not due to reduced intracellular RNA levels, which were comparable between the different constructs (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Determination of the amount of gag RNA incorporated into particles obtained after transfection of cells with different gag expression constructs. Approximately equal amounts of Gag protein (A), from particles that were obtained after cotransfection of 293T cells with individual packaging constructs and an env expression plasmid and purified by centrifugation through a sucrose cushion, were subjected to RPA for the incorporation of packaging construct (gag) RNA (B). The mean values ± standard errors of three independent experiments, as determined by quantitation of RPA results by PhosphorImager analysis, are shown. The value obtained with reference construct pCgp-1/M54 was arbitrarily set to 100%.

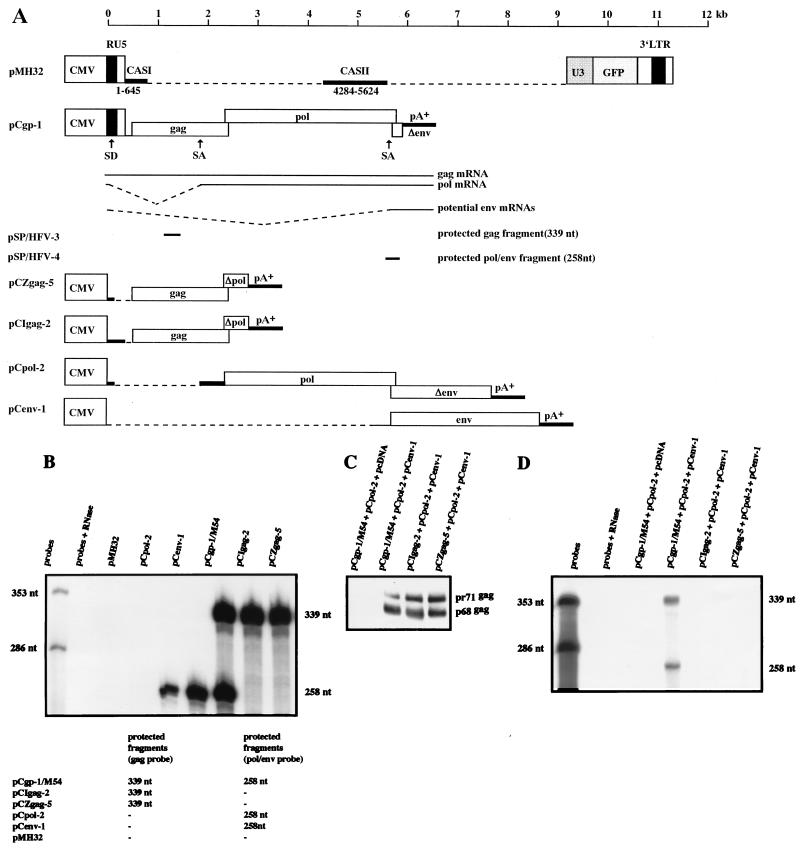

Analysis of the packaging of RNA transcribed from pol and env expression constructs.

We finally wished to determine whether RNA from the pol and env packaging constructs was possibly packaged into virions produced by transfection of cells with pCIgag-2 or pCZgag-5, since the CASII element is at least fully contained in the pol RNA. To do this, we cotransfected the respective plasmids with pCpol-2 and pCenv-1. To compensate for the generation of additional Pol protein by control plasmid pCgp-1, we used the pol gene ATG down mutant pCgp-1/M54. Due to the presence of the cis-acting U5 sequence involved in particle maturation (15), transfection of pCgp-1/M54, but not of pCIgag-2 and pCZgag-5, together with pCpol-2 and pCenv-1 essentially resulted in extracellular virions in which the C-terminal cleavage of the Gag precursor protein had taken place. FV capsids consisting of pr71/p68gag differ from pr71gag capsids in morphology and function (6, 11). Therefore, we included the pMH32 vector (14) as an additional plasmid in the transfection cocktail. This vector was chosen because it can supply the U5 sequence required for Gag cleavage to cells transfected with pCIgag-2 and pCZgag-5 and, furthermore, the RNA of this vector is not detected by the RPA probes used (Fig. 6). By this strategy, we detected bands of 339 nt that corresponded to gag mRNA and of 258 nt that potentially could be derived from gag, pol, or env RNA in total RNA preparations of cells transfected with pCIgag-2, pCZgag-5, pCgp-1/M54, pCpol-2, or pCenv-1, respectively (Fig. 6). In virions derived from cells transfected with pCgp-1/M54 together with pCpol-2 and pCenv-1, the same two bands appeared. They most likely correspond to the packaging construct gag RNA of pCgp-1. Neither band was visible by RPA in virions produced following transfection of cells with pCIgag-2 and pCZgag-5, which indicated that the subgenomic pol and env RNAs are not efficiently packaged into FVs. Thus, it appears that CASII is insufficient to mediate packaging of RNA into PFV-1 capsids produced by separate expression of Gag and Pol.

FIG. 6.

Analysis of pol and env RNA copackaging into FV vector particles. An RPA was designed to determine whether pol or env RNA is incorporated into FV vector particles. In panel A, an overview of the individual constructs and RPA probes (pSP/HFV-3 and pSP/HFV-4) used in this assay is shown. Dotted lines represent untranscribed regions or intron sequences spliced out after transfection of cells with control plasmid pCgp-1. In panel B, the result of an RPA of cellular RNA prepared after transfection of cells with the individual expression constructs is shown. Note that the vector RNA (pMH32) was not detected by either probe. Viral particles (C) were prepared from the supernatant of transfected cells and analyzed for content of RNA from packaging constructs. As shown in panel D, we found no evidence of packaging of subgenomic pol- or env-related RNA into particles produced by transfection of 293T cells with pCIgag-2 and pCZgag-5.

DISCUSSION

A lack of residual retroviral gene expression and a large packaging capacity belong to the characteristics of a good retroviral vector suitable for gene therapy applications (27, 28). The pMD9 and pMD11 vectors fulfill these requirements. Residual Gag protein translation from FV vectors was abrogated by mutation of the gag ATG within the CASI element of pMD9 and -11. In addition, we reduced the size of the U3 region within the 3′ LTR from 1423 to 219 bp, leaving only an extended region at the ppt-U3 and U3-R junctions. All of the previously identified elements conferring Tas responsiveness and the TATA box were deleted (9, 13, 22). This deletion served two functions. First, it eliminated the risk of activation of the U3 promoter in the absence of Tas by cellular transcription factors, and second, it extended the pMD vector packaging limit. Our currently best vector with the safety features incorporated into pMD and cis-acting sequences of 645 bp (CASI), 2,015 bp (CASII), and 442 bp (ppt with U3 and R of the 3′ LTR deleted) has a theoretical packaging limit of 8.5 kb before reaching the size of the PFV-1 pregenomic RNA of 11.67 kb (37), which is larger than the theoretical capacity of MuLV- or HIV-1-derived vectors (27, 28). However, in practice, the packaging capacity of retroviral vectors can be extended by 10 to 15% without significant loss of vector transfer efficiency (27, 28). This issue has, to our knowledge, not been investigated for FV vectors.

We and others recently reported that PFV-1 Gag and Pol protein expression essentially requires the R region of the 5′ LTR (15, 35). Determination of cellular RNA amounts suggested that the effect is mainly posttranscriptional (15, 35). There is no evidence for regulation at the level of RNA transport; however, the mechanism of action has remained obscure (35). Although the elucidation of this mechanism is far beyond the aim of our study, we identified the 5′ SD as the sequence in R that is responsible for the effect observed. Replacement of the authentic PFV-1 R region with heterologous intron sequences, with other retroviral leader sequences with 5′ SD sites, and even with a short sequence supplying a heterologous viral 5′ SD sequence was found to be sufficient to rescue Gag, as well as Pol, protein expression. Further studies, such as analysis of the translational efficiency of gag RNA with and without 5′ SD, are required to resolve the function of the 5′ SD in PFV-1 Gag protein generation.

Replacement of the PFV-1 leader with other sequences containing splice sites enabled us to eliminate the complete PFV-1 5′ UTR of FV vector packaging constructs without abrogating Gag and Pol protein expression. However, vector transfer was significantly reduced when these constructs were used to package FV gene transfer vectors. This limitation could be overcome by using separate gag and pol packaging plasmids. Two Gag expression constructs for efficient generation of vector capsids containing barely detectable amounts of RNA transcribed from the packaging constructs were identified. Furthermore, we were unable to detect packaging of pol and env RNA into these particles.

These results, together with those of our previous studies (14, 15), are suggestive of some hypotheses for the understanding of the molecular biology of PFV-1 and the design of packaging cell lines and PFV-1 vectors. (i) The primary packaging signal of PFV-1 is still ill defined; it may be bipartite and reside in the first approximately 650 nt of the RNA pregenome and the last approximately 2 kb of Pol. Neither signal alone is sufficient for efficient packaging. Recently, it has been shown that CASII contains an element that is able to promote HIV-1 Gag expression in the absence of the Rev/Rev-responsive element system (44). However, FV Gag expression appears to be independent of the presence of CASII. Thus, further work is required to elucidate the biochemical mode of action of CASI and -II more precisely. (ii) The authentic FV 5′ UTR is not required for Gag protein expression. However, the presence of a 5′ SD sequence is essential. (iii) The separation of gag expression and pol expression on different plasmids and the use of heterologous splice sites enabled efficient generation of vector particles while the incorporation of RNA transcribed from the packaging constructs into virus particles could be reduced to barely detectable levels. This strategy allows separation of the expression of the Gag and Pol proteins from RNA packaging. However, vector transfer rates could not be enhanced by this approach and, to our knowledge, it is unknown whether the incorporation of packaging construct RNA is of practical relevance for the safety of FV vectors. (iv) The interaction of capsid and polymerase proteins together with pregenomic RNA during the assembly of PFV-1 capsids appears to be complex and difficult to analyze since the modification of one variable may influence the other components (14, 15). The system we suggest for investigation of these complex interactions makes use of the separated gag and pol expression plasmids, which do not package their own RNA. Thus, this systems allows investigation of the constituents of PFV-1 capsids (Gag, Pol, and RNA) by alteration of an individual component with a reduced risk of affecting the others.

Acknowledgments

Martin Heinkelein and Marco Dressler contributed equally to this work.

We thank Ottmar Herchenröder for critical review of the manuscript and Bryan Cullen and Rebecca Russel for helpful discussion.

This work was supported by grants from the DFG (Re627/6-2 and Li621/2-3), the BMBF (01KV9817/0 and BEO 0312191), the Bayerische Forschungsstiftung, Sächsisches Staatsministerium für Umwelt und Landwirtschaft (13-8811.61/142), the EU (BMH4-CT97-2010), and Bayer AG. G.J. was supported by the Hector Stiftung.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achong, B. G., P. W. A. Mansell, M. A. Epstein, and P. Clifford. 1971. An unusual virus in cultures from a human nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 46:299-307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali, M., G. P. Taylor, R. J. Pitman, D. Parker, A. Rethwilm, R. Cheingsong-Popov, J. N. Weber, P. D. Bieniasz, J. Bradley, and M. O. McClure. 1996. No evidence of antibody to human foamy virus in widespread human populations. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 12:1473-1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1987. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 4.Bodem, J., M. Löchelt, I. Winkler, R. P. Flower, H. Delius, and R. M. Flügel. 1996. Characterization of the spliced pol transcript of feline foamy virus: the splice acceptor site of the pol transcript is located in gag of foamy viruses. J. Virol. 70:9024-9027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DuBridge, R. B., P. Tang, H. C. Hsia, P.-M. Leong, J. H. Miller, and M. P. Calos. 1987. Analysis of mutation in human cells by using an Epstein-Barr virus shuttle system. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7:379-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Enssle, J., N. Fischer, A. Moebes, B. Mauer, U. Smola, and A. Rethwilm. 1997. Carboxy-terminal cleavage of the human foamy virus gag precursor molecule is an essential step in the viral life cycle. J. Virol. 71:7312-7317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enssle, J., I. Jordan, B. Mauer, and A. Rethwilm. 1996. Foamy virus reverse transcriptase is expressed independently from the gag protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:4137-4141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erlwein, O., P. D. Bieniasz, and M. O. McClure. 1998. Sequences in pol are required for transfer of human foamy virus-based vectors. J. Virol. 72:5510-5516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erlwein, O., and A. Rethwilm. 1993. BEL-1 transactivator responsive sequences in the long terminal repeat of human foamy virus. Virology 196:256-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer, N., J. Enssle, J. Müller, A. Rethwilm, and S. Niewiesk. 1997. Characterization of human foamy virus proteins expressed by recombinant vaccinia viruses. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 13:517-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer, N., M. Heinkelein, D. Lindemann, J. Enssle, C. Baum, E. Werder, H. Zentgraf, J. G. Müller, and A. Rethwilm. 1998. Foamy virus particle formation. J. Virol. 72:1610-1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hahn, H., G. Baunach, S. Bräutigam, A. Mergia, D. Neumann-Haefelin, M. D. Daniel, M. O. McClure, and A. Rethwilm. 1994. Reactivity of primate sera to foamy virus gag and bet proteins. J. Gen. Virol. 75:2635-2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He, F., W. S. Blair, J. Fukushima, and B. R. Cullen. 1996. The human foamy virus Bel-1 transcription factor is a sequence-specific DNA binding protein. J. Virol. 70:3902-3908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heinkelein, M., M. Schmidt, N. Fischer, A. Moebes, D. Lindemann, J. Enssle, and A. Rethwilm. 1998. Characterization of a cis-acting sequence in the pol region required to transfer human foamy virus vectors. J. Virol. 72:6307-6314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinkelein, M., J. Thurow, M. Dressler, H. Imrich, D. Neumann-Haefelin, M. O. McClure, and A. Rethwilm. 2000. Complex effects of deletions in the 5′ untranslated region of primate foamy virus on viral gene expression and RNA packaging. J. Virol. 74:3141-3148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heneine, W., W. M. Switzer, P. Sandstrom, J. Brown, S. Vedapuri, C. A. Schable, A. S. Khan, N. W. Lerche, M. Schweizer, D. Neumann-Haefelin, L. E. Chapman, and T. M. Folks. 1998. Identification of a human population infected with simian foamy viruses. Nat. Med. 4:403-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herchenröder, O., R. Renne, D. Loncar, E. K. Cobb, K. K. Murthy, J. Schneider, A. Mergia, and P. A. Luciw. 1994. Isolation, cloning, and sequencing of simian foamy viruses from chimpanzees (SFVcpz): high homology to human foamy virus (HFV). Virology 201:187-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higuchi, R. 1990. Recombinant PCR, p. 177-183. In M. A. Innis, D. H. Gelfand, and T. J. White (ed.), PCR protocols, a guide to methods and applications. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 19.Hirata, R. K., A. D. Miller, R. G. Andrews, and D. W. Russel. 1996. Transduction of hematopoietic cells by foamy virus vectors. Blood 88:3654-3661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imrich, H., M. Heinkelein, O. Herchenröder, and A. Rethwilm. 2000. Primate foamy virus pol proteins are imported into the nucleus. J. Gen. Virol. 81:2941-2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jordan, I., J. Enssle, E. Güttler, B. Mauer, and A. Rethwilm. 1996. Expression of human foamy virus reverse transcriptase involves a spliced pol mRNA. Virology 224:314-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang, Y., W. S. Blair, and B. R. Cullen. 1998. Identification and functional characterization of a high-affinity Bel-1 DNA binding site located in the human foamy virus internal promoter. J. Virol. 72:504-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang, Y., and B. R. Cullen. 1998. Derivation and functional characterization of a consensus DNA binding sequence for the Tas transcriptional activator of simian foamy virus type 1. J. Virol. 72:5502-5509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linial, M. L. 1999. Foamy viruses are unconventional retroviruses. J. Virol. 73:1747-1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Löchelt, M., W. Muranyi, and R. M. Flügel. 1993. Human foamy virus genome possesses an internal, Bel-1-dependent and functional promoter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:7317-7321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mergia, A., and M. Heinkelein. Foamy virus vectors. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Miller, A. D. 1997. Development and applications of retroviral vectors, p. 437-473. In J. M. Coffin, S. H. Hughes, and H. E. Varmus (ed.), Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y. [PubMed]

- 28.Miller, A. D. 1992. Retroviral vectors. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 158:1-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moebes, A., J. Enssle, P. D. Bieniasz, M. Heinkelein, D. Lindemann, M. Bock, M. O. McClure, and A. Rethwilm. 1997. Human foamy virus reverse transcription that occurs late in the viral replication cycle. J. Virol. 71:7305-7311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muesing, M. A., D. G. Smith, C. D. Cabradilla, C. V. Benton, L. A. Lasky, and D. J. Capon. 1985. Nucleic acid structure and expression of the human AIDS/lymphadenopathy retrovirus. Nature 313:450-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muranyi, W., and R. M. Flügel. 1991. Analysis of splicing patterns of human spumaretrovirus by polymerase chain reaction reveals complex RNA structures. J. Virol. 65:727-735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prats, A. C., G. D. Billy, P. Wang, and J. L. Darlix. 1989. CUG initiation codon used for the synthesis of a cell surface antigen coded by the murine leukemia virus. J. Mol. Biol. 205:363-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rethwilm, A., O. Erlwein, G. Baunach, B. Maurer, and V. ter Meulen. 1991. The transcriptional transactivator of human foamy virus maps to the bel-1 genomic region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:941-945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riviere, I., K. Brose, and R. C. Mulligan. 1995. Effects of retroviral vector design on expression of human adenosine deaminase in murine bone marrow transplant recipients engrafted with genetically modified cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:6733-6737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Russel, R. A., Y. Zeng, O. Erlwein, B. R. Cullen, and M. O. McClure. 2001. The R region found in the human foamy virus long terminal repeat is critical for both gag and pol protein expression. J. Virol. 75:6817-6824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 37.Schmidt, M., O. Herchenröder, J. Heeney, and A. Rethwilm. 1997. Long terminal repeat U3 length polymorphism of human foamy virus. Virology 230:167-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmidt, M., S. Niewiesk, J. Heeney, A. Aguzzi, and A. Rethwilm. 1997. Mouse model to study the replication of primate foamy viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 78:1929-1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidt, M., and A. Rethwilm. 1995. Replicating foamy virus-based vectors directing high level expression of foreign genes. Virology 210:167-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schweizer, M., V. Falcone, J. Gänge, R. Turek, and D. Neumann-Haefelin. 1997. Simian foamy virus isolated from an accidentally infected human individual. J. Virol. 71:4821-4824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schweizer, M., R. Turek, H. Hahn, A. Schliephake, K.-O. Netzer, G. Eder, M. Reinhardt, A. Rethwilm, and D. Neumann-Haefelin. 1995. Markers of foamy virus (FV) infections in monkeys, apes, and accidentally infected humans: appropriate testing fails to confirm suspected FV prevalence in man. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 11:161-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soneoka, Y., P. M. Cannon, E. E. Ramsdale, J. C. Griffith, G. Romano, S. M. Kingsman, and A. J. Kingsman. 1995. A transient three-plasmid expression system for the production of high titer retroviral vectors. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:628-633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vassilopoulos, G., G. Trobridge, N. Josephson, and D. W. Russel. 2001. Gene transfer into murine hematopoietic stem cells with helper-free foamy virus vectors. Blood 98:604-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wodrich, H., J. Bohne, E. Gumz, R. Welker, and H.-G. Kräusslich. 2001. A new RNA element located in the coding region of a murine endogenous retrovirus can functionally replace the Rev/Rev-responsive element system in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag expression. J. Virol. 75:10670-10682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu, M., S. Chari, T. Yanchis, and A. Mergia. 1998. cis-acting sequences required for simian foamy virus type 1 vectors. J. Virol. 72:3451-3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu, S. F., D. N. Baldwin, S. R. Gwynn, S. Yendapalli, and M. L. Linial. 1996. Human foamy virus replication: a pathway distinct from that of retroviruses and hepadnaviruses. Science 271:1579-1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]