Abstract

Objective

To examine the evolution of the Medicare HMO program from 1996 to 2001 in 12 nationally representative urban markets by exploring how the separate and confluent influences of government policy initiatives and health plans' strategic aims and operational experience affected the availability of HMOs to Medicare beneficiaries.

Data Source

Qualitative data gathered from 12 nationally representative urban communities with more than 200,000 residents each, in tandem with quantitative information from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and other sources.

Study Design

Detailed interview protocols, developed as part of the multiyear, multimethod Community Tracking Study of the Center for Studying Health System Change, were used to conduct three rounds of interviews (1996, 1998, and 2000–2001) with health plans and providers in 12 nationally representative urban communities. A special focus during the third round of interviews was on gathering information related to Medicare HMOs' experience in the previous four years. This information was used to build on previous research to develop a longitudinal perspective on health plans' experience in Medicare's HMO program.

Principal Findings

From 1996 to 2001, the activities and expectations of health plans in local markets underwent a rapid and dramatic transition from enthusiasm for the Medicare HMO product, to abrupt reconsideration of interest corresponding to changes in the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, on to significant retrenchment and disillusionment. Policy developments were important in their own right, but they also interacted with shifts in the strategic aims and operational experiences of health plans that reflect responses to insurance underwriting cycle pressures and pushback from providers.

Conclusion

The Medicare HMO program went through a substantial reversal of fortune during the study period, raising doubts about whether its downward course can be altered. Market-level analysis reveals that virtually all momentum for the program has been lost and that enrollment is shrinking back to the levels and locations found in the mid-1990s.

Keywords: Medicare, HMO, health policy, public managed care, health market change

Policymakers' promotion of HMO enrollment for Medicare beneficiaries during the 1990s proved to be a risk-ridden experience for all parties. Throughout the decade, policymakers, health plans, and Medicare beneficiaries were on a roller coaster ride that provided first an exhilarating climb, then an unnerving leveling off, followed by a steep drop in Medicare HMO membership and health plan participation. Since 1998, policymakers have been distressed, health plans dismayed, and Medicare beneficiaries disturbed and dislocated by developments far different from their original expectations.

This tumultuous period in the history of Medicare's HMO program has been the focus of considerable research and commentary, reflecting the political, economic, and social salience of the Medicare program and the very visible manner in which the misfortunes of the Medicare HMO strategy have been played out. Previous empirical research on HMOs' participation in Medicare consistently found payment rates to be the most significant factor in influencing health plans' entry, retention, and overall financial success (Adamache and Rossiter 1986; Porrell and Wallack 1990; Pai and Clement 1999). Brown and Gold (1999) contributed a more holistic model of factors asserted to promote or impede the growth of Medicare managed care, and in a detailed assessment of four markets in the mid-1990s, sorted these forces into two general categories: distinctive features of Medicare managed care and market factors.

Building on previous research and conceptual frameworks, the present study explores the interplay between government policy, health plans' strategic objectives, and health plans' operational experience in the Medicare HMO program between 1996 and 2001. Data for the study come primarily from interviews conducted in 1996, 1998, and 2000 with health plans and providers in 12 nationally representative urban communities as part of the Community Tracking Study (CTS). This paper presents findings from the site visit interviews in these communities. It also discusses implications and conclusions from the analysis for policymakers and others.

One of the key lessons that can be drawn from this study is that conditioning public policy aims on the behavior of private organizations with their own goals and objectives introduces a complex chain of events that may not come to pass or may not be sustainable. Moreover, national policy initiatives in the health care realm are extraordinarily dependent on local market circumstances, as revealed in cross-market studies that capture the interaction among aims and actions of health plans, providers, and beneficiaries in diverse communities. Participation in the Medicare HMO program is a complicated choice process for all of these parties, and is affected both by actions taken by national policymakers and the strategic and tactical maneuvering by private decision makers in local markets.

Background

Medicare contracting with HMOs on a risk basis began in the early 1980s. Because Medicare payment rates to HMOs were determined by historical Medicare fee-for-service payment rates at the county level, a distinctive geographic concentration of Medicare beneficiaries in HMOs in those counties with high payment rates was quickly apparent. The number of health plans participating in Medicare's risk-contracting program grew rapidly, reaching 161 plans by 1987, but then dropped sharply, falling to 93 plans by 1991 (Rossiter 2001). In the mid-1990s, Medicare payment rates to plans were increasing much faster than commercial rates, and health plans viewed Medicare as a promising opportunity (Health Care Advisory Board 1997). By the end of the 1990s, the number of plans participating in the Medicare's risk-contracting program had tripled.

Some policymakers thought competition among HMOs was a promising vehicle for adding benefits or lowering out-of-pocket costs for Medicare beneficiaries and concluded that more should be done to promote expanded access to HMOs. More skeptical policy observers doubted whether HMOs were capable of producing cost savings for Medicare comparable to cost savings achieved for commercial purchasers. Other critics contended the administered pricing system used by Medicare was so badly flawed that the HMO program would never save money until genuine competition could be injected into it, perhaps through competitive bidding among plans (Dowd, Coulam, and Feldman 2000). Despite this ambivalence, some observers contended as many as 25 to 30 percent of Medicare beneficiaries might be in HMOs by the year 2000 (Health Care Advisory Board 1997).

These expectations about Medicare managed care, along with broader policy concerns about future federal budget deficits and Medicare shortfalls, converged into what became known as efforts to “modernize Medicare,” ultimately finding their way into the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (BBA)—a landmark piece of Medicare reform legislation. For some proponents, the centerpiece of this reform was the creation of Medicare+Choice (M+C), a new component of Medicare that was intended to offer beneficiaries a variety of health plan choices resembling the multiple health plan options offered in the private sector (Christiansen 1998). Under Medicare+Choice, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)—formerly known as the Health Care Financing Administration—was authorized to contract with “coordinated care plans”—including HMOs, preferred provider organizations (PPOs), and provider-sponsored organizations (PSOs), as well as with other entities. This policy strategy rested on a belief that by relying on private contractors to expand choices and promote competition, Medicare beneficiaries and the federal government could get more value for their spending.

The various effects of the 1997 Balanced Budget Act has been well documented. Since the implementation of this law, the number of health plans participating, markets served, and beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare+Choice has declined steadily in several waves of health plan withdrawals and retreats (Gold 2001). The decline in health plan participation has evoked consternation among Medicare beneficiaries and policymakers, who characterized plan actions as acts of “abandonment.” On the other hand, many providers, who feared that migration of increasing numbers of Medicare beneficiaries into HMOs would adversely affect them, feel they have been granted a reprieve from what they once regarded as the inevitable growth in the Medicare HMO program.

But the picture of reversal of fortune of the Medicare HMO program is far from simple and monolithic. Nearly 15 percent of Medicare beneficiaries nationwide remain enrolled in Medicare+Choice plans; and the figure exceeds 40 percent in several markets. Nationally, more than 175 plans continue to participate in the program. In some communities, Medicare beneficiaries still obtain benefits well in excess of traditional Medicare's basic benefits for little or no out-of-pocket payments. Furthermore, Congress recently has acted twice to reverse some adverse impacts of the Balanced Budget Act, and the effects of these changes are still being experienced (Medicare Payment Advisory Commission 2000; 2001).

Study Methods

This study of the influence of government policy initiatives, health plan strategic aims, and health plan operational experience on Medicare participation is based on data from the Community Tracking Study of the Center for Studying Health System Change and information from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The CTS is a longitudinal, multimarket, multimethod project that is monitoring and chronicling health system changes in 60 randomly selected, nationally representative markets across the country (Kemper et al. 1996).

As part of the CTS, in-depth case studies are being conducted in 12 randomly selected, nationally representative communities with more than 200,000 residents. In 1996, 1998, and 2000–2001, teams of researchers made site visits to the 12 communities to conduct extensive telephone and in-person interviews with informants representing the perspectives of purchasers, providers, health plans, and policymakers. Building on baseline data from earlier rounds, in the third round of site visits in 2000–2001, there was a focus on collecting data related to the Medicare HMO experience. Interviewees were asked retrospective questions about changes in the Medicare HMO experience during the previous four years. In each of the 12 markets, interviews were conducted with three to six health plans drawn from the dominant health plans affiliated with multistate plans, Blue Cross and Blue Shield Plans, and other locally based health plans. A total of 210 health plan informants were interviewed across the sites. Informants included executives responsible for operations, marketing, medical management, provider network development, and the Medicare product, if the plan was active in this area. Additional insights regarding Medicare came from interviews with physicians, hospitals, policymakers, and, in some instances, employers and benefits consultants.

The 12 communities selected for in-depth case studies of health system change in local communities in the CTS range from markets with some of the greatest Medicare HMO penetration to markets with no Medicare HMO enrollment at all. As Table 1 illustrates, the 12 communities can be divided into four clusters based on Medicare HMO enrollment: high-, moderate-, limited-, and minimal-penetration markets. Payment rate variation and cross-market plan participation levels are also reflective of national variation in the Medicare HMO experience. Thus, these 12 communities present a suitably representative picture of changes occurring in Medicare's HMO program in the period beginning in 1996.

Table 1.

Medicare+Choice HMO Market Penetration, Overall HMO Penetration, and Medicare Payment Rates in Twelve Urban Communities

| Medicare HMO Penetration (%)1 | Overall HMO Penetration (%) | Medicare Payment Rate ($)2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Markets by Level of Medicare HMO Penetration | 1996 | 1998 | 20011 | 1996 | 1998 | 2000 | 1996 | 1998 | 2000 | 2002 |

| High penetration3 | ||||||||||

| Orange County4 | 41.7% | 43.1% | 42.1% | 40.5% | 45.3% | 47.1% | $545 | $584 | $610 | $640 |

| Phoenix | 38.1 | 43.4 | 43.8 | 33.1 | 34.2 | 34.7 | 472 | 499 | 524 | 553 |

| Miami | 37.2 | 43.4 | 45.7 | 52.9 | 61.1 | 43.8 | 687 | 763 | 794 | 834 |

| Moderate penetration3 | ||||||||||

| Seattle | 30.5% | 33.4% | 26.3% | 20.8% | 25.9% | 19.2% | $410 | $437 | $483 | $553 |

| Boston | 15.5 | 23.0 | 22.0 | 36.9 | 47.7 | 43.1 | 532 | 581 | 604 | 635 |

| Cleveland | 11.6 | 22.2 | 19.3 | 19.8 | 28.9 | 30.6 | 516 | 553 | 576 | 605 |

| Limited penetration3 | ||||||||||

| Lansing | 8.7% | 12.1% | 12.3% | 39.5% | 41.1% | 33.4% | $477 | $500 | $520 | $553 |

| Little Rock | 4.6 | 9.9 | 8.7 | 18.1 | 26.2 | 21.7 | 444 | 477 | 498 | 553 |

| Northern New Jersey | 4.1 | 10.0 | 8.5 | 21.1 | 23.9 | 31.5 | 518 | 554 | 579 | 608 |

| Minimal penetration3 | ||||||||||

| Indianapolis | 4.0% | 6.2% | 5.0% | 20.2% | 24.4% | 21.9% | $456 | $486 | $506 | $553 |

| Greenville | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 5.6 | 11.1 | 11.2 | 327 | 367 | 405 | 553 |

| Syracuse | 0 | 1.1 | 0 | 18.0 | 19.4 | 15.5 | 368 | 375 | 418 | 553 |

| NATIONAL AVERAGE | 11.0% | 16.1% | 14.9% | 24.0% | 29.2% | 28.1% | $436 | $468 | $500 | $570 |

Data are December for 1996 and 1998 and March for 2001. Enrollment is Coordinated Care Plans (CCP) unless otherwise noted.

Payment rate for largest county in Metropolitan Statistical Area. National data represent national per capita spending on enrollees in CCP; figures are for the month December for 1996–2000 and January for 2002.

High- and moderate-penetration markets have enrollment; above the national average limited and minimal below average.

Medicare HMO penetration includes cost and demonstration plans with at least 1,000 beneficiaries. In Indianapolis, one cost plan has most of the enrollment.

Source: Based on data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (formerly the Health Care Financing Administration) and the Interstudy Competitive Edge 7.1, 9.1, 11.1.

The 12 communities include a diverse set of health plans that illustrate health plans' varied strategic objectives and operational experiences. Two of the largest health plans that participate in Medicare's HMO program—PacifiCare and Humana—are found in a number of the 12 communities. Some investor-owned multistate firms, active in entry and exit in recent years—Aetna, CIGNA, and United—also have plans in several of the 12 markets. Some of the most experienced Medicare plans in the country—Group Health and Kaiser Permanente—are also prominent players in the studied markets, as are other traditional HMO plans including Harvard Pilgrim, Tufts, AvMed, and M-Plan. In each of the 12 communities, interviews were also conducted with Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans to obtain their perspectives, because in addition to participating in M+C, many Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans are also very active in the Medigap market.

Findings

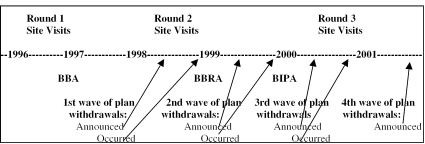

We examined how health plan participation decisions were affected by the interplay of government policy initiatives, health plan strategic aims, and health plan operational experiences over the study period. The timeline shown in Figure 1 below relates the broad federal policy context to the experience of health plans observed in the site visits to the 12 study communities conducted in 1996, 1998, and 2000–2001. When CMS announces new payment rates, plans face a deadline for announcing their intentions to enter or withdraw; as Figure 1 shows, they actually enter or withdraw several months later. Legislative changes such as the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 are typically phased in; thus, the impact of such changes is progressively experienced as various provisions become effective (Christiansen 1998).

Figure 1.

Timeline Showing Relationship between Study Site Visits to the Twelve Communities, Plan Decisions about Participating in Medicare+Choice, and Legislation

Key: BBA=Balanced Budget Act of 1997; BBRA=Balanced Budget Refinement Act of 1999; BIPA=Beneficiary Improvement and Protection Act of 2000 Source: Data on waves of plan withdrawals are from Gold 2001.

Round One Site Visits (1996)

In 1996, during the first round of site visits to the 12 communities, health plans' interest in Medicare enrollment was growing in all markets, including those with little or no enrollment. Orange County, Phoenix, and Miami, the markets with high Medicare HMO penetration, had Medicare HMO penetration rates that exceeded 35 percent (Table 1). Seattle, a moderate-penetration market, had rapidly jumped to 30 percent penetration by 1996 following the growth in PacifiCare's membership to forty thousand within three years of market entry in 1993. In Boston and Cleveland, two other moderate-penetration markets, Medicare HMO enrollment nearly doubled or tripled in the same period. Among the markets with limited or minimal Medicare HMO penetration, expectations of growth in 1996 were voiced by plans set to offer or expand a Medicare product. Competition among health plans was keen in several markets, as evidenced by the presence of six or more plans in seven of the twelve markets; in many cases, though, plans had just launched new Medicare products.

Policy Context

Variation in Medicare HMO penetration levels in 1996, consistent with prior research, was correlated with Medicare payment rates, particularly at the extremes. Medicare payment rates for the largest county in each of the 12 markets from 1996 to 2001 are shown in Table 1. In Miami and Orange County, high Medicare HMO penetration markets, Medicare payment rates were well above the national average. Syracuse and Greenville had the lowest Medicare payment rates and virtually no enrollment in Medicare HMOs. Other markets showed a more mixed pattern: Seattle's and Phoenix's Medicare HMO penetration levels were higher than one might expect given payment levels; Boston and northern New Jersey had Medicare payment rates that implied higher penetration than was observed. In most markets, high overall HMO penetration is correlated with high Medicare HMO enrollment. Again, however, there are important exceptions such as Lansing and Boston, where high overall HMO penetration does not portend high Medicare HMO penetration. Notably, Phoenix and Seattle are the only markets studied where Medicare HMO penetration consistently exceeded the marketwide commercial HMO penetration.

Plans' Strategic Objectives

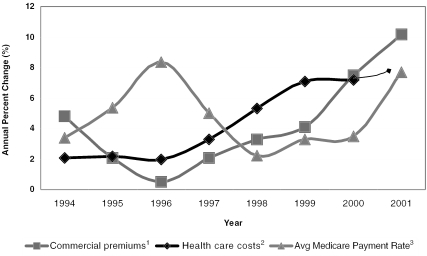

By 1996, health plans' broad strategic considerations fueled interest in adding or expanding their product lines. Growth in membership and revenue was a prominent goal in nearly all plans in all 12 markets. With commercial premium increases trending downward and Medicare payment trends moving upward sharply (Figure 2) health plans viewed Medicare as a largely untapped market, particularly in many markets with moderate or low Medicare HMO penetration. In Indianapolis, for example, only 6,000 out of 150,000 Medicare beneficiaries were in HMOs. Many plans sought growth even at the expense of income in the near term. In northern New Jersey in 1996, a Medicare executive noted “the focus was on just getting Medicare members in the door, even if it meant losing money for a period of time.” Another executive in a low-penetration market commented, “[W]e knew rates were low, but we were expecting to benefit from relatively good increases in the rates that Medicare had been paying before the BBA.” With Medicare payment increases rising faster than health care costs, plans could offer enriched benefits as a powerful inducement to prospective members.

Figure 2.

Trends in Medicare+Choice Spending, Commercial Premiums, and Commercial Health Care Costs, 1994–2001.

1Premiums are for large firms with 200+ employees. 2The 2001 estimate is for January through March, compared with corresponding months in 2000. 3Calculated as total payments divided by total enrollment for coordinated care plans in December of each year. Sources: Premiums—Kaiser/Health Research and Educational Trust Employer Health Benefits Survey for 1998–2001 and the KPMG survey for 1991–1997; health care costs—Milliman USA Health Cost Index ($(0 deductible); M+C spending—Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Medicare Managed Care Contract Plans Monthly Summary Report.

In markets with high Medicare HMO penetration, plans offered zero-premium products to beneficiaries and largely unlimited drug benefits. The trend toward reducing premiums was spreading to markets with moderate Medicare HMO penetration such as Seattle, Cleveland, and Boston for the first time, because plans saw lowering premiums as a crucial element in promoting growth. Plans like PacifiCare that targeted Medicare growth had led the way with aggressive marketing of the Medicare HMO option. Well-established locally based plans that already offered enrollment to its members who aged into Medicare, such as Group Health in Seattle, found the zero-premium product thrust upon them by competing plans, and they too were soon reducing or eliminating premiums.

Another motivator for HMOs to expand Medicare membership in 1996 was that plans wanted to expand and solidify provider networks for all of their managed care products. Providers had reconciled themselves to the idea that overall HMO enrollment would continue to soar. In fact, some providers were sponsoring their own plans or positioning themselves to form integrated delivery systems or create contracting entities to assume risk-based payment arrangements from health plans. A number of providers even advocated for increased regulatory flexibility for provider-sponsored enterprises to compete head-to-head with HMOs, a movement that led to the provider-sponsored organization (PSO) option under Medicare+Choice. Table 2 shows the number and diverse types of HMOs participating in Medicare in 1996. Competing plans were found in nine markets. Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans participated in 11 of the 12 markets; and multistate plans were found in eight of the markets.

Table 2.

Number and Types of Plans Participating in Medicare+Choice in Twelve Urban Markets

| Number of Plans with Enrollment1 | Types of Plans Participating | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Markets by Level of Medicare HMO Penetration | 1996 | 1998 | 20011 | 1996 | 20011 | |

| High penetration2 | ||||||

| Orange County3 | 14 | 12 | 10 | 7M, 2B, 5L | 5M,2B,3L | |

| Phoenix | 8 | 9 | 7 | 4M,1B,3L | 5M,2L | |

| Miami | 9 | 10 | 9 | 5M,1B,3L | 3M,1B,5L | |

| Moderate penetration2 | ||||||

| Seattle | 6 | 5 | 2 | 2M,1B,3L | 1M,1L | |

| Boston | 7 | 6 | 5 | 2M,1B,4L | 1B,4L | |

| Cleveland | 7 | 10 | 7 | 4M,1B,2L | 2M,1B,4L | |

| Limited penetration2 | ||||||

| Lansing | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1B | 1B | |

| Little Rock | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1M,1B | 1B | |

| Northern New Jersey | 5 | 8 | 4 | 3M,1B,1L | 3M,1B | |

| Minimal penetration2 | ||||||

| Indianapolis | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1M,1B,1L | 2L | |

| Greenville | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1B | — | |

| Syracuse | 0 | 1 | 0 | — | — | |

| TOTAL | 63 | 68 | 48 | 29M,12B,22L | 19M,8B,21L | |

Data are December for 1996 and 1998 and March for 2001. Enrollment is Coordinated Care Plans (CCP) unless otherwise noted.

High- and moderate-penetration markets have enrollment; above the national average limited and minimal below average.

Includes cost and demonstration plans with at least 1,000 beneficiaries.

Key: M=multistate plan; B=Blue Cross/Blue Shield plan; L=locally based plan

Source: Based on data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (formerly the Health Care Financing Administration).

Plans' Operational Experience

The movement of Medicare beneficiaries into HMOs was a development of singular importance for hospitals and physicians heavily reliant on Medicare revenues. The importance of this development was particularly evident during the first round of site visits in 1996, when providers feared that migration of increasing numbers of Medicare beneficiaries into HMOs would adversely affect their revenue. Many providers in markets with high or moderate Medicare HMO penetration had decided as a defensive maneuver to join networks or form subnetworks that contracted with Medicare HMOs. Plans with extensive experience in Medicare, such as PacifiCare, had pioneered the use of global or shared capitation arrangements with groups of physicians and health systems in the form of “percentage-of-premium” contracts, and variants of these arrangements became common in several markets, including markets beyond those PacifiCare entered.

Percentage of premium arrangements give providers significant “skin in the game,” in the parlance of plan network executives, and risk-bearing provider enterprises commonly had utilization management delegated to them to bear the consequences of their own clinical decisions. The arrangements created strong incentives for physicians to reduce hospitalization rates among beneficiaries and to reap the gains of redistribution of dollars. The threat to hospital revenues led some hospitals to describe the Medicare HMO as the “product from hell.” Percentage-of-premium arrangements had an added appealing feature for plans of building in an automatic annual adjuster, typically the rate of increase that Medicare granted to plans each year when payments levels were updated. These arrangements were well established in the three high Medicare HMO penetration markets in 1996, and they had begun spreading to the three moderate-penetration markets, as well.

Round Two Site Visits (1998)

The second round of site visits, in 1998, occurred when several facets of the BBA were being implemented (see Figure 1). As a result, the interviews conducted in this round of site visits revealed very mixed views toward Medicare HMO enrollment among health plans. Looking back to 1996, plans related how much enrollment growth up through 1998 had occurred, while at the same time expressing trepidation and anger related to key features of the BBA. A number of plans had already responded to the 1997 act by announcing strategic retreats from selected markets or submarkets and were being widely vilified for “abandoning” seniors. Other plans expressed hope that as Congress discovered unintended consequences of the BBA, it would take remedial steps.

Policy Context

In 1998, Medicare HMO membership in the 12 markets had grown since 1996, and six markets—Orange County, Phoenix, Miami, Cleveland, Little Rock, and northern New Jersey—had experienced net increases in plan participation (see Table 2). What was most striking in this round of site visit interviews was the broadening of Medicare HMO enrollment across all markets but one (Greenville). The high Medicare HMO penetration markets—Orange County, Phoenix, and Miami—had all exceeded 40 percent penetration. The moderate-penetration markets—Seattle, Boston, and Cleveland—also grew, with membership increases of 50 percent in Boston and nearly 100 percent in Cleveland. Medicare HMO enrollment also was radiating out to previously underserved markets. Large increases were evident in limited-penetration markets of Lansing, northern New Jersey, and Little Rock, though they still included only about 10 percent of potential enrollees. In 1998, in several markets, Medicare HMO enrollment was growing even faster than commercial HMO membership.

The passage of the 1997 Balanced Budget Act had a rapid, chilling impact on these trends. The most immediate effect on health plans came from changes in the rate-setting method designed to reduce disparities in the traditional payment methodology that had led to dramatic geographic variation in Medicare HMO penetration levels. These changes were intended to redistribute payment increases from higher payment to lower payment markets to expand access in markets with low penetration. Reductions in the growth of payments to plans were compounded by the link to growth in Medicare fee-for-service payments, which also declined due to the BBA. In markets where the payment level exceeded the national average, the rate of increase was effectively limited to 2 percent. The concerns of health plans were amplified by other changes in the 1997 Balanced Budget Act, including increased administrative burdens associated with the regulatory complexity of the Medicare+Choice structure and a proposal to phase a risk-adjustment scheme into Medicare+Choice payments. The Balanced Budget Act's reductions in Medicare fee-for-service payments to providers also created financial distress, which, in turn, would impel many providers to negotiate more aggressively with health plans.

The 2 percent limit had an immediate influence on plans and beneficiaries in many markets with high Medicare HMO penetration, the ones where rates had historically been well in excess of the national average. Plans in these markets bitterly complained that a 2 percent increase did not meet annual increases in medical costs that were trending upward. A number of plans selectively retreated from parts of their markets, such as suburban or rural counties, where they claimed lower payment rates made the product unprofitable. This resulted in a slowdown in the rate of enrollment growth in these markets. Payment increases in markets with Medicare HMO penetration below the national average were not large enough in 1998 to drive significant growth in membership in these markets. Many HMOs began to reconsider their plans to enter or expand in moderate penetration markets like Seattle and Cleveland. Three plans in each of these two markets would subsequently exit by 2000. Some HMOs in other markets also aborted Medicare product planning, and virtually no provider enterprises chose to enter via the PSO option. The net result was that the overall growth in national enrollment leveled off, after years of rapid growth.

Plan Strategic Objectives

The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 was a sharp jolt to health plans with strong commitment to expand or to introduce a Medicare HMO product. A number of plans in markets with high or moderate Medicare HMO penetration had expected that employer-sponsored retiree groups would drive additional growth in the Medicare HMO product. Providers in several markets appeared willing to enter into Medicare networks on a risk basis, as they sought to lock in both revenues and existing referral relationships to fend off competitors. In Indianapolis, for example, a number of hospital-sponsored physician–hospital organizations (PHOs) had positioned themselves for risk-contracting arrangements for soon-to-be developed Medicare products. HMOs, particularly in limited- and minimal-penetration markets, contemplated expanding Medicare membership for defensive purposes to preempt emergent opportunities for provider-sponsored plans.

By 1998, as Medicare premium increases fell below rising health care costs and lagged behind commercial premium increases (Figure 2), health plans that had once considered the Medicare market to be lucrative now saw a significant reversal of fortune—and many reversed the direction of their participation. The pattern of plan withdrawal was clearly shaped by Medicare payment rates. Markets with low Medicare payment rates saw interest fade quickly, while markets with high Medicare payment rates like Miami, Orange County, and Boston saw membership initially stop growing but not decline. In markets where Medicare payment rates were low to begin with, such as Seattle, a number of entering plans reevaluated and aborted participation decisions. Where interest had been tentative because of unproven beneficiary or provider support, such as Indianapolis, the 1997 Balanced Budget Act essentially put an end to expectations among plans that this was a product line worth pursuing. In several markets, late entrants with relatively small memberships found the administrative effort to comply with a complex and unstable public program was disproportionate relative to potential gains.

Several investor-owned, multistate plans announced their intentions to respond to the Balanced Budget Act by selective retreats starting in 1998, and they attracted the first wave of ire and disdain. Health plan withdrawals from Medicare began to spread across markets, particularly where Medicare HMO penetration was low, the number of plans was limited, or the history of zero premiums and unlimited drug benefits was short. Multistate plan retreats were more likely to jettison their Medicare product. Locally based plans were less prone to alter participation levels, in part because they had continuing relationships with members who had “aged-in” to the Medicare product or because of concerns about maintaining provider relationships and community reputation. Virtually all plans acknowledged, however, that, in the face of the Balanced Budget Act, much of the enthusiasm for marketing was lost. A number of plans admitted that to avoid invoking criticism for withdrawals, they simply stopped marketing to individuals, engaging in what they called “silent withdrawals” or “soft freezes” that leveled off or reduced Medicare enrollment.

Plans' Operational Experience

Many plans entering the Medicare market in 1996 and 1997 had invested in care management programs for senior members with chronic conditions and crafted new contracting arrangements with physician groups and integrated delivery systems. In both instances, they drew heavily from the expertise of the more experienced Medicare risk plans. A drug benefit also was viewed as integral to ensuring that Medicare beneficiaries could be effectively treated in the most appropriate setting to avoid higher cost conditions and complications. Other plans touted the degree to which Medicare enrollment enabled them to develop an overall membership base broadly representative of the community as a whole, and to build a continuum of care to serve this population. Experienced Medicare plans reported dramatic drops in inpatient use among beneficiaries that were attributed to success in managing care and alignment of incentives.

Plans hard fought progress in these areas was undermined by the Balanced Budget Act as the 2 percent cap in payment were seen as inadequate to meet increases in rising costs, particularly pharmacy expenses which were rising rapidly during this period. Plans in high Medicare HMO penetration markets (Orange County) and moderate-penetration markets (Seattle) with percentage-of-premium contracts were hard hit by the payment cap, as provider groups refused to continue with such contracts since they, rather than the health plans, bore the brunt of increasing medical expenses. Provider refusal to accept risk forced plans to reconsider benefits and premium arrangements offered to beneficiaries, resulting in more cost and fewer benefits for beneficiaries. Zero-premium products began to decline while drug benefits shrunk, particularly in markets with lower payment rates. Hospitals, already hurting from Balanced Budget Act-related payments cuts, began to negotiate more aggressively with plans and jeopardized percentage-of-premium contracts. The much-anticipated PSO option for provider systems to compete with HMOs failed to materialize. With few new entrants and several health plans announcing their intentions to leave markets, plans remaining in Medicare found increased demand from beneficiaries wanting to stay in an HMO. This further taxed the capacity of shrinking provider networks.

All of these problems would worsen in the years after 1998 as broader developments beset HMOs: a growing backlash against the HMO product, increasing disenchantment of providers with risk-based payments, and financial distress for both plans and providers. For investor plans with major exposure in Medicare such as PacifiCare and Humana, deterioration in that market had a magnified effect as Wall Street expressed its displeasure through lower stock prices. Some plans in 1998 said they would defer their responses to the Balanced Budget Act, hoping repairs would be made once negative implications were realized. In fact, changes were to be forthcoming, but not until a deteriorating situation worsened and the dissatisfaction among all parties intensified.

Round Three Site Visits (2000–2001)

During the third round of site visits to the 12 communities begun in June 2000 and completed in January 2001, the trajectory of health plan withdrawals continued, accelerating from 13 plan withdrawals in 1998 to 21 in 2000. Nearly two-thirds (13) of the 21 plan withdrawals in 2000 were by plans that remained in the market but ceased to offer a Medicare product. Withdrawals occurred in 10 of the 12 markets. In a number of respects, the Medicare HMO program in 2001 was returning to the shape and scope of the program five years earlier (see Table 1). In 2000, Medicare's HMO program was still strong in markets with high Medicare payment rates such as Miami, where plan, provider, and beneficiary participation has been impervious to Balanced Budget Act changes. But expansion to other markets observed in the late 1990s has abated, and health plan participation was in decline nearly everywhere. These developments led observers in some communities to characterize the status of the Medicare+Choice program as being in “free-fall” in their markets.

Policy Context

Congress attempted to rescue the Medicare HMO program with two pieces of remedial legislation—the Balanced Budget Refinement Act of 1999 (BBRA) and the Benefits Improvement and Protection Act of 2000 (BIPA)—but not until deterioration in the program snowballed further. This deterioration is in part the result of payment provisions in the Balanced Budget Act that adversely affected hospitals and reduced their willingness to contract with Medicare plans. Medicare beneficiaries in HMOs have experienced significant disruptions, notably the large wave of plan withdrawals that was announced in mid-2000 and occurred on January 1, 2001, when nearly one million Medicare beneficiaries left HMOs and total Medicare+Choice enrollment fell below six million.

When Congress passed BIPA in 2000, the round three site visits were nearly over. For that reason, it was not possible to assess fully how these latest legislative changes would influence health plans' future plans. The BIPA provided additional dollars for plans and providers to reduce some of the distress both were feeling. But raising the minimum premium increases for markets above the national average from 2 to 3 percent, for just one year, was not expected to assuage concerns of plans. One Medicare executive sardonically noted that a 1 percent increase “may allow us to buy our members one more pill per month.” Other plans suggested that Medicare payment increases would flow mainly to providers to forestall further pushback and network collapse. The impact of a new floor on premiums set for smaller metropolitan markets meant substantial increases for some plans (see Table 1). Based on further HMO withdrawal decisions announced in January 2002, BIPA has not succeeded in slowing withdrawals nationally or within the 12 study markets (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2001).

Plans' Strategic Objectives

Health plans' participation was considerably different in the 12 markets in March 2001 than in 1996 (see Table 2). The changes reflected both structural changes in the managed care market and policy decisions about Medicare. Multistate, investor-owned plans have led the way in market withdrawals, with participation dropping from 29 plans in 1996 to 19 in 2001. A number of multistate plans—including United, Aetna, and CIGNA—were very public about their strategic reassessments of the Medicare line of business. Their participation in the markets with moderate or limited Medicare HMO penetration shrunk from 12 to only 6 plans. Blue Cross/Blue Shield plans' participation also declined from 12 participants in 1996 to 8 participants, though Blue's plans remained involved in 7 of the 12 markets studied. Locally based plans also reduced their participation, down from 22 plans in 1996 to 20 plans by 2001, but these plans remained strongly entrenched in the six markets with moderate or high HMO penetration. Erosion in Medicare HMO benefits, especially in drug coverage, was widespread. Premiums had been introduced by plans that had never had them previously, or reintroduced by plans that had eliminated them just a few years earlier (Cassidy and Gold 2000).

Health plans continued to respond to underwriting cycle pressures evident in the earlier periods and made many strategic changes that affected their decision to participate in Medicare (Lesser and Ginsburg 2001). They have shifted their primary goal from increasing membership or revenues to improving profitability across all lines of business. This new emphasis puts in jeopardy low- or no-margin lines of business, including Medicare and other lines of business for which future premium increases are constrained and nonnegotiable. Many plans also reported during the round three site visits that traditional, tightly managed HMO products on which most Medicare+Choice plans are based are falling out of favor with consumers and are therefore no longer growing. This observation is borne out in Table 1, which shows that total HMO penetration declined in 7 of the 12 markets between the second and third rounds of site visits. Likewise, many plans are redesigning products with expanded cost-sharing provisions for members to try to cushion the impact of increases for employers. Although sharply raising premiums to Medicare members is an option to generate more Medicare revenue, plans have been reluctant to do this because it may increase the chance of adverse selection, as only Medicare beneficiaries who anticipate high medical expenses may be willing to pay high premiums.

Plans with a strong commitment to Medicare continue to express great displeasure with both the program's administrative demands and the degree of exposure to adverse publicity that contracting with Medicare entails. They report that they have had to make major investments in updating current members about Medicare changes, explaining why they have made the modifications in products, and forewarning members further changes will be forthcoming as the Medicare HMO program remains in flux. Coupled with the friction that recent changes have engendered in provider relationships, several plans feel that relationship damage control has become a consuming exercise in the Medicare line of business.

Plans' Operational Experience

Perhaps the most demanding operational challenge faced by health plans reported in the third round of site visits was provider network renegotiation and reconfiguration. As provider payment reductions scheduled to be phased in by the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 snowball despite BBRA and BIPA modifications, the impact on hospitals has become more pronounced in virtually all 12 markets. Many hospitals and health systems responded to financial distress by refusing contracts with plans for products that do not compensate them adequately. In some cases, plans caught in the squeeze between more demanding providers and increasingly disgruntled members and employers across all of their product lines have relented to provider pushback, in many instances with higher payments. In other cases, where they did not, highly visible showdowns have occurred (Strunk, Devers, and Hurley 2001). When plans have risk arrangements with provider organizations, as is common in markets with high or and moderate Medicare HMO penetration, negotiations have become even more contentious, because providers' appetite for risk has declined in many markets. Plans have had to step back from these arrangements or refine the scope of risk being shared, often carving out items like pharmacy costs that providers claim are unmanageable.

The implications for Medicare have been profound, given the prominence of percent of premium contracts in this product line. The 2 or 3 percent increase for plans received in many markets was too meager for many risk-bearing providers to accept. Many refused to renew contracts or demanded substantial changes in both rates and methods of payment. Plans in this predicament have no recourse but to pay more for care or face the loss of their Medicare networks and, correspondingly, the Medicare line of business. For example, PacifiCare, a plan with very substantial exposure in Medicare, has had to undertake major redesign of its contracting strategies in Seattle, Phoenix, and Orange County. In nearly every market, plans express anxiety that additional concessions will be needed as providers become more aggressive in negotiations.

Discussion and Implications

The Medicare HMO experience has been the focus of an extensive amount of research and commentary in recent years. The results from the study in the 12 nationally representative communities presented here add to the literature by synthesizing information drawn from systematically tracking experience in diverse markets over the eventful period from 1996 to 2001. Several key conclusions can be drawn from this local market perspective. Most importantly, public policy efforts to promote expanded access to HMOs for Medicare beneficiaries have not been successful. Between 1998 and 2001, Medicare penetration declined in 8 of the 12 communities studied and was unchanged in 2 of the 12 communities, and plan participation in Medicare in the markets was down by nearly 25 percent. Cost sharing was higher for Medicare beneficiaries in remaining plans, and their benefits were typically reduced during this period.

Some observers ascribe a portion of the responsibility for lack of expansion to ill-advised changes related to the 1997 Balanced Budget Act. It is important to note, however, that health plans' evolving strategies and operational experience have amplified the effects of legislative and regulatory changes. During the past half-decade, the attractiveness of Medicare to health plans has waxed and then waned sharply. Trends in Medicare and commercial premiums and in underlying costs of care have displayed dramatic changes in their relative positions affecting the broader strategies embraced by health plans. Steep increase in participation chronicled in the mid-1990s was spawned in part by a desire among plans to expand membership and diversify product lines. Conversely, retrenchment and withdrawals in subsequent years were affected by broad strategic aims among health plans, including a renewed focus on profitability. In addition, overall HMO penetration dropped in 9 of the 12 markets between 1998 and 2001 as consumers and providers grew disenchanted with HMOs and members migrated to less restrictive arrangements. It is hardly surprising that these findings indicate that corporate self-interest aims can amplify, mute, or simply trump policy initiatives.

Interviews with plans across all types of markets reveal disappointment with the actions of policymakers and the direction of the Medicare product in recent years. For many years, pioneering risk-contracting plans referred to their doubts about the reliability of contracting with the Medicare program as the “public sector risk factor” (Bell 1987). The past few years have brought this concern back to life and sown seeds of doubt and distrust that will be hard to dispel, particularly among plans that have withdrawn from participation in Medicare+Choice. This atmosphere of distrust will be a significant impediment to launching future reform efforts. As Medicare payment rates increases have slowed while financial needs of providers have seemed to grow, relationships between plans and providers have also suffered. Health plans note that the momentum of rapid Medicare HMO enrollment that convinced many providers to join networks has now been lost. As Medicare HMO enrollment declines and the Medicare HMO product falls into further disfavor, it will be exceedingly difficult to draw providers into networks for the product.

The ups and downs of the Medicare HMO market—as well as the failure of most other Medicare+Choice options to emerge—have raised doubts in the minds of policymakers about the reliability of private plans as instruments for achieving public policy goals. Some policymakers believe that Medicare's experience with plan retreats and withdrawals confirms their worst suspicions about plan motives, methods, and dependability. Other policy observers have little sympathy for plans that have promised their members and network providers more than what they can deliver. These observers contend that if plans will not adjust member premiums or benefits to bring revenues and expenses back in line then they cannot succeed financially and should leave the market. These critics conclude that the withdrawal from the market of a sufficient number of plans may indicate that a Medicare HMO strategy cannot be sustained. Ultimately, the past decade underscores that Medicare's reliance on voluntary participation by private plans carries with it an inescapable measure of instability.

Medicare's structure and relative inflexibility are—and will remain—significant impediments in the face of transitioning managed care markets. Given the pace of change in the managed care market in terms of models, products, and practices, slow moving efforts to modernize Medicare are unlikely to keep up with these developments. Even an apparently well-thought-out initiative like the competitive-bidding demonstrations to devise a new method of determining payment rates was badly mauled when it was overtaken both by events in local markets and shifting political sentiments toward managed care plans in general.

The larger findings from the third round of site visits to the 12 communities offer a final note of caution that should inform Medicare's HMO strategy (Lesser and Ginsburg 2001). Clearly, health plans have lost considerable traction in their efforts to contain costs as premium increases have soared and returned to the levels of a decade ago. Health plans' products and practices are moving toward less aggressively managed care built around broader networks of providers and accompanied by higher cost-sharing provisions for members. Brinkmanship and instability have become common in plan–provider contracting, and many providers are actively seeking a return to more traditional methods of payments. Moreover, benefits packages are being trimmed while adding more cost-sharing by consumers, particularly for pharmaceuticals. Anticipated improvements in chronic care management, application of information technology, more rigorous cost-effectiveness assessment of new technology, and more consumer-friendly interaction have proven elusive. Taken together, these disappointing and perhaps ominous developments should at least underscore the need to reconsider just what it is that HMOs or other coordinated care plans can bring to the Medicare program.

REFERENCES

- Adamache K, Rossiter L. “The Entry of HMOs in the Medicare Market: Implications for TEFRA's Mandate.”. Inquiry. 1986;23(4):349–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell C. “Fallon Community Health Plan, a Medicare Experience.”. In: Rahm G, editor. Hospital Sponsored Health Maintenance Organizations. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Publishing; 1987. pp. 215–30. [Google Scholar]

- Brown R, Gold M. “What Drives Medicare Managed Care Growth?”. Health Affairs. 1999;18(6):140–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.6.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy A, Gold M. Medicare+Choice in 2000: Will Employees Spend More and Receive Less? New York: Commonwealth Fund; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services “Managed Care Market Penetration Quarterly State/County/Plan Data Files.”. 2001. Available at http://www.hcfa.gov/medicare/mpscpt1.htm Accessed November 20, 2001.

- Christiansen S. “Medicare+Choice Provisions in the Balanced Budget Act of 1997.”. Health Affairs. 1998;17(4):224–31. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.17.4.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd B, Coulam R, Feldman R. “A Tale of Four Cities: Medicare Reform and Competitive Pricing.”. Health Affairs. 2000;19(3):9–29. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.5.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold M. “Medicare+Choice: An Interim Report Card.”. Health Affairs. 2001;20(4):120–38. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.4.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Care Advisory Board . Executive Briefing on Medicare Strategy. Washington, DC: The Advisory Board; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kemper P, Blumenthal D, Corrigan J, Cunningham P, Felt S, Grossman J, Kohn L, Metcalf C, St. Peter R, Strouse R, Ginsburg P. “The Design of the Community Tracking Study: A Longitudinal Study of Health System Change and Its Effects on People.”. Inquiry. 1996;33(2):195–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesser C, Ginsburg P. Back to the Future? New Cost and Access Challenges Emerge: Initial Findings from HSC's Recent Site Visits. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change; 2001. Issue brief no. 35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission . Report to Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Washington, DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; [Google Scholar]

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission . Report to Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Washington, DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pai C, Clement D. “Recent Determinants of New Entry of HMOs into a Medicare Risk Contract.”. Inquiry. 1999;36(1):78–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porrell F, Wallack S. “Medicare Risk Contracting: Determinants of Market Entry.”. Health Care Financing Review. 1990;12(2):75–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossiter L. Understanding Medicare Managed Care. Chicago, IL: Health Administration Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Strunk B, Devers K, Hurley R. Health Plan–Provider Showdowns on the Rise. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change; 2001. Issue brief no. 40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]