Abstract

Objective

To determine how the capacity and viability of local health care safety nets changed over the last six years and to draw lessons from these changes.

Data Source

The first three rounds (May 1996 to March 2001) of Community Tracking Study site visits to 12 communities.

Study Design

Researchers visited the study communities every two years to interview leaders of local health care systems about changes in the organization, delivery, and financing of health care and the impact of these changes on people. For this analysis, we collected data on safety net capacity and viability through interviews with public and not-for-profit hospitals, community health centers, health departments, government officials, consumer advocates, academics, and others. We asked about the effects of market and policy changes on the safety net and how the safety net responded, as well as the impact of these changes on care for the low-income uninsured.

Principal Findings

The safety net in three-quarters of the communities was stable or improved by the end of the study period, leading to improved access to primary and preventive care for the low-income uninsured. Policy responses to pressures such as the Balanced Budget Act and Medicaid managed care, along with effective safety net strategies and supportive conditions, helped reinforce the safety net. However, the safety net in three sites deteriorated and access to specialty services remained inadequate across the 12 sites.

Conclusions

Despite pessimistic predictions and some notable exceptions, the health care safety net grew stronger over the past six years. Given considerable community variation, however, this analysis indicates that policymakers can apply a number of lessons from strong and improving safety nets to strengthen those that are weaker, particularly as the current economy poses new challenges.

Keywords: Safety net, low-income uninsured, charity care, uncompensated care, indigent care

The safety net provides health care to the nation's 20 million low-income uninsured residents1 regardless of their ability to pay for these services. While many providers care for some uninsured people, the safety net consists of the group of hospitals, community health centers and, in some cases, local health departments that provide the bulk of inpatient and outpatient care to this population. A strong safety net is vital for improving both individual health and public health. Given its reliance on external funding to finance care for the uninsured, however, the safety net is vulnerable to the vicissitudes of market and policy forces.

Numerous studies have documented the various pressures that challenged the safety net's ability to subsidize care for the uninsured2 during the 1990s and these studies generated pessimistic predictions for the future3. These pressures included the Balanced Budget Act (BBA), movement to Medicaid managed care, and welfare reform. The most comprehensive study of this time period, the 2000 Institute of Medicine report, found that the safety net was largely intact between 1997 and 1999 yet remained fragile. Pressures had not yet converged in all communities, however, and the study recommended ongoing analysis of the status of the safety net (Lewin and Altman 2000).

As part of the Community Tracking Study (CTS) site visit research, this analysis examines how market and policy pressures affected the safety net between 1996 and 2001, given the framework that safety net pressures and responses have varied effects due to underlying conditions in the community. This research builds off a baseline CTS safety net assessment (Baxter and Feldman 1999). While many safety net studies focus on a small set of providers or communities at a point in time, the CTS tracks the core safety net providers in 12 nationally representative communities over time. Such a qualitative approach is invaluable to understanding the safety net (Sofaer 1998), particularly due to the lack of quantitative data available (Baxter and Mechanic 1997; Felt-Lisk, McHugh, and Howell 2002).

We found that the safety net as a whole expanded and became more financially viable over the last six years. In this paper, we identify the major forces that contributed to stability and growth in the safety net, including policy responses to pressures and safety net strategies. We also explore the variation across communities and the importance of particular conditions to safety net strength. In addition, we discuss how changes in the safety net affected care for low-income uninsured people. Finally, we discuss the lessons to be learned on how to reinforce and further strengthen the safety net for the future.

Data and Methods

This research is part of the Community Tracking Study (CTS) site visits to 12 cities, conducted in two-year intervals (three rounds) between May 1996 and March 2001. In contrast to studies of cutting edge markets or those with particular problems, these communities were randomly selected to be nationally representative of urban areas (communities with more than 200,000 residents). A total of 1,690 interviews were conducted across three rounds with individuals from hospitals, physician groups, health plans, employers, and policymakers across a range of topics.4

For the safety net study, we interviewed more than 160 respondents each round from a variety of perspectives.5 In each site we interviewed the CEO or executive director of the core safety net providers—those that provide the largest proportions of charity care or for whom the uninsured represent a significant portion of patient mix. These included public hospitals, certain not-for-profit and for-profit hospitals, local health departments, and community health centers (CHCs).6 Among CHCs, we primarily focused on federally qualified or look-alike health centers, but also included any prominent free clinics. We identified providers through the Bureau of Primary Health Care at the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the National Association of Public Hospitals, as well as pre-site interviews with site respondents.

We also interviewed policymakers, including directors of state and local health agencies, elected officials or their staff, as well as safety net advocacy organizations. To gain a broader perspective of each community's safety net, we interviewed academics and newspaper reporters.

The majority of interviews were conducted in person using semistructured interview protocols. The interview questions focused on how the capacity and viability7 of the safety net had changed over the previous two years. We asked about the pressures (such as changes in policies and funding) on the safety net and how providers and policymakers responded to them. Specifically, we inquired about the strategies adopted to improve safety net capacity or viability. In addition, we asked how changes in the safety net affected access to care for the low-income uninsured.

Our findings reflect consistencies across the broad range of respondents in each study community. Researchers took detailed notes by hand during the interviews and typed up the notes after the interviews. They then coded the write-ups using ATLAS-ti qualitative software and wrote a research synthesis for the site. These sources served as the basis for this analysis. Triangulating our data helped confirm individual respondents’ assessments of the safety net and helped diminish other limitations, which included difficulties standardizing safety net capacity and access to services across sites.

We classified each site as having a strong or weak baseline capacity and viability. A strong safety net has an extensive, financially healthy network of safety net hospitals and outpatient providers relative to the demand for charity care services. Specific indicators of strength include the presence of financially viable public or private hospitals with adequate capacity and services for the uninsured, and sufficient outpatient facilities well distributed throughout the community. In addition, the uninsured are able to access most types of health care services. An example of a strong safety net was Boston, given its two major safety net hospitals and network of 25 community health centers for its relatively small uninsured population.

In contrast, a weak safety net is characterized by an inadequate number of struggling safety net hospitals and outpatient providers relative to demand for charity care. The uninsured face numerous barriers to basic health care services. An example of a weak safety net was Little Rock, given its financially vulnerable inpatient safety net provider and lack of CHCs, despite the high poverty and uninsurance in the area.8

Using the same factors that determined baseline strength or weakness, we also categorized each community as improved, stable, or deteriorated to indicate the general change in safety net strength between 1996 and 2001. We assigned each significant change in capacity or viability a score between –2 and +2, depending on whether the change was positive or negative and its significance. Scoring was contingent on the relative size of the safety net provider affected, relative amount of money involved or the potential number of uninsured individuals affected by the change. Two authors (Felland and Staiti) independently rated the key changes in each community.9 The net score for each community ranged from −3 to +5.5. We classified sites with scores between –1 and +1 stable, those with scores less than –1 deteriorated and those with scores greater than 1 improved.

Findings

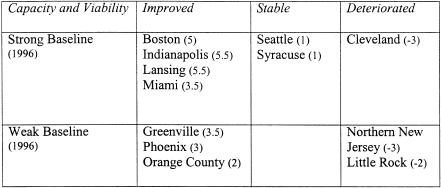

Three-quarters of the safety nets in our study sites were improved or stable over the six-year study period (Figure 1). Strong safety nets—such as Boston, Indianapolis, and Lansing—generally grew stronger and three historically weak safety nets—Greenville, Phoenix, and Orange County—also improved. Positive and negative changes balanced out in Seattle and Syracuse, resulting in stable positions. In the improved sites, capacity and viability of most core safety net hospitals and CHCs increased and access to preventive and primary care expanded.10

Figure 1.

A Snapshot of Safety Net Capacity and Viability Change, 1996—2001

Note: The number in parentheses after each site name refers to the net score to represent the degree of change in capacity and viability. In each community, the significant changes were assigned a score between –2 to +2, depending on whether the change was positive or negative and its relative significance. Scoring was contingent on the relative size of the provider, relative amount of money involved, or the potential number of uninsured individuals affected by the change. The net score for each community ranged from –3 to +5.5. We classified sites with scores between –1 and +1 stable, those with scores less than –1 deteriorated, and those with scores greater than 1 improved.

However, the safety net in one-quarter of sites deteriorated. The historically strong safety net in Cleveland suffered in the wake of two hospital closures, and the safety nets in New Jersey and Little Rock continued to struggle as their public hospitals faced financial difficulties.

Safety Net Pressures and Policy Responses

The expectations that various market and policy pressures would cause the entire safety net to deteriorate did not transpire. At the outset of our study, a number of pressures—including strained public budgets, the Balanced Budget Act (BBA) and Medicaid managed care—threatened to decrease the funding streams that safety net providers rely on to fund or cross-subsidize charity care. But by the end of the study period, targeted responses by federal, state, and local policymakers helped alleviate some negative effects in the stable and improved communities.

First, an improved economy created the foundation for such policy change. While constrained public budgets at the beginning of our study threatened to reduce funds available to the safety net (Fishman and Bentley 1997), the economy actually boomed from the late 1990s to 2001, creating federal, state, and sometimes local budget surpluses. These gains allowed policymakers to raise direct and indirect safety net funding, such as HRSA's increases in CHC grants and new Community Access Program (CAP) grants to improve safety net infrastructure. A number of safety nets received additional funds from the state and some obtained modest gains from city or county revenues. In addition, many safety nets benefited from increased contributions from private foundations.

Second, the 1997 Balanced Budget Act (BBA) cuts to Medicaid disproportionate share hospital (DSH) funds did not seriously affect all safety net providers. Rather, some states responded by drawing additional federal dollars within the allowable cap or changing how they allocated funds to raise DSH payments to these providers. Plus, federal lawmakers reduced some of the future DSH cuts through the 1999 Balanced Budget Refinement Act (BBRA). In addition, although the BBA repealed minimum payment guarantees for providers, a number of states retained cost-based reimbursement for community health centers.

Third, reductions in Medicaid revenues due to states’ move to managed care were not as severe as anticipated for safety net providers. For example, many states responded with modest payment increases to plans during the study period. Plus, some community health centers that received capitated Medicaid payments identified benefits of the steady revenue stream.

In addition, concerns that managed care would hurt safety net providers by transferring most Medicaid beneficiaries into commercial health plans and their provider networks were not realized. Rather, efforts by state and local policymakers to promote safety net provider participation in public insurance programs mitigated such competition. For example, Medicaid agencies in three sites gave preferential treatment in contracting negotiations to health plans that included safety net providers in their networks. Also, relatively low rates to plans led to fewer mainstream providers participating in Medicaid networks than expected. By the end of the study period, most safety net providers in our study sites reported stable or increased proportions of Medicaid and State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) patients.

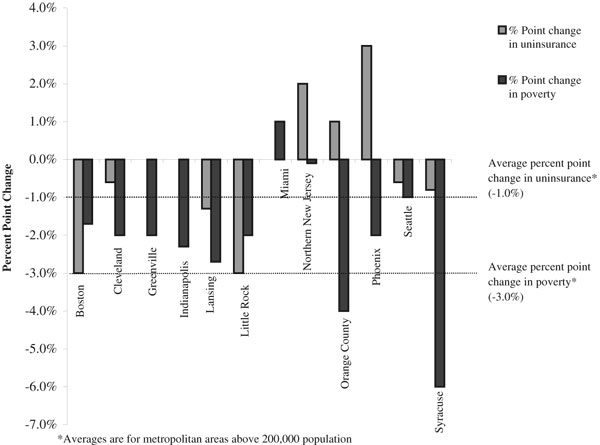

Indeed, federal enactment of SCHIP in 1997 benefited safety net providers by providing insurance payments for previously uninsured patients and helped contain the growing demand for charity care. Uninsurance was on the rise in 1996 due to declines in private and public coverage (Lewin and Altman 2000). However, streamlined application processes and aggressive community out-reach efforts stimulated enrollment in both SCHIP and Medicaid, particularly after declines in Medicaid enrollment due to welfare reform (Felland and Benoit 2001). By the end of the study period, expansions in public coverage and the economy contributed to declines in uninsurance and poverty rates—approximations of demand for charity care—in most CTS communities (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Changes in Poverty and Uninsurance in CTS Sites, 1996–1997 to 2000–2001

Source: The CTS Household Survey weighted estimates of the nonelderly (under age 65) population. Due to small site-level sample sizes, we are unable to provide estimates of the percent of low-income individuals who are uninsured in each site. Instead, the percent uninsured and the percent below poverty are used here as approximate indicators of demand for indigent care. The Household Survey estimates that 33.3 percent of individuals with family incomes below the federal poverty level across all metropolitan areas (those with 200,000 or more residents) were uninsured in 2000–2001.

Safety Net Strategies

Safety net providers in the stable and improved communities also adapted to market and policy pressures with strategies that enhanced their ability to care for the uninsured by improving financial viability and expanding capacity.11

Financial Management Strategies

One of the key ways safety net providers strengthened their financial viability was to implement strategies that focused on improving efficiencies and increasing direct and indirect revenues to support charity care. First, most safety net providers streamlined their operations to contain costs and increase revenues. Some providers cut staff, shared administrative functions with other providers, and reorganized operational processes to improve their ability to collect payment for services from individuals and third parties.

Second, some safety net providers integrated horizontally. In particular, a few safety net hospitals merged with other hospitals to expand their financial resources. Although mergers of safety net hospitals with other hospitals often generate community concern that the new entity will reduce its focus on the uninsured, mergers in our sites generally strengthened the safety net.

Third, most safety net providers increased their attention to insured patients in order to generate revenues that help cross-subsidize uncompensated care. For instance, safety net hospitals made ardent efforts to attract both commercially and publicly insured patients, and community health centers focused on those covered by Medicaid and SCHIP. Virtually every safety net provider in our study intensified outreach activities during the study period to help enroll uninsured patients in such programs.

In addition, safety net hospitals or groups of community health centers in six sites pursued vertical integration by purchasing or affiliating with health plans to retain more Medicaid enrollees and dollars. Finally, safety net leaders also lobbied for increases in charity care funding from all levels of government and private foundations.

Strategies to Improve Capacity

Safety net providers also focused on strategies to expand their capacity and improve access to care for the uninsured. First, many safety nets expanded their facilities and services. For instance, providers and communities built new health centers and existing centers and hospitals added outpatient facilities, primarily for primary and preventive services. Furthermore, many providers extended their days and hours of operation and added services, such as specialty, interpreter, and other social services. In many cases, enhanced funding facilitated these efforts.

Second, some communities worked to extend and support the pool of providers to care for the uninsured. In particular, these efforts focused on improving access for certain geographic areas, populations, and services. This generally involved the core safety net hospital distributing a portion of its charity care pool funds to providers and practitioners that either did not generally treat the uninsured, or to smaller safety net providers that needed assistance to increase capacity.

Expanding the pool of providers was part of a third strategy—to encourage the uninsured to seek more primary and preventive care and reduce reliance on emergency departments. For example, policymakers and providers collaborated in some sites to develop managed care programs for the uninsured through funding from existing charity care pools. The core safety net hospital or local health agency administered these programs through a network of primary and specialty providers, reimbursing them for services they generally were not compensated for in the past (Felland and Lesser 2000). The three established programs in the CTS sites expanded enrollment and provider participation during the study period.

Community Variation

While most safety nets experienced common pressures and often responded in similar ways, there was considerable variation across communities. A number of factors culminated in safety net deterioration in three CTS sites. These safety nets encountered more problems from pressures, such as Medicaid managed care and the BBA, than their stable and improved counterparts. In addition, provider efforts to implement strategies to improve their situation were often impeded by market forces, particularly intense competition for insured patients. Without adequate funding to reinforce safety net providers, viability and capacity declined in these communities.

Indeed, we found the presence of three conditions critical in bolstering the safety net—community support, strong leadership, and adequate funding.12 These conditions were generally associated with the political culture and wealth of the community and the state. However, our longitudinal study showed that these conditions are not static and can vary significantly over time.

Although the first condition, community support, is often entrenched in the history and culture of a community, we found that certain influences can boost concern for the uninsured. For instance, attention to the safety net in Greenville increased dramatically during the study period. An early CTS report of a weak and limited safety net prompted an assessment of community needs and motivated foundations and hospitals to increase their contributions to the safety net, leading to CHC expansions in that community.

Second, we found that adverse events often led to enhancements in safety net leadership. In Cleveland, for example, local, state, and federal policymakers became actively involved as two safety net hospitals were in the process of closing during our most recent round of site visits. These closures created gaps in health care access for the uninsured and contributed to increased charity care and financial losses for the county hospital. These concerns galvanized community leaders to collaborate on ways to improve access to preventive and primary care and reduce reliance on emergency departments.

Finally, while strong and improved safety nets benefited from adequate external funding from DSH dollars and state or local charity care pools, new funding sources also boosted safety net strength. By the end of the study period, some communities gained access to tobacco settlement and tax dollars. For instance, the viability of safety net providers in Phoenix improved with the help of tobacco tax revenues, and the capacity of hospitals and community health centers in Orange County will expand with tobacco tax and settlement funds.

The evidence that supportive conditions can be cultivated in a community provides optimism that sites that deteriorated over the last six years can improve in the future. For example, safety net leadership may help Cleveland's safety net regain its strength by our next round of site visits. Such gains will likely be more difficult for northern New Jersey and Little Rock—safety nets that started from a weak base and continued to deteriorate over the study period.

Impact of Safety Net Changes on the Uninsured

The net effect of changes in the safety net was generally positive for uninsured people. Respondents in the improved and stable sites reported that access to primary and preventive care for the uninsured increased over the last six years due to the opening or expansion of hospital clinics and CHCs and efforts to link the uninsured to a medical home. Managed care programs for the uninsured reportedly reduced inpatient length-of-stay and emergency department utilization among enrollees.

While efforts to enhance access to specialty care also intensified, respondents across sites reported that access to most specialty care services remained largely inadequate. Identifying specialty practitioners—particularly for mental health and dental care—to serve the uninsured proved difficult. Indeed, recent CTS survey results reported that individual physicians reduced the amount of charity care they provided over the last few years (Reed, Cunningham, and Stoddard 2001).

In addition, some physical barriers to safety net providers persisted. This was a particular problem in communities in which providers were not located where most of the uninsured lived, if the uninsured lived in a wide geographic area, or if specialty services were offered at only a few facilities. While some respondents expressed concern that provider efforts to implement cost-sharing or reduce staff could impede access to care, there were few reports in the sites that this was a significant problem.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that the nation's safety net survived various pressures and even grew stronger over the last six years. Most communities were able to mitigate the effects of challenging market and policy fluctuations and reinforce their safety net to improve access to services for low-income uninsured people.

The safety net benefited from a strong economy and efforts to protect its funding from various pressures. Policymakers made adjustments to some policies, such as the BBA, and tried to support safety net providers as they adapted to Medicaid managed care. In addition, safety net providers implemented strategies to boost cross-subsidies for charity care, such as attracting insured patients.

However, there was variation across communities in how the safety net changed over the last six years. Safety nets that were stable or that improved exhibited supportive conditions, including community concern for the uninsured, strong policy and organizational leadership, as well as adequate funding to help meet demand for services. Communities that deteriorated lacked many of these factors, particularly sufficient funding, and faced other pressures, such as intense competition.

The resilient safety nets provide lessons on how to strengthen their more vulnerable counterparts. Policymakers can focus their efforts on the weak areas to cultivate supportive conditions and select strategies to best accommodate a community's unique characteristics. For example, collaboration in some communities has helped leverage existing funds to create programs that coordinate care for the uninsured. Yet, safety nets that are historically weak may require additional funding and leadership.

Furthermore, even relatively strong safety nets require additional assistance. Particular focus should be placed on persistent problems, such as inadequate access to specialty care. Given the safety net's susceptibility to market and policy forces, longer-term reinforcements should be explored as well.

Concerns about the resilience of the safety net again loom large given the current economic slowdown. Increasing unemployment and rising insurance premiums likely will lead to increases in the number of uninsured, while federal and state revenue shortfalls could reduce public coverage and threaten subsidies for the safety net, particularly the distribution of tobacco-related funds.

In addition, there are indications that the push-and-pull of safety net policy continues. For example, the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services is phasing out the Medicaid loophole that allows states to draw down supplemental federal Medicaid and DSH dollars to support safety net services. On the other hand, President Bush supports expanding community health center capacity, and federal funding for FQHCs increased by approximately 12 percent for fiscal year 2002.

The net effect of these pressures and policy responses on the safety net remains to be seen. The way each community responds likely will play a prominent role in shaping the outcomes. The more policymakers, local leaders, and foundations can do to promote beneficial strategies and conditions and target these efforts where there is greatest need, the more effective communities will be in weathering the challenges in the years ahead.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lawrence Brown, Ph.D., of Columbia University for his contributions to the study design and data syntheses for this paper.

Note

Community Tracking Study, 2000–2001 Household Survey.

In this paper we use the terms charity care, uncompensated care, and care for the uninsured interchangeably.

These studies include: Lewin and Altman 2000; Felt-Lisk, McHugh, and Howell 2001; Brennan, Guterman, and Zuckerman 2001; Zuckerman et al. 2001; Meyer, Legnini, and Waldman 1999; Fagnani et al. 2000; Baxter and Feldman 1999.

For an overview of the entire Community Tracking Study project, please see the Methods section of the paper by Lesser, Ginsburg, and Devers 2001.

We interviewed an average of 13 respondents in each safety net, although we generally interviewed fewer in the smaller sites and more in the larger communities.

We use the term “community health center” and the acronym “CHC” as an umbrella term for all types of centers that focus on low-income uninsured populations—federally-qualified, free clinics, and other local health centers, such as those operated by hospitals.

Capacity refers to the supply of health care services for the low-income uninsured population. Significant changes in capacity included openings or closures of facilities, and expansions or contractions in services provided, changes in geographic service area or hours of operation. Viability refers to the financial health of safety net providers, which is an indicator of the safety net's ability to serve the uninsured in the future. Significant changes in viability include changes in funding levels and financial losses or gains.

A community lacking a public hospital or other safety net hospital or federally-qualified health centers is not automatically deemed weak if mainstream hospitals and other health centers or health departments provide sufficient inpatient and outpatient safety net capacity.

The authors agreed on the scores for most changes, although there were some slight differences. To account for this, the average of the two scores was used to calculate the final site score. As a result, some site scores are not whole numbers.

Most local health departments, with the exception of those in Lansing and Seattle, reduced their provision of direct medical services during this period. As they returned to traditional public health functions, health departments shifted direct patient services to other providers. However, because health departments generally were not major safety net providers before this shift, their change in focus did not significantly affect the status of the safety net in most communities.

Many of these strategies have been identified in other studies as well (Lewin and Altman 2000; Felt-Lisk, McHugh, and Howell 2001; Brennan, Guterman, and Zuckerman 2001; Norton and Lipson 1998).

Other studies also have identified the benefits of these conditions (Ormond and Lutzky 2001; Lewin and Altman 2000; Meyer, Legnini, and Waldman 1999; Felt-Lisk, McHugh, and Howell 2001; Brennan, Guterman, and Zuckerman 2001).

This research was conducted at the Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, DC, with funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

REFERENCES

- Baxter RJ, Feldman RL. Staying in the Game: Health System Change Challenges for the Poor. Washington, DC: The Center for Studying Health System Change; 1999. Research report. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter RJ, Mechanic RE. “The Status of Local Health Care Safety Nets.”. Health Affairs. 1997;16(4):7–23. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.4.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan N, Guterman S, Zuckerman S. Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2001. The Health Care Safety Net: An Overview of Hospitals in Five Markets and companion piece How Are Safety Net Hospitals Responding to Health Care Financing Changes. [Google Scholar]

- Fagnani L, Singer I, Cordova M, Carrier B. Washington, DC: National Association of Public Hospitals and Health Systems; 2000. America's Safety Net Hospitals and Health Systems: Results of the 1998 Annual NAPH Member Survey. [Google Scholar]

- Felland LE, Benoit AM. Communities Play Key Role in Extending Public Health Insurance to Children. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change; 2001. Issue brief no. 44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felland LE, Lesser CS. Local Innovations Provide Managed Care for the Uninsured. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change; 2000. Issue brief no. 25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felt-Lisk S, McHugh M, Howell E. “Monitoring Local Safety Net Providers: Do They Have Adequate Capacity?”. Health Affairs. 2002;21(5):277–83. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman LE, Bentley JD. “The Evolution of Support for Safety-Net Hospitals.”. Health Affairs. 1997;16(4):30–47. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.4.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesser CS, Ginsburg P, Devers K. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change; 2001. Under Review. “The End of an Era: What Became of the ‘Managed Care Revolution’ in 2001?”. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin ME, Altman S. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2000. “America's Health Care Safety Net: Intact but Endangered.”. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JA, Legnini MW, Waldman EK. Washington, DC: Economic and Social Research Institute; 1999. “Current Policy Issues Affecting Safety Net Providers.”. [Google Scholar]

- Norton SA, Lipson DJ. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 1998. Public Policy, Market Forces, and the Viability of Safety Net Providers. Occasional paper no. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Ormond BA, Lutzky A Westpfahl. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 2001. “Ambulatory Care for the Urban Poor: Structure, Financing, and System Stability.”. [Google Scholar]

- Reed MC, Cunningham PJ, Stoddard J. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change; 2001. “Physicians Pulling Back from Charity Care.”. Issue brief no. 42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofaer S. “Qualitative Methods: What Are They and Why Use Them?”. Health Services Research. 1998;34(5):1101–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman S, Bazzoli G, Davidoff A, LoSasso A. “How Did Safety Net Hospitals Cope in the 1990s?”. Health Affairs. 2001;20(4):159–68. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.4.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]