Abstract

Objective

To conduct site visits to study the early experiences of firms offering consumer-driven health care (CDHC) plans to their employees and firms that provide CDHC products.

Data Sources/Study Setting

A convenience sample of three firms offering CDHC products to their employees, one of which is also a large insurer, and one firm offering an early CDHC product to employers.

Study Design

We conducted onsite interviews of four companies during the spring and summer of 2003. These four cases were not selected randomly. We contacted organizations that already had a consumer-driven plan in place by January 2002 so as to provide a complete year's worth of experience with CDHC.

Principal Findings

The experience of the companies we visited indicated that favorable selection tends to result when a CDHC plan is introduced alongside traditional preferred provider organization (PPO) and health maintenance organization (HMO) plan offerings. Two sites demonstrated substantial cost-savings. Our case studies also indicate that the more mundane aspects of health care benefits are still crucial under CDHC. The size of the provider network accessible through the CDHC plan was critical, as was the role of premium contributions in the benefit design. Also, companies highlighted the importance of educating employees about new CDHC products: employees who understood the product were more likely to enroll.

Conclusions

Our site visits suggest the peril (risk selection) and the promise (cost savings) of CDHC. At this point there is still far more that we do not know about CDHC than we do know. Little is known about the extent to which CDHC changes people's behavior, the extent to which quality of care is affected by CDHC, and whether web-based information and tools actually make patients become better consumers.

Keywords: Employer-sponsored health insurance, health reimbursement arrangement, cost sharing

Consumer-driven health care (CDHC) has been touted as the salvation of our health care system (Herzlinger forthcoming)—or as the hastening of its demise (Shuit 2003). Proponents point to facets that promote greater choice among health plans and consumer involvement in cost control, whereas opponents fear it will destabilize the risk pool and result in people forgoing needed services. Until now, analyses have been based more on opinion than fact (see, for example, Gabel, Lo Sasso, and Rice 2002; and Gabel and Rice 2003). This is understandable, however, given the newness of these health plans—there have been few objective data analyses conducted because of the lack of available evidence. Unfortunately, the “big” questions remain not only unanswered, but also infused with ideology. For example, little is known about the extent to which CDHC changes enrollees' behavior, the extent to which quality of care is affected by CDHC, and whether web-based information and tools actually make patients become better consumers.

This issue of Health Services Research provides some of the first published data-driven evidence on the impact of consumer-driven products, which has the potential to begin to move the debate away from ideology into the realm of empirical evidence. In this article we present four case studies that were conducted through in-person site visits by one or more of the authors. We conducted the site visits during the spring and summer of 2003. We interviewed benefit directors at all companies, in addition to CEOs, chief actuaries, and human resources personnel at some of the companies. We spoke only with company personnel in order to get an unbiased sense of their experiences with CDHC; that is, not colored by the views of the health plans'. These four cases were not selected randomly. Rather, we contacted organizations that already had a consumer-driven plan in place by January 2002 so as to provide a complete year's worth of experience with CDHC.

Furthermore, we sought cooperation from firms that provided a cross-section of products. Humana is a health insurer and employer that offers its own consumer-driven product to its employees. Countrywide Financial and Woodward Governor represent, respectively, financial and manufacturing firms that offer a Definity Health product. Although we sought other companies that offered health reimbursement arrangement (HRA) plans, Definity was the only one that had employer clients accessible to us that dated back to the beginning of 2002. Patient Choice represents a Minnesota-based consumer-driven approach to health care that actually predates what is commonly thought of today as consumer-driven health care. Patient Choice's model differs quite significantly from the HRA-style plans offered by Definity and a number of its competitors. We include Patient Choice among our case studies because its longer lifespan provides important insights into the role of consumer and provider decision making on health care costs. Moreover, we include Patient Choice because it is not clear that the market has made a final determination of what the dominant model of CDHC will be in the future.

In reviewing the case studies that follow, several points should be kept in mind:

The firms were willing to have their experiences examined and published. Accordingly, they are more likely to have had positive experiences than other firms.

The data tabulations shown were provided by the firms; the scope of the project did not allow use to collect or analyze claims data.

The findings presented represent, in most cases, just one year's worth of experience.

Case studies, by their nature, provide descriptive data about which any generalizations should be made with extreme caution.

Countrywide Financial Corporation

Background

Countrywide Financial Corporation, founded in 1969, specializes in mortgage lending but in recent years has diversified into related areas such as insurance and banking. In the 12-month period ending September 2003, revenues exceeded $7.5 billion with net earnings of more than $2 billion. Its corporate headquarters are located in Southern California. Countrywide has offices nationwide, with just over half of its employees in California. The company has been growing quickly due to its diversification efforts as well as the boom in mortgage financing.

Countrywide offers its employees a menu of health plans that includes both preferred provider organization (PPO) and point-of-service (POS) plans sponsored by Cigna, a variety of health maintenance organizations (HMOs) (with Cigna being the main choice in California), and a consumer-driven health plan sponsored by Definity Health. In 2002, the monthly employee out-of-pocket costs for the Cigna HMO were $42. The Definity and POS plans both cost $88 with the PPO costing $126. These differences reflect both variation in total costs as well as a differential subsidization policy on part of the company, which provides the greatest subsidy to HMO coverage and the lowest to the PPO. During the site visit, Countrywide reported that it subsidizes HMO coverage the most because it is least expensive and because the company does not experience as much risk because, unlike its other health plans, the HMO is a fully insured product.

Definity Health was first offered to Countrywide employees in January 2002. Unlike the case of many other firms, the antecedent was not so much rising corporate health care costs or the backlash against HMOs. Rather, it was primarily the availability of physicians. In one of its main southern California locations, a bankruptcy in a local physician group, coupled with a perception that some of the other medical groups in the area were no longer accepting HMO patients, led to concern that Countrywide employees might have been having difficulties securing medical care. Management decided to provide another choice to the menu of plans, but sought something that could have cost-savings potential like HMOs but choice of providers like PPOs. Before contracting with Definity, it arranged two focus groups, one of senior managers who worked with staff on benefit issues, and the other of a cross-section of employees. After having the Definity plan explained to them, most reportedly reacted very positively. Attractive features included: a wide network of physicians; a personal care account that provided first-dollar coverage; the relatively small “donut hole” (explained below); and the fact that they would have another health plan choice.

Benefits personnel were concerned about outreach since many Countrywide employees are in branch offices far from the corporate headquarters. To deal with this, they sent both written materials and videos to their offices around the country. This was supplemented by employee meetings at the major locations as well as seminars designed to explain the plan to managers. Enrollment is conducted online, and a variety of other online resources are available. Employees can keep track of their HRA through the Definity website, which is available from Countrywide's website.

Experience

Enrollment in Definity is low and growing slowly. When it was first offered in January 2002, 2 percent of the roughly 23,000 eligible California-based employees participating in the company's health plans chose Definity. This had doubled to nearly 4 percent during the January 2003 open enrollment period. Comparing enrollment in December 2002 to January 2003, 90 percent of Definity members reenrolled in the plan.

In 2003, individuals who choose Definity receive a $1,000 personal care account (PCA). All covered health care expenses that are incurred are automatically drawn from this account until it is exhausted. The annual deductible is $1,500, so individuals face a $500 “donut hole” before they are eligible for major medical coverage. At that point, in-network services are covered at an 80 percent rate, and out-of-network services, 60 percent. There is an annual out-of-pocket maximum of $2,500 for in-network services and $3,000 for out-of-network. Those with family coverage receive a $2,000 PCA, have a $3,000 deductible leaving a $1,000 donut hole, and have an annual out-of-pocket maximum of $5,000 for in-network services and $9,000 for out-of-network.

Generic prescription drugs are reimbursed at the same percentages (80 percent and 60 percent depending on whether a network pharmacy is used), but for brand name drugs the patient must also pay the difference between the brand name and generic costs. The plan also covers an annual physical exam at no cost to the patient so long as a network physician is used.

Analysis

Countrywide provided some data on selection as well as the use of the PCA. We compared enrollment in Definity versus all other plans with respect to three variables: gender, type of coverage (e.g., individual, family), and income (Table 1). Men are more likely than women to choose Definity, with 4.8 percent of men doing so compared to 3.6 percent of women. Those with family coverage (employee plus one or more dependents) are slightly more likely to choose Definity than those with individual coverage: 4.4 percent versus 3.8 percent. Perhaps the most interesting finding concerns income. Employees are divided into two groups: those with base salaries of $80,000 or more (14 percent) and those who earn less (86 percent). Employees with higher salaries are nearly twice as likely to enroll in Definity: 6.4 percent versus 3.7 percent.

Table 1.

Enrollment of Countrywide Employees into Definity versus Other Plans, 2003

| Definity | Other Plans | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 4.1% | 95.9% |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 4.8 | 95.2 |

| Female | 3.6 | 96.4 |

| Coverage Type | ||

| Individual | 3.8 | 96.2 |

| Family | 4.4 | 95.6 |

| Income | ||

| $80,000 or more | 6.4 | 93.6 |

| Less than $80,000 | 3.7 | 96.3 |

Data are not available to indicate whether the high-income people are healthier or sicker than others. On the one hand, income tends to be positively correlated with health status, but on the other hand, those with higher incomes are also likely to be older. One possible explanation for more higher-income employees choosing Definity relates to the employee premium requirements. Because employees pay more than twice as much for Definity than for the Cigna HMO, one would expect higher-paid employees to be more able to afford this option. It is also possible that higher-income persons are less likely to be concerned with the “donut hole.” In addition, such individuals, who have positions of higher responsibility in the firm, tend to be more accustomed to making the types of financial decisions one needs to make in a consumer-driven plan.

Definity also provided data on use of the PCAs. Just less than half (46 percent) of enrollees used their entire PCA in 2002. Others were eligible for rollover if they stayed with the plan. Somewhat surprisingly, those who left the Definity plan used slightly less of the money in their accounts, and thus would have been able to roll over more had they remained with the plan in 2002. Those not renewing used up 69 percent of the PCA, compared to 73 percent for those who stayed with Definity.

Finally, data on the use of the PCA by month in 2002 shows a distinct U-shaped pattern. Enrollees draw heavily on their PCA in the first three months of the year—not surprising since some may have waited until January to obtain services, and because the accounts have more money from which to draw early in the year before medical expenses climb. Over the next several months PCA payments are lower but fairly flat, and there is a significant upsurge in November and December. To illustrate, 60 percent more money was drawn out of PCAs in December than in October; in fact, more was drawn in December than in any other month. This demonstrates that many Definity members felt the need to use up their accounts, which is surprising since the 90 percent reenrolled and therefore were eligible to rollover any remaining monies.

Assessment

Countrywide has not conducted surveys of its employees to elicit satisfaction with the Definity plan. The fact that almost all of those enrolled in December 2002 chose the plan again in January 2003—when HMO, POS, and PPO plans were available—provides an indication of general satisfaction on the part of enrollees. Benefits personnel reported to us that they have been very pleased with the experience so far, and that customer service has been “exceptional.” Offering the plan has not entailed much in the way of additional administrative effort. But with only 4 percent of employees choosing the plan after it had been in place for a year, it does not appeal to everyone. If the plan does become more than a niche player in coming years, management will need to further study enrollment patterns to determine the plan's effects not only on its own enrollees, but on the risk pool faced by the other health plans available to Countrywide employees.

Woodward Governor

Background

Woodward Governor is a company that designs, manufactures, and services energy control systems and components for aircraft and industrial engines and turbines. Their products and services are used in power generation, process industries, transportation, and aerospace markets. Woodward has a long history of being a self-described paternalistic employer. The firm has historically offered generous benefits for retirement coverage and other fringe benefits. As recently as four years ago, for example, employees were not required to contribute to their health insurance premium. Woodward employs approximately 2,600 workers at two major work sites: Rockford, Illinois (its corporate headquarters) and Colorado, though the company also has smaller groups of employees in South Carolina, Buffalo, New York, and Michigan. As a manufacturing firm, the company's employees are 75–80 percent male. Woodward has a nonunionized workforce.

Woodward's health benefit costs were increasing at a rate of 16 to 19 percent per year—a rate of increase that was thought by management to be untenable, particularly during a period of increasing competitive threats from abroad. This cost trend motivated the company to begin considering other health insurance options. The director of corporate benefits learned of Definity Health and recognized the congruence of Definity's model to Woodward's desires. Definity's model validated the company's idea and the director of benefits championed the idea to Woodward management. The company indicated that the goal of the effort was not cost-shifting to workers, but a genuine desire to create better incentives so that employer and employee could together “shrink the size of the health care pie.”

Experience

In January 2002 at the Rockford, Illinois, worksite, Woodward began offering the Definity HRA alongside a PPO option that had been previously offered to employees. Interestingly, the director of benefits and Woodward's CEO believed that the Definity model would be more efficacious in a total replacement setting than as an add-on. However, because Definity only contracted with one of three local hospital-based provider networks, many of the providers available to employees in the PPO were not available to employees. Thus, to avoid controversy among employees it opted to implement Definity as an add-on. By 2003 Definity had contracted with a second provider network. Perhaps as a consequence of this network change, Definity enrollment increased substantially in the Rockford market in 2003.

The Definity options came in two varieties: a higher- and a lower-deductible plan. Option 1 included a $1,000 PCA and a $1,500 deductible for single coverage ($500 donut hole), and $2,000 PCA and a $3,000 deductible for family coverage ($1,000 donut hole). Option 2 included a $1,000 PCA and a $2,000 deductible for single coverage, and $2,000 PCA and a $4,000 deductible for family coverage. Only one employee enrolled in the higher-deductible option. Premium contributions for the Definity plans were $4/$30 (single/family) biweekly for Option 1 and $3/$25 (single/family) biweekly for Option 2. After reaching the deductible, all allowable in-network care services were covered at 100 percent. Out-of-network services were covered at 80 percent. The PPO options were $8/$60 (single/family) biweekly. One important change that was also implemented beginning in January 2002 was an increase in cost sharing for pharmacy benefits under the PPOs: the flat $5 copayment was replaced with 15 percent coinsurance on pharmaceuticals. By contrast, under Definity, pharmaceuticals, like all other health care services, are paid out of the PCA at 100 percent, then completely out of pocket in the donut hole, and again at 100 percent once the deductible is reached.

The company had 12 percent enrollment in the Definity product in 2002, which was generally greater than the initial enrollment levels observed at other companies offering Definity. However, it is unclear the extent to which the pharmacy benefit change in the PPO option caused employees to enroll in Definity. Benefits personnel believed that the increase pharmaceutical cost sharing was at least partly responsible for the relatively high interest in the Definity option. Company benefit personnel stated that the principal impediment in the launching of the plan was getting employees to understand how Definity worked. Employees were not accustomed to first having first-dollar coverage and then subsequently facing out-of-pocket costs via the deductible. Definity employees provided onsite sessions to explain the product to employees during open enrollment. The sessions were believed to be helpful in swaying the employees who attended them.

Data

Definity enrollees in Rockford in 2002 were demographically similar to non-Definity enrollees in terms of age and gender. Benefits personnel pointed out that two diabetics were among the 195 employees who enrolled in the Definity plan, which would appear to suggest that enrollment was not comprised exclusively of healthy persons. Still, health care expenditures for Definity enrollees for the 2002 calendar year were roughly half that of PPO enrollees ($1,492 versus $2,837). It is doubtful that the Definity plan cut health care expenditures by 50 percent, but the company was unable to provide us with 2001 expenditures for each group from which to get a rough estimate of the extent to which Definity enrollees experienced a change in their expenditures as a result of enrollment in the Definity product. Just under 40 percent of Definity enrollees spent through their PCAs. Of those who spent through their PCAs, roughly three-quarters also spent through their deductibles. Approximately 15 percent of the Definity enrollees had total health care expenditures in excess of $5,000. Satisfaction surveys conducted by Definity indicated satisfaction with the plan to be in excess of 90 percent.

Assessment and Future Directions

Benefits personnel at Woodward indicated that they were pleased with the degree of customer support provided by Definity, though some concern was expressed as to whether the level of support would continue as Definity continues to expand to other employers. In addition, because of the large number of subcontractors Definity used at the time, when there were problems, it was often a time-consuming process to sort out. In general, though, human resource personnel found the administrative burden “much less” for Definity enrollees relative to PPO enrollees, though this could be related to the lower levels of utilization incurred by Definity enrollees.

Beginning in 2003, the company continued to offer Definity as an add-on option in the Rockford market, but also implemented Definity as a total replacement product in its Colorado market. In Colorado, Definity was able to contract with the same provider network that was offered to employees through their PPO in previous years. However, the company reported that after it was announced in October of 2002 that all employees were facing a mandatory switch to Definity in January 2003, the Colorado-based employee group exhibited a pronounced increased in what benefits personnel termed “elective” procedures in the remaining three months of the year. Benefits personnel reported that the company witnessed “two years worth of elective procedures in three months.” Commonly cited examples included knee and back operations that were not life threatening and could have been relatively easily postponed. Consequently, pre–post comparisons in the Colorado market (which are not possible at this time) are likely to be clouded by this surge in elective procedures as employees anticipated the new health insurance benefit.

Woodward continued to offer Definity as an add-on option in Rockford and Definity enrollment increased to 25 percent in 2003, perhaps as a consequence of the aforementioned increased size of the Rockford provider network. Only nine employees who had previously enrolled in the Definity plan in 2002 did not reenroll in 2003. Employee premium shares were increased to $6/$35 (single/family) biweekly in Option 1 and $5/$30 (single/family) biweekly in Option 2; the structure of the PCA and deductible was maintained. The PPO premium shares in the Rockford market also increased to $9/$66 (single/family) biweekly. At this time the company plans in 2004 to continue offering Definity as an add-on option in Rockford and as a full-replacement product in Colorado. The company continues to believe that health care expenditures will be better controlled over the longer term by continued use of CDHC products.

Humana

Background

Humana Inc., one of the nation's largest insurers, was the site of an early experiment with CDHC. The Louisville-based insurer covers approximately 6.6 million Americans in 18 states including 1.8 million PPO enrollees and 1.2 commercial HMO enrollees. In July 2001, Humana launched their CDHC product “SmartSuite” at its Louisville headquarters with their 4,800 employees and 5,000 dependents as an experimental group.

Humana CEO Mike McCallister described Humana's decision to offer CDHC products, as follows. “We had tried every means for controlling costs except getting consumers involved. We ultimately determined that the solution must involve four factors: (1) greater consumer choice; (2) putting more consumer dollars at stake; (3) improved technology; and (4) a recognition that employees were over insured” (personal communication March 12, 2003).

In another article in this issue, Laura Tollen and Murry Ross describe in greater detail Humana's changes in their health benefits for their Louisville employees. Here we highlight changes in the benefit design the year prior and the first year of adopting SmartSuite.

Prior to adoption of SmartSuite, Humana offered its Louisville workers two PPO plans and one HMO plan. Humana contributed 79 percent of the monthly premium cost of coverage. SmartSuite consisted of five plans offered to Humana employees—two PPOs, an HMO plan, and two HRA-like plans, termed “Coverage First.” Humana contributed a fixed amount set at a level less than the lowest-cost plan (an HRA-type plan). Coverage First was not technically an HRA plan because employees could not carry over unspent money in the personal spending account at the end of the year.

Covered benefits and provider networks in the traditional HMO and PPO plans and Coverage First were identical, but cost-sharing requirements differed. In the standard PPO and HMO plans, Humana imposed copayments for hospital stays of $100 per day, increased copayments for prescription drugs, and raised out-of-pocket catastrophic thresholds in the PPO plans. One PPO plan added a tiered hospital benefit. Prescription drugs and mental health benefits were carved out. Coverage First had a $500 use-or-lose spending account that included copayments where allowances must be spent within network. One Coverage First plan had a deductible of $1,000, and another additional deductible of $2,000.

Enrollment in SmartSuite is 100 percent electronic, with software to guide employees' plan selection. To control for potential risk selection, Humana used partial risk rating, thereby raising the employee contribution rate for Coverage First and lowering employee contributions for the HMO and PPO plans. Monthly employee contributions in the first year of SmartSuite for the HMO plan were $39, $44 for the richest PPO plan, and $13 for the Coverage First plan. Humana changed the contribution formula to discourage “double coverage” in the employee's and spouse's health plans.

Experience

During the first year of SmartSuite, 6 percent of covered workers chose Coverage First (Table 2). In general, as employees faced greater contributions for selecting higher-cost plans, they moved “downstream” to plans with greater cost sharing. In the second year of SmartSuite, enrollment was extended to non-Louisville employees. Differences in the employee contribution rate between Coverage First and the traditional HMO and PPO plans grew to more than $50 per month, and consequently, Coverage First captured 21 percent of the non-Louisville Humana employee market share. Preferred provider organization plans suffered the major loss in market share.

Table 2.

Summary of Premiums and Enrollment in Before and After Humana SmartSuite Introduction for Humana Louisville and Non-Louisville Employees

| Humana Louisville 2001–2002 | Humana Non-Louisville 2002–2003 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly Single Contribution | Enrollment | Monthly Single Contribution | Enrollment | |

| Prior Plan HMO | $39 | 39% | $43 | 45% |

| Prior Plan PPO | $44 | 61% | $50 | 55% |

| Richest HMO | $39 | 35% | $65 | 49% |

| Richest PPO | $44 | 54% | $76 | 21% |

| Coverage First | $13 | 6% | $13 | 21% |

Humana actuaries examined risk selection in SmartSuite and found that Coverage First enrollees were similar in age to those in the traditional HMO and PPO plans, but higher-earning workers are more likely to enroll in Coverage First. Actuaries and other professions who make financial and risk decisions as part of their jobs were most likely to enroll in Coverage First. Most significantly, for the year prior to enrollment, employees who enrolled in Coverage First incurred claims expenses at 50 percent the overall level for Humana employees. In total, Coverage First enjoyed substantial favorable selection. However, Coverage First did experience a 30 percent decline in medical claims expenses relative to previous year claims, despite the fact that members in the previous year incurred claims expenses only 50 percent of the average for Humana employees based in Louisville. Only 31 percent of Coverage First members exceeded the $500 spending account threshold, and only 8 percent exceeded the plan deductibles. Humana actuaries report that there was no substantial rush at the end of the plan year by members to spend remaining balances in spending accounts.

Assessment

Humana's SmartSuite product provided multiple incentives for employees to reduce health care spending. Humana offered up-to-date Internet tools to track spending and provide information on medical decisions and providers. Through a defined contribution formula where the employer contribution was set below the premium of the lowest-cost plan, financial risk was transferred to employees. Cost sharing was increased in the form of hospital copayments and increased deductibles. The firm offered an HRA-like product that imposed cost sharing when using the spending account. With employees bearing greater financial risk for their plans and at the point of service, employees migrated to lower-cost plans and reduced their use of services. Savings appear substantial, largely through the reduced use of hospital services. It is possible that cost sharing within the spending account prevented an end-of-year run on the use-or-lose spending account.

While savings appear substantial, the HRA-like plan enjoyed substantial favorable selection. Medical expenses for Coverage First members were 50 percent of the group average the year prior to enrollment. Humana attempted to use modified risk selection to mitigate selection bias, but nonetheless the plan attracted a disproportionate share of low-cost employees. In general, like any HRA-type plan, if the dollars spent in the spending account exceed average prior year spending for HRA members, the plan is likely to cost the employer additional dollars.

Patient Choice

Background

Patient Choice evolved from a coalition of large employers in Minnesota known as the Buyers Health Care Action Group (BHCAG). Founded in 2000, Patient Choice operates the Patient Choice program, formerly known as Choice Plus, a plan offered since 1997 to the employer members of BHCAG. Patient Choice currently offers its product in Minnesota, Colorado, and Oregon, with other states to follow. At the time of our interview, Patient Choice had approximately 90,000 members nationwide, mostly in Minnesota. Its customers are comprised mostly of large firms, such as 3M and the University of Minnesota, although they also serve medium-sized firms, typically with a minimum of 200 employees. The product is generally offered as an add-on to other health plan offerings.

Patient Choice views its product as one of the first consumer-driven health plans, which they broadly define as plans where informed health care consumers have financial incentives to make choices about their providers and health plan characteristics. They believe because not all providers are comparable in terms of quality and efficiency, an employee's premium contribution structure should take these differences into account. Discipline to control costs should come from informed consumers, not from health plans.

Patient Choice develops and manages provider networks on the basis of costs and quality. Providers align themselves into networks called “care systems” that include primary care physicians, specialists, hospitals, and other health care providers and facilities. These care systems are assigned by Patient Choice to one of three cost tiers based on costs that are risk adjusted for the health status of the populations they serve. Patient Choice reimburses the care systems on a fee-for-service basis.

With Patient Choice, employers decide what kind of benefit coverage they want to offer. The benefit design is similar to any other health plan, with in- and out-of-network coverage having different levels of employee cost sharing. Firms contribute to premiums no more than what the lowest-cost care system would cost, so employees bear the financial burden of choosing more costly care systems. Employees choose the care system they want, based on cost, satisfaction ratings, and other features.

Once a year Patient Choice provides comparative data to the care systems that reveal how that network is performing compared with others. Employees also have access to data on satisfaction with the various care systems. Historically, Patient Choice has used a Consumer Assessment of Health Plans (CAHPS) type system to measure satisfaction, which includes measures such as how people rate their clinic, their doctor, and the ease of getting referrals. For 2003 open enrollment, Patient Choice will also provide employees with data on quality, such as care systems' performance on some key conditions such as diabetes management, and Leapfrog Group information.

Patient Choice was an early adopter of risk adjustment. Care systems submit their pricing preferences to Patient Choice, which combines this information with the provider network's claims experience along with the care management structure to arrive at an Ambulatory Care Group (ACG) risk-adjusted, per member, per month cost figure. The objective is to compare one population with another in an effort to negate the impact of illness burden on utilization of health care services in the various care systems. Patient Choice has found risk adjustment to be critical because measures such as age and gender are inadequate in measuring illness burden.

Beyond price, use of techniques such as care management, hospitalists, disease management processes, and internal formularies are essential in predicting total risk-adjusted costs, and subsequent assignment to one of three tiers. Experience has found that the actual costs of the tier groups are usually consistent with expectations based on which cost tier they are in, which suggests the risk adjustment is working.

Experience

Patient Choice reports that total cost and illness burdens (ACG scores) vary substantially across care systems, with the range between the highest- and lowest-care system exceeding 50 percent. From year-to-year, care systems that attract sicker patients tend to keep doing so, while those that attract healthier patients continue doing so. Without risk-adjustment, the wrong care systems would be rewarded. For example, in 2003, 8 of the 19 care systems would have been misclassified without risk adjustment. In 1 of these 8 misclassified cases, the error would have placed a highly efficient care system in a high-cost category; in another case, a highly inefficient care system would have been classified as low-cost, if there had been no risk adjustment. Thus, risk rating is important to ward against inefficient care systems.

Employees have demonstrated their sensitivity to monthly contributions by moving from higher- to lower-cost care systems. Patient Choice believes that “switchers” are probably healthier than average, and hence place less value on provider relationships. When care systems are moved to higher cost tiers, these care systems lose enrollment. When care systems move to a lower-cost care system, they gain market share. For example, all five of the care systems that were reclassified down to a low-cost care system gained market share in 2003. All three care systems reclassified into higher-cost tiers in 2003 lost market share. Among care systems whose classification remained the same, three gained market share, and four lost market share.

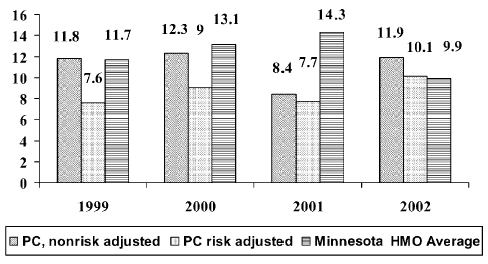

Premiums have risen slightly more at Patient Choice than the overall average for Minnesota HMO plans (60.7 percent versus 58.7 percent) over the four years of operation (Figure 1). However, Patient Choice believes that its changing mix of client firms has resulted in a sicker patient population. If one adjusts premiums for the increased illness burden of its employee population, premium increases at Patient Choice are substantially less than the Minnesota average for HMOs (39.1 percent versus 58.7 percent). What is missing from such comparisons is an adjustment for changes in illness burdens for HMOs in Minnesota over the study period.

Figure 1.

Annual Growth in Premiums, Patient Choice versus Minnesota HMO Average

Assessment

Patient Choice offers a few lessons for CDHC. The first is the importance of risk rating competing provider networks. Without risk rating, inefficient provider organizations will be rewarded for their perceived efficiency, and efficient organizations will be penalized for their perceived inefficiency. Second, Patient Choice demonstrates that with the right incentives, employee will migrate from higher- to lower-cost care systems. However, work by Harris and colleagues (2002) suggests that there is less price sensitivity when selecting care systems than when selecting competing health plans. The logic here is that switching care systems involves switching providers, and patients are more attached to their physicians than to their health plans. Third, the Patient Choice experience raises the question whether market risk can discipline physicians and care systems when the health plan represents just 15 percent of their business. If one accepts that Patient Choice is serving a population whose illness burden is growing, and that the plan is experiencing adverse selection, then Patient Choice has been very successful in its ability to contain costs. If one does not accept that the trend in illness burden has been worse than that experienced by other HMOs in Minnesota, then Patient Choice's record controlling health care premiums is little different from the other HMOs in the state.

Conclusion

Several key points emerge from our case studies. The experience of Woodward and Humana indicated that favorable selection tends to result when a CDHC plan is introduced alongside traditional PPO and HMO plan offerings. Both Woodward and Humana, for example, reported strong favorable selection with CDHC plan members incurring claims expenses roughly 50 percent of the overall average for the year prior to the introduction of the CDHC plans. This is not a surprising result because early adopters of new health insurance products are not likely to be those seeking treatment for current acute or chronic conditions or those expecting future treatment. Within the context of a large company, if all plans are self-insured and the employer risk adjusts premiums for competing plans, the company can potentially combat selection bias by altering premium sharing or by eliminating plans entirely. Thus, unless employers carefully make efforts to anticipate the risk status of enrollees to health insurance options, risk segmentation will likely occur. For convenience, we include a summary of the employer characteristics and experiences in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of Employer CDHC Plan Offerings

| Countrywide | Woodward | Humana | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly employee-only premium contribution | $88 | $8 | $13 |

| Percent enrollment, first year | 2% | 12% | 6% |

| Percent enrollment, second year | 4% | 25% | 21% |

| Demographics of enrollees | • More men | Reported to be “similar” to nonenrollees | • Age similar |

| • Older | • Higher income | ||

| • Higher income | |||

| • More family coverage |

The Definity-style HRA model places the consumer at risk for making costly health care decisions but does not directly create incentives for providers to become more efficient or improve quality: providers are typically paid discounted FFS. However, when providers are placed at risk in addition to patients, selection concerns are even more pressing, as was demonstrated in the case of Patient Choice. Hence risk adjustment was found to be a critical tool that allowed Patient Choice to sort care systems so as not to punish systems that have a greater proportion of sick enrollees and reward systems that do not have the sick enrollees but were nonetheless costly providers. The current lack of engagement of the provider in the now dominant form of CDHC—the HRA—may entail that HRAs represent only a partial step toward the market-based discipline that CDHC proponents envision in the health care sector.

These concerns aside, the Humana and Patient Choice experiences did call attention to the potential of CDHC to reduce the rate of increase in health care expenses. Humana's SmartSuite, which encompassed elements of HRAs, higher cost sharing, tiered networks, and a defined contribution formula, experienced a substantially lower rate of increase in claims expense than other Humana clients in the Louisville area. Patient Choice had distinctly lower risk-adjusted increases in premiums over the study period than other HMOs in Minnesota.

Our case studies also indicate that the more mundane aspects of health care benefits are still crucial under CDHC. Both the Countrywide and Woodward experiences highlight the importance of provider networks. For Countrywide, Definity's product offered a means of accessing a larger provider network for employees. For Woodward, enrollment in Definity's product was hampered by the inability to contract with a sufficient number of providers in the area. The issue of inadequate provider networks is important and could hold back the initial growth and acceptance of CDHC plans. It may also signal a potential advantage that traditional managed care organizations such as Humana might have in relation to upstart CDHC companies: their years of experience contracting with providers. Similarly, the role of premium contributions in the benefit design looms as large as always. Countrywide may not have experienced the same favorable selection in its HRA plan as others because employees faced lower monthly contributions if they chose the traditional HMO. Humana's effort to actuarially predict the appropriate premium-sharing arrangement indicates one approach to this issue. Also, companies highlighted the importance of educating employees about new CDHC products. Employees who understood the product were more likely to enroll. Web-based information tools are frequently mentioned as a critical dimension of CDHC, but our site visits revealed that use of the web was generally limited to checking account balances and billing issues. The role of the web is one area that merits watching, but for now it does not appear to be a major draw for consumers. Finally, Woodward's experience when rolling out its total replacement Definity product is a cautionary tale for companies planning to implement CDHC products and researchers planning to study CDHC implementations: there may be unintended and unexpected anticipatory effects once company plans are made public.

At this point there is still far more that we do not know about CDHC than we do know. Little is known about the extent to which CDHC changes enrollees' behavior, the extent to which quality of care is affected by CDHC, and whether web-based information and tools actually make patients become better consumers. Clearly, more independent research is needed on these and other questions. Ultimately, employers, by offering the product, and employees, by enrolling in the product, will decide whether CDHC is valuable, or whether it will join the ranks of health care ideas that did not pan out.

References

- Gabel J, Rice T. Understanding Consumer-Directed Health Care in California. Oakland: California Health Care Foundation; 2003. Available at http://www.chcf.org/documents/insurance/ConsumerDirectedHealthCare.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gabel J, Lo Sasso AT, Rice T. “Consumer-Choice Plans: Are They More Than Talk Now?”. Health Affairs. 2003 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w2.395. Web exclusive. Available at http://www.healthaffairs.org/WebExclusives/2201Gabel.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris K, Schultz J, Feldman R. “Measuring Consumer Perceptions of Quality Differences among Competing Health Benefit Plans”. Journal of Health Economics. 2002;21(1):1–17. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzlinger RE. Consumer-Driven Health Care: Implications for Providers, Payers, and Policy-Makers. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; Forthcoming. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuit DP. “Consumer-Driven Health Plans Drive Significant Skepticism”. 2003. [accessed on December 2, 2003]. Workforce Management. Available at http://www.workforce.com/section/02/feature/23/47/21/